Mutiny

Robert Nivelle was so good at courting politicians that he almost qualified as a flirt. Yet he wasn’t much of a politician himself. In selling his forthcoming offensive he had made a mistake. He had not only defined the terms by which his success should be judged; he had also defined them too narrowly. Talk of tactics and logistics tended to faze politicians. Victory, quick and neat: that was what they wanted to hear about. Nivelle had told them he knew things other generals didn’t. He predicted that he would rupture the German lines in a day. He was the alchemist; he had the formula. Nivelle had set himself up: anything short of a quick breakthrough would be failure.

Haig and Robertson were clumsy at courting politicians. They patronised them, looked down on them as a lesser species. Both were inarticulate, secretive and narrow in their interests. Yet Haig would never have made the mistake Nivelle was now making. On the Somme the previous year he had not talked too loudly about breakthrough, even though that was what he was trying for. When the opening days brought failure and confusion, Haig and his apologists began to say the battle was about wearing down the Germans, and that would be their line for posterity.

By the time Nivelle’s offensive began on April 16, five days after First Bullecourt, just about everything was against him. Prominent members of Ribot’s new government, notably Painlevé, the War Minister, doubted the scheme would work and said so, causing Nivelle to offer his resignation. Painlevé and General Philippe Pétain preferred to wait for the Americans to come into the war. Nivelle’s army commanders didn’t believe in the offensive. They knew the Germans also had a new scheme and it was called defence in depth. The Germans had thickened their position on the Chemin des Dames ridge above the River Aisne with two extra lines of trenches. The defences ran back eleven miles and the strongest part of them was at the rear. Nivelle’s plan called for the French to advance about four-and-a-half miles in eight hours. This would be a prodigious ‘rupture’ by the canons of the western front, but it would still leave the French infantrymen well short of the main German position, and exhausted too.

Nivelle had lost surprise. The Germans knew, in general terms, what was coming. Nivelle had allowed far too much loose talk. Moreover the Germans, as recounted earlier, had captured his plans with a French prisoner. The revolution had reduced the Russian army to a shambles: it could not help Nivelle with an attack in the east; it could not help itself. The Italians wanted to do something on their front but decided they couldn’t.

All Nivelle had going for him was the enthusiasm of his rank-and-file troops and his own self-belief, and even that appeared to be faltering. Perhaps he simply didn’t know how to escape from the trap he had built for himself.

THE ATTACK BEGAN at 6 am on the steep wooded ridge above the Aisne, in front of the line that ran from Soissons to Rheims, amid mist and icy rain that turned to sleet and snow. The rough weather made it hard to plot the course of the battle but some things were soon obvious. Nivelle’s whole scheme depended on massed batteries keeping the Germans underground, but the German machine guns were firing and much of the wire was uncut. The barrage ‘crept’ too quickly for the infantrymen, who, as always, went forward bravely. Many of the tanks failed to reach the start line. Senegalese troops shivered in the sleet. Their hands were so cold they had trouble fixing their bayonets and their dark-brown faces turned grey. The casualty stations could not handle the procession of wounded. Lightly wounded Frenchmen pointed to the front and said ‘C’est impossible.’ The attack slowed, then stalled. The gains were negligible. The grand scheme had failed as quickly as it was supposed to have succeeded.

Nivelle had lost contact with reality weeks or months earlier; he wasn’t going to re-embrace it now. He ordered fresh attacks. The deepest gain at the end of four days was about four miles. The French had taken about 20,000 prisoners. The frontline German divisions had run up unusually high casualties. But there had been no breakthrough, not a hint of it, and the war went on much as before, except that there were an extra 100,000 French casualties. The French soldiers were bewildered and, in some cases, broken in spirit. As Correlli Barnett wrote in The Swordbearers, Nivelle had aroused exaggerated hopes. French politicians were appalled. They didn’t need to look for a scapegoat. Nivelle had nominated himself in advance.

He fell into depression and turned on his subordinates. When he told General Alfred Micheler he wasn’t trying hard enough, Micheler replied: ‘You wish to make me responsible for this mistake – me, who never ceased to warn you of it.’ Haig treated Nivelle graciously. He didn’t want the French offensive called off. This would give the Germans time to recover and perhaps interfere with his plans to attack at Ypres. But Nivelle now really had no say in what he was going to do. The politicians owned him the way a bank owned a defaulting mortgagor.

The Nivelle offensive petered out early in May. Frances Stevenson, Lloyd George’s secretary and mistress, wrote in her diary: ‘Nivelle has fallen into disgrace, & let D. [Lloyd George] down badly after the way D. had backed him up at the beginning of the year. Sir Douglas Haig has come out on top in this fight between the two Chiefs, & I fear D. will have to be very careful in future as to his backings of the French against the English.’

Nivelle was sacked shortly afterwards. He was eventually appointed commander-in-chief in North Africa. He had risen without trace; now he was going to disappear the same way.

Gough wrote in The Fifth Army that Nivelle had become ‘the victim of his over-elaborate promises. I wonder what were the thoughts of Mr Lloyd George when he heard of the failure and fall of the military genius to whom he had endeavoured to hand over the British Army? But this disillusionment did not, unfortunately, induce Lloyd George to place more confidence in Haig or to work more loyally with him; nor had he the courage on the other hand to dismiss him.’

GENERAL PÉTAIN HAD been made Chief of the General Staff less than a fortnight after the Nivelle offensive began. No-one was quite sure what this meant. What his appointment was really about was the undermining of Nivelle. On May 15 Pétain replaced Nivelle as French commander-in-chief on the western front. Ferdinand Foch, a fiery soldier who had thought deeply about the psychology of war, became Chief of the General Staff. The signal Foch was said to have sent during the battle of the Marne in 1914 had already gone into military folklore: ‘My centre is giving way, my right is falling back, situation excellent, I am attacking.’

Pétain was a realist with strong streaks of pessimism and kindness. Such people are not always the best leaders in war. Asquith had been too ‘civilised’: he could not declaim the bloody rhetoric of war with the naturalness of a Billy Hughes. Part of Churchill’s genius as a war leader twenty-five years later was his skill at persuading people to ignore unpleasant facts. Pétain, a farmer’s son, thought he had discovered the unpleasant facts about the Great War as early as 1914 and he didn’t want to ignore them. He saw few chances for breakthrough. Pétain understood earlier than most that breakthrough could occur only if one had enough artillery to paralyse the German defenders. He had seen more of the war on the ground than Haig or Gough. He not only had sympathy for the common soldier: he thought he understood him, and probably did. When he commanded at Verdun, during the worst of times, his heart lurched when he saw young men, high on enthusiasm, marching towards the furnace. And then he watched them coming out of the line. ‘Their stares seemed to be fixed in a vision of unbelievable terror … they drooped beneath the weight of their horrifying memories. When I spoke to them, they could scarcely answer.’

Haig had a long talk to Pétain shortly after the Frenchman came to power. ‘I found him businesslike, knowledgeable, and brief of speech,’ Haig wrote in his diary. ‘The latter is, I find, a rare quality in Frenchmen!’ In truth they had little in common. Pétain believed in limited attacks on narrow fronts, not grand offensives like the one Haig was contemplating for Ypres. Pétain wanted to wait for the Americans. Haig wanted to be unrelenting.

At other times Pétain might have been an unsuitable candidate for his new post. If Haig and Gough believed too much in ‘dash’, Pétain didn’t believe in it enough. He had an impressive presence but he lacked theatrics. He perhaps cared too much about the young men he sent out to die.

Yet he was right for this moment, just as he had been right for Verdun at its worst. All armies have a breaking point. Nivelle’s offensive had turned the French army sour, just as the Tsar’s blunders had turned Russian soldiers into deserters and revolutionaries. The Nivelle offensive had no sooner ended than mutinies broke out among the 2.8 million weary men of the French army.

‘MUTINIES’ IS THE noun most commonly used. It may not be quite the right word. It is hard to know what is. Unlike their Russian brothers, the French did not walk away from the front or murder their officers. The mutinies just happened naturally, in a regiment here and another there. They eventually spread to fifty-five divisions, half the army, yet no one person or political group was orchestrating them. They were more like strikes or demonstrations. They usually began when men were ordered back into the line. The men would refuse and many would get drunk on cheap wine. They might break windows, throw stones, jostle officers and hold meetings. A handful might head for the nearest railway station. There would be demands for more leave and better food. The Internationale would be sung. A red flag might be produced. Order would be restored. Then an identical incident would start in another regiment.

Pétain by late May was briefly looking at the possibility that the whole army would collapse. The French had 109 divisions on the western front, compared to Britain’s sixty-two, which included the contingents from the dominions. If the French collapsed, Britain had no chance of holding off the Germans. France was much more war-weary than Britain, partly because it had lost nearly twice as many men.

Pétain knew what had set the mutinies off and he quickly told Painlevé, the War Minister. Nivelle, Pétain wrote, had aroused false hopes. His wild promises had been ‘broadcast as far as the soldier in the ranks’. Then there had been the shambles after the opening day of Nivelle’s offensive: troops marched here and there, attacks ordered and postponed, nerves tested and frayed, defeatist talk in the Paris press. But Pétain also knew he could not condone breaches of discipline. Armies were not democracies; they could not function if they were being subverted from within.

Pétain set out to do two things. He punished the ringleaders of the mutinies and restored discipline. And he tried to redress the men’s grievances. Courts-martial were set up and eventually death sentences were passed on some 400 to 500 men. Around fifty sentences were carried out; some convicted men were sent to penal colonies. Pétain reformed the leave system. All were guaranteed seven days’ leave every four months. Pétain told the War Ministry to build 400,000 bunks and ordered that mobile cookers be placed as close to the front as possible. He decreed that the wine ration be stopped the day before troops departed for the front. He implied, but did not say outright, that there would be no major offensives. He thus also implied that he was not Nivelle, who many soldiers now called ‘the drinker of blood’. Pétain went around the divisions, talking to the men as well as the officers and fixing them with his calm blue eyes. He didn’t try to charm the rankers or pretend he was one of them, but he left an impression of trust and concern.

And he averted a crisis. The British historian John Terraine wrote that the men felt they could trust Pétain with their lives. ‘There was, in fact, a kind of unspoken compact between him and them: they would agree to obey; he would see to it that their obedience was not abused.’

By mid-July the mutinies had stopped, but the French army was not what it was. Patriotism was alive; it did not, however, run to big attacks, just stolid defence and an acceptance that the war would go on and so would life and both would mostly be miserable. For the rest of 1917 the British would have to do the attacking.

Haig might have been concerned about what support he could expect from the French for his Ypres campaign had he known how bad the mutinies were, but he didn’t. The first reference to them in his diary is on June 7, when Pétain told him two divisions had refused to return to the front. Haig was still discovering details in November. He apparently told Lloyd George nothing of Pétain’s troubles.

The most astonishing thing of all was this: the Germans didn’t know the mutinies were going on, which perhaps says much about the Kaiser’s intelligence arm. Had the Germans known, the shape of the war in 1917 might have been different.

WE DON’T KNOW whether General Otto von Moser, the German corps commander, was much like General Gough, but he now began organising an attack on the Australians that was straight from the script Gough had dashed off for First Bullecourt. It was April 13, two days after that battle. The 2nd Australian Division now held the front facing Bullecourt and Riencourt. The 1st Australian Division held a huge front, some seven-and-a-half miles, on the right of the 2nd, facing Quéant and several other villages behind the Hindenburg Line. Like Gough, Moser liked to ride his horse as often as possible. He had just returned from doing so on the 13th when his chief-of-staff told him that he was being sent a fresh division. Headquarters thought his front was about to be attacked, presumably by Walker’s 1st Division. The chief-of-staff also offered the thought that the best plan would be to attack the Australians first.

Moser lunged at the idea like Gough reaching for a tank. He telephoned army headquarters and outlined his scheme. According to his memoirs, the answer came as ‘swift as lightning’. Yes, he could carry it out. He would be given another two divisions to do so.

Moser worked frantically on a plan. The orders were only sent to divisional headquarters the following afternoon. The attack was to go in at 4 am the day after, April 15. The four divisions would go for the villages of Lagnicourt, Noreuil, Morchies, Boursies, Doignies, Demicourt and Hermies. Moser knew that the Australian artillery had batteries near Noreuil; he didn’t know there were also batteries at Lagnicourt. His infantry would rush forward like storm-troopers, destroy artillery pieces, cause panic and confusion, then withdraw in darkness on the 15th.

The Australians were vulnerable. Gough had already decided that he was going to attack in the Bullecourt re-entrant again but he wanted the Germans to think the assault might come from anywhere. That’s why he pushed the 1st Division’s line out far to the right. Outposts of four to seven men held the long front there. In the valleys behind them lay the guns of the Australian artillery. No-one had given much thought to protecting them. The mentality of trench warfare lived on. Attacking infantry seldom made it to the other side’s guns and history said that the Germans seldom attacked anyway.

Before dawn on April 15 the Australians in the outposts were astonished to see Germans advancing. The 1st Division was being attacked along the whole seven-and-a-half miles of its front by four German divisions. The battlefield fell into chaos. The Germans swarmed between the Australian outposts. Soon they were all around them and the Australians began to run out of ammunition. Lieutenant Charles Pope, a former London policeman, heard the Germans behind him. He sent a private back for more ammunition. After going 100 yards Private Gledhill, a farmer from Western Australia, ran into a line of Germans creeping forward. He skirted them, then ran into two Germans, who, as he put it, didn’t bother him, just as he didn’t bother them. Next he came upon a German lying down, who stood up and raised his arms. Gledhill swore at him and kept going. He reached company headquarters but could not get back with reinforcements and ammunition. ‘Hang on’, Pope shouted to his men. Then he was shot dead.

The light was still murky. Germans going forward passed Australians going backwards. They could hear, but not see, each other. The Germans broke the Australian line in front of Lagnicourt and captured several batteries. The gunners had not expected to be attacked by infantry. They had left most of their rifles back at the wagon lines near Bapaume. They were now told to remove the breech blocks and dial sights from their guns and retreat, which they did with some panic. The Germans were threatening other batteries near Noreuil. It was, as the British official historian observed, ‘a very ugly situation’.

The Germans had broken through only at Lagnicourt. It was a big breach but the delaying actions fought by the outposts had bought time. Captain James Newland, a career-soldier from Launceston, Tasmania, set up a defensive post to the east of Lagnicourt. Battalion headquarters was not far behind him. Here cooks, batmen and other headquarters staff picked up rifles and joined the shooting war. The Germans had now pushed a salient one-and-a-half miles into the Australian lines around Lagnicourt.

Germans fired into Newland’s party from the front and the rear and tried to set up a machine gun on a flank. Sergeant John Whittle ran out alone and not only killed the machine gunners but also brought back their gun. He, Newland and Pope were all later awarded the Victoria Cross.

It was not yet 8 am. The Germans hesitated when Australian reserves came up and began blazing away at them. Now they were being shot at from all sides. They had got into Lagnicourt easily enough but couldn’t get out the other side. The counter-attacks intensified. The Germans began to break for home. Others surrendered. One handful of Australians, some of them unarmed, brought in 147 prisoners. When the Australians recovered the batteries the Germans had seized they found only five guns had been wrecked. The Germans, it seemed, had spent much of their time foraging for food and souvenirs in the Australian dugouts.

The Australians re-occupied most of their old positions. General Moser’s attack had failed. The Australians had suffered 1010 casualties, the Germans around 2300. Some of the German prisoners complained that they had been thrown into the assault at short notice and without a chance to look at the ground. Moser claimed the attack forced the enemy to bring up strong reserves. In truth it caused no movement of reserves and had no effect on the battle of Arras. Four thousand Australians in the front area had turned back 16,000 Germans. The only mistake the Australians had made was the failure to protect their guns.

PRIVATE ERIC PINCHES, a Queenslander, had rushed a German machine gun. Its crew surrendered and Pinches won the Distinguished Conduct Medal. He was wounded the following month in the battle that would become known as Second Bullecourt and died the next day. His name appears on the wall of the Australian National Memorial at Villers-Bretonneux. Many people want to see Private Pinches’ name and even take a photograph of it. He was sixteen years old. He may have been the youngest Australian to die on the western front. There is no way of knowing for certain. It was a big war and many young men lied about their age.

PRIVATE BILLY WILLIAMS of the 2nd Australian Division was going to be in Second Bullecourt. This time Gough would use the 2nd Division. Williams first enlisted in New South Wales as a fourteen-year-old. He brought along forged papers and signatures. He was passed fit but, as he put it, sent home to his mother. ‘When I was 15 years and 5 months,’ he explained in 1980, ‘I blackmailed my Mother with the threat that I would enlist under another name, and she would never know where I was because I knew I could pass the medical. She signed with much reluctance and with the remark that it would teach me a lesson, and that I would be glad to get back to home and Mother. There were many times when I wished just that …’ The doctor who certified Williams as fit knew he was only fifteen. ‘He delivered me into the world. But he was a “government man” by then.’

Preparations for Second Bullecourt were more thorough than for the first battle, although no-one seems to have given much thought to the obvious: why attack again in a re-entrant? Williams said the troops rehearsed the assault for several days behind the lines.

There were lines of white tapes laid out on the ground to represent the German front lines. Each line was referred to as OG (Old German) from No 1 to No 8. We were divided into 8 waves and each wave had an objective. The first wave moving forward under a protecting barrage were expected to take OG1, and then the second wave had to frog hop over No 1 wave and take OG2 and so on up to OG8. Most of us thought the rehearsal was farcical when the Light Horse were brought on to the scene at night rehearsals, and bore lighted torches in front of the moving troops. The moving torches represented covering barrage. I am sure that ‘Fritz’ knew our every move, because when the real thing started at 3 am May 3rd 1917, both barrages on each side opened up simultaneously. It was so thick that I wondered how a flea could come through it unscathed.

When the battle opened a lump of shrapnel tore into Williams’ right shoulder blade and skidded off to lodge on a rib. He was sixteen years and seven months when they carried him out that day. When his war ended he was seventeen years and eight months, still too young to enlist.

THE REHEARSALS AND other elaborate preparations didn’t mean that Gough had learned much from First Bullecourt. He had wanted to attack again on April 15, four days after the first assault had failed. Had this gone ahead, General Smyth’s 2nd Division would have been rushed into the re-entrant as rudely as the 4th Division had. But Allenby’s 3rd Army, to the north, was still too far back. Gough kept postponing the attack before finally settling on May 3, the day Allenby had set down for an advance on a fourteen-mile front, the widest attack ever tried by the British army in France. Bullecourt would be the right wing of this attack. Haig and Allenby were doing this to help Nivelle, who was resuming his doomed offensive to the south the next day. Haig thought Nivelle would almost certainly be sacked. With greater certainty he felt that the Nivelle offensive had already failed and would soon be called off. If so, there was little point in Allenby, with help from Gough, trying to reach Cambrai, because the French would not be surging up from the south to meet them.

Haig’s big attack of May 3 would become another of the Great War’s murderous gestures. It was, as the British official history notes, about holding the Germans to their ground and encouraging the French to keep their nerve. Haig’s mind was elsewhere. Arras was not going to work. Ypres beckoned.

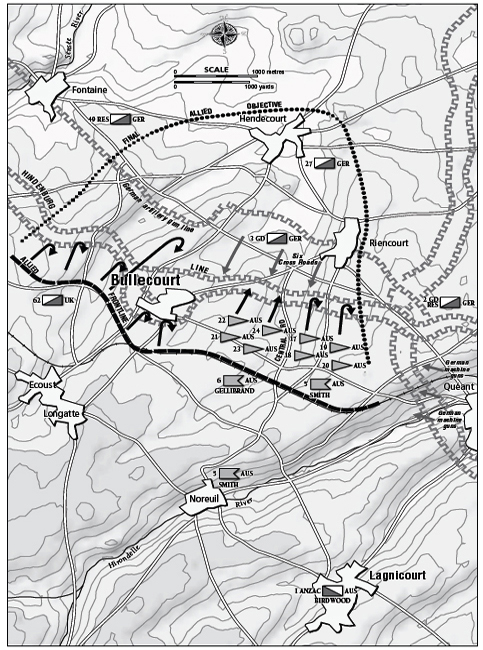

THE AUSTRALIANS WERE to attack over the same ground. This time John Gellibrand’s 6th Brigade would be on the left and Brigadier-General Bob Smith’s 5th Brigade on the right. This time Braithwaite’s 62nd Division would attack at the same time as the Australians and try to drive deep into Bullecourt village. Ten tanks would help with the British attack; the Australians didn’t want to see a tank on their front. Both divisions would advance 3000 yards in three stages. In the first the British would take Bullecourt and the Australians would retake the Hindenburg Line trenches in front of Riencourt. In the final stage the British would take Hendecourt and the Australians Riencourt.

This time the Australians would go in behind a creeping barrage and with ninety-six machine guns firing over their heads. The Anzac Corps heavy artillery had been reinforced with British guns from the north; its batteries had more than doubled to thirty-one. From mid-April the heavies reduced Hendecourt, Riencourt and Bullecourt to ruins, although the Germans could still shelter in cellars. Gunnery was all the time becoming more scientific. The order for the creeping barrage came as an elaborate map of which 300 copies were issued. But neither the staff at Anzac headquarters nor the gunners seem to have thought much of the German trenches in front of Quéant, which were largely untouched. These were only 1000 yards or so from the right flank of the Australians. True, there was a low hill between the Germans and the Australians, but the German machine gunners could still send grazing fire over the rise.

The rehearsals that Billy Williams wrote about took place near Favreuil on ground similar to the battlefield. Wire and tape were used to mark the German positions. Mounted men moved ahead of the troops to show where the creeping barrage would be landing. Aerial photographs of the German lines and the villages beyond were handed around. Gough and Birdwood turned up for a dawn rehearsal. Gellibrand noticed that bayonet scabbards made a loud flapping sound and ordered them tied down.

Zero hour was fixed for 3.45 am. This was a compromise. Gough had wanted the men to go at 4.20, when the first smudges of dawn were showing. The Australians wanted to go in the dark after the moon had set at 3.29. Braithwaite was worried that his British troops, who had never been in a major attack, would become lost in the dark.

The Australians from the two attacking brigades cast their votes for the federal election back home (which, as previously mentioned, resulted in a victory for Billy Hughes’ new Nationalist Coalition) and returned to the frontline in the opening days of a glorious spring. Splashes of green appeared on bare fields, the few trees that had survived the shelling began budding and the sun cast a soft and golden glow. These men, had they not been hardened by Pozières, might have thought this a time for hope and regeneration.

BILLY WILLIAMS MAY well have been right when he wrote that ‘“Fritz” knew our every move’. It is possible the Australians, without knowing it, had glimpsed the red-nosed aircraft of Manfred von Richthofen in the skies above Noreuil in the weeks before Second Bullecourt. The former cavalryman was swooping on British reconnaissance aircraft from a field just behind Bullecourt. April had been his best month for kills. He now had fifty-two, which made him the most lethal German flyer of the war.

The day before Second Bullecourt opened a German aircraft crashed behind the Australian lines. Australians ran to the plane to find one flyer badly wounded and the other extremely voluble.

‘What time is zero?’ he asked a Queensland farmer.

‘There’s no zero,’ the Australian replied. ‘We’re not thinking of attacking.’

‘Oh, we know you are,’ said the German. ‘What time do you start?’