As the boundary of the province advanced northward and westward to its present location, the relative isolation of earlier times ended. The building of railways and the subsequent advent of “bush” flying connected Northern Ontario with the outside world. In the wake of the train and aircraft came a whole host of newcomers whose arrival had a profound impact on the land and the Native people. (See Map 13.1b, page 290.)

Prior to 1890 the major representative of the outside world had been the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC). After 1890, however, the arrival of a new wave of fur traders, either independent or representing rival companies, introduced an era of competition. At about the same time, Christian missionaries came more frequently and stayed longer. North of the Albany River government officials, surveyors, prospectors, commercial fisherman, loggers, and miners soon joined them.

The canoe and toboggan were well adapted for their traditional functions, but neither they nor the fur traders’ York boats could carry the large quantities of goods required by the settlers and developers who became increasingly interested in exploiting the potential of a new frontier. With the building of railroads, however, old transportation routes and trade networks were quickly abandoned and contact with the outside world dramatically intensified.

Major changes followed the completion of the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) in the mid-1880s. Though the line ran mostly south of the height of land, it did cross the northern watershed at several locations, which led to the decline of some traditional supply routes. In the west the CPR station at Wabigoon (Dinorwic) became a major jumping-off point into the territory of the upper Albany for surveyors, scientists, and government officials. From 1890 onwards, supplies for the Hudson’s Bay Company post at Osnaburgh House were brought in from Wabigoon rather than by the traditional route up the Albany River from James Bay.1

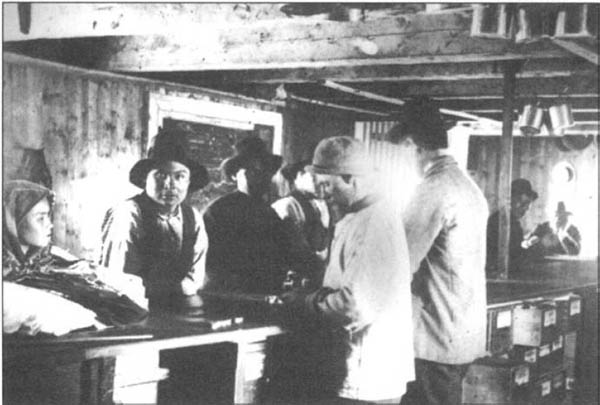

Interior of the Fort Albany post, around 1905.

Provincial Archives of Manitoba, Hudson’s Bay Company Archives, HBCA Photograph Collection, 1987/363-A-6.1/1 (N8287)

Further inroads occurred just prior to the First World War, when the eastern division of the National Transcontinental (later merged with the Grand Trunk Pacific – the western division of the National Transcontinental – and the Canadian Northern into the Canadian National Railways [CNR]) completed a line further to the north, running through Cochrane and Sioux Lookout. Except for a short stretch above Lake Nipigon, this line ran north of the height of land. Because it crossed the headwaters of several major rivers running north and east to James Bay, it had an even greater impact on established trade and supply routes in the Patricia District and the Hudson Bay Lowland than did the CPR.

By 1910 Moose Factory already had a communication link along the Abitibi River to the town of Cochrane. During the summer, the Hudson’s Bay Company shipped goods down-river by boat, and in winter, mail from the south was carried along the same route by toboggan.2 Another railway depot was located on the Moose River system at Mattice, where the company opened an establishment in 1920. This resulted in the closure of English River, one of the last of the traditional inland posts in the Moose-Missinaibi river valley.3

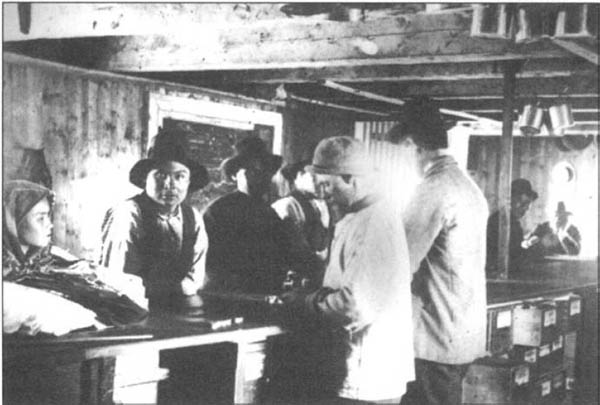

Interior of the Sales Shop, Hudson’s Bay Company store, Moose Factory, 1934. Paddy Houston is shown at the counter.

Provincial Archives of Manitoba, Hudson’s Bay Company Archives, HBCA Photograph Collection, 1987/363-M140/2 (N79–142)

During the First World War a water route opened from the railway at Pagwa, down the Pagwachuan to the Albany River. The Révillon Frères Trading Company (a subsidiary of Révillon Frères of Paris, which began operations in James Bay in 1904) began to use this route after they had trouble chartering a ship to take their supplies from Montreal to James Bay. It was found convenient and later adopted by the Hudson’s Bay Company as well.4

Another new north-south supply route commenced at Ombabika (Auden since 1948), farther to the west. This canoe route led, through a series of lakes and portages, to Eabamet Lake (Fort Hope) on the Albany River. From there, supplies were carried by a similar water route to the upper Attawapiscat and Winisk rivers. Supply brigades on this route used canoes that were about six metres long rather than the customary York boats, formerly employed on the Albany River. In another departure from tradition, the canoeists rowed rather than paddled, in commercially produced canvas-covered Peterborough, Lac Seul, and Rupert’s House canoes.5

The railways had less impact in the extreme north. There, traditional supply routes remained in operation during the early twentieth century. Fort Severn continued to operate as a major supply depot, shipping goods inland to Big Trout Lake and other locations in the upper Severn region. Further to the south, outposts in the Lake Winnipeg drainage area continued to obtain supplies via the Berens and Poplar rivers.

In 1930 the Ontario Northland Railway established a terminus at Moosonee,6 which brought the James Bay Cree into closer contact with the south. It now became possible to ship goods to James Bay by land throughout the entire year. From Moosonee, supplies could be forwarded farther north by sled in winter and boat in summer, and eventually by aircraft in all seasons. Tractor trains came to be another means of supplying northern settlements.

The advent of bush flying gave the aircraft an important role in northern transportation. In the 1920s a number of airlines began operation in Northern Ontario: Laurentide Air Service Limited, Northern Air Service Limited, Jack V. Elliott Air Service, Elliott’s Fairchild Air Service, Patricia Airways and Exploration Company Limited,7 and Western Canadian Airways.8 By the mid-1930s Canadian Airways made winter flights from Collins to such distant posts as Big Trout Lake and Bearskin Lake, previously considered among the most isolated posts of the fur trade.9 In these early years of aviation the Ontario government’s Provincial Air Service also came into being, primarily to operate in the north.10

The beginning of the twentieth century saw the final destruction of the fur trade monopoly that the Hudson’s Bay Company had enjoyed since 1821. Competition arrived, first from the south, from the many access points on the new railways. Individual freetraders needed little outlay to get started in the fur business. According to one observer, the first traders to come in with the railways brought with them “a keg of the strong alcohol, a few cheap gilt watches, some fancy ribbons, coloured shawls and imitation meerschaum pipes, and if they found their bundles would bear a little more weight, they generally put in a little more whisky.”11

In addition to the individual “whisky peddlers,” more respectable opponents emerged to oppose the Hudson’s Bay Company “in a straight way,” by trading to the Indians “good strong clothing and good provisions.”12 While a number of these small companies (often composed of no more than two to four people) went bankrupt after one or two years, some survived. Organized competition to the HBC became very strong in the early twentieth century.

The Révillon Frères Trading Company became the leading opponent. By 1910 this powerful organization had expanded to the point where it had posts at most of the places where the Hudson’s Bay Company traded. During the Depression of the 1930s, however, Révillon’s business declined rapidly. The HBC bought its opponent’s assets in Canada in 1936.13 Smaller organized competitors to the HBC in Northern Ontario included H.C. Hyer of Winnipeg, who moved into the upper Severn area from Island and God’s lakes around 1907; the G.A. MacLaren Trading Company, which operated in the Osnaburgh House area from 1901 until bought by the HBC in 1910;14 and, at a later period, Patricia Stores Limited which traded as far north as Windigo Lake,15 and the Savant Lake Trading Company.16

Competition became keenest towards the end of the First World War, when raw fur prices reached record highs on the world market. A comparison of sample fur prices for 1916 and 1918 indicates that beaver jumped from $5.96 to $14.84, ermine (per forty) from $20.68 to $41.37, marten from $7.06 to $17.76, and otter from $9.61 to $14.84.17 According to J.W. Anderson, a veteran fur trader, as a result “every Tom, Dick and Harry rushed into the fur trade.”18 The new traders, based at points on the railway, needed only a toboggan, a few dogs, camp equipment, and a roll of dollar bills. (As this observation suggests, cash had become more common in exchange transactions between fur traders and Indians.)

The competition led to an increase in the number of available trade outlets as the larger fur trade companies also operated, in addition to their regular trading posts, smaller outposts. These “camp trades” (small trading outposts such as Big Beaver House, Wunnummin, and Sandy Lake) stocked only basic essentials, such as flour, sugar, tea, and ammunition, and simply exchanged furs for goods without using either cash or credit. Indian or mixed-blood company employees ran many of the camp trades in Northern Ontario.

The rise of competition led to the reintroduction of alcohol, formerly forbidden by the Hudson’s Bay Company after its amalgamation with the North West Company. In areas exploited by the whisky pedlars, alcohol had a demoralizing effect on local Indian populations.

Before 1890 Christian missionaries had restricted their outreach to southern regions, such as the Boundary Waters and Abitibi areas, and to the coast of James Bay. A new approach began in the 1890s with a rapid expansion into the northern interior and up the coast of Hudson Bay. Of the three denominations competing for converts – Anglicans, Methodists, and Roman Catholics – the Anglicans had the greatest impact in the northern interior.

Native clergy led the Anglicans’ missionary campaign. Bishop Horden at Moosonee instructed and ordained Edward Richards, a James Bay Cree, and William Dick, a Cree catechist from York Factory. Others were trained in the south, such as Richard Faries, a Cree mixed-blood who was born and brought up at Moose Factory and who spent two years at Montreal Theological College before his ordination in 1898. These men staffed the new mission stations located at strategic inland locations. As mentioned in the previous chapter, William Dick managed the mission at Big Trout from the 1880s until his retirement in 1918. During his ministry he established a mission station at Fort Severn and travelled widely throughout the upper Severn and upper Winisk regions, making converts, baptizing, and marrying.19 He also trained Native catechists.20 The Anglicans established another important inland mission at Fort Hope on the upper Albany, where the Hudson’s Bay Company had built a post in 1890. Richard Faries directed the mission station until 1899, when it was taken over by Edward Richards. Native catechists ran outposts from the Fort Hope Mission at two other locations on the Albany River: Osnaburgh House and Marten Falls. In addition, Anglican workers made seasonal trips north to the upper Attawapiskat River and as far as the boundaries of William Dick’s missionary field on the upper Winisk.

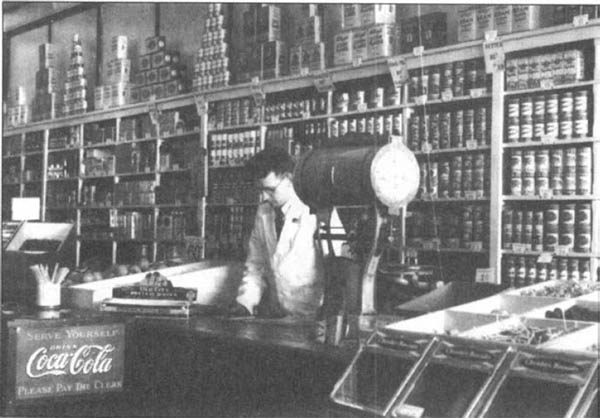

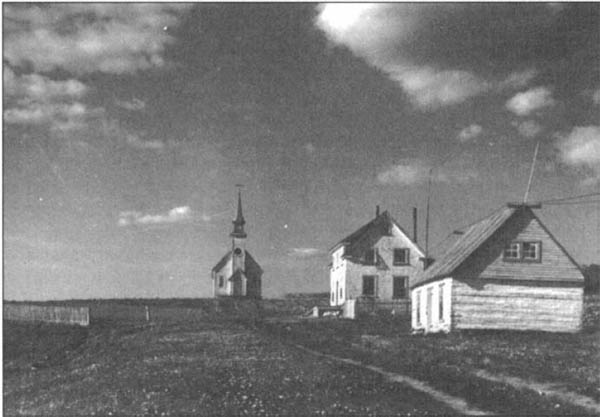

Long Lake, Ontario, 1906. Note the Hudson’s Bay Company post and the neighbouring church with the Indian lodges in front of it.

National Archives of Canada, PA-59579

Roman Catholic missionaries also ventured northward during the 1890s, concentrating particularly on the Cree of James and Hudson bays. In 1892 the Oblates, who had formerly made visits to James Bay from Abitibi, established a permanent mission at Fort Albany. From this vantage point, northwest of the old Anglican headquarters at Moosonee, they made summer visits up the coast as far as Winisk, and up the Albany River as far as Fort Hope.21 Later, the Oblates built permanent missions at Attawapiskat (1912) and Winisk (1934).

The Methodists worked in northwestern Ontario, operating from their older mission posts in Manitoba. One of the early Methodists in Northern Ontario was Reverend F.G. Stevens, who made annual visits to Sandy Lake from 1899 to 1907.22 After church union in 1925, the United Church of Canada continued many of the former Methodist missions.

The missionaries soon became involved in education and health. In 1902, for example, the Grey Sisters of Ottawa established both a boarding school and a hospital at Fort Albany. The children were brought to the boarding school from coastal Cree communities and from Ojibwa families as far inland as Fort Hope. The Anglican missionary established a day school at Fort Hope in 1910. In 1945 Oblate missionaries started sending Ojibwa children from the upper Albany region to a boarding school at McIntosh, Ontario, on the Canadian National Railway line west of Sioux Lookout.23

“Roman Catholic, Anglican, and Methodist missionaries began to impact upon the spiritual life of northern Algonquians about the middle of the nineteenth century, and ultimately Christianity became the dominant religion. Even on the trail, most of the people I travelled with observed morning and evening devotions. Still, elements of older beliefs survived in places, including Sandy Lake, the site of this Roman Catholic mission” – John Macfie (who took this photo in 1955)

From John Macfie and Basil Johnston, Hudson Bay Watershed (Toronto: Dundum Press 1991), 71

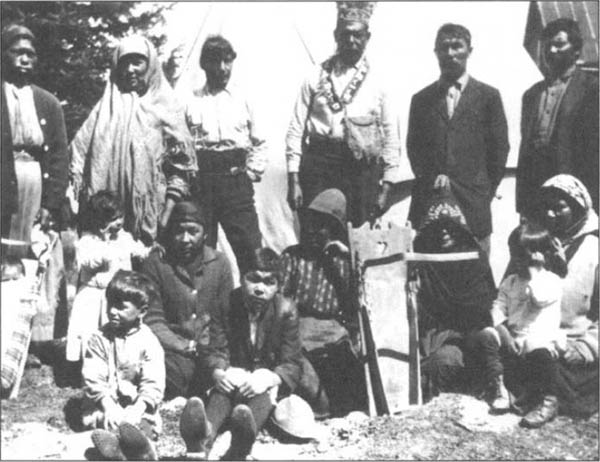

Father Joseph-Arthur Bilodeau (1886–1963), an Oblate missionary and director of the Roman Catholic Indian school at Fort Albany (1925–38), photographed with Cree in the James Bay area, 1933. Father Bilodeau served for nearly half a century in the Roman Catholic missions on the west coast of James Bay (1919–63).

Archives Deschâtelets, Ottawa

Government surveyors and map makers became more active in Northern Ontario at the turn of the century.24 The extension of Ontario’s northern boundary from the Albany River to Hudson Bay, completed in 1912, placed these lands under provincial jurisdiction (the area south of the Albany River and north of the Great Lakes drainage basin had been transferred to Ontario by 1889).25

In the early twentieth century the federal government made treaties with the Amerindians in the area of what is now Northern Ontario. The first treaty with the Indians of the Hudson-James Bay drainage area was Treaty No. 9, signed in 1905 and 1906.26 It covered all unceded territory from the height of land to the Albany River, which remained the northern boundary of Ontario until 1912. Treaty No. 9 was followed by an extension of Treaty No. 5 by which the Indians ceded the territory around Sandy Lake (1909) and Deer Lake (1910). Finally, the Treaty No. 9 adhesion (1929 and 1930) included all the remaining territory north of the Albany River (see the Map 14.2).

Once the Native people had signed treaties, the federal government set aside land for reserves, each reserve to contain 2.6 square kilometres (one square mile) for every family of five people. Often years passed before the government surveyed the boundaries. Annually, officials of the Indian Affairs Branch, who were usually accompanied by a doctor and an officer of the North-West Mounted Police (later Royal Canadian Mounted Police) visited the various bands. During the summer of 1924, the annual treaty party for the Treaty No. 9 area made its usual trip down the Albany River, departing from Dinorwic and stopping at Osnaburgh House, Fort Hope, Marten Falls, and Fort Albany, but it then used a sea-plane to reach the remaining bands. After this date, the treaty party increasingly travelled by plane.27

The annual arrival of the treaty party became an event of major significance to the Indians. The occasion began with a volley of gunfire to greet the canoes bearing the government officials. The status Indians received their annuity payments, which usually amounted to four or five dollars per person, depending on the terms of the treaty. The officials distributed gifts of clothing, blankets, and fish nets, as well as rations for the sick and disabled. The treaty party also contributed to a feast that usually accompanied the celebrations. Occasionally the party met with hostility, as in 1907 at Lake of the Woods when Indians threatened the agent.28

Although a police officer accompanied the annual treaty party, law enforcement did not pose a serious problem. One of the few exceptions occurred in 1907, when two North-West Mounted Police officers arrested the conjurer Pesequan (alias Joseph Fiddler) and Jack Fiddler at Sandy Lake and brought them out to trial at Norway House.29 Pesequan had been involved in the ritual murder of a woman who had been delirious for several days and who had thus, according to traditional belief, constituted a threat to the community. Fiddler’s death sentence was later changed to life imprisonment, but he soon died in confinement. Infrequently, the police also had to transport Indians who had gone insane to the outside for treatment.30

Signing of Treaty No. 9 at Windigo, Ontario, 18 July 1930. Standing: Samuel Sa-wanis, John Wesley, Dr. O’Gorman, Chief Ka-ke-pe-ness, and Senia Sak-che-ka-pow.

National Archives of Canada, C-68920

Although a doctor sometimes travelled with the treaty party, the Indians remained isolated from professional medical attention and facilities. Each trading post normally kept first-aid equipment and a limited supply of medicines. The traders and missionaries might dispense these. Rations for the sick and destitute were also distributed in this manner, and in a few instances aircraft were used to fly emergency cases to hospitals in the south. In spite of occasional epidemics and the obvious limitations of the medical system, there might have been some districts where population increased during the early twentieth century.31 In other areas, population fluctuated but did not begin to rise until after the Second World War. This was the case for those Indians residing in the upper Severn River drainage basin. Fluctuating numbers of country game may have accounted for this. A severe shortage of country food existed, for example, in 190032 and during the winter of 1908–1909.33

Changes in the material culture of the Indians were easily observable and frequently noted by outsiders. After 1890, for example, traditional shelters gave way to new types of dwellings, one being the moss-covered conical lodge, similar in basic structure to its bark- or hide-covered predecessor, but covered with a thick layer of moss for greater winter warmth (see chapter 13).34 This semi-permanent structure had to be built in the fall, before the earth froze solid, and was therefore better suited for the more sedentary lifestyle that emerged during this period.

More-permanent structures, styled after those of the settlers, had become common by 1900 in the Boundary Waters area. By the First World War the Indians adopted log cabins in the north as well, at widespread locations such as Pikangikum,35 Windigo Lake,36 and the upper Winisk River.37 Although originally built only by “prominent” individuals, log cabins became the normal winter dwelling by the 1930s. The Indians used both round and squared logs, and commonly made roofs of either the ridge or hip variety. The earliest cabins were heated with open fireplaces of mud,38 but wood stoves soon became a standard feature.

Some people continued to use conical and dome-shaped lodges as summer dwellings, with canvas supplementing or replacing bark and hides for the covering. Canvas wall tents gradually became more common during the early decades of the twentieth century. Though the wall tent eventually replaced the traditional lodges, it was sometimes attached to such dwellings as an additional room or rooms. The customary open fire heated the lodge, while the occupants used any adjoining tent or tents as sleeping quarters.39 Such a composite dwelling could house several families and thus probably replaced the traditional multi-family ridge-pole lodge. On the trapline the Indians put up wall tents as winter shelters, which they heated with a light wood stove made from sheet metal.

An Ojibwa camp near the Ogoki River, north of Lake Nipigon, 1923.

Photo by Joseph Green, Archives of Ontario, Acc. 9348 s15105

Native family by their log cabin, located near Hardrock, which is near Geraldton, northwestern Ontario.

Photo by E.C. Everett, Thunder Bay Historical Society, 974.2.72

A Cree settlement near Moose Factory, January 1946. The Cree lived in tents with walls roughly one metre in height. The walls were made of logs chinked with moss and mud.

Photo by Bud Glunz, National Archives of Canada, PA-189737

Winter transportation became more efficient around 1900 with the adoption of dogs for pulling sleds.40 A good dog team could average about fifty kilometres per day in winter, a distance that could be increased to about eighty kilometres during the lengthened daylight hours of spring.41 At about the same time as the Northern Algonquians adopted dog teams they began to use two new types of sled. One of these was modelled after the Inuit dogsled and was probably introduced by missionaries and traders familiar with the Arctic. The other, sometimes referred to as a “prospector’s sled,” was built up on a pair of runners shaped like skis. It travelled more effectively on soft snow than the Inuit sled and kept a load higher and dryer than the traditional toboggan.

Noticeable changes also occurred in summer transportation. Canvas-covered canoes began to replace those made of birchbark shortly after the turn of the century. Unlike the locally made bark canoes, most of the canvas canoes sold by the fur traders came from factories in Peterborough or from Lac Seul and Rupert’s House. Native people hired by traders to deliver them to posts as far north as Big Trout Lake usually picked up the empty canoes at the nearest railhead. Each canoe was delivered by a solitary man, who used oars and home-made oarlocks rather than the more traditional paddle. By the 1930s, outboard motors had become a common sight on freighter canoes and were popular with those who could afford them.

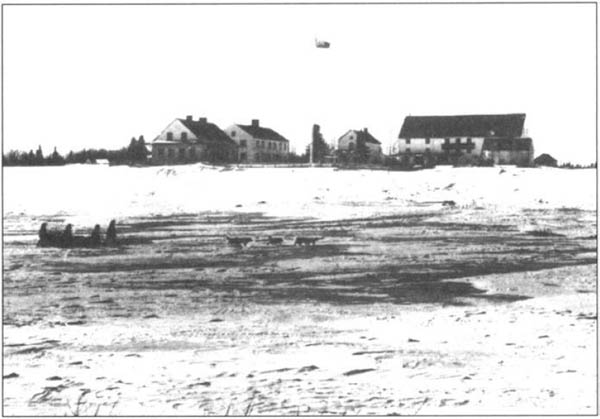

A dog team returning to Moose Factory, 1934.

Photo by H. Bassett, Provincial Archives of Manitoba, Hudson’s Bay Company Archives, HBCA Photograph Collection, 1987/363-M-110/55 (N79–135)

By the early twentieth century the Northern Algonquians had discarded most of their former clothing, except for occasional rabbit-skin costumes.42 Nevertheless, many Native people continued to wear hide moccasins and mittens, frequently decorated with silk embroidery or, more often, glass beads. The more traditional use of coloured porcupine quills had become rare by the turn of the century, although it apparently persisted in the Red Lake area as late as 1915.43 Those living nearest southern non-Native settlements occasionally donned ceremonial costumes (usually reflecting heavy Plains Indian influence) to celebrate powwows or to entertain tourists.

A useful innovation from Northern Quebec was the sealskin boot, which provided waterproof footwear during the warmer seasons. The Hudson’s Bay Company distributed the Inuit-made product to Northern Ontario locations, such as Fort Albany and Attawapiskat.44 Eventually, the Cree living on the coast of Hudson and James bays started making their own sealskin boots, including one type that had a regular moccasin foot with a sealskin upper.

In the Boundary Waters area, many Ojibwa at the turn of the century started to supplement fishing, hunting, and trapping with farming and seasonal wage labour. Indians in the vicinity of Lake of the Woods planted potatoes, pumpkins, carrots, and turnips, all of which they stored underground for the winter.45 They dried corn and stored it in birchbark storage houses, along with large quantities of maple sugar, berries, fish powder, and dried moose and muskrat meat. Hay was cut, dried, and stored for cows, kept for both meat and milk, as well as for horses.

In the Kenora region, dam construction, which began in the late 1880s, caused widespread flooding. This reduced wild rice yields and also fish and muskrat harvests. Similar results occurred in Lake St. Joseph when an Ontario Hydro dam raised the water level three metres.46

North of the Albany River small gardens became common by the turn of the century in such remote localities as Lake St. Joseph, Lake Attawapiskat, and the area of Weagamow Lake.47 The Native people stored potatoes, the main crop in these northern areas, in pits dug in hillsides or under the floors of log cabins. At first only a few individuals grew potatoes, but by the 1930s many did. Imported food became more readily available in the 1940s, and after this, gardening declined rapidly.

Treaty No. 9 Commissioner Samuel Stewart describes Chief Louis Espagnol (Espaniel), an Ojibwa chief from the Spanish River, as he appeared at the treaty discussions at Biscotasing, 12 July 1906: “Louis was attired in great splendour and his appearance was greatly admired. He had on a Caribou skin uniform with any amount of fringe, as well as pendants of goose bones with tips of deer skin. The Jacket had pockets of red and blue cloth, decorated with beads of various colors. He also wore garters similarly decorated. On his feet were a pair of Caribou moccasins with porcupine designs. He wore a wampum bandolier, and on his breast were two large George 3rd silver medals . . . Taking him all in all, Louis was quite a heavy swell, and he was very well aware of the fact.”

National Archives of Canada, PA-59558

In some areas large game animals increased in numbers towards the end of the last century. This provided a welcome addition to the fish-hare diet that had become so common earlier in the century. Caribou, for instance, became more numerous in the Trout Lake area in the 1870s48 and in the upper Albany area in the 1880s.49 After having been almost exterminated in the early nineteenth century, moose re-entered Northern Ontario around 1900. The return of these important large game animals made famine less of a threat, and it also provided hides for moccasins, mittens, and snowshoe webbing, all of which had had to be purchased from the traders when locally unavailable.

Fish continued to be a major foodstuff, and fishing provided some Native people with a chance to earn wages from the traders. The development of large-scale commercial fishing for export, however, awaited air transportation in the north. One of the first fish products to be exported by aircraft was fresh caviar, obtained from Indians who fished sturgeon along the Albany River and as far north as Muskrat Dam Lake on the Severn River. To keep the caviar fresh, the Indians first netted the sturgeon and then tethered them to stakes in the water to keep them alive until the sound of an approaching aircraft could be heard. The fishermen quickly hauled out the fish and removed the caviar for immediate shipment to southern markets.50 This practice, however, soon depleted sturgeon throughout Northern Ontario.

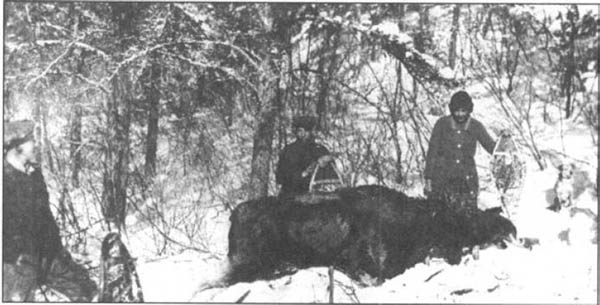

The Beaucage family with a moose taken near Biscotasing in the 1920s.

Archives of Ontario, Acc. 10144

Drying moose meat, Lac Seul, 1919.

Photo by F.W. Waugh, Canadian Museum of Civilization, 45686

A woman scraping a moose hide for tanning, Lac Seul, 1919.

Photo by F.W. Waugh, Canadian Museum of Civilization, 45773

Opportunities for wage labour became more varied. Seasonal employment as tourist guides continued, but now some Indians found jobs with the railways, lumber camps, and mills. After the decline of fur prices in the 1930s, some Native trappers also worked in mines, moving with their families to such places as Red Lake, Pickle Lake, and Favourable Lake. Many, however, found the adjustment from their old lifestyle and the prejudice of non-Native coworkers too great, and returned to the bush after a relatively short time.

As employment opportunities increased in the south, they gradually diminished for the Cree at Moose Factory and Fort Albany. With the arrival of the railways, these posts lost much of their former importance as supply depots. Farther north, however, the fur traders still required individuals to staff the boats from Fort Severn to Big Trout Lake into the 1940s. At times they hired as many as sixty or more men each summer.51 After the adhesion to Treaty No. 9 was signed in 1929, many were reluctant to go on the brigades until after government officials had arrived. The Hudson’s Bay Company voiced its concern, claiming the timing of treaty payments interfered with its employment of the Indians.52

Most of the Northern Algonquians in Ontario remained dependent on trapping. By 1890 the trade goods regarded as “indispensable” included powder, shot, guns, axes, and nets, and many Indians had also become reliant on flour, pork, tallow, and wool clothing and blankets.53 During the early twentieth century the inventory of desired trade goods increased to include manufactured canoes, canvas tents, and even, for some, violins and gramophones.

Two photos of the Cree village of Fort Severn on Hudson Bay, where the HBC first traded for furs over 300 years ago. The upper photo was taken in the summer of 1955; the lower in August 1964.

Photos by John Macfie, from John Macfie and Basil Johnston, Hudson Bay Watershed (Toronto: Dundum Press 1991), 27

As the desire for trade goods grew, so did the pressure on fur resources, particularly in areas near the railroad, where freetraders encouraged the Indians to violate conservation methods. In these “frontier” locations, Native trappers found a ready market for out-of-season skins and sometimes they continued to trap for ten months of the year.54 At interior posts the HBC enforced conservation by restricting fur trapping to the period from 25 October to 25 May, although freetraders sometimes encouraged the Indians to do otherwise.55 The intense pressure on fur resources came from Native and also from non-Native trappers, who spread across Northern Ontario in ever-increasing numbers in the early twentieth century. By 1890 non-Native trappers already encroached on Indian lands near Lake Nipigon and Sturgeon Lake, and by the turn of the century they had reached the vicinity of Osnaburgh House.56 The high prices for furs after the First World War brought an influx of non-Native trappers to areas as remote as Sandy Lake.57

As the veteran fur trader J.W. Anderson pointed out, the non-Native trappers had a higher standard of living and were much harder on fur resources than the Indians.58 An Indian in the 1920s, living largely off the land, could get by on an annual trapping income of approximately $300 to $400. As Anderson mentions, however, his non-Native counterpart required a winter outfit of food and equipment amounting to at least $1 000. The search for a greater number of furs contributed to the sharp decline in the number of fur-bearing animals by 1929. Once this happened, non-Native trappers began leaving the region.

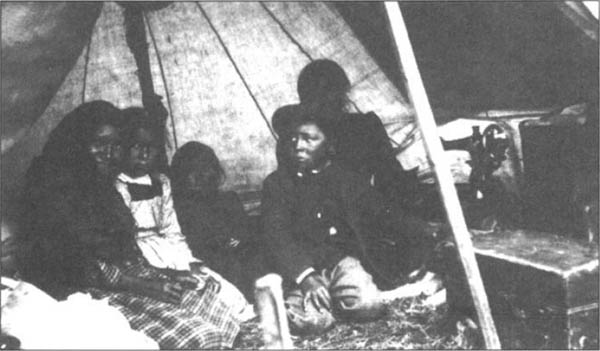

These treaty Indians in Abitibi owned a sewing machine (shown on the right), June 1906.

National Archives of Canada, PA-59520

Joe Espaniel, a great-nephew of Chief Louis Espaniel (see page 357), c. 1915. Joe Espaniel came from Pogamising near Benny, on the CPR line between Sudbury and Chapleau. He enlisted in the Canadian Expeditionary Force and was killed overseas. A number of other Northern Algonquians also served in the Canadian Army in the First World War.

Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Jim Espaniel Collection

Especially hard hit by overtrapping was the beaver. By 1890 the Hudson’s Bay Company trader at Osnaburgh House had already expressed fears that beaver had declined and might be exterminated. He attributed this to the fact that the Native people, constantly driven back by the encroachment of hunters from elsewhere, no longer spared a few animals for breeding, “as has hitherto been their custom.”59 The intensive trapping that resulted from boom prices in the 1920s also contributed to the depletion. By 1935 J.W. Anderson reported that the younger Attawapiskat Indians had actually never seen a beaver.60

Traditional forms of social organization changed considerably during the early twentieth century. Probably the “line” Indians (those who moved their primary place of residence from the bush to scattered settlements along the railways) experienced the most profound change. Life in the railway communities, in close proximity to a predominantly male population of non-Native transients, generally had a disruptive effect on old patterns of family and community life. A study completed at Collins, Ontario, indicates that the families relocated to such an environment often experienced a general feeling of apathy and aimlessness. Marriage breakdowns also increased.61

Among the bush Indians the effects of contact may have been less disruptive, but even away from the railways their social organization was altered in a number of ways. At the family level, polygyny declined around the turn of the century, after Christian missionaries and government officials explained federal laws against plural marriage.62 Another change that resulted from external pressure was the adoption of family surnames.63

As a rule, missionaries now formalized marriages but parents continued to play an important role in the choice of marriage partner for their children. Marrying outside of one’s clan (clan exogamy), once important in the regulation of marriage in the Boundary Waters region, had already started to lose its former importance along the upper Albany river by 1910.64

In the area of the upper Winisk and Attawapiskat rivers, the semi-sedentary “all-Native settlement,” where people lived in log cabins for ten or more months of the year,65 gradually replaced the nomadic hunting group. Women and children usually remained in these settlements when the men went to their traplines during the winter months. During the summer those families who visited the trading post at treaty time lived near the posts in cloth tents.

“The Family Circle,” Kagianagami Lake, Ontario, c. 1941. Kagianagami Lake is on a tributary of the Albany River just south of Fort Hope, located between the Albany and Ogoki rivers.

Provincial Archives of Manitoba, Hudson’s Bay Company Archives, HBCA Photograph Collection, 1987/363–1-82/18 (N9314)

These semi-sedentary all-Native settlements became larger than the earlier hunting groups. The six all-Native settlements existing in the Lansdowne House area during the 1940s, for instance, ranged in size from 42 to 100, with an average population of 62.66 At such settlements, kinship affiliations continued to be an important factor in determining the composition of the residential group. Primary kin ties connected the vast majority of married couples with other community members.

As the settlements increased in size, a tendency grew to choose marriage partners from within the same community (endogamy). In 65 percent of all marriages in six all-Native settlements, both spouses had resided in the same community prior to marriage.67 This remarkable incidence of community endogamy is another way in which the all-Native settlements differed from the older hunting groups, which had been largely exogamous units.

Little detailed information on the social organization of the Indians prior to the 1950s exists, making it difficult to plot the distribution of the semi-sedentary all-Native settlements. They appear to have been slow to develop in isolated areas such as Weagamow Lake.68 At another isolated location, Pikangikum, Ojibwa co-residential groups (all-Native settlements) remained small, with an average of only twenty-three persons as late as 1939.69 Furthermore, at Pikangikum log cabins remained uncommon, with only an average of 1.5 houses per settlement. Many people must still have spent the winter in tents or traditional lodges.

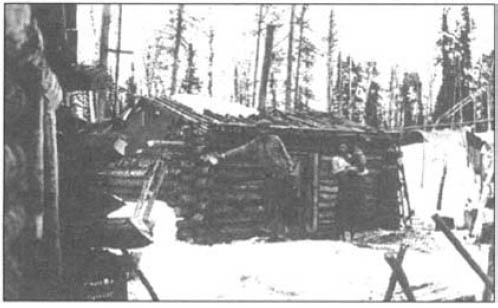

Interior of Charlie Moore’s trapping cabin, Bear Island, Lake Temagami.

Archives of Ontario, Acc. 9164 s15164

Leadership within the all-Native settlements was probably based on several criteria, some traditional and some modern. Although the male head of the largest extended family no doubt remained an important figure, two new roles of great importance emerged: that of camp trader (usually a Native person) and, in the case of Anglican settlements, that of Native catechist. These functionaries sometimes exerted considerable influence over the lives of other people in their settlements. In some cases, people who were already leaders in the more traditional sense filled these roles, thereby giving themselves an even greater authority.

Several factors made the development of semi-sedentary all-Native settlements possible. One was undoubtedly the availability of new and/or increased food supplies, both from store purchases and from local gardening. The use of dogs for sledding also made it easier to transport country food to the settlement, eliminating the necessity of constantly relocating to a new hunting ground.

After the treaties, many of the former trading post bands simply became treaty bands, adopted as convenient administrative units by the agents of Indian Affairs. Under the supervision of government officials, the treaty band elected a chief, who was expected to make a speech to the entire band at each annual feast. Elected councillors, the number of which was determined by band size, assisted the chief. Both chiefs and councillors received an honorarium ($25 per annum for a chief and $15 for councillors), suits, and medals. Appearances aside, the band had a loosely knit structure, and neither the chief nor his councillors had effective control over band members or revenues; nor did they have real authority over most of those widespread settlements they officially represented. The position of chief created by the government was, however, not a new development. In earlier times, the Hudson’s Bay Company had appointed chiefs for various groups of Indians70 (see chapters 12, 13, and 14).

Group of Lake Temagami Ojibwa on Treaty Payment Day, summer of 1913. Chief François White Bear appears in the centre, and the assistant chief Aleck Paul is shown standing to the right, next to Chief White Bear.

Canadian Museum of Civilization, 23991

Treaty No. 9 Indians shown gathering for treaty payments in front of the HBC post, Lansdowne House, Ontario, 1942.

Glenbow Archives, Calgary, NA-3235–68

Voting for the chief at Big Trout Lake, northwestern Ontario, 1947.

Photo by Jake Sieger, Provincial Archives of Manitoba, Hudson’s Bay Company Archives, HBCA Photograph Collection, 1987/363–I-83/79 (N9313)

After 1890 Christian beliefs and practices spread, as both Native and non-Native missionaries proselytized throughout Northern Ontario. In northeastern Ontario (where Anglicans and Roman Catholics competed for followers), the majority of the Northern Ojibwa appeared in official records as Christian converts by the 1910s. In northwestern Ontario, Pikangikum, one of the last areas to come under missionary influence, remained non-Christian into the 1930s.71

Particularly in those areas under the influence of Native missionaries and catechists, Christianity had a powerful impact. Some Indians around the Bearskin community, for example, experienced a great religious fervour during the winter of 1913–14. Two Indians had a vision in which they travelled to limbo, or the border of Hell, where they saw a lake of fire in which a swarm of souls struggled.72 After 1920 other Native leaders in the upper Attawapiskat and Winisk areas, inspired by biblical references to walled villages,73 had palisades built around their all-Native settlements.

In Ojibwa all-Native settlements, located far from mission stations, people gathered in the log homes of the resident Native catechist for daily prayer services. On the trapline they usually took prayer and hymn books in their own language, written in the special syllabics devised by earlier missionaries.74 In the 1930s Native catechists built churches in many Northern Ojibwa communities, such as Lansdowne House, Webique, and Nikip.

Most Indians in Northern Ontario, including those who formally accepted Christianity, retained some aspects of their traditional belief system. The concept of “power” remained a dominant theme in Native religious thought, even though new sources of power could be found in baptism and other Christian practices. Shamans continued in the twentieth century to perform traditional ceremonies, such as the Shaking Tent rite, and Native herbalists were called upon to cure illness and prescribe love medicines.75 In many Ojibwa settlements witchcraft continued as a cause of great anxiety, and most cases of illness, accident, and death were attributed to the sorcery of others.76

The Midewiwin society still functioned despite government and missionary attempts at suppression.77 The Midewiwin appears, however, to have declined in the early part of the century in areas distant from its greatest strength in the Boundary Waters area. It had already disappeared along the Albany River by 1909,78 while at Pikangikum it persisted until the last of the Midewiwin leaders moved to Lac Seul about 1920.79 Long after the Midewiwin was abandoned at Pikangikum, the dog feast, which once formed part of the Midewiwin ceremonies, was retained as an independent ritual.80

Another religious ceremony held in the Boundary Waters area was the Drum Dance. Apparently it originated on the Plains as a nativistic reaction to European contact and spread to the Ojibwa of northwestern Ontario during the late nineteenth century.81 The Indians made the sacred drums used during the ceremony from wooden washtubs; the tubs were covered with hide and suspended off the ground on four stakes. During the ceremony several men sat around the drum, beating and singing, while others danced. In time the social aspects of the drum ceremony became increasingly important, and it was enacted at powwows along the Winnipeg and Rainy rivers.

As Northern Ontario came into ever-increasing contact with the outside world after 1890, the Northern Algonquians experienced more and more alterations in their way of life. Among the most noticeable changes were new housing styles, with canvas tents, moss-covered lodges, and log cabins replacing the more traditional dwellings. Winter transportation became more efficient with the widespread acceptance of dogs and the adoption of two foreign types of sled. Another manifestation of change was the rapid decline of the traditional bark canoe, replaced by factory-made canvas canoes that were often propelled by outboard motors.

The subsistence economy of the Indians benefited by the return of moose and caribou to parts of Northern Ontario from which they had earlier disappeared. In the south, Native people supplemented wild food with small-scale farming, which included the raising of horses and cows. Even in the north, with its limited agricultural potential, gardening became fairly widespread, and people raised potatoes, storing them for winter consumption. These improvements in the food situation were partially offset by a decline in the yield of some traditional foods, particularly fish and wild rice, owing to resource development and commercial exploitation.

Trapping remained an important source of cash income but was adversely affected by a decline in the availability of fur, largely the result of overtrapping, abandonment of older conservation practices, and the encroachment of non-Native trappers during periods of high prices. Wage labour partially compensated the consequent loss of trapping income, necessary to purchase an expanding inventory of trade goods and store food. In the south, some took advantage of opportunities for work as tourist guides, commercial fishermen, miners, railway workers, and lumbermen. In the north, freighting remained a source of income into the 1930s.

The emergence of semi-sedentary all-Native settlements in some areas can be related to some of the technological and economic factors already noted. Especially noteworthy were the adoption of log cabins and the use of sled dogs, and the availability of new food supplies. In the Native communities, Christian missionaries and government officials worked to reduce the incidence of polygyny, while at the same time they introduced formalized marriages and the use of family surnames.

Finally, the rapid spread of Christianity characterized this period. Missionaries of various denominations, aided in many cases by Native catechists, succeeded in establishing missions and churches throughout most of Northern Ontario. As a result, almost all of the Cree and Ojibwa were nominal Christians by the 1930s. Nevertheless, many of the traditional religious beliefs and practices persisted side by side with the new teachings and survived into the period after the Second World War.

NOTES

1 Charles A. Bishop, The Northern Ojibwa and the Fur Trade, An Historical and Ecological Study (Toronto 1974), 79

2 J.W. Anderson, Fur Trader’s Story (Toronto 1961), 18

3 Douglas Baldwin, The Fur Trade in the Moose-Missinaibi River Valley, 1770–1917 (Ontario Ministry of Culture and Recreation, Historical Planning and Research Branch, Research Report 8, n.d.), 88

4 Anderson, Fur Trader’s Story, 150

5 See Hudson’s Bay Company Archives (HBCA), B.220/a/047, fo. 77; B.220/a/049, fos. 11, 13; B.220/a/050, fo. 8

6 S.A. Pain, The Way North, Men, Mines and Minerals (Toronto 1964); Albert Tucker, Steam into Wilderness (Toronto 1978)

7 L. Seale Holmes, Holmes’ Specialized Philatelic Catalogue of Canada and British North America (Toronto 1968), 211–26; C.A. Longwort-Dames, The Semi-Official Air Stamps of Canada 1924–1934 (Devon 1982), 11–52

8 National Archives of Canada (NA), RG 10, vol. 6889, file 486/28–3, pt. 8

9 The Beaver, outfit 265 (March 1935), 63

10 Bruce West, The Firebirds (Toronto 1974)

11 Martin Hunter, Canadian Wilds (Columbus 1935), 18–19

12 Ibid., 22

13 Anderson, Fur Trader’s Story, 195

14 Bishop, The Northern Ojibwa; HBCA, B.155/a/097, letter 22 May 1910

15 NA, RG 10, vol. 6819, file 490/2–17, Edwards to Scott, 7 September 1928

16 NA, RG 10, vol. 6889, file 486/28–3, vol. 8, Edwards to Awrey, 9 May 1929

17 Bishop, The Northern Ojibwa, 83

18 Anderson, Fur Trader’s Story, 138

19 Anglican Church Records (ACR), Register of Baptisms and Marriages, Trout Lake Mission 1855–1953, 2 vols. (Kenora)

20 E.S. Rogers, personal communication

21 Henri Belleau, “Les Missions de la Baie James,” L’Apostolat 11 (1940): 51

22 F.G. Stevens, “The Crane and Sucker Indians in Far North-Western Ontario,” Missionary Bulletin 15, no. 1 (1919): 121–6; A.D. (Mrs. F.C.) Stephenson, One Hundred Years of Canadian Methodist Missions (Toronto 1925), 123–7; George Lerchs, “The Sandy Lake Cree/Ojibwa,” Canadian Ethnology Service MS (Ottawa 1976), 24

23 Soeur Paul-Emile, Amiskwaski, la Terre du Castor (Ottawa 1952), 165

24 Morris Zaslow, Reading the Rocks, the Story of the Geological Survey of Canada 1842–1972 (Toronto 1975), 228

25 The question of Ontario’s boundaries is best reviewed in Norman L. Nicholson, The Boundaries of the Canadian Confederation (Toronto 1979).

26 J.L. Morris, Indians of Ontario (Toronto 1943), 46

27 NA, RG 10, vol. 6888, file 486/28–3, pt. 6

28 NA, RG 10, vol. 6892, file 487/28–3, pt. 1 (Belleville Daily Intelligencer, 4 August 1907)

29 David Boyle, “The Killing of Wa-sak-apee-quay by Pe-se-quan and Others,” Annual Archaeological Report; being part of an appendix to the report of the minister of education, Ontario (Toronto 1907), 91–121; Morton I. Teicher, Windigo Psychosis, A Study of a Relationship between Belief and Behaviour among the Indians of Northeastern Canada (Seattle 1960), 74; Chief Thomas Fidler and James R. Stevens, Killing the Shamen (Moonbeam, Ont. 1985); James R. Stevens, “Zhauwuno-Geezhigo-Gaubow,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13: 1901–1910 (Toronto 1994), 1128–30

30 Harwood Steele, Policing the Arctic (Toronto n.d.), 215, 355

31 W.W. Baldwin, “Social Problems of the Ojibwa Indians in the Collins Area in Northwestern Ontario,” Anthropologica 5 (1957): 77; R.W. Dunning, Social and Economic Change among the Northern Ojibwa (Toronto 1959), 52

32 HBCA, B.220/a/046, fos. 2d, 21, 35d, 36d, 37d, 38d, 40d, 41, 46, 55d, 56d, 60d, 61d, 62, 62d; B.155/b/002, fos. 3d, 15d, 16d, 25d; B.093/a/011, fo. 63d, 66, 66d, 67, 67d, 68, 89d

33 HBCA, B.220/a/047, fos. 95, 111, 124–8

34 William McInnes, “Report on a Part of the North-West Territories of Canada Drained by the Winisk and Attawapiskat Rivers,” in Reports on the District of Patricia, ed. Willet G. Miller (Toronto 1912), vol. 21, pt. 2, 134; Edward S. Rogers, “Notes on Lodge Plans in the Lake Indicator (Lac Indicateur) Area of South-Central Quebec,” Arctic 16, no. 4 (1963): 219–27

35 D.B. Dowling, “Report on the Country in the Vicinity of Red Lake and part of the Basin of Berens River, Keewatin,” Canada, Geological Survey, Annual Report 7, pt. F (1894): 31

36 J.B. Tyrrell, “Hudson Bay Exploring Expedition, 1912,” Ontario Department of Mines, Annual Report 22, pt. 1 (1913): 167

37 Willet G. Miller, “Reports on the District of Patricia,” Ontario Bureau of Mines, Report 21, pt. 2 (1912): 131

38 A. Irving Hallowell, “Notes on the Material Culture of the Island Lake Saulteaux,” Journal de la Société des Américanistes 30 (1938): 134

39 Ibid., 132

40 F.W. Waugh, Ethnographic fieldnotes on Northern Ojibwa for 1919, MS, Canadian Ethnology Service, Ottawa

41 Anderson, Fur Trader’s Story, 178

42 Alanson Skinner, Notes on the Eastern Cree and Northern Saulteaux (New York 1911), 123

43 Waugh, Ethnographic fieldnotes

44 John J. Honigmann, “The Attawapiskat Swampy Cree, An Ethnographic Reconstruction,” Anthropological Papers of the University of Alaska 5, no. 1 (1956): 47

45 James Redsky, Great Leader of the Ojibway, Mis-guona-gueb (Toronto 1972), 118

46 Bishop, The Northern Ojibwa, 71

47 Edward S. Rogers and Mary B. Black, “Subsistence Strategy in the Fish and Hare Period, Northern Ontario: The Weagamow Ojibwa, 1880–1920,” Journal of Anthropological Research 32, no. 1 (1976): 11–13

48 HBCA, B.022/b/001, fos. 12–14d

49 Bishop, The Northern Ojibwa, 90

50 J. Hambleton, “Caviar for Celebrities,” The Beaver, outfit 275 (June 1944), 46

51 HBCA, B.220/a/048, fo. 91

52 NA, RG 10, vol. 6819, file 490/2–17

53 Bishop, The Northern Ojibwa, 94

54 Hunter, Canadian Wilds, 29

55 HBCA, B.220/a/051, fos. 55–7

56 Bishop, The Northern Ojibwa, 95

57 Lerchs, “The Sandy Lake Cree/Ojibwa,” 57

58 Anderson, Fur Trader’s Story, 163

59 Bishop, The Northern Ojibwa, 95

60 Anderson, Fur Trader’s Story, 188

61 Baldwin, “Social Problems of the Ojibwa Indians,” 86

62 R.W. Dunning, Social and Economic Change among the Northern Ojibwa (Toronto 1959), 11

63 Mary Black Rogers and Edward S. Rogers, “Adoption of Patrilineal Surname System by Bilateral Northern Ojibwa, Mapping the Learning of an Alien System,” in William Cowan, ed., Papers of the Eleventh Algonquian Conference (Ottawa 1979), 198–230

64 Skinner, Notes on the Eastern Cree and Northern Saulteaux, 150

65 J. Garth Taylor, “Northern Ojibwa Communities of the Contact-Traditional Period,” Anthropologica 14, no. 1 (1972): 22

66 Ibid., 21

67 Ibid., 25

68 Rogers and Black, “Subsistence Strategy in the Fish and Hare Period,” 39

69 Dunning, Social and Economic Change, 57

70 HBCA, B.220/a/048, fo. 39

71 A. Irving Hallowell, “Some Empirical Aspects of Northern Saulteaux Religion,” American Anthropologist 36 (1934): 390

72 HBCA, B.220/a/048, fo. 73

73 J. Garth Taylor, Ethnographic fieldnotes from Webiquie, 8 July–22 August 1970; 14 July–8 August 1972, MSS

74 Baldwin, “Social Problems of the Ojibwa Indians,” 65

75 Edward S. Rogers, The Round Lake Ojibwa (Toronto 1962), B44

76 Ibid., D17; E.S. Rogers, “Natural Environment – Social Organization – Witchcraft, Cree versus Ojibwa – a Test Case,” in Contributions to Anthropology, Ecological Essays, ed. David Damas (Ottawa 1969), 24–39

77 J.M. Cooper, “Notes on the Ethnology of the Otchipwe of the Lake of the Woods and of Rainy Lake,” Anthropological series, Catholic University of America, no. 3 (1936): 1–29

78 Skinner, Notes on the Eastern Cree and the Northern Saulteaux, 154

79 A. Irving Hallowell, “The Passing of the Midewiwin in the Lake Winnipeg Region,” American Anthropologist 38 (1936): 51

80 Dunning, Social and Economic Change, 16

81 Robert E. Ritzenthaler, “Southeastern Chippewa,” in Handbook of North American Indians, vol. 15: Northeast, ed. Bruce Trigger (Washington, D.C. 1978), 756