Approaching the bamboo screen at the entrance, there is a strong sense of materiality.

A 1997 graduate of the School of Architecture at the National University of Singapore, Randy Chan’s final year mentor was Associate Professor Pinna Indorf. Chan’s thesis, ‘Architecture as Theatre as Architecture’, spoke about the urban phenomenon of persistence of memory that continues to operate in Singapore despite the surrounding urban fabric being torn down. Chan worked for a year as an intern with Tang Guan Bee, in 1994. The following year he won a scholarship to study at Sophia University in Tokyo before returning to the National University of Singapore to complete his studies.

Chan recalls his year out with TANGGUANBEE Architects as being formative. He joined the practice shortly after Ling Hao, whose work is also featured in this book. At the time, Tang Guan Bee was working on the conspicuous Fortradale Condominium at Fort Road, the Bedok Market and the beguiling Gallery Hotel on the Singapore River. ‘I enjoyed Tang’s sense of humour and discussions, often conducted in the Hokkien dialect, which somehow added to the flavour,’ says Chan. ‘It was a good time to be working at TANGGUANBEE Architects and there were many evenings when the staff shared ideas on architecture through slide shows.’

On graduating, Chan worked with the Alfred Wong Partnership, but after three years with the esteemed winner of the inaugural Gold Medal of the Singapore Institute of Architects he moved on to set up zarch collaboratives, in 2000. The Jalan Kampong Chantek House is designed for the family of a neurosurgeon in private practice in Singapore. The house is essentially a two-storey square box with a central courtyard, located on a sloping square site. That simple description belies, however, the immense complexity of the architectural composition. Chan has first rotated the box so that triangular spaces are created at each corner of the site. Then he has sliced off the northwest corner of the cube and attached a similar volume to the southeast corner. Suddenly, all manner of spatial opportunities are apparent. The site does not offer any distant views and, consequently, the plan is focused on the peripheral spaces within the perimeter and inwards to a square central courtyard that serves as both a lightwell and an airwell. ‘The clients wanted a house where every space was able to relate to the exterior,’ says Chan. ‘This explains the central courtyard and the external spaces. He and his wife also wanted the house to have an “earthy” palette of materials.’

An outdoor bathroom is located adjacent to the six-mat tatami room.

The entrance lobby and living space.

A waterfall cascades down the inclined roof over the reception area.

First storey plan.

The bamboo screen at the entrance acts as a concealing and protective veil.

The lap pool runs parallel to the eastern boundary.

Bamboo groves line the western and northern boundaries of the site.

The reception area and music room.

Approaching the dwelling along a narrow drive from the southwest, a gentle ramp gives access to a random-paved pathway and hence to a timber bridge across a koi pond. A ‘veil’ composed of vertical timber slats on the left and bamboo poles on the right partially conceals the entrance foyer. Turning sharply right on entering, a short flight of stairs leads to a raised triangular reception pavilion.

Turning again, this time through 180 degrees, is the living room that adjoins the central court. The double-storey space has a sunken sitting area accommodating a grand piano. The other rooms on the ground floor are related to the central courtyard: a formal dining room, a guest suite with access to an open-to-sky bathtub and a five- tatami mat meditation room. There is also an entertainment room with an attached wine cellar, wet and dry kitchens and the maid’s quarters. The orientation of the cube permits southwest and northeast monsoon breezes to flow through the house. The central court also assists in natural ventilation.

The second storey is similarly organized around the courtyard. The master bedroom suite, a child’s bedroom and the family hall and library each have one wall adjoining the central void. A gym, a Jacuzzi and a spa garden attest to a sybaritic lifestyle, an antidote to the frenetic pace of Singapore.

In the design of the external spaces, Chan has created an attractive garden that flows around the perimeter of the site and offers a multitude of spatial experiences. From the entrance of the house, the garden, linear in form, extends along the western boundary in combination with a mixture of random and orthogonal paving. Upon reaching the northwest corner, it assumes a triangular shape, where a tea room sits prettily beneath a tree house. A skeletal circular staircase amidst the western garden ascends to a rooftop terrace.

The northern garden also extends in a linear manner along the boundary, with timber decking skirting the obligatory yard, leading to a grove of bamboo trees in the northeast corner of the site. Turning once again, a 25-metre lap pool runs parallel with the eastern boundary alongside an extension of the timber deck. A lotus pond, at right angles to the southern end of the lap pool, adds further variety.

The most striking feature of the house is the total integration of the interior and external spaces and the intensity instilled into the design. In this way, the house embraces a rich variety of spatial experiences expertly orchestrated by the architect.

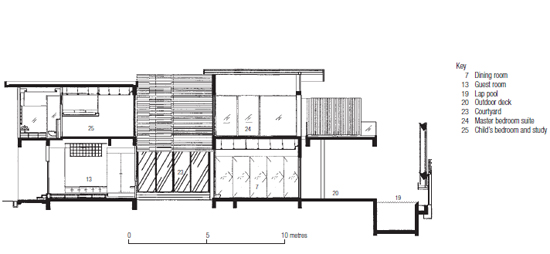

Section indicating the central open-to-sky courtyard that assists in cross-ventilation.

The entrance viewed from the reception area.

Privacy is provided by the bamboo entrance screen.

From the head of the stair, the eye is drawn to the reception area and the raised living area beyond.

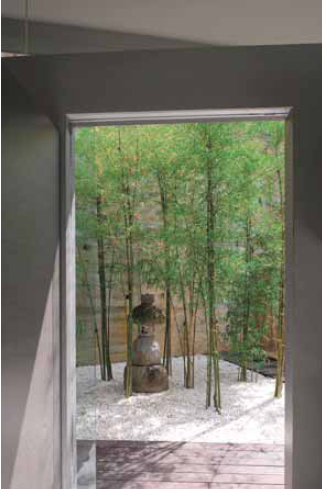

A quiet corner of the bamboo garden–a place for reflection and meditation.

The open-to-sky courtyard at the core of the house.

Detail of the skeletal circular staircase rising from ground level to the rooftop garden.

In the absence of distant vistas, the house turns inwards to courtyards and bamboo gardens.