Bruchmüller’s orchestra

Winston Churchill, now Minister for Munitions but not quite forgiven for Gallipoli, happened to be in France when Operation Michael opened at 4.40 on the foggy morning of March 21. All his adult life Churchill had been a man of Bohemian habits. He napped when others worked. He worked at 1 am when others slept. If the ideas and words kept coming, he went on until dawn, sipping at brandy as his sentences, crisp and clean, marched into the night. On the night of March 20 he was staying with his old friend Henry Tudor, a divisional commander in Gough’s army, in the ruins of Nurlu, ten miles north of Péronne.

Churchill awakened a little after 4 am. He lay musing for perhaps half-an-hour. Then he heard Ludendorff’s 6600 guns, the heaviest barrage in the history of warfare.

… the silence was broken by six or seven very loud and very heavy explosions several miles away … And then, exactly as a pianist runs his hands across the keyboard from treble to bass, there rose in less than one minute the most tremendous cannonade I shall ever hear … through the chinks in the carefully papered window the flame of the bombardment lit like flickering firelight my tiny cabin.

Churchill went outside. ‘This is it,’ Tudor said. He had ordered all his batteries to open up. Churchill could see the frontline for miles.

It swept around us in a wide curve of red leaping flame stretching to the north far along the front of the Third Army, as well as of the Fifth Army on the south, and quite unending in either direction. There were still two hours to daylight, and the enormous explosions of the shells upon our trenches seemed almost to touch each other, with hardly an interval in space or time. Among the bursting shells there rose at intervals, but almost continually, the much larger flames of exploding magazines. The weight and intensity of the bombardment surpassed anything which anyone had ever known before.

Daylight came. Mushroom-headed clouds rose above exploding British dumps. At 10 am Churchill left for Péronne. Tudor held his frontline, then had to retreat when the divisions either side of him gave way.

HAIG WAS NOT a man of Bohemian habits. Bohemians were foreigners and not to be trusted. Haig’s life was built around order. Most of the time his daily timetable was as rigid as Field Service Regulations. At 8.25 each morning Haig’s bedroom door opened at his château outside Montreuil and he walked downstairs. In the hall he would stop in front of the barometer and tap it. He then walked for four minutes in the garden before returning for breakfast at exactly 8.30. At 9 he went to his study and worked for two to two-and-a-half hours. Lunch was at 1 pm. If he visited an army or corps headquarters by car, he would arrange for a groom to bring up his horse so that he could ride the last three or four miles back to the château. If he didn’t leave Montreuil for the day, he rode in the afternoon, accompanied by an escort from the 17th Lancers. On the return journey he would walk the last three miles back to the château. He would then bathe, do his physical exercises and change into slacks, working at his desk until dinner at 8 pm. He then returned to his room and worked until 10.45, when he always rang the bell for his private secretary, Sir Philip Sassoon. When Sassoon appeared Haig always said: ‘Philip – not in bed yet?’

Haig’s diary for March 21 begins: ‘Before 8 am General Lawrence came to my room while I was dressing to tell me that the German attack had begun.’ More than three hours after Churchill, Haig had discovered that the Germans had launched a massive assault. His staff must have known about the attack shortly after it began. They must have realised it was nothing less than a crisis. But no-one woke up ‘the Chief’.

Haig came to the event three hours late, and the rest of his diary entry suggests he never came close to understanding what had happened on the battlefield that day.

AUSTRALIAN CORPS HEADQUARTERS first heard of the German attack at 9.59 am. White was in charge. Birdwood was on leave in England; Monash, who would normally take over in Birdwood’s absence, was on leave on the Riviera and reading George Bernard Shaw. White was apparently told that GHQ considered the situation ‘satisfactory’, which squares with Haig’s diary entries. Communiqués published in Britain took the same line. Bean said the public realised only with difficulty that the great battle of the war had begun. What was happening became clear to English newspaper readers in the next few days when they recognised the names of villages. Weren’t they the villages ‘we’ had taken in 1916 and early 1917? Weren’t they well behind ‘our’ frontline?

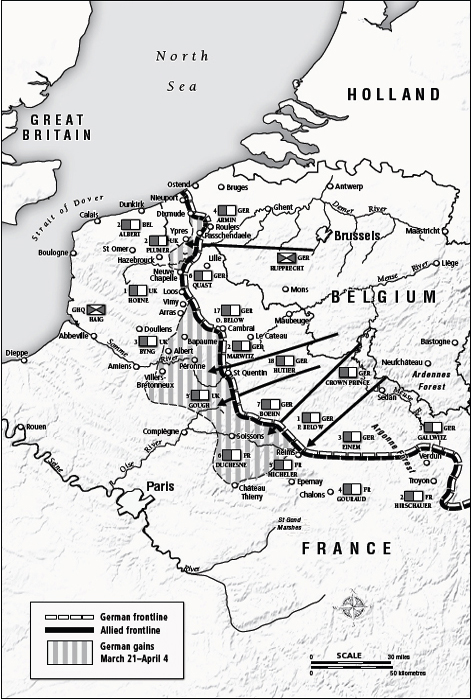

Birdwood returned by aircraft. This was thought adventurous: generals and politicians (with the exception of that irrepressible adventurer Churchill) invariably crossed by sea. Monash arrived back on March 25 after a thirty-two-hour journey. His division had first been told to move to Ypres, then ordered the other way, towards the Somme. Sinclair-MacLagan’s 4th Division was also sent south. The 5th Division was sent south to near Doullens, before marching to Corbie on the River Somme. All the Australians were talking about the electrifying news from the south. The Germans were within five miles of Pozières. Many Australians thought Pozières their cruellest battle. They could not conceive that the Germans might now take it back.

Bridadier-General Walter McNicoll, who commanded Monash’s 10th Brigade, called his officers around him before the move south and pulled out a map. According to a battalion historian, he told the officers that Gough’s army had been driven back and was retreating everywhere, that the British and French armies were in danger of being separated and that a long-range gun was shelling Paris. McNicoll told them that they would be in the battle of their lives ‘as the fate of the war now hung in the balance’.

GENERAL GOUGH CLEARLY didn’t think the fate of the war hung in the balance when he was awakened by the drumfire of artillery some time after 4.40 on the morning of March 21. He was at his headquarters at Nesle, about fifteen miles behind the front. He wrote afterwards that the barrage was ‘so sustained and steady that it at once gave me the impression of some crushing, smashing power’. Gough was told that his entire front was being hit. That was the serious part: the whole front. It meant he could not move divisions from quiet spots to places where the Germans were threatening to break through. There were no quiet spots and all his reserves were forward.

What did Gough do? He went back to sleep for another hour, arose, had breakfast, then began to deal with the worst crisis of his military life. Four days earlier, when just about every private in his army knew the Germans were about to attack, Gough had taken the Sunday off and ridden one of his horses to victory in a showjumping competition.

There were two reserve divisions under Haig’s control behind Gough’s front. Gough rang GHQ and was immediately given them. He spoke to General Davidson, the head of the Operations Section. The possibility is that Gough did not talk directly to Haig at any time throughout the day or night. Haig seldom used the telephone himself. According to Charteris, his long-time chief of intelligence, Haig believed that ‘conversations were inaccurate and liable to be distorted over the telephone, and that the agency of a third person using the telephone on his behalf ensured greater care and accuracy’. This may have been a windy way of saying that the field-marshal was often inarticulate.

Gough told Davidson he needed more than two divisions. He wanted help from the two armies at the northern end of the line that were not being attacked. Davidson said five divisions were being sent south, but the first four would go to Byng. Gough could not expect any help from the north for three days. The implication was clear enough. GHQ had to protect the Channel ports; Gough was in the wrong place. That night Gough spoke to General Lawrence, Haig’s chief-of-staff. Gough wrote afterwards that Lawrence ‘did not seem to grasp the seriousness of the situation’ and thought the Germans ‘would not come on again the next day’.

BRUCHMÜ LLER HAD ARRANGED his barrage like the conductor of a huge orchestra. Instead of woodwinds, brass, percussion and strings, he had heavies, mortars, field guns and the German staple, the 5.9-inch howitzer; he had high explosive, shrapnel and gas, lots of gas: chlorine, phosgene, lachrymatory and mustard. Sometimes Bruchmüller played fortissimo and sometimes diminuendo, back and forth across the British line, from a front trench to a canteen in the back areas, and even as far as Péronne, more than ten miles behind the front. The gas shells exploded with a pop and the high explosive with a roar. The howitzers lifted off the front positions, then, just when the stunned Tommies thought they had received a respite, returned again. In the crescendo, the last five minutes before the German infantry began its advance, all the howitzers fired on the front trenches. It was a complex score and there were limits to what it could do. It was to last only five hours and was spread over a fifty-mile front. The one thing it did achieve was to cause confusion deep into the British lines, and the fog made everything worse. British infantrymen couldn’t see the units on their flanks and this sometimes led to panic. Telephone cables were soon cut, even though they had been buried six feet in the earth. Men didn’t know what was happening fifty yards from them.

A private who had been in a tent in the battle zone with sixteen others told Martin Middlebrook, author of The Kaiser’s Battle, that the men had difficulty getting dressed when the bombardment began. They grabbed at their trousers, then found that they had one leg in theirs and the other in someone else’s. Another private told Middlebrook that no-one could stand shelling for longer than three hours before going sleepy and numb. ‘The first to be affected were the young ones who’d just come out. They would go to one of the older ones – older in service, that is – and maybe even cuddle up to him and start crying. An old soldier could be a great comfort to a young one.’

The German infantry, mostly storm troops, crossed no-man’s land at 9.40 am and met little resistance. Except in the Flesquières Salient opposite Cambrai, which the Germans intended to pinch off rather than attack head on, the British front fell everywhere within an hour-and-a-half of the infantry assault. Here was something new in the Great War: an attack that was instantly successful on a front of fifty miles. And this one did not stall. The Germans surged on, leaving pockets of resistance here and there, and all the time causing confusion. They came out of the mist, spectres in dull grey that were suddenly on the flank of some battered British outpost then behind another one. The Germans put up partridges as they went forward.

The Germans followed their barrage and reached the British battle zone, the main defence, well before noon. Lieutenant-General Ivor Maxse’s corps put up a strong fight opposite St Quentin but in many places the battle zone had been completely overrun by late afternoon. The Germans had broken right through on the fronts of three of Byng’s divisions to the north. On Gough’s front they had burst through the battle zone in front of Péronne. The southern end of Gough’s line, which ended at the Oise River, was a disaster: the battle zone had been completely lost on the front of his four southernmost divisions. Some Germans paused for booty, food and alcohol first of all, and also boots and leather jerkins. A German artillery officer whose horse had been killed picked up an English thoroughbred that stood beside its dead rider.

British counter-attackers tried to go forward as wounded and unhinged comrades tried to fall back. Lieutenant-Colonel J. H. Dimmer commanded a battalion in one of Maxse’s divisions. Dimmer had won the Victoria Cross at Ypres in 1914. He had grown up in the old British army and was loath to abandon its traditions. He decided he would lead a counter-attack himself – mounted. A junior officer suggested Dimmer dismount once he came under German fire. Dimmer refused and rode on with his groom riding alongside him. The watching troops couldn’t believe what they were seeing: Don Quixote and his faithful servant tilting at machine guns. The Germans shot them down. Dimmer’s horse bolted back through the British lines.

Mostly, though, the British troops were retreating. Men worried that they had no support on their flanks and pulled back. A chain reaction began all along the front. Some of the forts on Gough’s front held on after they were surrounded. There were 168 men in the Manchester Hill redoubt, on a small hill on the St Quentin front, when the Germans surrounded it. The men were from a battalion that had originally been the 1st Manchester Pals. Their commander was Lieutenant-Colonel Wilfrith Elstob, a burly schoolmaster who had joined up as a private.

When the fog began to lift on March 21 the Manchesters could see Germans streaming past the fort, ignoring it. They were following their orders: keep going; leave the points of resistance to the troops following. Then the Manchesters saw British troops coming towards them in a column. They were prisoners from the battle zone.

The Germans attacked the fort at 3 pm. Elstob refused a call to surrender. Elstob told brigade headquarters the Germans were in the redoubt but the Manchesters would fight ‘to the last’. He began to throw grenades and was shot. His adjutant tried to pull Elstob back into the trench. The adjutant was shot too. Both died and the Manchesters soon after surrendered. Elstob received a posthumous Victoria Cross.

Most of the forts were overrun or surrendered; the few that held out surrendered the next day. There were so many surrenders. At the end of the day the Germans had bagged their biggest haul of British prisoners in the Great War, 21,000. Many were taken to St Quentin where they were marched around the square for photographs that would appear in the German press. Crown Prince Wilhelm, the commander on the southern front and the eldest of the Kaiser’s five sons, came forward to see the prisoners. ‘He spoke to us in good English,’ a British prisoner said, ‘and congratulated us on putting up such a good show and on our excellent rapid fire.’ The Crown Prince was pleased with himself. He was the lesser commander in Operation Michael but the biggest successes had come on his front, against the southern portion of Gough’s line.

Gough went around his four corps commanders in the afternoon. He then made a decision that was out of character: he ordered his southern divisions to pull back even further to a better defensive position. Haig approved the decision.

On the night of March 21 the two generals did not know the extent of the crisis that was upon them, although they were looking at it from different vantage points. Gough knew his army could be pushed back much further; he may have been worried that he could be separated from the French to his south. Haig knew Gough was in trouble but also that the Channel ports were not yet under threat. The Channel ports were more important than Gough.

It had been the heaviest day’s fighting ever on the western front. It was the day infantry tactics changed. The Germans had taken ninety-eight square miles: nineteen from Byng and nearly eighty from Gough. Included in this area were the ruins of forty-six villages. In the Somme battle of 1916 the British and French had also gained ninety-eight square miles – but it had taken them four-and-a-half months to do so and cost them around 600,000 casualties. And, because of Gough’s decision to pull his southern divisions back and Byng’s decision to abandon the Flesquières salient, the Germans were about to gain another forty square miles, another eleven villages, without any serious fighting.

There are no official figures for the first day’s casualties. Middlebrook estimates German losses at 10,851 dead, 28,778 wounded and 300 prisoners, a total of 39,929. And for the British: killed 7512, wounded 10,000, prisoners 21,000, a total of 38,512. These figures, though roughly equal in total, favoured the Germans. The British had lost 28,512 men as dead and prisoners. These men were out of the war. The comparable figure for the Germans was 11,151.

ERNST JUNGER HAD joined the German army straight from school. After the war he would write the best-selling memoir The Storm of Steel. On the first day of Operation Michael he was leading a company. He went forward into the fog, having first taken a long swig of whisky. He came upon a wounded British soldier. Junger pointed his revolver at the man’s temple. The man pulled a photograph of a woman and children from his breast pocket. Junger lowered his revolver. He could not kill a man in front of his family.