3 / TOWARD A GENERAL THEORY OF MEDIA

There is no media theory.

—J. Baudrillard1

The previous reflections on the media concept should have shown three things. First, in all of the theories presented, the respective concept of the media played a prominent role. Except for McLuhan’s theory, which fashions itself as a media theory, the media concepts, however, largely owe this role to necessities of theory design. The media theories primarily have a subsidiary function within the framework of the antecedent theoretical intentions; hereby they take on a role that they cannot just shake off, for none of the theoreticians introduces the concept of the medium on the basis of a conceptually independent media theory.

Second, because of the lack of a general media theory with basic conceptual autonomy, the media concepts presented are so influenced by the characteristics of concrete, prototypically introduced media that in the course of their implementation theoretical frictions are established that are more suited to ensure the disavowal of the media concept than to secure it new theoretical attention. In order to develop a robust media concept, it thus appears to me to be necessary to take up the risky task of developing an independent media concept on the basis of fundamental principles; here the concept will not be acquired by generalizing characteristics of the concrete media (e.g., money, language, writing), for this procedure entails the risk that the specifics of such examples in each case will preform the concept that is to be developed in inappropriate ways, and where numerous paradigmatic media are used, a conglomerate of incompatible models may become the basis of media theory. In order to avert the danger of distorting the concept from the outset by systematically orienting it in reference to particularities or inner heterogeneity that tends to develop as methodological inconsistencies, a sufficiently general concept must be chosen as the basis of a conceptual definition of media. Where the conceptual language of a media concept cannot be tailored to specific media—and it thus serves to specify an individual medium—in order to be robust, that language must be so general that the specific individual media can be described by further specifying the general concept.

In my view, a further result of the previous chapter lies, third, in the diagnosis that media theories converge by assigning specific scopes of behavior. In each of the presented theories—and the theories converge in this—the media concept serves to characterize specific scopes of possibility that are available in the form of media. Parsons, Habermas, and Luhmann conceive of media as mechanisms that open up new possibilities for interaction against the background of the open, nonspecified horizon of language; they achieve this by limiting the scope of linguistic action coordination in their specific way. Through the exoneration of the risks of the action coordination, which arise due to the unlimited horizon of language, scopes of possibility emerge that can be understood as specifications (Parsons, Luhmann) or as specifications or substitutions (Habermas) of linguistic interactions. Also from the action-theoretic perspective in accord with which Dewey develops his media concept, media appear to be sets of specific possibilities for action, which Dewey obligates art to develop. And even McLuhan’s vaguer media concept achieves its diagnostic power solely against the background of media-dependent possibilities for perception and interaction.

In light of the convergence, finally a connection can be made out between the display of the scope of action that emerges in the framework of media-integrated interaction and the possibility for understanding actions and social processes against the background of these possibilities for action. Before a precise analysis of this connection can reap the rational-theoretic reward of a general media theory, first, we are faced with the task of developing the foundation for such a theory. The first section of this chapter is thus dedicated to the sober task of formulating elementary concepts of a media theory.

Bracketing the system-theoretical approach, the short version of the background thesis of the diagnosis of convergence is:

(M1) Every medium presents a specific number of possibilities for action that arise for the actors.

Before I begin the foundational conceptual work, however, I would like to clarify which theoretical perspective I think is capable of solving these conceptual groundwork problems. This perspective comes to light when a more basic dimension of the convergence thesis is viewed than the ability to propose a concept of medium that can serve as the lowest common denominator for the (intelligible) media concepts in their various theoretical contexts. If one more specifically calls to mind the implications of the convergence thesis, it soon becomes clear that the convergence thesis provides a metatheoretical diagnosis. It maintains that the media concept plays a central role in attempts to understand processes of social interaction. The thesis is not primarily supported by material kinship relationships that exist among the media concepts; rather, it views the function that the media concept has in the respective theories as something that connects the conceptions. The theoreticians introduce the concept of the medium in each case in order to facilitate the understanding of interaction processes as processes of understanding. With the help of the media concept, social interaction processes are intelligible as communication processes. The media concept makes it possible to describe forms of interactive behavior as forms of interactive action and indeed by means of the assumption that acting social individuals understand each other reciprocally as beings that choose behavior patterns (or sequences of behavior patterns) from a shared stock of types of behavior patterns.

Because chosen types of behavior patterns such as these owe their status as (proto-)actions to the interpretations of this behavior, the theoretical perspective that I use in the attempt to develop a basic concept of media theory is an interpretationist perspective; however, as I will show, it is a variation of interpretationism that considerably loosens its connection to the linguistic paradigm. The starting point for the development of media theory is, first, the assumption that the concept of the media plays a role in the attempt to understand those social interaction processes in which language plays no role at the surface level of the interaction. Hereby there is no principal difference between the role that the media concept plays for understanding in theoretical contexts and the role that the media play for those interacting in the social processes that are to be understood: just as the social theoreticians, from their interpretive perspectives, understand the observed interaction processes against the background of a hypothetical medium, so too, those interacting socially understand the behavior of their counterparts as actions against the background of assumed behavioral alternatives, that is, against the background of medial possibilities.

If I attempt to develop media theory as an independent theory in what follows, then, in light of the interpretationist perspective, this attempt must assume a form in which it is possible to show the plausibility of increasingly decoupling understanding from language. If one begins with the familiar concept of radical interpretation in which an interpreter correlates expressions in an object language with metalinguistically articulated truth conditions and in this way formulates empirically testable T-theorems, then a procedure emerges that successively reduces the linguistic preconditions for radical interpretations so that each theoretical element that the foundational vocabulary of an independent media theory must relate to can be identified. I attempt to achieve this process in three steps:

1. In the first step I confront interpreters who are fully able to use language with nonlinguistic expressions of producers who are able to use language. In order to do this, I will revisit the context in which Dewey developed his view of media—that is, the context of communication at the level of aesthetic experience—and investigate the understanding of nonlinguistic expressions that we commonly refer to as works of art. Here I am above all concerned with showing that the understanding of works of art can be viewed as an exemplary case of the understanding of nonlinguistic expressions. Under observance of an important and in my view rightly widespread intuition, namely, the view that works of art cannot be translated linguistically, this can nevertheless be reconstructed with the tools of media theory as a genuine case of understanding, and indeed as a case of radical interpretation in which the interpreter makes use of hypothetically assumed media. Within the framework of this scenario I start with the familiar assumption: I examine a case in which art is understood and in which both the interpreter and the one that is supposed to be interpreted can use a natural language. The goal of my analysis is to show that media play a mostly unarticulated role in the interpreter’s interpretation language, but also in the aesthetic production of those who are supposed to be interpreted (pp. 143–220).

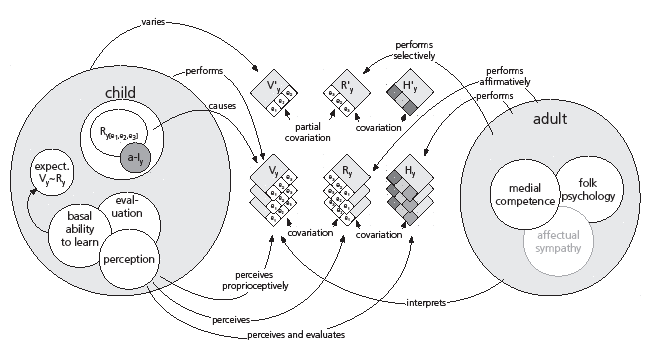

2. In the second step I want to further loosen the linguistically bound prerequisites of the first scenario by assuming a more radical situation of interpretation, a situation in which it is not clear whether those who are supposed to be interpreted even speak a language. For this purpose, I introduce a situation from field research in which two competing interpreters who are able to use a fully developed interpretive language investigate members of a fictitious ethnicity in order to find out whether those being interpreted even speak a language and which of their observable means of behavior are linguistic or nonlinguistic (perhaps artistic) expressions. In the framework of this scenario it is not only presupposed that those being interpreted do not use a language for those expressions that the interpreters are trying to understand, but it is even imagined that those being interpreted may not speak any language whatsoever. The goal of the investigation at this level is to specify the role of the media concept against the background of the problem of providing a suitable conceptual reconstruction of a situation in which the interpretation of beings who do not speak a language is carried out by interpreters who do speak one (pp. 220–233).

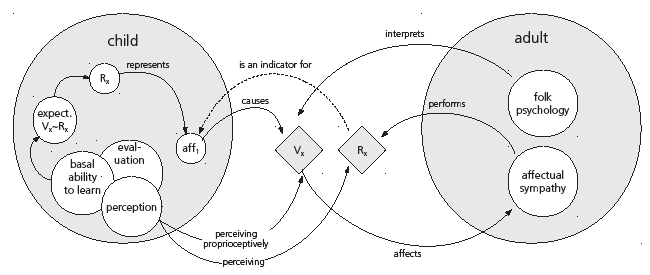

3. In the third step, a level should finally be reached from which we investigate interactions between beings who we presume do not use anything that we would call a language, but whom we nevertheless view as beings that communicate with one another. The question that is to be raised here is whether the tools of media theory are able to characterize a level of sublinguistic communication that can be understood as an evolutionary–theoretic link between the level of completely developed linguistic communication and mere causal interaction processes. In the framework of this scenario, media theory has to prove that it is able to avoid the circular implications of the established interpretationism; for with a view to the question of how the primacy of the interpretation for the development of language, meaning, and mind can be reconciled to assumptions of evolutionary theory, interpretationism appeases itself with the answer that all speaking beings have parents, consequently parents that possess an interpretation language. However, this raises the question whether we should assume that in the evolutionary history of humans, which must include a transition from a species that does not speak a natural language to humans who do speak one, there were parents who—in contradiction to the interpretationistic assumption—by virtue of their genetic disposition, were interpreters of their children. On the other hand, it is not easy to see how this transition can be construed as gradual, because the rationality that is imputed by the interpreters has a constitutive all-or-nothing character that eludes reconstruction as something that can become established gradually (pp. 233–240).

In contrast to Parsons and Habermas, I thus do not attempt to develop the media concept in a social context in which a language is present as a medium from the outset, which social actors can use to make agreements—for example, to treat something as money—in order, in this way, to institutionalize media, whose specific behavioral possibilities may indeed facilitate special economic forms of interaction, but that in principle do not go beyond the linguistically individualizable behavioral possibilities. In the framework of the outlined three-step process, I would like rather to show that media can be understood as sets of behavioral possibilities that do not necessarily depend on the individuating power of language.

3.2. AN INTERPRETATIONISM EXPANDED BY MEDIA THEORY

3.2.1. What Does It Mean to Understand a Work of Art?

As a first step toward expanding interpretationism with the aid of media theory, I want to show the plausibility of the view that artistic media provide behavioral possibilities, which, under certain conditions, can also serve as possible ways of individuating thoughts that cannot be individuated by means of language. Setting out from basic and widespread intuitions regarding that which is expressed by works of art, I want to show how the resources of media theory allow us to develop a view of the production of works of art and their interpretive reception that makes it possible to rationally reconstruct these intuitions. In doing this, I will attempt to develop a vocabulary of media theory, in debate with the genuine nonlinguistic, communicative forms of art, that is nonetheless sufficiently general to allow the apprehension of nonlinguistic forms of communication beyond the domain of art.

3.2.1.1. Difficulties with Intuitions

In developing our own interpretationist perspective with a view to the understanding of works of art, we are confronted with the following difficulty: the established interpretationism, which is influenced by Davidson, conceives of understanding as a process in which we correlate the statements that are to be interpreted with (metalinguistic) sentences. However, insofar as these interpreting sentences are metalinguistic, a linguistic structure is read into what is interpreted; it is initially at least questionable whether, with a view to the understanding of nonlinguistic works of art, this consequence is appropriate. For besides the theoretical questions regarding whether works of art possess a predicative structure and which role the concept of truth plays in connection with the understanding of works of art, it is not clear how an interpretationist theory can accommodate the intuition that works of art articulate thoughts that cannot be linguistically articulated.2

Yet, if with regard to this difficulty, we bear in mind, for example, the basic models that we employ to speak about music,3 then it is apparent that the model of language exercises an enormous influence even on those artists and theoreticians who insist on the irreducibility of music as an independent form of expression. Strangely, these advocates of the autonomy of musical expression often fail to elude the analogy between music and language; thus, they are forced to take refuge in paradoxical formulations that maintain the independence of music from language precisely with the help of the analogy of language. For example, in addressing the question “What is music?” in 1932 Anton Webern answered:

Music is language. A human being wants to express ideas in this language, but not ideas that can be translated into concepts—musical ideas.4

Like Webern, Adorno is also convinced that music is based on a form of quasi-linguistic thinking, which however cannot be transcribed into language; but Adorno does not want to allow the analogy between music and language without further ado. Because language is also the medium of a subsuming form of thinking, a form of violence that Adorno had traced back to the fibers of conceptuality, music is not to be an accomplice to it. Yet, because he cannot bring himself to abandon the language analogy, he must attempt to state the putative linguistic character of music and its (simultaneous) distance from language paradoxically: “It is by distancing itself from language that its resemblance to language finds its fulfillment.”5 A glance at a dictum of Eduard Hanslick, who is associated with the autonomy of music like no other, clearly indicates that it is not first in the twentieth century that music is deemed a language. Hanslick writes:

Music has sense and logic—but musical sense and logic. It is a language which we speak and understand yet cannot translate.6

Whatever allure the formulations of Adorno, Webern, and Hanslick may appear to have on a cursory reading, the notion of an untranslatable language raises the suspicion that, in the end, the formulations are attractive solely by virtue of their unintelligibility. For, does it make any sense whatsoever to speak of something as a language if what is supposed to be expressed with its help is not translatable into another language? On the contrary, isn’t it basic to our view of languages that they can be translated into one another? Can we view sounds that members of a culture that is foreign—for us—exchange among one another as a language without at the same time believing that they are in principle translatable into our language?7

The attempt to follow the intuition that music is an expression of an independent form of thought (and to that extent requires an independent concept of understanding) by trying to secure the independence of music through the employment of the analogy of language appears to me to result in one of two equally unattractive consequences: either we compromise our concept of language by allowing untranslatable languages (music being among them) or we understand music—in flagrant contradiction to the intuition that it is independent—as a type of deficient language, the status of which can only be clarified by relying on the earlier dignity of language. Even if the analogy to language is inappropriate and, in the cited texts, appears rather inept at plausibly showing the independence of music, the intuition that it is supposed to help express is still clear:

(I1) Like language, music (along with other arts) provides a resource with the help of which it is possible to articulate (musical) thoughts;

a. consequently it is appropriate to believe that we can understand musical works of art; and

b. if we understand musical works of art, then we understand thoughts that cannot be expressed in language.

This intuition (I1) expresses to a certain extent that music is not an instrument that, solely on the basis of our knowledge of the human organism, is applied to produce causally describable effects. (I1) does not view music as a (legal) drug or psychopharmaceutical, and it insists that music has nothing to do with either Kant’s8 or Dr. Rueger’s9 medicine chest, because the mere pharmacological use sterilizes its capacities for interpretation.10

On the other hand, despite the capacity of music to articulate thoughts, it is not a language, for music has no predicative structure, and the endeavor to develop a grammar of music on the basis of an analogy to Chomsky’s generative grammar, such as Lerdahl and Jackendoff have attempted, creates many more problems than it is able to solve.11

3.2.1.2. Works of Art as Products of Ordinary Action

The scarcely plausible consequence of reading a linguistic structure into nonlinguistic works of art can indeed be avoided within the framework of interpretationism, but only at a price: works of art are understood against the pattern of common instrumental explanations of action, and (hereby) as actions or consequences of actions that actors have carried out because they believe that the works of art are appropriate means for achieving certain (for example, expressive) goals. An analysis of this sort does not in fact structure the work of art as a linguistic expression, but it ascribes thoughts to the producers of works of art—specifically, beliefs and preferences—that exhibit the common structure of thoughts composed by language and that present the reasons for the production of the works of art. According to this perspective, understanding a work of art thus consists in nothing but identifying those beliefs and intentions that allow us to rationalize the production of a work of art.

An instrumentalist analysis of artistic action, however, clashes with the further widespread intuition that artistic action concerns a special form of intentionality. According to this intuition, artistic intuitions are indeed intentional in the sense that works of art are not involuntary expressions; but they are not expressions of intentions that those who create them have independently of works of art. (I2) attempts to articulate some of the motifs that lie behind this often only vaguely formulated intuition.

(I2) Works of art are intentional products of those who produce them, but:

a. The type of intentionality does not appropriately come into purview if works of art are merely understood as instruments for realizing the intentions of those who produce them; for in some way unintentionality and happenstance play a role in the production of works of art.

b. A work of art is not adequately understood if we can say “what the artist wanted to say with its help”; understanding works of art does not consist in identifying the intentions that the artist may have had. In any case, this does not exhaust it.

c. If we could say without reservation what a work of art is supposed to express, then we would not need the specific form of the work of art in order to articulate what the work of art does express. Works of art are forms of expression of thoughts that require the specific form of the respective work of art for their individuation. That is the reason works of art are not related to intentions the way means are related to ends.

(I2) insists that works of art are indeed intentional products, but they cannot be understood according to the model used to rationalize common behavior. However, insofar as my analysis is based on an action-theoretic perspective for analyzing nonlinguistic communicative acts, the systematic problem consists in developing an understanding of such acts that is able to accommodate the mentioned intuitions. Before taking this up, however, I would like to clearly explicate the difficulties that arise if works of art are understood in accord with the common action-theoretic perspective.

In adopting the action-theoretic perspective that I have accepted in developing a media theory, one runs up against a problem: how is it possible to introduce a concept of medial action without making media theory conceptually dependent on the general analysis of action? This is problematic because the standard general theory of action conjoins actions with propositional attitudes; so in using the model to explain media theory, it appears to make the possibility of (medial) action dependent on the speech competencies of the actors. In attempting to characterize medial action as a genuine form of action, the media theory being developed here is not just an affront to system theory, but it also stands in a strained relationship to the standard analysis of action, which casts action in terms of propositional attitudes.

If, with the help of the standard analysis, we view a behavior as an action, then we start with a description of the behavior that uses intentional vocabulary, i.e., we position the observable behavior of a person P (a) in relation to her mental conditions, (b) in relation to some meaning that the activities of P have for P, and (c) in relation to the observable consequences of the activities that P performs. The practical syllogism integrates these three presuppositions of an intentional explanation in the form of an argument in which (a) and (b) function as premises and (c) as the conclusion:

(H1)

a. P intends to achieve Y;

b. P believes that X is a means to achieving Y;

c. (ergo) P does X.12

In the context of my reflections, two problems are connected with (H1). For one, (H1) is not suited for the analysis of artistic action because it is irreconcilable with intuition (I2); for another, (H1) poses a metatheoretical problem, for the problem that arises with a view to the independence of the basic concepts of media theory consists in the fact that, in accord with the perspective of the linguistic turn, intentions and beliefs must be described as propositional attitudes, thus the concept of action is made conditional on the existence of the actors’ propositional attitudes.13 However, were we to proceed from such a conception of action, then the main reason for developing the media concept here—namely, to contribute to a concept of understanding and rationality that is not based exclusively on language—would be illegitimate from the outset; for the basic motivation for incorporating media theory into the debate on the conception of rationality as a possible fundament consists precisely in expanding that fundament beyond language.

If, in order to sketch out a concept of action that brings us closer to solving both the problem of the specific intentionality of artistic action and the metatheoretical problem, we now attempt to show that it is plausible to develop a concept of action that does not entail constitutive linguistic presuppositions, then two strategies emerge. For one, it is questionable whether the fact that intentions and desires assume the form of propositions in intentional explanations necessarily means that the intentions and desires of the actor must be present as propositions. In line with this strategy, it would have to be claimed that the rationalizing interpretation of the behavior of individuals works with ascriptions that, as linguistically articulated, can only assume the form of propositions, but this does not allow any inferences about the form in which actors represent intentions and desires. In any case, I question whether it is promising to give much weight to an argument that emphasizes the “artifact character” of linguistic reconstruction that a rationalization from the perspective of an interpreter inevitably adopts, because it is not clear how strong a potential difference there is between the form of external rationalizations, on the one hand, and the internal conditions of action, on the other. Within the framework of this strategy, it is still a problem, for example, to explain how the actor, from his or her internal perspective, is supposed to be in a position to individuate different intentions and beliefs without being able to refer back to a medium for individuating the constituents of action, thus intentional states.

Within the framework of a second strategy, I would thus like to attempt to show that there are actions that are not connected with the existence of the actors’ propositional attitudes, but that can be understood with the help of the assumption that there are other media besides language that allow the ascription of intentions. To begin with, the view that the existence of intentions is fundamental for action is not controversial. However, it is characteristic for a position that strictly adheres to the linguistic turn that the intention that the actors link to their action is dependent on an ability of the actor, namely to articulate it (at least potentially) in a sentence like: “I desire p,” or “I believe p,” and so on. So this second strategy attempts to loosen up the tight connection between intentionality and language. In a first step (1) I will initially attempt to screen the arguments, above all developed by Davidson, that intentionality is dependent on language. In a second step (2) I will contrast these arguments with Searle’s reconstruction of the connection between intentionality and language; because this reconstruction depicts intentionality as a more basic phenomenon than language, it may be able to contribute to solving the two mentioned problems. On the basis of the various difficulties in Davidson’s and Searle’s positions, I will attempt in two further steps (3) to refine the view of intentionality and (4) to specify the idea of an expanded form of interpretationism.

1. LANGUAGE AS A CONDITION FOR INTENTIONALITY

In the arguments that are meant to support the thesis that intentionality is dependent on language, language plays the role of an instrument for individuating intentional states, which are only able to acquire identity within a network of other intentional states, a network whose inferential relations can only be determined by language. In an interpretationist perspective such as Davidson’s, in ascribing intentional states, language functions initially as nothing more than a behavioral pattern that is sufficiently complex to allow the correct inferences to the propositional attitudes of the speaker as long as there is sufficient information about the behavior and which actions are possible.14 Language thus presents itself as a behavioral pattern, the interpretation of which enables us to make inferences regarding how propositional attitudes can be individuated in a (necessarily) largely coherent network of logical relations. We can thus ascribe the propositional attitudes to the being whose behavior we want to interpret. Certainly, for Davidson this analysis does not have the character of a conclusive argument, with the help of which it can be shown that intentional attitudes are dependent on the possession of language. In order to provide such an argument, it would have to be shown that language is the only possible medium for a sufficiently complex behavioral pattern. Because Davidson is in fact convinced that this interrelation is correct,15 but he cannot prove it to be necessary, the thesis that there is no alternative to language being the medium for individuating intentional attitudes must continue to be viewed as an assumption.

The interpretationist perspective must now, however, face the fact that we, as interpreters, also manage to successfully explain and predict the behavior of nonspeaking animals by, in some manner, ascribing beliefs, desires, and intentions to them. However, because the reason for making allegations of this sort is not mere fad, but because we lack really good alternatives, the thesis of language dependence suffers a further loss of plausibility for the time being. However, Davidson’s cited article contains a further and weightier argument for the dependence of intentionality on speech.

On the basis of the holistic assumption that all propositional attitudes (and thus intentions) are dependent on a network of beliefs, Davidson claims that only beings with a concept of belief can have beliefs and that only those beings with a language can have a concept of a belief.16 If we accept that beliefs are a fundamental condition for the possibility of intentions, then, following Davidson, we must also accept that only a being that can refer to the fact that it believes p—that is, that can form second-order beliefs—can develop beliefs about anything at all. For only if a being can draw a distinction between (subjective) beliefs and objective truth with the aid of second-order beliefs does it make any sense to ascribe an ability to have beliefs to this being. From the interpretationist perspective, however, we can only ascribe this ability to a being if we can interpret its behavior in the context of linguistic communication such that it masters the difference between subjective belief and objective truth. In short, only those beings that are able to contrast their subjective beliefs with others’ beliefs in an intersubjective speech practice, and in doing so refer to something like an intersubjective truth, have the ability to refer to their own beliefs.17

This argument seems much stronger than the earlier one if we can preclude that, on the basis of the assumption that all propositional attitudes are dependent on a context of believing, it begs the question by implying from the outset that the scope of possibilities only includes linguistic entities. Yet, it seems to me to be a stronger claim that all mental states that are relevant for acting depend on states whose propositional equivalents are capable of being true. In other words, it is plausible to maintain that the ability to have beliefs is necessarily dependent on the concept of belief, a concept that can only be had by one who possesses a language. But, in order to be able to have a thought, is it also necessary to have a concept of a thought? Indeed, according to Davidson, all propositional attitudes are thoughts, but are all thoughts also propositional attitudes?

So, even Davidson’s second, stronger argument is only a conclusive argument for the dependence of intentionality on language if it can be shown that a concept of intersubjective truth is the only possible way to establish the difference between subjective believing and objective validity, and that it thus presents the only possibility for second-order thoughts. However, a vigorous reconstruction of the argument provides important indications of how the thesis of language dependence can be contested. For as far as I can tell, it leaves only two options: either it can be shown that intentionality always has to be presupposed in order to explain how something like a language can develop (section 2), or it can be successfully shown that the concept of second-order thoughts is not tied to language (section 3). Within the framework of the second strategy it is necessary to show that the concept of second-order thoughts can also be introduced with a view to non-truth-conditional intentional attitudes; consequently, beliefs cannot be necessary conditions for actions.

2. INTENTIONALITY AS THE BASIS OF LANGUAGE

A prominent position that denies a necessary connection between the existence of propositional attitudes and actions is the naturalistic conception that John Searle presents in his work Intentionality.18 According to Searle, actions are not connected to existing propositional attitudes but to “intentional states,” which, for their part, are prelinguistic. Searle thus reverses the relationship between intentionality and language proposed by the propositionalists: “Language is derived from Intentionality and not conversely.”19 Searle shows that we must presuppose intentionality as a basic phenomenon in order to explain that mind is able to “impose intentionality on entities that are not intrinsically intentional”20 by ensuring that these entities deal with something or are related to something. In other words: if mind can relate entities that are not in themselves intentional to something—if, for example, it can use them for purposes of representation—then intentionality cannot be explained with recourse to relations between these entities but is the basis of the possibility of such relations.

In the evolutionary theoretic framework in which Searle develops his theory, it is clear that language must be reconstructed as a late product of evolution on the basis of species competencies. But independently of the evolutionary-theoretic perspective, which, on the basis of prelinguistic forms of intentionality, explains what would be necessary for the development of language,21 Searle explicitly maintains the logical primacy of intentionality before language because “certain fundamental semantic notions such as meaning are analyzable in terms of even more fundamental psychological notions such as belief, desire, and intention.”22 With recourse to these “more primitive” forms of intentionality, which possess an intrinsic relationship to conditions of satisfaction, it is possible to explain how entities that do not have their own intrinsic intentionality are taken up in the service of mind. The intrinsic relationship of primitive intentional states to conditions of satisfaction is, in a manner of speaking, the model that is broadened in the development of language, imposing the same conditions of satisfaction on a speech act as those that the mental state has that is to be expressed with the utterance in the speech act.23

It is clear that this concept entails a series of problems, problems that are primarily a result of the inverted relationship between language and intentionality. For it is of course questionable whether a being can draw on one of its intentional states without identifying this state with the means by which it draws on the state. However, it remains an open question whether language is the only means that can assume this function.

Searle appears to think the following idea can serve as a solution to the problem of individuation: while a verificationist theory of meaning only has truth-functional propositions at its disposal with which to individuate beliefs as elements of a network that facilitates the individuation of intentions, Searle attempts to individuate the intentional states directly with reference to conditions of satisfaction. Accordingly, an intentional state is a state that is characterized by states of affairs in the world that correspond to its satisfaction. That implies that for “any intentional state with a direction of fit, a being that has that state must be able to distinguish the satisfaction from the frustration of that state,”24 and we must assume that this differentiation is possible without language if we want to maintain the primacy of intentionality over language. Otherwise Searle’s meaning-theoretic program, which he clearly sketches out in the following lines, would be pointless.

The fact that the conditions of satisfaction of the expressed intentional state and the conditions of satisfaction of the speech act are identical suggests that the key to the problem of meaning is to see that in the performance of the speech act the mind intentionally imposes the same conditions of satisfaction on the physical expression of the expressed mental state, as the mental state has itself.25

The attempt to contrast the propositional reconstruction of intentionality with a naturalistic perspective in the interpretation suggested here leaves us initially with a tattered view: from a propositionalist perspective it cannot be clearly shown how we end up with a situation in which there are beings that make intentional use of non-intrinsic-intentional entities if intentions can only be identified by means of such entities; from the naturalistic-intentional perspective, it remains questionable how mind can draw on its intentional states if it lacks the means that can only be generated if individuated intentional states are already presumed.

3. TWO FORMS OF INTENTIONALITY

However, a productive way out of this dilemma does seem to me to be possible if we differentiate at least two forms of intentionality, one that I initially only characterize negatively and describe as a form dependent on language and one linguistically independent form.

Setting out from the broad interpretation that Searle gives to his view of intentionality—namely, to characterize those mental states that are about something or that are directed toward something as intentional states—for the time being, it appears to be neither counterintuitive nor problematic, for example, to ascribe intentional states to small children, who do not yet speak a (propositionally refined) language. Nor does there appear to be a problem with sufficiently individuating these states: in a situation in which a small child stretches his hand out toward an object x, which is in close spatial proximity to a second object y, we are hardly surprised if handing the child x is noted with satisfaction, while handing the child y is protested loudly. In such cases we do not ask how it was possible for the child to find itself in a certain intentional state, but we assume that the child has access to criteria for the conditions of satisfaction of the intentional state that it has, and is thus able to differentiate this intentional state from others without being able to speak a language. So I do not see a problem in initially following Searle and presuming an elementary form of intentionality (which I would like to call A-intentionality), with states that are sufficiently individuated without language.26

However, it is questionable whether the child can also behave with reference to the intentional state in which it, according to this analysis, finds itself. In other words, it is questionable whether the child chose the state or could choose it, or whether the A-intentional state befalls the child. It is reasonable to assume with Davidson that the possibility of choosing intentional states or of intentionally individuating such states is connected to the ability to draw on these states with the help of a medium like language. A theory of developed intentionality, understood in this way, would now have to show which conditions have to be fulfilled in order, on the basis of A-intentionality, to allow the determination of the competencies and instruments that are needed to develop higher-level intentionality, which includes the possibility of being able to (arbitrarily) produce intentional states.27

In view of these thoughts, a preliminary criterion for A-intentional states could, for example, be as follows:

(A1) A mental state Ia of a being B is an A-intentional state if and only if

a. through Ia, B is disposed to differentially respond to its environment; and

b. Ia is individuated in a way (e.g., causally) that precludes it from being steered by B as long as B only has A-intentional states; and

c. the identity of Ia, i.e., the content of Ia, is determined as long as the conditions of satisfaction of Ia are sensuously present to B.

Ascribing A-intentional states is legitimized from the viewpoint of an interpreter if the interpreter’s explanation of the behavior must assume that the being that is to be interpreted (B) possesses nonlinguistic representations of existing and not-existing states of affairs, and these representations steer the being’s activity. Thus, among the linguistically independent states, these states are the ones that we ascribe to beings because we can only plausibly explain their behavior by maintaining that they are able to differentiate states of affairs in reference to whether they are conditions of satisfaction for their intentional states or not. Here, however, A-intentional states are intrinsically intentional. They are not intentional by virtue of being self-interpretations. They have content that does not require an interpretation in order to be individuated. Instead, in the context of environmental conditions, it requires a functional role.28 A-intentional states are thus states that befall the being that has them. We must assume that beings with A-intentional states possess a representational machinery that is indeed able to produce representations from states of affairs, but that does not produce representations of such representations. A being whose most developed mental states are A-intentional states thus does not possess the ability to refer to these states; for the content of A-intentional states is never another intentional state. Along with Dretske and Millikan, one can suppose that A-intentional states function to show something, be it inner states or states of affairs, but the fact that a being, because of its history of interaction with its social environment, makes use of suitable means does not result from knowledge that these means are suitable, a knowledge that would be accessible to the being as explicit knowledge. Rather, it is warranted by functional mechanisms. If a being finds itself in an A-intentional state, Ia1, there are no reasons for the change to a state Ia2, but only causes. Here it is not precluded that these causes play a weak normative role that can be completely explained with functionalist concepts, and that have something of the status of needs. In that, A-intentional states occupy a position between those mental states that we call perceptions and those mental states that we call thoughts. Like perceptions, they have an intrinsic relationship to content that we can imagine being conveyed via functional mechanisms; like thoughts, they are individuated in normative relations, however, in normative relations that can be completely naturalized.

But even if one accepts this characterization of basic intentional states and in doing so agrees with Searle insofar as one is ready to accept that there is a foundational level of intentionality that is independent of language, it is clear that, on the basis of intrinsic intentionality, complex phenomena like artistic action cannot be reconstructed. For artists work precisely against the background of alternatives that are alternatives for them; in a way that is to be more precisely explained, they have reasons for developing a work of art in one way and not another.29

If one wants to accommodate this fact in a theoretically suitable manner—that means in a way that makes it possible to maintain intuitions (I1) and (I2)—then it is necessary to provide a reconstruction of higher-level intentionality that does not imply that this higher-level intentionality can only be achieved if beings acquire linguistic competencies. The higher-level form of intentionality must rather be construed such that the ability of a being to relate to its own mental states becomes plausible; here one can assume that Davidson’s demand for a second-order concept indicates the specific form by which the higher-level intentional states are reached by linguistic means. Intentional states that are independent of specific linguistic means must thus be characterized as second-order intentional states; because of this attribute, they can be actively adopted. In order to be higher-level intentional states, mental states that can fulfill this demand thus must certainly fulfill the following criteria:

(HI) A mental state Ih of a being B is a higher-level intentional state if and only if

1. Ih is individuated in such a way that it can be steered by B; and

2. the identity of Ih, i.e., the content of Ih, is determined as long as

a. B draws on an A-intentional state with the help of Ih; or

b. B assigns Ih a position in a network of higher-level intentional states, some of which refer to A-intentional states.

Schema (HI) expresses in a very general form what we think of thoughts; thoughts are products of thinking. Thinking is (in any case, largely) a conscious, active activity; its products have an identity because of the fact that they are related to inner representations or stand in certain relations to other thoughts.

If we provisionally accept that Searle’s suspicion is correct, i.e., that the concept of meaning can be analyzed in more basic psychological concepts like the concept of desire, and we adopt this analysis for the construction of the level of A-intentionality, then we are faced with a problem, namely, of how to make the transition from the level of a causal reconstruction on the level of A-intentionality to the level of reasons that integrate the sphere of higher-level intentionality. If it is appropriate to speak of two levels of intentionality, and we assume that only the basic one is a biological phenomenon, then how, precisely, do the two levels connect, and how can we explain the transition between them that linguistic beings have obviously achieved? In principle, the way that I initially imagine this is as follows.30

In the above-described situation, the child finds itself in an A-intentional state (Ia[have x]), which is related to the possession of an object x; here the state is indicated by the outstretched arm and the noises the child produces. The desire that we, from the interpreter’s perspective, ascribe to the child is fulfilled if the child, for example, can put x in its mouth. If we assume that the child in the situation interacts with people who possess a form of language, and that in situations like those above accompany the passing of x or y with gestures and noises that the child itself can produce, then the child can correlate his A-intentional state with these activities and adapt these as instruments to articulate desires. The A-intentional state is hereby broadened to include a linguistic behavior that, in a benevolent social environment, serves as a relatively successful instrument for satisfying desires. For the construction of the higher-level intentionality, it is important that the linguistic activity (“x”) does not belong to the conditions of satisfaction of the A-intentional desire. Because the expression “x” has an instrumental character, and does not intrinsically satisfy the desire, it can be used for a correlation that can exist alongside the world-to-world direction of fit of the articulated desire: an inner-world-to-world direction of fit. If, in conformity with Searle’s theory of meaning, we at least assume that “x” can be provided with the same conditions of satisfaction as the A-intentional state, then “x” can be placed in a double correlation, namely, one to empirically having-x, and one to the desire to have x (Ia[have x]).

Among the obvious preconditions for expanding A-intentional states via intrinsically non-desire-fulfilling occurrences are the interpreters of the behavior of a child, who continually form hypotheses about which intentional state the child is now in. Another precondition is the sufficient constancy of those linguistic occurrences that the child is supposed to link to its respective states; those occurrences must be sufficient for the child and allow frequently correct ascriptions of its intentional states. If these preconditions are fulfilled, we can assume that the child will stabilize a number of relations between A-intentional states, acts of articulation, and desire fulfillment (Ia[have x] ↔ “x” ↔ having-x, Ia[have y] ↔ “y” ↔ having-y, etc.).

In order to plausibly develop higher-level intentionality, it is now imperative that the child not only brings the acts of articulation into an (instrumental) relation to its A-intentions, but also—as noted—that the interpreters react with sufficient constancy to expressions of “x,” as if the intention exists, Ia(have x). By virtue of the fact that the interpreters hold constant the relation between relata 2 and 3, they offer the child the possibility to observe the relations of the first two relata based on the expression. What exactly does that mean?

By expanding the relation between A-intentional states and their conditions of satisfaction to include nonintrinsic desire-fulfilling activities, an element is introduced to this relation that is sufficient for A-intentionality, which, since this is aimed at satisfying desire, initially has a primarily instrumental character. From the perspective of the interpreters, however, it takes on the character of a (quite reliable) indication of the existence of certain intentional states. If we assume that children expand their articulations spontaneously by varying or combining modifications, and we further assume that in the social environment of children, certain of these expressions are taken as an occasion to treat children as if they had intentions that correspond to the interpretations of expressions by adults, then the relations are stabilized between varied expressions and the states of affairs that the social environment brings about in reaction to the expressions. Because children behave in a manner that indicates they evaluate these states of affairs, as described above, one can assume that they balance these with their A-intentional intentions.

If we now expand the possibilities for expression so that the children’s practices of varying articulations are subject to limitations by virtue of the fact that the adults only accept a subset of the variants, and in this way something like rules of composition are stabilized, then a plausible case can be made that, with dependency on the differentiation of the levels of articulation, the ascription of refined intentional states becomes possible. Now, if expressions, by virtue of their interpretation in a social environment, lead to children being treated as if they had the intention that the interpretation is based on, then any expression of a person that fulfills criteria that are to be more precisely explained can also come to indicate the corresponding intentional state of that person. However, the person does not have this intentional state in the same way as she has an A-intentional state. For people who can achieve that scope of the medium of articulation which is able to be linked to an established practice of interpretation can individuate intentional states that they do not simply adapt, but that they in a certain sense create. But how?

I initially assume that at the level of articulation another form of contingency is possible than at the level of A-intentional states, one that arises from the compositional structure of the articulation. Here nothing more is meant than that the tokens of the established practice of articulation can be described as composites of a finite number of articulation types. Further, I assume that the interpretation practice achieves this contingency for the level of ascribed intentional states as the interpreters ascribe intentional states to the articulating individuals; here the degree of differentiation is correlated with that of the expression, and the person is treated in accordance with this interpretation. With a view to the person being interpreted, I assume, third, that the person learns to understand her own (spontaneous) articulations by the interpretation practices of others; that means she learns to understand them as a symptom of an intentional state that she herself has (in agreement with the interpretation practices of others). To the degree to which the articulation practice is oriented on experiences of ascribing intentions, the medium of articulation becomes a medium for individuating intentional states, which the articulating person learns to ascribe to herself. Here, A-intentional states take on the function of a screen, against the background of which the higher-level intentional states gain relevance as compatible or incompatible with the A-intentional states.

Higher-level intentional states are then, however, only able to be individuated through the differentiations that are possible in the medium of the expression. The medium in which this differentiation is made becomes an apriority of intentional states, which can only be individuated with its help. It thus holds for higher-level intentions that they are dependent on social media, because they are dependent on the possibilities that such media offer for ascribing intentions. If one accepts this analysis, then the development of a world of higher-level intentions fully accords with Davidson’s assumption that having or ascribing (certain) intentional states is dependent on the potential for differentiation of the medium on which the complex behavior that the interpreter interprets is based.

The solution that is proposed here, which sets out from Searlean starting points, finds its way to Davidsonian consequences, and needs to be further worked out, shifts the problem regarding the priority of language or intentionality to the problem of showing the plausibility of the transition between these two forms of intentionality. However, this problem might be solved if we introduce a social practice of interpretation, which I, for the time being, assume here.31 It remains open—and that is a desired consequence of my deliberations—whether a higher-level intentional state can only be identified by linguistic means, as the example of language acquisition seems to suggest, or whether other, nonlinguistic means could also assume this function. Before exploring this, however, it should be determined whether Searle’s naturalist theory of intentionality—which I have thus far drawn on only as a theoretical background in the reconstruction of the fundamental level of intentionality—might not also be suited to allow a reconstruction of higher-level intentionality of which we understand art to be an expression.

4. DOES SEARLE’S THEORY ALLOW US TO UNDERSTAND ART?

In the previous reflections I have attempted to show that it is plausible to use Searle’s naturalist interpretation of intentionality as a starting point for the development of a form of intentionality, which, in accord with Davidson’s postulates, is dependent on the fact that beings that develop this form of intentionality appropriate a repertoire of refined articulation possibilities in a social context. Here, however, it remains an open question whether Searle’s theory might not even provide the means with the help of which we could come to an understanding of art that harmonizes with our intuitions. After all, Searle’s theory promises to decouple language and intentionality, since language is not a condition or a prerequisite for intentionality. Nonlinguistic forms of expression like art, one might surmise, must then exist in a relationship to the underlying intentionality, which is analogous to linguistic utterances, and it must be possible to reconstruct them independently of language, i.e., as genuine intentional phenomena at the level of conditions of satisfaction.

In order to check this, I would like to turn back to the problem described above, namely, the problem of understanding works of art as products of ordinary action. If “understanding an activity as an action” simply means “describing an activity as intentional,” then, if one wants to retain this schema for artistic action, it is necessary to identify intentional states that are supposed to be the reasons for the action that is to be explained. In applying a rationalization of action to artistic actions, it would then be necessary to assume something like the following form, as a modification of (H1):

(H1.1)

a. P intends to express Y.

b. P believes that K is a means to express Y.

c. Therefore, P produces K.32

If we attempt to link (H1.1) to the above reconstruction of the Searlean analysis of meaning intentions,33 (H1.1) has to be annotated as follows. First, Y must be characterized by certain conditions of satisfaction; second, P must believe that K has the same conditions of satisfaction as Y. These conditions must be fulfilled if we are to be able to maintain the core idea of the Searlean theory of meaning—namely, that mind, in completing an act of expression, “intentionally imposes the same conditions of satisfaction on the physical expression [K] of the expressed mental state, as the mental state [Y] has itself.”34 However, as clear as this analysis appears to be at the outset, on closer examination it is quite confusing. It is clear that artistic actions seldom have the character of expressive, directive, commissive, or declarative acts. In any case, such acts are not typical of artistic action. (H1.1) must thus be interpreted in terms of expressive acts. Here it is initially questionable how P can come to believe that K is a means to express Y. In contrast to the four mentioned types of speech acts, this belief cannot take recourse in intentionality having a word-to-world or a world-to-word direction of fit, and thus in conditions of satisfaction that are intersubjectively observable. An expression differs from an utterance about an observable state of affairs, whose meaning intention can be related to observable conditions of satisfaction, that is, to the claim that it is true, which is satisfied if the belief that is expressed is fulfilled. For an expression, however, this possibility does not exist. In expressive acts, the belief that K is a means to express Y refers solely to the intention that K ought to be a means to express Y. Only the intention to express Y is necessary to determine what is considered an expression of Y. It follows that in the expressive speech act “to believe that K is a means to express Y” is the same as “to intend that K is a means to express Y.”35 However, if intending that K is an expression of the Y-state is sufficient for K to be an expression of the Y-state, then the conditions of satisfaction of the expressive intention are self-fulfilling. However, as a consequence of that, such self-fulfilling intentions—which, in interaction with desires, are supposed to ensure that links can be made between the rationalization of action and the standards of rationality of the interpreters—can no longer play an informative or explanative role. For a reconstruction, this structure would revert to an intentional analysis in the following form:

(H1.2)

a. P desires to express Y.

b. P desires that K expresses Y.

c. Therefore, P produces K.

Schema (H1.2), however, now states nothing but that P produced K because P has desires that lead P to produce K. “Explanations” of action of this sort are so free from restrictions that, with their help, any behavior can be interpreted as being steered by desires: the cat is on the mat because it wants to sit on the mat or because it wants its sitting on the mat to express a protest about the absence of the person with whom it shares an apartment. In (H1.2) the constitutive function of the conditions of satisfaction can no longer be regarded as a screen against which the individuating of expressive intentional states occurs because, from the perspective of the interpreter, these conditions can be arbitrarily fulfilled. Because there are no restrictions on what can be inserted into (b), (H1.2) can provide arbitrary explanations, which above all share the following characteristics: they are neither informative nor do they clarify an action with a view to intersubjectively comprehensible standards of rationality. Even if Searle’s analysis of expressive action may be correct, which, in view of the above-noted consequences, is not easy to believe, his analysis does not provide the theoretical means needed in order to understand artistic action. If artistic activities beyond the parameters of (H1.2) are to be explained as actions, it can be assumed either that, with a view to the reception by third parties, beyond the bare meaning intention, the envisioned success of an expression can provide reasons for the choice of a certain means of articulation, or other relations, which limit choices between the content of the meaning intention and the means of the expression, can be found.

In the face of this shattering result, let us initially once again call to mind the problem: (H1.2) places an artistic activity in the context of a meaning intention (Y), which P connects with K, a work of art. Premise (a) indeed fulfills a basic prerequisite for securing artistic action the status of action—the activity is described as intentional. However, it remains questionable how premise (b) is more precisely to be analyzed; this premise is to ensure that an action is able to be related to reasons; further, the explicative character of the rationalization of the action is dependent on it. (H1.1)(b) confronts us with the difficulty of developing a precise view of the belief that artwork is a means for expressing content; for if (H1.1) is supposed to take on the function of rationalizing action, it must be assumed that a robust connection can be made between the products (X) and the assumed goals of the articulation (Y). But what type of relation could that be?

If we assume a strong relation, we must demonstrate the validity of relations between the goals of an expression and the means of the expression, such as the paraphrase or the translation. First of all, however, such strong relations are problematic because it is maintained, for good reasons, that music—as a product of the action of composition—is “essentially untranslatable,”36 and thus it is impossible that there could be a propositional equivalent of what the music intended.37 If the thesis of the untranslatability of music is to be correct, then, on the basis of the symmetry of the translation relation, there cannot be music-extrinsic intentions that might be able to provide details sufficient to explain the structure of musical works. However, if the assumption that music is essentially untranslatable should turn out to be false, then there is a second question about the rationality of the action of the person who is expressing herself, namely, why P does not simply articulate Y (linguistically). The fact that P articulates K in the face of the possibility of linguistic equivalents could only be explained—absent motives such as that one simply has fun articulating K—if Y cannot be articulated by P except with the help of K. However, if that were the case, then in the rationalization of the action, Y could not be individuated independently of K and would have to be replaced by K. Doing this, however, the explanation of the action would become tautological.

If, in the face of the problem with strong relations, one suggests instead that the relationship between the goal of the expression and the means of the expression be determined with the help of soft relations (such as similarity or “kinship”), then, as a result of the ambiguity about what we might put in the place of Y, the explanatory character of such a rationalization of action disappears; for as a consequence of the ascription of soft relations, the definition of the possible goals of the expression would be subject to so few restrictions that a large number of possible applications of (H1.1) would be placed next to one another, lacking any criteria. In contrast to this, the plausibility of the rationalizations of action according to (H1) is not due to soft relations, but to the fact that for X, in (H1), only truth-conditional sentences, i.e., sentences that are open to intersubjective evaluation, can be employed; consequently, the link to the interpreter’s standards of rationality can be secured. However, if we now neither possess strong relations for the connection between K and Y nor are able to secure the link to the interpreter’s rationality standards with the aid of soft relations, then we must no longer rely on (H1.1) as the schema for understanding artistic actions or—and this appears to me to be a much higher price—we must no longer ascribe to artistic activity the status of action. For if characterizing an activity as an action requires that the beliefs that we ascribe to actors in potential rationalizations of action are truth conditional, or at least that they can be tested for appropriateness, then it is not clear how a modification of (H1) can lead to a rationalization of artistic action that can fulfill this condition.

In my view these deliberations bring us to the point that it is necessary to replace the action schema (H1) with a schema that allows artistic actions to be explained in a manner that need not assume (truth-conditional) propositional attitudes. Such a schema thus must systematically anticipate that an artistic intention can only be individuated in the medium in which it is articulated.

In principle, once again it is possible to conceive of two strategies that allow an artistic activity to be described intentionally. While Habermas, with all the well-known problems,38 has gone the route of introducing a truth-analogous validity claim and characterized sincerity as a validity claim that is characteristic for artistic actions, I would like to try to show that artistic action—more fundamentally than in the perspective of a truth derivative—can be understood as a form of action that, by means of a medium, individuates constellations that can be understood as offering a possibility for individuating higher-level intentional states of the recipients. Thus, the view that I would like to bring into play is that by specifying the idea of an intrinsic connection between media and the goals of action that are achieved with its help—which Dewey had quite vaguely formulated39—media can be interpreted as “instruments” for individuating higher-level intentional states; with the help of such instruments, these intentional states can also be articulated. However, that is initially a very abstract and provisional formulation, and it must be further developed. Here it is helpful, first, once again to affirm the presuppositions that are involved in rationalizing action with the help of propositional attitudes. Among these presuppositions are the interpreter’s knowledge of a language and the assumption that those being interpreted possess a language, possibly a different one, but one that can be translated into the language of the interpreter; with the help of this language, those being interpreted might individuate intentional states and order them into a network of beliefs and desires. In connection with Davidson, it must be assumed that principles of basal rationality span and organize this network.

As a consequence of the assumption that the identity of intentional states arises in a network that is fixed with the help of principles of basal rationality and that an elementary logic is a part of these principles, the entities that are organized in this network must be truth-apt; it is precisely this characteristic that cannot be transferred to artistic intention. It is also the lack of this characteristic that hinders the transfer of a theory of meaning based on conditions of satisfaction; for there is no analogue in artistic acts of articulation to the truth aptness of propositional attitudes, along with the individuation of the propositional attitudes, that secures the connection to a logic of duties which those that are being interpreted have to follow, at least in the perspective of the interpreter. Composing a bar of music—even in highly regimented music—does not render the composer a responsibility similar to that rendered to the speaker who expresses an assertion.

In short, the theoretical situation in which we find ourselves after this look at the conceptual tools that the established theory of mind and theory of meaning provide us for reconstructing the understanding of nonlinguistic intentional expressions is as follows:

1. Within the framework of the standard analysis of action, the interpretation of nonlinguistic works of art as products of common action faces the following difficulty: in accord with this interpretation, one has to understand works of art and the intentional states that they express and that are the cause for their production to be linguistically individuated states. Doing this, however, makes analysis irreconcilable with intuitions that we rightfully have about the understanding of works of art, namely:

a. Works of art are intentional products of their producers.

b. Works of art are not completely understood if one identifies the intentions that an artist intended to achieve in producing them.

c. Works of art articulate thoughts that cannot be grasped by a different means than the one in which the work of art articulates the thoughts—works of art are not translatable.

There is thus a need for a theory of intentional states that are not individuated (in a [self-]interpretation) by linguistic means.

2. In connection with Searle (and in connection with the functionalist conceptions of intentionality), a concept of nonlinguistic intentionality can be developed using concepts of a basal intrinsic intentionality. With the help of this concept it is indeed possible to overcome deficits in the developmental history of interpretationist theories of intentionality, but the concept of intrinsic intentionality is not suited to allow an intentional description of artistic actions and to open dimensions needed to understand it.

3. Thus: the type of intentionality that it is necessary to apprehend theoretically is a higher-level form of intentionality, which is at the same time not a linguistically individuated form of intentionality. Thus, in conformity with the intuition that artistic media are means of artistic thought, one should, in accord with those interpretationistic assumptions that remain fundamental for the reconstruction of higher-level forms of intentionality, attempt to develop a theory of nonlinguistic thoughts.

The following section is devoted to the attempt to meet these theoretical demands. In the first step, which is here to be made with a view to a theory of nonlinguistic thoughts, I start from a familiar scenario: two persons with common linguistic competencies discuss a nonlinguistic work of art.

3.2.1.3. After the Concert—An Alternative Analysis

Let us assume the following: after having spent an evening at a concert with someone we hardly know, in the bar after a long period in which the topic strangely did not come up, the topic then turns to the music that we heard just under two hours previously. My question is now the following: Under what conditions would we be ready to say that our companion (P2) has understood the music that we heard together?

Now among the minimal conditions for confidence that P2 has an understanding of this sort is surely that, during our conversation, P2 can refer to the various works that we have heard. For example, if we are speaking about the second piece of the evening, then we must expect that P2 can refer to the characteristics that make the second piece the specific work of art that it is. In short: the person must be able to refer to the work of art as a specific unity or, more precisely, she must be able to refer to the characteristics that are constitutive for the identity of the work of art, because no one can understand something that they cannot identify. This prerequisite need by no means be fulfilled using the language of music studies; perhaps it need not even rely on a language at all. If, for example, with the use of singing, gestures, or sketches, P2 can refer to the characteristics of a piece of music that make that piece of music a piece of music (in the context of the history of music), then the person has fulfilled a central prerequisite for us to be confident that she has understood the piece of music.40 In any case, we will have considerable doubt that P2 understands a work of art if P2’s identifying references to the work of art are so unspecific that P2’s “descriptions” of the characteristics do not identify an individual work of art but a set of such works, and in our case, for example, she interprets the last movement of the first piece and the first one of the second as a two-movement work.

To guard against a misunderstanding: what we expect from a person who fulfills the minimal conditions for understanding a work of art is not only the ability to refer to a work of art as an object, as is possible with the help of proper names or identifying descriptions (“Intégrales” or “that music piece for small orchestra and drums that Edgard Varèse completed in 1924”). Rather, it is a matter of the ability to identify the work of art in relation to its qualities that can be experienced. But even the reference to the characteristics that can be experienced is not sufficient. For it is not about some identification method with the help of which the work of art can, without a doubt, be filtered from the mass of other works of art on the basis of its empirical characteristics—the way the criminal suspect, with the help of a fingerprint, a DNA sample, or a graphological analysis, can be separated from a set of all potential perpetrators. It is rather about identifying the work of art with reference to those characteristics that are relevant for it as this work of art. But which characteristics are those? They are the characteristics that we pay attention to if we, for example, compare the following identifying references to acoustic events:

a. “The piece that I mean is the only one that brings about a feeling in me of cold abandonment.”

b. “The piece that I mean consists of two-dimensional crescendo background noises, which sound like a distant, threatening razor, and of light recurring beats as if one were pounding on tin.”

c. “The piece that I mean begins “Da-da-daa-di da du di da.”

d. The piece that I mean begins

While in (a) reference is made to a subjective association that is not accessible to intersubjective verification and thus hardly offers a suitable indication of the search for the piece, (b) makes reference to the sound structure of the piece, which is described with the aid of comprehensible music-extrinsic sound experiences. Reference (c) presents structural characteristics of the piece that place the listener of the sample in a position to identify the piece whose characteristics are exemplified, as long as the sample does not apply to numerous pieces, and (d) identifies Beethoven’s Piano Sonata, Op. 2, Nr. 1 in the form of the index of a volume of sheet music.

The thought that I would like to bring into play in order to more precisely describe the abilities that a person must have before we have confidence that she understands a work of art consists, in short, in connecting this ability to the fact that, in the act of identification, a set of characteristics must be referred to that were relevant for the production of the work of art and are relevant for most of its characteristics that can be experienced. The work of art should not be identified on the basis of contingent characteristics that are external to it, but on the basis of characteristics that it displays because it was made in a particular manner. If the identification is successful in this way, then a recipient refers to the identity of the work of art, which it has by virtue of the fact that it is a composed unity.41 For its part, this identity, which I would like to call the compositional identity, has its own presuppositions, which I would like to more precisely explain by once more turning to the continued discussion after the concert.