‘Into the bastards, boys’

Anzac troops by early April held most of the Somme front. In the north the 4th Brigade of the 4th Division and the New Zealanders were at Hébuterne. Below them two brigades of the 2nd Division held the front south of Albert. Further south two brigades of Monash’s 3rd Division held the line to Corbie on the Somme. Two brigades of the 5th Division, including that of Pompey Elliott, had crossed the river and were spread out south towards Villers-Bretonneux. Other Australian brigades were in Villers-Bretonneux and south of it.

Foch and Haig were worried about the small German salient that poked into the allied line at Hangard Wood, about two miles south of Villers-Bretonneux. The line needed to be straightened and this looked easy enough on a staff officer’s map. The 5th Brigade from the 2nd Division was given the task.

We last met Captain Clarence Wallach at Pozières in 1916, where he won the Military Cross after being in charge of Blancmange Trench, so named because, as a result of German shelling, it changed shape every time he visited it. He was to lead one of the attacking companies at Hangard Wood. Wallach came from Bondi, New South Wales. Five of his brothers had also enlisted. All had attended Sydney Grammar. One brother, Neville, had been twice wounded. He too was a captain and had won the Military Cross. Clarence was tall with long legs, an open face and strong blue eyes. He had played rugby for Eastern Suburbs and for Australia in 1913–14. On Gallipoli he wrote a diary notable for its matter-of-fact style. Hardly anything bothered him. ‘Nothing of note, two skittled by shrapnel’ was a typical entry.

Lieutenant Percy Storkey, a twenty-six-year-old law student, was Wallach’s second-in-command at Hangard. He had migrated from New Zealand to Sydney in 1911 after being dux of Napier High School. Storkey had already been twice wounded. The attack, supported by a barrage, was to go in at 4.55 am on April 7. Rain had fallen in the evening and the night was cold. Storkey fell asleep. He awakened to find that the attack had begun. The rest of the company, including Wallach, was seventy-five yards ahead of him. This lapse may have saved his life.

Something had gone wrong on Wallach’s front. No barrage came down on the Germans ahead of him. Wallach waited a minute in hope, then set off across the 400 yards of open country towards the wood. German machine gunners, untouched by shells, opened up. By the time the company reached the edge of the wood one man in four had been hit. Wallach fell with wounds to both knees. Storkey took command.

He pushed into the undergrowth with eleven men, trying to get behind the German machine guns he could hear chattering on his right. The Australians came to a clearing. There, with their backs to them and only twenty yards away, were close to 100 Germans firing at Wallach’s company out on the open plain.

One of Storkey’s party yelled. The Germans looked around. Storkey shouted as if he had a battalion behind him. The Australians charged. The Germans in the nearest trench raised their hands. Those behind hesitated. They could have quickly turned a machine gun on its tripod and wiped out the dozen Australians. But Storkey’s manner bothered them. What if there were hundreds of men behind him?

Storkey called on them to surrender. The Germans hesitated. Storkey shot three with his revolver, which then jammed. His men rolled grenades into the trenches then shied away to avoid the blasts. Thirty Germans died. The other fifty-three surrendered.

Storkey’s men pushed on towards the company’s objective, where they were supposed to dig in. But where? The scrub near the objective was so thick that a man entrenched there couldn’t see more than a few feet. And about 400 yards ahead Germans could be seen on higher ground. It was pointless to entrench in a valley with Germans above them. Someone had made an error in selecting the objective. Storkey ordered his men to return to the start line.

Storkey found his battalion commander and told him the objective was impossible to hold. Go back and hold it, he was told. Storkey said he hardly had any men left. He would not take them back. He would go himself, if ordered, but only after he had explained the impossibility of the objective to his brigadier. Storkey’s fifty-three prisoners appeared under escort on a nearby slope as the argument continued. According to Bean, this saved an ‘awkward situation’. Storkey eventually saw his brigadier. He was not ordered back.

Wallach had a compound fracture of his left leg. Gas gangrene had set in and doctors amputated the limb. Wallach’s temperature soared to 105 degrees. He was given a blood transfusion, a relatively new technique at the front, to try to save the other leg, but eventually it had to come off too. Wallach began to weaken: the shock was too great. He died on April 22, aged twenty-eight.

Neville, his brother, also a good rugby player, died a little over a week later at Villers-Bretonneux. A shell burst at his company headquarters, sending a splinter through his head as the officers were sitting down to tea. Neville was twenty-one. The men made a ‘beautiful cross’ from a piece of furniture and erected it over his grave. The family never received the effects of Clarence and Neville. The ship taking them back to Australia was torpedoed.

Storkey survived the war, resumed his law studies, and eventually became a judge. For his day at Hangard Wood he won the Victoria Cross.

WHILE CLARENCE WALLACH lay dying Captain Manfred von Richthofen, the man Ludendorff had said was worth three divisions, was hunting over the Somme in his Fokker triplane with other members of his ‘circus’. The Australian and British troops stared up at the dull-red planes. Here was another hint that the Germans were going to try for Amiens again. There had been stronger signs.

On April 16 and 17 the Germans had sent over tens of thousands of gas shells on the Villers-Bretonneux front: mustard, ‘sneezing gas’ and phosgene. The Australians had pulled on their masks but the gas still got to them. Thin-skin areas, under the arms and around the crotch, became inflamed and the men’s eyes began to stream. The casualties ran to about 650. The shelling was obviously a prelude to an infantry attack. German guns were registering on the roads around Villers-Bretonneux. And the men on the ground kept seeing the red planes of Richthofen’s circus.

Rawlinson reorganised his front. The Australian Corps had been holding the line from Albert to the River Luce, a few miles south of Villers-Bretonneux. Now the Australian line would stop at Hill 104, on the northern side of the town. The British III Corps, under Lieutenant-General Richard Butler, formerly of Haig’s staff, would defend the town. The 8th Division, heavy with inexperienced reinforcements, took over the ground in front of Villers-Bretonneux.

POMPEY ELLIOTT’S 15TH Brigade had been holding part of the front north of the town. It was now in reserve. Elliott was convinced the Germans would go for Villers-Bretonneux again; he wasn’t impressed that British troops had taken over its defence. He had briefly lived in ‘a most glorious house’ near Corbie. It had a billiards room, a rare collection of butterflies, exquisite furniture, a conservatory and a Cootamundra wattle in bloom. Elliott got about in a French car that had been abandoned. This was not ‘looting’: Elliott knew this because he wrote the rules about such things.

Elliott was full of bluster in these days. Haig’s headquarters had become concerned about rumour-mongering among British troops and the risk that this could lead to panic. GHQ said anyone spreading rumours was to be taken to the nearest commanding officer. Elliott issued an edict of his own. Anyone caught peddling rumours was to be treated as an enemy agent and court-martialled. If a battalion was in action and no satisfactory explanation was forthcoming from an accused man, he was to be summarily shot. Like Elliott’s threat of public hangings, the order was illegal and spoke to the infantile side of Elliott’s character. In other matters his judgement was better. He had been at the frontline almost continuously for three years. He knew a lot about this war. From what he had seen and heard he didn’t believe the British 8th Division could hold Villers-Bretonneux.

RICHTHOFEN AWOKE NEAR Cappy, a village below one of the southerly loops of the Somme, on the morning of April 21. He was happy. All his life he had enjoyed hunting and killing: boar, deer, elk, rabbits, bison, birds (including three pet ducks belonging to his grandmother) and, more recently, allied planes and their crews. He had made his eightieth ‘kill’ the day before. Toasts had been drunk. ‘Eighty – that is really a decent number,’ Richtohofen is supposed to have said. The German public lionised him: he was a superman from Nietzsche. He had shot down more planes than any pilot in the Great War. And in three days he was going on leave. He would shoot pigs in the Black Forest.

Richthofen was twenty-five and handsome in the style of a Prussian aristocrat: slim with finely chiselled features, blond hair and a cold stare. Each time he shot down a plane he ordered an inscribed silver cup from a jeweller in Berlin. He liked to display trophies, be they antlers or silver cups that represented men.

Richthofen breakfasted and stepped out into the cold east wind. A military band, sent over to celebrate the eightieth kill, was performing. Richthofen said the music was too loud and walked towards the hangars, stopping to play with a pup on the way. He climbed into his Fokker and flew west, along the Somme valley and towards the allied lines above Villers-Bretonneux.

On the same morning Captain Roy Brown, a Canadian flyer and a year younger than Richthofen, awoke about twenty miles to the west, near Bertangles Château, the headquarters of the Australian Corps. Brown had a stomach ailment; it was so bad he had been living on brandy and milk for a month. He was also worn out and unnerved by fourteen months of flying and killing. He should have been in a hospital. Instead he would fly his Sopwith Camel twice a day, then go to bed after dosing himself with brandy and milk. Brown had been credited with at least nine kills and awarded the Distinguished Service Cross. He was a modest man who did not keep trophies. Some of the kills had been awarded to him only because others had reported them.

Brown climbed out of bed and flew east. His squadron and Richthofen’s flying circus met near Cérisy, just below the Somme on the German side of the line. A dogfight began. It was a little before 11 am.

Richthofen, much like a lion that has spotted an antelope with a limp, chased an inexperienced Canadian pilot, Lieutenant Wilfred May, who lost altitude and scooted for home along the Somme valley. Roy Brown tried to save his comrade by chasing Richthofen and firing at him from behind and from the left before breaking off. May and Richthofen flew towards the Morlancourt Ridge on the northern bank of the river, where the Australians had set up antiaircraft batteries.

May zigzagged and flew low along the valley before easing his stick back to climb over the Morlancourt Ridge. Australian ground forces had opened up on Richthofen. Down in the valley Sergeant Cedric Popkin fired bursts from a Vickers machine gun. Up on the ridge two gunners, Bob Buie and Snowy Evans, blazed away with Lewis guns. Richthofen usually played percentages. He was breaking his own rules by flying low over enemy ground. The trophy had become everything.

May flew on for Bertangles. Richthofen suddenly banked to the right above the ridge. He turned towards the German lines, giving Popkin a second shot at him and at a closer range. Other Australians were also firing. Richthofen’s engine roared, as if to announce that something was wrong. The red Fokker rose abruptly, swung to the right, then sank like a game bird hit by shotgun pellets. It came down in a field above the valley, near the brickworks on the Bray–Corbie road.

The Australians rushed the plane. Richthofen was dead. A single bullet had hit him under the right armpit and come out near his left nipple. The bullet was lying loose in his clothing. Someone took it and it was never seen again. Sydney Leigh, a young Victorian transport driver, was driving along the road when he saw ‘the red aeroplane lying in a paddock’. Soldiers were swarming around it, taking souvenirs. Leigh acquired part of the propeller and it became a family heirloom.

Who killed the Red Baron? Roy Brown initially received the credit. Medical theorists have since said that a man with a chest wound similar to Richthofen’s would have had only about twenty seconds to live. If so, this rules out Brown, who had broken off the chase long before Richthofen’s plane turned and sank. The probability is that Richthofen was killed by ground fire.

The Red Baron was buried with military honours at Bertangles. Brown was said to be nauseated at the sight of Richthofen’s body. Australians fired volleys over the grave. Messages and photographs of the grave were dropped over the German lines the next day. Less than three months later the Richthofen squadron had a new commander. His name was Hermann Goering.

NO JOURNALIST AT the Great War was more conscientious than Charles Bean. He was at Villers-Bretonneux, now being held by the 8th Division. The 8th, Bean said, had been a good British division. What he now saw dismayed him. The scale of casualties the 8th had sustained had changed its character. During Operation Michael the division had lost nearly 5000 men, half its infantry strength, including 250 officers. England was now sending over eighteen-year-olds as reinforcements. Bean saw them arriving as Operation Michael ended. ‘For two days companies of infantry have been passing us on the roads – companies of children, English children; pink faced, round cheeked children, flushed under the weight of their unaccustomed packs, with their steel helmets on the back of their heads and the strap hanging loosely on their rounded baby chins.’ The 8th Division was now thick with these ‘children’. One may only wonder why General Rawlinson moved the more seasoned Australian troops out of the town.

The Germans began shelling the Villers-Bretonneux positions at 4.45 am on April 24. Many of the shells were mustard gas. It was not yet dawn and a mist was rolling in. The barrage was particularly heavy.

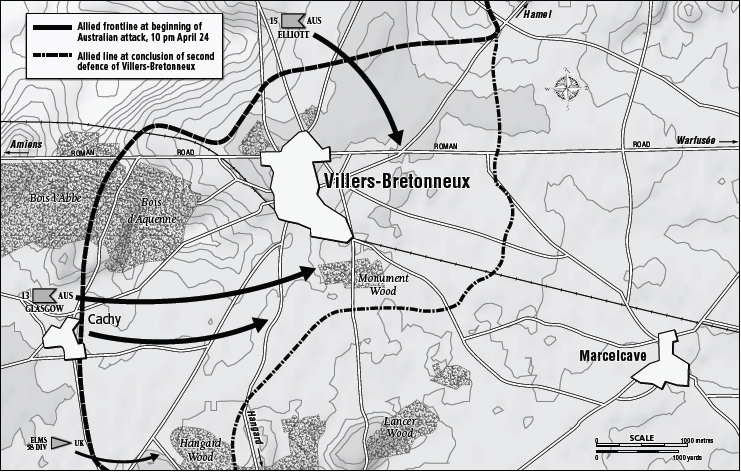

Pompey Elliott was at Blangy-Tronville, a few miles west of Villers-Bretonneux. He had for days been working on a plan of counter-attack and soon after the German barrage began he issued provisional orders for it. He did not yet have permission for the enveloping manoeuvre he had in mind; he didn’t even know what was happening at Villers-Bretonneux.

The British front positions were outposts rather than continuous trenches. The men who had survived the barrage could see less than 100 yards because of the mist and smoke. An English officer wrote that the German machine-gun fire seemed unusually accurate. When the fire ceased he peeped over the parapet and discovered why. An ‘enormous and terrifying iron pillbox’ was coming straight for him. The Germans were using a handful of tanks they had recently built and it is easy to understand the officer’s horror. These tanks were bigger, squarer and uglier than the British models, lumbering forts that carried a crew of eighteen. The English officer crouched as the tank, wheezing and heaving, passed over his trench. He then stood up and fired at the water jacket of one of its machine guns. That was the only thing he could see that looked vulnerable.

The tanks caused panic, more so because they came out of the mist. The British line broke and the Germans claim to have taken more than 2000 prisoners. The town fell. Foch, as generalissimo, told Rawlinson to get it back. Major-General Heneker, the commander of the 8th Division, tried several counter-attacks. None worked.

POMPEY ELLIOT WAS becoming cranky. He had a plan and he wanted to use it. The reports he was receiving were inconclusive but they all hinted at a German breakthrough. Australians holding the line near Hill 104 could see Germans emerging from Villers-Bretonneux and pushing north. Elliott rang Talbot Hobbs, his divisional commander. He had devised a counter-attack, he told Hobbs. Could he launch it? According to Elliott, Hobbs said yes. In truth Hobbs said much more. He said Elliott could only operate on the 8th Division’s front if he received an urgent request from the British to do so. Meanwhile he could move his brigade forward to bring it alongside the other Australians at Hill 104. And he had to keep Hobbs informed of whatever he was doing.

Elliott at once issued an order to his 59th and 60th battalions. They were to begin an enveloping movement on the northern side of Villers-Bretonneux. The order included this sentence. ‘All British troops to be rallied and re-formed, as our troops march through them, by selected officers, and on any hesitation to be shot.’ Here was another hint of megalomania, written down so that the world could see it. Elliott was close to his fortieth birthday and one step from command of a division; yet every now and then he behaved like a teenager who had become fevered from reading too much about Cromwell and Marlborough. A copy of the order went to Hobbs’ headquarters. Hobbs told Elliott to remove the sentence. Elliott couldn’t understand what he had done wrong, and still couldn’t a month later.

Hobbs had been trying to obtain information from Heneker, who had lost touch with his troops. Then Hobbs heard that Heneker was about to counter-attack. Hobbs told Elliott to wait. Small groups of British stragglers were arriving at the 15th Brigade’s lines. Elliott, mounted on Darkie, drew his revolver and threatened to shoot British gunners who wanted to pull back to the Somme. They decided to stay.

Noon passed. Heneker muddled, as did Butler, his corps commander. Elliott waited and, one suspects, swore a lot. Rawlinson, meanwhile, had ordered Glasgow’s 13th Brigade, on the Somme near Corbie, to march south eight miles and help with the recapture of Villers-Bretonneux. Heneker still seemed to be suggesting his own men could carry out the counter-attack. Rawlinson became more insistent that the town be retaken. He had now decided that the reinforcements in the 8th Division were children – his word – who had been shaken by their first bombardment. Heneker telephoned corps headquarters and said he couldn’t organise a counter-attack because ‘we don’t know where we are and where enemy is’. In truth he probably hadn’t known these things since early in the morning.

The generals talked through the afternoon and eventually came up with a scheme. There would be a night attack. Elliott’s brigade would attack on the northern side of the town, pushing east then turning south to the Roman road. Glasgow’s brigade would attack south of the town, then turn north to meet Elliott’s men and envelop the Germans. Two of Heneker’s battalions would then clear the town. Both Australian brigades would be loaned to Heneker. If this latter decision made little sense, it was the way things were done. Haig’s army was not a meritocracy; few armies ever are.

Glasgow was tough-minded and practical. He needed to know more about this night attack he was to make over ground he had not seen. He went to Heneker’s headquarters on the Somme flats. Glasgow wanted to work out a safe starting point, which meant he needed to know where the British troops were. Heneker pointed to spots west of Villers-Bretonneux. But he said the positions kept changing. ‘I can’t be sure of it,’ he admitted. Glasgow said he could easily find out where the troops were. ‘I’ll go up there myself and come back and see you.’ Glasgow went forward and satisfied himself that the British lines south-west of the village would hold. On the way back he saw his own men marching south, helmets cocked, cigarettes dangling.

A dispute now arose about where Glasgow should start his attack. Heneker said it had to start from the village of Cachy, because ‘the corps commander says the attack is to be made from Cachy’. Glasgow said he wanted it to start further north, between Cachy and Villers-Bretonneux. Heneker deferred to him. Glasgow said he wanted to start the attack at 10.30 pm. Heneker said it had to start at 8 pm, only a few minutes past sunset, because the corps commander ‘wished it done’ at that time. ‘If it was God Almighty who gave the order, we couldn’t do it in daylight,’ Glasgow said. Heneker referred the question to Butler, then successively asked Glasgow whether 8.30, 9 or 9.30 would suit him. Glasgow eventually conceded half-an-hour. The attack would go in at 10 pm.

Bean thought the night attacks would fail. Before going to sleep he wrote in his diary: ‘One cannot help thinking of our magnificent 13th Bde going over – as they may be doing now. I don’t believe they have a chance …’

Private David Whinfield, a stretcher-bearer in Elliott’s brigade, scribbled in his diary:

Such a day – I never want to see any more like it. Suspense specially deadly suspense like this has not one redeeming feature about it. Since 10 last night we have been rigged up all ready and to march off to support and now it is to counter attack for some ground lost by the Tommies this morning. We were moving off at 10 last night, 4 am, 9 am, 1 pm, 5 and now 7. It is a terrible time. How will men hang on at this awful cruelty. Nerves are being shredded. Men’s future strength is being heavily drawn from. My nerve is weak.

SERGEANT JIMMY DOWNING set off with one of Elliott’s battalions, the 57th. The 59th and 60th battalions were leading the northern attack, with Downing’s battalion following the 59th, which was on the right and closest to the town. ‘There were houses burning in the town, throwing a sinister light on the scene,’ Downing wrote. ‘It was past midnight. Men muttered: “It’s Anzac Day,” smiling to each other, enlivened by the omen.’

The men blundered into wire and took their bearings from the burning town on their right. A machine gun opened up ahead. A captain in the 59th Battalion gave the order to charge and a great swelling noise rose over the battlefield. All the men were yelling, shouting, howling, cheering. A shout went up: ‘Into the bastards, boys.’ The roar was so loud that Glasgow’s brigade heard it on the other side of the town. Downing said the men rushed straight at the machine-gun posts, rather than trying to take them in the flank. The Germans fought bravely, even continuing to fire machine guns when transfixed by bayonets.

The Australians ‘killed and killed’, Downing wrote. ‘Bayonets passed with ease through grey-clad bodies and were withdrawn with a sucking noise.’

Some found chances in the slaughter to light cigarettes, then continued the killing. Then, as they looked for more victims, there were cries of “There they go, there they go!” and over heaps of big dead Germans they sprang in pursuit … One saw running forms in the dark, and the flashes of rifles, then the evil pyre in the town flared and showed to their killers the white faces of Germans lurking in shell holes, or flinging away their arms and trying to escape, only to be stabbed or shot down as they ran … It was impossible to take prisoners. Men could not be spared to take them to the rear …

These are Downing’s recollections as published in 1920 in To the Last Ridge. He was more explicit in a letter written to a friend four days after the attack.

We made a long line and advanced. A petrol shell landed on an outlying building & set it aflame. We were seen. A tornado of machine-gun & rifle fire burst on the land. Some four men were smacked. That was the stark end of it. We all went fighting mad and did a thing almost unprecedented in war. There was a yell of rage and we charged – charged like hell hounds – like a pack of wolves … Then we were among them. We were Beserk, every one of us … There was no quarter. I remember bayoneting one Hun, a square fair solid fellow, and one old score was paid off. The bayonet passed right through his heart with surprising ease … One came to a machine-gun post which kept firing at us till we were on it & then surrendered. It was no use, this man said: ‘How many of you are there? Oh six. Then share that among you’ and he dropped a bomb among them. ‘Now you’ve got your issue’ … I saw Hun running away. I shot one dead. The rest disappeared in the gloom. The killing went on. I was mad. There was blood all over my rifle & bayonet & hands and all. Dawn broke & we started sniping & got many more Huns … We were sick of killing … We had avenged Fleurbaix [as the battle of Fromelles was then called]. I wouldn’t have missed it for anything. We settled many an old score. They were Prussian Guardsmen, too …

Downing dug in around dawn. He and the two companies of the 57th were near the Roman road east of the town. Two other companies of the 57th had been kept back as a flank guard. Now they pushed into the town. British troops were moving in from the west and Glasgow’s men from the south. Some of Elliott’s men arrived at a château on the edge of Villers-Bretonneux. They found a billiards table inside and began to play while bullets smacked through the window above their heads. They sniped back between shots. One man pounded out ragtime on a grand piano.

GLASGOW ATTACKED SOUTH of the town. There had been no time for a reconnaissance. Clouds blotted out the moon and the night became unusually black. The men had to reach Monument Wood, due east of their starting point, by 11 pm. The front formations were to push on speedily, leaving pockets of Germans to be mopped up by the second line. Billy Harburn, a captain in the 51st Battalion, told his men: ‘The Monument is your goal and nothing is to stop you getting there. Kill every bloody German you see, we don’t want any prisoners, and God bless you.’

His battalion, mostly West Australians, held the left flank of the attack and it was immediately in trouble. German machine gunners opened up from a wood to the left. Many of Harburn’s men fell; there was a risk that the attack here would be held up.

Lieutenant Clifford Sadlier, a twenty-five-year-old commercial traveller from Western Australia, commanded a platoon in Harburn’s company. Sergeant Charlie Stokes, a horse driver from Western Australia, was in the platoon next to Sadlier’s. Stokes crept up to Sadlier and asked him what he was going to do.

‘Carry out the order – go straight to our objective,’ Sadlier said.

‘You can’t do it,’ Stokes replied, ‘you’ll all be killed.’

‘Well, what can we do?’

‘Collect your bombers and go into the wood and bomb those guns out,’ said Stokes.

Sadlier decided to leave the line with his platoon, turn left and attack the wood. Sadlier and Stokes, who had grabbed a bag of bombs, led the rush, firing around bushes and trees. At the first machine-gun post they came upon a German who held up one hand in surrender and with the other shot Sadlier through the thigh. Sadlier shot him with a revolver, then kept going, dragging his leg.

The scene in the wood must have seemed Dantean: the Australians blundering in the dark, bright needles of tracer bullets streaming towards them, the crump of bombs, shouts and sighs, death and confusion. Sadlier attacked a post alone. He killed the crew of four with a revolver. He was wounded again and couldn’t go on. Stokes went from post to post and ran out of bombs. He met a corporal who had picked up some German stick-bombs. He used two of these to wipe out another German post, then went on and knocked out another two.

The crisis was over. All the posts – there were at least six of them – had been taken. The flank was safe. Sadlier and Stokes were both recommended for the Victoria Cross. Sadlier received it; Stokes was given the Distinguished Conduct Medal. It is hard to understand, on the known facts, how this distinction was made.

The line went forward again. Shots rang out in front. ‘Bomb the bastards,’ someone yelled. Bombs were thrown. The ‘bastards’ turned out to be remnants of two British battalions. They knew nothing about a counter-attack. They thought the Germans had got behind them.

Glasgow’s men next ran into a line of wire in their approach to Monument Wood. The German fire on the other side of the wire became heavier. A machine gun to the left was firing along the line of the wire. Sergeant Stokes eventually knocked out this gun too.

Before he had done so, the gun had left dozens of Australians dead or wounded on the wire. Captain Harburn and another company commander alongside him decided to blow their whistles and rush the wire. Many were hit as they tried to find gaps. German flares and the fires of Villers-Bretonneux lit up the battlefield. A corporal said it was just like daylight.

Those who got through the wire rushed the German machinegun posts. Harburn’s company, much depleted, came on a group of Germans who put up their hands. ‘No prisoners,’ said Harburn. Afterwards he said: ‘I did not know what to do with them.’

Glasgow’s men finished a mile short of their objective in places, which meant they were about 1500 yards behind Elliott’s brigade on the other side of the town, but they had done enough. They had pushed the German line back a mile. If the pincers had not quite closed, the Germans in the town were close to being cut off, especially since Elliott’s men held the Roman road leading east.

IN THE MISTY dawn two battalions from Heneker’s division and two companies from Elliott’s brigade began clearing the town and the wood behind, taking a large haul of prisoners. Next day the two Australian brigades finally linked up on the eastern side of the town, although Monument Wood still had not been taken. Glasgow’s brigade, which had been given the harder task, had incurred 1009 casualties. But for the bravery of Sadlier and Stokes, the figure would have been much higher. Elliott’s brigade lost 455 men.

The victory found many fathers. Haig said he ‘felt very pleased at the quiet methodical way’ General Butler arranged the counterattack. The war of movement had left Haig even more remote from what went on at the front. Birdwood came to congratulate Elliott. Elliott said that the general ‘really tried to be nice to me … but he rather looked as if I had made him swallow a bit of green apple. I wore my old Australian jacket and looked as disreputable as I could too. It’s a joke on these spick and span soldiers to show them that Australians have a few brains sometimes.’

Heneker didn’t bother to congratulate the two Australian brigadiers who had made him look better than he was. He was himself claiming credit for the operation. The headquarters of Butler’s III Corps announced in an official document that ‘the brilliant idea of the III Corps for the recapture of Villers-Bretonneux was ably carried out by the 8th Division, assisted by the 13th and 15th Australian Infantry Brigades’. According to Captain Ellis, the chronicler of the 5th Australian Division, the pomposity of this claim sent a flicker of amusement through the Australian brigades.

Elliott was furious with the British commanders: he felt that he should have been named as author. Here was another grievance he could carry for the rest of his life. The list was becoming rather long. Hobbs, the commander of the 5th Division, wrote in his diary:

Our people have had very trying experience with British people under whose control they have temporarily been. III Corps in an order issued claim credit for the admirable planning of the night operation … I really planned it, but I felt I should never get the credit of it. My experience of higher British command this last 4 weeks has not been very inspiring … and the conduct of some of the troops through the ignorance, neglect and I am almost tempted to say – but I won’t, I’ll say nervousness of their officers – has had a very depressing effect on me and I expect many of my officers and men.

Brigadier-General G. W. St G. Grogan commanded one of Heneker’s brigades at Villers-Bretonneux and a month later won the Victoria Cross. Writing in Reveille in 1936 he said: ‘[Villers-Bretonneux] will ever be remembered for perhaps the greatest individual feat of the war – the successful counter-attack by night across unknown and difficult ground, at a few hours notice, by the Australian soldier.’ Grogan had witnessed the start of Glasgow’s attack. He recalled that one Australian officer used very simple words: ‘Boys, you know what you have to do. Get on with it.’

PRIVATE WHINFIELD, THE stretcher-bearer who had written ‘My nerve is weak’ before the battle began, received the Military Medal for bravery. With typical modesty he doesn’t mention in his diary the incident that won him the decoration. Villers-Bretonneux didn’t leave him with the warm glow it bestowed on others. ‘I can’t rhapsodise over last night’s very successful counter-attack,’ he wrote on April 25, ‘others who feel different may.’ He had carried out wounded under shellfire – ‘a heavy strain on the nervous system’. And then things got worse.

Next day his diary entry began:

Harry Bramley killed. I’ve suffered a severe loss this morning my best friend who came over with me, been near and with me ever since got killed instantly at about 4 this morning. I was out with a wounded Fritz at the time. Such a straight goer, such a reliable fine man. And now he is gone from me. I feel for his people, for his May. I wonder why such good men suffer. This is the third of my best mates I’ve lately lost. Catto, Ryan and Harry. I am going to try to see him.

And he did. ‘Cliff Adams, Stan Newell, Jim O’Brien and I went and got Harry’s body and gave it a Christian burial in a cemetery on the road midway between Corbie and Villers-Bretonneux.’

A few days later Whinfield was out of the line. ‘No work or drill today. Had a bath the first for 8 weeks.’

Charlie Stokes had three children at the time of his exploit with Sadlier. A fourth, Gwen, was born after the war. Stokes was later to tell her that he had wept the morning after at Villers-Bretonneux when he saw what he had done to other human beings.

BUTLER AND HENEKER and their staff officers could cling to their delusions about what happened at Villers-Bretonneux; the presentday residents have no doubt about who recaptured their town. The school carries the words ‘N’oublions jamais L’Australie’ – ‘Never forget Australia’. The school stands on Rue de Victoria, which runs into Rue de Melbourne, and has a fine museum. Here is a photograph of Billy Hughes and Charles Bean together on the Somme in 1918. Bean looks fresh and clean cut in his captain’s uniform. Hughes is all hard bones covered with crinkly leather. You are reminded of a comment once made of him: ‘Too deaf to listen, too loud to ignore, too small to hit.’

On the northern outskirts of the town stand the ruins of a château, owned by a local factory-owner and destroyed by shellfire in 1918. Scars show on its red bricks. It must have been stately in its day; now it somehow seems magnificent, deserted and shot to pieces, but still standing and showing its wounds to the world. One wonders if this is the château where the Australians played billiards and ragtime. The position is right.

The Australian National Memorial stands high on a hill north of the town. From its tower you look over a patchwork quilt: the yellow of stubble, the green of sugar beet, the brown of fallow. Charolais cattle, sleek and heavy, graze in the summer sun and brown-red clouds swirl behind tractors scratching at the stubble. Through the haze one can just make out the spire of Amiens cathedral and, near it, a rival built long after the Great War, a grey industrial building that would have surely beckoned to King Kong. From this hill the Germans could have shelled Amiens to ash.

A few miles away, on the other side of the Somme, on the road from Corbie to Bray, near the old brickworks, corn is ready for harvest in the field where Richthofen died. The Morlancourt Ridge is on your left and the picture-book valley of the Somme on your right. There is no traffic on the road. All is quiet. And the place speaks to you. You can see a red triplane coming up the valley to the left of Hamel; you can hear the chatter of machine guns and the shouts of men on the ground. And then a car comes along the road to Bray and the triplane is gone.

THREE DAYS AFTER the counter-attack at Villers-Bretonneux a young man with a haunted face died of tuberculosis in a prison hospital in the Austrian town of Theresienstadt. He was Gavrilo Princip, the Bosnian Serb who as a nineteen-year-old had shot Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo. Princip was a nobody, a conspirator but no intellectual. Yet with two shots from a Browning revolver he had started perhaps the most terrible chain-reaction in history.

Dr Jan Levit, a military surgeon, attended Princip during his final days. Levit in 1942 found himself back at Theresienstadt – as a prisoner. Theresienstadt was now a concentration camp for Jews. Levit was sent to Auschwitz and killed. The author of the racial laws that deemed him unfit to live was in 1918 a corporal on the western front.