Roses with carmine petals

The captured trenches at Bullecourt were built into the British lines and the place reverted to the norms of trench warfare. Bodies were buried, sentries posted and cookers brought up behind the front. Each side lobbed the odd shell on the other and riflemen blazed away at shadows in the night and longed for the rum ration. By June the Bullecourt front was like any other quiet sector. Yes, it was a rupture in the Hindenburg Line, but it led nowhere. The last days of this battle had been about bluff. Bullecourt became a ‘local objective’, not, as it had once been, a step in a journey of breakthrough. When Second Bullecourt was only two days old Haig was saying he wanted to keep the Germans in doubt about where he would start his next offensive. He wasn’t much interested in what was happening at Bullecourt. His mind was fixed on the Ypres salient and the high ground that curled around it.

Haig, with justification, believed that his British empire army was the only robust arm of the allied coalition. The Italians were badly led and inclined to muddling, the Russians were in turmoil after the revolution, the French seemed incapable of mounting an offensive (Haig didn’t yet know the extent of the mutinies), and the Americans hadn’t arrived. Haig, moreover, had little confidence in Third Ypres: the battlefield his own navy, which was clamouring for the Belgian ports to be cleared by the army. Many thought the navy was too cautious, that it wanted to win the war without fighting. Haig called Jellicoe, the First Sea Lord, an ‘old woman’.

Lloyd George, also with some justification, didn’t believe in Haig. He refused the field-marshal (Haig had been promoted earlier in the year) substantial reinforcements for his Ypres campaign. Lloyd George had ideas that the war could be won from Italy; he also placed an absurd importance on the capture of Jerusalem. Still, one has to be careful in trying to characterise Lloyd George’s attitude. He was not against the battle that would be designated Third Ypres. He didn’t like the idea; he didn’t like Haig or the prospect of another Somme-like casualty list. But, when it came to grand strategy, he lacked the confidence to overrule Haig and Robertson (who, it should be said, didn’t believe in the Ypres offensive as ardently as Haig). Lloyd George simply wasn’t for Ypres.

Haig lacked the Prime Minister’s quickness of mind; he was stiff-necked and dull. But he was full of resolve in a way the Prime Minister was not. Haig didn’t lapse into the self-doubts that bothered men of sharper intelligence. And, most of the time, Haig, the amateur politician, seemed to best Lloyd George, the amateur strategist, not through brilliance but with a tactic he understood well: attrition. Haig prevailed by stubbornness, by force of character rather than force of intellect. He was always in front of you, saying in awkward and often incomplete sentences exactly what he had said yesterday. Lloyd George kept changing his mind and Haig kept saying the same things. Haig had a plan and he challenged you to come up with a better one. And now he was stronger because he had been right about Nivelle and Lloyd George had been wrong. If the Prime Minister was brighter, Haig was doughtier. He didn’t, as some have suggested, think of trying to bring Lloyd George down. If he could avoid it, he didn’t think about Lloyd George at all. The Prime Minister lived in a world he didn’t understand and didn’t much want to.

So Third Ypres – or Passchendaele as it later came to be known in folklore and nightmares – came about because Haig and the hand-wringers at the Admiralty wanted it. It came about after attempts at breakthrough elsewhere – on the Somme, along the Chemin des Dames and at Arras – had failed. It came about because it was one of the few options left and had definite and worthy objectives that were not present in the Somme campaign. It came about because the War Cabinet wasn’t sure what to do. Above all it came about because Lloyd George, while he seldom felt comfortable about it, lacked the resolve to say no to it.

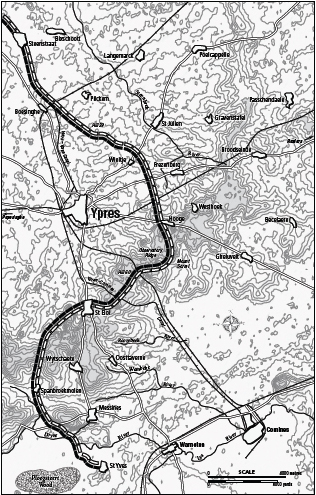

The low ridges that Haig wanted to capture at Ypres were roughly in the shape of a sickle that swept around the ruined city. As a first step he would use sixteen divisions and lots of artillery to capture a ridge and a village on the handle of the sickle. The village was called Messines.

Sir Herbert Plumer would attack Messines with his 2nd Army. Plumer, as requested, wrote a scheme for the first stage of the push to the coast. It was a step-by-step plan, careful and typical of Plumer. Haig thought it too careful. He wanted to see bold arrows on a map, to hear the word ‘hurrosch’. Plumer always seemed to come up with a scheme that was a few thousand yards short of Haig’s idea of glory. Haig eventually decided that Gough should take over the main offensive after Messines: Gough, who didn’t take staff work too seriously, who had neither the organisational skills of Plumer nor his even disposition, who didn’t know the salient well, who had just blundered at Bullecourt and was almost certainly Haig’s least competent army commander.

The coming of Gough meant there would have to be a gap of seven weeks between Messines and the offensive towards the coast. The Germans would have time to work out what was happening.

JOHN MONASH HAD set up his headquarters in a château north of Armentières. He hung photographs of his garden at Toorak on the walls. Part of him was thrilled by his elevation to command of a division – he had always craved recognition – but another part was homesick. On March 7 General Godley told Monash his 3rd Division would be part of the attack on Messines. The New Zealanders would also take part. Both divisions were in Godley’s II Anzac Corps. Monash at once began working on a scheme that became more and more intricate. He called it ‘Magnum Opus’.

He interrupted this to take leave on the Riviera, where he panted up donkey tracks to old villages ‘past beautiful villas all smothered in flowering creepers, and later through olive forests and lemon groves’. He watched fishermen and took the tram to Monte Carlo where he enjoyed a performance of The Barber of Seville at the opera house. His eyes missed nothing. The villagers in the mountains looked ‘just as if they had stepped out of a picture, the men with thick stockings, plush corduroy breeches, blue kummerbund and sash, Garibaldi shirts, and Tyrolean hat, the women with bulging skirts, aprons, and flat chacot, all carrying great loads on their heads – like Arab women’.

Back at the château he worked on Magnum Opus and on April 15 showed it to his three brigadiers and told them to discuss it with their battalion commanders. He then began working on specific tasks for platoons and even sections. Monash wanted to know where the man from the YMCA was going to set up his coffee stall. Soon ‘Magnum Opus’ was six-inches thick. ‘Wonderful detail but not his job’, Major-General Charles ‘Tim’ Harington, Plumer’s chief-of-staff, said.

Monash wrote to John Gibson, his partner in a reinforced concrete business in Melbourne. He needed to tell Gibson that there was no prospect of him returning home to help with the business.

Any attempt to desert my post is unthinkable … even if I could have had my discharge for the asking, and this is most assuredly not the case, every dictate of honour and proprietary prevents my even contemplating such a thing. For myself I am very heartily sick of the whole war business. Its horror, its ghastly inefficiency, its unspeakable cruelty and misery have always appalled me, but there is nothing to do but to set one’s teeth and stick it out as long as one can.

Monash kept refining his plan. He had been in several badly planned attacks at Gallipoli under Godley, who was a lazy commander there and no better here. Godley’s genius, if he possessed any, lay in distancing himself from failures. This time Monash was doing the work Godley couldn’t do. It was a set-piece and Monash had time to get everything right. Bean wrote in the official history: ‘His Jewish blood gave him an outstanding capacity for tirelessly careful organization.’ Bean had interesting ideas about genetics.

Haig came to inspect the division. During the preparations a Jewish officer was thrown from his horse. Haig seemed distant and unimpressed during his visit, although he wrote afterwards that Monash was a ‘most thorough and capable commander’. The mood in the 3rd Division officers’ mess that evening was subdued. Monash rose to read the weather report.

‘A heavy dew fell this morning,’ he began.

LIEUTENANT PHILLIP SCHULER, known to his friends as Peter, was in Monash’s divisional train, looking after baggage and food supplies, and it seemed odd that he should be there. He was about to turn twenty-eight, tall, olive-skinned and handsome. Everyone seemed to like him. His father, Frederick, had come to Australia from Germany as a child and was editor of the Age ; his mother, Deborah, was blind as a result of a fall down stairs. Phillip had started a law degree and failed, mainly, it seems, because of his busy social life. Phillip joined the Age and quickly proved that he was a natural writer. He liked books and plays and dining out and was the youngest member of the Savage Club, then a meeting place for Bohemians.

Schuler left with the first convoy of Australian troops in 1914 as the Age correspondent. Sir Ian Hamilton thought him a ‘delightful personality’. Schuler wrote a series of articles about the scandalous treatment of the wounded taken off Anzac Cove after the landing.

What did they come back to? The best attention and comfort that medical skill could provide? No! The bare iron decks of the transports where they had been living for the last three weeks. To medical comforts? No! To the old grey blankets they had just discarded and the decks. To milk and soft food for those unable to take the iron rations and bully beef? No, to their ordinary rations.

He reported that wounded had been left untreated aboard a hospital ship in Alexandria because the medical staff ashore had gone to the races. Schuler’s reports were not only accurate; they were foremost among the few critical pieces published while the Gallipoli campaign was actually going on.

Schuler’s photographs from Lone Pine were haunting and remain the best-known images of Gallipoli. He returned to Australia to write, in ‘fever heat’, the book Australia in Arms, the first long account of the Gallipoli campaign. Monash read the proofs of the book on Salisbury Plain. He thought the manuscript more accurate than Hamilton’s dispatches.

Schuler had tended his credentials as a journalist and writer and they were better than those of just about anyone else in the country. He might, one would have thought, have been given accreditation to cover the war on the western front. Instead he enlisted, and not as an officer, as he could have been easily enough, but as a driver. He was sent to Monash’s 3rd Division. Why did he swap the relative ease of life as a war correspondent for that of the lowliest soldier? And there was another mystery. He had met a ‘beautiful and gifted’ woman in Cairo, a widow with two children. According to Roy Bridges, a colleague of Schuler’s at the Age, they were engaged.

Schuler had been promoted to lieutenant by the time Monash was planning for Messines. He wrote to Bridges just before the battle opened. The letter ended: ‘Keep on remembering.’

HERBERT PLUMER, SIXTY at the time of Messines, an old Etonian and an infantryman, was an English gentleman in the best sense of the word. A staff officer once suggested to him that a certain person was too much of a gentleman to handle the job for which he was being touted. Plumer screwed his eyeglass into his eye, looked at the staff officer, smiled, and said: ‘Can you be too much of a gentleman?’ It is often said that, because of his looks, Plumer was the inspiration for David Low’s cartoon character Colonel Blimp. He wasn’t, but he could have been. Philip Gibbs, the English war correspondent, described him thus: ‘In appearance he was almost a caricature of an old-time British General, with his ruddy, pippin-cheeked face, with white hair and a fierce little white moustache, and blue, watery eyes, and a little pot-belly and short legs.’ His men called him ‘Daddy’ and his friends called him ‘Plum’, and he was almost certainly the best of the British army commanders. Plumer was thorough and measured in everything he did and he understood the nature of the war and the primacy of artillery. He didn’t see cavalry galloping through gaps; he worried about casualties. Haig thought Plumer sound but perhaps lacking the ‘real offensive spirit’.

Plumer had been in charge of the Ypres front since the spring of 1915 and, as the British historian John Terraine put it, he and Harington, his chief-of-staff, had created an atmosphere that was unique. John Charteris, Haig’s head of intelligence, wrote: ‘Plumer and Harington are a wonderful combination, much the most popular, as a team, of any of the Army Commanders. They are the most even-tempered pair of warriors in the whole war or any other war. The troops love them … Nobody knows where Plumer ends and Harington begins.’ Philip Gibbs said of Harington: ‘For the first time, in his presence and over his maps, I saw that, after all, there was such a thing as the science of war, and that it was not always a fetish of elementary ideas raised to the nth degree of pomposity, as I had been led to believe by contact with other generals and staff officers.’

Despite the long casualty lists from the battles of 1915, from the Somme and from Arras, many of the allied generals were starting to understand how to fight the first war of the industrial age. They knew artillery pieces had to be concentrated, so that barrages were heavy enough to keep the Germans away from their machine guns. They accepted the need for creeping barrages. More thought was being given to knocking out German artillery pieces – counter-battery work. Gunners were experimenting with flash-spotting and sound-ranging as ways of locating the German batteries. The machine-gun barrage was becoming more common. More time was being spent on preparation. Aircraft were becoming more important as artillery techniques became more sophisticated. The British had twice as many planes in the Messines area than the Germans. The realisation had come: it took more than ‘character’ to break into the enemy’s trenches.

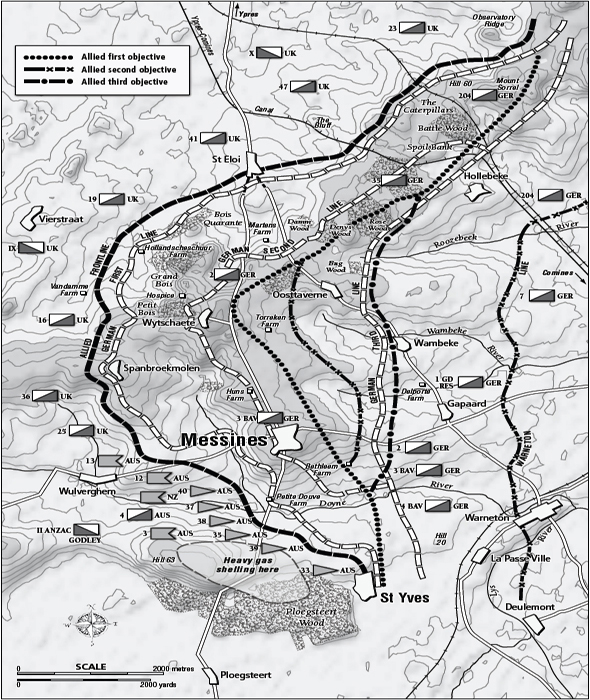

Plumer brought all these ideas into his plan to capture Messines. He had two extra advantages. This was a set-piece battle with limited objectives and he had plenty of time to plan it. And he had a weapon that had never been used on this scale in the war before. Since 1915 his men had been tunnelling under the German lines. The Germans didn’t know it but they were sitting on close to one million pounds of explosives.

British, Canadian and Australian tunnellers had pushed more than twenty galleries out under the German lines. Several were more than 2000-feet long. Most were between fifty and 100 feet below the surface. The shafts had been sunk well behind the British lines. The signposts said they were ‘deep wells’ and the spoil that came up, a distinctive blue clay, had to be hidden so that German airmen would not spot it.

The clay, similar to that which was excavated to build the London underground railway, was difficult to mine with mechanical diggers. Men with spades and picks did most of the work. One would lie on his back on a plank and would use both feet to drive a spade into the face. Another man would gather the clay into a sandbag and a third would drag this back to the trolley rails.

More than 173 miles of new railways had been laid behind the lines. For the first time light railways carried ammunition right up to some of the heavy batteries. And Plumer had lots of batteries. Here was another change. Artillerymen now related the number of guns to the length of trench to be attacked. Plumer had 2200 guns for his ten-mile front, 756 of them heavies. He had twice as many guns as the Germans. A year earlier, on the first day of the Somme offensive, and on a wider front, the British used only 1400 guns, of which fewer than 400 were heavy or medium.

The business of killing was being reduced to a mathematical formula.

PRIVATE GEORGE DAVIES, a signaller, came up to the front with Monash’s 3rd Division. Davies didn’t like war, scientific or otherwise. He was an ardent Methodist and often preached at church services and helped with burials. The men seemed to like him, but he wrote early in 1917 that their swearing, drunkenness and general immorality horrified him. He was an acute observer of small but telling incidents. He recalled that the day before Messines opened a soldier who had never been in a big attack before asked him the simple question: ‘Do you take your overcoat?’

The same day Davies wrote to Willie, his adopted brother in Australia. If he lived through the battle, he told Willie, he would do ‘all I can to crush any military tendencies in my nation’. He would ‘uphold the very highest and best socialism’ and try to make his life more like Christ’s. But Davies had a premonition of death. He told Willie he was leaving him his war diary and his books. ‘All my Poet’s works are yours … I hope you will read them as they will make your life beautiful and sweet.’ He also left Willie his bicycle.

Then he wrote to his mother. ‘If I live I shall stand by red-hot socialists and peace cranks to stop any further wars after this one, but while I am at it I will fight like only one facing death can fight.’ Davies survived the opening of the battle. He was killed when it was five days old.

Lieutenant Walde Fisher, a law student and tutor, also came up with Monash’s division. He survived. He wrote a highly readable diary for the months preceding Messines. One day on the Armentières front he and his men could not get a drain to run. A man went down to find the obstruction. ‘That’s the silly ------ who blocked it,’ he exclaimed. ‘That’ was the decaying body of an officer of the Sherwood Foresters. Fisher noted in May: ‘One of our chaps got 29 wounds yesterday, and was as bright and cheerful as ever. The M.O. asked him: “Well, and what have you got?” “Everything,” he answered, “except the bloody nose cap.” He may pull through, Casey is his name.’

Captain Bob Grieve, a twenty-seven-year-old commercial traveller from the Melbourne suburb of Brighton, heard the sounds of the nightingale and the cuckoo for the first time while waiting in Ploegsteert Wood for the battle to start. He wrote that on the night of June 6 he and his men shook hands all around and started for the front and the attack. They hadn’t gone far before they realised the Germans were firing gas shells. They could smell the gas and the shells made a distinctive pop as they exploded. The men pulled on their masks, immediately became half blind and almost suffocated because their lungs were heaving from the long walk through the barrage carrying ammunition and tools. Grieve said it was pitiful to see horses and mules gasping for breath.

Lieutenant William Palstra, a twenty-five-year-old accountant from the Melbourne suburb of Surrey Hills, had stared at a plane flying overhead while he was training on Salisbury Plain. He decided at that moment that he wanted to be a pilot. Soon after he began sending off applications to join the flying corps. But here he was at Messines, leading a platoon in Monash’s division up to the start line. Then the gas came. ‘Have to wear box respirators,’ he wrote. ‘The remainder of the march … was one long drawn-out hell.’ Some men, he said, were gassed when their masks slipped. The hours that followed were worse than anything that happened in the three days of fighting that were to follow. ‘The night was fairly dark, one’s gas mask glasses were continually becoming fogged with perspiration, one tripped over obstacles – barbed wire and groaning men.’ The gas took half Palstra’s platoon. The other half arrived at the start line, stripped off all their equipment and lay exhausted on the duckboards.

FIVE DAYS BEFORE Messines opened Harry Murray, walking his easy walk and wearing a slouch hat, received the Victoria Cross from George V in Hyde Park. A friend ‘smartened him up a bit’ before the ceremony. Murray was never one for spit and polish. Sometimes he wore his leather officer’s belt, known as a Sam Browne, with the buckle in the wrong place. The King spoke with Murray at length. Though he would have hated the thought, Murray was becoming famous. He had now won the Victoria Cross, two Distinguished Service Orders and the Distinguished Conduct Medal. Murray wrote that the King did not pin the medal on. It was hung on hooks that had been attached to Murray’s uniform beforehand. An official who took himself rather seriously told Murray the hooks had to be returned after the ceremony. ‘Evidently he had heard of Ned Kelly,’ Murray wrote.

He took a trip to Scotland, then returned to France. His 4th Division was the reserve division for the battle of Messines.

AT BULLECOURT THE Australians had been half the attacking force. Here they were a small part of a bigger and better-planned assault. Plumer was using nine divisions from three corps for his initial attack. Monash’s division was the southern flank of the whole attack; it would go for the lower shoulder of Messines ridge. Above it the New Zealand Division would take Messines village. The British 25th Division, loaned to Godley, would attack further north between Messines and Wytschaete village. The long-suffering Australian 4th Division, reinforced after Bullecourt, started out in reserve but was told shortly before the attack that it would be in action on the afternoon of the first day. Monash would attack with two brigades up, the 9th and the 10th. The 11th was in reserve.

Plumer had at first planned to take only the German frontline. This was 1500 yards away, in the valley in front of the ridge itself. Haig persuaded Plumer to go through the frontline and take Messines and Wytschaete on the first morning. In the afternoon the troops were to head down the reverse slope of the ridge and capture the German intermediate position known as the Oosttaverne Line, an advance of 3000 yards. Four-and-a-half German divisions held the ridge, which was dotted with concrete pillboxes. In other circumstances the German position might have been formidable. But this time the British artillery had done its job well; this time the bombardment bore a sensible relationship to what the infantry was being asked to do.

Wire-cutting had begun on May 21. By zero hour – 3.10 am on June 7 – most of the wire had been pulverised. So had the two villages and most of the German trenches. Many of the German guns had been knocked out by counter-battery fire. Only the pillboxes remained. The Germans were addled by the fury of the bombardments. One wrote: ‘All the trenches are completely smashed in … we are forced out into the open without any protection.’ And then there were the mines.

Nineteen of these went off over forty-five seconds at 3.10 am. It was the largest man-made explosion in history. One hundred and thirty miles away Londoners heard it as a distant roar. Fifteen miles to the east German soldiers in Lille ran in panic, fearing an earthquake. Buildings swayed and window glass fell into the streets. Perhaps 10,000 Germans died as the mines went up, some of them simply atomised. The earth trembled, a wave of hot air ran up the ridge and beyond, black clouds of smoke and dust rolled over the German rear positions and blotted out the light of the sinking moon, craters hundreds of feet wide opened up and the sky rained clods of Flemish clay. The Germans who survived were half-mad and mostly wanted to surrender. Philip Gibbs watched the spectacle.

The most diabolical splendour I have ever seen. Out of the dark ridges of Messines and Wytschaete and that ill-famed Hill 60 there gushed out and up enormous volumes of scarlet flame from the exploding mines and of earth and smoke all lighted up by the flame spilling over into mountains of fierce colour, so that the countryside was illuminated by red light.

Bob Grieve watched a big mine go up on the Australian front. The earth rose like a huge mushroom, he wrote. ‘Debris of all description rained down with dull thuds for quite a time, then all was over.’

A German witness saw ‘nineteen gigantic roses with carmine petals’ rise slowly and majestically out of the ground. After the explosions the Germans on the rise leading to the villages sent up white and green flares. They were asking for artillery support. But the British gunners had already hit the German batteries with gas shells and high explosives. By the time the German counter-barrage began falling on the assembly areas, most of the British and dominion troops had left. In no-man’s land they encountered dazed Germans and hardly any machine-gun fire. They crossed the cratered valley and begun to push up the hill with dust swirling in front of them and their own barrage shrieking overhead. No British battle of the war had begun with such promise.

Lieutenant Palstra watched a mine on his right go up ‘like a volcano, the earth coming down like a hailstorm for minutes afterwards’. Palstra and his men followed the creeping barrage. ‘The moment we entered his wire the Hun abandoned his guns and left his trenches in a solid line. Our men stood in that wire and shot them down …’ Palstra found mineral water and cigars in the pillboxes and handed them out among his men. So many senior officers were killed or wounded that Palstra ended up commanding his battalion for two days. Afterwards he was awarded the Military Cross. But he still wanted to be a pilot.

THE AUSTRALIANS WERE unlucky. The gas shells that fell among them as they made their approach march through Ploegsteert Wood caused at least 500 casualties before the formal battle began. Some gas-affected men retched and collapsed and others fell asleep on reaching the assembly trenches, but the Australians had still managed to arrive before zero hour.

Charles Bean was heading towards Ploegsteert Wood with Malcolm Ross, the official New Zealand correspondent, and a photographer when they smelled gas. ‘Pretty strong,’ Bean scribbled in his tiny grey notebook. ‘We put our helmet nozzles in mouths … As we went up thro wood … gas shells began to fall fast – pot, pot, pot all around. We stopped and put on [gas] helmets – photographer tore his off presently – we were going too fast. I made him put it on once again. We tried them off presently but Ross was sick at once. We got up without accident – trenches were pretty well steeped in gas.’

Bean waited for the mines to go off. He kept making notes: ‘Men have had their breakfast … Moon bright … Red of dawn over Messines … Our bombt begins … Mine after mine.’

THE PASSCHENDAELE CAMPAIGN, of which Messines was the start, has produced a considerable literature, much of it about sacrifice and sadness, mud and muddling. This is right enough: there is an analogy of sorts, as we will see, between Passchendaele and the Passion of Christ. For clarity of analysis, however, nothing matches Robin Prior and Trevor Wilson’s Passchendaele: The Untold Story. The authors divide the Messines attack into four phases: the capture of the German frontline; the taking of the crest of the ridge, including the two villages; the consolidation of the positions won; and, finally, the bit Haig had added on, the advance to the Oosttaverne Line. The first three phases went well.

After the mines sent crimson fire into the sky some 80,000 British and dominion troops headed for the ridge, dust clouds from the mines rearing in front of them. Sometimes the dust was so thick that compasses had to be used. Never had German troops seemed so demoralised. Bean reported that on Monash’s front the Australians found a few Germans cowering in the front trench. Many had fled, leaving behind a trail of abandoned rifles, ammunition, cigars and scraps of food. And many quickly surrendered. An Australian lieutenant said the Germans attempted to embrace their captors. ‘I have never seen men so demoralised,’ he said.

To the north the 36th (Ulster) Division, which had fought so bravely on the opening day of the Somme offensive, went over the parapet after the Spanbroekmolen mine, the second biggest of the nineteen, went off. They met no opposition. The Germans there were either dead or out of their minds. Lumps of blue clay the size of farm carts lay around the mine craters.

All along the line the German front trenches were taken in the thirty-five minutes laid down by the barrage timetable. Casualties were light, astonishingly so for an operation of this sort, as though the history of the Great War was being defied, which it was.

The New Zealanders went for Messines village, where machine guns were still chattering. The Germans had turned the village into a fortress. Just about every cellar had become a dugout and five concrete blockhouses had been erected. The Germans here wanted to fight. But the New Zealanders, showing that same doggedness that had marked their time at Gallipoli, methodically took the village, flushing out the Germans with smoke bombs. They captured the commandant and his staff in a dugout below what had been an orphanage. Wytschaete village, also fortified, fell to two Irish battalions.

The second objective had been taken, not as easily as the first, but easily enough by the standards of this war. The violence and accuracy of the barrage had smothered German attempts at counter-attack. The British and dominion troops owned the ridge from north to south. Beyond the edge of the plateau they could see lush country to the east: hedgerows, untorn grass, trees with leaves on them and, far away, the steeple of Menin. Battalions slated for the afternoon advance to the Oosttaverne Line began to assemble and move up. In the case of the Australians this meant parts of General Holmes’ 4th Division and Captain Grieve’s battalion of Monash’s division.

Bean and others have left us with sketches of the scene in the early morning. Cavalrymen on the crest north of Messines. A sky crowded with British aircraft. Dozens of British observation balloons, like huge grubs, as one officer put it, searching for artillery targets. Maori pioneers below Messines digging in the Flemish clay. Dust plumes from shell-bursts up on the plateau. Tanks grumbling and groaning. New battalions lining up on flags marked with their colours. Artillery teams trotting back to the music of tinkling chains.

And there was something else about this battle, something one could not see. It was eight hours old and this time, this once, the generals running it had not lost control. They knew what was happening and, for once, what was happening was what was supposed to happen.

Grieve came up for the afternoon attack, past dead Germans and ruined farmhouses and unbroken pillboxes. He reached Betlhéem Farm, south-east of Messines village, and found Australians from the morning attack digging in. ‘Digging away for all they were worth they yet found time for a smoke and a joke and when we arrived it was more like a picnic than a battle.’ Grieve and the 4th Division men who had come up to the north of him were to go for the Oosttaverne Line.

THE FINAL PHASE of the battle plan didn’t go as easily as the first three. The advance on the Oosttaverne Line began at 3.10 pm. The allied gunners began dropping shells into their own infantry. Tanks came up to help the 4th Division in its attack. One can only wonder what these Australians thought, particularly when one broke down before the assault started. The last time they had been ‘helped’ by tanks was at First Bullecourt.

The Australians were attacking north and south of a road they called Huns’ Walk and came under machine-gun fire, some of it from pillboxes. The Hindenburg Line did not extend to the Messines–Ypres sector, but the German defences there were exceptionally deep and dotted with pillboxes, which were, in part, a response to waterlogged ground. Some had loopholes for machine guns; others were simply shelters. Squat and lumpy, they could survive just about anything other than a direct hit. The Germans in these concrete forts could fire away until their ammunition ran out, or until the allied troops got behind them. When grenades started coming through the loopholes the Germans usually wanted to surrender, and this was thought a little too neat. As Bean wrote: ‘When they [the Australians] have been racked with machine-gun fire, the routing out of enemy groups from behind several feet of concrete is almost inevitably the signal for a butchery at least of the first few who emerge, and sometimes even the helplessly wounded may not be spared. It is idle for the readers to cry shame upon such incidents, unless he cries out upon the whole system of war.’

Germans in a pillbox near Huns’ Walk were firing into 4th Division men. Lewis gunners fired into the loophole until the German gun fell silent. Private Wilfred Gallwey wrote in his diary that the Australians went to the door at the rear of the pillbox and found the gun crew huddled inside, some wounded, some dead. The Australians fired point-blank into the huddle. ‘There was a noise as though pigs were being killed. They squealed and made guttural noises which gave way to groans after which all was silent.’ The bodies were thrown in a heap outside and lay there for days.

Grieve came under fire from another pillbox. He lost half his men and all his officers. He decided to attack the pillbox alone with a bag of bombs. He would throw one, then dive into a shell hole, all the time working closer. He landed a bomb close to the loophole – he had been a good left-arm bowler with the Brighton cricket club – and the machine gunners ceased firing. This allowed him to rush forward and drop two grenades inside. Silence. Grieve went to the back door and found the crew lying dead or wounded.

The survivors of Grieve’s company went on to capture a large batch of prisoners. Then a sniper in a tree shot Grieve in the right shoulder. A Lewis gunner fired a whole magazine into the tree and the sniper ‘dropped like a stone’. Grieve kept pushing his men forward to the Oosttaverne Line, but he was losing too much blood and decided to walk back to the casualty-clearing station.

The 4th Division battalions on Grieve’s left also took heavy casualties as they approached the Oosttaverne Line. Bean described the Australians as ‘maddened’. The Germans were ‘panic-stricken’: they had the Australians in front of them and the British barrage crashing down behind them. Many quickly surrendered with cries of ‘Mercy!’ Some clutched at the Australians’ knees. The Australians came on a farmhouse flying a flag that said it was a German aid post. An Australian officer beckoned to the thirty Germans inside to come out. As they did so, the officer was shot through the shoulder. The Australians behind him closed in, thinking the shot had come from the farmhouse. The officer, though in pain, stopped them shooting thirty unwounded Germans.

By darkness Plumer’s troops had taken the Oosttaverne Line except for two small sections, one on the British front to the north and another where the Anzac line joined that of the British corps above it. No British attack in the war had succeeded so well on the first day.

GRIEVE ARRIVED AT the casualty-clearing station. The staff was busy with cases that Grieve considered more serious than his, so he left and had something to eat with two stretcher-bearers he knew. He then went to battalion headquarters, explained what had happened at the front and made suggestions about the next day’s fighting. He walked another 1000 yards to a dressing station and had his shoulder bandaged. ‘I was covered in dirt and mud – my tunic saturated with blood so I must have presented a pretty picture. I was that tired that I could have laid down alongside the road and gone to sleep.’

Grieve was sent to hospital in England, spent some months there, then rejoined his battalion, only to fall ill and be invalided home. He married a nurse, May Bowman, who had looked after him during his illness. He won the Victoria Cross for his day at Messines.

HAIG WROTE UP his diary for the day:

Soon after 4 pm I visited General Plumer at his H. Qrs. at Cassel, and congratulated him on his success. The old man deserves the highest praise for he has patiently defended the Ypres Salient for two-and-a-half years, and he well knows that pressure has been brought to bear on me in order to remove him from the Command of Second Army … The operations today are probably the most successful I have yet undertaken.

Bean tried to write up his diary: ‘More c-attacks, I’m afraid. Too dead sleepy, what with gas & fatigue of this morning’s work, I can scarcely write sense – keep on dropping asleep.’

And there his notes ended.