An American tragedy

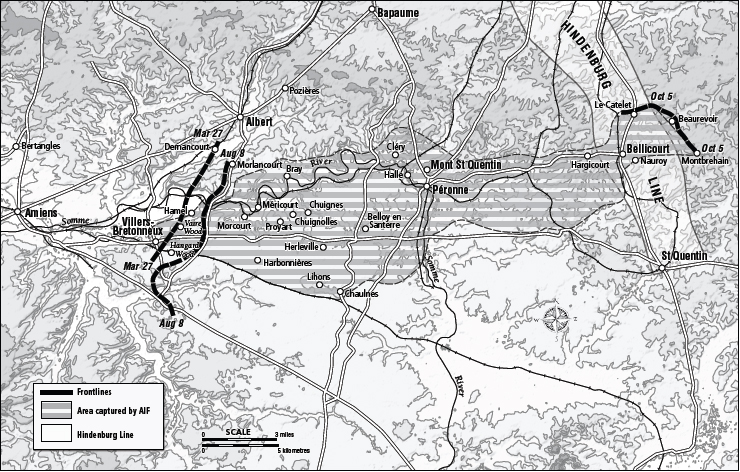

General Rawlinson didn’t much believe in General Richard Butler; he had no reason to. The advance eastwards of Butler’s III Corps, on the northern flank of the Australians, had been a series of stutters and failures, all the way from Villers-Bretonneux to the edge of the Hindenburg Line. Butler, a former deputy chief-of-staff to Haig, had been replaced temporarily after the Amiens battle. He appeared to have been suffering some form of nervous collapse. Now he was back. On September 16, two days before the attack on the Hindenburg outpost line, Rawlinson wrote in his diary: ‘I am pretty sure the Aust & IX Corps will do their jobs but am not so confident about the III Corps … If they make a mess of this show I shall have to talk seriously to Butler for it will be his fault.’ As Prior and Wilson write in their Command on the Western Front, here was an extraordinary confession. Rawlinson had not only foreseen failure but also identified its cause in advance. As we saw in the previous chapter, III Corps did ‘make a mess’ of the approach to the Hindenburg Line. This was to influence the attack on the main line in ways that no-one could have foreseen.

A PILOT FLYING in the summer sky over the Hindenburg Line on Rawlinson’s front would have seen row after row of German defences running north to south, each side of the canal. This was not like the German line east of Villers-Bretonneux at the time of the battle of Amiens. There was nothing improvised or accidental here: this was meant to be permanent, the final redoubt, heavy and Teutonic. It could not be reduced with a short barrage. And there could be no surprise. The Germans knew they were going to be attacked. They also knew that if they didn’t hold the line, they would be on the run for Germany.

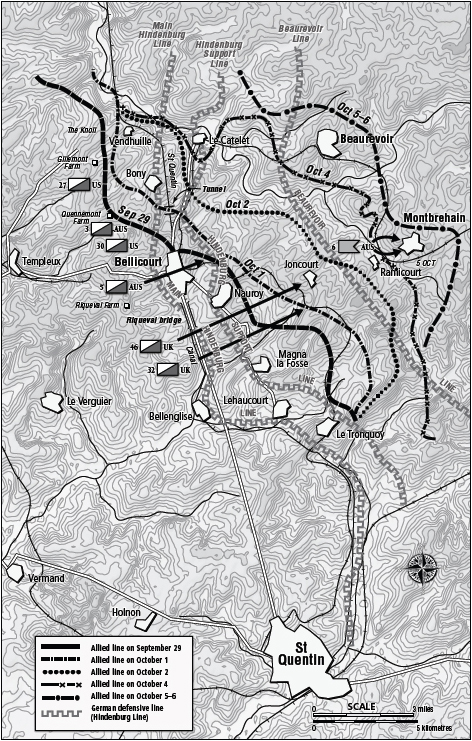

The pilot would have seen the canal, a tough enough obstacle in itself with its steep banks and dark belts of wire zigzagging each side of it. He would have seen the canal go into a tunnel just south of Bellicourt. The line of the tunnel itself was easy enough to pick up. The spoil from long ago lay banked above it, broken here and there by ventilation chimneys of grey brick. Five lines of trenches also marked the course of the tunnel. These defences along the canal and above the tunnel were the main Hindenburg Line.

Glancing to the east the pilot would have seen the reserve positions, about a mile behind the main line. These ran from the village of Le Catelet in the north, through Nauroy and on to Le Tronquoy in the south. More wire, more dugouts, more blockhouses. Two miles further east was the reserve line, known as the Beaurevoir Line because it was just west of the village of that name. South of Beaurevoir the pilot would have seen another little village, Montbrehain, out in open country.

Glancing west the pilot would have seen the new British frontline after the battle for the Hindenburg outposts. Its shape would have puzzled him. In the centre the Australian line had pushed past the Hindenburg outpost defences and was staring down the valley at the canal. But to the north the British line was up to 3000 yards behind the Australian line. Three strong German positions were intact here: the Knoll, Gillemont Farm and Quennemont Farm, all on high ground. This was the line held by Butler’s III Corps. Butler had tried to straighten it after September 18 and failed. Butler eventually told Rawlinson that his troops were too exhausted to go on.

This left Monash with a problem. He had already begun to plan his assault on the main Hindenburg Line before the battle for the outposts. He reasoned that it would be best to attack across the 6000-yard line of the tunnel with his corps as the spearhead. The casualties would be too high if he tackled the canal itself. The tunnel was a land bridge: tanks could cross it and he would not have to worry about how to get thousands of infantrymen across water.

Monash’s idea had been for the Australian Corps to sidestep to the north and take over the III Corps’ front, which faced the line of the tunnel. Braithwaite’s IX Corps would then shift north and occupy the old Australian position. Point three of Monash’s plan said that it was based on the assumption that all the objectives of the attack on the Hindenburg outposts would be taken. This, as we know, hadn’t happened on the III Corps’ front. On September 24 III Corps was still more than 1000 yards behind the start line for the new battle. The creeping barrage that would take the men to the tunnel was also based on the assumption that the start line would be reasonably straight.

Monash had a second problem: his five divisions were at half-strength or worse. He sent the 1st and 4th divisions back and brought the 3rd and 5th divisions up for the new attack. He knew these two had only one big battle left in them. He told Rawlinson that he didn’t have the means to keep the pressure on the Germans. Rawlinson said he might be able to borrow the 2nd American Corps: two big divisions untouched by war, some 50,000 men, fresh and eager. Would Monash be prepared to use them? Yes, said Monash. He now had four divisions – the two American formations plus his own 3rd and 5th – for the fight, and he could also call on the 2nd. He would use the American divisions, along with tanks, to attack over the tunnel. They would go 4000 yards, taking the main line and the reserve line. Then the two Australian divisions would pass through them and take the Beaurevoir Line, 4000 yards beyond. Butler’s III Corps and Braithwaite’s IX Corps would flood through the breach opened by the Americans and the Australians and turn left and right respectively, widening the front.

Monash’s eagerness to take the Americans and send them out to fight almost at once says something about his flustered state of mind. Of course he had to take them, but he, a logician of war, seemed to make light of their newness, their lack of knowledge of weapons and logistics. This was not going to be like Hamel or Amiens; this was going to be more like a 1916 battle: infantry trying to advance on a heavily fortified and deep line from which the Germans were unlikely to flee. Monash seemed to think that the Americans could be ‘taught’ in a few days what his own troops had taken years to learn.

RAWLINSON MODIFIED MONASH’S plan for his attack, which was due to go in on September 29. Rawlinson’s changes made sense. He thought the frontage of the assault, limited to the 6000 yards of the tunnel, too narrow. He ordered it widened to 10,000 yards so that there would be fewer casualties from flanking fire. This meant there would also have to be an attack south of the tunnel, across the water. Walter Braithwaite, the commander of IX Corps, wanted to send a division across the canal opposite Bellenglise, then pass another division through it. He selected the 46th (North Midland) Division, which had an indifferent reputation, to tackle the water. Rawlinson agreed to Braithwaite’s plan. The engineers would have to find a way of getting the 46th across the water. They came up with rafts made from petrol tins, collapsible boats, ladders and lifebelts sent up from the leave-boats at Boulogne. Rawlinson also cut down the part of Butler’s III Corps; it would do no more than guard the left flank of the Americans. Rawlinson was probably also saying that he didn’t trust Butler to do anything harder.

Rawlinson and Monash could not use the artillery as they had at Amiens. The battle for the Hindenburg Line would be a throwback. There would have to be a long bombardment, which meant there could be no surprise, as there had been at Amiens. This time the gunners would have to smash trenches and dugouts and, on the 46th Division’s front, the steep banks of the canal; they would also have to cut belt after belt of wire. And of course there would be a creeping barrage for the infantry. Here the problem caused by the failure of III Corps to take the outpost line again arose. Barrage maps had to be printed and distributed well before zero hour on September 29. Monash decided to assume that the ground Butler had failed to secure would be taken before September 29. He was gambling and didn’t like it. ‘It was contrary to the policy which had governed all my previous battle plans, in which nothing had been left to chance.’

THE POSITION ON what had been III Corps’ front became even more complicated because of Monash’s decision to sidestep his troops to the north. The III Corps front, which faced the tunnel, was now the Australians’ front, except they weren’t there. Monash had taken the chance to give his divisions a brief rest. The Americans now held the III Corps front. The 27th American Division held the northern end of the line and the 30th the southern end. And, despite the fresh attacks by Butler’s men, this front was still 1000 yards short of Monash’s proposed start line. Rawlinson decided the 27th Division would have to take the ground before the main attack on the 29th. He was asking the Americans to do what Butler couldn’t do.

EARLY ON SEPTEMBER 27 three battalions of Americans set off in the fog and rain and behind a creeping barrage to capture the German strong points at Quennemont Farm, Gillemont Farm and the Knoll. Some reached the ridgeline that looked down on the line of the tunnel. Most didn’t; most simply disappeared into the fog and for the rest of the day Monash and others wondered where they were. Some reports said the Americans had taken their objectives; others said they hadn’t. British airmen couldn’t be sure what line the Americans held. ‘Situation very obscure all day,’ Monash wrote in his diary.

It was still obscure the next day, except for one obvious conclusion: the attack had failed. It was years before the truth about that day emerged. The Americans had quickly become lost in the fog and smoke. They had gone out with only eighteen officers – many were apparently away at schools and courses – and seventeen of these had been killed or wounded. The Americans had fought bravely, but in the confusion had broken up into disconnected groups. Most of them didn’t know where they were or what to do. The attack would have been difficult for experienced troops with forty-or-so officers. The New Yorkers had been tested too severely. Their casualties ran to more than 1500.

Monash now had a dilemma, and it played on his nerves during the afternoon of September 28, the day before the big attack. A pilot reported seeing Americans out near the outpost line. If, on the following day, Monash brought his creeping barrage back 1000 yards to protect the advancing Americans, their comrades lying wounded and cut off in no-man’s land would be killed. If, on the other hand, he started the creeping barrage at the outpost line, the Americans would be unprotected by artillery for the first 1000 yards of their approach. He decided on the second option.

It was the sort of problem he hated, and not just because, as a matter of morality, there was no ‘right’ answer. So much of Monash’s confidence and authority came from the thoroughness of his preparations. He tried to win battles before they were fought, to bring mathematical certainty to warfare, so that a battle unfolded in steps that seemed inevitable and unstoppable. And here he was walking around with all these doubts that in the past he had always been able to eliminate. He was improvising and hoping. The Americans from the 27th Division might be shot up badly crossing the first 1000 yards without artillery support; the whole attack might be compromised. Monash could not be sure what was going to happen. This not only offended him but also softened his confidence.

He asked Rawlinson to postpone the battle for a day in the hope that the Americans could push their line forward a little. No, said Rawlinson, the attack was timed to fit in with other big offensives all along the line from Flanders to Verdun.

Haig arrived at Monash’s headquarters. Monash told him he was in a ‘state of despair’. Haig told him it was ‘not a serious matter’. The field-marshal was of course wrong, but larger pictures captivated him. The news from the Ypres and Cambrai fronts that day was good. To Haig, the problem was a small thing in a day of successes; to Monash, it was everything. Haig was like a country gentleman visiting his tenant farmers. He called on Major-General George Read, the commander of the American corps. ‘He is a good, honest fellow,’ Haig decided, ‘but all this class of warfare is quite new to him, and he was genuinely very anxious. I did my best to cheer him up, and told him that the reality was much simpler than his imagination pictured it to his mind.’

LIEUTENANT WILL PALSTRA, the decorated infantryman from the 3rd Division, had wanted to be a pilot from the moment he saw an aircraft flying overhead while he was training in England in 1916. On the day that the American preliminary attack failed, he was flying over the Hindenburg Line through heavy ground fire when he saw a German plane 150 yards away in the mist. He dug Devlin Hamilton, his observer, in the ribs and yelled ‘Hun’. The German hadn’t seen them. ‘Kicked on right rudder,’ Palstra wrote in his diary, ‘doing a flat turn thus giving Ham a chance with his Lewis. Ham, who like myself had been in a blue funk up to now, rose to the occasion and rattled a drum of Lewis fair into the Hun. He appeared to catch fire, large patches of smoke came from his machine and he went down in a sideslip dive. My first Hun.’

THE AMERICAN 27TH Division went out into the mist and fog just before 6 am on September 29, to be at once shot up by machine gunners who had been untouched by any barrage. Thirty-four tanks went with the Americans. Ten ran into an old British minefield, even though the Germans had marked it with signs. Another eighteen were either hit by German field guns or ditched. The heaviest fire was coming from the strong points Butler’s III Corps had failed to take: the Knoll, Gillemont Farm and Quennemont Farm. Many of the American officers were soon hit. Men who were lost or confused straggled towards the rear. Soon the American line became a series of groups, often leaderless, cut off from each other and unsure where they were. By mid-morning there was no prospect of them capturing the outpost line, let alone crossing the tunnel. Which meant Gellibrand’s 3rd Division, which was supposed to follow the Americans at around 9 am and pass through them, would also be held up.

A few hours after the attack began the American commanders didn’t know where their men were. Further back still Monash thought everything was going as it should. Then at 11.12 am he received a message from the 3rd Division saying that the Americans were stalled in front of them. Monash became more and more confused. One report would say that the Americans were across the tunnel, then another would say they were still behind the outpost line. The hamlet of Bony, on the western edge of the canal, was taken, then it wasn’t. The attack had become a replay of so many battles in 1916: as soon as the troops left the start line, the generals had no notion of what was happening.

The 3rd Division had blundered into the back of the Americans and joined them in trying to break through the outpost line. The Australians looked down on American dead and wounded in the wheat crop and peered into the fog and smoke, trying to spot the machine guns that had been stuttering since they crossed the old American frontline. They knew something was wrong but they didn’t know what. They met small parties of Americans falling back, leaderless and anxious for someone to tell them what to do.

Hubert Wilkins, the official Australian photographer, came on a group of Americans sitting quietly on the floor of a trench. A little further down the trench German stick-bombs were landing. The Americans were doing nothing because they thought the stick-bombs were shells. This was near the Knoll. An Australian lieutenant nearby collected 200 Americans and combined them with his platoon. This was happening all over the front. Americans and Australians were fighting together in isolated groups. And they still hadn’t broken through the outpost line.

To the south the men of the 30th American Division, with the advantage of a creeping barrage, had done better. They crossed the line of the tunnel, where they came under flanking fire from the outpost positions that the 27th Division had failed to reach. The Americans took Bellicourt, which had been hit hard by artillery. The task of the 5th Australian Division here was the same as for the 3rd Division to the north: pass through the Americans and go on to the support lines. Machine-gun posts that had been missed held up the 5th Division infantrymen, but they went through the Americans and took Nauroy, just behind the support line at 12.20 pm. They were more than a mile ahead of the 3rd Division, hung up to the north.

Major Blair Wark, a twenty-four-year-old quantity surveyor from Sydney, won the Victoria Cross for his leadership in this battle. He had brought the 32nd Battalion of the 5th Division through the fog and smoke south of Bellicourt, near the mouth of the tunnel, having picked up 200 Americans who were without officers, and pushed on for Nauroy before turning south-east. Here he saw khaki-clad infantrymen on his right. They were men of the 46th Division from Braithwaite’s corps. They had crossed the canal on rafts and lifebelts and seized several bridges. Theirs was the great success of the morning. Wark was delighted to see them: his left flank was still open but the Englishmen made him secure on his right. He pushed on eastwards towards the village of Joncourt, which was still held by the Germans, before halting around 3 pm. He was on the extreme right of the Australian line and, unlike most of his countrymen, close to his final objective. He didn’t know it, and Monash certainly didn’t, but the Australian frontline, instead of running roughly north–south, was a diagonal running across the main Hindenburg Line at the tunnel. Wark was at the southern end of the diagonal, roughly where the plan said he was supposed to be, and to the north Gellibrand’s division was pinned down on the other side of the tunnel, around the outpost line and the hamlet of Bony. Wark would have been in danger of being cut off had it not been for the Englishmen on his right.

THOSE ENGLISHMEN, TERRITORIALS, many of them from the mining and pottery towns of the North Midlands, had not only performed one of the memorable feats of the war in crossing the open canal; they had done so on time and with few casualties. Only when one stands on the near-vertical canal banks south of Bellicourt does one begin to understand the scale of their achievement.

The North Midlanders, shouting and cheering, had surged out of the fog and taken the German trenches on the western side of the canal with bayonet charges. Then they crossed: some swimming, some wading, others floating on rafts, lifebelts and planks. They rushed the high Riqueval bridge as the Germans were about to blow it. One of the most dramatic photographs of the war shows a brigade of the North Midlanders posing on the eastern side of the canal, some still wearing lifebelts, a few wearing captured German helmets, while their brigadier addresses them from the bridge, which is shell-pocked but intact. When this photograph was taken the division’s other two brigades had surged eastwards. Of the 5300 prisoners taken by Rawlinson’s army this day, the 46th Division took 4200; it penetrated 6000 yards into the Hindenburg defences and lost only 800 men. The North Midlanders had shown rare spirit, but the division also went forward under what was probably the heaviest barrage that had ever accompanied a British division during the Great War. The American division that had failed in the north on the same day had gone out with no barrage. The main tactical lesson of the war was on display again.

BY MID-AFTERNOON RAWLINSON seemed to think the attack was succeeding everywhere. ‘I could not have hoped for such good results,’ he wrote in his diary. Sometime afterwards he realised the Americans and the 3rd Division were stalled on the outpost line. ‘The Americans appear to be in a state of hopeless confusion,’ he added to his diary entry. He feared the American casualties had been heavy – ‘but it is their own fault’.

Was it? Rawlinson and Monash, both experienced commanders, had sent them off in a fog without an artillery barrage. Here was proof that Pershing, the commander of the American forces and a soldier of modest talents, had been right to insist that, wherever possible, his troops should fight as an independent army and only when they were properly trained. The 27th American Division lost 5000 men in the three days to September 30.

Monash didn’t know much more than Rawlinson about how the battle was going; he merely thought he did. He told Bean: ‘Well, you see what I expected might happen has happened. The Americans sold us a pup. They’re simply unspeakable.’ In the official history, published in 1942, Bean argued that Monash should have realised how raw the Americans were. Monash’s battle plan, Bean contended, had broken down because he had underestimated the human element. Bean was probably right, but we need to remember that he held Monash to a higher standard than he did Birdwood, Godley and White.

Gellibrand had gone forward just before 10 am to try to discover what was happening to his division. He went so far forward that he came under machine-gun fire. He returned convinced that the Americans on his front could not reach their final objective. Monash, on the other hand, was influenced by an airman’s report that Americans had been seen a mile past the Hindenburg Line. Monash believed that the Americans had taken their objectives and had merely failed to mop up, leaving pockets of Germans behind them. Gellibrand and his staff thought those ‘pockets’ were the main German line, which they were.

Monash told Gellibrand to attack at 3 pm and wipe out the ‘pockets’; there would be no artillery support for fear of hitting Americans further forward. Gellibrand demurred. Monash bullied him. Blamey, Monash’s chief-of-staff, told Gellibrand: ‘We have had the report [the airman’s account of where the Americans were] absolutely confirmed from a number of places.’

Gellibrand sent two brigades forward. They eventually captured Gillemont Farm, one of the strong points on the outpost line, but could go no further. Towards evening mixed parties of Americans and Australians drove the Germans off two of the other strong points, Quennemont Farm and the western side of the Knoll. The outpost line had finally fallen, but the main Hindenburg Line on this front was still a mile away and there was no hope of taking it by nightfall.

A little after 4 pm Monash decided on a new tactic: he would try to attack the Germans on Gellibrand’s front by sending troops north from the 5th Division’s positions on the other side of the Hindenburg Line. He would try to clear Gellibrand’s front from behind. He had scrapped his original plan. He also told Rawlinson that the Americans should be withdrawn.

A ‘SENSATIONAL REPORT’ arrived at 5th Division headquarters from the troops at the southern end of the St Quentin Canal. They had discovered a factory, just inside the tunnel entrance, for boiling down the bodies of dead German soldiers to obtain fats and oils that were to be used to make high explosives.

Allied soldiers in France and civilians in Britain had been speculating about the existence of such a factory for eighteen months. A Berlin newspaper had in 1917 carried a story that mentioned a ‘carcase-utilisation establishment’. The item was apparently about a rendering plant for animal carcases. It was mistranslated in Britain to suggest that the Germans were boiling down the bodies of their dead soldiers. Stories spread at the front that trains ran back into Germany after nightfall carrying bodies of dead soldiers, tied neck to heel in pairs.

The Australians and Americans at the tunnel believed they had the evidence. In a stinking chamber just inside the tunnel entrance they found a dozen hacked-up bodies, two coppers and two or three tins of fat. Bean went to see the ‘factory’ the next day. He entered a chamber that contained two coppers and a table. Twelve Germans lay dead on the floor covered with red brick-dust. One was missing his head; another’s skull was ‘cracked like an eggshell’; body parts and blood were splattered on the walls. A thirteenth German lay in one of the coppers, his head beneath the surface scum, his exposed shoulder blade showing through the grey of his coat.

The Germans had used the three-and-a-half miles of the tunnel as a shelter and dormitory. Bean promptly concluded that he was in a kitchen. Then he looked up and saw a hole. He could see the marks made by the driving band of a six-inch shell. The shell had penetrated three or four feet of masonry and earth above the tunnel, entered the chamber and exploded on the kitchen floor, throwing one of the Germans into the copper.

American and Australian soldiers were in the chamber with Bean. An American said: ‘Well, I never believed it before, but now I have seen it I can write home and tell them that I have seen it with my own eyes.’

A young Australian was more sceptical. ‘If this is the way they did it,’ he said, ‘one man at a time, all I can say is that it must be a bloody long job.’

MONASH’S POSITION AT the end of that first day was not as bad as his flights of caprice would suggest. His plan had gone wrong, communications with the northern front had broken down and he didn’t know where the Americans were and hence was limited in his use of artillery. Monash saw all these things as forms of untidiness. This, and his tiredness – he had had only six days off in six months – probably explained his flashes of temper. Mostly he argued with Gellibrand and mostly Gellibrand was right. Yet Monash was hardly presiding over the sort of shambles that had several times visited Birdwood, Godley and White in 1916 and 1917. His front was a diagonal line when the plan said it should have been a vertical line, but he had still breached the main Hindenburg Line across the tunnel. And the Germans lacked the men to mount the furious counter-attacks that had always been part of their way of war.

For September 30, the second day of the battle, Monash decided to attack north-east, rather than from west to east. The 3rd Division would go for the hamlet of Bony, on the western side of the tunnel. The 5th Division would push north-east towards the Beaurevoir Line, the last line of German defences. So began two days of grinding against the Germans during which the line edged east to the crump of bombs and the flashes of bayonets. The attack became a series of small-scale battles in the rain and mud. As Monash later admitted, there could be no methodical advance covered by artillery. ‘It was, in a peculiar degree, a private soldier’s battle,’ he said.

The privates did well. The 3rd Division crept towards Bony and finally took it on October 1. On the same day the 5th Division took Joncourt, on the edge of the Beaurevoir Line. To the north the Australians had sent patrols into Le Catelet.

Norman Dalgleish, a twenty-three-year-old lieutenant in Pompey Elliott’s brigade, kept going although wounded. Then a shell fragment hit him in the head, causing fearful wounds that left him speechless. He insisted on personally telling his superiors that his company needed reinforcements. He did so with sign language and by sketching on a sheet of paper that was soon sodden with his blood. At the hospital Dalgleish asked a nurse to help him write commendations for two of his NCOs. Then he collapsed. He died about a week later. Dalgleish’s father ‘broke down completely and cried like a child’ when Elliott’s account of Norman’s last exploit was read to him.

By the end of October 1 most of the Americans had been gathered in. Monash now had almost all of the ground he had aimed to take and around 3000 prisoners. He decided to relieve the 3rd and 5th divisions, which had run up around 2600 casualties. He would bring in the 2nd Division to take the Beaurevoir Line on October 3.

LIEUTENANT JOE MAXWELL came up with the 2nd Division. He was only twenty-two, a notorious scrapper and reveller. He also owned an impish sense of humour and a winsome smile and didn’t take himself too seriously away from the guns. He had twice won the Military Cross, as well as the Distinguished Conduct Medal.

The attack went in at 6.05 am on October 3 under a barrage that fell short on Maxwell’s section of the front. The 5th and 7th brigades made the initial assault. They could come up with only 2500 frontline troops between them for a frontage of 6000 yards. Maxwell watched his men go down, first from Australian shells dropping short, then from German fire. The wire was mostly uncut. Maxwell could see steam rising from a German machine gun: the water in the jacket was boiling but the Maxim was still firing. Maxwell rushed the post, firing his revolver as he ran, and landed among the Germans, only to realise that his revolver was empty. ‘When the Germans before us shouted “Kamerad ” I was the most pleased and relieved man in France.’

Maxwell was now in the Beaurevoir Line. A rifle cracked from one of the dugouts. An Australian sank, clutching wildly at his stomach. ‘He was dead in two minutes,’ Maxwell wrote. ‘In that dugout there were seven of the enemy. That cowardly act had to be punished. We shot every one of them.’

Later in the day an ‘impetuous’ Australian shot a German who was about to surrender. Other Germans nearby hesitated to surrender. Maxwell walked over to their trench with a prisoner as interpreter and two privates. Maxwell realised his error as soon as he arrived there. Some Germans wanted to surrender and some didn’t. ‘An officer wearing a peaked cap was bitterly opposed to any surrender. He flung gusts of excited German at his men.’ Two machine guns were pointed at the Australian trench.

A dead Australian lay among the Germans. Maxwell bent down to identify him. He gazed up into the muzzle of a German pistol. The man was about to shoot him. The officer stopped him and demanded Maxwell’s revolver. Maxwell handed it over.

The officer noticed that Maxwell had a cut on the chin and blood smears on his neck. ‘You might care for this,’ he said in English, offering Maxwell a bottle of schnapps. Maxwell hesitated.

‘It is not poisoned. We do not kill defenceless prisoners. We fight cleanly.’

Maxwell took a drink and told the officer he should surrender. ‘Our people will blow the trench to smithereens. You have no chance. Be sensible.’

The German said he would fight on. A moment later the Australian barrage fell on the trench. Men flew in the air. The German officer stood bravely in the cloud of smoke and dust. He took a shell-blast in the face and died without a murmur. Maxwell escaped to the Australian line.

THE AUSTRALIANS TOOK their 6000 yards of trench that day; south of them Braithwaite’s corps took another 5000 yards. The Hindenburg Line had been breached from front to back. The Australians might have taken Beaurevoir village too but they lacked the numbers. They had taken about 1000 prisoners; next day they rounded up another 800. The Australian casualties for three days at the Beaurevoir Line were close to 1000, a heavy loss for the low numbers involved. The Australian divisions were just about spent.

WHEN JOE MAXWELL crossed the Beaurevoir Line on October 3 he came upon an Australian with a severe head wound. Maxwell stabbed a rifle with bayonet fixed into the ground next to him, so that stretcher-bearers would see the man. ‘Two days later,’ Maxwell wrote, ‘when we passed this spot the poor fellow was still alive, but he was wrapped in the topcoat of a German whose body lay near. The German, apparently seeing his end was near, had taken off his coat to cover the Australian, whom he thought had a chance.’

There was plenty of rum for Maxwell and his men that night. They drank their issue, plus that of the eighty-odd men who had been killed or wounded. They were then ordered to the rear. Hardly a man was sober enough to walk, Maxwell said. Two months later he was told he had won the Victoria Cross.

MONASH NOW DECIDED to withdraw the 2nd Division. It would be replaced by the two American divisions, which had been given a brief rest. The Americans could not take over the front until October 5. Monash said that Rawlinson asked him to hold the front for another day and to use it to push the line further east. Monash decided to attack the village of Montbrehain.

ON THE GROUND south of the tunnel entrance one is still reminded of the weight of the barrage that supported the North Midlanders’ attack across the water. It has rained overnight and shrapnel balls, round and dull grey, have been washed into the path leading down to the canal. Near the Riqueval bridge patches of land remain unreclaimed and copses have grown up around shell holes that are filling with pine needles. Here and there are shell fragments and pieces of driving bands. The bridge is much as it was in 1918: a single lane, about fifty-feet across with low concrete sides above a high arch, a modest structure that was the scene for one of the most arresting photographs of the war.

At the entrance to the tunnel, just below Bellicourt, the water is still and slimy green. You start when a fish jumps near the brick banks. A plaque above the entrance says that Napoleon, emperor and king, started the canal in 1802. Just below the sign you see where slits for machine guns have been mortared over. Behind those slits was the kitchen that some thought was a corpse factory.

The American cemetery near Bony is beautifully kept. Instead of headstones, white marble crosses and an occasional Star of David mark the American dead. A notice forbids skateboarding, roller-skating, bicycling, motorcycling and ball playing. Among all the nations with cemeteries on the western front only the Americans see the need to remind people not to do these things.