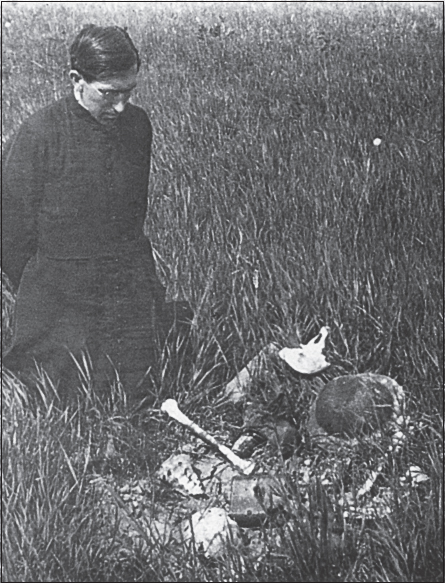

All that’s left of a life: bones, badges and scraps of uniform shivering in the wind. This photograph was probably taken in the summer of 1919. The priest from Fromelles kneels before the remains of a British or Australian soldier killed in the battle of July 19, 1916. Martial Delebarre from Fromelles (who supplied this photograph) in 1992 found a bone-handled knife on the old battlefield. Scratched on the handle was ‘G Blake’. Private George Francis Blake, a carpenter from Footscray, Victoria, died here in 1916. Bodies from the Great War are still being found. Most cannot be identified, although buttons and badges often give a clue to the nationality of the soldier. Such men are buried under a headstone that says they are, ‘Known Unto God.’

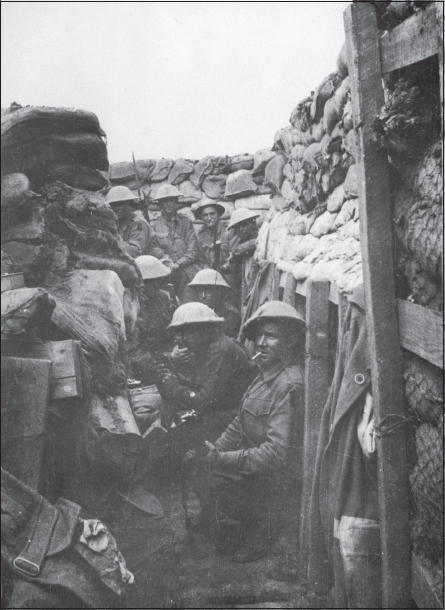

Before: men of the 53rd Battalion of the 5th Australian Division waiting to ‘hop the bags’ at Fromelles. Because of the high water table, there were no trenches here but breastworks built above the plain. Only three of the men in this photograph came out of the battle alive, and all three were wounded. [AWM A03042]

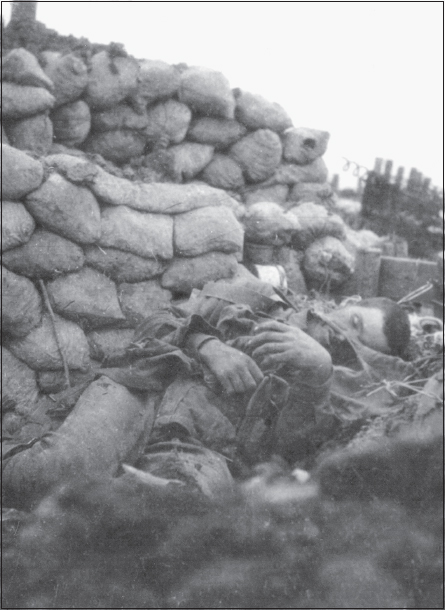

After: the body of an Australian killed inside the German lines on the waterlogged plain at Fromelles. Captain Charles Mills was wounded in the hand there and taken prisoner. After the war a German officer gave him this and other photographs taken on July 20, 1916, the morning after the failed attack that resulted in 5500 Australian casualties. It was years before the extent of the Australian tragedy at Fromelles became known.[AWM A01566]

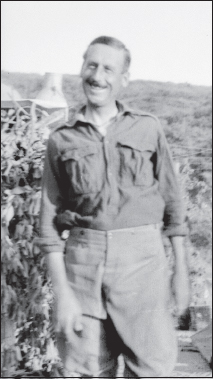

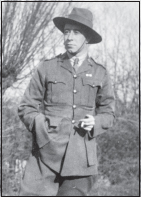

Brigadier-General ‘Pompey’ Elliott in a characteristic Australian pose outside a captured German headquarters late in the war. One of the true eccentrics of the Australian Imperial Force, Elliott was tyrannical and tender, blustering and subtle, cocksure and insecure. He liked to look dishevelled, particularly if there were ‘foppish’ English staff officers about. He was one of the fabled ‘fighting’ leaders of the AIF. He wept behind the Australian breastworks at Fromelles after his 15th Brigade had taken shocking casualties. [AWM E2855]

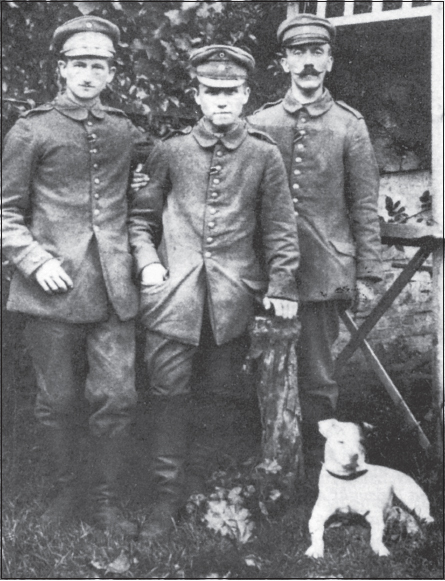

The monster in his formative years, long before he and Benito Mussolini (who also fought in the Great War) introduced the dress code for fascism. These German soldiers are behind the frontline at Fromelles in 1916. Corporal Adolf Hitler (right) had adopted a dog that strayed over from the allied lines and taught it tricks. He was billeted above a butcher’s shop in a village near Fromelles and the old French woman who looked after him called him ‘Blackie’. There is much of the bumpkin about Hitler here, aged twenty-seven and inclined to throw tantrums if the barrack-room talk turned glum. George Orwell stared at a photo of Hitler in 1940 and detected self-pity in his face. Hitler was at Fromelles when the Australians attacked on July 19.

The German blockhouse called the Windmill on a little hill east of Pozières. Some 23,000 Australians fell within a mile or so of here. The site is today the best spot from which to view the Somme battlefields of 1916. [AWM E03375]

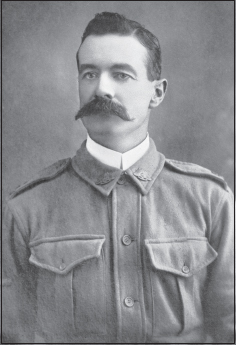

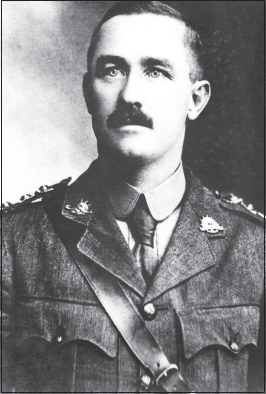

The knight of the doleful countenance - 1: General James McCay commanded the Australians at Fromelles. On his death the Bulletin described him as ‘about the most detested officer’ in the AIF. He showed much bravery on Gallipoli but could not inspire those under him, let alone win their affection. [AWM H01890]

The knight of the doleful countenance - 2: Sir Richard Haking, who, more than anyone, was responsible for the madness at Fromelles and its 7080 Australian and British casualties. Haking didn’t understand the new warfare and the importance of firepower. He seemed to think trenches could be taken by acts of ‘character’.

Routes to a war. Sausage Valley, the road to Pozières. The white dust of the road comes from the lumps of chalk in the soil here. The vehicle in the foreground is a Rolls-Royce Phantom; behind it are field kitchens.

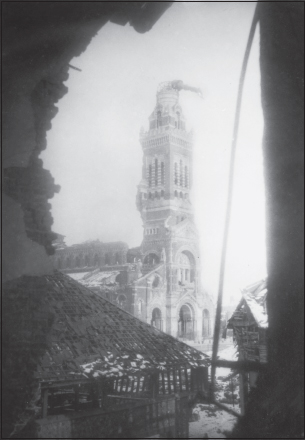

Before they reached Sausage Valley, Australian and British troops passed the Hanging Virgin in Albert. The sight of it at night was eerie. [AWM EZ0113 (above) and E167]

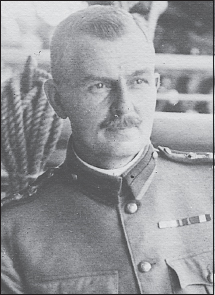

Hubert Gough, the British army commander under whom the Australians served at Pozières, Mouquet Farm and the two battles of Bullecourt in 1917. Gough was rash, headstrong and prickly. The cavalry charge was forever playing in his head; he didn’t want to be held up by detail or doubters. Gough’s rise had been fast and bore little relationship to his achievements. It owed much to the patronage of Sir Douglas Haig, the British commander-in-chief on the western front.[AWM H12215]

Harold Walker, an Englishman, commanded the 1st Australian Division for much of the Great War. Australia owes him more than it has ever acknowledged. [AWM ART03349]

James Gordon Legge commanded the 2nd Australian Division at Pozières. Unlike Walker, he was unable to stand up to Gough.[AWMC01011]

The main street of Pozières in 1914. The Roman road runs away towards the Windmill on the eastern outskirts of the village.

The same main street two years later. [AWM G0 15341 (top) and EZ0095]

Pozières from the air just before it was destroyed by artillery fire. The Roman road runs diagonally across the photograph, from lower left to upper right; the village is in the centre. The two lines curving from top to bottom on the right of the village are the trenches known as the Old German (OG) lines, 1 and 2.

Germans in a trench near Pozières. Note the white chalk thrown up from their evacuations. [AWM J00275 (above) and J00213 (left)]

One of the shining lights that went out at Pozières. Captain Ivor Margetts, a Tasmanian schoolteacher who was killed in the early fighting for Pozières village. He had fought on the heights above Anzac Cove on the first day of the Gallipoli landing in places never again held by Australians. After he was killed a private wrote: ‘I cried like a kid when I found he was dead. I think he went because he was too good for the beastliness of war …’ Margetts was buried close to where he fell. A photograph of his grave, an over-bright white cross in a sea of shell holes, was taken in 1916 and appears on the front cover of this book. The grave was lost in later fighting. All we now know is that Ivor Margetts lies in the ground somewhere at Pozières.

The one-man epic: Captain Albert Jacka, the best-known ‘fighting’ soldier in the AIF. A forestry worker from northern Victoria, he won the Victoria Cross on Gallipoli, the Military Cross at Pozières (where many believed he should have received a second VC) and a bar to his MC at First Bullecourt in 1917. He was badly wounded at Pozières and gassed in 1918 at Villers-Bretonneux. A cult grew up around Jacka after the war. He died aged thirty-nine, partly as a result of his war wounds. [AWM P02939.001]

Before: Mouquet Farm, north of Pozières, in peacetime, a rustic fortress of red and chalk bricks.

After: the farm after the fighting of 1916. All that marks the site of the farmhouse today is a small pile of German concrete and French bricks in a field grazed by sheep.[AWM J00181 (above) and E00005]

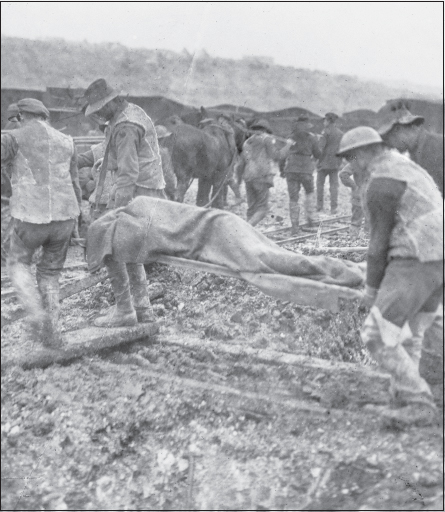

Stretcher-bearers bringing back a casualty during the ‘terrible winter’ of 1916-17. This photograph was taken near Delville Wood, just behind the Australians’ winter line. The mud was so thick that stretcher-bearers sometimes took twelve hours to carry a wounded man two or three miles. Men pulled out of the mud often left their boots and trousers behind. [AWM E00049]

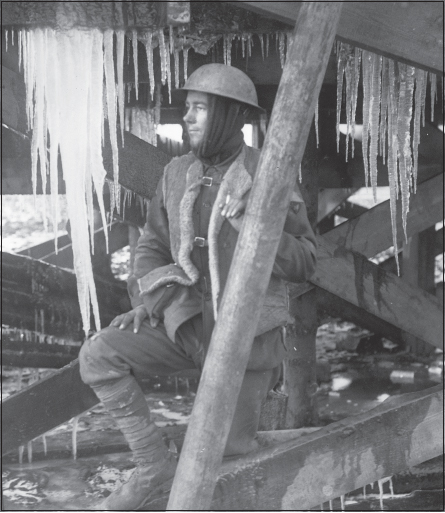

Framed by icicles, a 2nd Division man in sheepskin vest and balaclava looks out on the frozen landscape that was the Australian front. Just before Christmas, 1916, German and allied troops sometimes walked about their parapets in sight of one another. Both sides were more interested in draining their trenches than shooting at each other. Australians stayed in the frontline trenches for just forty-eight hours at a time. Many came down with shivering fits and trench foot. Some said afterwards that the winter of 1916-17 was their worst memory of the war. [AWM EZ0123]

Charles Bean, the official Australian war correspondent, struggling along a mud-filled trench near Gueudecourt. Bean liked to obtain his material first hand. Brudenell White, the chief-of-staff of the Australian Corps, said after the war that Bean faced death more often than any man in the AIF. [AWM E00572]

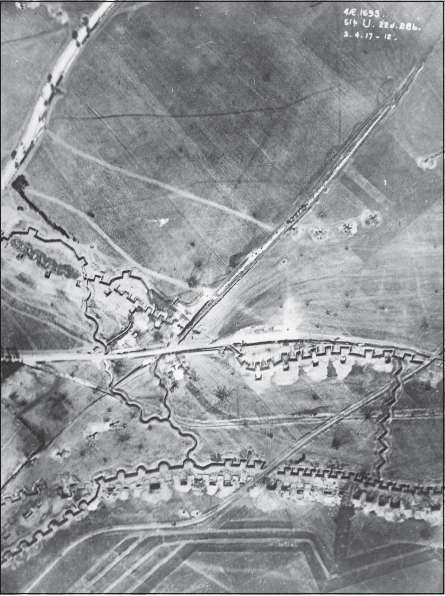

The formidable defences of the Hindenburg Line east of Bullecourt village, photographed from the air a week before the first Australian attack in 1917. The notched lines are the two Hindenburg trenches. German batteries can be seen behind the second line on the right of the photograph. The grey bands in the foreground are uncut wire. [AWM A01121]

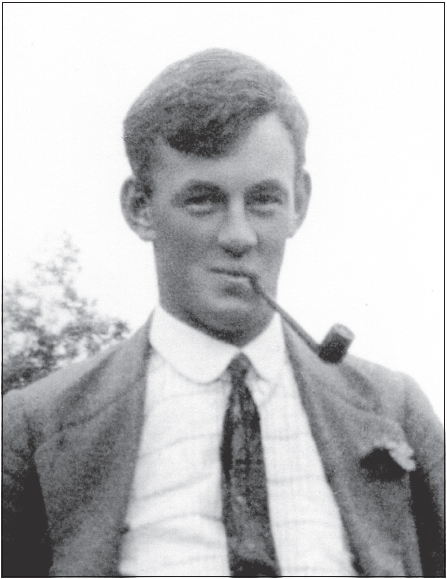

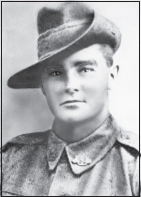

Harry Murray, from Evandale, Tasmania, became the most decorated infantry soldier in the British empire armies of the Great War. He won the Distinguished Conduct Medal on Gallipoli, the Distinguished Service Order at Mouquet Farm in 1916, the Victoria Cross at Stormy Trench in 1917 and a second DSO at Bullecourt later in the same year. The French awarded him the Croix de Guerre. No cult developed around Murray, a modest and reflective man. After the war he bought a grazing property in outback Queensland and told Charles Bean he was teaching his sheep to march in fours. [AWM P02939.053]

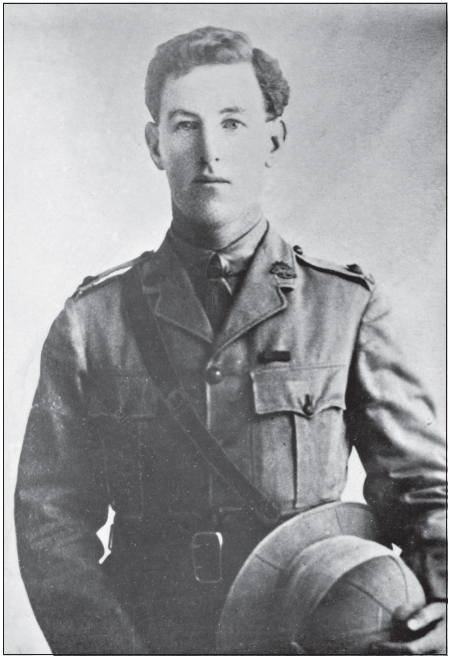

Percy Black, born at Bacchus Marsh, Victoria, was Harry Murray’s best friend. Both were working in Western Australia when war broke out, Murray as a sleeper-cutter and Black as a prospector. Black died on the uncut wire at First Bullecourt. By then he had won the Distinguished Service Order, the Distinguished Conduct Medal and the Croix de Guerre. Murray said Black was ‘the bravest man in the AIF’. When a barrage was falling Black would walk along the line, look down at a private cowering in a trench or shell hole and say: ‘Got a match, lad?’ [AWM J00369]

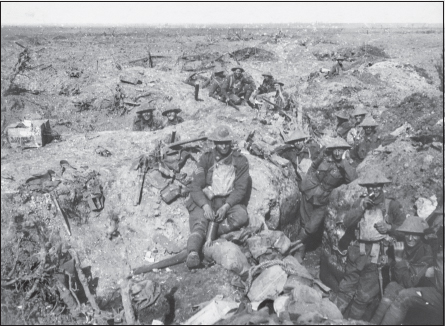

Australians holding the first line of Hindenburg trenches during Second Bullecourt. Nearest the camera is Lieutenant William Donovan Joynt, who won the Victoria Cross the following year. [AWM E00439]

The debris of war: the railway embankment that ran parallel to the Hindenburg Line at Bullecourt. Both Australian attacks began from here. [AWM E1408]

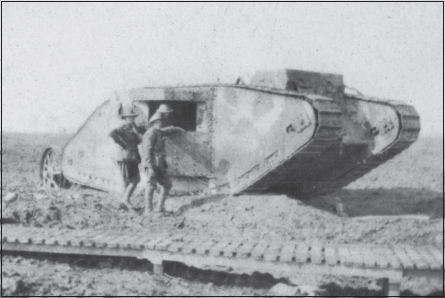

A crippled Mark I tank, the type used at First Bullecourt. The Great War was all about new technology - submarines, machine guns, quick-firing artillery, aircraft - but these, and other relatively new inventions, predated the conflict. The tank was conceived during the war, as a means of crushing wire and crossing trenches. The Mark I weighed thirty-one tons and had a top speed of 3.7 miles per hour.[AWM P00826.001]

Rupert ‘Mick’ Moon, winner of the Victoria Cross at Second Bullecourt, where a bullet smashed his jaw and twelve teeth. [AWM A02592]

Phillip Schuler, who wrote so well of Gallipoli as a journalist and died in Flanders as a soldier. [AWM G01560]

The ruined Cloth Hall at Ypres, 1917. Only soldiers and rats lived here. Most Australians who passed through the town on their way to the war thought it so ruined by shellfire that it could never be restored. But it was. Ypres today is one of the most beautiful and hospitable places along the old line of trenches that stretched south and east to Verdun. [AWM E1230]

Dead and wounded Australians and Germans in the railway cutting on Broodseinde Ridge during the battle for Passchendaele village.[AWM E03864]

Fred Tubb won the Victoria Cross at Lone Pine on Gallipoli. He was one of several distinguished soldiers who sprang from the congregation of a little wooden Anglican church among gums at Longwood in Victoria’s north-east. Tubb was killed in the battle of Menin Road. [AWM H06786]

Australian troops in craters on the edge of Polygon Wood - except the wood has been obliterated by artillery fire. [AWM E00971]

The Seabrook brothers from Five Dock, Sydney: Theo (left), William (centre) and George. All were killed in the battle of Menin Road. Several Red Cross reports have Theo and George being killed by the same shell.[AWM H05568]

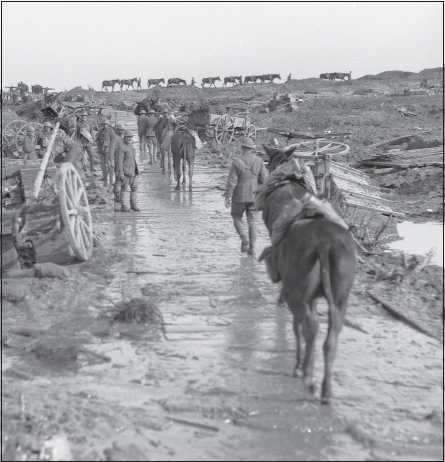

The way to the war, paved with bad intentions. Menin Road, near Idiot Corner, late in the Passchendaele campaign. [AWM E01197]

Jarvis Fuller (top), from Moonambel in Victoria’s west, his brother Roy and four of their sisters. Jarvis ‘disappeared’ in the fighting at Broodseinde. Roy, who was in the same battle, months later discovered that his brother had been buried by another battalion. [Valma Harris]

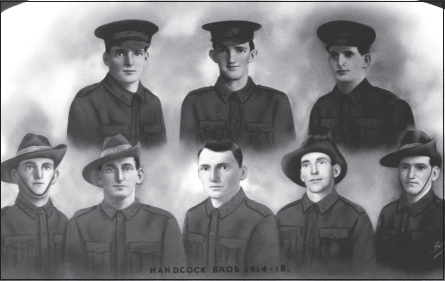

Eight brothers from the Handcock family of Myrrhee, near Wangaratta, went to the Great War. Jack (top row, centre) was killed on Gallipoli. Frank (top row, right) lost a leg at Broodseinde. Charles (bottom row, second from right) died from pneumonia a day before the war ended. [Colin Handcock]

Frank Hurley, one of the official Australian photographers, was a master of composition. All of his work bears a signature: you know it is a Hurley before you read the credit line. Here he captures Australian artillerymen crossing the flooded Ypres battlefield in late October. [AWM E01220]

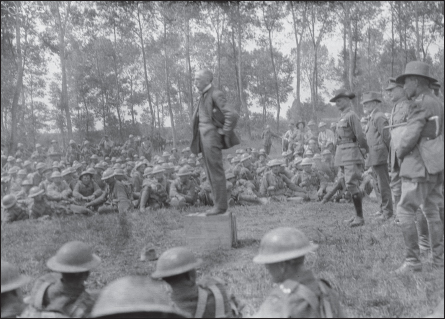

Billy Hughes, the Australian Prime Minister, twice failed to introduce conscription at home. Here he addresses troops in France late in the war. As Australia went to war in 1914, Andrew Fisher, the Labor leader, said Australia would support Britain to the last man and the last shilling. When Hughes, who succeeded Fisher as prime minister, turned up behind the lines in France in 1916, soldiers joked that Fisher indeed had sent the last man. Hughes had great affection for the Australian soldier.[AWM E02651]

Keith Murdoch (right) played journalist and courtier from London for the last three years of the war. He wrote for a string of newspapers in Australia while also acting as Hughes’ agent and emissary. [AWM E02650]

An Australian infantryman uses his .303 rifle to ease the weight of his pack during a halt in the pursuit of the Germans to the Hindenburg Line early in 1917. Charles Bean said Australian troops were always easy to recognise from a distance because of their ‘easy attitudes’. Australian and New Zealand troops only began referring to themselves as ‘Diggers’ late in 1917. [AWM E00227]

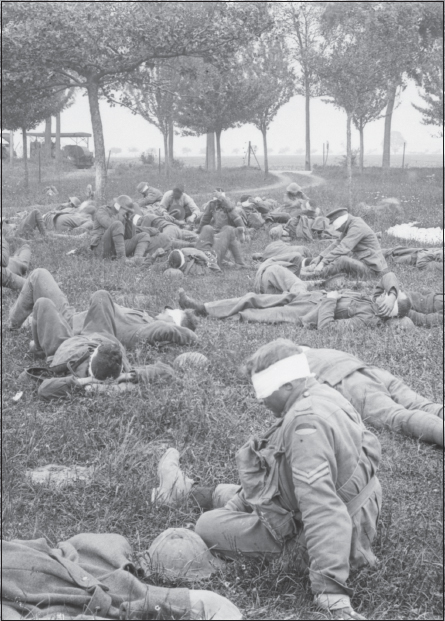

Gassed, blinded and bewildered: the morning after a gas attack, near Villers-Bretonneux, late May, 1918. Australians, some blinded, at an aid post after being hit by 18,000 gas shells, many of them mustard, in the previous two days. Mustard gas caused blindness (usually temporary), swelling of the eyes and eyelids, vomiting, and burns and blisters to the skin. By 1915 the German, French and British armies were all using gas as a weapon of terror. About three per cent of gas casualties turned out fatal, but the figure is misleading. Many who had been gassed returned home with chronic bronchitis and skin rashes and died young. [AWM E04851]

Fresh from the frontline, troops from the 5th Division playing football in mid-September, 1918. [AWM E03356]

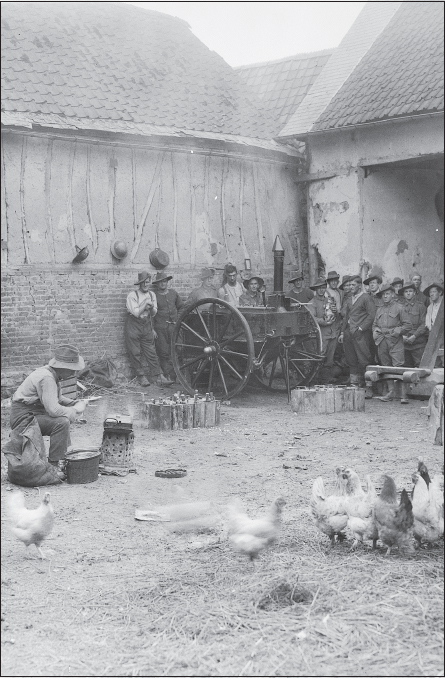

A typical scene inside the courtyard of a French farm being used as a billet for Australians in 1918. The men are clustered around a field cooker. The fowls are in some danger should their owner look the wrong way. [AWM E02297]

Sir William Birdwood, a British cavalryman who always looked neat on a horse, had charge of the Australian forces throughout the war, although he handed over the field command to John Monash in 1918. He had affection for Australians and understood the way they thought. Birdwood was no tactician or organiser. His gift lay in building morale. He would pop up just behind the frontline to shake hands with privates from Bendigo or Dubbo. They mostly decided he, ‘wasn’t a bad sort of cove’. [AWM E00537]

Brudenell White, Australian born, was Birdwood’s chief-of-staff. He was good at the things Birdwood was not: organisation and staff work. [AWM G01329]

Sir John Monash, the son of Jewish immigrants and a Renaissance man of commanding intellect, led the Australian Corps to a string of victories in 1918. Monash was a ‘modern’ man who understood war in the industrial age. It was probably to his advantage that he did not come from the military establishment. He proved himself a master of the set-piece at Hamel and of the fast-moving battle at Mont St Quentin. Few Australians have better claims to greatness. [AWM E02350]

Bertangles Château today. This was Monash’s headquarters when he took over the Australian Corps. Before the battles of Hamel and Amiens, Monash paced the gravel drive, waiting for the thunder of the artillery barrage. [Denise Carlyon]

Arthur Currie, the citizen-soldier who commanded the Canadian Corps. His figure might have been unsoldierly but, like Monash, he was one of the great generals of the war. Currie liked to visit the front to see the battlefield first hand. He has perhaps never received the acclaim he deserves. [AWM H06979]

Handsome, yes, but with a cold stare. Baron Manfred von Richthofen, the German air ace, liked shooting things: boar, deer, elk, rabbits, birds (including three pet ducks belonging to his grandmother) and allied aircraft - eighty of them. He was killed, probably by Australian ground fire, in the Somme valley in April, 1918, and buried near Bertangles Château. Hermann Goering took over Richthofen’s ‘flying circus’. [AWM A04803]

An Australian platoon, now reduced to just seventeen men, resting during the battle of Amiens. By now the Australian fighting numbers were low - there were virtually no new recruits - but the men left were hard and experienced. [AWM E02790]

Georges Clemenceau, the French Prime Minister, with Major-General Sinclair-MacLagan, commander of the 4th Australian Division, after the battle of Hamel. [AWM E02527]

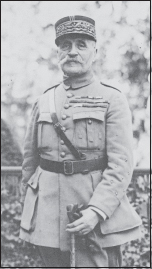

Marshal Ferdinand Foch of France: no man imposed his personality on the war as robustly as Foch. [AWM H09473]

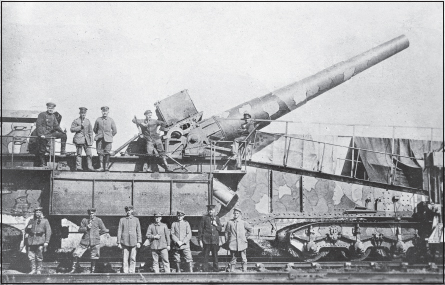

The Great War was all about artillery. More than half the deaths may have been caused by shellfire; bayonets caused about one per cent. The barrel of this German gun, captured during the Amiens battle, is now on display outside the Australian War Memorial, Canberra. [AWM P01887.001]

Kamerad: Germans surrendering to Australians several miles west of the Hindenburg Line in September, 1918. [AWM E03274]

An Australian searches a German prisoner for ‘souvenirs’ in late 1918. High on the list of desirables were watches, shoulder straps, binoculars and Luger pistols. A German officer captured at Broodseinde in 1917 said: ‘Your men are funny. They rob while they fight.’ He was then given a cup of tea. [AWM E03919]

Charles Bean explains the Mont St Quentin battlefield to Billy Hughes. [AWM E03292]

Lieutenant Joe Maxwell, VC. [AWM P03390.001]

Private Robert Mactier, VC. [AWM H06787A]

Lieutenant William Donovan Joynt, VC. [AWM P02939.034]

Lieutenant Eric Edgerton. [Ian Clarke]

Lieutenant Cyril Lawrence. [AWM P02226.001]

Kaiser Wilhelm (centre) with his army commanders Paul von Hindenburg (left) and Erich Ludendorff. By 1918 Hindenburg and Ludendorff were effectively running Germany, and Ludendorff was running Hindenburg. [AWM H12326]

A Château, wrecked by shellfire in 1918, shows its wounds to the world at Villers-Bretonneux in 2003. [Denise Carlyon]

Harry Fletcher (left) and Austin Mahony (right). They lived in the same boarding house near Melbourne University before the war. They enlisted together and went to Gallipoli together. They both died at Montbrehain in October, 1918. Montbrehain was the last Australian infantry action of the War. [AWM P03668.006]

Adelaide Cemetery, Villers-Bretonneux, 1919. French children tend the graves of Australian soldiers. The long mourning has begun. [AWM E05925]