Bloody fiasco

They told Private Eric West, the student from South Australia, to dump his blanket and overcoat and anything else he didn’t need. His battalion was going to storm the Hindenburg Line. It was April 9 and cold, a sharp cold that stung the nose and said snow was coming. Just up ahead, behind the heaps of spoil and the wire and pickets, lay two villages that had once sat up in a little valley but were now smoking and trembling and falling down under artillery fire. West knew the name of the village on the left well enough, but he didn’t name it in the letter he wrote to his father.

We took our capes, 24 hours rations and our rations for the morrow and, of course, any other ration we liked to take that we had. Also, our water bottles full of water. The riflemen had to carry 150 rounds of ammunition and 100 more rounds in bandoliers and two bombs. The grenadiers were issued with a bucket (that is a bag) of 15 bombs. We also had to carry our rifles and 50 rounds of ammunition … We all (I think the machine gunners included) had to carry 6 empty sand bags and a spade.

The men could return to their dugouts but they had to be ready to assemble at a moment’s notice. They were called out at 3 am on the 10th. A corporal told them they would be going over in two or three waves. West’s battalion – the 48th, part of the 4th Division – would be in the second. Once the men had broken in, the corporal said, Indian cavalry would take over. There would be no artillery barrage. West went towards the jumping-off trench. Then he saw men in front coming back and he was told to return to his dugout. ‘We learnt that the tanks that were to have been used hadn’t succeeded in coming up, or something to that effect.’

West slept most of the next day. Towards evening the men were told to make the same preparations as the night before. This time the grenadiers were not issued with spades. This pleased West: his load would be lighter. In the night he heard the sound of engines and crawled out to see a tank. Three others followed at long intervals. West thought they were slightly different to the tanks he had seen on the Somme. They had no wheels at the back for steering. To turn the crew simply stopped the track on one side.

At 3 am the men were called out again. They were told German reinforcements had been seen moving up. The Germans had been warned by what had happened the previous night. ‘Two tanks were to patrol the trenches we were to take,’ West wrote, ‘and two were to roll down the barbed wire. There were to be 12 tanks used in all.’

The men waited. Snow lay on the ground. ‘At first we just knelt down, but as the fire became hotter, we gradually got down in a prone position and lay flat in spite of the cold. Machine-gun bullets kept whistling over our heads as we crouched lower.’

The attack began. German flares went up, red, green, all colours. West noticed they were using a new signal this time, a long stream of lights that moved upwards like a snake.

It was soon our turn to jump up and move forward. First we came to a sunken road in which was a trench. We halted here for the fraction of a minute, to get collected a bit, and then pushed on. We came to the first line trench where the 46th (I think) were and pushed on to the second. All the time men were falling right and left. A shell bursting would clear a space around the men dropping off like flies. Some would be actually blown up by the shells. Rifle fire and machine gun fire became hotter as we approached.

Then West felt ‘a huge burning pain’ in his stomach. He was in the battle that would be known as First Bullecourt.

BULLECOURT WAS THE name of the village on the left. West was on that side of the attack. Major Percy Black was on the right. Because of his rank, Black knew more about what was being asked of these men than did West. At a conference around midnight Black had said to his commanding officer: ‘Well, goodbye, colonel. I mayn’t come back, but we’ll get the Hindenburg Line.’ Earlier he had told his friend Harry Murray: ‘Harry, this will be my last fight, but I’ll have that bloody German trench before they get me.’ Black seldom swore. Murray knew he was serious.

Some time before West had felt that ‘huge burning pain’, Black had led the West Australians of the 16th Battalion through one belt of wire, taken the first German trench, and gone on towards the second, where the wire seemed intact. Many of his men fell here. German bullets sparked off the wire and pickets. Someone thought they looked like a swarm of fireflies. German flares bathed the snow in red and green lights. Black found a gap in the wire and hurried his men through. He called to his runner and told him to take a message back to battalion headquarters at the railway embankment. ‘Tell them the first objective is gained,’ he said, ‘and I am pushing on to the second.’

The miracle was that, given the way the attack came about, the Australians had come so far. It was around 5 am on April 11.

BULLECOURT CAME ABOUT, almost as an afterthought, because Haig had agreed to attack in Arras as a prelude to Robert Nivelle’s offensive. The idea was to pin down the Germans there, so that they could not be rushed south, where Robert the Evangelist was going to win the war. Haig’s 3rd Army, under General Edmund Allenby, would make the main thrust by driving from Arras towards Cambrai. To the north Henry Horne’s 1st Army would send the Canadian Corps against Vimy Ridge and protect Allenby’s left. To the south Gough’s 5th Army, of which I Anzac Corps was part, would protect Allenby’s right at Bullecourt.

The whole offensive, and it was a big one, was to help the French. Whatever may be said against Haig, he always accommodated his ally. He would have preferred to attack around Ypres, where there were two objectives of real value: the German rail junction at Roulers, and the ports of Zeebrugge and Ostend. Any offensive at Ypres needed to go in as soon as the winter mud had hardened, but Haig was stuck with Arras. Nivelle was running the war.

Haig, Allenby and Gough were all cavalrymen. Haig was indulgent of Gough and prickly towards Allenby, yet Allenby was clearly the more efficient and thoughtful soldier. He had already absorbed one of the great lessons of this war: the importance of careful preparations. Allenby was a man of contrasts. He was heavily built with a volcanic temper that earned him the nickname ‘the Bull’. The story goes that he once abused an officer while inspecting trenches.

‘Very good, sir,’ the officer replied.

‘I want none of your bloody approbation!’ Allenby shot back.

Away from the army Allenby had a gentle humour and a warm spirit. He loved children, particularly his only son Michael. He also enjoyed sketching, natural history, flowers and music. He once stood for fifteen minutes in front of a ‘really lovely carved church door’ while humming the Emperor Concerto. Allenby wept and lapsed into despair when Michael, not yet twenty, was killed on the western front in 1917.

Allenby had Haig’s sense of duty but didn’t play at intrigues. Lloyd George liked him; so did Robertson. After the Arras battle Allenby was given command of the British forces in Egypt. Lloyd George told him to capture Jerusalem ‘as a Christmas present for the British nation’. Allenby turned out to be a first-rate commander in Palestine. Some said this was because the war there was one of movement and that the Turks were less formidable than the Germans. Others said that Allenby had been liberated: from Haig and his court, its pettiness and protocols.

ALLENBY’S OFFENSIVE IN Arras began in sleet and rain on Easter Monday, April 9. Successes came early. This battle had been well planned. The British had learned much from the mistakes of the Somme. The concentration of artillery was the heaviest yet used on a British front. The gunners fired shells fitted with the ‘106’ fuse, which exploded the shell the instant it grazed a hard surface. This made wire-cutting more certain. Fire-and-movement tactics were substituted for ‘parade-ground’ advances across no-man’s land. Allenby used tunnels to feed troops directly into the frontline without exposing them to artillery. Tanks were sent out to take two strong points. And the Canadian Corps, already a splendid fighting force, stormed Vimy Ridge on the first day, its four divisions attacking in line. The ridge runs north to south for about seven miles, just north of the town of Arras. The Germans had taken it in September, 1914, and the French had tried repeatedly to take it back the following year, running up 150,000 casualties. The Canadians took it in a day with around 10,000 casualties and terrified the Germans with their ferocity. The battle went well elsewhere. Allenby’s troops took 6000 prisoners and, on one front, plunged three-and-a-half miles into the German line, the deepest advance in a single day since trench warfare began.

But over the next two days the offensive lost momentum. Communications broke down as troops pushed far ahead of their divisional headquarters. The generals should have moved their headquarters forward but they were too used to the ways of trench warfare, where everything was always in the same place because the front was always in the same place. The Germans counter-attacked strongly and the battle came to be about ‘bite and hold’. Cambrai seemed a long way away.

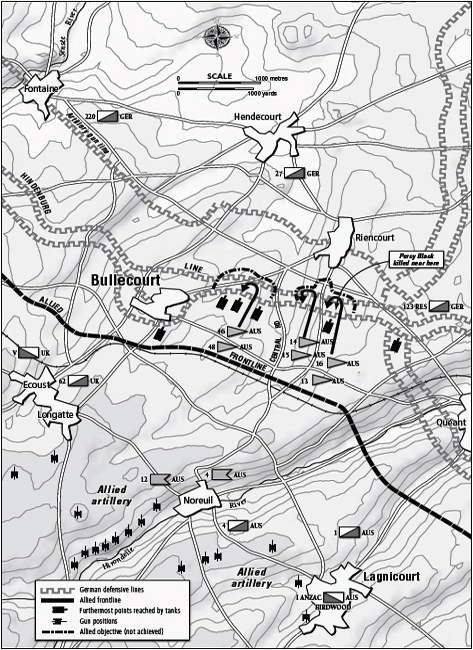

GOUGH STILL THOUGHT like a cavalryman. He looked back to the Duke of Wellington and didn’t want to see Hiram Maxim and his chattering gun. His idea for Bullecourt had Australian and British infantrymen taking the village, as well as Riencourt and Hendecourt. He would then send Indian cavalry through to join up with Allenby’s horse soldiers, who were supposed to be trotting down the Cambrai road, about three-and-a-half miles from Bullecourt.

Gough issued plans for the Bullecourt attack on April 5. Three days later General White, the chief-of-staff of I Anzac Corps, told him it would take eight days to cut the wire in front of the village. Gough simply didn’t have enough artillery to do the job any faster. Next day Gough heard of the successes of Allenby and Horne on the first day of Arras. As the British official history (always temperate but often pointed) put it: ‘It was galling [for Gough] to find himself helpless to aid in exploiting the great victory which appeared to be in prospect.’

Then, that afternoon, a tank battalion commander, Lieutenant-Colonel J. Hardress Lloyd, came to Gough with a scheme one of his officers had thought up. Gough had twelve tanks in his 5th Army. They were four miles behind the front and under the command of Major W. H. L. Watson.

Watson had worked out the scheme the night before. Like many tank men, he thought the new weapons had been misused. He felt they should be massed in front of the advancing infantry, not used in ones and twos. This was his idea for Bullecourt: a ‘surprise concentration’ of tanks massed in front of the infantry. The tanks would ‘steal up’ to the Hindenburg Line without a barrage and crush the wire. As they entered the line the barrage would come down on German positions further back. Under cover of this and the tanks, the infantry would ‘sweep through’. Lloyd bought Watson’s idea without demur, which is how the two now came to be explaining it to Gough.

‘We want to break the Hindenburg Line with tanks, general,’ Lloyd said. He briefly outlined Watson’s scheme.

Gough embraced it as eagerly as Lloyd had. It didn’t seem to bother him that he would be sending troops out without a barrage. He would attack at dawn the next morning, the 10th. He asked Watson when his tanks would need to move.

Watson was surprised. It had happened too fast. ‘There were so many preparations to be made; but I replied my tanks should move at once … we drove at breakneck speed to the Château near, which was occupied by the Australian Corps, and were left by General Gough to work out the details with the Brigadier-General of the General Staff (General White).’

It was happening too fast. ‘With two exceptions,’ Watson wrote, ‘my officers had neither experience nor skill.’ When his tanks had been unloaded from a train near Bapaume the novice drivers had twice came close to flattening a railway building. Neither Lloyd nor Watson would be in the tanks attacking the Hindenburg Line. They were architects, not bricklayers.

Birdwood and White were sceptical, and not just because the Australians had never worked with tanks before. It all seemed too extemporary. And they were supposed to have orders written and men in position by dawn next day. Gough told them the tanks would smash the wire. Only then would the infantry be asked to advance. And, said Gough, there would be no attack unless Allenby’s offensive was going so well that cavalry could pass through the Bullecourt front and begin chasing the Germans towards Cambrai.

White warmed to Lloyd and Watson. ‘They were extraordinarily keen and gallant,’ White told Bean that evening. They had said: ‘Oh! We’ll do that for you.’ They were willing to take their tanks anywhere, White said, which was amusing because these two wouldn’t actually be in them.

Birdwood remained doubtful. Anyway the first thing to do, he and White decided, was to send out patrols to see whether the Hindenburg Line was still occupied. Gough, on skimpy evidence, had suggested that it might not be.

Colonel Lloyd raced back to his headquarters to write orders for his tank company. These reached the tank crews at 6.30 pm and an hour-and-a-half later the tanks began to lurch towards the front amid sleet and snow.

Australian officers were also frantically writing orders for the 5700 infantrymen involved. General Holmes found out at 4 pm that his 4th Division was attacking Bullecourt with tanks at dawn. Troops had to be hurriedly brought forward from Noreuil and Favreuil. The 4th and 12th brigades would be making the attack, the 4th on the right, and the 12th on the left. On the Australians’ left would be the British 62nd Division, commanded by Major-General Walter Braithwaite, who, nearly two years earlier, had been much disliked as chief-of-staff to General Sir Ian Hamilton at Gallipoli, mainly because his chief interest seemed to be military etiquette.

Patrols went out to see if the Germans were still there. Captain Bert Jacka, now an intelligence officer, did the scouting for Brand’s 4th Brigade on the right. He found the wire cut in some places and intact in others. And he found Germans everywhere: machine gunners firing from a forward sap, two parties mending breaks in the wire, a patrol sneaking across no-man’s land. Jacka and the two officers with him felt that, without strong artillery support, the attack was doomed. Brand apparently passed on their views.

At 11 pm Birdwood telephoned Gough’s chief-of-staff, Major-General Neill Malcolm.Birdwood had learned that Allenby’s offensive was not going as well as it had been earlier in the day. Birdwood wondered whether a thrust towards Bullecourt was now justified, particularly as the German wire was still so strong. Why not wait for a day, when Allenby’s progress would be better known? Malcolm broke off, presumably to talk to Gough. He returned to say that Gough said the operation had to go ahead. Haig wanted it to go ahead.

White appealed to Malcolm forty-five minutes later. He said patrols had found Germans all over Bullecourt. The arrangements were hasty and the tanks an unknown. Allenby’s troops to the north had been driven back. This ‘materially changed the situation and made a haphazard attack hard to justify’, unless Gough’s headquarters knew something the Anzac Corps didn’t. Gough, through Malcolm, replied that the attack must go on. Gough said the failure of Allenby’s right increased the need for the 5th Army to do something. The reason for the assault had thus changed completely.

Late into the night, as the wind howled and flurries of snow swept the jump-off positions, instructions were still being rushed to the infantry. The artillery would fire normally until 4.30 am, when the tanks would be lined up in front of the infantry. The artillery would then switch its fire to the flanks. The tanks would go forward and take the Hindenburg Line. The sound of them would be drowned out by Australian machine-gun fire. On reaching the German line they would display a green disc. This would be the signal for the infantry to come on across the open country.

Jacka went out again to lay tapes along the start line. He was almost finished when he saw two figures approaching from the German lines. If they saw the tapes and managed to return to their lines, all surprise would be lost. Jacka worked his way behind the Germans as they came close to the tapes.

‘Halt!’ Jacka shouted. The two Germans stopped but did not raise their hands. One carried a cane. He was obviously an officer. The other carried a rifle. They were five yards away. Jacka aimed his revolver. The hammer merely clicked. Either the chamber was empty or the round faulty. Jacka grabbed the officer, who dropped his cane. The other man dropped his rifle. Jacka began to herd them towards the Australian line. According to Sergeant Ted Rule, who was back in the Australian line, the German officer ‘started to squeal and kick up a fuss’. Jacka hit him over the head with his revolver. Rule said ‘the fellow calmed down and the pair of them were taken to our C.O. Here the Hun officer complained very bitterly of his treatment, but, when our colonel told him he was bloody lucky to be alive, he shut up.’ Had the German lieutenant known the name and slightly violent record of his captor, he might have thought himself blessed.

By 4.15 am the infantrymen were lying out, waiting for the tanks. Not a sound. No tanks. The time for the attack was put back thirty minutes to 5 am. Dawn was close. When light came the Germans would see the khaki-clad figures lying in the snow. It turned out that the tanks hadn’t even reached Noreuil. Major Watson was at 4th Division headquarters. The tanks had been held up by the snowstorm, he explained. They weren’t lost, just going very slowly. The crews were exhausted. They would take another hour-and-a-half to reach the start point.

Holmes asked Watson if the tanks could attack in daylight. No, said Watson, the artillery would wipe them out. ‘I think there is just time to get the boys back,’ said Holmes, glancing at his watch. It was 5 am. It would be daylight in half-an-hour.

Colonel Ray Leane, the commander of the 48th Battalion, watched the men come back. ‘Cold, and fed up, officers and privates casually withdrew like a crowd leaving a football match …’ The men griped about what they began to call the ‘dummy stunt’. It confirmed what they had long known: that the staff officers back there somewhere were muddlers. It was now 5.20 am. The Germans put down a barrage on the line of the ridge. Most of the Australians escaped it, but over on the left, in the 48th Battalion’s sector, twenty-one were killed and wounded. Among the dead was Major Ben Leane, brother of the battalion commander. Ray searched among the dead for Ben, carried his body in and erected a rough cross over a grave that he dug himself.

Birdwood was delighted when the attack was called off. The British official history called the events of April 10 a ‘fiasco’.

ONE HAS TO see the ground at Bullecourt to realise what was being asked of these men on that freezing morning in 1917. If you stand a few hundred yards east of Bullecourt, where the Hindenburg Line stood, you see a line of trees to the south, about 600 yards away, across a plain that rises so softly that a tractor driver would barely notice he was climbing. Beyond the trees the spire of Noreuil pricks the pale blue sky. Those trees, near an old railway line, were the Australian start lines. There is nothing now, nor was there in 1917, in the way of cover between them and where you are standing.

The men making that long dash were to be completely exposed to German fire, and it didn’t matter too much that they were to start before dawn. Such an attack could only be justified if the German defences had been obliterated by artillery. This would have been difficult if Gough had possessed sufficient artillery, which he didn’t. The prospect becomes worse as you mentally sketch in the rest of the German line.

The Australians were to attack into a re-entrant (an indentation in the German lines, the opposite of a salient) between Bullecourt and the village of Quéant, out of sight behind a low hill to the east. They would be running into a cul-de-sac. They would face machine-gun fire from the front, the right and the left.

But there was to be no barrage on the German frontline because Gough had clutched at the tank plan. The Australians at Bullecourt had never worked with tanks. The infantrymen and the tank crews needed to talk to each other, to find out what each could do. (Even today infantry and tank men are expected to ‘marry up’ before an attack.) The Australians would only see the tanks a few minutes before the attack began. There would be no chance to talk to the crews.

One senses that frontline soldiers knew the scheme was rotten with flaws. They fought battles on the ground; Gough, Birdwood and White fought them on maps and, when the line wasn’t cut, telephones. One also senses that staff officers knew they should not have been cobbling up orders in such haste; they certainly knew the reason for the attack had changed. And one senses that Gough was determined to put himself and his army into the Arras battle, even if it meant clutching at half-thought-out schemes.

The attack had already been cancelled because the tank men had made appointments their machines could not keep. This should have been another warning. The British official historian had it right: it had been a fiasco. But a fiasco was better than a bloodbath and everyone had been given a reprieve. Birdwood could now argue that his doubts about the tanks had been justified. Gough could think more carefully about what he was doing.

At noon on the 10th the Australians slept in their dugouts or sat about cursing the ‘heads’. The tank men threw tarpaulins over their machines. And Gough announced that the attack would go in around dawn on the following day. The plan would be the same.

GOUGH HAD THE instincts of a huntsman: squeeze the horse with the spurs, give him the reins and hope he clears the fence; don’t think too much about what you are doing, lest you lose your nerve. Gough told the noon conference at his headquarters that Allenby would renew his attempt to break through the next day. Bullecourt would be attacked at 4.30 am on the 11th.

Birdwood and White argued against the plan. We don’t know how vigorously. Birdwood said the non-arrival of the tanks the previous morning showed the risk of relying on them. He also said that, should they arrive on time, they still had to line up correctly. If they didn’t, they would lead the infantry astray. Gough and the tank commander said they were sure at least three-quarters of the tanks would make it to the Hindenburg Line. Birdwood and White were unconvinced and kept raising doubts. Gough seemed to be losing his poise. Then he was called to the telephone. When he returned his tone was decisive again. He had been talking to Launcelot Kiggell, Haig’s chief-of-staff. Kiggell had given him a directive from Haig: the attack must be made; it was very important; Haig set great store by it. Birdwood felt he could argue no more.

White felt Gough had been speaking to Kiggell but doubted whether the dispute had been referred to Haig. Long afterwards White said to Bean: ‘I don’t think I should have given way even then. I should have let him [Gough] send me back to England first – and I don’t think we would have gone on with it.’ Other ideas had begun to form in White’s mind. Never again, he thought, should an Australian force be placed under external command unless the Australian commander had the right to appeal directly to the commander-in-chief, and also to the Australian Government.

The incident again drew attention to the curious position of Birdwood. He had affection for his Australians but he was also a serving British officer, and ambitious. He was formally accountable to Haig and Robertson and their political masters in London. And he was also, since 1915, administrative head of the AIF, which meant he was the representative of the Hughes Government in Melbourne. If there was a dispute, how did he reconcile these duties?

MINOR CHANGES WERE made to the attack plan. The infantry would go forward fifteen minutes after the tanks began their assault, regardless of the progress of the tanks. Six tanks would form up in front of each Australian brigade. The two tanks on each flank would turn outwards as they reached the German trenches. Four tanks on the left would turn towards Bullecourt village and lead the Australians in. Then six tanks would lead the British 62nd Division into Hendecourt. Finally four tanks would lead the Australians into Riencourt. Here was optimism of a high order. The previous day these tanks couldn’t reach the start line. Now they were not only going to reach the German trenches but also wheel left and right with the lightness of horse cavalry.

There would be no creeping barrage to protect the infantry in the re-entrant. The routine shelling of Bullecourt would cease at 4.45 am, just as the tanks arrived at the Hindenburg Line. Infantry orders again went out in haste. Conferences were still going on at midnight. Troops in the reserve battalions tramped up in mud and snow from near Bapaume. Private Wilfred Gallwey, a new recruit, said that he became so tired during this march that he held his rifle by the sling and let the butt trail in the mud. ‘Of what use would I be to fight tonight?’

SO HERE WERE the Australians out lying in the snow again, waiting for the tanks. The sound of the tanks’ petrol engines was supposed to be drowned out by machine-gun fire, but scouts in front of the jump-off positions could hear the engines clearly. Jacka at 3.20 am guided the first tank to arrive to a position in front of the 4th Brigade. He asked the tank officer whether it could reach the Hindenburg Line in fifteen minutes, as the orders said. Impossible, said the lieutenant.

Jacka realised the infantry would reach the wire before the tanks arrived to break it down. He told two of the battalion commanders what the tank officer had told him. The battalion commanders telephoned to divisional headquarters, asking whether the tanks could go fifteen minutes earlier. No, they were told, it was too late to change the orders.

Two more tanks arrived and were lined up. A report came in that a fourth had broken down. The final two tanks for the 4th Brigade’s front had almost reached the starting point. One became stuck in a bank; the other’s engine broke down. One briefly opened fire on the Australians in the jump-off trenches.

At 4.30 am, zero hour, only three of the six tanks were in position. And the Germans had heard them. Shells were bursting around the tanks. At 4.30 the three tanks headed for the Hindenburg Line. Green flares soared up from the German trenches.

To the left, on the 12th Brigade’s front, no tanks had arrived. By the time the infantry was supposed to go, one had turned up. The 46th and 48th battalions lay on the snow under a German barrage and waited. They could hear the tanks somewhere behind them. The first tank to arrive had opened fire on the 46th Battalion. The men yelled and cursed. A hatch opened. An officer’s head appeared, and it spoke. What troops were these? He was told – rather roughly, one assumes – that they were Australians, and on the same side, actually. The officer alighted and apologised, then asked directions to where the Germans were. His tank now lumbered towards Bullecourt but appeared to be veering too far to the right. Shortly after one of the crew returned. A shell had hit the tank. The man believed he was the only survivor.

A second tank arrived at 5 am, when the first smudges of dawn were lighting the sky and the men could see about fifty yards. It broke down in front of the jumping-off position. Fire was now coming in on the two battalions from Bullecourt village on the left. The barrage had lifted off there. Every minute brought more light. The company commanders out in the snow asked battalion headquarters the obvious question: what should they do? Go, they were told. It was 5.15 am, half-an-hour after the 4th Brigade had gone. Private Eric West of the 48th Battalion headed for the Hindenburg Line.

WEST MADE THE first line of German trenches, which had been taken by the 46th, and was going for the second when the shell fragment hit him. It was a burning pain because the metal was hot. When West fell he realised that his left arm was stiff and numb. He had been hit there too. He found a shell hole and lay on his back. A passing Australian pulled out West’s field dressing and roughly bandaged him. West kept sipping away at his water bottle. Trench mortars or rifle grenades were dropping in front of him, spraying him with earth. He held his helmet in front of his face.

He lay there for an hour, then an Australian helped him into a sap that connected the first German line to the second. ‘I was then told I should not drink any water and remembered it was dangerous to drink water with an abdominal wound, and also that I had already drunk half a bottle full. Someone discovered there were two holes in my abdomen, so put another bandage there.’

The shells kept falling. After a while the Australians realised they were being bombarded by their own artillery. Runners were sent back. ‘The second came back and said the 46th had suffered heavily and were retreating, and the Germans were in their first line again and had cut us off.’

West thought he would be left behind. He got up and tried to walk. ‘I was very stiff at first, but managed after a while.’ He blundered along the sap, which was littered with dead. West and those around him decided all they could do was jump out and run for their lives.

‘After getting about a chain, I was shot through the thigh … Our first line was along a railway embankment. By the time I reached it, I could hardly drag one foot after the other. I made my way to the dressing station and had my thigh bandaged.’ Stretcher-bearers took West to another dressing station. ‘Here our Doctor looked at my wounds and gave me my ticket and I was left outside for some time on a stretcher.’ It began to snow.

PERCY BLACK WAS almost hit by a bus at Piccadilly Circus while on leave in London. When he reached the kerb he said he’d be glad to get back to France. ‘A man’s not safe here.’ That was the style of his humour: dry and gentle. When a barrage was falling he would walk along the line, look down at a private cowering in a shell hole and say: ‘Got a match, lad?’ He inspired, but without bluster. He was a hard man: he probably had to be to survive on the West Australian goldfields. Harry Murray remembers Black fighting a well-known boxer there. Black was badly mauled early but the fight ended with Black’s friends pulling him off the boxer to save the pug’s life. Black was about the next day; the boxer was a month in hospital. Yet, Murray said, Black was ‘as gentle as a Sister of Mercy’. His every instinct was that of a gentleman. His sense of justice was so strong he could see the other fellow’s side before his own. ‘Percy never went berserk and never sought death,’ Murray said. Black ‘had all the natural fear of the Unknown’; he just didn’t let it show. He talked quietly, even in the worst of times.

Now he led the 16th Battalion out before dawn at Bullecourt. Behind him the 13th Battalion, in which Murray was a company commander, followed in support. Black had close to 700 yards to cover before he reached the German wire. He had gone about halfway when he came upon two tanks, both stopped. German flares, red, green and white, soared and fizzed over the snow. A German battery near Bullecourt village fired into the Australians from the left; another near Quéant hit them from the right. Machine-gun and rifle fire poured in from the front. Sparks flew off the wire and drummed on the tanks. Here was the madness of attacking into a re-entrant without artillery support. The tanks were supposed to have crushed the wire; in fact the infantry was ahead of them. The only thing the men could do was to try to struggle through the barbs while being shot at from three sides. ‘Come on, boys,’ Black shouted, ‘bugger the tanks.’

Murray was 300 yards behind him. He yelled to his men to lie down as machine-gun fire swept over them. He saw the 16th being ‘cut to pieces’ in the wire.

Murray reached the wire. Dead and wounded from Black’s battalion lay everywhere. Murray lost about thirty men to a German machine gun. ‘How we got through the remaining wire, I don’t know,’ he wrote afterwards. ‘A rifle bullet grazed the back of my neck, dropping me for a second. I was done! No, only a false alarm. Up again. The entanglement was just too high to straddle and so crossed and intertwisted that it formed an 8 ft mesh netting of barbed wire on which the enemy fire, converging from all points, sang a ceaseless death song.’

Lance-Corporal Bert Knowles was near Murray. ‘Anywhere, where men were grouped together trying to penetrate the barbed wire, the machine-guns simply wiped out 50 per cent with a swish; but men lay on their sides and hacked at the wire with their bayonets. Some few had cutters; others tried to cross the top, leaping from one strand to another. Many slipped and became hopelessly entangled in the loosely bunched wire. Many were shot down halfway through, and hung up on the wire in various attitudes.’

Murray reached the first trench and its nests of dugouts and shafts. Black and the 16th had already taken it and headed for the second line, 170 yards ahead. Black had ordered sixty prisoners sent back. Forty-two made it; the rest were shot down by German fire.

Black found the wire uncut in front of the second line. Eventually he found an opening, pushed his men through and told his runner to take a message back. As he finished speaking he threw up his hands and dropped. Dead. Shot through the head.

There was no time to care. Death was everywhere here. When Murray came up they told him his best friend was dead. He didn’t believe it at first. Then he saw Black’s body. When news of Black’s death reached Victoria, just after Anzac Day, the flag on a little schoolhouse outside Bacchus Marsh was lowered to half-mast. Black’s body was never found. He is out there still, in the field in front of the pretty villages of Bullecourt and Riencourt, from where you can hear dogs barking and children playing.

AND THE WAR went on, though not for the tanks. They had been in this battle all right, and had the casualty figures to prove it. But they had not much influenced the course of it, apart from drawing some fire off the infantry. They had certainly not done what they were supposed to do.

Eleven tanks set out. By 10 am all were destroyed or disabled. One – designated Tank Number 799, on the 4th Brigade’s front – veered far to the right, towards the little hill that hides Quéant. The Germans peppered it with armour-piercing bullets. The tank caught fire and the commander was killed. The driver of a tank in the centre was decapitated. Most of the tanks became chambers of horrors: ricocheting bullets, flying splinters of metal, the smell of petrol and vomit and blood, noise and blindness. Of the 103 crewmen who went out, fifty-two were killed, wounded or missing.

Bean watched the battle from behind the embankment. When dawn came, he saw what looked like slugs crawling across the snow. A flash from the slug: the tank’s six-pounder. Bean noted in his diary that the light that April morning was ‘peculiar’. The snow on the ground made all objects look black. One couldn’t tell the difference between German grey and Australian khaki.

THE POOR LIGHT produced a mistake that was to rival Gough’s faith in the tanks. The Australians from both brigades had, despite frightful losses, fought their way to the second German line. It would have been foolish for them to have tried to go on further: there were not enough of them left. What they needed was artillery support to stop the Germans counter-attacking. Murray had effectively become the 4th Brigade leader in the frontline. At 7.20 am he first called for a barrage. Seventeen times his men fired the SOS signal: a green flare, followed by a red then another green. Not a shell came to help them.

There was a reason. At 5.35 am an Australian artillery observer reported seeing tanks in Bullecourt and Riencourt. Shortly after an observer said he could see Australian infantry in the two villages. The observers reported ‘Bullecourt ours’. Now they could see Australians beyond both villages. Then they could see tanks moving on Hendecourt, which would have put them a mile inside the Hindenburg Line. All the reports were wrong.

Gough was delighted when they reached him at 7 am. It was time to bring up the cavalry. He ordered the 17th Lancers, Haig’s old regiment, forward. Gough was going to do what he and Haig had wanted to do since the war began: pass cavalry through a gap. Except there was no gap.

MURRAY SENT A message back at 7.15 am. It arrived at 8.45. Murray reported that his brigade held the first objective and part of the second. The tanks were out of the fight. It was impossible to go further. He needed as many rifles, hand grenades, ammunition and white flares as could be sent. Major Black was dead. ‘With artillery support we can keep the position till the cows come home.’

Before Murray’s message arrived Bert Jacka had been prowling the back area of the battlefield. At 7.21 am he told General Brand, the commander of the 4th Brigade, that the tanks had failed completely: they weren’t where the artillery observers were saying they were; they had never been there. Bean, who was nearby, wrote that the tanks could be seen motionless, and in most cases burning, all over the battlefield. The Australians here now knew the truth: they had to give their two brigades artillery support.

THE POSITION IN the frontline at this time was something like this. The four battalions of the 4th Brigade were in the two German trenches, but between one-quarter and one-third of them had already been killed or wounded, mostly around the first belt of wire. The men from all battalions looked to Murray for leadership: he was the best-known officer left. Several officers asked him if they should try to go on to Riencourt. No, said, Murray. They had no tanks to support them, their casualties were already high and they were short of ammunition. They had to fortify. They had to hang on.

The 12th Brigade was to their left. The two brigades had not quite linked up; there was a gap in the middle of the battlefield. There were also gaps between the front and rear battalions on the left. Only two battalions of the 12th Brigade had gone out: the 46th and the 48th. The 4th Brigade had been hit by fire from Quéant, to its right, the 12th by flanking fire from Bullecourt village, to its left. The 46th Battalion had reached the wire without help from tanks or artillery and taken the first trench. The 48th passed through them and went on for the second trench.

Lance-Corporal George Mitchell was a Lewis gunner in the 48th. He saw showers of sparks flying off the German wire, forty yards ahead. ‘The ground was a carpet of dead and dying. On the wire were still forms, and others that squirmed violently.’ Mitchell said he got the ‘wind up’ and thought of dropping into a shell hole. Then, he said, he thought of the strength and courage of his mates and went on.

Mitchell and the men from the 12th Brigade found the wire in front of the second trench mostly uncut. This is where Eric West was wounded. A South Australian farm hand said afterwards: ‘We were being raked by machine-gun fire and shelled with shrapnel. Wounded and dead men were hanging in the wires all around me, and I noticed that the shell-holes were full of wounded.’

By the time the 48th Battalion took the second trench Allan Leane, nephew of Ray, was the only company commander left. He ordered his men to bomb to the right, towards the 4th Brigade. The 48th also tried to force its way to the left, towards Bullecourt village, but was held up by fire from a sunken road that radiated from a junction of six roads and tracks just in front of Riencourt. Back in the first German trench the 46th Battalion could make no progress to the right but extended its line to the left. Captain Frederick Boddington, a Queensland architect, is said to have himself killed eleven Germans as he pushed to the left and came close to the edge of Bullecourt village. Not long after Boddington was killed.

At 7 am the 4th and 12th brigades held an awkward and narrow front that was not joined up. They could hang on, tired and depleted as they were, if their artillery would only throw down a protective barrage just beyond the second trench. The brigadiers back at the railway embankment knew this well enough. But the generals further back again were still inclined to believe the reports that their men had gone on to Bullecourt and Riencourt.

THE HOLDING ON began. Murray remembered an incident that occurred about 9 am. A small party in his battalion had been assigned to fill in the German trench so that cavalry could cross. Only one member of this party survived to reach the trench. Men now came to Murray to complain that a man was filling in the trench and thus stopping them from getting along it. Murray found a youngster, working with pick and shovel, up on the parapet, completely exposed.

‘What are you doing, lad?’ Murray demanded.

The youngster stopped work, straightened himself up and told Murray he had orders from his colonel to fill in the trench.

‘Get down at once,’ Murray said. ‘Don’t fill that trench. We want it and you’ll be killed if you stay there.’

The youngster grinned. He was uncertain. Should he obey the pre-attack orders or this captain with the neat little moustache? He decided to obey the captain.

Then Murray heard the ‘sickeningly familiar thud’ of a Mauser bullet hitting flesh and bone. ‘He sounded a long shuddering “Ah-h-h”,’ Murray wrote nineteen years later, ‘and toppled over, never speaking again.’

THE GERMANS MUST have wondered why they weren’t being hit by artillery. They counter-attacked the 46th Battalion, the rear of the Australian left, after 7 am from Bullecourt village with bombs and a trench mortar. They also bombed the 46th from the gap between the two Australian brigades. The Australians were running out of bombs and ammunition. The 47th Battalion was drawn into the fight to carry up bombs. Around 9.30 Allan Leane counted his men in the front trench. There were about 227 of them holding a 600-yard front. About 750 had set out just over four hours ago. In the back trench, the 46th, even though it now included reinforcements from the 47th, was down to a little more than 100 men. There was now no way these men could join up with the 4th Brigade.

First Bullecourt, as this battle would be known, was like Lone Pine. The fighting was mostly with bombs and, occasionally, bayonets. As on the first day at Lone Pine, there was no continuous front but dozens of separate fights, many of them over stops hastily built into trenches. The Germans were in front of the Australians in the forward trench and also behind them. They were between the two Australian brigades. And they were still pouring in fire from the flanks of the re-entrant. First Bullecourt was about anarchy.

The 4th Brigade also fought off a series of counter-attacks. Wounded could not be got out. The Germans were still sweeping the plain between the front and the railway embankment with machine-gun fire. Two captured German medical orderlies tended the serious cases in the frontline. Thirty German prisoners were sent back towards the embankment, only to be shot down by their own side.

BY NOW BOTH brigadiers at Noreuil and the battalion commanders behind the embankment all wanted a protective barrage. The gunners refused, insisting that the infantry and tanks had gone past the Hindenburg Line and would thus be where the barrage would fall. Tempers rose. ‘A most aggravating telephonic communication took place,’ a man in Brand’s headquarters wrote. The dispute was eventually referred to Birdwood at about 9.30 am. He supported the gunners.

Gough lived with the same hope. On his orders a squadron of the 17th Lancers had galloped up to the embankment. The Germans saw them and shelled them. Then they spotted the rest of the regiment massed further back and shelled it. A few horses were killed and many more ran about, big-eyed and terrified. The cavalry pulled back, but the horse culture lived on among men like Haig and Gough. One day there would be a gap. And then war would revert to its proper form.

Science had not taken over war entirely. Just before 10 am a pigeon brought a message from the 4th Brigade troops asking for bombs and ammunition. The message was timed at 7.10. Around the same time a message came in from the 12th Brigade. Its men also needed ammunition and water for their machine guns. They could see Germans massing at Riencourt.

By 11 am, General Holmes, the commander of the 4th Division, knew what the brigadiers and colonels closer to the front knew. He sent a telegram to Anzac Corps: ‘Situation appears to be that we are in Hindenburg Line within our proper limits, but no more. Not in Bullecourt or Riencourt … Apparently no tank actually reached Hindenburg Line.’ Holmes now wanted an artillery barrage.

AN HOUR EARLIER the Germans had begun a big counter-attack from the front and the flanks. The artillery could not have shelled the Germans on the flanks, even if it had wanted to: they were too close to the Australians. Fresh bomb fights broke out.

Captain David Dunworth was twice wounded and ended up a prisoner. Afterwards he told the story of Lieutenant Henry Eibel, a Queensland farmer who was a brother-officer in the 15th Battalion. When the bombing became furious Eibel paused, turned to a man and gave him his papers.

‘Give these to Captain Dunworth and tell him I’m finished,’ Eibel said.

‘But you’re not dead,’ the man said.

‘No,’ said Eibel quietly, ‘but I will be by the time you’ve delivered these.’

Eibel returned to the fight, and died.

Murray watched his men drop in dozens. ‘Oh for that barrage!’ he wrote long afterwards. A sergeant brought a message back that there was to be no barrage. Murray likened this to a death sentence. Men turned to him and said: ‘What now?’ The fighting became more desperate. The Germans with their plentiful supply of grenades were bombing the Australians out of bay after bay. A group of Australians put up a white flag. Murray ordered it shot down, but he knew the truth. All his men could do now was try to get back to the railway embankment. He wrote afterwards that he told the men they were entitled to surrender if they wanted to. The chances of escaping were almost nil. ‘It was like expecting to run for hundreds of yards through a violent thunderstorm without being struck by any of the raindrops.’ The men set off for the embankment. An officer with a smashed arm yelled: ‘Every man for himself.’

Murray tore up copies of his code signals, trod them into the mud and started back. ‘Now we turned for the last and most hopeless fight of the day; completely surrounded as we were, it looked as if it could only end one way, but, owing to the dust, haze and smoke, some of the German machine gunners mistook their own men for fleeing Australians and opened a murderous fire upon them, completely relieving the pressure on us and thus giving us time to get over the wire.’

Bert Knowles, who was in Murray’s company, dived from shell hole to shell hole. He fell over climbing through the wire and lay still among the dead around him. Then he resumed his dash. Bullets droned past him and dug into the earth. He flopped into another shell hole. He thought he would have a spell there. ‘I do not know what time it was then, but nothing had passed my lips since about 3 am. I had not even had time for a cigarette. My mouth was full of dust, and a taste of cordite and smoke of explosives. I ached all over through heaving bombs, dragging wounded men, and bags of dirt. My clothes were in rags and thighs and arms were scratched with barbed wire.’

Murray was struggling with the wire when he felt a bullet skim across his back. It broke the skin, nothing more. And now, now that he was almost safe, he succumbed to the strain. He was exhausted and unnerved and could go only a few yards at a time. A shell whined and left a crater ahead. Murray fell into it. He put out his hand and burned it on a hot fragment from the shell. The burn ‘acted as a tonic, bucking me up a little bit’. His mind cleared.

He made the old frontline and began to trudge back towards Noreuil. All he wanted to do was sleep. His colonel gave him several nips of whisky. ‘As a rule a little spirits affects me, but that night it had no more effect than water.’ He met the quartermaster, who had brought up his horse. ‘What a feeling of relief to sit back luxuriously while my neddy stepped smartly forward. I felt I could go to sleep and leave it all to him.’

The counting began. There were only seventeen unwounded survivors in Murray’s company. The 4th Brigade had sent out four battalions and from these only nine officers had returned. No officers returned from the 15th Battalion from Queensland.

MUCH THE SAME had happened on the 12th Brigade’s front, except that the men there hung on a little longer. Private William Evans of Penshurst, in Victoria’s Western District, was cut off and taken prisoner. A German marched him along a trench where they met another German. The two lost interest in Evans. They stood on the fire-step and shot at the backs of the retreating Australians. Evans saw an Australian body at his feet. He stooped, pretending to tie a bootlace, and rummaged in the pockets of his dead comrade. He found what he was looking for: a grenade. He eased the pin out and gently placed the bomb between the feet of the two Germans, then slipped around the traverse of the trench. When the bomb exploded he jumped out and headed for the embankment.

The 48th were 150 yards ahead of the 46th. George Mitchell put down his Lewis gun, picked up a rifle and began a duel with a German bomb-thrower. He fired at him and missed. He worked the bolt to fire again. The magazine was empty. ‘So I shook my fist in sheer rage, and the Fritz grinned amiably back at me.’ Mitchell waited ten minutes or so. The German popped up again. Mitchell shot him through the head.

The 48th didn’t realise that they were surrounded. Allan Leane wrote in his message book at 11.20 am that his position was ‘as strong as it could be made’. Observers back at the embankment knew better. They could plot the German advance by the white puffs of German bombs. Then they saw men standing with their hands above their heads – Australians. Now they knew that the battle was lost. Colonel Leane called for an artillery barrage to protect the retreat. The artillerymen were now conceding that perhaps the Australians had not gone beyond the Hindenburg Line. At 11.45 am the gunners opened up on the 4th Brigade’s front. The 4th by then was streaming back towards the embankment.

The 48th Battalion was still in the second German trench. Allan Leane tried to rally his men. Then he was wounded. And then, as Eric West recounted in his letter to his father, the Australian barrage began to fall on the 48th. Now – it was about 12.25 pm – Leane decided to burn his codes and papers. An hour after the other battalions had left the 48th came out. Those who witnessed the 48th’s retreat were astonished at what they saw. Bean saw them come towards him with ‘studied nonchalance’, walking, even though the German machine guns were still chattering, picking their way through the wire, carrying Lewis guns on their shoulders, arms around the walking wounded. ‘Wherever Australians fought, that characteristic gait was noted by friend and enemy, but never did it furnish such a spectacle as here.’ Many were killed or wounded as they returned. The wounded lay on the wire. The Germans shot those who were beyond recovery. These were acts of kindness rather than brutality. The 48th’s officers came out last.

Allan Leane had recently become engaged to be married. He had written home that he felt ‘the luckiest man alive’. He didn’t come out. He was seen hopping towards the wire. He died a few weeks later in a German hospital. Ray Leane, whose tunic had been ripped off by a shell-burst, had thus lost his brother and nephew in the battle. Another of his relatives had been shot through the eye while trying to salvage a tank. The Joan of Arc battalion was no longer made of all Leanes.

George Mitchell wrote in his diary that he felt like weeping as he stepped over the wounded that had to be abandoned. ‘They looked up at us but said nothing.’ He tried to help a wounded man into a shell hole but the man shrieked with pain and he was too big to carry. Mitchell walked out alone, past blazing tanks and a wrecked aircraft. When he reached the old Australian line they told him Colonel Leane wanted to see him.

Leane had watched him walking back. ‘I saw a tall non-com calmly striding down the hill with a Lewis gun on his shoulder. I was so impressed by his cool demeanour, despite the fact that he was under heavy shell and rifle fire, that I sent for him and congratulated him for his good work in sticking to his gun.’ Leane promoted Mitchell to lieutenant. Mitchell also received the Distinguished Conduct Medal.

AN UNOFFICIAL TRUCE broke out about 2 pm. The Australian artillery was still firing when it was noticed that many of the Germans about the wire were medical orderlies. The Australians could see the white bandages they carried. The barrage was stopped. Australian parties went out. The Germans fired on the stretcher-bearers, then stopped when they saw the Red Cross flags. The Germans placed badly wounded men outside the wire where the Australians could pick them up. Snow began to fall about 6 pm. The Germans suddenly shouted: ‘Finish hospital!’ The truce was over. Neither side fired a shot during the night.

THE GERMANS HAD taken about 1170 prisoners, their biggest bag ever of Australians, and treated them well enough at the front. Once the prisoners reached Lille, however, other Germans set about punishing them. They were humiliated by being marched through the city’s streets. Then they were crowded into dungeons in a fort. For eight days they were fed one slice of bread a day and ersatz coffee. The air was fetid. The men were given no blankets and slept on a damp stone floor. They were being treated so, an official explained, because the British had been making German prisoners work within range of German guns. They would be kept hungry, he said, given no beds and worked hard under shellfire. There would be no soap or towels or boots. He kept his word. The Australians were made to work under their own artillery fire for three months.

The Germans caught Bert Knowles. He had dozed off in the shell hole. Then he heard voices he could not understand. Germans. He and other Australians were taken to a house behind the lines. An officer looked into Knowles’ diary and began yelling when he found pages torn out. Knowles understood only two of his words: ‘Englander’ and ‘swine’.

THE CASUALTY FIGURES (which include those taken prisoner) were frightful. The six-and-a-half battalions went into the fight each about 750-strong. Murray’s battalion lost 567 men, including twenty-one officers. Percy Black’s battalion lost 636. The 4th Brigade’s casualties came to 2339 of the 3000-odd troops it sent out. The 12th Brigade lost 950. Of these, 436 were in Eric West’s 48th Battalion. Total casualties were thus 3289, which, in percentage terms, puts them on the same scale as Fromelles.

The 4th Division was pulled out of the line and rested in huts on the old Somme battlefield. As he left the battlefield Ted Rule saw Brand, his brigadier, and Colonel Peck, his battalion commander, ‘sobbing like little schoolgirls’. A few days later Birdwood visited the 4th Brigade’s huts.

Rule said that Birdwood had a standard ‘bloodthirsty’ speech. This usually began: ‘Now, boys, I know you are all anxious to get back into the line and give the Huns another thrashing.’ And it usually ended: ‘Well, boys, I sincerely hope that you are all writing home to your mothers.’ Birdwood delivered the standard speech, then gathered the men around him and started to unburden himself. This was a conversation, not a speech. Rule recalled parts of it: ‘Boys, I can assure you that no-one regrets this disaster that has befallen your brigade more than I do … I can assure you that none of your own officers had anything to do with the arrangements for the stunt … We did our utmost to have the stunt put off until more suitable arrangements could be made.’ Birdwood offered not a word of criticism of his superiors, ‘but it was plain to me that he shrank from being contaminated by the bloody fiasco’.

The incident stirred Rule’s imagination. ‘Never before had I questioned the infallibility of those who held our lives in their hands … Now one recognised that, in spite of all the pomp and splendour of their rank, they were fallible flesh and blood; the same as we.’

THE HORSE AMBULANCE picked up Eric West, who we left lying in the snow with his three wounds. West said the horses were worn out. They took him some distance, then he was transferred to a motor ambulance, which was much smoother. The staff at the casualty-clearing station cut his clothes off. ‘I was glad of this as I seemed to be lying in a sort of pool of water, and my feet were well nigh frozen as they had been for pretty well the last 24 hours.’

It was now the night of April 11. They put a blanket over him and carried him into the operating theatre. They laid him on a cold table. West objected and they put something under him.

Picture one lying there; big, grim men standing around in white overalls looking at me menacingly. They paid first attention to the wound in my abdomen – started swabbing it. The pain was unbearable at the least touch. The operators put an instrument through the wound and told me I was very lucky. I could not see this. I had been cursing my luck for the last five minutes, but I did not start an argument over it. Someone then put a nosebag over me and let me inhale the beautiful fumes of chloroform and ether and I was told to count to … then …

When he awoke doctors and nurses kept telling him he was lucky. He was taken to another ward; another abdominal case was next to him. ‘He was pretty bad, was not so lucky. An R. C. Padre came in to see him. He was not there next morning. One of the motor drivers was drunk that day. I learnt afterwards he drove rather recklessly and was arrested, as two abdominal cases he had on board died before morning.’

Several days later a doctor pulled out the plug in West’s abdomen and he realised why everyone had told him he was lucky. The wounds in the abdomen were about three inches apart; each hole was about two-and-a-half inches by one-and-a-half inches; there were burn marks around the holes. But they were through-and-through wounds: the shell fragment had gone in one side and out the other. It was the same with his arm and the bullet wound to the thigh.

West recovered and took a Master of Science degree at the University of California. He became officer-in-charge of the CSIRO Division of Irrigation Research at Griffith, New South Wales. He had learned a little about irrigation in France. He told one of his sons that he was always bemused when officers ordered the men to bale water out of trenches. The scientist in him knew the floor of the trenches was below the ground water table.

THE BRITISH OFFICIAL history says of First Bullecourt: ‘In the whole course of the War few attacks were ever carried out in such disadvantageous circumstances against such defences.’

At one level, that of the men on the ground – the Blacks, Murrays, Wests, Rules and Leanes – the attack had been an epic of great-heartedness. These men had broken the Hindenburg Line without artillery support and with modest help from the tanks. They had held two lines of German trenches for hours without artillery support. They had proved they had the discipline that counted: discipline under fire, discipline in adversity. And the unwounded had walked away with a mixture of nobility and cheek. War is often romanticised, mainly by leaving things out, and the abattoir is sometimes presented as an Arthurian jousting ground. First Bullecourt was an abattoir; but it also had moments that showed the human spirit at its most sublime. It remains curious that no Victoria Crosses were awarded afterwards. Murray received a second Distinguished Service Order and was promoted to temporary major. In his unpublished Some Reminiscences Murray said Birdwood told him that he would have received a second Victoria Cross had the battle been won.

At another level – that of the higher command, the world of the Haigs, Goughs, Birdwoods, Whites and countless staff officers – the battle should have been a thing of shame, a cause of sackings and censure. It might have been excusable in early 1915, but not in 1917.

Gough deserves most of the blame for First Bullecourt. Just as Fromelles probably would not have happened without Haking and his obsession, First Bullecourt could not have occurred without Gough and his bluster. Gough simply took a gamble with the tanks, the sort of risk other army commanders, such as Allenby and Herbert Plumer, would have spurned. When the tanks failed, nothing could save the Australians. Bean, a temperate man, assailed Gough in the Australian official history, which came out in 1933. Gough had conducted an ‘experiment of extreme rashness’. He had tried with ‘boyish eagerness’ to deliver a death blow. He broke rules recognised even by platoon commanders. He attempted a deep penetration on a narrow front. He attacked into a re-entrant. He bought, on impulse, a scheme devised by an inexperienced officer of an experimental arm. After the tanks had failed on April 10 and confirmed the fears of his subordinates, he repeated the identical operation the next day. His judgement at Bullecourt was ‘the plaything of an almost childish impetuosity’.

But it is too easy, and also unfair, to blame Gough alone. Birdwood couldn’t seem to work out where his loyalties lay. He should have protested more strongly, as White should have. White was gracious enough to admit as much after the war. Birdwood glossed over First Bullecourt with two bland paragraphs in his autobiography Khaki and Gown.

And Bean glossed over the Australian mistakes at Bullecourt. No blame attaches to the brigadiers at Noreuil or the battalion commanders, who were under fire behind the railway embankment. Further back, however, the staff work was sloppy and the final plan too complicated, which in turn was one of the reasons the artillery performed so poorly. The gunners reported a series of false sightings, failed in their counter-battery work (the Germans reported that their gunners incurred only nine casualties) and, when they eventually began firing on the battlefield itself, managed to land shells among the 48th Battalion.

Communications broke down, as so often happened, shortly after the infantry went forward. For the next few hours there were at least four battles going on: the real one in the Hindenburg Line itself; the battle the brigadiers and colonels just behind the line thought was going on; the battle the artillery observers thought they were witnessing; and the one going on in Gough’s mind as he sent cavalry into a gap that didn’t exist.

A few hours after First Bullecourt ended Gough sent a message to the Australian division. He said he was ‘satisfied that the effect upon the whole situation by the Anzac attack has been of great assistance’. Only he knows what he was trying to say.

BEAN IN 1930 sent the page proofs of his Bullecourt narrative to Edmonds, the British official historian. Edmonds passed them to Gough for comment and the general reacted strangely. If he felt wronged, Gough needed to refute Bean’s criticisms with forensic certainty, point by point. Instead his response was lame and rambling. He began by telling Edmonds: ‘It is evident that the writer is animated by a strong personal dislike to myself, which causes me some pain, as I admired the Australians as soldiers and got on very well with those I met.’ He said that at Bullecourt he was inspired with a determination to beat the Germans and win the war, which one would have thought was self-evident. He then admitted the attack was on too narrow a front. He was inclined to blame himself for attacking when he did, but he was trying to help Allenby. Gough concluded by saying that communications between his army and Allenby’s were poor, and that Haig’s headquarters was probably to blame for this. Kiggell, Haig’s chief-of-staff, seldom visited the armies’ headquarters. (Here Edmonds wrote in the margin: ‘He [Kiggell] hardly ever left his office and did not visit the front until he was relieved of his post as CGS.’) Gough said too much was done on the telephone.

Before Bean sent out his proofs Edmonds had written to Bean: ‘I expect that I shall be in full accord with you over Bullecourt. I was at Gough’s HQ at the time, and I remember that my opinion of him fell lower and lower. When the news of the Australians being cut off came he was furious and shouted over and over again, “They ought to have been supported,” and began to look for scapegoats.’

Neill Malcolm, Gough’s former chief-of-staff, also saw Bean’s proofs. His response was as muted as Gough’s. Bean, he said, would have been more sympathetic had he been at Haig’s conferences. ‘The only real mistake which can be seriously charged to Gough was, I think, his over-confidence in the tanks. The event proved him wrong, but the astonishing degree of success achieved by the 4th Aust. Divn. without them surely proves how great the result would have been had the tanks not failed us …’

In a note attached to Malcolm’s comments Edmonds said the general opinion was that Gough and Malcolm were a bad combination. Gough needed a chief-of-staff who would restrain him. Both were too rash and headstrong. ‘Both now have lucrative jobs in the City while many soldiers who did better service are living in poverty. Such is life.’

A month later Edmonds sent Bean a letter from Colonel D. K. Bernard, whom Edmonds described as ‘one of the best officers in the Army’. He had been on the staff of the 4th Australian Division at Bullecourt and Edmonds had sent him Bean’s proofs. Bernard replied: ‘I read it with intense interest and it brought back vividly to my mind those tragic days of April 1917, when General Gough sent 4th Australian Division to what was really certain destruction.’

THERE IS LITTLE sign of destruction at Bullecourt today, not until you poke around. The three villages lie in strong cropping country, yellow-brown soil that, to the eye anyway, looks richer than the Somme. Wilting corn stalks sway seven-feet tall in the north wind. Big Friesians pick at the grass and stare with credulous eyes at passing cars. A crow circles overhead.

The villages belong to postcards: grey church spires, red and orange roofs, leafy glades, orchards, tomatoes blushing red in the vegetable plots, red-brick barns with lofts and old pig-sheds, dogs and ducks and cobblestones. And on all sides fields of wheat, barley, corn, sugar beet and vegetables. Driving a tractor here can still be dangerous. A farmer recently set off a phosgene-gas shell, inhaled the fumes and spent three days in hospital.

An Australian memorial, Peter Corlett’s statue of an Australian soldier, rifle slung, his back lumpy with gear, stands on the Bullecourt–Riencourt road, Rue des Australiens. French and Australian flags flap in the wind. Gum trees have been planted near the statue and are doing poorly. The soil is too rich for them. Like the men in the ground here, the gum belongs to a harsher landscape.

This is roughly where the Hindenburg Line stood. Look to the south and you see the arena where dreams died for young men and bullets sparked off barbed wire. It is an open plain with barely an undulation. At the far end is a line of trees. They mark the line of the railway embankment, the Australian start line. That’s where the colonels stood, wondering about the six-and-a-half battalions they had sent out. A spire peeps above the tree line. That’s the village of Noreuil. The Australian artillery, for all the good it did, was in a valley between Noreuil and the tree line.

You walk along the Bullecourt–Riencourt road until you come to Six Cross Roads, which was on the German side of the front, facing the spot where the 48th Battalion was trying to hang on. German machine guns here shot down the Australians from the front. Look to the left and you see the gentle hill that hides Quéant. German machine guns fired into the Australians from there. Look to the right and you see Bullecourt. The Germans were firing from there too. Stand here long enough and First Bullecourt seems like madness.

And now you walk out into the re-entrant itself, a field of wheat stubble that crackles and crunches underfoot. Puffs of yellow dust rise with each footfall and you smell the dressing of blood and bone. It is hard to imagine how it looked on that day long ago when snow lay on the ground. An Australian sergeant taken prisoner passed close to where you are standing on his way to the German rear. He said the snow was broken by thousands of patches, black and red. The black patches were bodies, the red splashes of blood. He spoke of wounded men restlessly tossing and groaning.

Now you also start to notice the signs of destruction: a nose cone from a German shell, shrapnel balls, German bullets, sharp-pointed and rusted. On the hill that hides Quéant farmers found Tank Number 799 buried under topsoil. This was the tank that veered far to the right on the 4th Brigade’s front. Pieces of the tank now lie in a farm barn. Here is a great rusting track and chain links as thick as one’s thumb. Here is the six-pounder gun poking out of its spon-son and, underneath, the rack for the shells. When you see a Mark I tank in a museum you are struck by its apparent blindness. There is no turret, nothing that says the iron creature can see. And that was the fate of 799. It blundered, like a blind and wounded animal, into the German lines, where it was surrounded, taunted, pulled down and killed.

Claude and Colette Durand, both formerly schoolteachers at Hendecourt, more than twenty years ago appealed for reminiscences from Australians who were at Bullecourt. They spread the handwritten letters on the kitchen table. A Tasmanian writes: ‘The British Tank corps let us down badly & there was no co-operation between the Tanks and infantry.’ A New South Welshman tells how he was wounded on the wire as a nineteen-year-old. When the retreat began two men grabbed an arm each and tried to drag him back. Both were killed by machine guns. Stretcher-bearers brought the man in near dusk. He thinks he may have been the last man picked up that day. They are all gone now, the Bullecourt men. We perhaps should have made more of them when they were alive.

WE RETURN TO the battlefield. A car pulls up. Two men alight.

‘Bonjour,’ we say in appalling French.

‘Gidday,’ one of them replies.

The men are Arthur and Clive West, sons of Eric West, come to look over the scene of their father’s heroics long ago.