Professional fly tier Pat Cohen shows off the face of a big Mohawk River carp—a face only a mother, or an angler, could love.

CHAPTER 5

The kayak fishing explosion really started in two places, right around the same time. The first was out in Southern California with kayak fishing pioneers Dennis Spike and Jon Shein chasing big-game species in saltwater. The other was in Florida in the ponds full of lily pads and giant largemouth bass with angler Ken Daubert.

“At four I was sneaking away to go bass fishing,” says Daubert, who got his start like the rest of us: with a pocket full of worms, standing on a drainage pipe fishing for bluegill with a hand line. After moving to Florida in 1982, Daubert started guiding on saltwater from a skiff. “One day I saw a kid with a kayak paddle across thick weeds,” he says. “It looked so easy.” From then on he guided less and kayak fished more. Pretty soon he became known around the country as one of the original pioneers of kayak fishing, penning his own book, Kayak Fishing: The Revolution, and inventing his own lure, the Bass FROG.

Daubert fishes from a kayak for the same reason many other anglers choose to fish from these little plastic boats. “I like shallow water,” he says. “Seeing the fish first, and then casting; the surface fishing. That’s why the kayak, it has that stealth factor.”

That closeness to the water and to the fish was the same reason I started kayak fishing. I originally bought the kayak to head out into the saltwater after big striped bass that I couldn’t reach from shore, but I soon started hitting the many freshwater ponds near my home and quickly became addicted. That stealth factor that Ken Daubert grew to love is the same tactic I use on a daily basis every time I’m fishing for largemouth bass, smallmouth bass, or northern pike from my kayak. Pairing the stealth of a kayak with the precision and natural presentation of a fly rod brought me over the edge and I’ve never looked back. Now every time I fish, whether close to home or on a trip, saltwater or fresh, I bring a fly rod.

Fishing for warmwater species is less high-adrenaline, less intense, than fly fishing from a kayak in saltwater, at least in general. Of course, there are times and circumstances when freshwater fishing is an all-out melee of action, but the atmosphere is much more relaxed when there are no tides and currents to consider and weather seems to roll in much slower, and there is generally less boat traffic or competing anglers to worry about. While some anglers focus all of their efforts on warmwater species and will plan full dawn-to-dusk days around them, I think they can also be the perfect fishery to hit for a quick trip before or after work or for introducing an angler to kayak fly fishing. With smaller fish (generally) and with less to think about, anglers cutting their teeth on kayak fly-fishing tactics and skills will have a much easier and more enjoyable time during the learning process—which means they’re more likely to love it after they become experts.

The thrills in warmwater fly fishing come in bursts separated by long, quiet moments. I once was fishing in upstate New York on a slow-moving warm river looking for big musky on the fly, just down the street from where a previous world record fish was caught. We had been lazily paddling upstream, casting gigantic flies towards structure and looking for signs of moving fish. The heat combined with staring into the murky, tannic-stained water had me fishing seemingly half asleep as cast after cast came up empty. When the first musky swirled on my fly, I nearly dropped the rod in surprise and panic, totally ruining any chance at actually hooking up. For reference, the swirl of a musky on your fly looks and sounds like a cannonball dive from a water buffalo. Revitalized and shaking, I cast towards the next log with extra focus. A smaller musky, though still a 30-inch fish, burst from underneath the wood and halted just inches from my fly, staring right into my eyes, through my soul. Before I had a chance to twitch the fly once more and get him to strike, the musky ghosted into the deeper, darker water and we never saw another fish that day. There’s no going back from an encounter with a big fish like that, and it’s hard to find that in any other form of fishing.

There’s no other fishery that lends itself so perfectly to kayak fly fishing than small ponds full of eager fish. A lightweight kayak that you can throw over your shoulder with one hand while carrying the rest of your gear in the other makes it possible to jump from pond to pond in seconds, which is something no other boat could do.

This is where I perfected my skills at kayak fly fishing, as Cape Cod, where I was born and raised, contains 365 lakes and ponds cut and shaped by the glaciers receding from the last ice age. When I look for a new pond that’s ideal for a lightweight run-and-gun pond-hopping mission, I look for water that I can cover in a single day. Larger lakes that take more than one day to cover every inch of water will fish much differently, as the fish will orient themselves on different structure and points than they would in smaller bodies of water. A pond is even better if access is tougher or requires hiking in, since nobody but a kayak angler would be back there.

The great thing about smaller ponds is that you can cover the entire pond in a day, so choosing where to start is less important because you’ll get to it all eventually. Regardless of that fact, though, I usually always try to put in on the downwind end of the pond, for two reasons. The first is because after a long day of kayak fishing, I’ll likely be tired and want the wind to carry me all the way back to the launch. Try doing that in a big, heavy boat.

The second and much more important reason is that wind tends to congregate bait, whether that’s shad or other kinds of baitfish under the water’s surface or bugs scattered on the surface. Fish follow the bait, so anglers looking to hook up should also follow the bait. Fishing the downwind side first either will let you start hooking up right away and begin to pattern what the fish are keyed in on or willing to bite, or will let you cross off that part of the pond first and move on to the next.

If the downwind side is not producing fish, which tends to happen when the water is colder, like in the spring, it may be because the fish are stacked up in the warmer waters of the upwind edges of the pond. This is where the most effective tactic for pond hopping comes into play: beating the bank. Not only is beating the bank an extremely effective tactic for catching fish around the spawn, or before the dog days of summer, but it can also be the most exciting way to fish. Pulling your fly through a shallow sand flat along the drop-off of a pond and watching a big bass come out of nowhere and slam it is truly unforgettable. I tend to circle the entire pond, casting to nearly any enticing structure or pattern that is within casting range. Besides drop-offs or edges leading into varying depths of the pond, fish may be locked onto structure, such as stumps, rocks, or downed trees, where they can hide and wait to ambush prey. In order to catch more fish, you have to imagine that your fly is the prey and then put it in the spot where it will most likely be ambushed.

The great thing about fly fishing from a kayak when beating the bank is that you can orient your position better and easier than someone in a bigger boat, or especially an angler wading on shore, ever could. If you’ve chosen a kayak that allows you to stand up, you’ll have the best vantage point for searching for edges and structure in the water, as well as spotting fish. Even if you can’t stand up in your kayak, the fact that you can rotate and maneuver the boat with the flick of your paddle means you can make a cast much sooner than an angler waiting to spin his big john-boat with a slow trolling motor.

Wind will constantly be a factor when fly fishing from a kayak, not just because it may affect your cast, but also because it will spin and move your boat much more drastically than if you were fishing from a bigger boat. If you’re fishing with a wind pushing your boat along the bank too quickly, there are two techniques to slow yourself down. You can either point your kayak into the wind, which will reduce the boat’s profile, thus giving the wind less surface area to push against, or you can use a drift sock. Since pointing your bow or stern into the wind tends to be only a temporary solution, or a solution for lighter winds, keeping a drift sock in your boat is a great idea. Essentially a drift sock is a small parachute that you attach to one end or side of your kayak and let drift behind you in the water. The open parachute will grab the water and create more drag, making it harder for the wind to push you along the water’s surface. If you don’t have a drift sock handy, many collapsible mesh nets will work, though not as well and efficiently.

While you’re fishing, your paddle should rest in a dedicated paddle holder or in your lap, right at your hip, which will keep the paddle out of the way but also accessible at the same time. If you’re fishing in windy conditions and must constantly correct your boat’s position between every cast, it makes more sense to leave it in your lap. If there is no wind or you like the speed at which the wind is blowing you, keeping the paddle out of the way in a dedicated paddle holder means you can really focus on fishing.

Controlling your boat while fighting a fish is where kayak fishing separates the pros from the rookies. Controlling a boat with one hand while fighting a fish with the other shows how much more skilled we really are compared to our big-boat brethren. If you’ve decided to store your paddle in a paddle holder, make sure it’s in a position that is easily reached with one hand. If you have to use two hands to retrieve your paddle, it will be useless during a fight with a good fish.

Whether the paddle is in your lap or in a paddle holder, controlling your boat while fighting a fish comes down to the same concept: leverage. With only one hand to paddle, you must rely on your body, specifically your waist. Your kayak’s gunwales can also assist in making sure your paddle shaft is at the proper angle to the water, using that as sort of a secondary axis. Imagine your fly rod in your right hand, a good bend in the rod and all your slack line put onto your reel. The fish is running and is trying to drag your kayak right into a downed tree, causing you to lose the fight. With your left hand, pick up your paddle from where it is sitting on your lap, near your hip. Your left hand should be in the same position along the paddle shaft that it would be for completing a normal forward stroke. Where your right hand would normally go, place that point along the shaft against the front of your right hip. Use your hip as the axis point as you push off with your left hand, causing the paddle blade on your right side to push against the water, spinning your bow to the right and moving the boat backwards. You can either continue to spin your boat in this manner and drift in front of the downed tree, or execute another stroke on your left side to move straight backwards.

To perform that same paddle stroke on the same side that you’re holding the paddle shaft on, slide your left hand up to where you would normally put your right hand for a forward stroke. This stroke is much more awkward and tricky than just paddling with one hand. Once your left hand is where you would normally put your right hand on the forward stroke, place the paddle shaft where your left hand would normally go on your left hip. Pull back on the paddle shaft and your hip will act as an axis for the shaft to rotate; your bow will be pulled towards the left and the boat will continue to move backwards.

If you’re standing and must use your paddle to maneuver your boat, your chest becomes that leverage point. There is some disagreement among anglers as to whether it is more difficult to paddle with one hand while sitting down or while standing up. I think it’s easier to get your paddle blade in the correct position while sitting down, but if you are standing up you have a trick up your sleeve for adding more power to your stroke that you don’t have sitting down (more on that in a second).

Picture the center of your chest, right at the sternum, that leverage point or axis on which your paddle must rotate. The angle of your paddle shaft will be much steeper when standing up, with the top paddle blade next to your head and the other in the water next to your kayak. If your fly rod is still in your right hand, for example, your left hand must hold the paddle at the tip of the paddle blade instead of the paddle shaft. This will give you much more leverage when executing the stroke itself.

In the same motion as if you were sitting down, pull back on the paddle blade with your left hand; the blade on your right side will push against the water and move your boat backwards. That extra power I mentioned earlier can come in handy if you’re fishing in current or in heavier winds and need to power your boat through some chop. As your paddle blade in the water starts to lose power, you can extend your knee towards the bow of your boat and create a secondary fulcrum point for your paddle shaft to rotate on. Driving the paddle shaft forward with your shin, just below the knee, can push your boat backwards even faster and ensure you’re in control of your boat, even if you have to paddle one-handed.

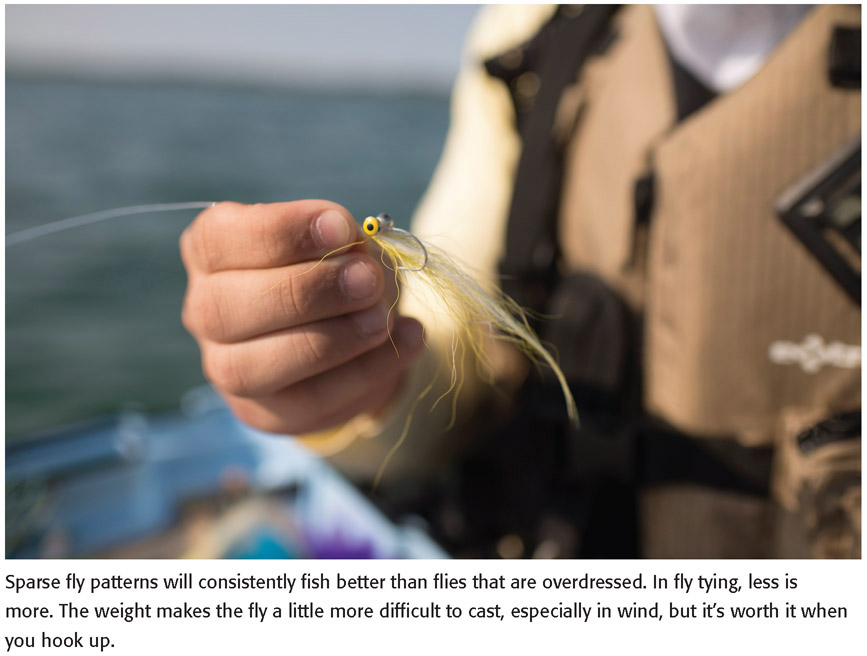

I like fishing with experts in their field. The more you fish with someone much better than you, the more you learn and learn fast. When it comes to fishing for bass and other warmwater species with a fly rod from a kayak, the most exciting way to fish is with a big, bushy bass bug, which is a fly that features more fur and feathers than you could imagine fitting on a single hook. Most bass bugs are designed with a buoyant head, usually made from deer hair or foam, followed by a tail and body made to add flash and movement to the fly. The combination of these materials creates a fly that rides on the surface of the water at rest, yet on the retrieve the fly will dart under the surface and shake or wiggle with a pulsating action that warmwater species simply can’t resist. The king of creating and tying these bass bugs and warmwater patterns is a tier named Pat Cohen.

I’ve had the privilege of fishing with Cohen a few times, the first time being when I met him in the back parking lot of a U-Haul dealership somewhere in upstate New York after driving four hours before the sun rose. Giant beard, gauges in his ears, and tattoos covering his body, I could tell he was my kind of fishing partner.

Putting in below a dam among a flock of bird-watchers, who were staring at us with annoyance and confusion, we paddled across the current into a cove of calm water, looking for carp. After paddling around for a bit not seeing a single fish, we hiked up to the top of a nearby cliff and scouted for signs of carp. Pockmarks littered the bottom, like chicken pox on a first-grader, signaling that carp were in the area. Near the opposite shore we could see a few big shadows moving through the water and we rushed back to our kayaks. While I couldn’t convince a carp to bite that day, Cohen hooked, fought, and landed a giant 20-plus-pound carp on one of his own creations, the CarpNado, a buggy pattern that has convinced carp from all over the country to bite, even though they are probably the pickiest eaters in freshwater.

Before he starts choosing his fly pattern du jour, though, Cohen likes to do a little research on the new waters that he’s going to fish, especially if it’s a small pond off the beaten path. After finding a choice-looking body of water on Google Earth or through word of mouth, he might even do a little scouting before he brings a fly rod, especially since some waters are too small to discern details on satellite images. “I try to do whatever homework I can at home from the computer, whether that’s Google Earth or a local Fish & Wildlife site,” he says. “Even on some of the forums, every once in a while you can catch a name of a small body of water that someone went on, something only the locals will know about.”

The next thing Cohen looks for is the structure, the key to discovering where the fish will be, and what kind of presentation will work best that day. “I’ll ask if there are weed lines, lily pads, areas of cattails, a little island of grass in the middle, or maybe fallen trees,” he says. Even the color of the water can be a hint as to the forage in the water, or what to expect from a new body of water that you might not have seen in your research. “I look at the color of the water to see how tannic it might be,” he says. “A lot of the small bodies of water around me tend to be swampy, kind of like flooded forests, so they tend to be really tannic, which tells me right away that the oxygen levels might be lower, which means the fish might not be as big.”

Signs like water clarity can start to paint the picture of your fly choice, especially when you have no other clues from your research to go on. One thing that helps an angler choose the right fly is knowing the local forage of a particular region, even in general terms. “I know in my area what the general forage is going to be for pretty much any body of water that I’m going to hit,” Cohen says. “I’ll go prepared for various kinds of baitfish and crayfish, or it could be a mouse pattern if I’m fishing topwater, and I try to bring some kind of insect, maybe a dragonfly nymph or damselfly nymph. When I go out on the water, I carry everything with me, including the kitchen sink. I try to go prepared for everything.”

On top of that, Cohen also likes to bring a few patterns that imitate smaller largemouth bass. “Largemouth are cannibalistic—they’ll eat other largemouth all day long,” he says. Other baitfish patterns that work well in Cohen’s area of upstate New York and anywhere around the Northeast region of the United States are perch, golden or silver shiners, and bream species like bluegill. Before you try to make a random guess as to the forage the fish are feeding on during a particular weather pattern or season, approach the water with the idea of scouting the forage first, before you look for fish. “Lets say I get out on the water and I find a school of baitfish,” says Cohen. “I don’t know what it is initially, but I see that they’re in the 4- to 5-inch range.” Pick a streamer—Cohen says the color doesn’t matter much as long as it’s the same size as what is present in the water—and make a few casts. “I’ll make ten or twelve casts with that, and if I don’t get a reaction or a follow or anything, I’ll stay in that same size range because I know that’s what’s there, but I’ll switch colors,” he says. If you’ve tried four or five colors without a strike or reaction, it’s time to switch. “I say OK, maybe they’re not eating this, maybe that was just that particular school of baitfish that was there,” says Cohen. When it comes to picking the next size of fly, he says to go for one extreme or the other. “I’ll either go really big and try to get a reaction bite, or I’ll go much smaller and just see what I can find,” he says. “From there a pattern starts to form, and eventually I’ll start to know what these fish are targeting in on.”

When you’re throwing big baitfish patterns or bass bugs, all of which will likely feature terrible air resistance and make it harder to cast, Cohen likes to use a bigger fly rod than other freshwater anglers. “Most of the time I have an 8-weight and a 9-weight with me in the kayak, and I like to have them set up and ready to go,” he says. “And I have two different flies on each rod.” The bigger weight sizes of rod allow Cohen to throw bigger patterns, yet still retain enough touch and feel to detect more-subtle bites in tougher conditions. When rigging up the two different rods, he likes to vary his line styles to make sure he can present flies differently and make his fishing setup more efficient. “I’ll have a floating line on one and a sinking or intermediate line on the other, but that also depends on the situation and the day, and the flies I’m fishing,” he says. Even though Cohen fishes waters that are full of big, toothy fish like northern pike, he still uses monofilament leaders rather than a steel leader that a dedicated pike angler would tie on. “If I’m bass fishing with a sinking line, I’ll just go with a straight 3-foot piece of 20-pound Berkeley Trilene monofilament,” he says, “usually with no taper at all.” When he switches to a floating line, he may use a slight taper.

No matter which leader style Cohen chooses, he likes to make his own leaders from different lengths and styles of line—that way his presentation is exactly how he needs it to catch fish in small ponds. “I make them myself and just blood knot my sections together,” he says. “I usually start out with a pretty stiff butt section, because a lot of my topwater flies are pretty big so I like to be able to flip them over.” Keep in mind a ratio that keeps 60 percent of your leader as a heavier butt section, followed by one or two sections of thinner-diameter line leading up to your fly. Cohen says his DIY leaders are perfect for chasing all of his favorite warmwater species, except carp. “When I’m carp fishing, I need them to be 9 feet long, and I want them to be really smooth,” he says. Since carp live in waters with lots of weeds and they can be extremely finicky, making your own leaders can present a problem. “Unless you’re covering your blood knots with something like Knot Sense from Loon Outdoors, blood knots catch weeds, and when you’re carp fishing, catching weeds sucks.”

Having two fly rods that are rigged up and ready to cast also allows Cohen to use his secret weapon when targeting warmwater fish. He likes to call it the “comeback cast.” “A lot of the time these fish will follow, follow, follow, but there’s no commitment to a fly,” he says. “I like to have a second rod at all times so that if I get a fish that won’t commit but is real hot, like following the fly around but not eating it, I can grab that other rod immediately and cast another fly out there that’s significantly different from the first fly.” Casting out a secondary fly that’s completely different from the first will often trigger a reaction from the fish, as it won’t suspect the comeback presentation. If you get a strike on the comeback cast, hang on, as they can be the most violent strikes of the day. “I store rods in the holders that are built into the sides of my Kilroy,” Cohen says. “The active rod that I’m fishing with stays in between my feet, lying on the bow, while the one rigged for the comeback cast will be in the rod holder on my right, ready to grab.”

While Cohen is picky about where he puts his rods, he doesn’t put too much added effort into rigging his boat for his style of fishing. “I really keep my rigging down to a minimum,” he says. “I like to keep the boat free and clear of obstacles or anything that can tangle up my fly line.” The only customizing he has done to his boat is placing a PanFish Portrait camera mount and Dog Bone combo from YakAttack, set up with a GoPro, near the bow. “Other than that, it’s pretty basic,” he says. “I use a Vedavoo boat bag to store all of my fly gear, and that stays up near the bow of the boat for easy access.” Cohen says to keep it simple, as the more things that you stick on the boat, the more likely you are to catch your line and tangle up.

Among all the different types of anglers, fly anglers have a reputation for being snobby or elitist, which is something that Cohen says will cost you fish if you’re not careful. “Fly fishermen can be stuck on themselves and overlook things like bait fishermen,” he says. Cohen says a bait fishermen you might normally walk right past can be the best research or key on any body of water, whether you’ve fished there before or not. “Here’s the difference—most fly anglers I know are catch-and-release, which means we’re out there for sport,” he says. “Bait fishermen are not out there for sport. Nine times out of ten, they’re out there for a meal, which means they’re not screwing around, they’re not hunting for fish. They know where the fish are, and they also know what the fish are eating. A lot of people would benefit on the water if they stopped and said, ‘Hey, how’s it going, how’s the fishing going today, what are you using, are you catching anything?’” Cohen says that quick conversation with an angler on the bank can give you a better starting point than hoping to spot the right school of baitfish as you’re paddling out to your first spot.

Cohen has another warning for fly anglers, who can get stuck in their own heads day after day. “We get stuck in a rut as anglers and we do the same thing over and over again, working the same water, working the same water the same way,” he says. When it comes to smaller ponds, changing tactics and being sensitive to the changing conditions are paramount to hooking up. “Some of these smaller bodies of water, maybe they see a lot of people, or maybe the fish are well fed and you need to try to get a reaction out of them,” Cohen says. “I find a lot of people, because they think they know everything about that water, they’re afraid to change tactics.” If he is stripping a fly in really fast but it’s not yielding any results, he will change tactics, even though that speed may have worked the day before. “I always say that I’ve never fished the same water twice, because things are constantly changing,” he says. “Barometric pressure changes, maybe it rained, maybe something new was introduced to the system, maybe the water temperature changed, maybe there was a hatch—you never know. If you’re not constantly changing what you’re doing and trying to evolve, and trying new tactics on the water, you’re never going to catch fish consistently.”

If there’s one thing Cohen wishes anglers would learn more about when it comes to fly fishing, it’s the science of how fishing works, not how to fish. “Everyone knows that smallmouth bass eat crayfish, but most anglers don’t know how that all works, like what size to use at different times of the year, how often they molt, the fact that when that water hits 50 degrees there’s a brief window in the spring when adult crayfish become available to smallmouth for the first time,” he says. “The biology of crayfish, as it relates to bass fishing, that’s the stuff that I like to know—it makes you a better angler.” Time to start dusting off your old marine biology books from high school.

Cohen has used that better understanding of biology to develop fly pattern after successful fly pattern designed to catch big warm water species all around the world. With creative patterns and even more creative names like ManBearPig, Stank Leg Slider, and One-Eyed Willy Popper, he has created a name for himself and for his company, Super Fly, as one of the most innovative in the industry. Since that first time fishing with him, I’ve been impressed by the action of his flies and his ability to pick apart warmwater fisheries and develop a pattern. We spent hour after hour fishing a lake in Vermont recently, trying for a last-chance bass after a morning spent getting skunked on a nearby river for northern pike. Of all three anglers, Cohen was the only one that day who hooked up, even though we were fishing in super-clear water under bluebird skies in the middle of the day, normally very tough conditions. Tying on a big, flashy deer hair popper, Cohen started picking apart the weed lines until he got the first and only strike of the day. Though his 8-weight fly rod barely bent against the weight of the tiny largemouth bass, sometimes you have to take what you can get.

The question I always get when putting in at a bigger lake or reservoir with my kayak and a fly rod in hand is, “How are you supposed to cover the whole lake with that thing?” The secret is, you’re not.

The great thing about fishing with a fly rod from these little plastic boats is that it makes you slow down and focus on each spot, even each cast, much more than the average angler normally would. I recently paddled up to a fairly large cover in my local lake, a lake that would take me a few days to even just paddle and probably a week or two to fish the whole thing, at the same time a bass boat motored in. After maybe five casts without any luck, the bass boater fired up his outboard and threw up a giant wake that made me want to yell out after him. Since he had the luxury of testing out a bunch of different spots in a day, realistically with the entire lake at his disposal, he could throw a few casts into every corner and find the easiest fish in the pond. For the angler that isn’t interested in catching only the lowest common denominator fish, like me, fly fishing from a kayak is probably more your style. That’s why I ended the day with a worn-out arm from catching so many fish in that one cover that the bass boater just couldn’t handle sticking around in for more than a few casts. Forcing yourself to slow down and focus on fewer spots means you have the luxury of truly fishing that one spot more thoroughly, with more precision, than any other form of fishing. You don’t have to go far to catch lots of fish when you’re fly fishing from a kayak.

When looking at the entire lake and trying to decide where to put in, I use the same thought process as when fishing smaller ponds. The downwind side has a greater chance of holding bait and therefore holding fish, but it can also bring me back to the take-out after a long day of fishing if I’ve paddled into the wind. Hopping from cove to cove is basically the bread-and-butter of fishing in a kayak on larger bodies of water. Since we don’t have the range of a big powerboat, we need to be able to pick apart water more efficiently than other boaters.

When approaching a cove, I initially look for any obvious structure or drop-offs that I should hit first. If there’s nothing glaringly obvious at first glance, I’ll likely check my GPS chart on my fish finder/GPS unit. This way I can make sure that I’m hitting the most likely targets first and then working my way around the rest of the water. Look for drop-offs, edges, or points extending into deeper water that sit directly adjacent to shallow water. Fish will most likely be cruising these lines and ambush points, waiting for bait and forage to be caught by surprise. You can take advantage of their hunting instinct by giving them an easy target, your well-presented fly. If there is obvious structure, though, like weed lines, vegetation, stumps protruding above the water’s surface, or downed trees, fish will likely be orienting themselves close to that structure—again, looking to ambush their prey.

Depending on the time of year and the water temperature, fish may be closer to or farther away from the structure. If the water is cold or it is near the spawn, fish will likely be holding very close to the structure, so making sure your casts land as close to the structure as possible is a good idea. It’s also smart to start farther away from the structure with your first few casts and then work your way in, just in case outliers are patrolling the edges of the structure. This way you have a better chance at catching more fish from within the same piece of water and same piece of structure, rather than catching one fish at the deepest spot in the structure and spooking every other fish around when you set the hook.

If there is no obvious structure at all, or obvious points on the GPS map that are presenting a good ambush point, I will likely work the cove the exact same way I would fish a smaller pond when pond hopping. Start at one end of the cove and beat the bank all the way around until you reach the other side. If you start catching fish, pay attention to where they were in relation to the bank, what depth they were holding at, and how you retrieved your fly. The only difference between decent anglers and great ones is paying special attention to what they are doing when they catch a fish so that they can replicate it exactly over and over again to keep catching fish.

If you’ve completed your bank-beating around the entire cove without a bite or sign of life, start moving into the deeper water, where the cove begins to meet the rest of the lake’s deeper water, and look for fish that are likely suspending or orienting themselves to deeper structure that you won’t be able to see, except for on your fish finder when you’re directly above it. Many anglers fishing from larger boats or boats with motors don’t have the luxury of hitting this secondary water after they’ve beaten the entire bank because their boat creates more draft and has a much more significant presence than a kayak. The added stealth of fishing from a kayak means that you can float directly above the fish while fishing the bank and then after only a few minutes’ rest, go back and fish that same water you just floated over. It’s a good idea when hitting this secondary water to start at the same end of the cove that you started at while beating the bank. This will give the fish more time to forget you were ever there before trying to catch them again. If you still haven’t caught fish while hopping from cove to cove and systematically picking them apart, it may be time for plan B.

When coves and inlets fail, it’s time to look at the last resort but still very effective tactic for the kayak fly angler: trolling. Not only can trolling with a fly rod allow you to cover a lot more water than casting, but it is also one of the deadliest ways to present a fly in front of many more fish. Since a fly is much more realistic and effective than the average lure, keeping your fly at the exact depth the fish are holding at gives you a greater chance at hooking up with fish than your buddies throwing giant crankbaits or jerkbaits.

When choosing a rod that’s better at trolling than casting, a slower-action rod will allow you to present the fly much more subtly and will give you a better chance to set the hook before the fish even knows that it’s hooked. For trolling I tend to choose flies that will pulsate in the water and give off as much action as possible. Flies that are made of bucktail present a great shad imitation, but the most effective material that I like to throw is bunny strips. Strips of bunny will give your well-trolled fly the feeling of coming alive and will impart a much more erratic action than any lure, which fish won’t be able to resist.

A sturdy rod holder that is positioned in a place on your kayak’s deck that still allows you to paddle efficiently means you can maintain the perfect speed and fish at the same time. Mounting the fish finder within reach but also in front of you as you paddle means you can carefully watch the rod tip for a strike and never miss a fish. If you do see a fish strike, paddle a few more strokes extra hard and you’re likely to set the hook without even touching the rod, doubling your chances of landing the fish. Octopus or circle hooks are another smart idea when trolling, and most flies tied on these hooks will work just as well while casting. Another tip, try to choose hooks without barbs, as it makes it easier to release fish unharmed.

While it is possible to troll a fly rod without electronics, a fish finder and GPS combo unit will make your day more productive by leaps and bounds, allowing you to focus on areas that are more likely to produce. When looking at your GPS unit, there are a few areas to focus your trolling efforts. Depending on the time of year and the water temperature, fish could be holding anywhere from 5 to 25 feet, so choosing a path that samples different water depths is a smart idea. Even when deciding a route along a certain depth, it’s a good idea to zigzag as you’re paddling to vary your depth a little, and to also add pauses in your trolling retrieve to entice even more fish.

Once you’ve found the depth fish are holding at, either by catching fish or spotting them on your fish finder, focus your efforts within a few varying feet on either side of that depth. The most productive areas of a lake for trolling are the saddle between two islands or higher spots on the lake bottom, where the bottom will dip between the two high spots, as well as along edges, drop-offs, or underwater structure. Zoom out on your GPS chart and look for high points that extend out into deeper water in a peninsula. You’re looking for areas where fish could be waiting in the deeper water to ambush baitfish and smaller prey that are coming from the shallower water.

Much like the coldwater fisheries that we’ll discuss in the next chapter, big lakes and reservoirs can be seriously tough to pick apart and develop a pattern. One of the most frustrating trips that I have taken in my career as a fishing writer was to a little island in the middle of Lake Michigan. Beaver Island is known far and wide as a haven for fly fishing for carp, as the gin-clear waters that surround the tiny spit of land can make an angler feel like he’s in the Bahamas, not the Great Lakes. Sure enough, as soon as we hit the water in our kayaks, it looked like a postcard from the Caribbean, complete with colorful houses on the shore and giant fish swimming in the shallows. Those fish, of course, were giant carp.

My co-angler for the trip was Kayak Fish the Great Lakes founder and Michigan native Chris LeMessurier. LeMessurier spends nearly the entire year fishing these inland oceans for fish that would make your knees weak, everything from trophy smallmouth and largemouth bass to behemoth king salmon. I thought having a Midwest native show me around Beaver Island would give me just the right amount of fishing mojo needed to hook up with the most stuck-up and skittish fish I’ve ever encountered. Carp are also known as the golden ghost or poor man’s bonefish, so I knew going into the trip, a three-day weekend of fishing from sunrise to sunset, was going to be long and especially frustrating. What I didn’t know was that it’d also be one of the few trips of the year that I was skunked on—or at least almost skunked.

Instead of fishing the entire lake from a kayak, which would have been entirely useless without days of research, planning, and scouting, LeMessurier and I focused on the coves and points that we could target and pick apart more effectively in one long weekend. It didn’t help that neither he nor I had never fished for carp at that point and had literally no clue as to how to catch one. Tying on the buggiest, bushiest nymph patterns we could find in our tackle boxes, we each tried our own version of flats fishing that we were used to, LeMessurier with a background in fishing Lake St. Clair for smallmouth bass, and me fishing the white sand flats of Cape Cod for striped bass. In case you didn’t know, bass and striper tactics do not work on carp—at all. Refusal after refusal sent us both screaming and cursing into the heavy winds that would crop up in the early morning. Instead of leaving our flies completely motionless and letting the carp investigate them on their own time, and then deciding to eat, we would twitch, skitter, strip, or pulse our flies constantly, trying to entice a bite. If carp were as aggressive as bass and stripers, that would have been one of the coolest trips of my life, like something out of a fishing movie. Luckily, though, there was a backup plan that made sure we ended every day with our hands smelling like fish, not shame.

Had LeMessurier been fishing a new lake system back home, not on a spur-of-the-moment trip with me, he would have spent a few days dissecting the water and gathering intel to decide where to launch and how to fish the lake. “When you’re dissecting a new lake to fish in a kayak, you have to be more efficient,” he says. “You can’t just run across the lake to fish one spot and if it sucks run all the way back, 5 miles across the lake.” Being able to dissect that water and break it into smaller, more manageable chunks also helps when you’re casting with a fly rod. LeMessurier says, “You have to be efficient on how you use your energy when you’re casting—you don’t want to be making pointless, inefficient casts.” He puts most of his thought on where he suspects the fish will be orienting on the new lake—that way when he launches his kayak he can launch close to where the fish will be, maximizing his time actually fishing, not paddling around. “Focus on structure and what the pattern might be,” he says, “then position yourself as best as possible. You have to be more specific about where you put in compared to fishing from a motorboat.”

When you’ve picked the right spot to launch and can get on the fish faster, your whole day becomes easier. Not only is it easier to find fish, but it’s also easier to start developing the pattern, which LeMessurier says is the most important step to catching fish on a big lake. “You take the big picture and then you step it down,” he says. “You think about the seasonal pattern: What are the fish doing? Is it a spawning thing, pre-spawn thing, or post-spawn thing? Is it a summer thing? Then you break it down again to their feeding habits and how they’re going to be looking for forage, and then again down to what specifically those fish are going to want.”

Choosing a fly based on this principle is less about what fly and more about what kind of fly you’re going to be throwing. Instead of saying I want this fly or that fly, you’re thinking about this style of fly or that one. “Ask yourself, are fish likely to chase their forage right now or should I pick a fly that can be fished still?” says LeMessurier. No matter how confident an angler is in the fly choice, no matter what, it’s all a guess. “You aren’t a fish, you can’t read their minds, you can’t ask them, so you’re taking a guess at it, but its an experiment,” he says. “Listen to the fish and let them tell you what’s working and what’s not working, and readjust.” If you find that fish are refusing your fly or having a negative reaction to it, it’s time to change. What that change is depends on the reaction, but LeMessurier says it could be something like, “Maybe it’s a smaller fly, maybe it’s a color change. Be conscious of what you’re throwing and what you’re doing so you can tell what fish are reacting to and know what needs to change first.”

If you’re not sure where to start fishing first or where to put in your kayak, LeMessurier says to look where structure changes. “I like bass and pike, fish that I can get a lot of action on, so I like casting and stripping versus drifting or slow-sinking presentations,” he says. “I look for structure that those type of fish are going to focus on, like rocks and weeds.” Since he prefers shallow water, he’s also looking for depth changes, especially those that coincide with structure changes. “I’m either in lily pads/weeds type of structure combined with shallow water to deep-water or deep water with big drop-offs,” he says. “The weeds that provide ambush points on those drop-offs, that’s what I’m looking for. A weed line on a drop-off from 2 feet to 10 feet, that’s where I feel I have the best shots at fish.”

Positioning yourself along that structure change is important so you don’t spook fish that are cruising around and looking for bait. “Close but not too close,” LeMessurier says. “That weed line, for example, I like to be upwind of it, on anchor, but using an anchor trolley to position my boat either parallel or perpendicular to the wind.” He says that positioning your boat properly can help with making sure your presentation is up to par. If the bow is pointed at the structure, for example, “I can stand up and get a much better cast versus trying to make a cast in a sitting position,” he says. If the wind is a little stronger and standing up isn’t a good option, LeMessurier will position his boat perpendicular to the wind using the anchor trolley and will sit sidesaddle, dangling his legs in the water. “That way I’m in a semi-sitting position,” he says. “You can really extend your back and arms, so I can use better technique that way than sitting in the chair with my knees bent.” That sidesaddle position will also aid in line management, usually the trickiest part about fly fishing from a kayak. “Then all of my line is in my lap or in the water where my knees are and it’s a much cleaner way to have your stripped line or slack line kind of sitting in front of you,” he says.

Since LeMessurier spends most of his time chasing bass and pike, fish that both require different tools to chase them, he wants a rod and line combination that is versatile over precise. “Typically that’s a 5- to 7-weight,” he says, “and I prefer a sink tip because I tend to do more streamers and moving baits, like cray-fish patterns, which require a strip retrieve.” The sinking line allows LeMessurier to work his flies a little bit faster, since they sink faster. Though he fishes topwater occasionally, with frog or hopper patterns on floating line, he says a sinking line is the more versatile of the two. “If it’s not sinking, it’s not doing much. You have to wait, and I’m not a patient person,” he says. “That sink tip lets me strip it up a little quicker and let it sink back down faster; it works that water column a little better. Especially when working a streamer, that sinking line makes the presentation more consistent, since I don’t have to wait for it to recover and sink back into position in the water column before I strip again.”

It’s that consistency that many bass and pike anglers rely on to fool fish into striking. A bass or pike will track a baitfish’s movement and, like a quarterback leading a receiver, plan its striking route accordingly in order to intercept its prey. As for line style, LeMessurier wants that sinking line to be weight-forward—that way he can throw those bigger, hairy streamers that big bass and pike love to hit. When it comes to bass and pike, he falls into the camp that believes the fish are “too dumb to care” about leaders. That means he’s not using the stealthiest choice of leader because he doesn’t have to; instead, he goes for strength. “Most of the time I’m running a fluorocarbon leader, probably 7 to 9 feet long, and probably in the 8-pound up to 12-pound strength range,” he says. “Sometimes I’ll tie 12 or 16 inches of steel tippet onto my leader, just to make it more cut-resistant for the pike.”

Even though LeMessurier spends a lot of time on the water, he doesn’t believe in dropping serious money on a fly rod when there are many rods available at a much cheaper price that will still do the job. “I like a moderate to fast, something forgiving,” he says. “I don’t have a real pure cast, so I want something a little more forgiving.” Rods in the $100 to $120 range are his favorite, he says, “something smooth enough that I can cast pretty far and is inexpensive in the world of fly rods. There are a lot of really good rods for really good prices.” LeMessurier cautions would-be fly anglers to stay away from the budget combinations, though, so don’t go looking in the bargain bin for the cheapest rod you can find. Instead, look for the best rod for the best price. “I don’t believe in cheap—I think you have to have some quality to it,” he says. Above all, try casting the rod before you buy it, or at least inspect the components and overall quality to make sure you’re not spending money on a cheap rod that will break quickly, especially on a big fish.

While saltwater anglers will swear by a big reel, LeMessurier and many other freshwater anglers think of reels as mostly a line holder. “A large-arbor but inexpensive reel is a good choice, because for most of the fishing I’m doing, I’m retrieving them on the strip,” he says. “Every once in a while I’ll get them on the reel and fight them that way, but I’m not getting into anything that’s taking me into my backing like a musky, a big trout, or saltwater gamefish.” For carp, though, a good reel is a better choice, since you’re fishing with leaders that are a little finer and stealthier. A good drag system will keep those lighter leaders intact while still letting you put a lot of pressure on the fish, meaning you might actually have a chance at landing it.

“Less is more . . . I know it’s cliché, but I have very few accessories on my kayak when I’m setting up for fly fishing,” says LeMessurier. “This approach allows me to keep a snag-free surface and be more productive when casting, fighting, and landing fish.” His garage is full of kayaks, rods, reels, and rigging projects, as he’s a conventional angler as often as a fly angler, but his kayak crate is the center of all his rigging customizations. “My customized milk crate is an invaluable piece of equipment on my kayak and has been perfected over the past ten years,” he says. “Much more than a box to hold stuff, my crate helps me organize tackle, camera equipment, safety equipment, and much more.”

As for LeMessurier’s rod storage strategy, it’s all about avoiding snags on the backcast. “I keep extra rods taken apart, in their cases, stored inside the kayak hull,” he says. “I keep just one rod ‘at the ready’ and that simply lies on my lap while I’m padding.” For fly storage, he looks for fly boxes that are big enough to hold giant, fluffy streamers—the bigger the better. “To be honest, I have yet to find a fly box that is too big,” he says. “When that’s not in use, I store it behind me in the crate.” Most importantly, LeMessurier stresses being mindful when rigging your kayak—that way you won’t waste time setting things up that you won’t use on the water or won’t help you catch more fish. “Be mindful of what you have on and around your deck/cockpit,” he says. “If you simplify your approach, there will be less opportunity for problems and you will be able to focus on the fly fishing itself.”

Every time our game plan on the flats of Beaver Island failed, LeMessurier and I would pack all of our gear back into my truck, hit the dusty dirt roads of the island, and drive into its center. At the heart of the island was a cluster of smaller ponds that were full of largemouth bass and northern pike. Tying on a spinnerbait triggered bite after bite, starting with our very first casts, which let us rest easy each night, smelling like fish. Having that backup plan allowed us to be more experimental with our tactics on the flats fishing for carp, which, even though it didn’t end up getting us any fish, did allow me to learn more than I’ve ever learned on a single trip. Knowing that you can catch fish later lets you put more focus and effort into your plan A, which without the right knowledge and a few tips from pros who actually know more about the fish you’re targeting, might not be a very good plan.

Some of the most productive days of my entire life have been fishing warmwater rivers. Since the spots where fish are holding can be more predictable than when fishing ponds or lakes, hooking up with a fish is just a matter of finding the right mixture of water flow and structure. Regardless of the species, fish—and really all animals—look for the same thing: the most calories for the least amount of work. If a fish can get a big mouthful of food by moving as little as possible, it has a greater chance at survival, because the number of calories it’s gathered is greater than the number of calories it’s burned that day. Anglers can take advantage of this when fishing rivers, whether for coldwater species or warmwater, by targeting the most likely spots that fish can find food without moving around too much.

A precaution you should take before putting in on your local river is what guides and whitewater paddlers call “rigging to flip.” This philosophy reasons that there’s a good chance you will eventually flip your boat, and will most likely flip it without any warning or time to hold down your gear, so you should tie down or attach lanyards to any gear that doesn’t float. While anglers can get carried away with tying down their gear, strapping everything down to the point that it is getting in their way of paddling, fishing, or worse, getting back into their boat after they’ve flipped, you should still tie down the gear that will be costly to lose or won’t float. Many gear lanyards on the market attach via quick-release clips to your boat and gear and are designed to break away or quickly detach in the case of an emergency. These gear lanyards will also allow you to use your gear as freely as if there were no lanyard attached, as they are usually designed to be stretchy or made from bungee material and will move with you. If you’re looking to spend as little money as possible, though, you can rig up your own gear lanyards by visiting a local hardware store and finding either paracord, a thin, strong rope rated for high strength tolerances, or thin bungee that you can then tie to your gear and your kayak.

Now that you’re safe to hit the water and prepared for all the challenges that fishing moving water can present, it’s time to find the fish. Understanding how water flows around objects in the river will help you determine where fish will likely be hiding and where to place your cast.

When water is flowing downriver and meets a rock, the water has no place to go but around it. If the rock is deep enough in the river and surrounded by water on all sides, the water will flow all around the rock except for directly behind it. Imagine walking through a city on a windy day. If you hide behind a bus, you’ll find yourself in a wind-free zone, surrounded by the wind moving around the bus. Water flowing downriver acts in the same way, unable to push water on the downstream side of the rock, creating a pocket of neutral water. These are also called eddies when the rock is large enough or breaks the surface of the water. You can easily identify an eddy in the center of a river by looking for a triangle of swirling water extending out from a rock at the water’s surface and moving downstream.

Not only do eddies provide a safe harbor for your boat to rest in the current without the need to paddle to maintain your position, but they also create a safe harbor for fish. Since fish survive by expending as little energy as possible, they will wait along the seams of the eddy and watch for forage to pass by in the current. These seams are usually the most productive places to cast your fly when river fishing, as the fish will be watching those exact spots. It’s also possible that the bigger fish will be directly behind the rock, as deep into the slack water as they can possibly swim, so placing a few casts around the slack water gives you a good chance to hook up.

When fishing in rivers, locating and targeting these seams and eddies will usually reap the greatest number of fish. These current seams will often yield fish regardless of the fly you choose, though the most exciting is by far a topwater popper or slider pattern, especially for warmwater species. If the water is too cold and the fish are too lethargic to chase bait on the surface, these topwater flies are going to lose their potency. When this happens, a weighted streamer will allow you to probe the deeper eddies where fish will be hiding out and waiting for the warmer weather. If fish are still not reacting to your fly, or reacting negatively, downsizing your fly and switching to something with a more natural presentation will increase your chances of hooking up. As a last resort, switching to a subtle wet fly pattern can fool even the toughest fish, usually salvaging an otherwise fishless day.

When the river’s water temperature reaches higher levels, fish will seek the cooler, more aerated riffles to wait out the warm spells. When water flows over rocks, it creates turbulence and the water will froth and foam, what paddlers call whitewater when it reaches high enough water levels. Even if the water is at low levels, the subtle rippling and turbulence adds greater levels of oxygen to the water’s chemistry and creates a better habitat for fish to rest. These oxygen-rich havens are also cooler because the air has lowered the temperature of the water. When the water reaches above 70 degrees, this is usually where I focus my efforts, as the deeper pools and eddies will tend to be too warm for fish to survive for very long. This riffling water also provides fish with more protection from predation, as the water’s broken surface will better hide and distort their shadows, creating a form of camouflage. When fishing these riffles, I tend to switch to more visible and bigger dry flies that will be seen in the broken water but still rest on the water’s surface throughout the drift. My all-time favorite riffle pattern is a size 8 Stimulator, which features flashes of orange on an otherwise naturally colored fly and tends to be very effective for a wide range of species.

Obvious eddies behind rocks that are poking out of the water and riffles aren’t the only spots where fish may be hiding in the river. Even something as minor as a small boulder on the bottom of the riverbed will create a little eddy for fish to rest in the middle of the current, and a slight depression in the river bottom can create a haven for fish to hide as long as it is big enough for the fish to fit. After targeting the obvious eddies, I’ll throw a few casts into the main current as well, especially if the river is not moving quickly, as these smaller, secondary holes where fish can hide might be right in front of you and you’d never know it without throwing a few casts out there. Current deflecting off an object or a protrusion in the bank can also create a seam where fish can rest and wait for passing food. Bubbles on the water’s surface or swirling current will tip you off that there is calmer water directly adjacent to the current and you should focus your efforts there.

River bends act very similarly to an eddy, creating pocket water that fish can lie in and wait for passing food to drift by for an easy meal. When water comes around a bend in the river, the momentum of the current pushes the water to the outside bank, causing a pocket of calmer water to accumulate on the inside bend of the river. Fish can use this slack water to hide in the same manner they would hide in an eddy, right along the current seams, waiting for passing forage or baitfish. A river bend also creates a secondary holding position for fish, and usually the biggest fish are hiding in this secondary abode. Where the momentum of the river current drives water into the far bank, the force of the water over time will create a cutbank, or in other words, the water will eventually eat away a trench in the river bank to create a hole where bigger fish can hide and wait for the most substantial meals to arrive. Swinging a large and meaty-looking streamer, with a little flash in the pattern to make the fly stand out better in the darker shade of the cutbank, will usually yield the biggest fish of the day, should a fish be present in the undercut bank at the time of your cast. To properly swing your fly, cast out into the current, upstream of your boat’s position, and let the current take control of your fly’s speed and direction. The fly will swing out and around, towards the opposite bank and straight into the probable lair of a big fish, therefore completing a realistic presentation of a large baitfish getting caught in the current and flushed into its waiting jaws.

One of the best days that I’ve had on the water when fishing warmwater rivers was also one of the toughest. I was fishing with Kayak Fish PA guide Juan Veruete on the famous Susquehanna and Juniata Rivers, both known far and wide as fisheries that hold behemoth small-mouth bass. The week before I visited, Juan had been telling me about the hundred-plus-fish days he had been experiencing, all high-caliber, trophy-size fish. Then the day before I arrived, a massive cold front had rolled in, bringing near-freezing temps and even snow flurries, causing the water temperature to drop a whole 10 degrees. When the temperature drops that quickly over a short period of time, it makes the bite almost nonexistent. In order to hook up, we had to pull out all the stops and switch to winter fishing tactics, even though it had been full-blown spring only a few days before. Having a guide with vast knowledge of the river’s structures and patterns was the only reason we were able to catch fish during my trip.

According to Veruete, knowing where the fish are and the structure they like is the most important part of fishing warmwater rivers. “When I think of a new river, I prepare for the fish first, the target species I’m after,” he says. “In most cases for me that’s river small-mouth bass, so I’m thinking about the forage that’s in that river.” Even when fishing new rivers that he’s never been to, Veruete tries to get the inside scoop on the structure through copious amounts of research before getting his boat wet. “One of the best things to do is find out what forage is in the water and then try to mimic that,” he says. “I’ll look on fish commission websites, biology reports of what’s in the water, and even on social media looking at fishing reports or to find local anglers, all to find out what the local forage is like and what the fish feed on.”

After finding out what the fish are looking to eat, it’s a matter of finding the fish. All it takes to find the fish is discovering where they like to hide. Veruete looks on Google Earth or online topography maps of the river and tries to find the best places for fish to hide. “I try to identify the primary theme or structure of the river,” he says. “Every river is a little bit different; some rivers are heavily laden with wood, like rivers down south in Alabama. That’s a major piece of structure that fish will relate to and orient themselves on.” Since all rivers are different, it’s not about finding any structure, but the right structure. “When I’m fishing the Susquehanna, there are a lot of ledges and that is the major piece of structure that is in that water,” he says. “That’s something that the fish hold on or use to feed and live in those areas better. Once I find out what the major structure is on the river, I try to think about how the fish relate to that.”

Veruete has used this technique for rivers across the country and has perfected the tactic to the point of winning tournaments on new pieces of water that he had never fished until the day of the tournament. When it comes to smallmouth bass on his local river, the Susquehanna, he has them down to a precise pattern. “Here on the Susquehanna, if there’s a piece of wood in the water, which is rare compared to other structure, it’s going to hold fish, but not as good as a piece of submerged ledge rock or ledge system,” he says. “That wood is going to hold fish, but it’s not going to be a constant producer. So when looking at fishing a new river, I’m trying to figure out what the primary structure is on that river, what the topography is on that river, and try to hone in on some of the key features of the river that I can use to focus in on the fish.”

Besides finding out the forage and the primary structure patterns, you still have to know where to fish along the river, which in some cases can run for miles and miles, even across multiple states. Veruete will look at those topographic maps once again and tends to target bends in the river where fish are likely to stack up. “If a river has a lot of bends and switchbacks, you can look on a topographic map and see where the lines are the closest together,” he says. “Focus on the sections of river with those steeper areas, because a lot of times, especially in a mountainous area, that means there is a lot of slab rock and big boulder rock that has fallen off the mountain.”

Remember, though, that a good angler will always have to adapt to what they see on the water, no matter how good your research is. “There are always things that surprise you when you go someplace, and you kind of just have to go with the flow,” Veruete says. “You might get on the water and see that the fish for whatever reason are relating to deep cuts in the gravel in the river and that’s something that you couldn’t really know looking from afar, so you’ve got to adjust to some things once you get on the water.”

Once you put in on the river, it comes down to checking your research and finding out how accurate all your hard work was. When you get to the structure that you believe is most likely to hold fish, selecting the fly pattern to throw is more about the depth than the color. “You want to get something that looks close to what is in the river, but a bass is not a crappie,” Veruete says. “When crappie fishing, if you have a yellow jig and you’re not catching, your buddy with a purple jig might still be catching—they really key in on color. With bass, as long as you’re in the neighborhood with the right shape, something that looks familiar to them, you’ll be good.”

Veruete says color is still important, but what matters most is finding the right depth and how you move that bait through the water. Pick a variety of flies that will let you cover the entire water column systematically. Veruete tends to work from the bottom of the water column up to the top in the winter or cold-water months, and then from top to bottom in the water column during the warmer months. “I cover the top of the water column with topwater poppers, the middle of the water column with streamers, and the bottom with something like a crawfish imitation,” he says. When in doubt, though, a streamer can be deadly on smallmouth bass because they are so versatile and can be worked at any depth along the water column. “You can work streamers higher, middle, or low, even adding lead weight to the fly to get down to the bottom of the river,” Veruete says. “What I do is systematically try to figure out where in the water column I can get bit, on a certain piece of structure, and that’ll help me start to put the different pieces of the puzzle together.”

While many anglers will stick to the one part of the water column where they first get bit, Veruete suggests experimenting with different depths to make sure you’re covering the most productive water. You may be hooking up with a few fish in the center of the water column, but there might be more fish, and more big fish, on the bottom of the water column that you’re missing. In order to make sure you’re capitalizing on all your research, experiment by testing different parts of the water column as often as you can. “I like to discipline myself, and if I just caught three fish in the center of the water column, I say let me try fishing the bottom and see if I can start catching more or better fish closer to the bottom,” he says. “On my mental clock, if I’m fishing something for thirty minutes and nothing’s happened, I’m going to start looking for something else to do.” Veruete says to make sure you are fishing systematically, working your way down through the water column to the bottom and then working your way back up to the top, to make sure you’re in the most productive zone at any given time.

Don’t get caught up trying to choose the right fly, but instead focus on finding the fish first and then tweaking and perfecting your choice in presentation until you’ve figured out the pattern. “I tell my students all the time that on any given day there are going to be numerous different baits that can produce fish for you,” Veruete says. “Some days are really tough and there is a slim number of baits that are going to work, but on most days you can catch fish on a lot of baits. The key is locating the fish.” Once you’ve located the fish’s primary structure on any given river, the next step is finding out “how they prefer that bait in relation to the structure in the current and what depth they want,” he says. When you can find the fish, you can usually catch the fish.

Just like choosing the right fly to put in the right section of the water column, the same goes for choosing the right fly rod, reel, and line setup. “I want to use the gear that’s going to put my presentation where I believe the fish are,” Veruete says. “I keep it pretty simple if I can. I’ll use floating line, because you can usually work a good part of the water column with floating line, but I also always keep an intermediate sinking line with me because I don’t fish a lot of deep rivers. The deepest I probably caught fish this year was 8 to 10 feet.” Any deeper and you might want to choose a full-sinking line that can get down to the bottom of the water column faster. “Most of the time I’ll fish with a 10-pound-test fluorocarbon leader, because I’m fishing for big 4- or 5-pound fish and using weighted flies like a Clouser Minnow.” Fishing heavy flies and weighted patterns isn’t delicate, so Veruete tends to stay away from tapered leaders altogether, where the leader gets smaller and smaller the closer it gets to the fly. “Because the flies are heavy enough and I’m not trying to lay them out, I use a straight fluorocarbon leader, whatever I can get. There are very few situations where I’m using a tapered leader.” You can also use a shorter leader when fishing for warmwater bass, as they are going to be less skittish of your line than a coldwater species like trout or salmon. “When you’re fishing for smallmouth, a 5-foot leader is probably going to be enough,” says Veruete. “Plus, it makes it a lot easier to have control of your presentation and your cast.”

One of the most tricky and sometimes dangerous things about fishing in moving water is anchoring. Without the right system, anchoring in moving water can cause your boat to flip you into the water or drag your kayak under the surface and prevent you from unhooking from the anchor in time. Veruete says a stakeout pole is a much better solution, especially when fishing shallow warmwater rivers, since it can be quickly and easily deployed and pulled up to keep you safe and secure on the water. “A stakeout pole through your scupper or a more advanced system like a Power-Pole Micro Anchor is much better than an anchor,” he says. “The anchors I’ve tried just seem too unwieldy. A lot of times you’re trying to swing flies, so having a stakeout pole at the back of your boat where it’s not going to get in the way is actually pretty awesome.”

Having a system like a Power-Pole Micro Anchor that can be mounted to the back of your kayak will also allow you more room for fishing. When you have an anchor, you have to account for two things: enough line, usually twice the amount of line than the depth you’re fishing at, and an anchor trolley system. An anchor trolley system allows you to adjust the contact point of your anchor line to your boat, using pulleys to move the line along your kayak. Using an anchor trolley in a river, for example, you can move the contact point of your anchor line to the stern of the kayak, pointing your boat downstream. If you move the contact point all the way up the front of the boat, you’d be pointing upstream but still anchored in the current. This allows you to keep facing the direction you want to fish. It’s also a good idea to keep your anchor trolley system set up so that you’re never sideways in the current.

“The more gear that you have attached to your kayak, the more your line will get hung on those attachments,” Veruete says. “I clear everything off the bow deck and out of the cockpit of my kayak, including my tools.” Any electronics or accessories forward of Veruete’s seat are taken off and relocated behind him, so that the deck of his kayak can be as low-profile as possible. This logic even extends down to each nut and bolt placed on the kayak at the factory. “If there is any hardware in the kayak’s cockpit that can create a potential catch point for fly line,” he says, “a quick way to solve the problem is to take a piece of masking tape and tape over the hardware. It’s quick and requires no modification of your kayak hardware.” Even the foot pegs in the kayak’s cockpit are pushed as far forward as possible—that way line can collect freely at Veruete’s feet as he is stripping instead of becoming tangled up.

To make sure rods are out of his way, Veruete attached a RAM fly rod holder to the kayak’s hull, behind his seat, with a low-profile Mighty Mount by YakAttack. “I angle the rod straight off the back of the kayak and parallel to the deck, reducing the chance of entanglement on a backcast,” he says. “Rods I’m not using remain in their tubes inside the kayak, and the rod that I’m currently fishing with lies on the deck in front of me.” Veruete uses an Orvis Safe Passage hip pack, with an optional tippet bar, to store his fly boxes, forceps, line clippers, and other essentials. “It’s perfect for the lawnchair-style seat in my Wilderness Systems ATAK 140,” he says. “I attach the hip pack to the back of the seat, which keeps my flies and tools out of the way but also in easy reach.”

One piece of gear that’s harder to keep out of the way, but also completely indispensible to Veruete’s style of fly fishing, is his YakAttack Little Stick. “It’s a short stakeout pole that you can use in shallow rivers to pin your kayak in place,” he says. “I deploy the Little Stick when I’m in shallow slower-moving water through my forward scupper. It finds a crack in the rock and holds the kayak in place.” The ability to pin his kayak in place in the river’s current makes it easier for Veruete to present his flies exactly how he needs to in order to catch more fish. “It makes it easier to swing flies across the current and target fish without worrying about where my kayak is headed on the river,” he says. “If you’re a do-it-yourself kind of kayak angler, you can make a short stakeout pole by cutting a wooden rake handle or broom handle to the length of 3 or 3 1⁄2 feet. That’s about the perfect length for this application.”

When I was fishing with Juan in the early spring temps, my fingers and toes were just barely registering any feeling, about the same subtlety that the big Susquehanna River smallmouth bass were using when they hit our presentations. Juan had us focus on anchoring in the eddy of two big rivers, where the Juniata and the Susquehanna combine, allowing the best chance at the most fish. With a swinging presentation we were able to pick off fish, something no one else on the water seemed to be able to do, at least within sight, from smaller fish to true Susquehanna River trophies. Without Juan’s knowledge of the right structure and presentations that would work in the warmwater rivers near his home, there is no way I would have been able to hook up that day. I especially would have never caught my personal-best record small-mouth bass, which still stands today.