2

The First Root

The Reality and Goodness of the World

[Jesus said,] The Kingdom of the Father is spread out upon the earth, and [people] do not see it.

THE GOSPEL OF THOMAS (LOGION 113)

If you do not see God in everything, you will not see God in anything.

YOGI BHAJAN, 20TH-CENTURY TANTRIC MASTER

As human persons, we negotiate reality through multiple fields of experience. We engage the three-dimensional, physical world through our senses, and we engage the inner realms of imagination, emotion, and logic through other organs of active perception. We can experience time as linear or as cyclical, and we sometimes have intimations of timelessness as well. We can perceive the activity and monologues of our own minds and from time to time can drop into a fertile stillness that words cannot describe. We can experience a sense of isolation, and we can experience a sense of connectedness and oneness with all of creation. We can reflect upon our lives and find a single, sacred narrative thread, and we can reflect again another day and find scattered, isolated events that seem empty and confusing.

As we gather and reflect upon these various fields of perception and experience in our lives—the mundane and the sublime, the joyful and the heart-wrenching—we begin to wonder what in all of this is real, and what if anything is within our power to change. Is the elimination of suffering possible, and if so, how? Are the moments of ecstasy and joy in our lives what are truly real, or is tragedy the true nature of existence? How much of our own peace and happiness is up to us? Is the world “out there” something to flee or something to embrace? Is our inner world more real, or the outer? Do they both exist, and if so, are they even different worlds? Often such questions are precipitated by pivotal events in our lives: births, deaths, and other major life changes.

I have seen in my own life that the answers we hold to such seemingly theoretical questions actually bear very practical results.

Shortly after my twentieth birthday, my mother died after a three-year battle with cancer. As her only surviving child, I had always been extremely close to her, and we enjoyed a deep, healthy, and life-giving relationship until her death. While I had done plenty of grieving during her illness, when she died I did not allow myself to mourn. According to my beliefs at the time, what was most real about the human being was something that could and did exist apart from the body: an eternal soul or divine spark or atman. Death was largely inconsequential, or at least ultimately an illusion. Death was merely a shift, a liberation, in fact, of the core of individual reality from the darkening and limiting husk of the physical body to something far finer.

Armed with this philosophy, I was determined to prove my spiritual maturity through responding to my mother’s death with stoic aplomb. I did not cry at her funeral; in fact, I served as the pianist for her funeral Mass and kept my composure throughout the day, being the gracious host to the many who had come to honor her memory. I worked hard to replace the difficult images of her last days and hours with pictures of her transfigured and at peace, making this substitution in my mind less than an hour after her death. I refused to engage her dead body, telling myself and others that the body was of no consequence: it was no longer her. This way of negotiating my mother’s death proved to be an excellent short-term insulator against difficult and painful emotions. As a further benefit, I was able to soothe my lonely and sad self with reflections on how spiritually advanced I must be; after all, I had not even cried at her funeral.

Shortly after her death I experienced a year-long series of dreams. In these dreams I would see my mother here and there slipping through a large crowd but could never seem to connect with her or get her attention. In some dreams I would see her walking past me but became frustrated because I had lost the ability to speak or move and couldn’t call to her. Sometimes in these dreams I would call her on the phone and there would be no answer, or I would get an old-fashioned busy signal over and over again. These dreams caused me great agitation, and upon waking I would find myself breathing hard and soaked with sweat. I would try to push down the deep sadness that would visit me after these dreams with affirmations of my spiritual philosophy: death was an illusion, all that finally mattered was the eternal soul, and I had no reason to be sad.

Finally, over a year after her death, I had a dream that closed this series. In this dream I was in my parents’ house and something funny had happened. I picked up the phone to call my mother and tell her about this funny event. As the phone rang multiple times, I thought within the dream, “Oh, that’s right. They don’t have any phones there,” and hung up the phone. As the phone receiver clicked onto its carriage, I woke up with a sense of calm. This time I let the sadness remain with me. I had, in my dream life at least, finally admitted that she was gone, that her death was real.

My father died fifteen years later. On the last night of his life, my wife and I returned to the nursing home late in the evening, after having gone out for dinner with family, to say goodnight to the dying man, silent and still for two days already. We arrived only moments after he died, as his body was still quite warm. We did not immediately call the nurse. Instead, we spent time alone with him in the quiet room, now only dimly lit, as night had fallen. I took a few unhurried moments to stroke his hair, touch his cheek, and offer his body the veneration of my touch and tears.

By this time in my life I was no longer an intellectual but nervous twenty-year-old. Older now, I had grown tired of using the life of the mind to absent myself from a reality that kept me scared and inwardly running. I wanted to fully inhabit my life, the laughter and the ecstasy of it as well as the equally holy times of sorrow and anxiety and frustration. Having put aside spiritualist metanarratives and exotic cosmologies, I was now more interested in tasting the vitality of the actual life I was living—an embodied life full of laughter and pain and particularity and sacredness and uncertainty—rather than keeping myself safe from finitude and sadness by holding all experiences at arm’s length.

Whether or not my father’s eternal soul or divine spark or atman might now be present to another dimension of reality, my father’s death was real. Engaging his face, trying my best to remember this sacred moment, I did not turn away from his body or from his death. My sense of spiritual reality was no longer a salvific explanation that would save me from an acute emotional difficulty; rather, it was a sense of deep and abiding presence in and through the matter of my life, a sense of the holy soaked into the sorrow, sanctifying it but not removing it. I cried at my father’s funeral and did not play the piano. My only role that day was to be a mourning adult child of a man who had died.

After my father’s death, there was no series of dreams. While my father did from time to time appear in a dream or in deep meditation, these encounters were not marked by anxiety. I welcomed them and found joy in them, even though in life our relationship was often very strained. I believe the wide difference in how I experienced the deaths of my parents was partly due to the wide difference in the ideas I held concerning the meaning and value of the body, the meaning and value of matter and of the world, and the meaning and value of human particularity and its relationship to the sacred. What we think about matter matters. As we look now at different ways to engage questions of the nature of reality that have arisen in the East and West, we will find—perhaps surprisingly—that the answers Christianity offers resonate well with the deeply holistic perspective of Tantra.

THE ADVAITA VEDANTIC SENSE OF THE WORLD

Spiritual teachers, philosophers, and theologians through the millennia have thought deeply about how we experience the world and have wondered about what “reality” itself might really be. The Indian school of Advaita (Nondual) Vedanta teaches that the world of manifestations—the world of time, matter, mentation, and change—is not ultimately real. The orthodox thinkers in this tradition claim that the true nature of reality is unembodied, changeless consciousness; that what is ultimate (Brahman) is pure spirit, veiled to human beings through illusion (maya). This illusion is rooted in a misapprehension of our own nature and the nature of our world as changeable and subject to causation, as truly inhabiting space and time. Advaita Vedanta asserts that matter is unreal because matter is subject to samsara (process or change, such as the growth, development, and decay of our bodies) and causation. Likewise, since our intellectual and emotional lives are both changeable, they too are all part of prakriti, matter, which is ultimately illusory and nonexistent.

The goal in Advaita Vedanta is to realize our atman, that fragment of pure timeless consciousness (chit) resident within us. Advaita Vedanta asserts that this atman is identical to the cosmic Brahman (the Godhead, the Ground of Being), and thus it too is changeless, nonindividual, and unrelated to time-bound, material existence. Realization of the atman brings release from maya, liberation from samsara, and allows us to escape from identification with any aspect of the changeable world, including the body and its sensations, the mind with its intellectual and volitional life, and the heart with its life of emotion and desire.

The philosophy of Advaita Vedanta teaches that this dis-identification is necessary in order to inhabit a state of peacefulness, to know one’s true identity, and to escape the karmic necessity of rebirth and bondage to the material and other causal realms. One of the greatest philosophers of Advaita Vedanta, Adi Shankara (788–820 CE), states this orthodox position clearly and succinctly in his work Vivekachudamani:

Brahman is the only truth,

The world is unreal,

And there is ultimately no difference between Brahman and Atman.

THE TANTRIC SENSE OF THE WORLD

It is understandable that some spiritual teachers would try to negate the reality of the world of change. When we reflect upon our experience, we often find that change makes us uncomfortable and brings up deep feelings of fear. Change often involves periods of pain and the experience of grieving that which is no longer. The relationships that we did not want to end, the mourning of our youth or childhood as we age, the death of loved ones, the loss of jobs or homes, and finally our own death can all create suffering and anxiety. Once we realize that the finitude and samsara that characterize our world will cause us pain, we seek a way out. Negating the reality of the world with its changes and limitations can seem to allow us to escape this whole host of psychic traumas

[b]ecause suffering is thus everywhere at the beginning, the middle and the end, one should abandon samsara, abide in Reality, and thus become happy.1

How appealing a world of changeless pure spirit might seem! However, such a world is also devoid of growth, of welcoming in new life, and of the beauty that comes from seeing Divinity peaking out through the particularities of earthly existence. If we negate the world and dissociate from all process-driven reality, we dishonor the beauty of our own minds and sideline the life of the heart. If we turn away from the world of change, we miss opportunities to offer and receive compassion and love. We miss the excitement of transforming ourselves and our world through enlivening what is most holy in us and in others.

According to Tantra, this most holy part of us is not something that we experience as changeless and lacking in affect but is our very life of desire itself, our erotic life (from eros, loving desire), which drives us to seek union with the Divine and leads us to find love and ecstasy and presence in all aspects of our world. Here we use the understanding of the erotic life held by Christian mysticism, which is broader than the common use of the term which reduces it to sexual desire alone. The erotic life is our life of deep desire, including our instinctual cravings for food and water, our sexual longings, our drive to create beauty and art, and our refined compassionate desires to serve the good of others and the planet. This erotic life is both highly spiritual and deeply physical. Yet even its spiritual expressions lose all meaning in a world of changelessness and pure potentiality.

Although we won’t go into details here, the relationship between Tantra and Vedanta is actually quite complex (even Adi Shankara himself had a tantric side!). Tantra, like Vedanta, asserts that reality is composed of being (sat), consciousness (chit), and bliss (ananda). Yet whereas Advaita Vedanta sees Satchitananda (being-consciousnessbliss—divinity or the Godhead) as pure nonevolving spirit, Tantra affirms an eventual identity between matter and spirit. Tantra understands Satchitananda as expressing itself as Shiva-Shakti, the divine couple locked in a perpetual loving embrace, who cannot be separated or considered independently of one another. Shiva—the masculine principle—is potential, the absolute, pure unembodied being, spirit; Shakti—the feminine principle—is action, creative power, process, and manifestation, including matter and the processes of our minds and hearts.

Therefore, from the tantric perspective, pure being that does not have the power to become is only a half-reality. In tantric yoga, our goal is not to escape from the world of causation or dissociate from it, but to transform desire, to harness the energy of desire (eros) so as to experience fully the dynamic interplay between Shiva and Shakti and to come to know their unity: “Therefore perfect experience is the experience of the whole—that is to say, of Consciousness as Being and Consciousness as power to become. It is only in the relative world that Śiva and Śakti are thought of as separate entities.”2

In most schools of tantric thought, becoming and evolving are not illusory; they are real. The world we touch and feel is not illusory; it is real. And our lives of willing, feeling, thinking, and loving are not illusory; they are real. The emergence of a baby bird from an eggshell, the cascade of an avalanche, the first kiss of young sweethearts, the implosion of a dying star are all real. Our human breakthroughs and inventions and heartbreaks, our cries of ecstasy and pain, are all real. All these examples point to the nature of Satchitananda as much as That which is pure potential and limitless spirit. This is so because maya is understood differently in tantric thought. In the Tantras, maya is the veil of false polarization through which we mistakenly see Shiva and Shakti as separate from one another. Therefore, the illusion we must overcome is not our investment in the world and its creatures but rather the psychic habit of ascribing ultimate status to pairs of opposites when there is in actuality a unified, nondual dynamic reality. Maya, in Tantra, is the act of “splitting” the whole and creating dichotomies. Left to our own devices, we will do this with almost all of our experience by the time we reach childhood.

We can create all sorts of pairs that seem to be at odds with one another, or placed in a hierarchical arrangement, but are really parts of a whole. Tantra’s critique of Vedantic thought is that it falls prey to just this type of splitting, with spirit being more real than matter and changelessness being more real than process. From this understanding, it’s a short leap to claiming celibacy as a higher calling than sexual activity, or that an unperturbed affect can inhabit the divine heart more than an emotional landscape of mountains and valleys. From the viewpoint of Tantra, even these pairs are not, ultimately, opposites at all but partners that are inseparable and point together to a single reality: Satchitananda, the Ground of Being, expressing itself as Shiva-Shakti, the divine embrace. Tantra affirms every aspect of our world and every facet of our experience, leaving nothing behind in the journey. As the Tibetan tantrika Anagarika Govinda writes,

Thus, good and bad, the sacred and the profane, the sensual and the spiritual, the worldly and the transcendental, ignorance and Enlightenment . . . are not absolute opposites, or concepts of entirely different categories, but two sides of the same reality.3

In tantric thought even maya itself both creates the illusion of polarization and provides the means by which such an illusion can be overcome.4 The same can be said about time: it is both bondage and the means out of bondage.5 The reality of our ever-changing, process-driven world means that the evolving human person, too, is real. The intellectual, emotional, and embodied aspects of our consciousness serve as the raw material by which we, together with the grace of God, learn to navigate the dimensions of consciousness that compose our world.

The energies within us and about us that can draw us away from our center in Satchitananda and lead us into ignorance (avidya) or sin (separation from God) become the very aspects of our experience through which we draw closer to the Divine resident in our own holy center. The “outward” energetic current is transfigured into an “inward” energetic current through meditation, ritual, and other spiritual practices. This is why some have said that the tantric path is a path of sublimation rather than a path of negation.6

Tantra validates the multifaceted nature of our world and gives value to our everyday experience, but Tantra is not a form of materialism7 nor is the idea of transcendence absent from tantric spirituality: in fact, transcendence is quite important in Tantra. Tantric transcendence is a holistic, intrapsychic event that engages and informs our experience of Shiva and Shakti joined as one—potentiality and actuality, being and becoming, spirit and matter. For the tantrika (the tantric practitioner), the liberating experience comes through reconciling all these pairs of opposites and moving beyond such polarizations altogether. Rather than overcoming suffering through a negation of the world of process or dissociating from it, the tantric adept overcomes ignorance and the sense of separation through discovering that all already is Shiva-Shakti: this world is contained within the other world. The tantric path is a path in which nothing is left behind. All serves the unfolding of the Divine in our consciousness and in our world.

And so this tantric transcendence is not an escape from the world of embodiment and its workings or a personal repression of its energies within us. It is not a preferential engagement with Shiva in the absence of Shakti. Using Christian language, we can approach tantric transcendence through the lens of being in the world but not of the world, as when Jesus said: “Be of good cheer; for I have overcome the world!”8 while remaining deeply engaged in his world. Because of its emphasis on the reality of the world of change, “Tantra does not regard action to be diametrically opposed to wisdom, as is the doctrinal stance of Advaita Vedanta, for instance.”9

Our embodied psychic life (including the intellectual, the imaginal, and the emotional) as well as our spirit-filled physical life (including the sexual, the metabolic, and the instinctual) are all potential mediators of divine encounter rather than hindrances to liberation. All the changing elements of our world—the winds, the oceans and rivers, the seasonality of our ecosystems, the plants and animals that are born and die—are part of Shiva-Shakti: all are real, all are potential channels of the numinous, and all are possible partners in tantric transcendence.

Like worldly people, O Lord, may I thirst more for sense objects, But may I see them as your body, without any notion of difference!10

Another characteristic of the tantric understanding of reality is its holographic nature, meaning that the macrocosm is contained in every microcosmic aspect of the world, and so our microcosmic experiences speak to the nature of the macrocosm. The Paratrishika Vivarana Tantra, a commentary on the Paratrishika Tantra by the Kashmiri philosopher and mystic Abhinavagupta (950–1020 CE), gives us a simple formulation of this profound tantric truth: sarvam sarvatmakam (everything consists of everything else). This means that the outer and inner worlds reflect and influence one another. The insight of sarvam sarvatmakam leads to the realization that what happens in the outer world of matter and change affects our spirits, and what we do “inside” has effects in the world. Thus ritual, prayer, and yoga all have practical benefits beyond the individual, and their benefits spill out into the entire cosmos.

As the great Christian St. Seraphim of Sarov has said, “Seek your enlightenment and thousands around you will be saved.” This is not an excuse for quietism or reclusion, but rather a statement that each small microcosm, such as the fist-sized heart of Seraphim of Sarov, can contain the Cosmic Christ, who is all of reality. This holographic nature of the universe, another facet of a tantric understanding of the world, explains how the Christian mystics (tantric masters) of Mount Athos can talk about Christ being enthroned in the human heart. We turn now to the fundamental roots of the Christian worldview, exploring its relationship to the tantric understanding of reality.

THE CHRISTIAN SENSE OF THE WORLD

Tantra affirms that our bodies, our emotional and intellectual selves, and the narrative of our lives are all real and can serve as vehicles of the sacred. Shiva (spirit, changeless consciousness) and Shakti (consciousness-in-process, including matter) are both real and are ultimately one, being two faces of the one Godhead, Satchitananda. We have seen that this tantric view stands in opposition to the classical Advaita Vedantic view in which prakriti (Shakti’s manifestations and processes) is seen as unreal, as illusion (maya). In this latter view, Shakti is illusory and only Shiva, the Absolute, the Changeless, is real.

Christianity, too, has had thinkers who resonate with the Advaita Vedantic and the tantric perspectives. As is true today, in the early centuries of Christianity there was a great diversity of theological thought and spiritual practice among followers of the way, as the early Christians called themselves. Beginning as a sect of Judaism, most of these early Christian groups affirmed the goodness and reality of the world, seeing the material world (including the human body and human psyche) as the handiwork of God. In the first creation story of Genesis (the first book of the Bible), we hear in mythopoetic form how God creates ever more complex levels of being over time. Beginning with light and darkness, God creates sea and sky and then dry land, which later brings forth vegetation. After each advance in the evolution of Earth, the author tells us, “God saw that it was good.” Through this creative process, living beings arise, creatures with soul (Hebrew: nephesh). Nephesh includes emotion, willpower, and mental activity; it includes eros, the life of desire.

The culmination of God’s creative process in Genesis is the human being: “So God created humankind in his image, in the image of God he created them; male and female he created them.”11 Finally, God the Creator together with the heavenly council (the “us” in God’s language in Genesis) looks upon all of creation, including the embodied human person, who has been lovingly made. The author of Genesis tells us that “God saw everything that he had made, and indeed, it was very good. And there was evening and there was morning, the sixth day.”12

Sourced in such an understanding of creation, it would be natural for early Christians to affirm the reality and the goodness of the world. In fact, “[n]othing is more central to Christianity than its affirmation of the sacramental significance of material reality.”13 This world of change and process, which includes joy and sorrow, birth and death, spirit and matter, is ultimately good according to the Hebrew scriptures that formed the early Christians. It is from this understanding that Irenaeus, a Christian bishop and theologian living only a few generations after Christ, says that

[t]he glory of God is the living human person; the life of the human person is the vision of God.14

Irenaeus is saying that the entire living person, the entire human life, is related to the vision of God. Irenaeus does not throw out the changeable or the physical; he sees life, which is activity and change, to be the vision of God. In the Gospel of Thomas (which some suggest may be the oldest extant gospel), Jesus tells his disciples, “If they ask you, ‘What is the sign of your Father in you?’ say to them, ‘It is movement and repose.’”15 The Father—like Satchitananda—is both Shakti and Shiva, both nature and spirit. In the same gospel, Jesus clearly affirms a tantric perspective that the present world and the Kingdom of God are not different realities:

[Jesus’s] disciples said to him, “When will the kingdom come?” Jesus said, “It will not come by waiting for it. It will not be a matter of saying ‘here it is’ or ‘there it is.’ Rather, the kingdom of the Father is spread out upon the earth, and [people] do not see it.”16

Samsara is nirvana. This understanding is analogous to Jesus’s “mission statement” as we hear it in the canonical (biblical) gospels, that the time has come and that the kingdom of God is at hand. Jesus’s core message was not to escape the material realm but was rather a call to “repent” (literally, to “change one’s mind” or undergo a deconstruction-reconstruction process) here and now and believe/experience the Good News. What was the Good News? That the kingdom of the Father is spread out upon Earth! As we would expect, given his cultural and religious environment, Jesus understood the spiritual world to be related to the material world (as well as to the social and political worlds).

St. Paul in his letter to the early church in Rome also expresses a tantric understanding of creation. He clearly sees the created order, the material world, as part of God’s continuing plan of evolution and bound up with embodied human transformation:

For the creation waits with eager longing for the revealing of the children of God . . . We know that the whole creation has been groaning in labor pains until now; and not only the creation, but we ourselves, who have the first fruits of the Spirit, groan inwardly while we wait for adoption, the redemption of our bodies.17

However, some early Christian groups did not accept the creation story of the first chapter of Genesis. Christian groups now categorized as Gnostics (back then, to be fair, they were just other Christians) adhered to alternate creation stories that were highly influenced by the Neoplatonic philosophy that was popular in the Mediterranean world at that time. Much of our information about these groups comes from Irenaeus, quoted above. He tells us that these groups believed that the world was not created by the Godhead but by an ignorant or in some cases evil artisan, the demiurge. This demiurge is antagonistic to God, and although his mother is Sophia (like Shakti, the dynamic wisdom of God), he is unaware of Sophia, and so is devoid of wisdom and blind to matters of the spirit.

For these Gnostics, the material world was a mistake. They believed that by creating the material universe, the demiurge has trapped the sparks of the Divine in the heavy morass of matter. The goal of the Gnostic practitioner was to escape from this evil material world and return to the world of changeless spirit. Much like the Vedantins, they sought to release the “spark” or atman from its material prison and return it to its true (and purely spiritual) home.

The elaborate cosmologies and mythologies of the Gnostics seem strange and exotic to us today. However, their influence continues into our own time, and every now and again gains a foothold in our thinking. As one example, a new use of the term rapture began in the 19th century, in which certain isolated verses in Paul’s letters or the Book of Revelation were interpreted in ways contrary to ancient Christian tradition. What we now call rapture theology was born, offering a Gnostic worldview in a new form. According to this theology, those who have been faithful believers will be taken up into heaven, away from Earth, at some point before, during, or after a period of great tribulation coming in the future. Those not taken up are “left behind” to struggle with the Antichrist and may or may not end up among God’s chosen saints.

Earth, in this scenario, is a place from which one hopes to escape, as it is little more than a bloody battleground in the final conflict between good and evil, after which it will be destroyed. This vision is a new Gnosticism: our true home is supposedly not here on Earth but elsewhere, and our true identity is understood as a disembodied entity, not as a human person. If we hold such a worldview, any concern for the environment, for other living beings, or for one’s own body makes little sense. In the world of rapture theology, issues such as escalating ecological damage, the extinction of species with the eradication of the rain forests, and the pollution of the air and seas are of no account.

Happily, this strange science-fictive account of the end times has little to do with the more world-positive understanding through which the early church read St. Paul and the Book of Revelation. For much of Christian history, Christians believed that many of the events pointed to in the mythic poetry of the Book of Revelation had already occurred. Most theologians today understand the “already and not-yet” reality pointed to in Revelation to be something quite different from what has been fabricated in various rapture theologies. When we look at the Book of Revelation in an unbiased way, we find that in the grand conclusion of its fantastic story the New Jerusalem breaks into our world, descending to Earth: spirit and matter, Shiva and Shakti, husband and bride, become one, and the place this happens is nowhere but right here:

I saw the holy city, the New Jerusalem, coming down out of heaven from God, prepared as a bride adorned for her husband. And I heard a loud voice from the throne saying, “See, the home of God is among mortals. He will dwell with them; they will be his peoples, and God himself will be with them.”18

These eschatological understandings, one Gnostic and one Scriptural, provide Christian parallels to the overcoming of illusion (maya) according to Advaita Vedanta and Tantra, respectively. In the rapture fantasy, we see an escape from the material world. Only the unblessed are left to remain in this sad world of change, challenge, and embodiment. For those “taken up” in the rapture, the illusion of the world has been overcome, the mortal coil has been shuffled off. They have become pure spirit, timeless, enjoying the presence of the Absolute, of Shiva alone. In the scriptural picture, the descent of the New Jerusalem to Earth is a picture of overcoming the illusion of the separation of Shiva and Shakti. God dwelling among human beings, the heavenly city present here on Earth, point to the tantric understanding of the nondual nature of Shiva-Shakti. According to Tantra, as according to scripture, it is the illusion of the separation and disunity of Shiva and Shakti, or of heaven and Earth, that we must overcome.

The scriptural accounts of the Ascension of Jesus, too, are often misread as a rapture-type experience. In the gospels and in the Acts of the Apostles, we are given the picture of Jesus being taken up into heaven. Tradition has placed this event as occurring forty days after the Resurrection (forty being a number associated in the Bible with transformation or completion of a cycle of growth). Coming from our own worldview and context, this seems to be a picture of Jesus going away. However, for the 1st-century readers of the scriptures, the meaning would be quite different. In the ancient “layer cake” universe of Jesus’s time, the Ascension of Jesus was a pictorial way of describing his permeation of all reality. Jesus does not go away into heaven, because heaven (the “top layer” above Earth, the “middle layer” of the cake) is understood to be the ground of being that informs and imbues all of reality, including earthly reality:

Jesus in his ascended state is not farther removed from human beings but more intimately connected with them. He is the integral ground, the ambient wholeness within which our contingent human lives are always rooted and from which we are always receiving the help we need to keep moving ahead on the difficult walk we have to walk here. When the eye of our own heart is open and aligned within this field of perception, we recognize whom we’re walking with.19

In the biblical Letter to the Ephesians, the author explains this very succinctly: “[Christ] who descended is the same one who ascended far above all the heavens, so that he might fill all things”20 (italics mine). As one old Christian prayer says,

There is no plant in the ground

But is full of His virtue;

There is no form in the strand

But is full of His blessing. 21

The Christian tradition, both in scripture and in later writings and patterns of life, affirms the reality and goodness of the world. Christianity’s view of reality is a tantric view, analogous to seeing Shiva and Shakti as two faces of the same reality. Earth and the New Jerusalem are, ultimately, one. Creation therefore is essentially good. As followers of the way, as Christians and as tantrikas, we are called to engage the world, not to escape from it. The goodness of all orders of being—the whole creation—means that genuine Christian spirituality involves negotiating our pain and difficulty in this world of finitude and process through understanding that “samsara is nirvana,” that the New Jerusalem is here. In the Gospel of Thomas, Jesus speaks as the Shakti of God, the divine presence informing and inhabiting all things:

It is I who am the light which is above them all.

It is I who am the all.

From me did the all come forth, and unto me did the all extend.

Split a piece of wood, and I am there.

Lift up the stone, and you will find me there.22

The poets and theologians of the Eastern churches, such as Ephraim the Syrian, were particularly strong in their affirmation of the goodness of creation. The same can be said of Celtic Christianity, which bears a direct link to the churches of the East. The great Celtic theologian Pelagius (4th century) wrote about the wonder of creation in a letter to a friend.

Look at the animals roaming the forest: God’s spirit dwells within them. Look at the birds flying across the sky: God’s spirit dwells within them. Look at the tiny insects crawling in the grass: God’s spirit dwells within them. Look at the fish in the river in the sea: God’s spirit dwells within them. There is no creature on earth in whom God is absent. . . . Look too at the great trees of the forest; look at the wild flowers and grass in the fields; look even at your crops. God’s spirit is present within all plants as well. The presence of God’s spirit in all living things is what makes them beautiful; and if we look with God’s eyes, nothing on the earth is ugly.23

In the everlasting patterns of Celtic Christian art, “used to suggest the eternal interweaving of heaven and earth, time and eternity,”24 we see the harmony between the tantric, Earth-positive Christian message and its own pre-Christian inheritance of druidic nature mysticism, which served as an “Old Testament of the Celtic Church.”25 Celtic theologians such as John Scotus Eriugena (9th century), joined by Continental mystics and theologians with historical roots in Celtic spiritually such as Hildegard of Bingen (12th century) and Meister Eckhart (13th century), understand the physical and changeable world in a way similar to Eastern Tantra.

Eriugena tells us that God is in all things, the essence of life; God has not created everything out of nothing, but out of his own essence, out of his very life. . . . The world, therefore, Eriugena regarded as theophany, a visible manifestation of God.26

And from the lands of the Holy Roman Empire, Eckhart has this to say: “Being is God’s circle and in this circle all creatures exist. Everything that is in God is God.”27 In saying this, Eckhart does not mean that “everything that is” equals God. While everything that is exists in God and is God, God is more than everything that is. If we simply equate God with the world, we lose the erotic (in the wide sense) allure of what is beyond the horizon, and negate the divine presence that undergirds and overarches reality and serves as the source and goal of our deep longing. The world is God, and God is more than the world.

The understanding of God’s relationship with creation that we find in Eckhart, Eriugena, and other Christian mystics differs considerably from what has become the dominant Christian view, which largely divorces creation from God’s own identity, accomplishing something akin to a separation of Shakti from Shiva.

A SHOOT FROM THE FIRST ROOT

Tantric Ritual and Christian Sacraments

As one example of the application of our first Root of Tantra, let us look at how the world of time and causation being not-two with the world of spirit plays out in tantric ritual, whether that ritual occurs in a Hindu, Buddhist, or Christian context. If the corporeal world is holy and good, not other than but part of the world of spirit, then the things of the world can serve as doorways and aids in worship, rather than being seen as “idols” or distractions. Tantra, then, lends itself to kataphatic (image-expressive) spirituality and rich symbolic worship, what Christians might call liturgical or high church worship, both in its interior and exterior aspects.

In the East we find a strong focus on the human body in tantric rituals. One of the first aspects of tantric ritual involves nyasa (placement), by which the tantrika purifies and sanctifies her or his body through assigning different deities and powers to the various parts of the body in elaborate and expressive ways. “By means of nyāsa, Tantric practitioners sanctify and simultaneously ‘cosmicize’ their own body . . . the bodily microcosm enshrines within itself the entire macrocosm, because everything that exists comes out of the same One.”28 This process of purification is important to Eastern tantrikas because they will ultimately invite a chosen deity into their bodies.

In Christian practice we see a similar if less elaborate process. Traditionally, upon entering the church the Christian worshipper would bless him- or herself with the sign of the cross*4 (which, as we shall see later, marks and activates the main energy plexuses of tantric physiology), perhaps using holy water to do so. The worshipper may then approach various icons or images and pray before them, perhaps making bodily prostrations, kissing the images, or lighting candles, or simply (if in the West) kneeling to pray. In these ways, the Christian worshipper also sanctifies and prepares the body for full participation in the central rite, which likewise involves the invitation of the chosen deity into the body, an entrance of the macrocosm into the microcosm: the reception of Holy Communion, which we shall look at in detail later in this book.

The Kula Arnava Tantra (15.46) promises that the practice of nyasa creates an “armor” that fends off all obstacles, putting them to flight. This understanding of nyasa resonates with St. Paul’s exhortation in his Letter to the Romans (13:12b, 14a) to “put on the armor of light . . . put on the Lord Jesus Christ.” In his Letter to the Ephesians (6:11a, 12b–17), Paul comes even closer to something like tantric nyasa as he equates various body parts with particular virtues:

Put on the whole armor of God, so that you may be able to stand against . . . the rulers, against the authorities, against the cosmic powers of this present darkness, against the spiritual forces of evil in the heavenly places. Therefore take up the whole armor of God, so that you may be able to withstand on that evil day, and having done everything, to stand firm. Stand therefore, and fasten the belt of truth around your waist, and put on the breastplate of righteousness. As shoes for your feet put on whatever will make you ready to proclaim the gospel of peace. With all of these, take the shield of faith, with which you will be able to quench all the flaming arrows of the evil one. Take the helmet of salvation, and the sword of the Spirit, which is the word of God.

Sarvam sarvatmakam, everything composed of everything, speaks to another way of engaging Christian sacraments. The liturgical churches recognize seven (or in some cases, two) Sacraments, defined by St. Augustine of Hippo in the 5th century as “an outward and visible sign of an inward and invisible grace.” According to the official catechism of the Roman Catholic Church, “[t]he visible rites by which the sacraments are celebrated signify and make present the graces proper to each sacrament.” Similarly, Martin Luther famously said that “[a] sacrament consists in the combination of the Word of promise with a sign,”29 and in another place states that a sacrament is “a divine covenant of grace and blessing transmitted in the visible form.”30

Here we clearly see an affirmation of our first root of Tantra from both Roman and Protestant sources. Spiritual grace and knowledge not only can be signified fruitfully by actions and things of this world, but ought to be for the most healthful—sacramental—experience of such grace and enlightenment. The outer and the inner, the material and the spiritual, work together symbiotically for the transformation of the human person. As Episcopal priest Cynthia Bourgeault says, reflecting on Augustine’s definition of sacrament, “this definition does not make sufficiently clear . . . that a sacrament does not merely symbolize a spiritual reality; it lives that reality into existence.”31 She asserts that “[a] sacrament reveals a mystery in a particularly intense way while at the same time offering the means of its actualization.”32

In Asian Tantra, the exterior aspects of worship can be quite elaborate. A highly developed tantric iconography exists in India and Tibet, where the figure of the divine couple in perpetual embrace often forms the crux of the image. Images of tantric deities are used in worship, where the presence of the deity itself is called down into the image so that it can form a local energetic portal to the deity itself. Likewise, adepts in Tibetan Tantra typically handle ritual tools such as the vajra (diamond scepter or thunderbolt, representing Shiva energy) and the ghanta (bell, representing Shakti energy) in worship, each designed to particular specifications. In the most sensory and elaborate Christian liturgies, those of the Eastern Orthodox Churches, the priest also handles sacred tools such as small golden spears and spoons when preparing and administering the Bread into which has been invited the Real Presence of Christ.

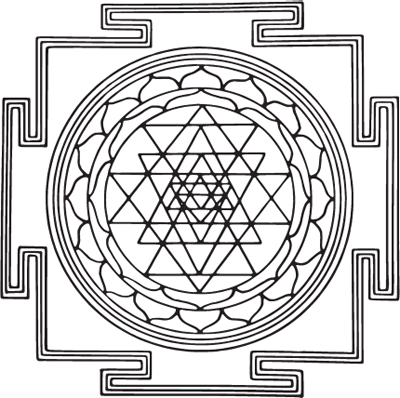

In addition to images of the Shiva-Shakti embrace, Eastern Tantra has developed a highly elaborate visual language of mandalas and yantras. These diagrams are spiritual landscapes of sorts, the more pictorially expressive mandalas illustrating multiple, concentric levels of consciousness, with the “palace” (vimana) at the center. This palace represents the deity ruling the mandala, and therefore a particular aspect of higher unitive consciousness. The mandala illustrates the path toward tantric actualization. The more geometric and simple yantra typically portrays the central palace itself, often with a single dot (bindu) in the very center, representing the Source, the Ground of Being (Satchitananda, Godhead).

Figure 2.1. The Sri Yantra, the womb of reality (image by N. Manytchkine)

In Christian practice, we find some interesting parallels, such as the mandala of the symbols of the four gospel writers (ox, lion, eagle, and human) arranged similar to the four “gates” of a yantra, representing the gospels as the living gateways to the center, Christ. Patterns similar to Eastern mandalas or yantras are often superimposed onto or into the body in Christian mysticism, such as in the Interior Castle of St. Teresa of Ávila. Here the aspirant is led concentrically through various moats, gardens, and chambers to the “palace” where the living Christ sits enthroned at the center of the person.

Juxtaposing Teresa’s description with the cosmic mandala provides a perfect example of sarvam sarvatmakam, the holographic nature of the tantric universe: the microcosm (the psychic and spiritual life as described by St. Teresa) mirrors and contains the macrocosm (the effusive cosmologies of Tantra illustrated in mandalas). We see this inner-outer dialogue played out in the Christian practice of walking a labyrinth. The winding paths of the circular labyrinth literally put the individual within the symmetric circular pattern of a mandala, inviting the walker to physically (and spiritually) move to the center.

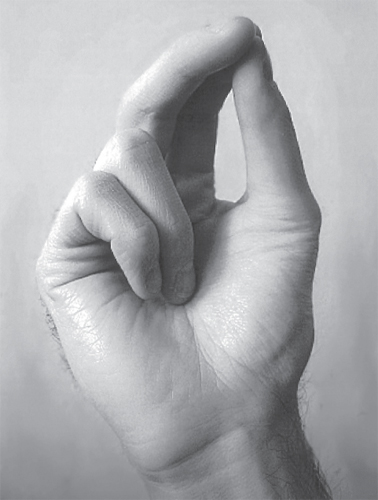

Both Eastern and Christian Tantra make use of hand gestures (mudras), which symbolize and activate within the worshipper certain states of consciousness or spiritual realities. The vocabulary of mudras has been greatly developed in the East, with very many mudras known and practiced in various traditions.

In Christianity, only two are prevalent today: the mudra of Christ blessing and the mudra for making the sign of the cross. For the Christ blessing, the fingers of the right hand form the Greek letters XP (chi rho), which are the first two letters in the Greek word Christos, or Christ. In the simpler mudra used in making the sign of the cross, the thumb, index finger, and middle finger of the right hand are extended and brought together to a point at their tips to symbolize the Holy Trinity as one, while the ring finger and pinky are curled down into the palm of the hand, representing the nature of Christ (and of the divinized human being) as both human and divine. This mudra is also known in Indian Tantra, where it is called kubera mudra (the mudra of abundance).

Broadening out from these particulars, we can say that in the rites of Eastern Tantra as in liturgical Christian worship, there is a sense of both anamnesis (re-creation of the memory or state of being one seeks in the present) and eschatological sign (the anticipation here and now of our—and the world’s—final divine state).33 Each of these realities is instantiated into the consciousness of the adept through the manipulation of prakriti—both in terms of material objects and in terms of inner focus, energy work, and mantra. Yet in Eastern traditions as well as in Christianity, there are schools of thought that are opposed to liturgical rites, believing that such worship is regressive or distracting to the practitioner or somehow impure.

Figure 2.2. The mudra used by Orthodox Christians to make the sign of the cross (photo by Adriatikus)

Such iconoclasm can typically be traced back to a view of the world similar to Gnosticism, at least in sentiment if not in overt philosophy, in which matter cannot effectively serve as a conduit for the spirit and where aspects of consciousness aside from the rational—such as the aesthetic, erotic, and emotional—are suspect in the holy house. This is, of course, opposed to the tantric insight of Shiva-Shakti. Often disguised as an “advance” beyond a supposedly superstitious ritualism, such movements call for unadorned, minimalist worship spaces and largely unembodied worship practices devoid of ritual actions or sensory stimuli. Such iconoclastic movements, from the perspective of Tantra, strip away from the worship experience much of the potential power for transformation and could be likened to pushing an automobile instead of using its combustion engine.

The famous Zen scholar and teacher Alan Watts wrote Behold the Spirit: A Study in the Necessity of Mystical Religion in 1947 while he was still an active Episcopal priest. There he says:

On the whole . . . it is probably safe to say that it impresses [the modern person] as less awkward when the form of worship is very frankly archaic and symbolic. It may still seem unreal and remote from life, but this will only be true so long as the Church fails to complement symbolic religion with mystical religion. . . . It is highly probable, therefore, that as the mystical understanding of Christianity increases, as union with God is realized more and more in everyday life, our forms of worship will become unashamedly archaic and symbolic. We shall keep the ancient symbols of the Christian religion in all their original purity, for our spiritual progress will not consist in a development and adaptation of symbolism, but in an increased understanding of its meaning.

Georg Feuerstein underlines the practical aspect of ritual worship: “The numerous observances and formalities that are integral to the Tantric path are intended to stabilize the practitioner’s mind and fortify his or her will.”34 Embodied ritual serves to create a healthful, safe path that the consciousness of the adept travels along toward higher states of realization. It is not hypnotic but rather a tool for true wakefulness. At their best, such ritual practices, whether in a Hindu or Tibetan Buddhist or liturgical Christian context, are not markers of superstition or fetishism but serve as a doorway into a landscape in which the awe-inspiring divine presence can be experienced with a minimized sense of danger, and transformation can occur on all levels of one’s being. Now we turn our attention to that very transformative power of God, Shakti as the divine activity of God in the world and in our lives.