The press gang

Charles Bean first met Brudenell White in Melbourne in September, 1914, and liked him at once. White had fair hair, a high forehead, a Roman nose, pinky-white skin, twinkling blue eyes and two kind lines around a mouth that broke into a wide smile. Everyone remarked about the eyes and the smile: the eyes were piercing, the smile avuncular. White was a man of Victorian courtesy and charm. Even at thirty-seven he had an air of paternalism. He didn’t swear; he cared about manners and disapproved of showiness; he believed in duty and modesty. His handwriting was extraordinarily neat and he had a gift for clear English. He had an even better gift for organisation, sorting out problems with quiet persistence rather than bluster. He believed passionately in the British empire and its values. He was suspicious of democracy: to him it smacked too much of rule by the mob. ‘From his first word,’ Bean wrote, ‘I felt he was my friend.’ After Gallipoli the affection grew to something approaching idolatry. Bean saw White as a genius – his word – and perhaps also as the man he, Bean, would have liked to have been.

And now, on May 16, 1918, almost four years later, Birdwood had called Bean aside to tell him in confidence that Monash would shortly take command of the Australian Corps. Birdwood was leaving to command the 5th Army, which was being re-formed. He was taking White with him as his chief-of-staff, which made sense because White was good at the things Birdwood wasn’t, notably administration. Birdwood had in fact been holding two jobs: he was the field commander of the Australians on the western front; and he also had administrative control over all of the AIF, be it in Palestine, at AIF headquarters in Horseferry Road in London or the depots on Salisbury Plain. He was proposing to go to the 5th Army but also to retain the administrative post, General Officer Commanding (GOC) of the AIF.

Bean was so upset by what Birdwood told him that he appears to have fallen into a panic. Monash was a showman, too pushy, too ambitious, not Bean’s sort of chap – never had been. He was a ‘lucid thinker’ and a ‘wonderful organiser’ but he lacked ‘the physical audacity [whatever that meant] that Australian troops were thought to require in their leaders’. He might not be able to resist the callings of personal ambition. He might not stand up to an insistent superior or the strain of a disaster in the field. But it was the loss of White that bothered Bean most. White was ‘brilliant’ and ‘noble’, the obvious choice to command the Australian Corps. Bean not only believed all this was true: he thought many others in the AIF felt the same.

The next night he ‘blurted out’ the news to Will Dyson, the fine cartoonist who had become the official war artist, and Hubert Wilkins, the official photographer, at the Australian correspondents’ headquarters at Querrieu, near Amiens. Afterwards Bean wrote in his diary:

There was immediately a great consternation … We had been talking of the relative merits of White who does not advertise and Monash who does … Dyson’s tendencies are all towards White’s attitude – ‘Do your work well – if the world wants you it will see that it has you’ … Dyson thinks it a weakness, but he takes it better than the advertising strength which insists on thinking or insinuating itself into the front rank. He says: ‘Yes – Monash will get there – he must get there all the time on account of the qualities of his race; the Jew will always get there. I’m not sure that because of that very quality Monash is not more likely to help win this war than White, but the manner of winning it makes the victory in the long run scarcely worth the winning.’

This all seems strange. Did Dyson truly believe that winning the war was somehow shabby if a man he and his friends disliked happened to command the Australian Corps? And did Dyson really talk in such a stilted way in conversation with two friends?

The three decided that they would fight for White because they knew he would not fight for himself. They decided that Birdwood should go, that White should be given the field command and Monash the administrative post (which would possibly see him promoted to full general).

Bean cabled Senator George Pearce, the Defence Minister, in Melbourne, telling him that White, ‘universally considered greatest Australian soldier’, should not leave the corps. Then Bean and Dyson left for London to see Keith Murdoch. Murdoch knew about politics in a way they didn’t; he would know what to do.

ERIC EDGERTON OF the 2nd Division had seen some of Dyson’s sketches. He wrote in his diary early in 1918 that they were ‘very fine and typical of what the men actually look like in France’. Edgerton, big-framed and boyish, was in his third year of war and about to turn twenty-one. His life had moved at frantic speed since he had left Wesley College, Melbourne. He had enlisted as a student and risen from private to lieutenant; he had twice won the Military Medal for bravery; he had seen the horrors of Lone Pine and Pozières. Yet everyone spoke of his sunny nature. Now he was at the Amiens front, on the northern side of the Somme. ‘The villages around here are pitiful to see,’ he wrote just after his birthday. ‘If a few Australian towns were levelled in the same manner and the inhabitants had to leave all their possessions the general attitude of the Australian public to the war would alter …’

Edgerton was in action at Ville-sur-Ancre the day after Bean left to see Murdoch in London. He led five of his men into the village, rushed the German line, shot five Germans himself, then captured a machine-gun post. Edgerton had shown ‘brilliant leadership’, his battalion commander wrote in recommending him for the Victoria Cross. Edgerton received the Distinguished Service Order.

LUDENDORFF’S TWO BIG offensives had faltered and died. The cost on both sides had been terrible. British casualties for the forty-odd days after the opening of Operation Michael on March 21 came in at 236,300, nearly as high as for the Passchendaele offensive, which had lasted sixty-five days longer. The figure was worse than it looked: it included 70,000 men taken prisoner, which meant they were out of the war just as surely as the dead. The French had lost some 90,000, which brought the allied casualties to around 326,000. The Germans appear to have lost slightly more than this. And Germany, unlike the allies, was running out of men.

Yet Ludendorff and Hindenburg – in theory his superior – were still living with the delusion of total victory when they should have been thinking about how to negotiate a peace while they still held large tracts of France, Belgium and Russia. They were also delusional about conditions at home. More people were being drawn to Bolshevism. More were questioning the divine rights of Kaiser Wilhelm and asking where he was leading them. They didn’t know that he wasn’t leading them, that on most matters he had abdicated to Hindenburg and Ludendorff. Worst of all, Operation Michael had raised expectations at home; now it had petered out and so had the expectations. The war would go on without the prospect of a decision; children would grow up cold and hungry.

Robert Asprey wrote in The German High Command at War that Hindenburg and Ludendorff probably believed that the tide of defeat could be reversed.

Had they talked to ordinary people, perhaps they would have gained a more realistic notion of civil and military morale. They did not talk to ordinary people. They talked to people as pig-headed, blind, and greedy as themselves: industrialists, conservative politicians, bankers and economists who lied about production capabilities and fiscal soundness; to army group and army commanders and their chiefs of staff who lied about ground gained and enemy killed and the state or morale of their men; to navy admirals who had guaranteed that not one American soldier would land in France and who fatuously continued to claim that the crippled submarine offensive would any day force Britain from the war …

Ludendorff became more of a gambler. Now he came up with Plan Blucher. He would attack the French on the Chemin des Dames on May 27. The Germans surged across the Aisne and reached the Marne; soon they were only sixty-or-so miles from Paris, where the mood became panicky. Two American divisions were thrown in on the Marne and fought well. French troops retreating through an American position told a marine officer that his men should retreat too. ‘Retreat? Hell,’ said Captain Lloyd Williams, ‘we just got here.’

Ludendorff called off Blucher on June 3. Further gains there seemed improbable and his infantrymen had outrun their supply columns and artillery. Again, Ludendorff had taken large amounts of ground and caused affright. But, again, the blow was not decisive. And Ludendorff had lost another 100,000 men. It was not enough to say the allies had lost about the same number. The allies could replace their losses; Ludendorff couldn’t.

WHEN BEAN, DYSON and Murdoch met in London in mid-May they were trying for nothing less than to overturn a Cabinet decision. Birdwood had told Monash on May 12 that he had recommended him to the Australian Government for command of the corps. The only other contenders, Birdwood thought, were White and Hobbs, but Monash was the obvious first choice. Haig agreed with Birdwood. White, ever gracious, told Birdwood that Monash should have the job: he was an ‘abler man’. The Australian Government approved the recommendation on May 18 (the day Bean and Dyson travelled to London) in the absence of Billy Hughes, who was sailing to England via North America. Birdwood telephoned Monash and told him he had the job and promotion to lieutenant-general.

Monash’s chest swelled, as it was inclined to at such times. He wrote to Vic, his wife, that his corps was two-and-a-half times the size of the respective armies of Wellington and Napoleon at Waterloo. He had also worked out that his artillery was 100 times more powerful than Wellington’s. A few weeks later he mentioned that he was now driven about in a Rolls-Royce. By then he had moved into Bertangles Château, north of Amiens. It had an imposing façade of about 300 feet, Monash told Vic. Monash, as Birdwood later noted without rancour, liked to put all his goods on the counter.

Bean and Dyson apparently had to convince Murdoch that White should take over the corps. Bean says in the official history that the two of them swung Murdoch; in Two Men I Knew he says they persuaded him. After the meeting Murdoch cabled Hughes in the United States. Bean said that Murdoch’s cable exaggerated the intriguers’ case, then added that Murdoch was doubtless misled by himself (Bean) and Dyson, ‘who believed that their views represented those widely held in the AIF’. Murdoch’s cable claimed that White was ‘immensely superior in operations strategy and more likely inspire all divisions whereas Monash’s great ability certainly lies in administrative work’. Murdoch suggested the appointments be made ‘temporary’.

Hughes cabled Pearce in Melbourne urging that the appointments be held over until he reached London. Birdwood suddenly heard from the Army Council in London that his appointment to the 5th Army was temporary.

Murdoch, reverting to his other job as a journalist, tried to send a story to the Sydney Sun saying that there was a ‘strong unanimous view’ that Birdwood should not retain administrative command of the AIF, that White was likely to become corps commander and Monash GOC. The censor refused to pass the story.

THE DRAMA HAD now lurched towards farce. Consider, first, the behaviour of Hughes. He had twice divided Australia with campaigns for conscription. In doing so he had said, in effect: ‘Trust me. I know what is going on at the war.’ Yet he knew so little about what was going on that he relied on Murdoch to tell him who was fit to command the AIF. One might have expected the Prime Minister to have thoughts of his own on who should command his army.

Second, consider the position of Murdoch. He was playing courtier and journalist at the same time. Elected by no-one, apparently accountable to no-one, he was as powerful as anyone in the Cabinet in Melbourne. He had just managed, with one cable to Hughes and a word here and there around London, to have Birdwood’s new command changed to ‘temporary’. And he had his facts wrong.

There was no groundswell for White. It was misleading and, worse, an irrelevance, to claim that Monash lacked operational skills, and to imply that White possessed these qualities in larger measure. White had never held a field command during the war. Pompey Elliott was all about daring and dash, yet he was quick to realise that such qualities were not the most important credential for a corps commander in modern war. After the war Elliott would describe himself as an ‘efficient foreman’, a lawyer who instinctively looked to the past for enlightenment and precedents. Monash, the scientist and engineer, Elliott contended, had seen the future; he was ‘the designer of the new’.

Finally, consider the emotional journey that Bean was on. Everything he had done in the last few days was out of character. He had always been careful, as journalists should be, to be an observer rather than a player. He was a conscientious reporter, always checking to ensure that he had his facts right, no matter how minor the skirmish. And here he was, plotting and intriguing and counting numbers, not because he wanted to be a player but because he sincerely believed he was working to stop a ‘tragic mistake’. Bean thought all of the AIF adored White as he did. He likened him to Victor Trumper, the Australian batsman who had been called ‘the perfection of grace.’ In truth most Australian soldiers knew less about White than they did about Monash.

Monash was a modern man and this seemed to offend Bean. White, on the other hand, seemed to embody the values Bean had embraced as a public schoolboy in England. Monash had intellectual qualities – he was the true Renaissance man – that should have appealed to Bean, but they didn’t. Monash saw war as a vast engineering undertaking. Mastery of detail was more important than heroics. Realism was better than romanticism, clarity better than bluster. It was true that Monash didn’t get out among the frontline troops the way Birdwood did, and he probably should have done so more often, but ‘Birdie’ was a poor planner, and preparation was more important than gladhanding. What seems to have offended Bean most – and this is only apparent from reading his diaries and notes – was Monash’s vanity, his need to ‘advertise’ and seek the baubles of conventional success.

Colonel Thomas Dodds, Birdwood’s deputy adjutant general, ended up telling Bean he was an ‘irresponsible pressman’, which was sad because Bean was a man who put accuracy above all else. Bean, in turn, told Dodds that Monash had worked for Birdwood’s job ‘by all sorts of clever well hidden subterranean channels’. Bean decades later scribbled in the margin of his diary: ‘I do not now believe this to be true.’ The likelihood is that in later life Bean regretted his part in the plot.

Murdoch luxuriated in intrigues. Power interested him more than words. Manipulating people was his metier and he was good at it. Having cabled Hughes and caused confusion, he set about widening his front. Soon the dispute became even more confused. Was it, as Bean wanted it to be, about the respective merits of White and Monash as corps commander? Or was it about whether Birdwood should hold the job of administrative head of the AIF while also commanding the 5th Army? Everything now became muddled and nasty.

Birdwood realised what Murdoch was doing and wrote to Munro-Ferguson, the Governor-General, and other supporters. Murdoch, he said, was trying to be the ‘Australian Northcliffe’. Murdoch wrote to Monash to offer his ‘hearty congratulations’. Monash wrote to Vic, saying: ‘I profoundly distrust this man.’ Monash then wrote to Billy Hughes, suggesting he come to France and disputing Murdoch’s claim to be the spokesman of the AIF.

Bean wrote to White:

You know and I know and Gen. Birdwood knows and everyone knows, that our men are not so safe under Gen. Monash as under you. You know that no-one will safeguard them against a reckless waste – or useless waste – of life in impracticable or unnecessary stunts, or will get so much effect out of them in a good stunt – as you can or would.

Murdoch wrote to Monash again. Professor Geoffrey Serle, Monash’s biographer, called this letter an ‘explicit bribe’. Murdoch said that people had encouraged Monash ‘to regard me with suspicion and even with hostility, just as on occasions some have whispered and lied to me about you’. In fact he valued Monash’s ‘extraordinary ability’ and had always admired him as a soldier. ‘It takes two to make a friendship, of course, but please let me assure you that you have my personal esteem as one young Australian towards a much abler and wiser compatriot.’ Murdoch admitted he had recommended White for corps commander. He thought Monash’s ‘genius’ lay in the ‘higher sphere’ of administration and policy. The job of GOC was important. Monash might become a full general if he took it. Murdoch reminded Monash that his cables went to 250 newspapers.

Monash sent a diplomatic reply. Then he began to write to Birdwood about Murdoch. ‘It is a poor compliment, both for him to imagine that to dangle before me a prospect of promotion would induce me to change my declared views, and for him to disclose that he thinks I would be a suitable appointee to serve his ulterior ends.’ Monash didn’t send this letter.

Bean came to see Monash. Bean wrote in his diary afterwards:

Monash is a man of very ordinary ideals – lower than ordinary I should say. He cannot inspire this force with a high chivalrous patriotic spirit – with his people in charge it would be full of the desire to look and show well – that is the highest. There is no question where the interest of the Australian nation lies. It lies in making White one of its great men and makers.

Hughes arrived in London on June 15. He was the man both sides had to convince. Birdwood attended a reception for Hughes in London. The general was becoming unusually feisty. He had already written to Murdoch: ‘I dare say you will beat me, but, I warn you, I shall make a hard fight before I die.’ Andrew Fisher, the Australian High Commissioner, spoke disdainfully of Monash. Birdwood rebuked him. Murdoch asked Birdwood whether Monash really was fit to be corps commander. ‘Of course,’ Birdwood snapped, ‘he can do it much more ably than I.’ White wouldn’t accept the corps commander’s job if it were offered, Birdwood said. To do so would be to suggest that he had been intriguing with Murdoch. Birdwood told Hughes that he had complete confidence in Monash and that Rawlinson and Plumer also believed in him. Hobbs wrote to Pearce in Melbourne to say that the AIF respected Monash as a ‘fighting leader’. Bean wrote a note to Hughes setting out the case for White. Rawlinson said Murdoch was ‘a mischievous and persistent villain’. Bean wrote to White again. One has the feeling that Bean was embarrassing White. Monash told Vic that he had trumps to play. They were called Haig and Rawlinson.

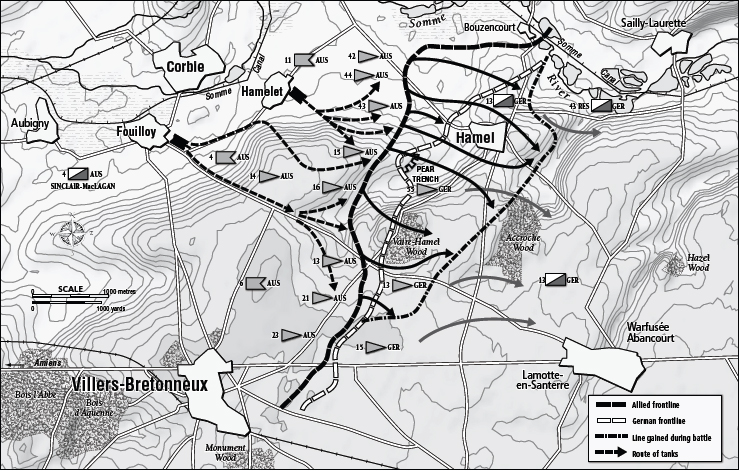

Hughes came to France on July 1 with Joseph Cook, the Deputy Prime Minister, and Murdoch. The timing was poor, although Hughes didn’t know this. Monash was planning a set-piece battle north-east of Villers-Bretonneux for three days hence. Hughes eventually told Monash that he wanted to postpone the questions of who should command what. Monash told Hughes that he would regard his removal as corps commander as a humiliation. He would not voluntarily give up the command. Hughes tried to soothe him.

Three Australian divisional commanders saw Hughes. All were for Monash. Hughes’ confusion grew; he became more crotchety than usual. He called Murdoch aside and told him he had met noone who agreed with his [Murdoch’s] views. Here was the pith of the matter. It had been there since May 16 when Bean, Dyson and Wilkins sat down at Querrieu. There had never been strong feeling against Monash; there had never been a push for White. Everything had proceeded from false premises.

White’s embarrassment grew. He wrote to Monash to say that ‘if the conspirators in this matter do happen to be General White’s friends, they are not acting at the suggestion or with the approval of General White’. White in mid-July rebuked Murdoch for impropriety and meddling. Murdoch took little notice: he didn’t take White as seriously as Bean.

Hughes eventually decided that Monash could have either job – corps commander or GOC. When it became apparent Monash wanted to stay with the troops, Hughes offered the GOC job as a full-time post to Birdwood, thinking he would be unwilling to resign his 5th Army command. It was now mid-August. Birdwood spoke to Haig, who told him to take the job but on the basis that he be loaned to the British army until November 30. This was apparently agreed to. The dispute was over. Nothing had changed. Monash commanded in the field; Birdwood retained the powers of GOC while also commanding the 5th Army.

JOHN GELLIBRAND, THE brigadier who in dress often looked scruffier than his men, in 1915 described Pompey Elliott as ‘gallant and despotic’. He also said he was ‘bull-headed and ultra-Victorian’. Gellibrand was now given command of Monash’s 3rd Division and Elliott was outraged.

The corps was being ‘Australianised’. Thomas Glasgow took over the 1st Division from the Englishman Hooky Walker. Nevill Smyth gave up the 2nd Division to ‘Rosie’ Rosenthal, the architect who sometimes walked up to twenty miles on his brigade front and had been three times wounded and once gassed. The Australian Corps was now a true citizens’ army, commanded by an engineer who also had degrees in law and arts and who entrusted his divisions to a Queensland grazier (Glasgow), two architects (Hobbs and Rosenthal), and a Tasmanian orchardist who had once served in the British army (Gellibrand). Sinclair-MacLagan, a career soldier born in Scotland, still commanded the 4th Division. He had first served in the Australian forces in 1901 and was apparently considered sufficiently ‘Australian’.

Elliott felt he had been superseded. He hadn’t: appointments to divisional commands were by selection, not seniority. Elliott had never been in contention, although he didn’t yet know this. He wrote to White, incensed that Gellibrand had been chosen ahead of him, and more so because Gellibrand was a ‘British officer’. Elliott hinted that he might appeal to Pearce, the Defence Minister. Elliott wrote in heat; White demolished him with cool prose. Gellibrand, White pointed out, was an Australian.

Then as to yourself why all this great assertion? Do you think anyone doubts your courage? No-one in the AIF, I assure you. Or yr ability? It is well known; but – you mar it by not keeping your judgement under complete control – your letter is absolute evidence. Finally you actually threaten me with political influence. You have obviously written hurriedly and I am not therefore going to regard yr letter as written. But let me say this: if the decision rested with me I should send you off to Australia without the least hesitation if calmly and deliberately you repeated yr assertion to seek political aid …

White saw Elliott and they argued. White said Elliott ‘suffered from lack of control of judgement’. He offered a string of examples, including Elliott’s threat to hang looters at Corbie. Elliott withdrew his letter but his anger grew. Ross McMullin, Elliott’s biographer, wrote that the ‘supersession’ was the greatest personal disappointment of Elliott’s life. The grievance never left him.

BEAN AND MURDOCH had failed in their intrigue. Bean admitted his errors and reported the affair at length in the official history. In Two Men I Knew he wrote: ‘So much for our high-intentioned but ill-judged intervention. That it resulted in no harm whatever was probably due to the magnanimity of both White and Monash.’ No harm whatever? While Monash was being undermined by Bean and Murdoch, while Billy Hughes was trying to discover things he should have known, the new commander of the Australian Corps had been trying to plan a battle for the little village of Le Hamel, three-and-half miles north-east of Villers-Bretonneux. Nine days before the battle was supposed to open Monash wrote to Vic: ‘It is a great nuisance to have to fight a pogrom of this nature in the midst of all one’s other anxieties.’ Geoffrey Serle wrote in John Monash that Australia’s higher commanders were distracted during some of the most vital days of the war. ‘It is perhaps the outstanding case of sheer irresponsibility by pressmen in Australian history.’