The army that went on campaign in Pennsylvania led by Brigadier-General John Forbes was one of three large Anglo-American armies that advanced on various fronts during 1758. This was the result of a master strategic plan conceived during 1756–57 by John Campbell, Earl of Loudoun, who had been commander-in-chief of the British forces in North America before his recall to England in December 1757. Lord Loudoun, who had served in the entourage of the royal family, had a talent for strategic planning as proven by his plan to invade New France. When he arrived, he inherited the sequels of Major-General Edward Braddock’s July 1755 disaster at Monongahela, the stalemate on the Lake George–Lake Champlain front, and some timid progress on the western frontier of Nova Scotia that was now ravaged by some formerly neutral Acadians that had escaped an unwarranted deportation and exacted their revenge. Indeed, it seemed the frontier was aflame everywhere due to innumerable “French & Indian” raids. Actually mostly Indian raids because many native nations perceived the French as being uninterested in large-scale settlement, while it was obvious to most of them that if the Anglo-Americans came, most Indians would lose everything.

John Campbell, Earl of Loudoun, c.1753. During his tenure as commanderin-chief in North America during 1756 and 1757, General Loudoun formulated the master strategy that was followed by the British government for the conquest of New France. He is shown in the uniform of the 30th Regiment of Foot. (Collection and photo: Fort Ligonier, Pennsylvania)

Finding there was no coherent Anglo-American war plan, Lord Loudoun conceived an invasion strategy for the conquest of Canada that would be followed by his successors and the British government for the rest of the war. This strategy called for overwhelming forces to be deployed on three fronts: the Ohio Valley, the Lake George–Lake Champlain–Richelieu River area towards Montreal, and the Fortress of Louisbourg on Isle Royale (Cape Breton Island), which would lead to the St. Lawrence River and Quebec. The final objective was Montreal, where all three armies were to meet. Loudoun had correctly perceived that it was Montreal, and not Quebec, that was the real strategic and commercial key to New France. This grand strategy called for the capture, amongst other objectives, of Fort Duquesne to secure the Ohio Valley, and thus allow the British and American forces to move up to Lake Erie and, eventually, Lake Ontario.

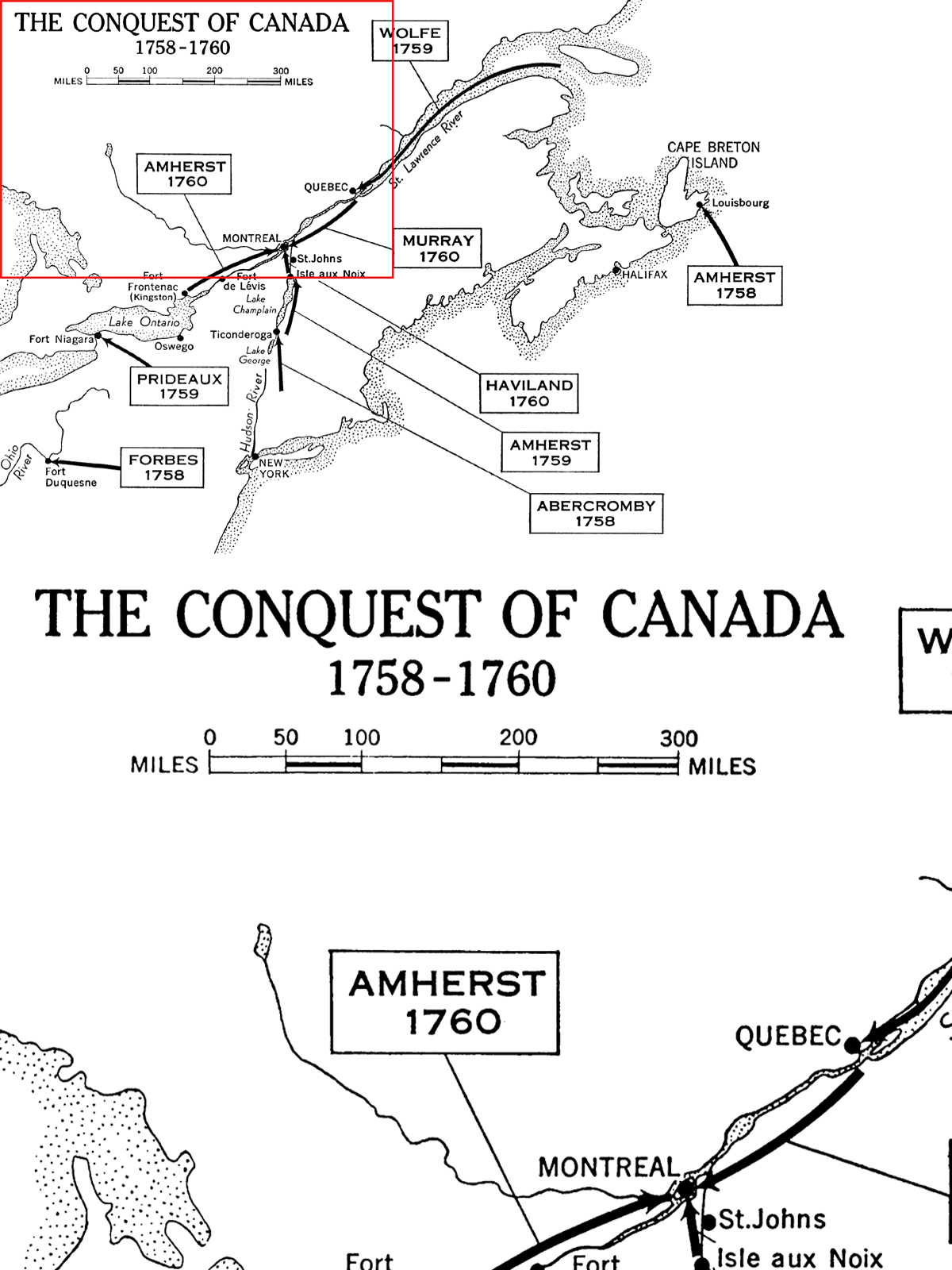

Strategic map of the conquest of Canada, 1758–60; Lord Loudoun’s grand strategic plan was carried out over three years. In 1758 two of the year’s three objectives fell: Fortress Louisbourg in July and Fort Duquesne in November. They were repulsed at Fort Carillon (Ticonderoga), but took it the following year along with Quebec and Niagara. In 1760 three armies marched on the ultimate objective, Montreal, where the French army capitulated on September 8. (Collection and photo: Directorate of History and Heritage, Department of National Defence, Ottawa)

The missing element of the British and American war plans was the question of the Indian nations. General Braddock’s 1755 defeat on the Monongahela had made it abundantly clear that there could be no sustainable penetration in the hinterland without a dramatic shift in policy regarding Indians. For generations the French had lavished considerable effort and money to sustain a diplomatic stance towards the Indian nations that brought them either their alliance or at least their neutrality. The result was that, apart from a few recalcitrant nations, the French held sway through their allies in North America’s hinterland to the very edges of the forests that bordered the British colonies. There was one large exception to this situation on the outskirts of the colony of New York: the League of the Six Nations making up the Iroquois Confederacy. These were the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, Seneca, and Tuscarora nations. The sixth and most recent nation was the Tuscarora, which had been at war with and defeated by North Carolina settlers in the early 18th century, moved north, and been adopted into the league. The original five nations had come together to create the confederacy in about 1570 and had spent much of the next century launching devastating hostilities on French-allied nations, such as the Hurons, as well as on the French settlements and outposts. Somewhat let down by the English when the French mastered the art of wilderness warfare in the 1690s, they adopted a more neutral position. However, most Iroquois, especially the original five nations, remained attached to Great Britain. Those among them that had more sympathies for the French had moved to live in the area around Montreal. Thus, the majority who remained in what is now upstate New York favored allegiance to the British “King George” and hoped for more attention from his officials. This came in 1755 with the appointment to the new post of Superintendent of Indian Affairs of a most talented Englishmen that lived in their midst: William Johnson. He was gifted with outstanding diplomatic ability as well as a good understanding of military command, which he had promptly displayed by rallying the Iroquois and, in September 1755, defeating a French metropolitan regular force that attacked an American provincial army at Lake George, even capturing its wounded French general, Baron Dieskau. For these amazing feats, he was knighted.

Sir William went on to many more successes during the war in the northern areas. But the superintendent had little influence, if any, on Indian nations in the Ohio Valley and its surrounding areas. This was the domain of the western Delaware (called the Loups – Wolves – by the French), Shawnee, and Mingo nations. In turn, they had welcomed and often fought alongside many warriors that had come from further west and the Great Lakes belonging to the Ottawa, Wyandot, and other nations allied to the French that had set up their camps near Fort Duquesne.

If the British and Americans were to have a chance to succeed in regaining the Ohio, their Indian diplomacy would need a great deal more attention, something that Sir William Johnson could not effectively give, not only because he was much too preoccupied in the north, but also due to his connection with the Iroquois, which did not necessarily endear him to most Ohio and Great Lakes nations. During 1756 and 1757, Indian diplomacy in the Ohio, while all-important to the French, was not a great priority to the British and Americans, who were then preoccupied on other fronts and busy mustering as many troops and warlike stores as possible to implement the great strategic plan devised by Lord Loudoun. Following this plan, an Anglo-American army would march into the Ohio to secure Fort Duquesne. No one wanted a repetition of the disaster on the Monongahela, and for that not to happen, quite apart from a new tactical approach, there also needed to be concerted and massive efforts to neutralize the Ohio Indian nations at the very least.

In London, Prime Minister William Pitt defined the command structure of the Anglo-American forces and their objectives for the following year in a letter dated December 30, 1757 and received at New York on March 4, 1758. In terms of command, Sir James Abercromby replaced Lord Loudoun as commander-in-chief in North America. In 1758, imperial strategy would be exerted on three fronts. The most important in terms of military and naval resources would be an attack on the Fortress of Louisbourg by a large British fleet of more than 150 ships manned by 14,000 sailors and marines under the command of Admiral Boscawen, and transporting some 13,000 British regular soldiers led by Major-General Jeffery Amherst.

Territorial map of the Indian nations in the Great Lakes and Ohio Valley regions in the 1740s and early 1750s. Except for the almost annihilated “Renards” (Fox) nation at left, the various nations were either French allies or neutral. The data was compiled for years before the map was actually drawn up in Paris by cartographer Bellin and “communicated to the public” in 1755. (Library and Archives Canada, NMC 192944)

Meanwhile, Sir James Abercromby would advance up Lake George and take Fort Carillon at Ticonderoga and Fort Saint-Frédéric (Crown Point, New York) on the southern shore of Lake Champlain, leading an army of some 17,600 men of which nearly 6,000 were British regulars.

The third front consisted of an advance across Pennsylvania to expel the French from the Ohio. The force gathered to achieve this goal was to be smaller – about 6,500 men, of whom nearly 5,000 were American provincial troops, and the remainder British regulars.

In terms of the strength of the French forces they were to face, all three Anglo-American armies had greatly superior numbers of troops compared to those of their respective opponents. There was, however, a sizable difference between the projected Ohio Valley campaign and the two others. In the case of moving upon Ticonderoga and Louisbourg, it was expected that the French would have several thousand regulars as defenders, and that, especially for Louisbourg, trains of siege artillery would be required and probably a European-style assault by lines of British troops on fortified positions. In the Ohio, the operation consisted really of a very long-distance raid by a very strong force on a very weak but strategically all-important position made almost impregnable by its very remoteness in the wilderness.

Lieutenant-General Sir James Abercromby, c.1755. He was commander-in-chief in North America during 1758. (Collection and photo: Fort Ligonier Museum, Ligonier, Pennsylvania)

To command the smaller army that would strike towards the Ohio, Prime Minister Pitt selected Colonel John Forbes, commander of the 17th Regiment of Foot already in Halifax, Nova Scotia. The 17th stayed in Halifax as part of the army intended to attack Louisbourg, but its colonel was promoted to brigadier-general and instructed on March 14 by General Abercromby to go to Philadelphia and organize his new army. Forbes had been born in Edinburgh, Scotland on September 5, 1707 and entered the army aged 22 as a surgeon in the 2nd Royal North British Dragoons, also known as the Scots Greys, later becoming a subaltern officer. By 1744 he was a captain and had been at the battle of Dettingen, Germany the previous year. He would again see action at Fontenoy in 1745 and Lawfeld in 1747. Obviously a bright and hard-working officer, he was noticed by senior commanders and became an aide-de-camp to Sir John Campbell. Then, in December 1745, he was promoted deputy quartermaster-general of the British cavalry in the Duke of Cumberland’s army in Germany with the rank of lieutenant-colonel. In that function he gained valuable administrative experience that would later serve him well in Pennsylvania. After the end of the Austrian Succession War in 1748, he went back to Scotland and became lieutenant-colonel of his old regiment, the Scots Greys, and colonel of the 17th Regiment of Foot in February 1757. At that time Forbes was still a bachelor, but he was starting to experience some problems with his health. Nevertheless, his administrative experience was sought in North America and he soon joined Lord Loudoun in New York as adjutant-general.

Brigadier-General John Forbes, c.1750. He is shown wearing the uniform of 2nd (Scots Greys) North British Dragoons. (Collection and photo: Fort Ligonier, Pennsylvania)

Forbes was now one of the key officers on the staff of the commanderin-chief for North America, where he was perceived as competent enough to be recommended to the prime minister for higher command. Pitt, no doubt feeling there would be a great deal of administrative work in preparing the army to move on to the Ohio, wisely selected Forbes, who had management skills as well as experience in battle. One aspect unknown to everyone, however, was Forbes’ health – as months passed, he seemed to suffer more and more frequently from a digestive ailment.

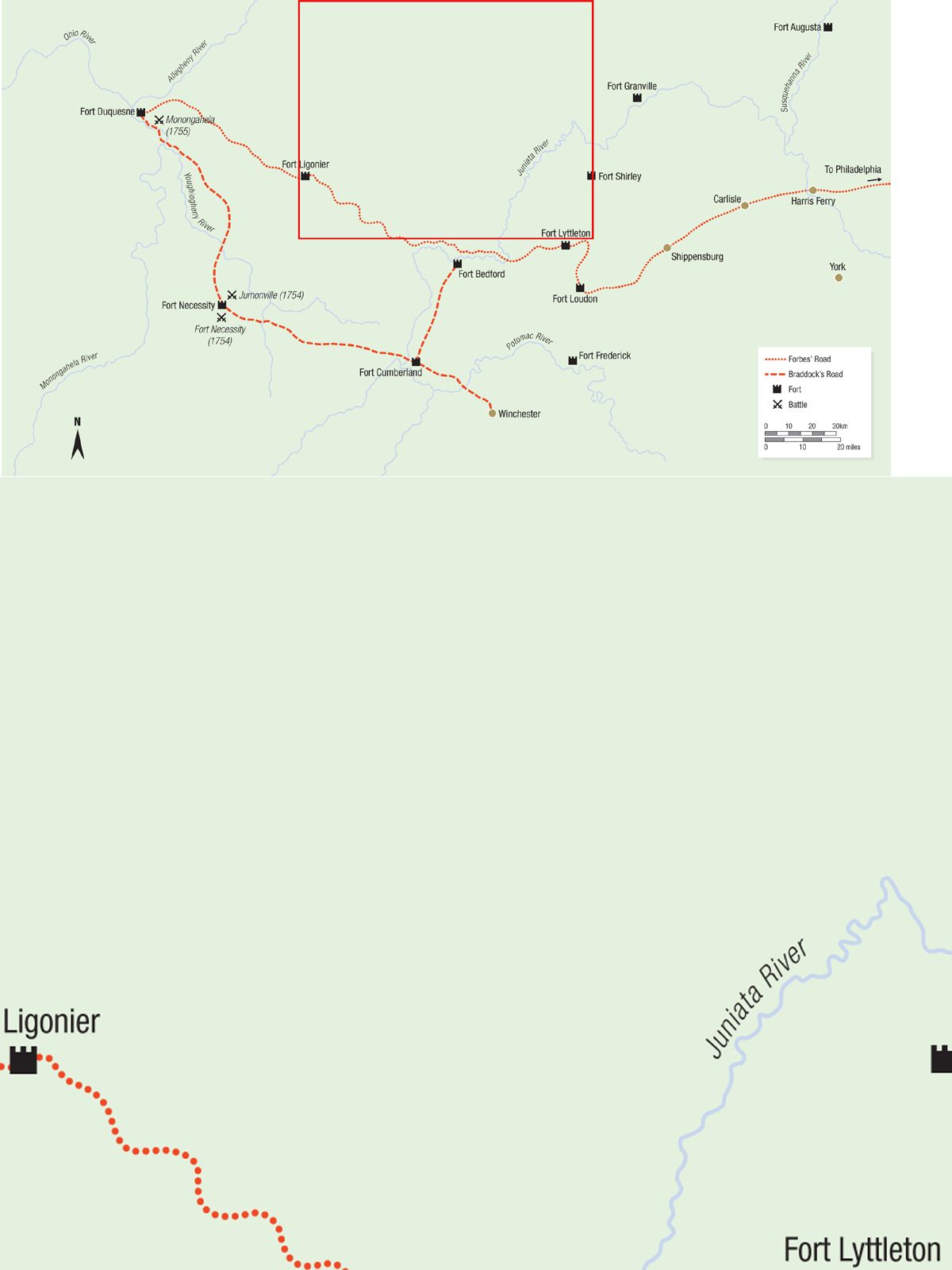

The routes of Braddock’s and Forbes’ Roads.