2

VERNACULAR

Think for a minute about what it would be like to live before the discovery of fossil fuels. It would be a lot more challenging than just giving up some modern conveniences. It would probably be a lot like camping year-round—except that you would have to cook everything over a wood fire. And you couldn't load up your car and drive home if it started to rain or when winter rolled around. But this is essentially the way people lived until the past few generations. They had to find a good way to fit in with their climatic environment or they simply didn't survive.

Humans are remarkably resourceful, though, and our ancestors were able to develop ways to survive quite nicely in every environment on earth. Want to live in the desert, the tundra, or the jungle? No problem. People found ways to work within the limits and constraints of their environments. If it was really hot for part of the year, they didn't have the option to install central air. Instead, they figured out ways to stay cool by creating thermally comfortable microclimates. However, after the discovery of fossil fuels, the need to fit a building into the local climatic environment became less important. Buildings could be constructed with a central heating and air-conditioning system that allowed the interior to be climate controlled and thus thermally comfortable at all times. As a result, many of the traditional ways of staying comfortable have been lost or forgotten.

But a lot can be learned by looking at the way people used to live in different climatic regions. And there are many traditional patterns on the land that we can analyze, many of which still exist in various forms. In many ways, the landscape is like a palimpsest—an ancient parchment that was written on, then erased and written on again. Grocery lists got erased, while important or valuable information survived. In the landscape, if someone tried a technique for making their home environment more comfortable or their fields more productive and it failed, it would have been erased. Landscapes that are microclimatically appropriate tend to survive and offer much that can be learned. In this chapter, we'll browse a few examples of patterns on the landscape that have persisted, and we'll try to elucidate some of the reasons they succeeded.

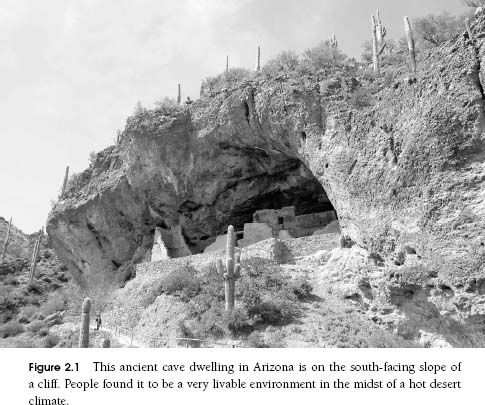

The first desert traveler who spent a night in a south-facing cave probably found it to be a good place. Based on the number of surviving examples, it apparently became accepted practice for people living in the Sonora Desert in North America to live in caves (see figure 2.1).

Winters in the caves would have been toasty warm with solar radiation streaming in from the low-in-the-sky sun, while summers would have been pleasantly cool with solar radiation from the high-in-the-sky sun blocked by the overhanging rock. The cool winter winds were blocked by the sides of the cave. The thick rock walls buffered the cold in the winter and the heat in the summer.

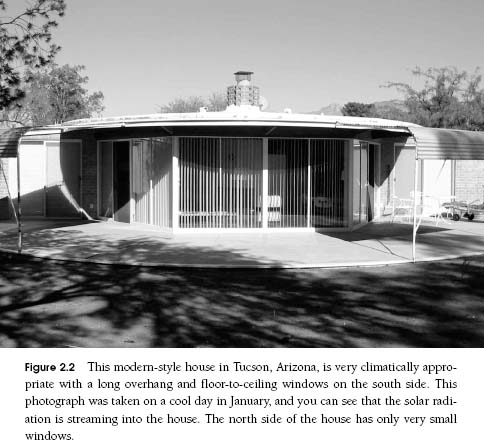

People no longer live in these places, but they have inspired many design instructors to use principles based on these early residences in their lectures. They tell their students that buildings should have most of their windows on the south side and that each window should have a long overhang above it. This allows the sun to enter and warm the interior during the winter, and the overhang keeps the solar radiation out in the hot summer. Few windows should be on the east, north, and west walls, and all walls should be well insulated. The design of houses can vary greatly as long as these basic principles are followed. For example, the Arthur Brown house in Tucson, Arizona, has almost all the windows on the south face, and there is a movable structure that can be rolled around to strategically shade areas in the house and yard (see figure 2.2). During cool winter days, the sun streams in through the south-facing windows, bathing the interior of the house. On hot summer days, the sun is kept out of the house by the overhang and the movable shading devices, leaving the house shady and cool. Similarly, the living space just outside the sliding glass doors on the south side of the house is a very pleasant place to be almost any day of the year.

The people living on the North American plains when European settlers arrived had finely tuned their living environments to fit into the harsh continental climate. In the area currently known as Saskatchewan, the people of the plains lived in portable homes called tipis. These structures were made of animal skins laid over a framework of stout poles to form a conelike shape. There was an entry flap that would open on one side, and an opening at the top to allow smoke to exit. During the winter, both the opening at the top and the entry flap would be oriented away from the wind, and the entry flap would be tightly closed except to allow entry and exit. As the wind passed over the top of the tipi, it drew smoke from the top opening but didn't flow in. During summer, the opening was oriented toward the wind but the flap was oriented away from the wind and was often left at least partly open. This combination allowed wind to enter the opening at the top, flow down through the tipi, and exit through the lower flap, cooling and ventilating the tipi.

During the summer, tipis were located on tops of hills to capture the most wind possible. As wind moves up and over a hill, it is forced to compress slightly as the ground rises, and the speed of the wind increases. The windiest spot in the landscape is often at the crest of a hill, and this is where the tipis were often located. Not only did this provide increased ventilation and cooling, but it also helped to ward off the scourge of the prairies—mosquitoes! These stinging insects cannot maneuver well in wind, so they hide in the grass until the wind abates. A fairly constant wind ensures a reasonably mosquito-free time.

If you have an opportunity to wander through the hills of south-western Saskatchewan on lands that have not been turned into cropland, you will almost certainly come upon tipi rings on the tops of the hills. The edges of tipis were held down with rocks, and when the tipi was moved the rocks remained in a circle. Standing among these tipi rings, you come to realize some of the other advantages of living on the crests of hills—such as the spectacular views and the ability to receive ample advance warning in the case of an enemy attack.

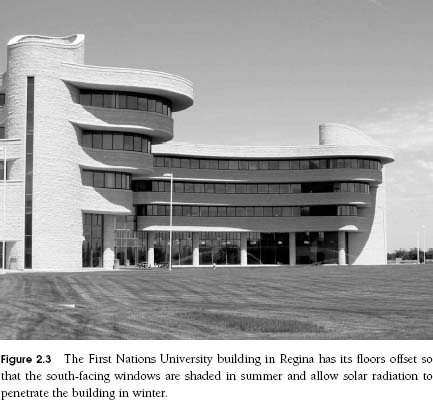

Smack dab in the middle of the remarkably flat glacial lake bed that provides Saskatchewan with its reputation as a flat province is the First Nations University. Housed in a building designed by Douglas Cardinal, it sports many indigenous characteristics. One very clever and effective design feature is the way overhangs were provided over south-facing windows. Cardinal used the floor above (see figure 2.3)!

There are many other areas in the world where people are still living with ancient patterns that can be analyzed. The traces are particularly strong in Japan, a land where traditions are celebrated and ancient patterns persist through cultural and social celebrations.

Japan has a long history of caring about design. Flower arranging, for example, is a high art form that follows a set of unbreakable and incomprehensible (to me) rules. The art form is called ikebana and has its roots in the sixth century (!). One ikebana school can trace its recorded history back to 1462. In Japan, design is not a trend; it is an institution. And it goes beyond flowers—virtually every part of Japanese life is carefully and thoroughly designed. Visiting the famous gardens of Kyoto is an interesting experience for foreigners. Actually just visiting Japan in general is mind-bending.

Before my first visit to Japan, I dutifully learned a few words and phrases in Japanese so I would be able to converse with the locals. All through the long flight over the north of Canada and down the Kamchatka Peninsula, I practiced my konichiwa and sayonara and thought I was really doing something when I could say without stumbling domo arigato gozaimasu. I expected to be saying that a lot since it means “thank you very much.” However, it wasn't until too late that I realized that I should also have learned to say yukkuri hanashite kudasai, which means “please speak slowly.”

Fortunately for me, quite a few Japanese people, especially in Tokyo, know how to speak a little English and are anxious to do two things: help tourists and practice their English. Stand on a street corner with a map in your hand looking helpless and within seconds someone will come up and offer to help.

This helped me on numerous occasions and allowed me to meet a lot of Japanese. Through these broken English conversations, I learned much about the people and the culture. People stopped me on the street to point out a flower that had just bloomed. Or to make sure that I took the time to listen to a bird singing in a tree. They seemed so aware of the beauty in the environment—even everyday environments.

Through research projects over the years, I have managed to see much of rural Japan. By visiting ancient villages and farms. I've been able to observe the traditional patterns on the land—the palimpsest of the Japanese landscape.

One project was a book that I coedited with some Japanese colleagues on the traditional rural landscape of Japan known as the satoyama. The book focused primarily on the agricultural and land use patterns and how they have changed over time, but the patterns are also instructive in terms of microclimatic design. They illustrate the powerful role of the micro-climatologic concept of orientation.

Satoyama landscapes throughout Japan have a clearly identifiable pattern. The ideal satoyama has forested hills or mountains on the north, with the settlement on the south-facing lower slopes. To the south of the settlement is the area reserved for dry field crops, and to the south of this are the paddy fields. Oak trees on the hills are regularly harvested about every ten years through coppicing. The stumps sprout at the base and grow stout stalks that are ready to be cut again in another ten years. The houses to the south of the hills have good access to solar radiation in the cool winter months, when the sun is low in the sky. The satoyama landscape provides a system by which people can live sustainably on and use the land over a very long period of time. Everything in their lives is adapted to the micro-climate—especially the homes.

Traditional houses in Japan respond well to microclimate through their orientation and design. More than seven hundred years ago, the Tsurezuregusa (roughly translated as Essays in Idleness) provided advice on house design that is still being followed today. The Tsurezuregusa suggested that homes in Japan should be designed to deal primarily with the hot, humid summers and that designers shouldn't worry too much about designing for wintertime. Winters will take care of themselves. Houses are traditionally heavy, timber-framed buildings with walls that can be slid open or closed. In the hot summer, the houses are opened to allow air movement, while in winter they are closed to keep out the cold. Oversized roofs keep out both the rain and the sun during the summer but allow solar radiation to stream into the interior during the cool winters.

When I travel in rural Japan, I like to stay in small local inns known as ryokans (the r is almost silent, so it is pronounced like yo-con, with no emphasis on either syllable). There are some wonderful but bewildering ceremonies that must be followed when checking in to a ryokan. The signing of the register is a fairly long and formal event that involves drinking several cups of green tea while sitting on the floor around a low table. On one of my stays, it was winter and the house had been designed, as the Tsurezuregusa suggested, for summer time. Many of the walls were made of rice paper, and the interior of the house was quite cool, almost cold. We crossed our legs and put our knees under the table, and I noticed that everyone was pulling the edge of the table covering to their waists so I followed suit. At this point, I became aware of a small heater under the table. The heat was kept under the table by the heavy cloth, so only a small amount of energy was needed to warm this small space. Once my legs were in that space, I was toasty warm from my waist down. The hot tea heated my core, and I have to say that I was remarkably comfortable despite the cool interior of the room. In addition, the sun was shining into the space, brightening it up and warming surfaces through absorption of solar radiation. Rather than heating the whole space, the strategic heating of only the people was very energy efficient and very comfortable.

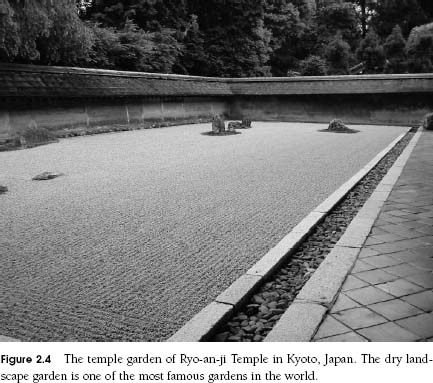

When I spent a term as visiting professor at the University of Tokyo, I joined a group of graduate students on a field study of the gardens of Kyoto. Of course, the garden at the top of our list was Ryo-an-ji (again the r is almost silent, so it sounds more like yo-on-jee, with no emphasis on any of the syllables). Volumes have been written about the garden's subtle beauty and its ability to inspire people to meditate and become at peace with themselves.

The garden at Ryo-an-ji Temple in Kyoto is ancient by anyone's standard. There has apparently been a temple on the site since about 983, and the last redesign of the garden took place in about 1488. Nothing much has changed since then—except that now it has become a superstar and everyone wants to see it.

Every day, people from throughout Japan and around the world flock to Ryo-an-ji, pay the five-dollar admission fee, and then sit and gaze out over a ten-by-thirty-meter white gravel pad that has some bigger rocks jutting through.

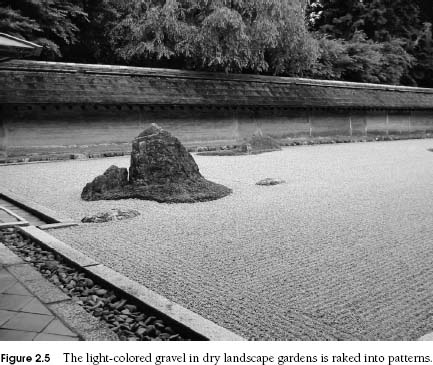

My first impression was of a very simple, very elegant garden (see figure 2.4). I was immediately struck by the feel of the place. People were sitting along the edge serenely gazing at carefully raked gravel and islands of rocks. The primary function of the garden and the adjacent building was originally to provide a place for monks to reproduce manuscripts. They would sit for long hours, cross-legged on a tatami mat, and copy documents by hand. They had to do this year-round, so they required a place that had sufficient light, was thermally comfortable, and had a contemplative environment.

The buildings were oriented to the south to allow sunlight to enter the room during cool winter days. As in many Japanese structures, the walls were movable, and the south wall of the building could be opened completely to allow total access to the garden. The garden to the south of the building was covered with white gravel that would allow solar radiation to be reflected into the room. The sunlight was important both to warm the monks and to provide light so they could see what they were writing. The white gravel was susceptible to growing moss and becoming covered with leaves or other debris, all of which would reduce the amount of reflected light, so the monks would regularly rake the gravel to ensure that the surface was as clean and light colored as possible (see figure 2.5). This raking became an art form in itself, as the rakers began to create patterns in the gravel. These patterns change with each raker, as well as with the mood of the raker.

Trees were kept out of the garden to keep from blocking the important sunlight or dropping leaves on the gravel. A wall delimited the garden, partly because of the space restrictions but also to reduce the winds in the winter. The more calm the air during the cool periods, the more comfortable for people living and working there. The wall also played an important role during summer. Cool air could “pool” in the garden and would not flow out. Also, for summertime conditions, a large overhanging roof was built over the platform on the south side in front of the writing room. The high sun angle during summer meant that the whole writing space was shaded. The white gravel reflected much of the solar radiation reaching the garden, so the input of solar radiation was greatly reduced and the garden was kept cooler. A person standing in the garden would receive a very high radiation load on a sunny summer day, but the only people allowed into the garden are the monks who rake and maintain it, and they complete their work in the early morning before the heat of the day.

Once the basic layout of the garden was determined based on function and microclimate, a framework was established within which individual monks or orders of monks could apply their creativity. They had many hours to contemplate the space and decide where to locate rocks, how to rake the gravel, and so on. The microclimate determined the framework within which is now one of the most wonderful places in the world.

After participating in an academic conference in Lima one January (deep cold winter in Ontario, midsummer in Peru), I traveled from Lima to the city of Cusco, high in the Andes mountains. The elevation of this ancient Incan community is so high that many people get altitude sickness when they arrive. It can take the body a few days to acclimatize to the lower levels of oxygen in the air, a process aided by drinking the completely legal and therapeutic coca leaf tea. After the requisite days of rest, I took the train to Machu Picchu, the ancient and mysterious ruins high in the Andes.

The train left the station very early in the morning while it was still dark. As our train pulled out of Cusco, it traveled for about five minutes, then stopped and returned to the station. Once back at the station, we stopped and headed off again in the same direction as we had the first time, only to stop again five minutes later and return to the station once more. It turns out that Cusco is surrounded by mountains with slopes that are too steep for trains to go straight up. So the train has to leave the city by zigzagging back and forth, each time on a different track, gradually gaining elevation, until finally it can leave the basin.

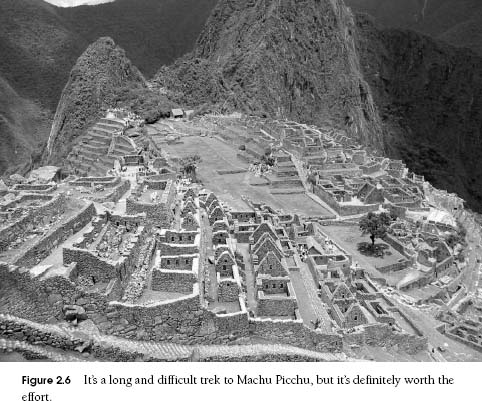

After a surprisingly long train ride, we disembarked in a small village and made our way to a waiting bus. The bus then crawled up the side of the mountain, switchback after switchback, each one offering a more magnificent view and more than a few sweaty palms. Finally, after a seemingly precarious ride, we arrived at the parking area. From there we hiked up some very steep paths until finally we emerged into the open and could see Machu Picchu at our feet. The view was magnificent. Even if there were no ruins there, it would be worth seeing the precipitous drops and tree-covered slopes (see figure 2.6).

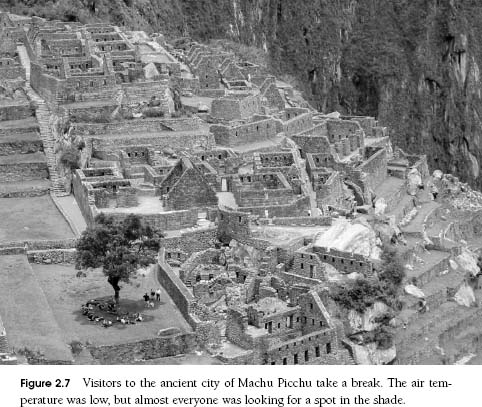

Machu Picchu is located near the equator, so you would expect it to be very hot, but because of the high elevation the air temperature does not get very high. Despite the fact that the air temperature hovered around 15°C (59°F) that day, however, people were not wearing jackets or sweaters. There was a large input of solar radiation, and after hiking around the ruins for a short while people began to seek out cooler places. At one point, after I had climbed high above the ruins, I looked down to see that almost everyone was in the shade of a single tree (see figure 2.7).

Despite being in one of the most magnificent and interesting landscapes on earth, and despite having made an arduous trip that would likely be once in a lifetime, people quit exploring the ruins and gravitated to the one spot on the site where the solar radiation load was reduced to a thermally comfortable level: under the tree. To me, this served as a powerful indication of the value of microclimate.

One of my graduate students, Nimmi, spent some time in India collecting data for her thesis. Not having been to India myself, I was very interested to hear what she had found out about how the locals deal with the intense heat in the middle of the dry season. One of the most poignant stories she told me was about people going to outdoor prayers in the heat of the day. Some days the temperature can reach 50°C (122°F) with full sun and no wind—a recipe for hyperthermia! Nimmi described the apparatus that had been set up to protect the worshippers. The first element was a series of bolts of thin white cloth hung horizontally overhead. This intercepted and reflected away much of the solar radiation before it reached the people. The second element was a series of overhead pipes with small nozzles on them that sprayed a very fine mist of water. Before the water reached the people, or perhaps just as it reached their skin, it evaporated. Water requires quite a large amount of energy to change states from liquid to gaseous form, and in this case it would take that energy either from the air or from the skin of the people. In either case, it provided a cooler environment. The air was being cooled, and the skin surfaces of the people were being cooled. The very dry air in India during the dry season allows for tremendous amounts of evaporative cooling to take place.

There has been much inadvertent modification of microclimates in history as well. Some of these changes might have contributed to the demise of some civilizations, and some of them we are only now attempting to address. A couple of big issues that remain to be resolved are urban heat islands and air pollution.

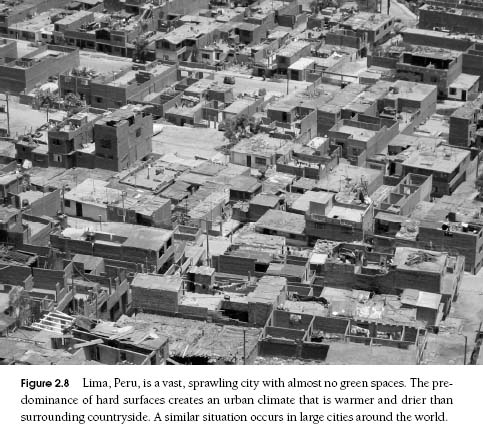

Cities tend to replace vegetated landscapes with concrete and asphalt—soft, moist, and green becomes hard, dry, and gray. The result is an urban core that is hotter and drier than the surrounding countryside and that has become known as an urban heat island. Some cities have very little urban vegetation (see figure 2.8) and can create situations where the air temperature in the core of the city is several degrees warmer than outside the city. This effect is most prevalent on clear evenings when natural areas have an opportunity to cool down but urban areas do not.

Another urban scourge is air pollution. Exhaust from vehicles, furnaces, power-generating plants, and manufacturing all contribute by spewing particles and gases, such as sulphur oxide, nitrogen oxide, and carbon monoxide, into the air. This causes problems ranging from damaged structures to health issues in the population. These problems are often experienced not in the area where the pollutants are generated but some distance downwind. Smog is often worse downwind from a city than it is in the city itself. It's a bit like living downstream from someone who insists on running their sewer into the waterway. They have little incentive to change since there is little personal consequence.

In one situation in Canada, air pollution from the nickel refinery in Sudbury was killing the local vegetation. The landscape was so devoid of life that NASA trained their astronauts there for going to the moon. The situation was resolved by building a much taller stack for the emissions, and the local environment around Sudbury has rebounded spectacularly. But all they really did was move the problem farther afield so that it no longer was Sudbury's problem. Now the emissions are being scattered downwind of the city and dispersed over a larger area.

Whether a landscape or a building modifies the microclimate in a positive or negative manner, there is much that it can teach us. Human creativity and ingenuity are boundless, and our ancestors were faced with living in some very challenging climatic conditions. Their creative solutions are slowly but surely disappearing and should be documented and studied before they go. There is probably an example near you that could be studied. Is there a very old house that was built before central heating and air-conditioning became popular? Maybe it has been built in a manner that minimizes the energy use. Maybe there is a shelterbelt of trees that protects it from the prevailing cold winds during winter. Maybe there is some enigmatic element in the house, like a hollow wall, or a stack with a scoop that you could investigate and figure out its purpose. Or maybe there is an abandoned apple orchard near your home. Maybe the location relative to the topography is interesting. What direction is the slope facing? Are there some trees still alive while others have died? Are there different varieties of apples in different parts of the orchard? These might be clues as to the micro climatic conditions. There are examples all around us, and all we need to do is to look for them.