The bedroom wing is carried on an array of slender, circular steel columns.

Ko Shiou Hee is a graduate of Rice University in Houston, Texas. He gained experience with Morphosis, Kohn Pederson Fox and I. M. Pei in the USA before working in Japan from 1991 to 1993. On his return to Singapore, he worked with A61 for five years, leaving in 2000 to set up K2LD. While in Japan, Ko was introduced, via the work of Hiroshi Hara, to the architecture and writing of Steven Holl. Holl’s book, On Phenomenology, had a deep influence on Ko, and when I reviewed his work in 2000, he quoted a passage which seems relevant to the Landscape House.1

‘Perception of architecture entails manifold relations of three fields: the foreground, middle ground and distant view are united in one experience as we observe and reflect while occupying a space. Merging of these fields of space brackets very different perceptions. In the intertwining of the larger space with its forms and proportions and the smaller scale of materials and details lies architectures power to exhilarate.’

Cluny Hill is an area of large mature trees and lush under-growth. Shiou Hee opines that ‘the stunning landscape called for a dwelling that would “disappear” into its surroundings’. He invokes an expression that is widely associated with Glenn Murcutt’s houses in Australia, which drew upon the aboriginal view that dwellings ‘must touch the ground lightly’.

The house is located in a prominent position on rising ground. It is highly visible yet set back from the road and flanked by two majestic Tembusu trees. An arborist determined that one other Tembusu had to be felled, allowing the main dwelling space on the second floor to pivot parallel to the remaining Tembusu, thus facing the north–south direction. The remnants of the demolished tree were fashioned into a sculptural artefact by artist Tony Twigg, while sawn timber from the tree was recycled as vertical cladding.

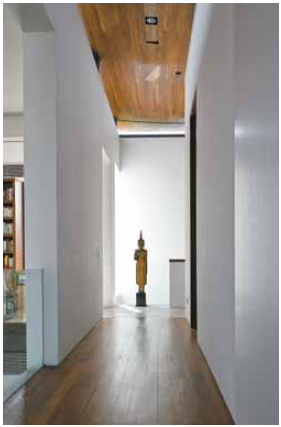

From a short driveway the house is entered via a dramatic staircase constructed from huge slabs of basalt stone from Fujian. At the head of the staircase, and immediately alongside the entrance door, is a giant Buddhist prayer wheel from Bhutan, commissioned by the owners. Recycled timber planks from a demolished house in Chiangmai are used for flooring, and circular columns from the same source are incorporated in a screen alongside the entrance. The grey stone ‘skin’ on the pavilion next to the entrance was painstakingly selected by the architect from a quarry in Xiamen. These materials and artefacts speak of the owners’ deep interest in Asian cultures, as does the music pavilion where the principal instrument is an Indonesian gamelan.

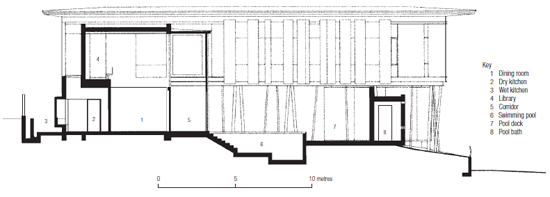

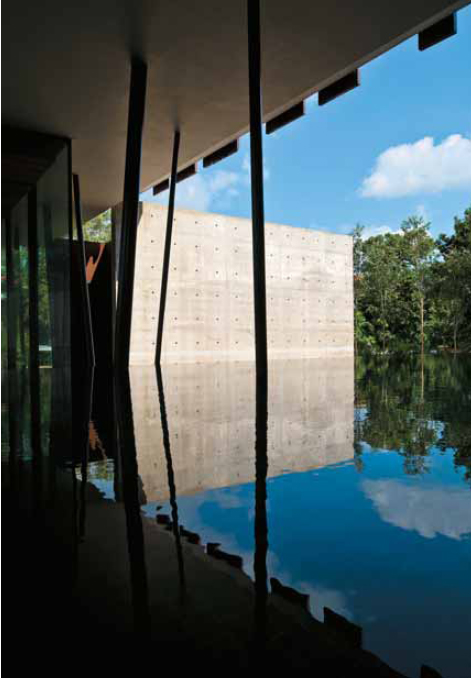

The plan of the two-storey house is ‘U’-shaped, embracing an infinity pool. The language employed is totally modern while incorporating traditional responses to the monsoon climate of Singapore. The living room, dining room and reception area open out to a broad terrace flanking the swimming pool. Yet, these spaces can also be enclosed and air conditioned, a necessary response to protect the extensive library of books arranged along an open gallery overlooking the main living space.

This is a house designed to suit the tropical climate–open and naturally ventilated during the cooler monsoon seasons or closed and air conditioned for the hot and humid period of the year. Its flexibility and blurred delineation means life takes place within the so-called ‘in-between’ space at the interface of the interior and exterior. With this underlying philosophy and the use of recycled components, the house is overwhelmingly sustainable–a key requirement of contemporary design.

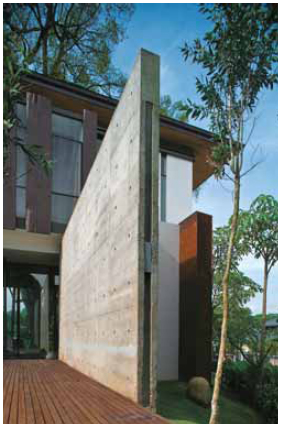

The sensitivity towards texture and colour of the landscape influenced the expressive choice of a wide range of materials. While the large, precisely crafted double-glazed windows enhance the notion of transparency, the surgically fitted surface-weathered cut stone makes a powerful yet sensual balance. The chunky proportioned timber cladding and sun-shade delicately weave in between, giving the surface more depth and shadow.

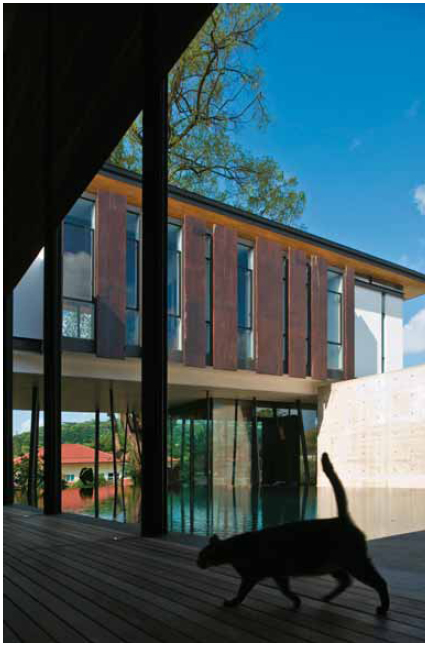

One other unusual feature that differentiates the design is the use of large sheets of Corten steel to clad the pool changing room/toilet facing the main road. The orange-red rusty metal is assembled with wabi-sabi imperfection and is remarkably attractive. The colour is very much in harmony with nature. Seemingly randomly located slender, circular steel columns support the bedroom wing, simulating, to some extent, a grove of bamboo and integrating benignly into the landscape.

A dramatic double-height living room overlooks the swimming pool terrace.

An extensive library occupies the gallery overlooking the dining and living area.

Alongside the gamelan room is an informal ‘performance space’, with a white-walled backcloth, that can be viewed across the infinity pool from the living room terrace. This space instantly summons up visions of wayang kulit, the shadow play performances of Indonesia.

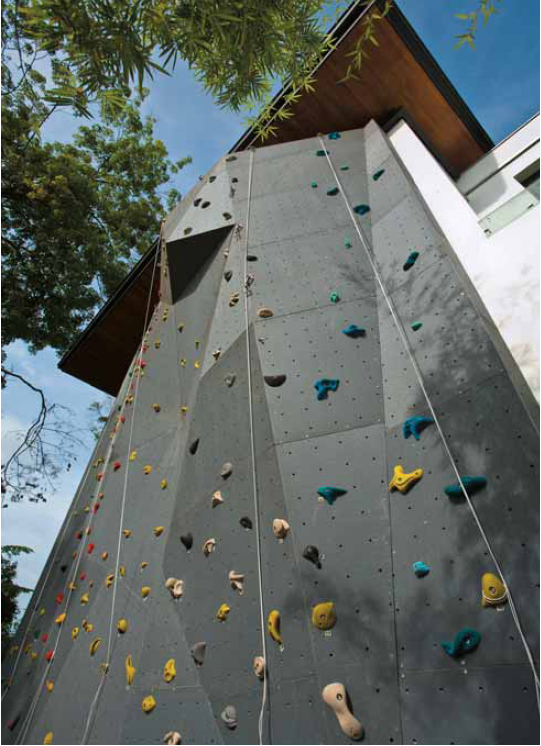

A unique feature, certainly for Singapore, is the incorporation, on the rear façade of the house, of a six-metre-high climbing wall. The house, says Ko Shiou Hee, was intended to have ‘an elusive edge. It is a collage of planes and volumes.’ Transition is defined with changes in floor level. The ground floor is a series of transparent, interconnected spaces that flow easily from interior to exterior. The more private spaces of the house are lifted to treetop level supported on planes and slender, circular, inclined columns that merge with the landscape. ‘The project,’ explains Ko, ‘explores the theme of visual and phenomenal transparency, through strategic spatial organization and abstraction of form and materials.’

The notion of phenomenology continues to be central to Ko Shiou Hee’s architecture. The Landscape House is a wonderful tactile design and there is a growing maturity in the architect’s work. In this instance, a capable assistant architect–Kee Jin Zhi–aided Ko. For the architectural critic, the house appears to be perfectly ‘tailored’ to the specific requirements of the owners, with the incorporation of multiple programmes.

Asian artefacts are displayed against white walls with sensitive natural lighting.

An off-form concrete wall forms a backcloth for informal performances.

A projecting window in the master bedroom frames a giant Tembusu tree.

Traditional implements from all over Asia adorn the walls of the dining room.

A giant prayer wheel from Bhutan flanks the entrance to the house.

Large slabs of grey stone from Xiamen are used to clad the pavilion alongside the entrance.

Corten steel is used to clad the pool changing room.

The swimming pool deck viewed from the undercroft of the bedroom wing

The section indicates the dining room and terrace overlooking the swimming pool.

The designer’s intention was that the house should ‘disappear’ into the landscape.

The white concrete wall of the pool changing room defines an outdoor performance space.

At the rear of the house is a six-metre-high climbing wall.

Huge slabs of basalt stone from Fujian feature in a dramatic entrance stair.

Two huge Tembusu trees form a backdrop to the house.

Footnote

1 Robert Powell, ‘Space, Light and Materiality’, SPACE, No. 1, Singapore: Panpac Media, March 2001, pp. 76–81..