Meanwhile, Forbes’ army was slowly progressing from Fort Bedford to the next area selected as a major base, a place called Loyalhanna (also called Loyal Hannon or still Royalhanna and spelled several ways). In early August Colonel Bouquet was moving ahead through some very difficult terrain with the spearhead of the army numbering at least 1,500 men with hundreds more required to assist on the road construction. By September 7, he reached Loyalhanna and started setting up a fortified camp. Being in that area was not necessarily a safe proposition. Within a few days of the arrival of Bouquet with the army’s vanguard, small parties of enemy Indians were lurking about with, possibly, some Canadians with them also. Several isolated men were attacked and several killed. An alarmed Bouquet wrote to Forbes that he was “surrounded by Indian [war] parties” and detached about 200 men to guard the access to his camp (Bouquet, II: p. 513). Amazingly, for the French and Indians there, this contact with an Anglo-American detachment does not seem to have registered as being the forward party of Forbes’ army. It would appear that, to them, Bouquet’s force was just another patrol and the real advance was expected to come from Braddock’s Road.

Fort Duquesne – the objective of General Forbes’ army in 1758. Model at the Fort Pitt Museum, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. (Author’s photo)

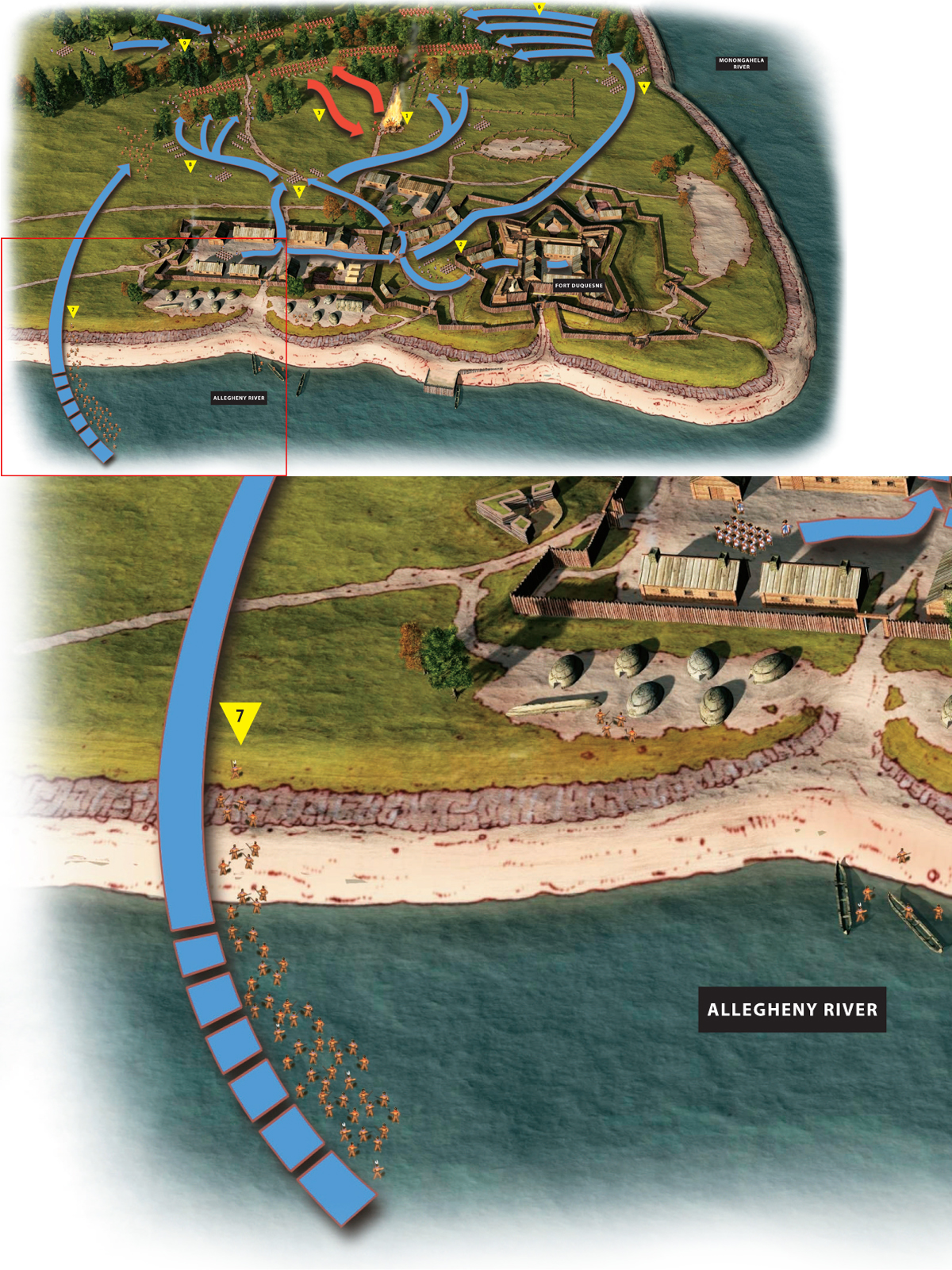

Major Grant’s raid on Fort Duquesne

Having been alerted to the presence of Grant’s troops, the garrison at Fort Duquesne formed a strong column under Captain Aubry while Commandant Lignery held a perimeter near the fort. Aubry’s column of French soldiers and Canadian militiamen edged the Monongahela River, seemingly unseen by the Anglo-Americans, then turned into the wood covered hills and fell upon the flank of Grant’s force. In raid warfare, the best option when attacked is to raid the raiders and that is what these seasoned French and Canadian wilderness fighters did. Firing from behind cover – and the Canadians were renowned marksmen – and rushing in with tomahawks and knives to the sound of fearsome war whoops, the French and Canadians devastated the regular troops who were trained for linear tactics with muskets and bayonets. Their unfamiliarity of the Anglo-American force with this frontier style of warfare is revealed in the huge number of casualties they suffered compared to the few on the French and Canadian side.

Major Grant of the 77th Highlanders pressed Colonel Bouquet to let him lead a strong party to Fort Duquesne. The idea had earlier been rejected by General Forbes, but Grant did not give up. His concept was to punish the enemy Indians that camped outside the fort where they felt perfectly safe. These were the same Indians that, with encouragement from their French and Canadian allies, plotted raids on the American settlers, villages, and even on isolated parties of regular or provincial troops. This was presently the case with Bouquet’s force at Loyalhanna. Such a raid would secure the advance guard better, and correct intelligence about the fort and its garrison would also be gathered. A night attack, something relatively rare at that time, was mooted. Against his better judgment, Bouquet finally agreed. Troops and supplies were trickling in from Fort Bedford every day, so he had enough men to make up a sizable raiding party. In a few days General Forbes would travel from Fort Bedford to the new fort, called Ligonier, that was being built at Loyalhanna. Unfortunately, the general’s condition seemed to be worsening and he had to be carried in a litter set up between two horses, but he was still quite sound enough to exercise his command fully. He did not know about Grant’s initiative and Bouquet’s approval.

The Pennsylvania Gazette ran the following account of Grant’s expedition: “On Monday 11th of September, Major Grant of the [77th] Highland Regiment, marched from our camp…with 37 officers and 805 privates…” It was actually even stronger, having 860 other ranks. On the 13th they were

within two miles [3.2 km] of Fort Duquesne and left their baggage there, guarded by a captain, a subaltern and fifty men, and marched with the rest of the troops, and arrived at eleven o’clock at night upon a hill, a quarter of a mile from the fort. Major Grant sent two officers and fifty men to the [outskirts of the] fort to attack all the Indians, &c., they should find lying out of the fort; they saw none, nor were they challenged by sentries. As they returned, they set fire to a large storehouse, which was put out as soon as they left it. At day break, Major [Andrew] Lewis was sent with 400 men (Royal Americans and Virginians), to lie in ambush a mile and a half from the main body, on the path on which they left their baggage, imagining the French would send to attack the baggage guard and seize it. Four hundred men were posted along the hill facing the fort, to cover the retreat of Captain McDonald’s company, who marched with drums beating towards the fort, in order to draw a party out of the fort, as Major Grant had some reason to believe that there were not above 200 men in the fort, including Indians; but as soon as they heard the drums they sallied out in great numbers, both French and Indians, and fell upon Captain McDonald, and two columns that were posted lower on the hill to receive them. The Highlanders exposed themselves without any cover, and were shot down in great numbers, and soon forced to retreat. The Carolinians, Marylanders, and Lower [Counties] Countrymen, concealing themselves behind trees and the brush, made a good defense; but were overpowered by numbers, and not being supported.

Major Grant was exposed in the midst of the fighting and tried “to rally his men” but to no purpose, as they were by this time flanked on all sides. Major Lewis and his men came up “and engaged [the French and Indians], but were soon obliged to give way, the enemy having the [height] of the hill of him, and flanking him every way.” Some were driven “onto the Ohio [River], most of whom were drowned. Major Grant retreated to the baggage, where Captain Bullet was posted with fifty men, and again endeavored to rally the flying soldiers…but all in vain, as the enemy were close at their heels.” Attempting to contain the French and Indians, Captain Bullet “attacked very furiously for some time, but not being supported [by other troops], and most of his men killed, he was forced to give way.” Major Grant and others were captured, but Captain Bullet made his escape and related that he had last seen Major Grant surrounded on all sides, “but the enemy would not kill him, and often called to him to surrender. The French gave quarter to all that would accept it” (DCHNY, X: pp. 902–903).

This confused attack, seemingly not sticking to a particular plan, was preceded by a night of confusion during which the troops were told to put their shirts over their other clothes to be able to identify friend from foe in the darkness. This was a standard procedure on such occasions. But, for a variety of reasons, there was no attack and certainly no surprise. Miscalculation of the distance, a thick fog, and some parties of the attacking force getting lost in the dark were among the obstacles that prevented the night attack, and the soldiers were now in “the greatest confusion” among Major Lewis’ 400 men. The shirts must have come off at dawn. In spite of all that, the raiding force had been incredibly lucky because it still had not been detected by the French and Indians. Instead of calling off the attack, as Bouquet had instructed, Grant now announced to the enemy he was there. Throwing away the advantage of a surprise attack, the Anglo-Americans advanced to the sound of the drums that, in this Pennsylvania wilderness context, must have been as strange as having Indian war whoops at the battle of Rossbach in Europe. The following French accounts relate the ensuing disaster.

On November 1, 1758, the report of Grant’s raid by Governor-General Vaudreuil went from Quebec to his superior, the minister of the navy, in Versailles. It collated various reports coming in from the Ohio, some of them undoubtedly verbal. According to this dispatch

on 11 September [1758] Major Legrand [Grant], commanding the Scottish Highlanders that are part of the enemy’s army, with 960 men of elite troops…arrived on the 14th in the area of Fort Duquesne. He left 450 men… [in the rear as skirmishers]… and as he planned with the rest of his troops to attack Mr. de Lignery’s camp at [Fort Duquesne during the] night by moonlight, he had his soldiers put on white shirts over their clothes for recognition…the watchful guards of Mr. de Lignery having prevented [Grant’s troops] from proceeding with his plan, he [Grant] withdrew once he reached the outskirts of the fort…. Major Legrand [Grant], seeing his attack compromised, had the drums beaten to lure the French [garrison] out and charge them, believing them to be a small number. The sound of the drum made the soldiers and the Canadians come out of their tents and huts…all wearing shirts, officers as well as the others, making Indian shouts… The fight was brisk and stubborn…the loss of the English was 400 killed, a large number wounded and at least 100 made prisoners including the commander [Grant] and other officers. We lost 8 Canadians killed and 8 wounded… Mr. Aubry, captain of the troops of New Orleans as well as all officers of the detachment from the Illinois gave proof of great valor in this affair…1

SEPTEMBER 14, 1758

Undetected during its approach, the Anglo-American force announced its presence by setting fire to an outlying building and signaling the advance with pipes and drums. In the fort, the alarm was raised and, within minutes, the defenders assembled. A force under Captain Aubry headed along the bank of the Monongahela, towards the hills occupied by Grant’s force, while Commandant Lignery remained with some 200 men at the fort. Once he reached the hills, Aubry’s force turned into the woods and fell upon Grant’s flank. Meanwhile, Indian allies, most of whom appear to have been camped across the Allegheny, had been also alerted and entered the fight in increasing numbers. The Anglo-American advance slowed then stopped as it was overwhelmed by expert woodsmen in an environment for which it was unprepared. Soon, panic set in and the Anglo-American force broke, with many who could not swim attempting to cross the Monongahela and Grant himself being captured. The raid was an absolute and costly fiasco.

EVENTS

EVENTS1 A small Anglo-American forward party sets an outlying shed on fire.

2 The French sound the general alarm and assemble within minutes.

3 Major Grant orders an advance with drums beating and pipes playing.

4 A column of about 500 men under Captain Aubry heads toward the hills, edging the Monongahela River.

5 Approximately 200 men under Commandant Lignery fan out in front of the fort.

6 Aubry’s column turns into the wooded hills and falls upon the flank of Grant’s force.

7 Indians, most of whom are on the far bank of the Allegheny, cross the river and advance towards the hills.

8 Lignery’s men join in the battle.

9 Grant is captured.

General Montcalm, commander-in-chief of the French forces in Canada, was more concerned with matters closer to the St. Lawrence Valley and the Lake Champlain area, but also was kept informed of events further away. In October his journal included extracts from a September 16 letter from Mr. Du Verny, an “artillery officer detached at Fort Duquesne” regarding Grant’s raid. On September 9, Du Verny wrote, intelligence was received that Forbes’ army was about “twenty leagues” away and building fortifications there so that scouts were immediately sent out. They came back with the news that the “English army was on the march” but more scouts found that the area seemed to be quiet. They had been looking at the wrong area because on the night of September 13/14 some caught an Englishman who had got lost in the woods looking for strayed horses. Brought back and questioned in Fort Duquesne, he could tell little else to his captors. Nevertheless, here was proof that some enemy force was approaching. At early dawn on the morning of September 14, Du Verny went on

we saw fire in a shed [well outside the fort] and we perceived it had been set by the enemy. A report was made [by the sentries]. A party of 200 men was immediately ordered to make a reconnaissance in the [nearby] woods. As they marched out, at seven in the morning, approaching the woods, they heard many drums and fifes beating, which was also heard in the camp and in the fort. Within six minutes, the French were assembled and headed for the area led by Mr. De Lignery. The action soon began and did not change places. The shooting was very brisk during half an hour; it took much effort to convince the Indians, who were busy ferrying their booty from one shore [of the Ohio River] to another, and I thought I could do nothing better than take their lead and encourage them to join the French who had already gained the advantage [in the battle]. The rout of the enemy was soon complete. We pursued them for three hours. The greater part of this enemy detachment, of about 800 men, was badly mauled or taken prisoner. A small portion swam across the Monongahela River under fire from us and the rest fled in all directions… From that moment, new prisoners were brought every hour of which the greater part fell to the cruelty of the Indians. The commander of this detachment was captured during the fight with several other officers, and many were killed including their engineers. According to the statements of the prisoners, this was merely a detachment of 800 men which had come to reconnoiter and mark [the way to build] a road for an army of seven to eight thousand men that is assembling to come here [at Fort Duquesne] with 18 pieces of artillery.

He added that “we lost ten men, a few wounded; I estimate the loss of the enemy at three or four hundred men.” But, Du Verny went on, in spite of this success, “the Indians left us after having made their blow and we were not able to stop them.”

Montcalm’s aide-de-camp, Louis-Antoine de Bougainville, also mentioned that “a detachment of 800 English, partly regulars, partly militia, had marched very secretly from Pennsylvania…by a very different road from General Braddock’s” and “posted themselves at daybreak on a mountain near Fort Duquesne, and made arrangements to facilitate its reconnaissance by an Engineer whom they had brought along. But the troops of the Marine and the Canadians, to the number of 700–800 men, did not give them time. They pounced suddenly from all sides on the English, and immediately threw them into disorder. Our Indians who at first had crossed the river, fearing to be surprised, also charged right vigorously. It was nothing but a route on the part of the enemy. 500 of them have been killed, taken or wounded, and almost all the officers [were also killed or taken]. On our side, only eight men have been killed or wounded” (DCHNY, X: p. 888).

J.C.B. left a short but revealing account of Grant’s raid in spite of having been written about four decades after the event. Of those on the French side who left writings of the event, he was, with De Verny, the closest to the action, being in Fort Duquesne as its storekeeper when it occurred. According to his memoir

An army commanded by General Gicent [Major Grant]…had the intention of taking Fort Duquesne by surprise. He consequently had his drums beaten on the shores of the Ohio to lure the [fort’s] garrison there, while he was on the shore of the Monongahela River with most of his army to rush on the fort as soon as he would have seen its garrison go away from it. But his plan was foiled. Captain Aubry came out of the fort with about 500 men and, instead of going to where the drums were beating, advanced along the shore of the Monongahela and soon came upon the enemy. The fighting started immediately and was very sharp so that the enemy was put to flight after losing 300 men. Thirty-five prisoners were made including seven by the Indians who gave them to the commandant. The French only had one killed and five wounded, these light losses being because they fought behind trees while the enemy was in the open field.

The commandant of Fort Niagara, Captain Pierre Pouchot, later recalled that on

14 September, 800 Scots and [American] militiamen, under the command of two majors, approached at daybreak right up as far as the cleared ground created around Fort Duquesne, without being spotted. The [American] militia major [Lewis] was hesitant to attack, but the Scotsman, Major Grant, reluctant to turn back without doing anything, had a small shed in an outlying area of the fort set on fire to provoke an engagement. The Canadians [militiamen] and a few Indians, who were lodged in huts around the fort, noted this unusual early morning fire and were curious enough to slide down into the brushwood in order to discover what was happening. They went one after the other. Since the Indians and Canadians wear nothing more than a shirt in fine weather, they were very soon ready for action. Those who arrived first saw the [Anglo American] troops and began to fire on them. The English beat the retreat, causing the alert to be sounded in the fort from which assistance was sent to the first men who had sallied forth from it. The enemy corps was so vigorously attacked that 250 scalps resulted and 100 prisoners were taken, among them six officers and the two majors. The remainder were pursued into the forest, where most of them perished.

Regimental color of the 77th (Montgomery’s Highland) Regiment, c.1757–60. (Reconstitution. Collection and photo: Fort Ligonier Museum, Ligonier, Pennsylvania)

For his part, General Lévis, second-in-command in Canada, consigned the following account of Grant’s defeat

Before leaving Carillon [Ticonderoga], we learned during the last days of October from [Governor] General Vaudreuil that an enemy detachment of 900 men commanded by Mr. Grant, major of one of the Scots battalions, and a major of [American] militia, had advanced up to canon range of Fort Duquesne to attack by surprise during the night the camp of the Canadians and the Indians we had at that place. The enemy detachment was at dawn sighted by our Indians who shouted and gave the alarm to the Canadians. Mr. De Lignery who was in command at that place ordered everyone under arms, which consisted of about 1,500 men, who marched at once towards the enemy [troops] who were very surprised to [see] such a large number. They thought we had no Indians and we had five to six hundred surrounding the enemy detachment, which was defeated in a short time. They had 500 men killed or captured; no more than 300 escaped the same fate by fleeing. Mr. Grant and the militia major were made prisoners with three [other] officers. We lost only 20 men killed or wounded.” However, he went on to state that the prisoners said that General Forbes was advancing “with an army of 6,000 men to attack Fort Duquesne; that the detachment led by Mr. Grant was merely an advance guard sent to reconnoiter the road; that the army of General Forbes had taken a different road than that of [General] Braddock…and was entrenched at Royal-Hanon, about 18 leagues from Fort Duquesne.

These accounts, some of which appear to have been related verbally by men coming from the Ohio to officers in Canada, have many discrepancies on casualties and on who actually led the French force that attacked Grant’s troops. With regard to leadership, Lignery was certainly the one who ordered the garrison mustered and led it out of the fort. One notes that this was done quite fast, within six minutes according to Du Verny, which indicates that all followed a plan that had been previously worked out to cope with such an alarm. Lignery most likely did not personally take part in the French attack, probably because he was more elderly and would remain in charge of the men left in the fort and its immediate area, notably the 200 men mentioned by Du Verny. Captain Aubry was the obvious choice to lead the column’s charge as reported by J.C.B. and alluded to by Governor-General Vaudreuil. All the accounts are quite vague as to where the fighting occurred, other than being in the large area of the wooded hills east of the fort. J.C.B. is the only one that mentions the direction taken by the column led by Aubry and it makes perfect sense. In a true counter-guerrilla tactic, he outflanked and surprised his enemy. The rest of the French soldiers and Canadian militiamen at and near the fort were keeping the Anglo-Americans occupied along the edge of the woods while Aubry made his flank movement; they then also charged in when the Anglo-Americans were being attacked on their flank and rear. Indians were not initially involved in great numbers, but that must have changed as more and more crossed the river to join in the fight, their war cries and fearsome appearance surely adding to the terror that eventually overtook Grant’s men. Grant tried to make a last stand and rally his men, but to no avail. The panic must have been considerable when one considers that many men – in an age when few knew how to swim – drowned trying to cross the river.

The French and Canadian casualties were obviously light, but certainly not as few as in J.C.B.’s account. Between 15 and 20 dead and wounded is probably in the right range. The Indian casualties are not reported, but they must have been light also. The Anglo-American casualties were very high. Out of 38 officers, 14 were killed, including Chief Engineer Rhor, 16 were wounded and escaped, and eight were taken prisoner, including majors Grant and Lewis. Of the 860 NCOs and enlisted men, there were some 335 killed, of which 187 were of the 77th Highlanders, 35 of the 60th, 62 of the 1st Virginia Regiment, 27 of the Maryland Provincials, 18 of the 2nd Pennsylvania, four from North Carolina Provincials, and two from the Lower Counties. Some 40 wounded other ranks managed to escape to safety with another 485 that were not wounded. The raiding force had suffered a forty percent loss, a bad “butcher’s bill”.

“My heart is broke,” wrote General Forbes when he heard of this extraordinary French and Indian success over the Anglo-American army. But nothing further was done, and it seems everyone on the Anglo-American side tried to forget about this grand fiasco and probably suppress or make light of it. Eventually, Grant was released on October 14, 1758, and yet was never court-martialed for his truly bumbling and utterly confused leadership. It seems a pity because valuable tactical lessons would have been learned. However, General Forbes was a fellow Scot and historian Douglas R. Cubbison suspects a Scottish cover-up, a theory that the author of this book certainly entertains.