During the 1830s and 1840s, several thousand Algonquian-speaking Indians living in the United States immigrated to Upper Canada. The United States government passed the Indian Removal Act in 1830, permitting it to relocate eastern American Indians. Accordingly, that government pressed Amerindian groups to sign treaties with provisions stating that their communities must migrate to the prairie country west of the Mississippi River. This clause generated great dissatisfaction. Many Amerindians south of the Great Lakes refused to leave and remained in what became the states of Indiana, Michigan, Wisconsin, and Illinois. But pressures for their removal mounted. In 1837 the U.S. government informed the Indians that no further annuities would be given until they complied with the terms of the treaties.1 By moving north they could remain in the Great Lakes area.

The British policy of giving gifts to its North American Indian allies also encouraged Indians to settle in Canada.2 For many years the Crown annually provided the “Western Tribes,” as the British Indian Department called the Amerindians of the Upper Great Lakes, with gifts. Until 1828 the British had used Drummond Island as the northern distribution point. In 1829 the location was shifted to neighbouring St. Joseph Island. From 1830 to 1835 they made the distribution at Penetanguishene on Georgian Bay. Beginning in 1836 the British ended the distribution at Amherstburg, the southern point, and at Penetanguishene, in favour of one central location, Manitowaning on Manitoulin Island. Here the Western Indians assembled each summer to receive their gifts. In 1836 nearly 2 700 Indians arrived and received presents.3 A year later 3 700 Ottawa, Ojibwa, Potawatomi, Winnibago, and Menominee came from the United States.4 Anxious to end this continued expenditure, the British officials announced in 1837 that the distribution of presents to Indians who continued to reside in the United States would soon cease.5 A second notice in 1841 stated that unless the “Visiting,” or American, Indians settled permanently on the British side of the border by 1843, they would lose their eligibility.6 After 1843 only “Resident” Indians, those who lived permanently within British territory, received presents.7

The fact that many Algonquians living south of the Great Lakes had relatives in Upper Canada also encouraged migration, as did the similarity of Upper Canada’s natural environment to their former homeland. Finally, many American Indians regarded the British as fairer in their Indian policies than the Americans.

Many Algonquians (with the Potawatomi apparently in the majority) made their way into Upper Canada.8 The population estimates of these arrivals vary somewhat. One authority, for instance, believes that some 2 000 to 3 000 Potawatomi arrived from Wisconsin, Michigan, and Indiana between 1837 and 1849.9 Another has estimated that the different groups of Indians who moved into Upper Canada in this period (including the Potawatomi) numbered no more than 1 500 to 4 000.10 During the next four decades, roughly from 1840 to 1880, the immigrant Potawatomi slowly became settled on existing reserves in present-day Southern Ontario. Walpole Island at the northern end of Lake St. Clair became an early refuge.11

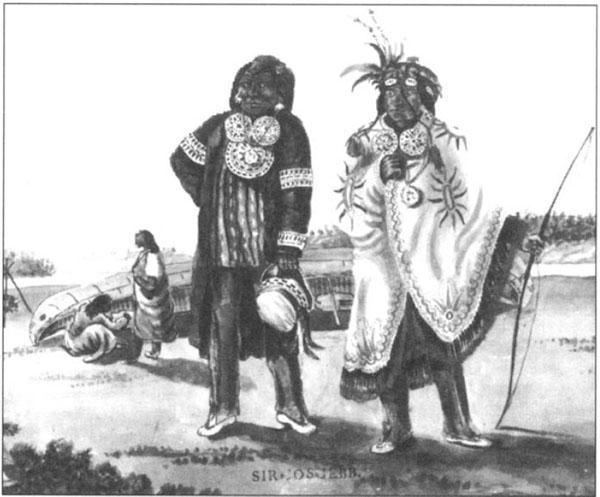

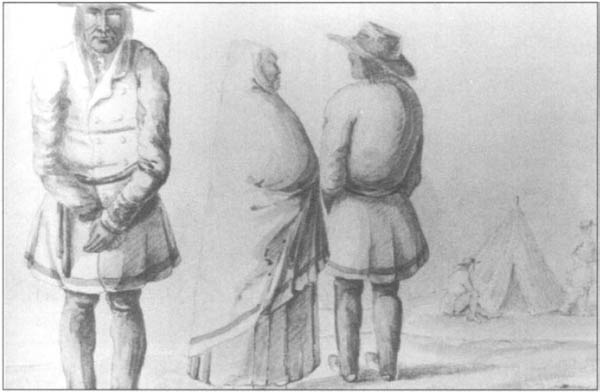

“Two Ottawa Chiefs who with others lately came down from Michillimackinac Lake Huron to have a talk with their great Father, the King or his representative.” They are wearing clothing of trade cloth and trade-silver ornaments. Watercolour (1813–20) by Sir Joshua Jebb.

National Archives of Canada. C-114384

Information regarding the movements and final destinations of the Ottawa (or Odawa) is somewhat less precise than the data for the Potawatomi. Nevertheless, it is known that in 1836, when some Ottawa signed a treaty with the U.S. government for their remaining lands in Michigan’s lower peninsula, a large number of them, particularly the Roman Catholic converts, migrated to Manitoulin Island.12 Apparently, some had preceded them, for five or six families of Ottawa already resided at Wikwemikong and had one to two hectares of land under cultivation.13

Andrew Blackbird, an Ottawa who acted as interpreter for the U.S. government, claimed that more than half of all his people in the United States had, by 1840, immigrated to Canada.14 Further negotiations with the U.S. government to alienate land and dissolve their tribal governments induced more Ottawa to leave Michigan for Manitoulin Island and Georgian Bay in 1855.15 The Ottawa primarily settled on Manitoulin and Walpole islands. As some of the Potawatomi had, others found their way to reserves on Georgian Bay, such as Cape Croker, Christian Island, and Moose Deer Point, and to Rama on Lake Simcoe. By the late 1870s, a few had moved to Parry Island and most likely to other locations in Southern Ontario.16

The international border meant little to a group like the Ottawa, who had lived on both sides of the Great Lakes at the time of first European contact. In the mid-seventeenth century the Iroquois raids had forced them to migrate. Now, like the Ojibwa (called Mississauga on the north shore of Lake Ontario by the British settlers), who had expelled the Iroquois around 1700, the Ottawa returned to their former homeland.

In the mid-seventeenth century the Iroquois had also dispersed many Nipissing as well as the Algonquin who at the time of European contact had resided in Southern Ontario (see chapter 4). Some returned, however, to settle in the summers at Lake of Two Mountains (Kanesatake or Oka) and to use their hunting territories in the St. Lawrence valley. As early as 1807, some Algonquin settled at Golden Lake in the western Ottawa valley, their community gaining reserve status in 1870. Although the Algonquin claimed land west of the Ottawa River, it was the Ojibwa17 who in 1923, after years of litigation and protests, signed the Williams Treaty (see chapter 6).18

Government officials and Christian missionaries in the nineteenth century strongly believed that the Indians must become “civilized.” Once government officials moved the Native people onto reserves, they were convinced that they would soon become Christian farmers like their Euro-Canadian neighbours. To assist the Indians in farming, the Indian Department built them houses and supplied equipment, seeds, and stock.

The Wesleyan Methodists, the Anglicans, the Baptists, the Roman Catholics, and the Moravians had, in many ways, a more immediate impact upon the Aboriginal way of life than the Indian Department officials. They lived with their converts and with those they wished to add to the fold.19 Furthermore, some of the missionaries were of Native ancestry, a fact which no doubt assisted them when dealing with their people.

The missionaries experienced many setbacks, but in time they made nominal converts of many Algonquians.20 The churches considered conversion to Christianity, a “British” education, and the adoption of farming together formed an integral whole that, when imposed upon the Indians, would render them “civilized.” The converts attended church services, held family prayers and Bible readings, and participated in camp meetings. Yet a number of Algonquians maintained their traditional religion, and even the “converted” did not necessarily abandon their former belief system.

The Methodists began to proselytize during the mid-1820s, their first convert being Kahkewaquonaby (“Sacred Feathers”), or in English, Peter Jones, a twenty-one-year-old Mississauga of mixed ancestry. Raised to the age of fourteen among his Mississauga mother’s people, he had then lived with his non-Native father and his family until he was twenty-one. Bilingual and bicultural, he became the Methodists’ spokesperson. As a Native Methodist preacher he helped to recruit a number of talented Ojibwa converts as preachers, interpreters, and schoolteachers, people such as John Sunday, Catherine Sunegoo Sutton, Peter Jacobs, Henry Steinhauer, George Henry, George Copway, and Allen Salt.21

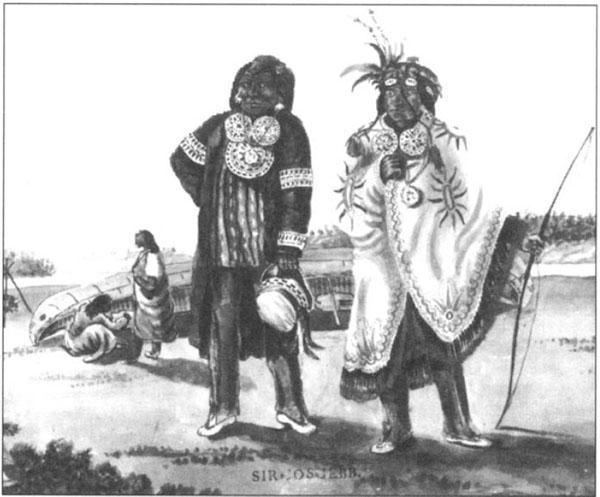

Sacred Feathers, or the Reverend Peter Jones. This engraving appears as the frontispiece of Jones’s History of the Ojebway Indians (London 1861). It would have been drawn about the time of his second British tour, 1837–38.

Although some of these individuals (Jones and Salt, for example) had one white parent, they stressed their Native ancestry. Peter Jones was the most important Native missionary in Upper Canada for over more than a quarter of a century. With the assistance of the Methodists and funding from the Indian Department, obtained from the sale of their lands as well as from their annuities, the Mississauga Christians built a model village at the Credit River twenty kilometres west of York (Toronto) in 1826. The Methodists established other mission stations, which led the Upper Canadian government to establish several government-sponsored agricultural villages. Until his death in 1856 Jones acted as a religious leader and, at the same time, as a chief of his people. He and his band moved in 1847 to the Six Nations Reserve on the Grand River, where they acquired land at what they termed “New Credit,” where they live to this day.22

Guided by Jones and others, the Methodists extended their mission westward. In 1832 John Sunday visited Sault Ste. Marie, and shortly thereafter Methodist missionaries commenced work on Manitoulin Island. Peter Jacobs undertook missionary work in what is now northwestern Ontario and Manitoba, but he later returned and settled at Rama on Lake Simcoe.23 Allen Salt also laboured in what is now northwestern Ontario, but in 1883 he returned to minister to the people of Parry Island on Georgian Bay. Three years later the band appointed him secretary-interpreter. He remained at Parry Island until his death in 1911.24

Although not as active among the Indians of present-day Southern Ontario as the Methodists,25 some Anglican clergy did become involved. The Reverend William McMurray ministered to the Ojibwa about Sault Ste. Marie from 1832 to 1839. The year after his arrival, he married Charlotte Johnston,26 of Ojibwa and Irish descent and a sister of the wife of Henry Schoolcraft, the United States’ Indian agent at Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan.27 In 1838 an Anglican missionary arrived at Manitowaning; in 1841 one was appointed to serve the Indians living on Walpole Island.28

The emigration of Roman Catholic Ottawa from Michigan to Manitoulin Island in the 1830s established that faith there, just before the Methodist missionary outreach weakened in the early 1840s. Roman Catholicism has since become the dominant Christian denomination among the Indians living on Manitoulin Island and on the north shore of Lake Huron. By 1836 a Roman Catholic missionary lived amongst them and a chapel had been built. In the 1840s Jesuit missionaries arrived to serve the Manitoulin mission and the Indians about Amherstburg and Beausoleil Island in Georgian Bay.29

The Methodists’ greatest rivals in Indian mission work in the 1830s and 1840s were the Roman Catholics. This watercolour by William George Richardson Hind shows a Catholic religious service on the north shore of the St. Lawrence River, 1861.

John Ross Robertson Collection, Merropolitan Toronto Reference Library

During the mid-nineteenth century the fur traders remained a strong presence on Georgian Bay. In the 1830s and 1840s Penetanguishene continued to be an important fur trade centre. The Hudson’s Bay Company dominated the trade farther north, having a number of posts in operation, such as those at Timiskaming, Matagami, Michipicoten, La Cloche, and Sault Ste. Marie. The company, however, faced opposition from a growing number of freetraders.30

By the mid-1830s many of the Algonquians in southern Upper Canada lived in permanent farming settlements. Governor Sir Francis Bond Head, however, judged the civilization policy a failure and advocated the migration of the Indians from present-day Southern Ontario to Manitoulin Island, in imitation of the Americans’ removal program. In 1836 Head persuaded the Ottawa and Ojibwa living on Manitoulin to allow Indians living elsewhere to move to the island.31 He selected the Saugeen Indians living south of the Bruce Peninsula for eviction and settlement.32 That same year he approached the Delaware who had come to Upper Canada from the United States in the 1790s. He induced them to give up fifteen square kilometres of their land, granted to them some four decades earlier, in exchange for an annuity.33 A year later, in response to Head’s actions, approximately 150 Delaware left Moraviantown and Muncey, not for Manitoulin Island but for Kansas.34

After Head’s recall to England in 1838, the colonial authorities allowed the Algonquians of Upper Canada to remain in their existing communities. Nevertheless, the Upper Canadian politicians continued to press the Indians to give up more unceded and reserve lands. In 1850 the Ojibwa along the north shore of Lake Huron and about Georgian Bay signed the Robinson-Huron Treaty, which became a model for the later numbered treaties such as Treaties No. 3 and No. 9 (by which most of Northern Ontario was ceded to the Crown). The Robinson-Superior Treaty, for lands north of Lake Superior, followed that same year.35 In 1854 and 1857 the Indians of the Bruce Peninsula surrendered much of their remaining unceded land.36 Finally, in 1862, Manitoulin Island was officially surrendered to the Crown with the exception of the most easterly portion.37

Map 7.1

Area of the Robinson Treaties, 1850

Drawn by Marta Styk, University of Calgary; adapted from “Area of the Robinson Treaties, 1850,” in R. Surtees, The Robinson Treaties, Treaty Research Report (Ottawa 1986), 49

Map 7.2

Indian Villages and Reserves, Manitoulin Island

From R. Surtees, Indian Land Surrenders in Ontario, 1763–1867 (Ottawa 1984), 107

Although the Amerindians might retain the right to hunt, trap, and fish on Crown land, the amount of Crown land continually diminished as settlers bought land for farms. On their new properties the newcomers cut down the forest and fenced in the cleared lands. Even when game remained, an Indian who hunted on private property could be charged with trespass.

Between 1820 and 1845, at certain locations, the Algonquians by necessity cleared land, built homes, and raised a few crops. As the Indians became settled in villages, the churches established schools for the children. In 1826 the Methodists began at the Credit River settlement one of the first schools among the Algonquians of Upper Canada.38 During the 1830s and 1840s the Methodists, Anglicans, and Roman Catholics established schools at their mission stations throughout southern Upper Canada. Schools for Indian children resident within any organized county or township came under the Common School Act of 1824, by which they could obtain provincial grants (after Confederation in 1867 the Indian schools became the sole responsibility of the government of Canada).39

Peter Jones in 1844 petitioned the government on behalf of the Credit River Indians to establish manual labour schools, where students would remain in residence for the entire year to receive religious as well as specific job training. The Methodists established two such residential schools in the late 1840s, one at Munceytown, near London (the Mount Elgin School), and the second at Alderville, near Rice Lake. The Anglicans had operated a school at Brantford, the Mohawk Institute, since the 1830s. In 1874 the Anglicans also built an industrial school at Garden River. After it burned down shortly after its completion, the government set up the Shingwak Home for Indian boys and the Wawanosh Home for Indian girls in neighbouring Sault Ste. Marie.

With financial help from the government, the churches in the late nineteenth century established additional schools for Indian children, usually day schools. By 1884 seventy-five day schools and six Indian residential schools existed in the province. Attendance, however, fell short of 100 percent. From time to time band councils tried to remedy the situation, no doubt at the urging of government and missionary officials. In 1891, for example, the Parry Island Band Council passed a resolution fining parents fifty cents a month for each of their children not in school. On occasion band councils appointed truant officers, but apparently they had little success. Similarly, strapping for misconduct was detrimental to school attendance, for, with the support of their parents, students refused to attend.40

In spite of the influx of immigrants and the destruction of large sections of Upper Canada’s forests, the Algonquians secured much of their food through hunting, fishing, and gathering.41 This was especially true of those living in the more remote areas of Southern Ontario.42

Big game – moose, deer, and bear – was at times important, but to what extent is difficult, if not impossible, to determine. Deer, no doubt, supplied the most meat of the three species. As the land was opened for cultivation, more forage became available for deer and accordingly they increased in numbers. In the 1840s Peter Jones wrote: “I have known some good hunters in one day kill ten or fifteen deer, and have heard of others killing as many as twenty.”43 Moose, on the other hand, were now deprived of their appropriate habitat, and they decreased in numbers. Bear, although never as numerous as deer, were a welcome addition to the larder, as each animal possessed large amounts of bear fat, relished by the Algonquians.

Smaller game such as grouse, waterfowl, hare, and rabbit supplied some food at certain times of the year. Until their extinction in the late nineteenth century, passenger pigeons were an important food source. Beaver supplied both food and furs. The Indians sought other fur-bearing animals primarily for their pelts.

Hereditary hunting and trapping territories had apparently come into existence by the late eighteenth century.44 Most likely the Algonquians considered as private property only the fur-bearing animals secured from these areas, whose pelts they sold to Euro-Canadians. Animals, if taken for home consumption, were no doubt free to all. Each Ojibwa group had its particular section of country which its members visited each year to secure food and furs. Important areas were the Credit, the Thames, and the Moira river valleys and the lands adjacent to the lakes between Lake Simcoe and the Bay of Quinte.45 By 1860, however, the newcomers controlled these areas. Farther north, the Indians continued their old subsistence and fur-trapping activities until at least the end of the century, with specified areas claimed by each hunting group. The Lake Simcoe (Rama Reserve) and Parry Island Indians hunted in the Parry Sound–Muskoka districts, where each family possessed its own territory.46

From the mid-nineteenth century onward the Algonquians possessed various items of store-bought hunting and trapping equipment. While guns became the principal weapon for hunting big game and waterfowl, at what date they became common is not known.47 When hunting deer during the fall, a number of men cooperated together to pursue the deer with dogs48 or to build a drift fence.49 Although the Ontario government enacted legislation in 1892 that restricted the hunting of deer to the first two weeks of November, Indians killed deer at other times of the year as necessity dictated and the opportunity presented itself. Under the terms of their treaties, the Indians argued that they retained the right to hunt on unoccupied Crown lands and on their reserves. For securing smaller game, they utilized snares, deadfalls, and steel traps.50 They used iron-headed, single-barbed spears to take muskrat in the late winter.51

Although hunting and trapping supplied a considerable amount of food, fishing was probably a more reliable food source for the greater part of each year.52 Fish populations did not fluctuate greatly in number, and quantities could be preserved for future use. The Parry Island Indians, for instance, salted and stored trout in large barrels. Fish prepared in this manner could be eaten safely until the following May.53 The Indians near Sault Ste. Marie had access to the abundant whitefish fishery in the St. Mary’s River. Here they lived summer and winter on whitefish.54 Lake Simcoe had an abundance of whitefish, trout, and bass. On the north shore of Lakes Ontario and Erie, the Algonquians fished in the same areas that they used for hunting.55

Fishing equipment consisted of several different items – the gill net, used extensively, the hook and line,56 and at Sault Ste. Marie the dipnet for taking whitefish from the St. Mary’s River.57 The Amerindians occasionally employed a form of harpoon to take fish,58 and they commonly speared them. The spear shaft might be ten to thirteen metres in length.59 The spearhead was of iron, sometimes of trident form; at other times it was two-pronged.60 During the summer and fall before freeze-up, the Indians speared fish at night from canoes. They used a jacklight, which originally consisted of birchbark placed in a cleft stick and set on fire, to attract the fish.61 Later, they added an iron basket, mounted on the bow of the canoe, in which they placed and then ignited pine knots. In this century they substituted flashlights and electric lights. Although jacklight fishing became illegal, the practice continued for a time.

Once the ice became thick enough to support a human’s weight, the Indians undertook “peep hole” fishing. Both men and women engaged in this winter activity. First the individual cut through the ice with an iron chisel, making an opening oval in shape and about half a metre wide on the surface, then gradually enlarging it. Once the hole was prepared, the Indian erected a small tent above it. Those fishing remained in their enclosures for three or four days until they had caught enough fish to make it worthwhile to return home. The Indians used a small wooden lure in the form of a minnow, stained blue,62 to attract carnivorous fish. Once within range, the Indian attempted to spear the fish. Occasionally, in addition to pike and trout they might spear a sturgeon.63

Peep-hole fishing continued into the twentieth century. Although the government outlawed it, individuals fished in this manner practically under the noses of the game wardens. They constructed spears with a detachable head of three hardened steel points forming a trident. The shaft would be left concealed at the fishing site, the head, however, could easily be hidden. Seeing no long spear handle in evidence, the warden assumed that only a hook and line was used. On their arrival at the site, the men and women, out of the warden’s sight, could easily assemble their spears and fish in their time-honoured manner. Trout were the principal species taken. Those who caught them often sold the larger ones in neighbouring communities for fifty cents for each half-kilo. They used the pike they speared for home consumption.

Ojibwa fishing at the Sault Ste. Marie rapids, using a dipnet. A painting by William Armstrong, 1869.

National Archives of Canada, C-114501

Spearing Salmon by Torchlight, by Paul Kane. Although Kane’s painting is of the Menominee Indians on the Fox River in present-day Wisconsin (in 1846), it could easily have been painted around the 1830s or early 1840s during the spring or fall salmon runs on the Credit River. The Mississauga used the same fishing technique as their fellow Algonquians of the Upper Great Lakes.

Royal Ontario Museum, 910.1.10

Gathering wild plants provided another source of food. Wild rice and maple sap were perhaps the two most important crops,64 although the Indians also gathered berries (especially blueberries) whenever and wherever possible. The harvesting of wild rice occurred on Rice Lake, the western shore of Lake Ontario, and the Bay of Quinte. Among the Indians of Chemong Lake near Peterborough, and no doubt elsewhere, each family had its own sugar bush and a common occupation of the women each spring was the preparation of maple sugar.65

Equipment for collecting crops was minimal. Probably the Amerindians used ricing sticks for gathering wild rice66 and a wooden scoop for collecting cranberries. At Parry Island the band council eventually outlawed the use of the scoop, as it damaged the cranberry bushes.67 The Indians, however, needed more equipment for collecting and processing maple sap. The workers used cedar spiles to tap the maple trees for their syrup, which was collected in birch-bark containers and then transported to the sugar house on a stone boat pulled by a horse. Here, the syrup was stored in large elm or basswood troughs, each about a metre long, to await boiling down in large brass or iron kettles. The Indians stored the prepared sugar in birchbark boxes approximately 45 to 120 centimetres long and 30 centimetres high. Before the sugar hardened, the workers poured it into wooden moulds that they had carved in various designs.68

The Algonquians’ means of transportation varied according to the seasons. In summer the Indians traditionally used birchbark canoes, from roughly 5 to 10 metres in length and up to 1.2 metres in width. They continued to build them into the early twentieth century.69 For emergencies, the Indians constructed elm-bark canoes.70 Eventually, however, the destruction of the mature forests in Southern Ontario deprived them of the large birch trees that provided the bark to cover their canoes. Other means of water transport now came into use. Dugout canoes began to be built towards the end of the last century in the Georgian Bay area71 and earlier farther south.72 As the people became more sedentary, such craft became more useful. Dugout canoes, constructed in about two weeks, were made either of pine or of basswood. The canoe builders hollowed out the hull by scraping, aided by the use of fire. Dugouts were large enough to carry two or three people and a few supplies.73

Indian Sugar Camp, engraving by J.C. McRae of a watercolour by Seth Eastman. The women usually left for the maple sugar groves during the final muskrat hunt in the spring.

From Henry Schoolcraft, Historical and Statistical Information Respecting the History, Condition and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States, 6 vols. (Philadelphia: Lippincott, Grambo & Co. 1851–57), 2:58

Rowboats in turn replaced dugouts. In the Georgian Bay area, sailboats, in addition to rowboats, came into common use. They were from approximately five to seven metres long and were two-masted with a jib. Although the Algonquians used cedar in much of the construction, they employed hardwood for the ribs. They utilized the inner bark of basswood to manufacture rope and to make the rigging. The workers applied pine gum to seal any cracks. The use of sailboats declined during the early twentieth century.74

Water travel decreased after the construction of roads. Although the government extended colonization roads northward during the 1840s and 1850s,75 highways remained few in number until after the First World War. With the arrival of the car in the early twentieth century,76 the Indians further adjusted their modes of transportation. They gradually acquired cars, but in the meantime they used horses and wagons.

Sleds, toboggans, and snowshoes continued in widespread use, even after the roads were built. The snowshoe style was that typical of the Ojibwa77 and others of the area – rounded in front and pointed at the rear, with two crossbars. The frame was ash, with the lacings prepared from deer hide, cut spirally starting from the outer edge to obtain a long continuous thong. To lace the snowshoes, they used a wooden or bone needle, pointed at both ends and with a hole in the centre. The frames might be painted various colours and tassels of coloured yarn attached as ornamentation. A market developed for birchbark canoes and snowshoes for recreational use among the non-Native population.

Although the Indians continued hunting, trapping, and fishing, the imposition of game laws in the late nineteenth century made it more difficult for them to do so.78 The continuing reduction in the amount of lands available to Indians curtailed hunting and fishing. As this occurred, the Indian Department and the missionaries exerted further pressure on the Algonquians to adopt agriculture. They provided instruction and gifts of farming tools.

The most critical obstacle to the transition from Indian hunter-gatherer to Indian farmer lay in the perception of the land. Although for over 200 years Europeans had attempted to erode the Indians’ traditional beliefs and values, especially spiritual ones, many in the nineteenth century retained the old perception of the relationship between people and the land. Peter Jones, for instance, could write of the Indian elders in the mid-nineteenth century: “They suppose that all animals, fowls, fish, trees, stones, etc., are endowed with immortal spirits, and that they possess super-natural power to punish any who may dare to despise or make any unnecessary waste of them.”79

Yet, in spite of the obstacles, a number of Algonquians did become farmers. The success of the Credit River “experiment” in the 1820s promoted further experiments. By 1829 Indian superintendents, such as Thomas Anderson, promoted agriculture among their Native charges.80 The Indian Department purchased farm equipment and livestock for the Indians and hired farm instructors to demonstrate and teach agriculture. The desire to farm increased the need for additional fertile land. The village sites on Snake Island and at Balsam Lake, for example, were eventually abandoned in a search for land that had the potential to support farming. New settlements were established on Georgina Island and at Lake Scugog respectively.

The Algonquians raised a variety of crops. Indian corn was an important source of food, since ground corn formed one of the main dishes. The Parry Island Indians made bread and a gruel from dried corn ground very fine with a mortar and pestle. In making corn bread, they wrapped the ground corn in cornhusks and buried these in hot coals to bake.81 Beans were another important crop; others included peas, potatoes, and, in time, squash, carrots, cucumbers, rhubarb, and turnips. The Indians raised wheat and timothy hay for the cattle, and oats and some wheat for the horses. In addition, each family might have an orchard, primarily of apple trees. From the apples, they made cider.82

Initially, and for some time after the adoption of farming, the Indians on some reserves worked with only hoes and spades. In time, the Algonquians acquired oxen and later horses as draft animals to pull ploughs, hayrakes, and harrows.83 The Algonquians could make none of these items themselves and, accordingly, purchased their farm equipment from local merchants or obtained it from the Indian Department.

The Algonquian farmers kept some livestock – oxen, cattle, sheep, hogs, and horses, plus chickens, turkeys, geese, and ducks. From the livestock, the Indians obtained meat, dairy products, leather, and animal power for doing work in their fields. Geese assisted in the gardening by eating the weeds.84

As the Algonquians took up farming, buildings became more numerous, varied, and permanent. Dwellings at first consisted of log cabins. As early as 1827, the Mississauga of the Credit, about 200 individuals, occupied twenty substantial log homes.85 As the Algonquians obtained permanent houses, they bought, or modelled on those of the settlers, more and more of their household furnishings. Yet, they continued to make some of their former handicrafts – splint baskets, birchbark boxes, wooden spoons, mortars, and cradle-boards.

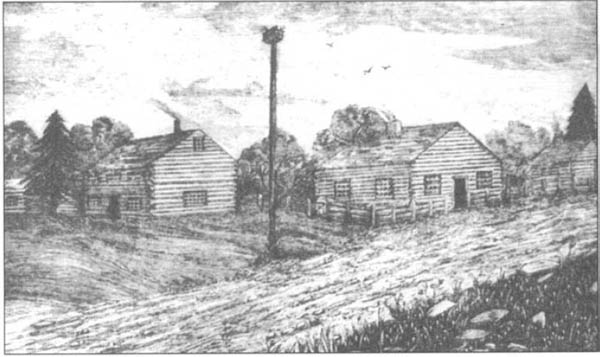

Indian Village at the River Credit in 1827 – Winter. The houses were dressed log cottages with two rooms, like the type the settlers built as a second home after five to ten years on their farms. Two families occupied these houses, each family having its own room.

From Egerton Ryerson, “The Story of My life” (Toronto 1883), 59

The Algonquian farmers now required other structures, such as squared-timber barns and sheds and root cellars for the storage of root crops during the winter. As missionary activities increased, the communities constructed churches and schoolhouses, and for government business, they built council halls.

Nevertheless, as long as the Algonquians travelled frequently in search of country game and furs, they made traditional lodge-type dwellings that could be quickly erected and easily moved.86 Perhaps the most common of these was the conical lodge, but dome-shaped and ridge-pole lodges87 were used as well, each covered with birchbark, sometimes cedar bark,88 rush mats,89 and/or canvas. Trappers might erect a conical lodge covered with evergreen boughs and floored with cedar boughs,90 such as the artist Paul Kane painted near Sault Ste. Marie in 1845. Canvas tents eventually replaced the traditional portable lodges.

As the Algonquians adopted farming, their annual cycle of activities changed. In early spring, however, the collecting of maple sap remained the principal task. Occasionally, they sold some of the maple syrup and sugar to local merchants, but the Indians kept most for home use. At the same time, some trapping of muskrat and beaver might be undertaken in the neighbourhood of the sugar bush. Trapping was continued on into May after the sugaring had come to an end. When the ice left the lakes and bays, waterfowl returning from the south formed a welcome addition to the diet. The Indians then set gill nets to take a variety of fish, such as pickerel and whitefish. Later during June and July, sturgeon would be speared.

Ojibwa lodges near Sault Ste. Marie, 1845: a painting by Paul Kane.

Royal Ontario Museum, 912.1.9

Once spring trapping and the gathering of maple sap ended, the people farmed. Those who had moved to the sugar bush, and the men who had gone any distance to their traplines, returned home. By now the ground had thawed and they could ready it for planting. Once the communities had planted their crops, the people engaged in other activities except when the gardens needed weeding. Fishing was not neglected, and throughout the summer and into the fall, the Algonquians collected a great variety of berries, such as strawberries, raspberries, blueberries, blackberries, and cranberries, the last being harvested in September. In the fall the harvesting of the crops and the collecting of the wild rice took place. In October (after the harvest) the Indians took trout with spear and jacklight, by trolling, and with hook and line. Some hunting might be undertaken for deer and ducks. At the same time, the Algonquians trapped mink and otter.

During the winter months, the Indians’ workload decreased somewhat. Nevertheless, they had to take care of their livestock, clean and repair their farm equipment, and, of course, cut large quantities of firewood for heating and cooking. They also did some trapping. In the nineteenth century the Algonquians carved axe handles, pike poles, brooms and wooden bowls, ladles and shovels, which they sold in nearby towns, using the money to pay for the forthcoming Christmas festivities. The Algonquians celebrated Christmas with a large feast. They had another feast at New Year’s, when they also held a dance.

Gathering Wild Rice, a watercolour by Seth Eastman. Each family had the right to collect wild rice from a particular locality. One person guided the canoe, while others beat the kernels free.

James Jerome Hill Reference Library, St. Paul, Minnesota

Cornelius Krieghoff’s painting of an Amerindian woman with her handicrafts for sale, in the 1830s.

Royal Ontario Museum, 977.314.1

Early in the new year, the women spent some of their time making craft items, such as quill boxes, splint baskets, and moccasins for the summer tourist trade. The communities did some trapping, hunting, and fishing during mid-winter. As winter drew to a close, the Indians made preparations to collect maple sap, the activity that signalled the end of another yearly round.91

The Algonquians of Southern Ontario’s social organization became modified in the mid-nineteenth century. Although the nuclear family had always been an important and basic Algonquian social unit, the adoption of farming strengthened its hold. Each family became, theoretically, independent of all others, residing on its own farmland, occupying its own house, and raising its own food. A household might consist of the husband, wife, and children as well as one or more dependents, such as an elderly parent. As polygamy was no longer practised, the couple was monogamous.92

Even in the most Christianized of the Ojibwa families at the Credit River, such as that of Peter Jones, the children continued to receive Indian names.93 The parent would ask an elder to bestow a name upon the infant. If the elder accepted the honour, he or she became the child’s godparent. The name chosen was usually that of some noted ancestor or was derived from some natural feature or event, occurrence at birth, or personal characteristic.94 It could be given at a feast. Individuals might change their name during their lifetime.95

The Algonquians loved children and always indulged them during the early years of their lives. But as the children grew older, the Algonquians introduced subtle means of ensuring their obedience. As soon as the children could help the adults in their daily tasks, their parents expected them to do so. Girls, because of the nature of the work expected of them, might start assisting in household duties at a younger age than the boys, who aided their fathers in farm work, hunting, trapping, and fishing. In addition to helping at home, children attended school if one existed in the community. Some children might be sent away to a residential school.

On reaching puberty, boys and girls in the nineteenth century, even in a number of Christian families, underwent a vision quest. Originally, the young person left the group and fasted for ten days in some secluded spot, such as on the top of a high hill or upon a special platform erected in a tree. With the development of village life, the youth might be sequestered in the attic of the sponsor’s home. If successful, the individual received a vision in which a spirit appeared, one who became the youth’s guardian for life.96

Usually not long after their son had undertaken the vision quest, his parents arranged for his marriage. They contacted the parents of one of the local girls whom they considered suitable. If the girl’s parents agreed, the couple would generally consent. A church wedding marked the occasion. After the ceremony, the community offered the young couple gifts such as livestock and built them a log house.

A well-defined distribution of labour existed between the sexes throughout their adult life. Although the division did not need to be rigidly adhered to, the men generally hunted, trapped fur-bearing animals, and did the wood working, whereas the women undertook the household tasks of cooking, sewing, and the working of hides. Both men and women, either individually or jointly, went fishing, gathered berries and maple sap, and tended to the farm work. Old age brought increased respect and a lessening of the labours imposed upon those of younger age. The elders could indulge their grandchildren, especially in recounting the legends of their people. These entertaining stories instructed the young people in the ways of their ancestors and on the proper way for them to behave.

When a death occurred, the community mourned its loss. The corpse was prepared for burial and a coffin constructed. Usually, a Christian burial service was performed, at the church and/or cemetery. Christian converts placed a cross or headstone at each grave and erected a picket fence about the plot. Some families continued the tradition of erecting a grave house over the burial.97 Here, individuals might make offerings to the spirit of the deceased.

A number of nuclear families, each forming a household, made up a settlement. In the mid-nineteenth century more and more Algonquian families came to reside in settlements, really clusters of several or more houses and associated farm buildings, one or more churches, schoolhouses, and a council hall. Adjacent to each homestead lay the orchards, pastures, and garden plots in which the Indians grew various crops. Overshadowing the cleared fields stood the primeval forest. Openings here and there might contain productive berrying grounds.

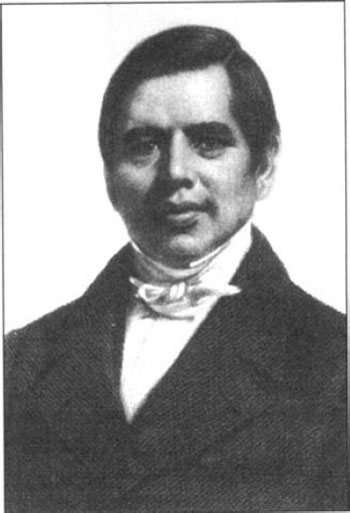

The non-Christian Indians’ form of burial. Seen here are graves at Munceytown. The non-Christian Indians believed that the soul lingered around the body for some time before taking its departure. Before placing the body within the coffin, the relatives of the deceased would bore several holes at the head of the coffin. They believed that this would permit the soul to go in and out at pleasure.

From Peter Jones, History of the Ojebway Indians (London 1861), opposite 99

An Indian Christian burial ground, at the Lower Village, Parry Island, Georgian Bay, 1890.

National Archives of Canada, PA-68316

A web of kinship connections linked households together. On various occasions, these groups cooperated with one another. During the spring when the Indians prepared maple sugar, several related families often resided together in the sugar bush and prepared the sugar together. At other times, several families assisted each other in farm tasks that required more hands than a single household could muster.

The families that comprised a settlement frequently intermarried with each other, as other Native communities often were separated from them by considerable distance. In the mid-nineteenth century, and no doubt for some time thereafter, marriage between cross-cousins (father’s sister’s children and mother’s sister’s children) was a preferred practice, but missionary opposition probably reduced the incidence of such unions. Clan mates, however, could not wed. Clans among the Algonquians in Southern Ontario, whether a postcontact development or not, apparently at this time had no other function than to regulate marriage. Ojibwa clans had such designations as “Caribou,” “Beaver,” “Otter,” “Eagle,” “Crane,” “Birchbark,” and “White Oak,” and were patrilineal, the children taking the clan affiliation of their father.98

The Credit River Methodist Mission. Peter Jones’s wife, Eliza Field Jones, made this sketch shortly after her arrival at the Credit Mission in the fall of 1833. The Credit River Mississauga used the building on the left as both a school and a council house. The building to the right is the church. On the top of the flagpole is a small house for martens to nest in, their presence being considered a good omen.

From Egerton Ryerson, “The Story of My Life” (Toronto 1883), opposite 72

The Algonquians of Southern Ontario in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries held feasts, dances, and sporting events at various times of the year. Some of the feasts and dances had a spiritual component. Feasts occurred at Thanksgiving, Hallowe’en, Christmas, the New Year, the 6th of January, and on Easter Monday,99 the most important occurring at Christmas and the New Year. On these occasions the Indians often performed a concert, sang songs, and made speeches. The speaker might recount legends of the past.

The elders organized the feasts, with the oldest in charge. The master of ceremonies made a speech and said grace; then everyone ate. After the meal, the women cleaned up and each man lit his pipe and told a story. Sometimes feasts were family affairs and held at home. Others were community functions held in the community hall.

Those who attended the feasts and dances wore their best clothes, which were based upon the current Euro-Canadian styles. Nevertheless, clothing styles did depend to some extent on the proximity to settlements, as well as on the individual’s acceptance of the larger society’s ways.100

Titus Hibbert Ware completed this sketch of Ojibwa at Coldwater, north of Lake Simcoe, in 1844. The Ojibwa men adjusted to the settlers’ style of clothing more easily than did the women, but they still wore moccasins and colourful sashes around their waists in the mid-nineteenth century.

Metropolitan Toronto Reference Library, T14386

Some individuals wove certain items of traditional dress, such as deerskin leggings and jacket, each having the appropriate fringes. These practices continued much later in the north, into the twentieth century. Many individuals wore deerskin moccasins, especially when snowshoeing. Moccasins for special occasions were sometimes decorated with beadwork or embroidery. The Algonquians wore costumes that symbolized their Indian ethnic identity for special events such as official meetings with government representatives.

Clothing to express one’s Indianness often mixed Native and European traditions, further modified by innovations conceived by the individual. The Algonquians in Southern Ontario, for instance, later in the nineteenth century added a feather headdress based on those worn by the Plains Indians. They also, on occasion, decorated their top hats with feathers and carried a pipetomahawk and fire bag.

Maungwudaus (George Henry), a daguerreotype probably taken around 1850. Originally from the Credit River, Maungwudaus had a very successful stage career in the late 1840s and early 1850s.

National Archives of Canada PA-125840

The Algonquians usually decorated their jackets and leggings, whether made of cloth or hide, with beaded floral designs. Beading became, in time, the most popular decorative technique, replacing silk embroidery and quill work. The women prepared the deer hides, then sewed the material using three-cornered needles and (for thread) the sinew from the deer’s back. Frequently they attached deer hoofs to costumes to produce a rattling sound.101

The Algonquians performed dances among themselves and for Euro-Canadian audiences, and on occasion troupes from Upper Canada travelled as far as Europe. Maungwudaus, one of the most celebrated showmen, performed with his troupe before the King of France. The Indians’ repertoire included the “wabeno,” “shoe,” “pipe,” and “war” dances. To accompany the dances, the troupe drummed and sang.

The Algonquians had games for all ages. Children enjoyed the cup and pin game and horseshoes. The women played a ball game of their own. Each had a short pole about one metre long. With her pole the player propelled two hide balls joined together by a short piece of thong. Each ball was filled with sand and decorated with a fringe along the sewn edges. The women, organized into two teams, competed for possession of the balls and attempted to convey them to their opponents’ goal at the opposite end of the field. Since the late nineteenth century, the Indians have played both softball and baseball. Often the reserve teams competed with teams from surrounding settlements.102

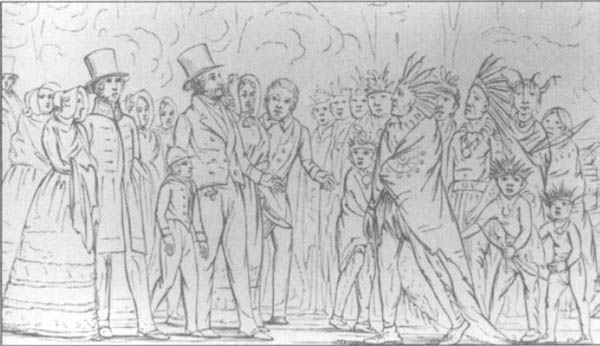

King Louis Philippe of France, his queen, and the Belgian royal family are introduced to Maungwudaus and his troupe in the park at St. Cloud Palace just outside Paris.

Drawing by George Catlin from his Catlin’s Notes of Eight Years Travels and Residdence in Europe, with his North American Indian Collection, 3d ed. (London 1848), vol. 2, pl. 19, opposite 288

Although the Algonquians certainly could manage their own affairs, the government of Canada thought otherwise. The government’s ultimate goal became the total assimilation of the Amerindians into the larger society. In 1876 it consolidated the legislation relating to Indians into the “Indian Act.” A central principle of the legislation lay in its enfranchisement provisions, procedures by which an Indian could cease to be a member of an Indian nation and become a full citizen of Canada, giving up his or her separate Indian legal status (see chapters 9 and 10).

In 1884 Parliament added a section to the Indian Act that spelled out the form of government each settlement or “band” in eastern Canada should follow. Each was to elect a chief and one or more councillors (based on their community’s population) every two or three years. The government intended to impose a democratic European-style form of government upon the Indians and to do away with the old political structures. The Indian Act stipulated that the chief and councillors of each settlement would be responsible to the local superintendent of Indian affairs.

Numbering the Indians at Wikwemikong, Manitoulin Island, 16 August 1856. A drawing by William Armstrong. Chief Assiginack is shown naming the Indians to Captain Ironsides, the Indian superintendent. They stand in front of Ironsides’s office (in the frame building to the right). Indian homes appear on the left, and in the background one can view the Roman Catholic church.

Metropolitan Toronto Reference Library, T16028

By the twentieth century, the elective system prevailed, and where it did, band officials earned a salary. In addition to the elected officials, there might be one or more messengers appointed by the chief to assist him in his various duties. The band paid them an annual salary of from five to fifteen dollars. The messengers gathered provisions from the residents of the settlement for the sick, widows, and families unable to support themselves, and as well, they collected money to pay for funerals. The council appointed a secretary-treasurer and police, if needed, to assist the council in its work. It hired other salaried officials such as school trustees, forest bailiffs, truant officers, and school caretakers as required. The band paid for everything out of its own funds, derived from the monies received from the sale of timber and the fees band residents paid for the right to cut and sell cordwood.103

The chief, councillors, and all concerned residents met, as a rule, once a month in the council hall or, if none existed, in the schoolhouse. Council meetings might deal with a wide range of topics: from land allocation to resource management, from treaty concerns to the admittance of new members, from feasts to funerals.104 Each settlement might also have an unofficial leader, who made suggestions, gave advice, and led in certain affairs, most prominently in religious ceremonies.105

New Credit election poster, 1896. Dr. Peter E. Jones, a medical doctor who trained at Queen’s University, was one of the first status Indians in Canada (if not the first) to become an Indian agent. He was a son of the Reverend Peter Jones.

National Archives of Canada C-97585

Above the local level of band government, the various Southern Ontario Algonquian settlements formed an association known as the Grand Council or General Council. The associated bands met periodically in one of the member’s communities, sometimes on their own initiative, at other times at the instigation of government officials. To solemnize council meetings in the mid-nineteenth century, the Algonquians displayed their wampum belts,106 recited the story each depicted, and smoked the traditional and sacred stone pipes.107 The Grand Council concerned itself with the federal government’s administration of Indian policy. The council petitioned the government regarding various grievances, such as treaty rights.108

Although as a rule the Indians pursued peaceful means to rectify wrongs committed by (or perceived to have been caused by) the invading Euro-Canadians, overt aggression sometimes erupted. In the mid-nineteenth century, trouble occurred at Mica Bay in 1849 and on Manitoulin Island during 1862–63.109 In the case of Mica Bay, mining companies had begun operations in an unceded area. In reaction, the Ojibwa seized the property of the Quebec and Lake Superior Mining Company in an attempt to force government intervention on their behalf. The Mica Bay incident drew attention to the government’s neglect of its responsibilities under the Royal Proclamation of 1763, with its provisions for the proper purchase of Indian lands. Subsequently, the government negotiated the Robinson Huron and Superior treaties in 1850.110 Similarly, the Indians of Wikwemikong would not surrender the east end of Manitoulin Island in the early 1860s and continued to claim exclusive fishing rights to the coastal waters. When non-Natives attempted to force an end to the dispute, violence erupted.

Great Grand Indian Council, Curve Lake, Ontario, 15 September 1926.

Archives of Ontario, Acc. 13709–15

In the mid-nineteenth century Christian missionaries actively worked among the Indians with remarkable outward success. The converted Indians, as well as the curious among the non-converts, often attended the summer camp meetings. Some took a more active role in church affairs, and as previously mentioned in this chapter, several became ordained Protestant ministers. Churches representing one or more Christian denominations were built in many Native communities. The Indians participated in baptisms, marriage rituals, burial services, and other Christian ceremonials. Yet, in spite of their best efforts, the Christian missionaries did not eradicate all traditional religious beliefs and practices. Rather, many went underground. The Indians generally withheld knowledge of their religious activities, as they did not want their old ceremonies (which many fervently believed in) ridiculed, laughed at, or condemned; they had too often experienced this sort of reaction from the newcomers.

In the mid- and late nineteenth century the Algonquians politely listened to the missionaries but did not necessarily accept all they said. Certain of the Christian teachings had for untold centuries been a part of the Indians’ religion; other aspects of Christianity seemed absurd from the Native point of view. The Algonquians, for instance, did not believe in proselytizing and thought it strange that the Euro-Canadians wanted to force everyone to believe in one god of their own creation. On the other hand, the Amerindians respected the right of every individual to believe and pray in the manner he or she thought right. Nevertheless, by the early twentieth century, the Algonquians of Southern Ontario had become nominal Christians, few being classified as “pagan.”

Traditionally the Algonquians believed that many of the animate and inanimate objects that existed in the world around them contained a spirit or spiritual force. They also believed that other spirits inhabited the universe as well.111 Spirits included such beings as the Thunders; Windigo, a man-eating giant; Mishi-pishew, the Great Lynx; and the Memegwesi, little men who lived inside cliffs and paddled stone canoes.112 The Indian, therefore, was not alone in the world. The spirit world often controlled many of the Indian’s actions.

The Algonquians interacted with the spirit world in a variety of ways. Traditionally they made the appropriate sacrifices or offerings – a white113 or a black dog, birds, or tobacco114 – to the spirits. They also sought to establish a personal contact with the supernatural world through the vision quest, described earlier in this chapter. Youths undertook vision quests, but they could be undertaken as well at other times in life. Spirits also came to an individual in his or her dreams. At such times they gave counsel and advice. Through the instructions of the spirits, an individual acquired the necessary knowledge whereby he or she could prepare a personal medicine bag. The bag was made of an animal skin or woven of fibres, and in it were kept the ritual medicines designated by the spirits.115

Through the vision quest and by means of dreams, individuals acquired power as a result of their contact with the supernatural world. This power could be used in a variety of ways for both good and evil. Those individuals, men and women alike, who received more power than others specialized in one or more of such rituals as the Shaking Tent ceremony. Four or more specialized roles existed, each performed by a distinct religious leader.116 Through these intermediaries, the average person could obtain communion with the spirit world.

One class of religious leaders included those who had received the appropriate power to perform the Shaking Tent ritual. The tent consisted of six or eight poles erected vertically in the ground in a circle about a metre or so in diameter. A wooden hoop encircled the poles near the top. Sometimes there was a second hoop farther down. This framework was covered, with the exception of the top, with either birchbark, hide, or canvas or a combination of these materials.117 The tent was constructed prior to each performance, which could be held only at night. When evening fell, the Shaking Tent diviner entered the prepared structure and called upon the spirits to assist him. Generally, if not always, the individual in need of help arranged for the ceremony for which he or she had paid a fee. By means of the performance, lost objects or missing persons could be located or an enemy eliminated.118

The Ojibwa of Southern Ontario also practised the wabeno ceremony, known as the “morning dance.” The performance, conducted by a member of another distinct class of religious leaders, had deep significance and was held each spring. First, the organizers made a dance floor by removing the branches of a tall tree and clearing the surrounding ground of saplings, brush, and debris. The participants had to fast beforehand and cleanse themselves thoroughly. The performance was held at dawn – although some contended that the participants danced all night – at which time those who had gathered began to dance around the tree to the accompaniment of a special drum. The wabeno leader, an elder male, acted as the drummer and led the dance. The children preceded the young adults, with the elders coming last. As a dancer passed the tree, he or she, at a signal from the drummer, touched the trunk. The dance continued until all had performed this act. They held the wabeno ceremony to thank the “Great Spirit” for help rendered during the course of the past year. At the same time, the participants requested continued assistance in the year to follow, abundant farm yields, and a bountiful supply of meat and fish. The dance ended about midday, and all joined in a feast, the principal dish being bear’s meat, with beaver meat and fish as well. For “butter” the Algonquians used sturgeon oil.119

The Midewiwin, a society of men and women who had received supernatural powers to cure the sick, apparently existed among some Algonquian communities in Southern Ontario. Information about the society in this area, however, remains fragmentary and sparse. It is not known whether or not the society was exactly the same in Southern Ontario as elsewhere. The anthropologist Diamond Jenness described the Midewiwin lodge as a large rectangular enclosure with stakes and brush for the walls and without a roof.120

Similarly, little is known about the ritual significance of the poles with carved faces near their tops erected in some Algonquian villages, or about the White Dog feast.121 No doubt these rites were directed to the spirits, as were various sacrifices made with tobacco, birds, and white and black dogs.122

In addition to the Midewiwin society members who healed the sick, other individuals specialized in particular cures. Certain men and women had the power and knowledge to prescribe various herbal medicines,123 while others practised the art of bloodletting. To perform bloodletting, the practitioner had a lancet,124 the tip of a cow horn (with which to draw the blood once the cut had been made), and a small container with the medicines to be applied to the cut. Other healers withdrew (with the aid of a bone tube) the “substance” causing the illness. They applied one end of the tube to the patient’s afflicted area. By sucking on the other end, the healer drew out into his or her mouth the foreign objects that had caused the sickness.125

By 1900 Euro-Canadians had settled throughout Southern Ontario. Farmers had cleared much of the land, lumbermen had cut over large tracts of forests, and railroads linked together the growing urban centres and towns of the hinterland.126 No longer could the Indians move freely or flee to areas beyond the newcomers’ influence. The great majority had no choice but to remain on their reserves and obey, at least outwardly, Indian Affairs personnel and the Christian missionaries. Under the pressures exerted by the newcomers, the Algonquians became enmeshed within the fabric of two cultural traditions, that of their ancestors and that of the new arrivals from across the Atlantic. In the years to come, they reached their own accommodation with the newcomers.127

After Canada entered the First World War in 1914, many Amerindians, including a number of Algonquians from Southern Ontario, made a valuable contribution. Out of 20 000 treaty Indians in Ontario, over 1 000 enlisted, of whom nearly 600 were Algonquians from the southern half of the province. As a result, a number of Southern Ontario Indian communities had very few of their able-bodied men at home during the war years.

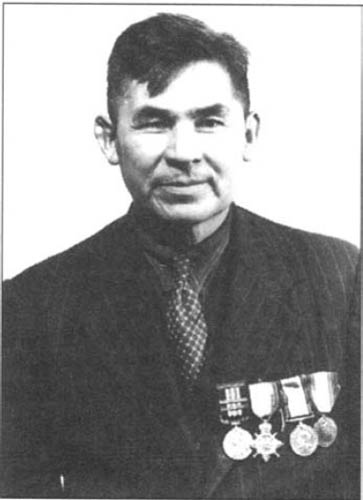

Once overseas, many of the Algonquian soldiers became renowned sharpshooters. Accounts of the number of kills by Cpl. Francis Pegahmagabow of Parry Island vary, to as high as 378. Johnson Paudash of Rice Lake and the brothers Samson and Peter Comego of Alderville, near Rice Lake, also became noted sharpshooters.128

The Amerindians at home contributed to the war effort. Many gave freely to the Canadian Patriotic, Red Cross, and other war funds. Each band raised varying amounts, ranging from $25 to $1 000. In all, the Indians of Southern Ontario contributed approximately $9 000. The women of the Saugeen Reserve on Lake Huron also formed a branch of the Red Cross Society and sent overseas various items needed by the troops. No doubt other Indian communities did likewise. As the war went into its second, then third, then fourth year, the need for greater quantities of food arose. Subsequently, the Indians on the reserves increased production, even bringing back under cultivation lands that had for a time lain idle.129

Francis Pegahmagabow, Ojibwa, on a visit to Ottawa, 1945.

Candian Museum of Civilization, 95292–3

Although the war disrupted their lives, it brought little obvious change to the Indian communities. Farming methods remained essentially the same. Horses and oxen continued to supply the operating power. The Indians grew the same crops. They still lived in squared-timber and frame houses, and wore clothing similar to that worn by their Euro-Canadian neighbours. At home they made their own tools and utensils as they had since time immemorial. The Algonquians went regularly to church and the children attended elementary school, usually on the reserve. They appeared completely integrated within the dominant society, but in reality many traditional attitudes and beliefs remained and they honoured their old spiritual beliefs.

A group of soldiers, many of them Ontario Native people, before going overseas in the First World War. Photo taken in the North Bay area.

Archives of Ontario Acc. 9164 s15159

By the early twentieth century fewer Algonquians lived in Southern Ontario than at any time since the arrival of the Europeans. The death rate so exceeded the birth rate that some Euro-Canadians believed that within a couple of decades the Indians would vanish biologically, and that the survivors would disappear culturally through intermarriage and assimilation into the larger society.

Increasing amounts of medical aid and other forms of assistance, however, helped to arrest declining numbers and slowly reversed the trend. The Indian population began to increase in the thirties. In 1934 approximately 30 500 registered Indians lived in Ontario. Twenty years later the total number had risen to 35 000.130

The First World War accelerated the pace of change for the Algonquians. The experiences that so many of the men, individually and collectively, had off the reserve as members of the Canadian armed forces proved a powerful catalyst for change. Those who returned had been introduced to many novel experiences, not the least of which was, for a moment, to be treated as equals and not as “children” and wards of the state. For the returning veterans in particular the world was no longer to be confined within those boundaries that marked off the reserves. Henceforth, greater interaction and association with non-Indians occurred.

Amerindian houses, Wikwemikong, Manitoulin Island, 1916.

Photo by F.W. Waugh, Canadian Museum of Civilization, 36778

Ojibwa family, Chemung (Curve) Lake, Kawartha Lakes, 1910.

National Archives of Canada, C-21152

Although farming continued in many Amerindian communities, it declined in importance after 1920.131 The farmland on most Southern Ontario reserves was submarginal and unsuited for mechanized farming. On the more fortunate reserves the Indians lacked the necessary funds to secure the additional farm machinery needed to compete successfully in commercial farming.

The “allotment” or “location” system also hindered the development of profitable farming. Eventually, the continual subdividing of land among family members made the farms too small. On the other hand, an individual could acquire the allotments of others, thereby making farming profitable for himself but depriving others of the opportunity. Each reserve had too little farmland to meet the needs of an expanding population and of mechanized agriculture.132

The automobile also inhibited farming. Wherever roads were built to connect the reserve settlements with surrounding communities, the Indians wanted cars. They could purchase cars through the sale of their livestock, but once they had parted with their cattle, they could obtain no replacements. Indian Affairs disapproved of these transactions and was not prepared to subsidize the purchase of cars.133

The pull of the city also helps to explain the decline of Indian agriculture in Southern Ontario. Greater employment opportunities in nearby communities and urban centres attracted more and more individuals. Improved transportation made such work possible. If employment was nearby, individuals could commute daily; if further away, they could still return home on weekends.

Although farming continued to decline in the 1920s and 1930s, the Department of Indian Affairs, still operating in the mind-set of a different era, continued to promote agriculture among the Indians. Federal administrators at headquarters in Ottawa misunderstood the new realities of life on the reserve. What the Indians needed in the 1920s and 1930s was an increase in the Department of Indian Affairs’ aid and assistance.134 Although welfare or relief payments for Indians throughout Canada reached a peak in 1937–38 and dropped only slightly during the fiscal year 1938–39, the per capita cost for Indians in Ontario was only $4.68.135

The Indians did not become dependent on welfare in the 1930s. Some migrated to urban centres to make a living, and those who remained at home found seasonal employment in the lumber camps, on the railroads, as commercial fishermen, as domestics, in the mines, and in other forms of employment.136 At Dokis Reserve on the French River, for example, the band leased its timber rights but with the stipulation that Indians be hired.137 In addition to seasonal jobs and welfare, many of the Native people obtained a certain amount of their food from the land by hunting, fishing, and gardening.

Throughout the first half of the twentieth century, the federal government largely neglected Amerindians. Indian Affairs officials, of course, pursued their policy of assimilation of the Indians into the dominant society, but with little government funding behind them. The Department of Indian Affairs made education compulsory in 1920 for all Indian children between the ages of seven and fifteen, which increased enrolment. But the limited amount of funding given to the Indian school system, as well as student resentment of its assimilationist aims, led to limited academic success. Very few Algonquians in Southern Ontario continued on to secondary school.138

The educational system included local reserve schools as well as the church-run residential schools. Basil Johnston, an Ojibwa from Cape Croker, has written an entertaining account of his school days in the 1940s at the Jesuit-run residential school at Spanish, on the north shore of Lake Huron. Although the discipline at the school was harsh, students had their own means of getting back at the administrators.139

The family still remained the principal means of teaching the children about the world around them. In the early twentieth century, however, the extended family no longer served as the strong social unit that it had been in the nineteenth century. As the nuclear family became more autonomous, children often did not have the opportunity for intimate contact with their elders. Many parents believed that their children should find their rightful place in Canadian society, which meant that the knowledge of the elders was not stressed.

The Algonquians of Southern Ontario rarely performed their traditional ceremonies in the 1920s and 1930s. When they did so, it was out of the sight of the Euro-Canadians. The Native people attended church and outwardly conformed to Christian doctrines, yet many still opposed the total assimilation advocated by the government of Canada and the Christian churches.

In the Native communities, the residents, particularly the younger school-educated Indians who had knowledge of English and the ways of the dominant society, began to demand better treatment. They wanted to retain their special status and be provided for adequately under the Indian Act and the treaties. They believed that such assistance was just compensation for what their ancestors had lost. The negotiations preceding the signing of the Williams Treaty of 1923 (see chapter 6) reflected this new attitude.

For over fifty years some Ojibwa had contended that their ancestors had never ceded a large portion of Southern Ontario. The territory in question extended between Lake Ontario and Lake Nipissing and included many square kilometres of rich farm and forested land. The area was said to have been the hunting grounds of the ancestors of the claimants who represented seven Ojibwa communities – Christian Island, Georgina Island, Rama, Mud (Curve) Lake, Rice Lake, Alnwick (Alderville), and Scugog. Since the 1860s individuals from these reserves had repeatedly petitioned the government to rectify this oversight. Finally, the government acceded to the Ojibwa’s request and in 1923 made a settlement. For half a million dollars (to be divided among the bands) and a per capita payment of $25, Ontario believed it had acquired title to this land.140 In the negotiation process, however, both the federal and Ontario governments had overlooked the claims of the Algonquin of the Ottawa valley to the eastern section of the disputed territory. This omission surfaced in the 1970s when the Algonquin again brought forward their claim to their lands in the Ottawa valley.141

The Department of Indian Affairs’ response to the Ojibwa’s tactics in the Williams negotiations indicated its determination to complete the Indians’ assimilation into the dominant society.142 The department was furious that the Ojibwa had hired their own lawyers to present their case. In 1927 Parliament amended the Indian Act to make it, in effect, an offence to pursue land claims without departmental permission. The amendment forbade Native people to raise money without permission to investigate any of their claims against the government.143 Until the 1930s Parliament continually increased the powers of the superintendent general of Indian affairs. The Second World War, however,144 resulted in significant changes in the relationship between the Native people, the government, and Canadian society.

The Southern Algonquians contributed as much to the Second World War as they had to the First. Again many enlisted in support of the Canadian war effort, and this time Native women also joined the ranks. Ontario, of all the provinces, contributed the greatest number to the total of 3 000 status Indians who enlisted in the Canadian armed forces. A total of 1 324 men and 32 women signed up.145 Ontario Indians were represented in the Canadian Army in every rank, from private to brigadier-general (Milton Martin of the Six Nations).146 Many Indians from across the province served with distinction in the European theatre, and their exploits earned several medals and military distinctions. Not so fortunate were the many families who lost sons, husbands, brothers, and fathers during the fighting. An extraordinary example of the sacrifices made by one Ontario Indian family has been recorded for the Cape Croker Reserve. John McLeod first served in the First World War, and in the Second he enlisted in the Veteran Guards. His six sons and one daughter entered the forces. Two sons were killed in action and two were wounded overseas.147

Again, contact with the non-Indian world intensified. Overseas many experienced a racial equality they had not known at home. Max King, a Mississauga from New Credit, wrote from his base in Britain: “They [the local British] are really swell, working-class people and in their distress they show a spirit which we never find in Canada.”148 A number of Canadian Indian soldiers returned to Canada with British war brides. Through marriage with treaty Indians these women secured all the rights and privileges of registered Indians. In fact, in the eyes of the law, they (like all those under the Indian Act) ceased to be citizens and became wards of the Crown. They could not vote in provincial or federal elections, serve on a jury, or drink alcohol in a public place.149

For those who stayed at home, opportunities for city work multiplied through the need for a greatly expanded labour force. The war effort needed hundreds of thousands of male and female workers for the munitions factories and related war industries.150 At the end of the war, Native servicemen and women returned to a colonial existence on their reserves, ruled as they were under the rigid, dictatorial Indian Act. New voices would soon be heard. Native peoples called for their recognition as the original inhabitants of this land. A new generation of Algonquians, familiar with the dominant culture, fought in the decades to follow for their rightful place in society and for compensation for past grievances.

NOTES

1 James A. Clifton, A Place of Refuge for All Time: Migration of the American Potawatomi into Upper Canada 1830–1850 (Ottawa 1975), 32

2 Anon., Report on the Affairs of the Indians in Canada Laid before the Legislative Assembly 20th March 1845 (8 Victoria Appendix EEE A 1844–45), 34

3 Ibid., 35

4 Anna Brown Jameson, Winter Studies and Summer Rambles in Canada, 3 vols. (London 1838), 3:268

5 Ibid., 3:279–82

6 See Clifton, A Place of Refuge, 36

7 Paul Kane, Wanderings of an Artist among the Indians of North America (Toronto 1925), 7, 10–11

8 I. McCoy, History of Baptist Missions (Washington, D.C. 1840), 546; P. V. Lawson, “The Potawatomi,” Wisconsin Archaeologist 19, no. 2 (1920): 98

9 Clifton, A Place of Refuge, 34; James A. Clifton, “Potawatomi,” in Handbook of North American Indians, vol. 15: Northeast, ed. Bruce G. Trigger (Washington, D.C. 1978), 739

10 Lawson, “The Potawatomi,” 98, 102

11 Report on the Affairs of the Indians in Canada . . . 1845, 34

12 Johanna E. Feest and Christian F. Feest, “Ottawa,” in Handbook of North American Indians, vol. 15: Northeast, ed. Bruce G. Trigger, 772–86

13 Report on the Affairs of the Indians in Canada . . . 1845, 35

14 A.J. Blackbird, History of the Ottawa and Chippewa Indians (Ypsilanti 1887), 98

15 Feest and Feest, “Ottawa,” 779

16 E.S. Rogers and Flora Tobobondung, Parry Island Farmers: A Period of Change in the Way of Life of the Algonkians of Southern Ontario, Canadian Ethnology Service, paper no. 31 (Ottawa 1975), 278–9

17 Gordon M. Day, “Nipissing,” in Handbook of North American Indians, vol. 15: Northeast, ed. Bruce G. Trigger, 787–91; G.M. Day and Bruce G. Trigger, “Algonquin,” in Northeast, ed. Trigger, 792–7

18 George Brown and Ron Maguire, Indian Treaties in Historical Perspective (Ottawa 1979), 30; J.L. Morris, Indians of Ontario (Toronto 1943), 61–2; R.C. Daniel, A History of Native Claims Processes in Canada 1867–1979 (Ottawa 1980), 63–76

19 See Elizabeth Graham, Medicine Man to Missionary: Missionaries as Agents of Change among the Indians of Southern Ontario, 1784–1867 (Toronto 1975), 38

20 Benjamin Slight, Indian Researches; or Facts Concerning the North American Indians; Including Notices of Their Present State of Improvement, in Their Social, Civil and Religious Condition; with Hints for Their Future Advancement (Montreal 1844), 134–7; Margaret Ray, “An Indian Mission in Upper Canada,” The Bulletin: Records and Proceedings of the Committee on Archives of the United Church of Canada (Toronto 1954), 10–18; Jameson, Winter Studies and Summer Rambles, 3:227–32

21 See Slight, Indian Researches, 35ff.; Graham, Medicine Man to Missionary, 14–20; G.S. French, Parsons & Politics: The Role of the Wesleyan Methodists in Upper Canada and the Maritimes from 1780 to 1855 (Toronto 1962), chap. 6; and Donald B. Smith, Sacred Feathers: The Reverend Peter Jones (Kahkewaquonaby) and the Mississauga Indians (Toronto 1987).

22 Smith, Sacred Feathers, passim

23 Peter (Pahtahsega) Jacobs, “Extract of a Letter from the Same [i.e., Peter Jacobs], dated Lac-la-Pluie, Hudson’s Bay Territories, July 10th, 1844,” Methodist Magazine, 68, 205; Peter Jacobs, Journal of the Reverend Peter Jacobs, Indian Wesleyan missionary, from Rice Lake to the Hudson’s Bay Territory and return (New York 1858)

24 NA, Salt 1854–55 MS: Salt, Notebook; Christian Guardian, 8 February 1911; Rogers and Tobobondung, “Parry Island Farmers,” 302

25 Jameson, Winter Studies and Summer Rambles, 3:297

26 Ibid., 3:227; H.N. Burden, Manitoulin, or Five Years of Church Work among the Ojibway Indians and Lumbermen, Resident upon that Island or in its Vicinity (London 1895), 21

27 Report on the Indians of Upper Canada (“The Sub-committee Appointed to make a Comprehensive Inquiry into the State of the Aborigines of British North America, present thereupon the first part of their general report”) (1839; reprint, Toronto 1968), 44–5

28 Report on the Affairs of the Indians in Canada . . . , 1845, 34