The Menin Road

September came, the last three weeks of the fourth summer of the war that – despite what Haig was saying – seemed without end. Gough no longer made bold attacks, merely a niggle here and a parry there. These weeks were like a brief waking in a nightmare. The rain stopped, the sun rose in a golden orb each morning over Passchendaele Ridge and by noon the air was warm and balmy. Birds could be heard singing, hope amid the ruins. Here and there a blackened stump of a tree put out a single green leaf in a show of defiance. The ground mostly dried up and the sun baked a thin crust on it, so that wagon wheels sometimes produced puffs of dust. The shell holes still stank but the water in them had retreated to shallow puddles. The British soldiers who had fought in August knew this was all a tease; the newly arrived Australians didn’t think the place too bad. It was certainly good weather for flying. Soldiers on both sides stood and watched specks spitting at each other in the skies. Manfred von Richthofen was up there in his red Fokker; so too was Hermann Goering, a twenty-four-year-old who had grown up near Nuremberg, a city that one day would have another significance for him. Some Germans during the first week of September thought that the British had abandoned their offensive.

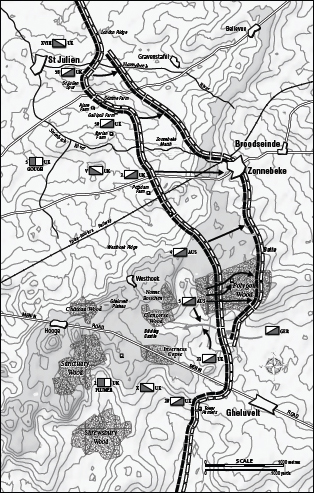

They were wrong: lack of resolution had never been one of Haig’s vices. Nevertheless the nature of his offensive had changed. By mid-September it was six weeks old. Like the Somme, it had started out as one thing and become another. It was no longer, in the first instance, about taking the Belgian ports. It was about taking the heights, the Gheluvelt Plateau, all 150 feet of it. It was not now so much about Gough, who would still command on the northern front, as about Plumer, who would be careful and limit his advances to a distance where his artillery could protect his infantry. Plumer didn’t see the Belgian ports or cavalry galloping through gaps, just the little ridges and pillboxes that had to be taken on either side of the Menin Road. He saw artillery ladder maps and just 1500 yards ahead: that was how far he intended to advance in a day, no more. Third Ypres now had the characteristics of a grinding match.

Two days before Plumer began what would be called the battle of the Menin Road, Bonar Law, the Conservative leader, wrote to Lloyd George, who was in Wales and unwell. Bonar Law said he had told Robertson that he [Bonar Law] had lost all hope of Haig’s offensive succeeding. He believed that Robertson agreed with him. Bonar Law felt that Haig could renew his attack any time. Therefore it was time for Cabinet to decide whether the offensive be allowed to continue.

PLUMER’S SCHEME, WHICH the Prime Minister and Bonar Law knew little of, was rather like his plan for Messines, except that he brought even more artillery to the battle. This time he had nearly 1300 guns for a frontage of just 5000 yards. Plumer came up with a creeping barrage that was particularly sophisticated. His forces would go for Nonne Boschen, Glencorse Wood and part of Polygon Wood on the north side of the road, and Inverness Copse and Tower Hamlets on the south side. Plumer would use two Australian divisions, the 1st and the 2nd, north of the road and three British divisions on the southern side. Gough would be attacking towards Gravenstafel at the same time with four divisions, but Plumer was the main player. Plumer’s attack would go in at 5.40 am on September 20. The preliminary bombardment began a week earlier. The fine weather continued. Then, just after dark on the night before the attack, drizzle began to fall, followed by heavier rain. The ground turned greasy and began to cut up. As one chronicler of the battle put it, Gough had become neurotic about rain, which at least proved he was learning something. He telephoned Plumer, wanting to call the assault off. Plumer hesitated and consulted. He decided to go ahead. Plumer was not only a better tactician than Gough; he was also luckier. The rain stopped just after midnight.

MAJOR FRED TUBB came from the congregation of the little Anglican church set beneath granite hills at Longwood in Victoria. He was relatively short, a little over five feet five inches, a farmer with strong expressive eyes and a neat moustache. He was a natural leader, an extrovert who loved sports – particularly football, horse-riding, foot-running and shooting – and every night wrote in a tiny diary. Lady Clementine Waring looked after him at her convalescent home in England in 1915 when he was recovering from the wounds he received at Lone Pine. ‘I can see him now,’ she said afterwards, ‘his whole personality radiating vitality and energy.’ When the award of the Victoria Cross was announced Tubb lost his ebullience. Lady Waring organised a reception. Tubb was confused and overwhelmed. ‘Finally in a broken voice,’ Lady Waring said, ‘he murmured a few incoherent words of thanks, and espying my small two-seater car nearby, leaped in with an imploring “For God’s sake get me out of this!” and whirled off through the gates.’

Tubb was invalided back to Australia early in 1916 because an appendicectomy had left him with an incision hernia. He eventually persuaded a military board to pass him fit to return to the 7th Battalion in France. His brother, Frank, was a captain in the same battalion. Menin Road was to be Fred’s first big battle after Lone Pine.

Tubb’s battalion was billeted in farmhouses around Bailleul, just over the border in French Flanders. Women, boys and old men were doing the ploughing and harvesting. The Australians helped one of the farmers bring in his wheat crop. Tubb’s hernia was obviously bothering him. He won his heat of a foot race at a sports day but wrote that ‘the race knocked me out’. The next day he was ‘unwell’ and on the following day he stayed in bed. He got up to go to Poperinghe to look over a model of the ground over which the Australians would attack above Menin Road.

The battalion left for the front on September 13. The night before Tubb wrote: ‘Am handing this [the tiny diary] to Frank tonight. I must not take it into the line with me. I hope to enter up my future doings on this when we come out.’

CAPTAIN A. M. MCGRIGOR, an English officer, was an aide-de-camp to Birdwood, whom he referred to in his diary, and with affection, as ‘the Little Man’. He liked the way Birdwood responded to the sensibilities of the Australians he commanded. McGrigor said that if the men were not wearing greatcoats at church parades in winter, Birdwood would also appear coatless. McGrigor, like Tubb, went to see the model of the battlefield at Poperinghe. It covered two to three acres, McGrigor said. The scale was one in fifty for the flat country but the ridges were exaggerated – ‘one could see clearly all the Bosche trenches, outposts and woods.’

The day before McGrigor had watched an Australian brigade practising an attack with a creeping barrage.

Very interesting it was too, but it did bring home to one how appallingly mechanical everything is now, and how every man must conform to and advance with the barrage. Initiation and dash must to a certain extent be fettered as every forward movement is worked out so carefully and mathematically and must not be exceeded or the objective fail to be reached, otherwise the effect of the carefully thought out barrage is lost and the attack is possibly beaten off or an entire failure.

McGrigor, in two sentences, had caught the essence of the new tactics that were evolving, though not yet generally accepted. They were ideas that had been born out of failures that had been called Loos and Fromelles, the first day of the Somme and First Bullecourt. Prior and Wilson contend in Passchendaele that McGrigor’s remarks highlight the difference between Gough’s opening offensive at Third Ypres and what Plumer was now trying to do above Menin Road and beyond. Gough had tried to advance 4000 yards on the first day, not because this was the effective range of his artillery but because he wanted to place his troops within striking distance of Passchendaele Ridge. Plumer, the authors say, had not set his eyes on some desired geographical objective. ‘He calculated the distance over which his artillery could provide a safe passage for his advancing infantry.’

Menin Road would be won or lost on the effectiveness of the artillery. Artillery would conquer and infantry would occupy.

THE ATTACK OF September 20 – Plumer in the south, Gough in the north – involved eleven divisions on a front of eight miles. The 1st and 2nd Australian divisions were roughly in the centre. Two Australian divisions were attacking side by side for the first time. They liked this and also the fact that they had a Scottish division on their immediate left. The Australians were assaulting a position different to anything they had tackled before. There were no formal lines of trenches, just outposts and pillboxes and machine-gun nests that went on and on without apparent pattern. But there was a pattern. The Germans here were happy enough to let the enemy enter their front positions; their true strong points were much further back. And between the lightly held front and these strong points the Germans could counter-attack a confused enemy. The British artillery barrage would thus not fall, as it had at Second Bullecourt and Pozières, as a line of shell-bursts parallel to the Australian jump-off positions. This time there had to be a storm of shellfire at least 1000-yards deep. The gunners had to try to obliterate everything. And of course they couldn’t. It would be impossible to score direct hits on every pillbox. Plumer had an artillery piece for every five yards of front; the ratio for Gough’s attack of July 31 had been one-to-six. Plumer would fire 3.5 million shells during the preliminary bombardment and throughout the first day. The Australians had never gone out behind such a ferocious barrage.

When the Australians arrived at the front the ridge looked dry and yellow and the broken walls of farmhouses stood up like headstones. Then, during the dark before the attack, the rains came and in an hour the clay first became greasy, then gummy and noisome. The Australians were to take their ground in three advances. The first would take them to the Red Line. They would pause there, then go on to the Blue Line. After waiting there for two hours they would go on to the final objective, the Green Line. This is where the counter-attacks were expected to come. Fresh battalions, Tubb’s 8th among them, would leapfrog through the lines to take and hold the final objective. Also marked down for the Green Line was the 17th Battalion. This contained three brothers, the Seabrooks, aged twenty-one to twenty-five, from the Sydney suburb of Five Dock.

Many of the Australians were wet from the waist down and carrying several pounds of mud on each boot as they assembled for the jump-off. Then a German barrage came down on half of the 1st Division. The casualties were severe. One battalion lost all its company commanders and half its officers. This was in the hour before the British barrage opened up at 5.40 am. The Australians set off, most of them lighting the cigarettes they had been denied in the assembly areas. Zero hour had been set at 5.40 because at this time it would be possible for the men to see 200 yards. The smoke from their own barrage meant they couldn’t see fifty yards. But it didn’t matter: mostly the Germans were too dazed and demoralised to resist strongly. Dozens of isolated fights broke out around pillboxes that had survived the barrage. These sometimes ended with Germans waving white handkerchiefs or bandages and trying to surrender and Australians wanting to kill them as they blundered out of the bunkers. The Australians usually had time to rifle through the bunkers for souvenirs before going on.

Joe Maxwell, a knockabout sergeant-major with a dry sense of humour, an ear for the vernacular and a taste for booze, set off with the 2nd Division. A shell fell behind Maxwell, knocking him down.

‘I crawled a few yards, scraped the mud from my eyes, and peered down into the terrified face of a German whose right arm hung a mangled red mass by his side.’ Through chattering teeth the German said ‘Kamerad’. Maxwell reached the German front positions.

And among that wilderness of broken timber and shattered concrete squirmed live Germans the colour of mud in which they wallowed – live men who had lost the power to think. Their eyes were glassy, and had lost all expression. They were sunk in faces that were ashen grey, drawn and paralysed by the terror of the storm that had burst over them. There they wandered without arms, mere husks of the men they were, for all practical purposes, men who were temporarily dead.

Maxwell received the Distinguished Conduct Medal for his part in Menin Road and was commissioned as a lieutenant. He had been fined twenty pounds for brawling in London. Fifteen pounds of this was now refunded and the DCM carried a grant of twenty pounds, so, as Maxwell put it, ‘I came out on the right side of the ledger.’

Private Walter Bradby of the 1st Division had enjoyed his four months away from the front, particularily when he downed his fourth glass of vin blanc at the estaminet that displayed a sign: ‘English spoken. Australian understood.’ Bradby was following the creeping barrage when a man about twenty-five yards ahead fell. He asked Bradby for a cigarette. Bradby recognised him as a man who had lived near him at Ballarat. Arch Sneddon had been hit in the back by shell fragments. Bradby said he seemed cheerful enough. Sneddon died at a dressing station.

Bradby saw British troops capture a pillbox on lower ground to his right. One German began pushing and jostling his captors. Two British troops bayoneted him. Up ahead Bradby could see a wood – almost certainly Polygon – ‘that seemed to have survived three cyclones and two tornadoes’. Bradby and half-a-dozen men reached their objective and started digging a trench. A small shell landed among them. Bradby and the others arose and began brushing earth from their eyes and ears. Bradby noticed that an older man named Malone – Bradby was only twenty and Malone looked to be thirty-five or older – was fumbling. He told Bradby he couldn’t see. A hand was passed to and fro in front of Malone’s open eyes. He didn’t blink. Then someone noticed a tiny hole in his left temple. Bradby was told to lead him to a dressing station.

They came on Paddy Morgan and other stretcher-bearers clustered around a stretcher on which a wounded Australian lay. Three German prisoners were standing docilely nearby. A fourth German stood apart.

It transpired that he could speak English, and Paddy was pleading with him, cajoling him, threatening him to take hold of the fourth arm of the stretcher – all to no avail. The German, standing at attention and drawing himself up to his full height, stated that as an officer he would not help to carry the stretcher. This went on for a while until Paddy, losing patience, took a few paces forward and, drawing a revolver (which he had no right to be carrying), shot the German officer.

Bradby deposited Malone at the dressing station. Months later he heard that Malone had recovered his sight.

Sergeant Percy Lay, whom we last met at Second Bullecourt, wrote in his diary that his battalion took hundreds of prisoners who never attempted to fight – ‘we could have got to Berlin as Fritz was absolutely disorganised … It was very amusing to see the way our chaps went into the battle. It looked more like a race meeting than a battle. A good few got caught by our own barrage by being too eager to get forward.’ Lay’s diary rather understated what he had done. His platoon commander had been hit during the assembly. Lay led the platoon on to the final objective. For this the drover from Ballan received the Distinguished Conduct Medal. It was his third decoration for bravery in just over a year. He was also made a lieutenant.

Captain Stanley Calderwood of the 2nd Division came upon a three-roomed pillbox flying a Red Cross flag and bristling with two machine guns. He wrote in his diary: ‘All the tenants received permanent eviction notices …’ He also recalled a redheaded sergeant rounding up prisoners and decorating himself with their watches and chains.

THE PILLBOXES HERE caused a series of brutal incidents. Troops from the 2nd Division rushed a line of concrete shelters. Some Germans inside wanted to surrender and others didn’t, a common point of confusion. One came out with his hands up. Another fired between the first man’s legs and wounded an Australian sergeant.

‘Get out of the way, sergeant,’ a Lewis gunner yelled. ‘I’ll see to the bastards.’ He fired three or four bursts into the entrance and killed or wounded most of those inside.

While the 1st Division was making for its first objective Lieutenant Ivon Murdoch (a brother of Keith) was passing a pillbox that he assumed the battalions in front of him had dealt with. A bomb suddenly went off at his feet. Murdoch told his men to fire at the loophole. Another lieutenant worked around to the entrance of the pillbox and took nine prisoners. Murdoch’s men were unaware these men had surrendered and shot them all.

Around the same time a machine gunner on the roof of a pillbox checked the advance of the 11th Battalion. The battalion was intermingled with the 10th, commanded by an eccentric Englishman, Lieutenant-Colonel Maurice Wilder-Neligan. He sent a lieutenant and his platoon to take the pillbox. The lieutenant was within a few yards of the pillbox when a German shot him in the head. Wilder-Neligan said the men ‘went mad’. Germans tried to surrender and Australians pelted them with bombs. Eventually they allowed a German officer and forty men to go to the rear. Wilder-Neligan was an unusual commander. While his men were resting – some of them puffing on German cigars – before going on to the final objective, they received the latest copies of two Fleet Street dailies, the Mail and the Mirror. Wilder-Neligan had arranged to have them brought up to the front.

Another group of 1st Division men were resting before going on to the final objective when they came under fire from a pillbox. Captain Fred Moore ran towards the pillbox to be shot and killed by a German, who, it was later said, had already surrendered. The Australians killed this German and others. Officers intervened and stopped them killing the whole garrison.

Lieutenant Donovan Joynt of the 8th Battalion told of what was probably the worst such incident for the day. He came on troops shooting at a loophole in the upper storey of a pillbox from which fire was coming. The Germans in the lower storey surrendered. The Australians relaxed as the Germans emerged. Then a shot from the upper storey killed an Australian. The Germans there were apparently unaware of the surrender of their comrades below. The Australians began bayoneting their prisoners. One went to bayonet a German, only to realise that, in his fury, he had forgotten to fix his bayonet to his rifle. The German begged for mercy. The Australian fixed his bayonet and killed him.

Bean wrote in the official history that such incidents are inevitable in war, which is true enough, and that ‘any blame for them lies with those who make wars, not with those who fight them’. Perhaps. One also thinks of a line from Frederic Manning, an Australian who served with an English regiment. In The Middle Parts of Fortune, one of the most stylish pieces of writing to come out of the Great War, Manning wrote: ‘A man might rave against war; but war, from among its myriad faces, could always turn towards him one, which was his own.’

BEFORE LEAVING FOR the front Fred Tubb told the senior men in his company that Menin Road would be his last battle. There is nothing to suggest he had a premonition of death; more likely he had realised that he could not go on soldiering with a hernia.

Tubb took his company through to its final objective and seized a cluster of nine pillboxes south of Polygon Wood. These should have been 250 yards short of the British barrage, but shells began falling on Tubb’s men. Tubb hastily wrote out a field message saying that the barrage was falling short.

What happened next is not clear. One story has Tubb the extrovert dancing with delight on top of a pillbox, where he was wounded by a sniper’s bullet. While being carried off on a stretcher he was wounded again by a shell-burst. The casualty form says he was ‘dead on admission’. The cause of death was ‘G.S.W. [gunshot wound] Back penetrating abdomen’.

All three Seabrook brothers died at Menin Road. All had enlisted in August, 1916, two of them on the same day. William (known as Keith), a lieutenant and the youngest at twenty-one, lingered until the next day. He appears to have been hit while moving up to the assembly positions. His batman, who did not go up with him, said Keith was pale and anxious before leaving for the firing line but his handshake was spontaneous and affectionate. The other two brothers were both privates, Theo, twenty-four, and George, twenty-five. They died during the attack. Several eyewitnesses told the Red Cross the same shell killed both brothers. These accounts, however, are scrappy and inconclusive. The bodies of Theo and George were lost, although one of them may have been buried where he fell.

Private William Tooney, a thirty-seven-year-old railway worker from the Sydney suburb of Redfern, was particularly annoyed about being wounded at Menin Road. He had been hit in the right leg. He had to crawl to the dressing station because the stretcher-bearers had been killed or wounded. A few months earlier he had been wounded in the same leg at Bullecourt and spent twelve weeks in hospital. But he had larger concerns. His wife had died after he left for France and their two small children were with relatives. Lying in a London hospital and watching the ‘cruel’ German air raids, he longed for fresh photographs of his children. He wrote to his daughter, Edna, after she had sent him a postcard. The card showed ‘you are thinking of poor daddy, and I want you to think of your mother too although she is dead … all I want now is for the war to finish, when I can come home to you & Bim [his nickname for his son, William] and look after you both.’ Tooney did come home late in 1918, discharged as medically unfit. He died less than a year later from mustard gas poisoning.

Major Donald Coutts, a doctor with the 2nd Division, came up to the front the night before the attack. He had to dodge German shells on the way to his aid post, a tiny concrete structure only five-feet high. Outside stood a small sandbagged shelter for dressing the wounded. Coutts said the stretcher-bearers were demoralised by the shelling and the mud. ‘Some of them didn’t seem to understand when you spoke to them.’ His first casualty was a self-inflicted wound: the man had all but blown off his right hand.

Captain McGrigor, Birdwood’s aide, went to a hospital after the Menin Road battle.

One Australian whom the General spoke to, hit in both legs, the shoulder and the head, was as cheery as though nothing was the matter with him. It was an extraordinary and sad sight to see the fellows lying there, our fellows and Bosches side by side waiting to have their wounds dressed, no discrimination being shown between friend and foe. Went into the operating theatre where six men were being operated on at once, poor devils.

BEAN IN THE official history called Menin Road a ‘complete success’, better than Messines. In one sense Menin Road was something to celebrate. Plumer had advanced his army an average of 1250 yards. The planning had been thorough. The artillery diagrams were starting to look like the doodles of Albert Einstein, who, incidentally, was writing new theories of physics at Berlin University and saw the war as a form of insanity. The barrages had been tremendous, even if some of the counter-battery work had failed. The standing barrage prevented the usual counter-attacks and befuddled the Germans. The infantrymen mostly reached their objectives on time. Communications had not broken down; the generals never lost control. Plumer looked impressive; so did his tactics.

In another sense Menin Road played into the hands of Lloyd George and other doubters. The British generals didn’t seem to realise that the casualties were frightful for the amount of ground gained. Haig was wearing out his own troops faster than he was wearing out the Germans. If Plumer’s tactics were the right ones, then the price of victory was going to be outrageous. The 20,000-plus casualties at Menin Road bought a gain of about five-and-a-half square miles.

This was more than double the ratio of casualties to ground gained on July 31, the first day of Gough’s offensive that quickly bogged down in the mud. German losses at Menin Road were thought to be about the same as Plumer’s, or slightly less.

The Anzac push in the centre had succeeded better than any Australian attack so far in the war: it had literally gone by the clock, one step after another. But the Australians had still lost 5000 men dead or wounded. This was the equivalent of one-third of a division, or two months’ voluntary enlistments back in Australia. These losses had been incurred in roughly the same time span as the failed attack at Fromelles in 1916. And while Menin Road was a success, it was hardly going to win the war, or even open the way to the Belgian ports. This was the thought that seemed to be running around in Lloyd George’s mind.

HAIG SAW MENIN Road as a great victory. He doesn’t appear to have gone near the front since Third Ypres opened, yet he felt even more certain that German morale was breaking down. His confidence was up. He would now take all the Passchendaele Ridge, step by step. The next step would be Polygon Wood in a few days. After Menin Road, Lord Bertie, the British ambassador to France, wrote in his diary: ‘We have done a good offensive which is much appreciated. But will it lead to anything really important?’

This is how Lloyd George saw things. He didn’t believe the story that Haig and Charteris were pushing. He saw Third Ypres as another of Haig’s grinding matches, another unending list of casualties. On July 31 Haig was going to take the Belgian ports. Now, seven weeks later, Haig and the military trade union were selling an advance of 1250 yards on the outskirts of Ypres as a triumph. Lloyd George was still looking elsewhere – Italy, Mesopotamia, southern Turkey – and Robertson was wearing himself out trying to deflect him back to the western front.

Lloyd George went to see Haig in France around the time of Menin Road. He wrote afterwards: ‘I found there an atmosphere of unmistakable exaltation. It was not put on. Haig was not an actor.

He was radiant … the politicians had tried to thwart his purpose. His own commanders had timidly tried to deflect him from his great achievement. He magnanimously forgave us all.’

Haig and his staff told the Prime Minister how poor the German prisoners looked. This was proof that Germany was running out of good fighting men. Lloyd George said he would like to see some of these prisoners. The story goes that someone on Haig’s staff telephoned Gough’s headquarters and said all able-bodied Germans were to be removed from the cage. Lloyd George was driven to the 5th Army compound. He thought the German prisoners were a ‘weedy lot … deplorably inferior to the manly specimens I had seen in early stages of the War’.

Gough was sitting in his office at La Lovie Château. He looked out the window and saw the Prime Minister walking past with Charteris.

I was struck by the discourtesy of the Prime Minister in actually visiting the Headquarters of one of his Army Commanders and not coming in to him … It was an amazing attitude for a man in his position … He had never met me, and it would have been an opportunity of at least seeing for himself what manner of man I was, and of exchanging some ideas … It was in fact his duty to do so. I have since understood that he blamed me for this Ypres battle and for its long continuation … I merely received my orders from the Field Marshal … even so, the responsibility was not entirely his [Haig’s] – the Cabinet must certainly have known the situation also and consented to these operations.

If there is an arrogant tone to Gough’s prose, there is also some truth in what he was saying. Cabinet had consented. It had not exercised its right to call off the operation. Lloyd George should have talked to Gough. Here was the whole trouble. Lloyd George didn’t like the military brass and wanted as little to do with them as possible; the military brass didn’t like Lloyd George and patronised him.

The Prime Minister went home unconvinced that Third Ypres was achieving much. Haig and Plumer went on with planning the battle that would be called Polygon Wood.

CLAUDE AND COLETTE Durand, retired schoolteachers from Hendecourt, the little village within walking distance of the old Bullecourt battlefield, have driven north, past fields of hops and herds of sleek Friesians, to lay a wreath on an Australian grave in a small cemetery near Ypres. The family of the Australian soldier are all too old to fly across the world to visit the grave. They asked the Durands to lay the wreath for them. It was important that the soldier be remembered. The Great War is gone and past; and it is still with us.

Fred Tubb lies in the ground here at Lijssenthoek Military Cemetery near a pink rose bush; Keith Seabrook lies nearby. Staff Nurse N. Spindler of the Imperial Military Nursing Service is also buried here. She was twenty-six. The inscription on her headstone says: ‘A noble type of good heroic womanhood.’ This is one of the largest British graveyards, simply because it was close to four hospitals. Poplars, willows, pines, maples and oaks rise among the graves. More than 1100 Australians lie here. Behind the cemetery is the cutting for an old light railway line that ran towards Ypres, and beyond that a large farm shed where one can still read soldiers’ graffiti from the Great War. Once this area was alive with roistering soldiers, hospitals, huts, tents and horse lines. Now it slumbers in the summer sun. It is quiet, except for the birds. That is the predominant sound of these hundreds of cemeteries all over northern France and Belgium: birdsong. Men die in their hundreds of thousands, usually to the shrieking sounds of shells, and afterwards birds sing over their graves.

Captain Fred Moore, whose death led to the killing of German prisoners at a pillbox above Menin Road, lies in Menin Road South Military Cemetery. He was twenty-two. Nearby is the headstone of a twenty-three-year-old Englishman from the King’s Royal Rifle Corps. The inscription reads:

NO MORNING DAWNS

NO NIGHT BEGINS

BUT WHAT WE THINK OF YOU

OUR BOY.

Gough was attacking in front of Langemarck at the same time as the Australians fought the battle of Menin Road. Langemarck has a German cemetery that assaults the senses, simply because it is so different. The British and French cemeteries have a pastoral elegance. They are sad places – they cannot be otherwise – but the light shines in and one is drawn to the cliché that these men are at peace, even if, in the case of the Anzacs and the Canadians, they are far from the sights and sounds of their youth. The German cemetery at Langemarck is Gothic and gloomy: it belongs to the forest rather than the plain, to the dark side of the heart. It speaks of pain and misery; it does not allow for redemption or peace of mind. Somehow it does not even allow for pity: it is working too hard at being spooky. The oaks are set so closely together that the light cannot shine in, even in summer. Birds do not sing here.

Many of the students, the carefree young volunteers of 1914 who died in ‘the Massacre of the Innocents’, lie in the mass grave that is the first thing you see as you enter the cemetery. Some 24,000 Germans are underneath, in a tomb that measures perhaps twenty-five yards by fifteen. Red begonias and rhododendrons frame the grave and beyond it is a trapdoor. Any bodies found on the nearby battlefields and identified as German go through this. At the far end of the cemetery stand the black statues of four men, just standing there, life-sized, ghosts in a forest who somehow seem to be saying that, here anyway, men still wander in purgatory.

A Belgian tells us that when he was fifteen he worked at Langemarck as a telegram boy. He says he always pedalled faster when he passed within sight of those four men, particularly if it was a grey day.

At Longwood, in north-eastern Victoria, the birdsongs are different, the music of magpies and the screeching of cockatoos. St Andrew’s Anglican Church, a token gesture to God in the Great Australian Nothingness, is a small white weatherboard with a corrugated iron roof and a lean-to at one end in which the priest can change, taking his white surplice from a hook and his Bible from a battered tin trunk. Outside a grey bell is mounted on an iron post; it still sounds every Sunday and seven or eight worshippers turn up. Inside the church is bright and friendly: white walls, a tiny organ, bar radiators on the walls, homemade cushions on white pews. The hard light from outside streams in through windows stained yellow and pink. The Tubb family once sat in the second and third rows on the left. Above these pews is a list of golden names on varnished wood: the Victoria Cross winners Tubb and Leslie Maygar, the Military Cross winners Frank Tubb and Gordon Maxfield, and dozens of other locals who went off to the Great War.

Across the highway is the Tubb family home, which was originally built as a hotel. It is two-storeyed, Georgian in style, European rather than Australian, so it’s probably right that Fred’s father, who was fascinated by Napoleon, called it St Helena, an island in a sea of yellow grass. Ten children were born in this house; the nearest doctor was at Seymour, twenty-five miles away.

Near the old Melbourne-to-Sydney road a small cairn rises out of the bleached grass, a simple column that honours the district’s three Victoria Cross winners (the third being Alex Burton of Euroa). This is where Fred Tubb farmed and where his nephew, also Fred Tubb, still farms. The Great War is gone and past, and it is still with us.