Stragglers and heroes

The spring grass was peeping through on the Somme, sappy and irrepressible, as if to say that whatever men and machines did, the earth abideth forever. The last days of March and the first days of April were strange times on the British front. Not since 1914 had the war been so errant, so confused. The era of trench stalemate, its certainties and rituals, had passed. The frontline now changed by the hour. In many places there was no such thing, just lines of outposts. In the morning they were here and in the evening they were there; they were hardly ever where the generals thought they were. Haig’s army had prided itself on its orderliness. In the last days of March many of the divisions that faced Ludendorff’s onslaught lived in chaos and listened to rumours.

Formations south of the river were hopelessly mixed up. Gough’s 5th Army – what was left of it – had become Rawlinson’s 4th Army. Enterprising officers would cobble up scratch ‘divisions’ from labour companies, lost infantrymen, railway workers, walking wounded, the odd American and passing cavalrymen carrying lances. The cavalrymen were full of boyish ardour: they hadn’t much been in the war before and it still seemed like an adventure. Among the infantrymen, who knew it wasn’t an adventure, straggling had become common. Confusion always breeds stragglers and few aspects of war are more confusing than a retreat.

The Australian divisions were on the move, tramping down the line that began at Hébuterne, north of Albert, and stretched south, through Dernancourt and Morlancourt, and on to Corbie, on the river, and then south again, to Villers-Bretonneux. Strange incidents were taking place. The townspeople of Villers-Bretonneux had left hurriedly, leaving much wine and champagne behind. The Australians who arrived there in the last days of March used the champagne to wash down their hot meal in the evening. Some may also have used it for shaving and washing. A British divisional general came upon Australians carrying lumpy sacks that, one assumes, were also clinking. Much like a housemaster at one of the better public schools, he slashed at them with his oak stick, causing red and white wine to cascade down the Australians’ backs. The Australians ‘resented’ this high-handedness. Several of their officers arrived in time to ease the tension.

Pompey Elliott had brought his brigade south to the pretty town of Corbie, on the Somme. Elliott had always done a nice line in high-handedness. The looting of French houses appalled him. When a British captain was caught with a mess cart loaded with champagne Elliott posted a written ultimatum. The next officer caught looting would be summarily hanged in the Corbie market square and his body left swinging there as a deterrent. Elliott had read too much about the Duke of Wellington’s campaign in Spain, but the looting stopped. Elliott was to wonder later in the year why he was passed over for a divisional command.

Sergeant Frank Wormald came to Corbie with a detachment of 5th Division’s artillery.

The French had got out. They left everything, the shops, the pubs, the farms … Hens, talk about hens for dinner. They were laid on for a while. Booze, talk about booze, you could get all the champagne you wanted … Our wagon lines was at Bonnay [two miles north of Corbie] … We’d send a wagon into Corbie every night for booze and tucker and all that sort of thing. Don’t think that we living on booze – we wasn’t. You can’t fight a war like that and have booze.

A group of cooks went into Corbie one night.

They took off their clothes and dressed up as gentlemen – claw-hammer coat, white shirts, spats and the bloody lot … then they got on to the champagne and they couldn’t find the place where they’d left their clothes again, so they had to come home – in this bell-topper hat, claw-hammer coat and dress suit. It was a bit funny dressed like that in the frontline.

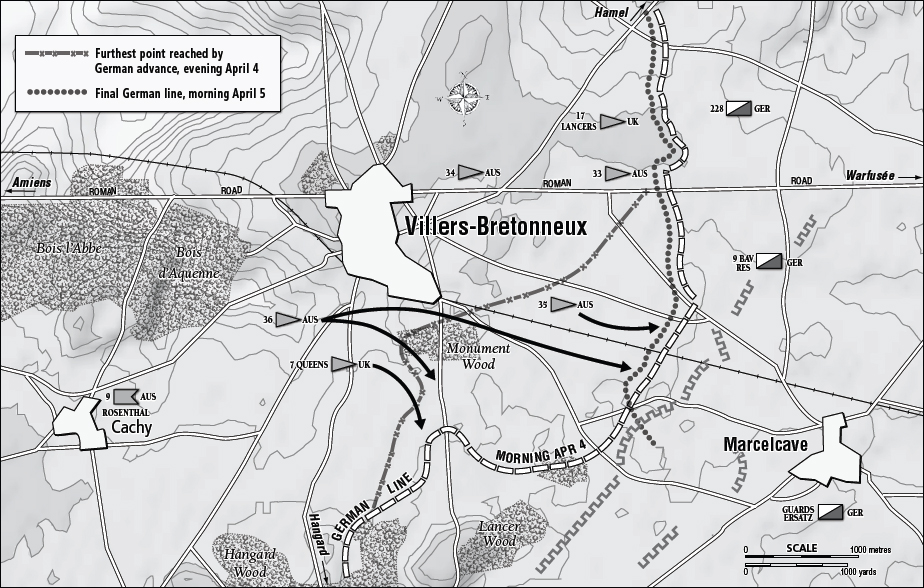

VILLERS-BRETONNEUX IN early April was just about the most important town in the war. It offered the Germans the best approach to Amiens. The town lay on a low plateau that looked down on the spire of the great cathedral at Amiens, ten miles away. A railway line and a Roman road both ran west to east through Villers-Bretonneux. About a mile north-east of the town the plateau rose to a point called Hill 104. From here one not only had a better view of Amiens but also to the lazy loops of the Somme to the north, to Corbie and Sailly le-Sec on the river itself and to the little village of Hamel to the east. Hill 104 would be the Germans’ best observation point. Even if they didn’t take Amiens, they could destroy its railway yards by artillery fire directed from here. South of Villers-Bretonneux a poplar-lined road led to the village of Hangard. Three woods rose out of the springing crops on the plain here: Monument (near a large farm of the same name), Hangard and Lancer. About three miles to the east lay the villages of Marcelcave and Aubercourt. The frontline in the last days of March was roughly halfway between these villages and Villers-Bretonneux. And it was to here that the Australians from Monash’s 3rd Division came on March 30.

The 9th Brigade, commanded by Charles Rosenthal, had been sent south the previous night and placed under the command of a British division. Rosenthal was a cavalier leader – he liked to be near the shooting – but the British general insisted that he place his headquarters well behind Villers-Bretonneux. Rosenthal’s four battalions were the 33rd, 34th, 35th and 36th. Leslie Morshead, a twenty-eight-year-old schoolteacher, commanded the 33rd. He was short, dapper and punctilious; it bothered him that rankers sometimes had the cheek to address officers while smoking. He was also a fine soldier; he had proved that from the moment he waded ashore on Gallipoli.

Rosenthal told Morshead he was to counter-attack to the east, towards Marcelcave and Aubercourt. Morshead was supposed to hold a front of 2700 yards with a battalion that, at around 500 men, was only at half strength anyway. And he was to have no artillery support. Morshead and his men set off across the open plain in drizzly rain that turned the red-brown soils greasy. A cavalry regiment, the 12th Lancers, came up to help on the northern flank. The cavalry and the Australians advanced south of Villers-Bretonneux towards Hangard and Lancer woods.

Morshead rode with the cavalry, pleased to be alongside a famous regiment. At Lancer Wood, Morshead wrote afterwards, he came upon British troops ‘uselessly entrenched in queer places, and large bodies of stragglers’. The troops were all pulling out, even though there was no hint of an attack. Morshead told the English officers he was about to launch a counter-attack and asked them to put their men back in the line. The British infantrymen turned around, but reluctantly. Stragglers were still leaving and no-one stopped them.

At 5 pm Morshead’s battalion, which was still back in Hangard Wood, began its attack. The men advanced quickly, despite the heavy ground, towards Aubercourt. The Germans could see them clearly and put up a heavy fire; there was no artillery barrage to keep them underground. The Australians fell thickly. Nowhere was the objective reached and the line, now down to about 300 men, was strung out over a mile.

A young cavalry officer who was with Morshead begged him to allow the Lancers to charge. ‘Oh, let’s have a go at them, sir,’ he said. Morshead admired the sentiment but said no. The cavalrymen, as was their custom, pulled out at dark. Morshead thanked them warmly.

Rain was still falling. Rifles and Lewis guns became clogged and maps turned to pulp. At dawn Morshead’s troops were pulled out and replaced by British troops. The objective had not been reached but the Germans had been checked.

THE NEWLY ARRIVED Australians and cavalry were supposed to be reserved for counter-attacks like Morshead’s, but some of the British divisions were down to 2000 men. So now another of Rosenthal’s battalions, the 35th, was on the night on March 30 told to take over the whole sector of a British division, some 2800 yards, on the southern front at Villers-Bretonneux.

The Australians went out in the dark. Captain Gilbert Coghill led the right company, which was near the railway line. He came upon five junior British officers crouched in a dugout in the embankment. They said that their men were ‘out there’, pointing to the plain to the south-east, but Coghill’s men found no line of posts. The Australians had to dig in before dawn. Most had dropped their entrenching tools while trudging through the mud. They dug with their hands.

Coghill was still there four days later, on April 3, when German aircraft swooped low over the Australian frontline. The men sensed the Germans were about to attack. Coghill’s batman was a resourceful man who had scrounged well in Villers-Bretonneux. Next morning he had just served Coghill a breakfast of chicken and champagne when the Germans began shelling the frontline. The bombardment lasted an hour. Visibility was poor and light rain was falling. As the shell-smoke cleared the Australians saw grey figures up ahead. The Germans were going for Villers-Bretonneux. Richthofen and his ‘flying circus’ were in the air.

Coghill told his men they were not to fire until he raised his arm. He didn’t want the Germans to take cover. He stood on the embankment so that all his men could see him and repeated his order. ‘All right,’ said one of his lieutenants, ‘but Christ couldn’t make me stand up there.’ When the Germans were forty yards away Coghill raised his arm, in which he held a map-case. Straight away he was shot in the arm. The Germans broke under the fire of the Lewis guns. Their officers rounded them up and sent them forward again. Each time Coghill allowed the Germans to come close before opening fire.

The Germans turned south to attack the British troops on Coghill’s southern flank. After the first assault the 7th Buffs, a famous British regiment, began to retreat. Coghill ran across to them and promised covering fire from his Lewis guns if the Buffs would return. They did. Coghill ran the 500 yards back to his own position as machine-gun bullets played around him. When he was almost back to the Australian line he looked around. The Buffs had left again.

North of the Roman road, where the 35th Battalion’s other flank lay, a newly arrived British division broke. Now both Australian flanks were open. The northern end of the line began to fall back, then the centre. Coghill, at the southern end, tried to hold on. His men were now being shot at from behind. They pulled back gradually towards the support position, lest they be cut off. Coghill was hit again, this time in the knee. He waited until his company was in the support trenches before going to the aid post.

Morshead’s depleted 33rd Battalion was sent up to help the 35th. By 9.30 am the new Australian line was reasonably strong, but the British line to the north was being rolled back. The village of Hamel seemed likely to fall.

The British 14th Division held the line north of the Roman road, past Hamel and on to the Somme. The division had performed poorly on the first day of Operation Michael and its commander had been sacked. According to Haig’s diary, his successor ‘went off his head with the strain’. The division, under its third commander in a fortnight, now couldn’t hold the line north of the Roman road. Some of its troops seem to have simply fled. Men from Monash’s division on the river saw Germans creeping into Hamel. Monash wrote home: ‘These Tommy divisions are the absolute limit, and not worth the money it costs to put them into uniform … bad troops, bad staffs, bad commanders.’

Elliott was told that as soon as his brigade could be relieved it was to cross the river and help the cavalrymen who were doing what the 14th Division was supposed to be doing. One of Elliott’s officers was already south of the river. With the help of cavalrymen he rounded up about 500 British stragglers. Many were without rifles. They said they had been told to dump them.

At noon Hill 104, behind the front where the 14th Division had been routed and offering the best view of Amiens, was in danger of falling.

IN THE AFTERNOON the two remaining battalions of Rosenthal’s brigade, the 34th and the 36th, were thrown into the battle to hold Villers-Bretonneux. The 33rd and the 35th still held the frontline just south of the Roman road. The 35th was on the southern end of the line and many of the men were so tired they were starting to fall asleep. Then, about 4 pm, they saw the British line to the south of them retreating. And now the Australian line became a shambles. A lieutenant at the southern end ordered his men to fall back and form a defensive flank. The Australians to the north thought the whole battalion was pulling back and a rout began. Two officers tried to steady the troops and failed. They ended up standing in the line alone, watching the Germans advancing towards Villers-Bretonneux. Much of the 33rd Battalion to the north also fell back as part of the chain reaction.

Colonel Henry Goddard, the commander of the 35th Battalion, was also in charge of the 9th Brigade’s forward headquarters. His post was in Villers-Bretonneux. Around 5 pm he discovered that his two front battalions had fallen back in disorder. His headquarters was suddenly the most forward Australian position. Panic now broke out here as well. Goddard ordered the 36th Battalion, which was south of the town, to counter-attack.

AROUND 4 PM CHARLES Bean was walking towards Villers-Bretonneux in the drizzle with Hubert Wilkins, the polar explorer who had become an official photographer. British troops were straggling back towards them without rifles. The pair soon realised ‘that the whole countryside was retiring’.

A soldier asked them: ‘Which is the road to Amiens?’

Bean and Wilkins asked two youngsters why they were retreating. ‘Too many Germans,’ they replied.

Bean noted that the German artillery had lengthened its range. Shells were falling on the back areas behind him. ‘It seemed to me,’ Bean wrote in his diary, ‘that he knew he had a broken crowd in front of him, and was turning his guns on to their retreat.’

Bean and Wilkins came on their first Australian stragglers, men from the 35th and 33rd, half-a-mile west of Villers-Bretonneux. Unlike the British they had their rifles, but they were still stragglers. One said the Germans were probably in Villers-Bretonneux by now.

Bean and Wilkins turned north towards the Somme, about three miles away. Near Corbie they met Pompey Elliott and told him what they had seen ‘so that if Villers-Bretonneux were taken he would not be caught in the flank’. Bean wrote in his diary: ‘I thought Villers-Bretonneux had gone, though I didn’t say so.’

COLONEL JOHN MILNE ran much of the way to his 36th Battalion to arrange the counter-attack ordered by Goddard. His men were south of the town, near Monument Farm. Milne arrived breathless and began issuing orders. The battalion would counter-attack due east towards Monument Farm and the wood of the same name just past it. One company commander asked: ‘How far shall we go?’

‘Go ’till you’re stopped,’ Milne said. He walked along the lines of men shedding their overcoats and other gear they wouldn’t need in the counter-attack. ‘Goodbye, boys,’ said Milne. ‘It’s neck or nothing.’

The men set off at a jogtrot. Soon they saw Germans pouring out of Monument Wood. The Germans saw them and returned to the wood and opened fire. Some sheltered behind haystacks near the farm. The Australians fell thickly, particularly officers, but they began to push the Germans back. When it was over Milne’s men had advanced a mile at the northern end of their front and half-a-mile at the southern end.

As they began digging in a man arrived and told them to pull back. He was wearing an officer’s tunic and a private’s cap. The lance-corporal in charge had been warned by his superiors about German tricks. He asked the man for his papers. He had none, so the lance-corporal shot him dead. No evidence was ever found to suggest that the dead man was a German.

On the other side of the railway line a company of the 35th had also gone forward strongly. The captain in charge jumped into a shell hole occupied by three Germans. He hit one over the head with the man’s coal-scuttle helmet and strangled a second. The third German escaped. Further north again, Morshead’s 33rd Battalion was falling back in some disorder when the 17th Lancers cantered up. The Australians turned back towards the enemy. According to Morshead, the sight of the cavalrymen – all their panoply, the drawn sabres and lances – inspired the Australians.

Villers-Bretonneux had been saved, for now, but the Germans had edged closer and Rosenthal’s brigade had lost 665 men. The counter-attack by Milne’s 36th Battalion had made the difference. Rosenthal, frustrated at being forced to stay so far behind the fighting, came forward after hearing of the straggling. He reached the frontline in the dark and ordered it moved forward slightly to better ground. More Australians were coming: brigades from the 2nd and 5th divisions had begun to cross the Somme. Soon Australians would hold most of the front.

NEXT DAY, APRIL 5, Bean and Wilkins went to Villers-Bretonneux. ‘It was a shocking sight – every house seemed to have been hit,’ Bean said. At the villa that had been Goddard’s headquarters the roof of the dining room was all over the floor. The kitchen door had been blown forward, hitting Morshead on the back of the head. A fortnight later Morshead was in a cellar when gas shells landed. He was blinded for three weeks and in hospital for two months.

Also on April 5 the 4th Australian Division fought a fierce battle at Dernancourt, about ten miles north of Villers-Bretonneux and on the other side of the river. The Germans here were also going for Amiens. Two Australian brigades held off two-and-a-half German divisions. Ray Leane’s 48th Battalion again fought magnificently. The Germans buried two Australian bodies at one of the 48th Battalion’s posts. They marked them with rough crosses, on which they wrote with an indelible pencil: ‘Here lies a brave English warrior.’

A German war correspondent wrote after the battle that ‘the Australians and Canadians are much the best troops that the English have’.

LUDENDORFF’S OPERATION MICHAEL virtually ended the day after this first battle for Villers-Bretonneux. Some of the Germans had advanced forty miles; they were tired and it was becoming difficult to supply them. Ludendorff was cranky and looking for someone to blame. The Germans had made the biggest breakthrough since trench warfare began. In fifteen days they had captured more than 1000 square miles and some 75,000 British prisoners, panicked the governments in Paris and London and caused the sacking of Gough. And yet the offensive had to be judged a failure. Ludendorff had been trying to capture Arras as a prelude to driving the British to the sea. He had never come near to achieving these objectives. Once the battle had begun he had settled on capturing Amiens and separating the British and French armies. He had failed here too, on the plain just east of Villers-Bretonneux. Instead he had managed to unite the British and French armies under Foch. He had broken Gough’s 5th Army but not Byng’s 3rd. He had captured dozens of towns and villages, yet none had strategic or symbolic value. Bapaume and Albert were not the same as Ypres and Arras.

Some of Ludendorff’s tactics – Bruchmüller’s barrages, the ever-moving storm troops – were inspired, but, as Correlli Barnett wrote in The Swordbearers, battles are not displays of virtuosity. ‘They are the means to the end of strategy, and Michael was therefore a titanic failure.’

And there was the matter of casualties. The British and French had lost about 240,000 men, the Germans at least 250,000. The grotesque arithmetic here went like this: the allies had a supply of replacements – more than 120,000 Americans were arriving each month – and the Germans did not. Yet Ludendorff was a gambler: another throw might do it. He decided to attack the British again, this time in Flanders.