A gallery overlooks the principal living space.

Although formwerkz architects work as a co-operative, the design of the Jalan Sedap House was principally the responsibility of one of the four partners, Gwen Tan, a year 2000 graduate of the National University of Singapore. In her early years she was deeply influenced by the Turkish historian Dr Gulsum Nalbantoglu1 and the notion of narrative architecture, which is considered quite apt for residential design because houses often tell a story.

In her year out, Tan gained practical experience with Ang Gin Wah, a Singapore-based architect who does most of his work in Japan and in Australia where he qualified. Waro Kishi was an occasional visitor to the office and Tan developed an affinity with Japanese architecture. ‘An architect I greatly admire,’ she says, ‘is Kazuyo Sejima whose works tend to have an ephemeral quality and the most beautiful and simple plans. What is admirable is that she made her mark in a male-dominant industry and in a male-dominant society. Her success was inspiring for female architects.’

Tan travelled widely prior to returning to her studies. She was intrigued by the spatial experience of Gaudi’s works in Barcelona and the work of Alvaro Siza. She remarks that ‘Rem Koolhaas, MVRDV and Herzog & de Meuron were the heroes for many of us at that time, principally for exploring new ways that buildings are put together.’

Her mentor in her final year in the Department of Architecture was Associate Professor Bobby Wong Chong Thai, who recalls that her thesis design ‘was cool, with none of the histrionics associated with high architecture. At the time, the architecture of Kazuyo Sejima was still not widely known but Gwen Tan’s work seemed to embody some aspects of Sejima’s aesthetics.2 I don’t know whether this is good or bad, but certainly at the time it was very refreshing.’

The Jalan Sedap House is a major reconstruction of an existing terrace house for a banker. The client’s brief was simple: ‘Every space in the house must fulfil a purpose.’ In effect, the house was designed from the inside out, with intensive interrogation of the function of every square metre. This applies equally to the garden space. This has parallels in the ‘Pattern Language’ approach of Christopher Alexander.3 The result is a very simple plan form that, at the same time, embodies extraordinary complexity. The patterns that emerge include ‘a place for playing the piano’ and ‘a place for watching fish’ that coalesce into a whole.

Take, for example, the guest bedroom. The guest bed is raised high above the floor permitting suitcases to be stored beneath. The space also serves as an open wardrobe with a hanging rail hidden below. The bed is concealed behind a sliding folding door and is accessed by a steep ‘ladder’. When the door is closed, the space becomes a music room with an upright piano beneath purpose-built storage shelves filled with classical CDs. Amazingly, a tree grows through a void in an otherwise redundant corner of the room.

Other ‘patterns’ that emerge are ‘a space for entertaining guests’ and ‘a place for reading and contemplation’. Alongside the entrance is a TV viewing room with banquette seating. It serves a dual purpose, for it can be used to greet visitors or opened out to host a small gathering of friends under the covered carport.

On the upper landing there is a spacious purpose-designed reading chair looking towards what the owner describes as a ‘framed picture’ where the adjacent house is obscured and the owner can observe a horizontal strip of blue sky and a square of green where a tree has been planted. The landing also serves as a ‘gallery’ above the music room, while an L-shaped bay window on the front façade is also customized for the purpose of reading at a different time of day.

But the house is built around and primarily celebrates the owner’s love of classical music. A Singapore President’s Scholar who had dreamed of being a concert pianist but somewhat reluctantly settled for a more pragmatic career in finance, he worked in London for nine years and for one year in Moscow where he took the opportunity in his leisure time to study under a renowned Russian piano teacher. Consequently, at the heart of the house is a double-storey space occupied solely by a grand piano. This is the defining feature of the house, a modern music ‘salon’ where the grandeur of a concert hall is encapsulated in a modest space.

At the heart of the house is a double-storey space occupied by a grand piano.

A window is transformed into a ‘place for reading’.

Another of the owner’s passions is tropical fish, attested to by two huge aquariums. One is located in the ground floor living space but its reverse side can also be viewed within the powder room. The second aquarium is located in the bathroom off the master bedroom suite, so that the first object that the owner’s eyes alight on each morning is the darting movement of numerous exotic fish.

The impression is of a meticulous client and his encounter with an architect bent on providing a unique, personalized solution to his requirements. As Tan explains, ‘When designing houses, we start by dissecting the client’s lifestyle or interests. Like a novel with a narrative that binds it, the individual pieces start to fit into the plan with a purpose.’ What transpires is a brilliant piece of bespoke design ‘tailored’ exactly for an individual who has a clear notion of what the important things are in his life. He is a very organized individual with clear priorities, described by the architect as a perfectionist. The plan and section are the result of a complex interweaving of the client’s requirements.

Referring to some of the challenges of designing a bespoke house, Tan notes that ‘The house had to be climatically controlled by industrial-grade dehumidifiers and a thermostat-controlled automatic heat exhaust due to the very precise and very limited range of temperatures and humidity that the client demanded for his pianos and aquariums. Ironically, the two work against each other; the aquariums produce a lot of humidity, which is bad for his pianos. Hence the inclusion of hidden glass sliding panels that partition the house into different zones for mechanical and electrical equipment, which work independently to achieve the desired results.’

‘For the heat exhaust to work, natural ventilation is needed, even when there is no one at home. Louvred glass panels were therefore incorporated to supply inward airflow. Openings to the west were deliberately kept to a minimum, and where large openings were needed for visual connection to the gardens, there were sufficient overhangs that were not shielded by the neighbour’s house. Air conditioning is available for almost all spaces in the house but is only used when the owner is at home.’

‘Typically,’ adds Tan, ‘houses are designed for a couple or family, but when it’s a single-person dwelling, it opens up new opportunities for spatial planning. The client was very particular about the technical requirements and functionality of the house. He also had very high expectations of the end product as it was intended to “compensate” for his detachment from his close friends in London when, for family reasons, he had to relocate back to Singapore.’

The owner confirms that this is his ‘dream home’, for it embodies all the pleasures that he imagined in a dwelling designed specifically for delight–a garden, reading spaces, aquariums and a piano. The dining room is a small, intimate space overlooking a courtyard, and the tiny galley kitchen reflects the fact that the owner does not place much emphasis on cooking. According to Tan, ‘The house recounts the story of the client’s love for his garden, for nature, for tropical fish, for music and for reading; all are linked together in a form of spatial poetry.’

A guest bed space with a wardrobe space below.

On the second-storey gallery there is an alternative ‘place for reading’.

Light pours into the stairwell through a clerestory window.

The owner’s passion for tropical fish is evident from the two large aquariums incorporated in the design.

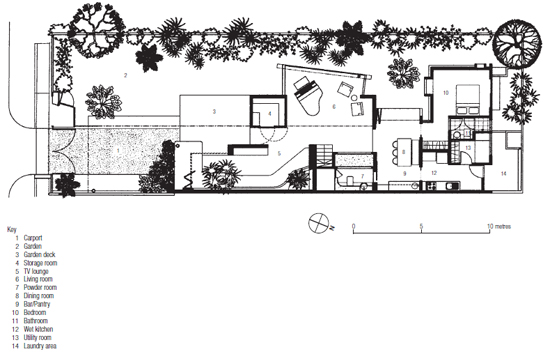

The first storey plan.

One aquarium is located in the living room, with the reverse side visible from the powder room.

A tall window makes a visual connection between the living room and the wider urban context.

The entrance lobby with the TV lounge to the right.

The garden is designed as an extension of the interior spaces.

In the absence of distant views, light enters from above through carefully positioned clere-story windows.

Footnotes

1 Dr Gulsum Nalbantoglu is currently Professor and Head of the Department of Architecture at the Izmir University of Economics, Turkey.

2 Kazuyo Sejima was born in 1956 in Ibaraki, Japan, and graduated in 1981 from Japan Women’s University. She began her career with Toyo Ito, leaving in 1987 to set up her own practice, Kazuyo Sejima & Associates. In 1995, she founded SANAA with Ryue Nishizawa. Among her many projects are several exemplary dwellings in Japan, namely Y-House, Katsura, Chiba (1993), Villa in the Forest, Chino, Nagano (1994), N-House, Kumamoto, Kumamoto Prefecture (1994), S-House (with Ryue Nishizawa) (1996), M-House, Tokyo (with Ryue Nishizawa) (2000) and Small House, Tokyo (2001).

3 Christopher Alexander, A Pattern Language, New York: Oxford University Press, 1977.