Kevin Tan, a 1990 graduate of the School of Architecture at the National University of Singapore, is a gifted designer. He had his training at a time when the department was nurturing a specially talented cohort of students. He gained experience of international practice with Llewelyn Davies (now Llewelyn Davies Yeang) in London and P&T (formerly Palmer and Turner) in Hong Kong. In his final year, his tutor was the author of this book, to whom he attributes an appreciation of design in the urban context. He also gained insights from the Thai architect Mathar Bunnag,1 who taught him ‘to think out of the box and return to first principles’, and warmed to the environmental consciousness of Dr Suthipanth Sujarittanonta, another Thai academic teaching at the National University of Singapore.2

Tan had the immense good fortune to come under the influence and guiding hand of Ernesto Bedmar, who was at that time an external tutor in the School of Architecture. Soon after graduating in 1990, Tan joined the Argentine-born Bedmar’s design-orientated practice and honed his compositional skills under the architect’s mentorship before leaving some ten years later, in 2001, to set up his own firm.

Tan frequently refers to the influence on his work of the early modern masters, perhaps to distance himself from any nostalgic references to tradition and possibly to affirm, as with most Singaporeans born after independence was achieved in 1965, that he is of a generation with little attachment to the past and who are generally orientated towards a future with a global outlook. He insists that his designs have always been ‘pure modernism’ and that he has ‘never wished to indulge in vernacular tradition’. Tan lists his primary influences as the early modern masters, particularly Louis Kahn for the timelessness and serenity that he brings to his buildings. He also admires a number of contemporary architects, including Norman Foster for the clarity he brings to his work, Renzo Piano for his craftsmanship and Herzog & de Meuron for their freshness and bravado.

Tan combines a ready charm with candour, which enables him to relate well to his clients. Like many architects of his generation, he is in a hurry and his success has bred an aura of confidence. ‘I believe there is a real and practical brief for each house,’ says Tan. ‘There is also an invisible brief which comes through conversations and observations. I have been fortunate to encapsulate this unspoken brief sometimes more successfully than others.’

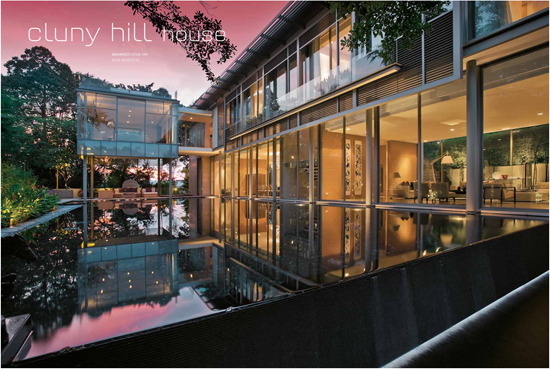

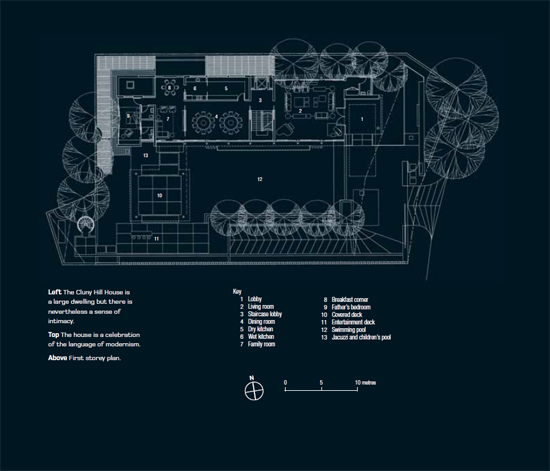

The Cluny Hill House is unashamedly modern, employing masonry, metal and glass cladding on a concrete frame in a strictly orthogonal composition. The L-shaped ground floor is remarkably transparent, with living and dining spaces that face south to embrace a swimming pool. The house is located close to the summit of Cluny Hill and entry is from the east directly into a paved vehicle court. Vehicles sweep down into a basement car park where visitors alight. They first view the house reflected in the pool and then turn north to ascend a short flight of steps to a square portico.

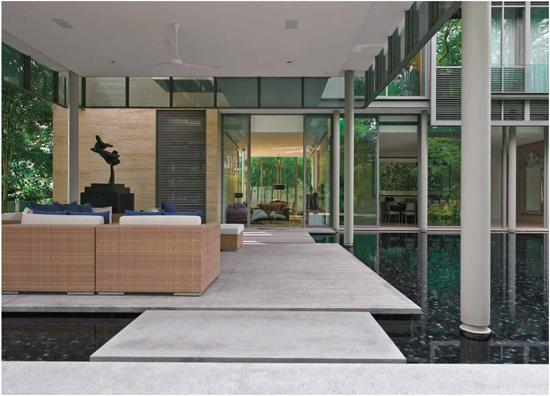

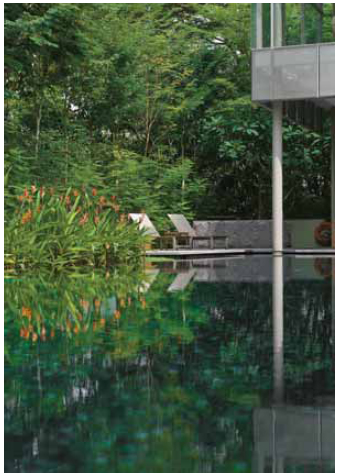

Beneath the master bedroom suite is a shaded deck surrounded on three sides by water.

After pausing to remove their shoes, visitors turn 90 degrees to face west and enter the main reception and living space that looks south over the swimming pool. Thereafter, the accommodation is arranged in linear fashion, with a stair and elevator core followed by the formal dining room for sixteen people. This also overlooks the pool and runs parallel with the kitchen that is located on the north elevation. The plan of the north wing is completed by a smaller sitting room and a study that look south over the pool deck. In the north west corner of the site is a koi pond.

Set at right angles to the north wing is the shorter west wing. Beneath the master bedroom suite, which forms the shorter ‘leg’ of the L-shaped plan, is a shaded deck surrounded on three sides by water. In the southwest corner of the deck are a barbecue stove, a servery and a bar for outdoor entertainment. Above the master bedroom is a landscaped roof deck designed to capture the evening breezes. The Cluny Hill House is a large dwelling but there is nevertheless a sense of intimacy and of connection between the different spaces and activities.

The house celebrates the language of modernism with its orthogonal form, flat roof and first storey raised above the transparent base on circular pilotti. Viewed from the south, it appears to ‘float’ above the pool. Shading devices in the form of horizontal louvres reinforce the modernist tectonics, and the combination of metal, glass and grey concrete completes the aesthetic. Tan sees the house as ‘a fresh modern, sharp yet understated and comfortable house with all the practical needs of a young growing family and live-in grandparents’.

In a relatively short time, Kevin Tan has built up a substantial practice with a series of original and visually compelling designs. A large proportion of the work of aKTa-rchitects is residential commissions, and he is currently working in China, India and the Middle East. The most intriguing commissions are the remodelling of a 100-year-old Victorian dwelling in Kolkata to meet the requirements of a modern Indian family, and a desert oasis dwelling in Dubai.

The Cluny Hill House is a large dwelling but there is nevertheless a sense of intimacy.

The house is a celebration of the language of modernism.

First storey plan.

The house is surrounded by a screen of mature trees and more recent plantings.

The secluded entertainment area and barbeque deck.

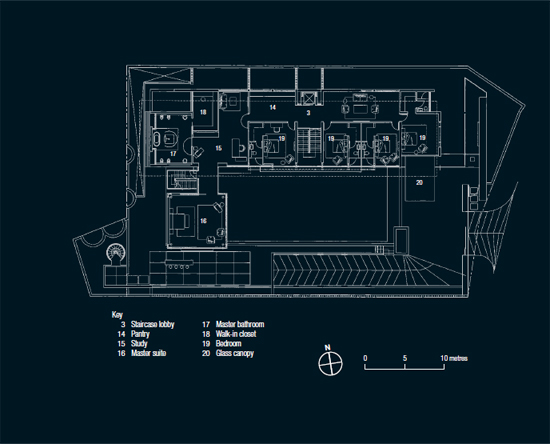

Second storey plan.

A quiet area for calm reflection.

The link to the master bedroom and, on the right, the staircase leading to the roof terrace.

Footnotes

1 Mathar Bunnag is a Thai architect. He graduated from the University of Manitoba with an M.Arch. and went on to complete a Masters in Urban Design at Harvard University. He lectured in the School of Architecture at NUS from 1984 to 1986. In 1988, he set up his own successful practice in Hong Kong and subsequently moved it to Bangkok in 1990.

2 Dr Suthipanth Sujarittanonta taught Environmental Design in the School of Architecture at NUS. He subsequently returned to Thailand and was appointed Dean of the Faculty of Architecture at Sripatum University.