and it was said that he mapped the little stars

of the Wain,314 by which the Phoenicians sail.

According to some he wrote only two works, On the Solstice and On the Equinox,315 since he believed that everything else was incomprehensible. According to some he seems to have been the first to pursue astronomy and to have predicted solar eclipses and solstices, as Eudemus states (Th 46) in his History of Astronomy.316 This is why both Xenophanes (Th 7) and Herodotus (Th 10) admire him. Both Heraclitus (Th 8) and Democritus (Th 15) testify to this. [24] Some, including the poet Choerilus (Th 9), say that he was also the first to say that souls are immortal. He was also the first to discover the sun’s path from solstice to solstice, and, according to some, the first to declare that the size of the sun is one seven hundred and twentieth of the solar orbit and the size of the moon is one seven hundred and twentieth of the lunar orbit.317 He was also the first to call the last day of the month the thirtieth,318 and the first to discuss nature, as some say.

Aristotle (Th 31) and Hippias (Th 16) say319 that he attributes souls even to inanimate things, instancing the magnet and amber320 as evidence. Pamphile (Th 102) declares that he learned geometry from the Egyptians and was the first to inscribe a right triangle in a circle, and that he sacrificed an ox. [25] (But others, including Apollodorus the calculator321 [cf. Diog. Laert. 8.12] [claim] that Pythagoras [was the one who discovered this].322 For he was the one who advanced furthest what Callimachus says in his Iambics that Euphorbus the Phrygian323 discovered, “scalenes and triangles” and everything else that belongs to the study of lines. He is thought to have given the best advice in political matters as well. At least, when Croesus approached the Milesians for an alliance, he prevented it, which saved the city when Cyrus defeated him [Croesus].

Clytus (Th 35) says, as Heraclides reports (Th 26), that he became a solitary recluse. [26] But some say that he married and had a son, Cybisthus, while others say that he remained unmarried and adopted his sister’s son. When he was asked why he did not have children, he said “Because of my love for children.” And they say that when his mother tried to force him to marry, he said “It’s not yet the right time,” and later, when she persisted after he had become old, he said “It’s no longer the right time” (cf. Th 129; Th 368; Th 512; Th 564 [318]). In the second book of his Miscellaneous Notes (Th 60) Hieronymus of Rhodes also says that he wished to show that it is easy to be wealthy: when there was going to be a bumper crop of olives he realized it in advance, rented the olive presses and made a huge amount of money. [27] He posited water as the principle of all things and that the cosmos is animate and full of daimons. They say that he discovered the seasons of the year324 and that he divided it into three hundred and sixty-five days.

He had no teacher except that he went to Egypt and spent time with the priests. Hieronymus (Th 61) says that he measured the pyramids by their shadow, measuring it when [our shadows] have the same length as we do.325 He was the companion of Thrasybulus, the tyrant of Miletus, according to what Minyes326 says (Th 566).

The story is well known about the tripod that was found by fishermen and sent by the people of Miletus to the Sages. [28] They say that some young men of Ionia paid some Milesian fishermen for what they would catch. When the tripod was pulled up, there arose a dispute, until the Milesians sent to Delphi and the god gave the following oracle.

Offspring of Miletus, you are asking Phoebus about a tripod?

Who is first of all in wisdom? I proclaim the tripod to be his.

So they gave it to Thales, and he gave it to another Sage, as did one after the other until it came to Solon. He declared that the god is first in wisdom and sent it off to Delphi. Callimachus reports it differently in his Iambics (Pf. 191.32), having got [his version] from Leandrius of Miletus (Th 51): on his death a certain Bathycles of Arcadia left a bowl with the instruction “to give it to the worthiest of the Sages”. It was given to Thales and after making the circuit came back again to Thales. [29] He sent it to Didymean Apollo and according to Callimachus (Th 52) said as follows:

To the one who rules the people of Neileus, Thales presents me, this prize of excellence which he twice received.

In prose it goes like this: “Thales of Miletus, the son of Examyas, [dedicates this] to Delphinian327 Apollo after twice receiving it as a prize from the Greeks.” The one who carried the bowl around was the son of Bathycles, named Thyrion, as Eleusis says in his work On Achilles [FGrHist. I 296 F1] and Alexon of Myndos in the ninth book of his Myths [FGrHist I 189 F1].

Eudoxus of Cnidus (Th 25) and Euanthes of Miletus (Th 565) declare that one of Croesus’s friends took a golden cup from the king to give to the wisest of the Greeks and he gave it to Thales. [30] It went around to Chilon, who asked the Pythian [god] who was wiser than he, and he answered Myson, of whom I will speak. (Eudoxus and his associates list him in place of Cleobulus, whereas Plato lists him instead of Periander [Prot. 343a].) The Pythian proclaimed the following oracle about him [cf. Diod. 9.6].

A man of Oeta, I declare, Myson, born in Chen, is better furnished than you with wise understanding.

The one who asked was Anacharsis. But Daemachus of Plataea [FGrHist 2 A 16 F6] and Clearchus [Wehrli Bd. 3, Fr. 70] say that the bowl was sent by Croesus to Pittacus and then was brought around [to the Sages].

In the Tripod [FHG II 347.2] Andron says that the Argives offered a tripod as a prize for excellence for the wisest of the Greeks. Aristodemus of Sparta was awarded it, but he yielded it to Chilon. [31] Alcaeus too mentions Aristodemus as follows [Lobel-Page Fr. 360]:

They say that once upon a time Aristodemus spoke in Sparta a word that was not reckless:

money is the man, a poor man is never noble.

Some say that a boat loaded with cargo was sent by Periander to Thrasybulus the tyrant of Miletus. It was shipwrecked in the sea near Cos and afterwards the tripod was found by some fisherman. But Phanodicus says it was found in the sea near Athens and after being brought to the city and an assembly was held it was sent to Bias [FGrHist. III B 291 F4a]. Why it was, I will say in my treatment of Bias. [32] Others declare that it was the work of Hephaestus and that it was given by the god to Pelops at his wedding. Then it passed to Menelaus, and was carried off by Alexander along with Helen.

It was thrown into the sea near Cos by the Laconian woman, who said that it would be a cause of strife. Later, when some people from Lebedos bought a netful of fish, the tripod was caught in it, and after quarreling with the fishermen about who it should belong to, they returned as far as Cos, and since they were making no progress they informed the Milesians about the case since Miletus was their mother city. But when the envoys they sent [to Cos] were disregarded, [the Milesians] went to war on the Coans. After heavy losses on both sides, an oracle was delivered that they should give the tripod to the wisest. Both sides agreed to give it to Thales. After it made the circuit [of the Sages] he dedicated it to Didymean Apollo. [33] The oracle proclaimed to the Coans was as follows [Diod. 9.3.2]:

Strife between the Meropes328 and the Ionians will not cease

until you send the golden tripod, which Hephaestus cast into the

sea,

out of your city and it arrives at the house of a man

who in his wisdom knows things present, future, and past.

The oracle proclaimed to the Milesians [Diod. 9.3.2] was:

Offspring of Miletus, you are asking Phoebus about a tripod? and so on as was said above. So much for this.

In his Lives (Th 58) Hermippus refers to him [Thales] the story that some tell about Socrates. He329 used to say that he was grateful to Fortune for these three things: “First, that I was born a human and not an animal; second, that I was born330 a man and not a woman; and third, that I was born331 a Greek and not a foreigner (cf. Th. 563).” [34] It is said that he was being led out of his house by an old woman to study the stars and fell into a trench, and that when he cried out the old woman said to him “Thales, since you can’t see what is underfoot, do you think that you will know about what is in the sky?” Timon too knows that he practiced astronomy and in his Silloi praises him, saying (Th 53):

Thales, the sage astronomical wonder of the Seven Sages.

Lobon of Argos says that his writings take up two hundred verses. The following is inscribed on his statue (Th 55):

Ionian Miletus raised this man Thales and revealed him

as an astronomer senior to all in wisdom.

[35] The following are some of his sayings [Bergk iii. 200]332

By no means do many words make an opinion sensible.

Search for only one wisdom,

Cherish only one thing –

for you will unloose the endlessly talking tongues

of chattering men.

The following sayings too are attributed to him.333

The oldest of existing things is god, for he is unbegotten.

The most beautiful thing is the cosmos, for it is the creation of

god.

The largest thing is place, for it contains all things.

The swiftest thing is intelligence, for it quickly moves through

everything.

The strongest thing is necessity, for it rules all things.

The wisest thing is time, for it finds out everything (cf. Th 564

[320a–f]).

He said that death is no different from being alive. “Then,” said someone, “why don’t you die?” “Because,” he said, “it makes no difference.” [36] To someone who asked which came into being first, night or day, he said “Night – one day earlier.” Someone asked him if a man could do wrong without the gods knowing. He answered, “Not even if he is only thinking [of it]” (cf. Th 96; Th 207; Th 564 [316]). To an adulterer who asked if he should swear on oath that he had not committed adultery, he said “Perjury is no worse than adultery” (cf. Th 564 [317]). When asked what is difficult, he said “To know oneself.” What is easy? “To tell someone else what to do.” What is most pleasant? “Success” (cf. Th 362). What is divine? “That which has neither beginning nor end.” What had he seen that is hard to occur? “An aged tyrant” (cf. Th 119). How can one most easily endure misfortune? “If he sees his enemies even worse off.” What is the best and most just way to live? “If we do not do what we blame others for doing.” [37] Who is happy? “A person who is healthy in body, wealthy in soul, and well educated in nature” (cf. Th 564 [321a–h]). “Remember friends both present and absent,” he declares. “Do not beautify your face but be beautiful in the way you live.” “Do not acquire wealth in a bad way.” “Do not let your speech to your confidants accuse you.”334 “Whatever you have offered to your parents,” he says, “expect to receive from your children” (cf. Th 362). He said that the Nile floods when its streams are driven back by the etesian winds blowing in the opposite direction.

In his Chronicle (Th 67) Apollodorus says that he was born in the first year of the thirty-ninth Olympiad (624 BCE).335 [38] He was seventy-eight years old when he died (or ninety, as Sosicrates (Th 66) says). For he died in the fifty-eighth Olympiad (548–545336 BCE), having lived in the time of Croesus whom he promised to bring across the river Halys without a bridge by diverting the stream (547 BCE).

There were five others named Thales, as Demetrius of Magnesia reports in his Homonymies: the orator from Callatia who had an offensive, affected style; the painter from Sicyon, a genius; the third was very ancient, a contemporary of Hesiod, Homer and Lycurgus; the fourth is mentioned by Duris in his On Painting; the fifth is more recent, an obscure person mentioned by Dionysius in his Critica.

[39] The Sage died from heat, thirst and frailty while watching an athletic contest, when he was already old. His tomb bears this inscription (Th 56):

This tomb is small, but the fame reaches heaven.

Gaze upon it – the tomb of Thales the great genius.

There is also this epigram to him in the first book of my Epigrams, or Poems in all Meters [= A.P. 7.85].

Once while he was watching an athletic contest, Zeus, God of the

Sun,

you took the Sage, Thales, away from the stadium.

I praise you for bringing him near you, for the old man

could no longer see the stars from the earth.

[40] His sayings include “Know thyself,” which Antisthenes says in the Successions was due to Phemonoe337 and that Chilon appropriated it to himself.

Concerning the Seven (since it is appropriate to treat them generally here) the following kinds of accounts are given. Damon of Cyrene, who wrote On the Philosophers finds fault with everyone, and especially the Seven. Anaximenes338 says that they all applied themselves to poetry. Dicaearchus, however, says that they were neither sages nor philosophers, but intelligent people and lawgivers. Archetimus of Syracuse reported their conversation before Cypselus339 at which he says that he himself was present. Ephorus said that the conversation occurred at the court of Croesus without Thales. Some also declare that they met at the Panionion, in Corinth, and at Delphi. [41] There is also disagreement about their sayings, which are variously attributed to them, as in this case:

It was the Sage Chilon of Lacedaimon who said this:

“Nothing in excess.” “All good things come at the right time.”

There is even disagreement about their number. In place of Cleobulus and Myson Leandrius admits Leophantus, the son of Gorgias, from Lebedos or Ephesus, and Epimenides of Crete. In the Protagoras Plato admits Myson instead of Periander. Ephorus admits Anacharsis instead of Myson. Others add Pythagoras as well. Dicaearchus (Th 36) gives four who are agreed on: Thales, Bias, Pittacus and Solon, and he names six others of whom we are to select three: Aristodemus, Pamphylus, Chilon of Lacedaimon, Cleobulus, Anacharsis, and Periander. Some add Acousilaus of Argos, the son of Cabas or Scabras. [42] Hermippus in On the Sages340 (Th 59) said that there were seventeen, of whom different people chose different ones. They are Solon, Thales, Pittacus, Bias, Chilon, Myson, Cleobulus, Periander, Anacharsis, Acousilaus, Epimenides, Leophantus, Pherecydes, Aristodemus, Pythagoras, Lasus of Hermione, the son of Charmantides or Sisymbrinus (or as Aristoxenus has it, of Chabrinus), and Anaxagoras. Hippobotus in his Catalogue of Philosophers (Th 65) has Orpheus, Linus, Solon, Periander, Anacharsis, Cleobulus, Myson, Thales, Bias, Pittacus, Epicharmus and Pythagoras.

The following letters are attributed to Thales.341

Thales to Pherecydes

[43] I learn that you are the first of the Ionians who will reveal accounts of divine matters to the Greeks. Perhaps your proposal to publish the book is correct, instead of entrusting it to anyone at all to no profit. But if it is pleasing to you, I am willing to discuss whatever you are writing, and if you ask I will come to see you in Syros. For Solon of Athens and I would not be sensible if after sailing to Crete to investigate what is there and sailing to Egypt to talk with however many priests and astronomers are there, not to sail to you. For Solon will come too if you permit. [44] On the other hand you prefer to stay at home and rarely come to Ionia, and do not long for the company of foreigners. But, as I hope, apply yourself to only one thing, your writing. On the other hand, we who write nothing travel around Greece and Asia.

Since you have withdrawn from Athens, I think it might be agreeable to you to make yourself a home in Miletus, which is a colony of your people. For here too there is nothing to fear. But if you are worried that we in Miletus have a tyranny (since you have a strong hatred of monarchs), at least you will enjoy living with us as companions. Bias has invited you to come to Priene, and if the city of Priene is more pleasant for you, take up residence there and we will come and live with you.

Th 238342

Letter of Pherecydes to Thales; Thales as author.

Lives of the Philosophers 1.122

(Pherecydes to Thales) May you die well when the need comes. I was taken by illness when I had received the writings from you. Wasting away, I had a raging fever and I caught the ague. So I instructed my servants to bring the writing to you after burying me. If you and the other Sages think it a good idea, make it public, but if you do not, do not make it public. It did not yet please me, but there is no being sure about things, and I do not at all promise that I know the truth in all I declare as I speculate about the gods. But you should understand the rest. For everything I say is a riddle. Suffering even more from my illness I visited none of the doctors or any of my associates. To those who were standing by the door and asking what it was, I put a finger through the keyhole and showed them how I was raging from the disease. And I told them to come the next day to the burial of Pherecydes.

Th 239343

Thales as founder of Ionian philosophy; Thales and Anaximander.

Lives of the Philosophers 1.122 B

Those too who were called Sages, with whom some include the tyrant Pisistratus. But I must speak about philosophers, and I must begin with Ionian philosophy, which Thales founded, whose pupil was Anaximander.

Th 240

Thales’ death, variant on the story of his fall into a well; Thales as astronomer.

Lives of the Philosophers 2.4

(Anaximenes to Pythagoras) By good fortune Thales reached old age, but he was not fortunate in his death. He went out from his home one evening with his servant, as he used to do, and was observing the stars, and while he was observing he stepped off a steep place (since he did not remember it344) and fell. That was the end of the Milesians’ expert on the heavens. But we who conversed with him345 remember the man, and so do our children and those who converse with us346. Moreover we have expertise with his doctrines. Let the origin of every doctrine be attributed to Thales.

Thales and Pherecydes.

Lives of the Philosophers 2.46.6–11

According to what Aristotle says in the third book of the Poetics [On Poets] (Th 34), Antilochus of Lemnos tried to rival [Socrates] [ ...] and Pherecydes [tried to rival] Thales (Th 3).347

Th 242348

Xenophanes and Thales.

Lives of the Philosophers 8.1

Now that we have gone through Ionian philosophy, which originated with Thales, and [have gone through] the noteworthy men who contributed to it, let us now deal with Italian philosophy.

Th 243

Xenophanes and Thales.

Lives of the Philosophers 9.18.14–16

He [Xenophanes (Th 6)] is said to have contradicted Thales and Pythagoras and to have attached himself to Epimenides.

Porphyry (ca. 234–305/10 CE)

Thales’ prediction of an eclipse.

Commentary on Aristotle’s Categories 4.1.120.18–23

Since it is possible to know and predict eclipses of the sun and moon, as has in fact been discovered, but prior to Thales [it was] not yet [possible] although the knowable [fact] existed. But whereas the elimination of the knowable eliminates the knowledge too, the elimination of the knowledge does not eliminate the knowable. Therefore the knowable is prior and the knowledge is posterior, since they are relatives but not simultaneous.

Th 245

Cyril cites Porphyry, who in his history of philosophy reported the report of the travels of the golden tripod.

203 F Smith (cf. Th 509) and 425 F Smith; cf. Th 375 (Cyril Against Julian 1.38, 544D–545B)

Th 246

According to Porphyry, Thales is possibly the author of the saying “Know thyself.”

273 F Smith, cf. Th 365 (Stob. Anth. 3.21.26)

Th 247

According to Porphyry, Thales was the first of the “Seven Philosophers.” 194b T Smith, cf. Th 505 (Ibn an-Nadīm, Fihrist 245.12–15)

Th 248

Dating of Thales through Porphyry.

204 F Smith, cf. Th 500 (Siwan al-hikma 176–187), cf. Th 529 (Aš-Šahrastānī, Book of Sects and Creeds 2.167.9-13, Th 557 (Barhebraeus, History of the World 51.1-8)

Iamblichus of Chalcis (ca. 240–325 CE)

Thales’ association with Pythagoras.

Life of Pythagoras 2.11–12 [ ...] With him [Hermodamas] he [Pythagoras] crossed over to Miletus to see Pherecydes, Anaximander the natural philosopher, and Thales. [12] He met with each in turn and conducted himself so well that everyone liked him and admired his nature and invited him to join in their discussions. Thales in particular was delighted with his presence. He was struck by the difference between him and the other young men, which was greater than the reputation he had already gained and in fact surpassed it by far. After teaching him as much as he could, blaming his old age and weakness, he encouraged him to sail across to Egypt and especially to converse with the priests at Memphis and Diospolis, since he himself had been educated by them in the subjects that gave him a reputation among the many as a sage. He used to say that in fact he had not achieved so many successes either by nature or by practice as he saw that Pythagoras would. And so he [Thales] proclaimed it as good news in every way: if he associated with the priests he had mentioned he would be divine and wise beyond all men.

Th 250349

Thales and Pythagoras.

Life of Pythagoras 3.13–14

He [Pythagoras] was helped by Thales in other things and particularly in not wasting time. For this reason he renounced wine, meat and gluttony most of all, limiting himself to light and easily digestible food, and as a result he needed little sleep and was alert and clean in soul and enjoyed the most strict and unimpaired health of his body. He then sailed to Sidon, since he had found out that it was by nature his native country and because he correctly supposed that from there his crossing to Egypt would easier. [14] [ ...] Moreover he had learned that there were some practices there [in Sidon] that were somehow derived from and descended from the rituals in Egypt and hoped as a result that in Egypt he would participate in better, more divine and authentic initiation rites. Delighted at the advice of his teacher Thales he crossed without delay with some Egyptian ferrymen who most conveniently had anchored just then on the shore beneath the Phoenician Mount Carmel, where Pythagoras used to spend much time at the sanctuary.

Th 251350

Thales’ fall into a well.

Protrepticus 14.P72–73 (ed. Des Places)

He did not even know that he did not know all these things, for he did not keep away from them for the sake of his reputation, but in truth the body lies and lives only in its own city, but thought, which considers all these things unimportant [P73] and as nothing, disdains them entirely and flies, as Pindar says, practicing geometry beneath the earth and on its surface, and practicing astronomy above the heaven, and everywhere investigating the entire nature of each whole entity among things-that-are, not condescending to the level of things nearby. For example they say that Thales fell into a well while studying the stars and gazing aloft, and a witty and amusing Thracian servant-girl made fun of him because he was so keen to know about what was up in the sky but failed to see what was behind him and next to his feet. The same joke holds for everyone who spends his life in philosophy. It really is true that a person like that fails to notice the person next to him or his neighbor; not only does he not notice what he is doing, he barely knows whether he is a human being or some other kind of creature, but he investigates what a human being is, what that kind of thing does and experiences that is different from other beings. And he makes a great effort to track these things down.

Th 252

Thales and geometry.

On the General Mathematical Science 21

They say that Thales, who was the first to discover not a few things in geometry, passed them on to Pythagoras. And so it would be fair for us to assign to Pythagorean mathematics all the mathematical speculations we have taken from Thales.

Thales’ definition of number.

Commentary on Nicomachus’s Introduction to Arithmetic 10–11 Quantity, i.e., number, Thales defined as “an organization of units”351 (in accordance with the doctrine held in Egypt, where he had pursued his studies).

Lactantius (ca. 250–325 CE)

Th 254

Thales the Sage and natural philosopher; water as first principle; his theological views.

Testimony of the poets and philosophers about God.

Divine Institutions 1.5.14–16

Here I stop my treatment of the poets. Let us turn to the philosophers, whose authority is weightier and whose judgment more certain, since they are believed to have pursued not imaginary matters but the investigation of the truth. [16] Thales of Miletus, who was one of the Seven Sages and is considered the first of all to have investigated natural causes, said water is that from which all things were generated, and that God is the mind which formed everything from water (cf. Th 72). Thus he located the matter of things in moisture, but he established the principle and cause of generation in God.

Th 255

Water as the first principle.

Heat and moisture as the divinely created fundamental elements of the world.

Divine Institutions 2.9.18

Heraclitus said that all things are generated from fire; Thales said [they are generated] from water. Each saw something, but still each one was wrong. If there were only one of those two things352, water could never be generated from fire, nor fire from water. But it is more true that all things originate from a mixture of both together.

Thales as natural philosopher.

Philosophy is not wisdom

Divine Institutions 3.14.4–5

But he [Lucretius] praised [someone] as a person who ought to have been regarded as a god, for the very reason that he discovered how to be wise, for he says: “Will it not be fitting for this man to be made worthy of a place among the number of the gods?” [Lucr. 5.50 f.] [5] from which it is clear that he wished to praise either Pythagoras, who first named himself a philosopher, as I said, or Thales of Miletus, who is reported to have been the first to discuss the nature of things.

Th 257

Thales the first philosopher.

The superiority of wisdom to philosophy.

Divine Institutions 3.16.12–13

Besides, that argument too, which the same Hortensius353 used, has much weight against philosophy: “From this it can be understood that philosophy is not wisdom, because its beginning and origin is apparent.”354 [Fr. 52 Grilli] [13] “When did there begin to be philosophers? Thales was first, I think. Indeed, that time is recent.”

Th 258

Thales’ theological views.

Epitome of the Divine Institutions 4.3

It is a lengthy task to review what Thales, Pythagoras and Anaximenes in earlier times, or later the Stoics Cleanthes, Chrysippus and Zeno, or what our Seneca, who followed the Stoics, or what Tullius [Cicero] himself declared about the highest God, since all of them attempted to define what God is and asserted that the world is ruled by Him alone and that He is subject to no other nature since every nature is generated by Him.

Arnobius the Elder (ca. 300 CE)

Water as the first principle.

Against the Heathens 2.9–10

Does each one of you not believe one author or another? What anyone has persuaded himself that another has truly said, does he not defend it as if by an obligation of trust? Does one who says that the origin of all [things] is [fire] or water, not believe Thales or Heraclitus? Does one who ascribes the cause to numbers not believe Pythagoras of Samos and Archytas? Does one who divides the soul into parts and posits incorporeal forms not believe Plato the follower of Socrates? [ ...]. [10] Finally, do not the originators and fathers of the above-mentioned views say what they say on the basis of a trust in their own guesswork? Did Heraclitus see things come into being through changes of fires, did Thales [see things come into being] through the condensation of water? Did Pythagoras see numbers combining; Plato the incorporeal forms; Democritus the collisions of indivisible bodies?

Eusebius of Caesarea (before 260–between 337 and 340 CE)

Th 260

Water as the first principle; Thales and Anaximander.

Preparation for the Gospel 1.7.16–8.3

You will find that most of the Greek philosophers agree with him [Diodorus Siculus]. On the present occasion I will set out for you from Plutarch’s Stromateis their views on principles and their differences and disagreements, which arose from conjectures, not from direct apprehension355. And not casually 356 but leisurely and with careful consideration observe the mutual differences of the authors I quote.

[8.1] They say that Thales was the first of all357 who supposed that water was the principle of all things, for all things are from it and return to it.

[2] After him Anaximander, Thales’ associate, declared that the Infinite contains the entire cause of both the generation and perishing of the universe 358, and that out of it the heavens, and, generally, all the cosmoi, which are infinite, have been separated off. He declared that perishing and, long before that, generation originated and that all of them [the cosmoi] were revolving from infinite ages past.359 The earth, he said, is cylindrical in shape, and its depth is a third of its breadth. He declared that what arose from the eternal and is productive of hot and cold was separated off at the generation of this cosmos,360 and a kind of sphere of flame from this grew around the dark mist about the earth like bark about a tree. When it was broken off and enclosed in certain circles, the sun, moon and stars came to be. He also said that in the beginning humans were born from animals of a different kind, since other animals quickly manage on their own and humans alone require lengthy nursing. For this reason they would not have survived if they had been like this at the beginning. These then are the views of Anaximander.

[3] They say that Anaximenes declared air to be the principle of all things, and that this is indeterminate361 in kind, but is determined by the qualities attached to it362, and that all things are generated according as this air undergoes a certain condensation or rarefaction. Its motion exists eternally. When the air was being felted, the earth was the first thing to come into being, and it is very flat. This is why it rides upon the air, as is reasonable; and the sun, the moon and the other heavenly bodies have the origin of their generation from earth. He said, for example, that the sun is earth, but through its swift motion it acquires a great deal of heat.

Water as the first principle.

Preparation for the Gospel 7.12.1

Thales of Miletus declared water to be the principle of all things; Anaximenes, air; Heraclitus, fire; Pythagoras, numbers [ ...].

Th 262

Thales the Sage and founder of Ionian philosophy.

Preparation for the Gospel 10.4.17–18 [The Greek philosophers got their wisdom from the ‘East’] Such is Pythagoras. The philosophy known as Italian first arose out of his succession. It merited this name from the time he spent in Italy. After this [philosophy] came the one originated by Thales, one of the Seven Sages, and it was called Ionian. Next Eleatic [philosophy], which registered Xenophanes of Colophon as its father. [18] But363 Thales, as some record, was a Phoenician, or as others have supposed, a Milesian. He too is said to have conversed with the prophets364 of Egypt.

Th 263

Thales as astronomer and theologian; his pseudonymous writings.

Preparation for the Gospel 10.7.10

In fact everyone unanimously agrees that the first Greeks who philosophized about things celestial and divine, like Pherecydes of Syros, Pythagoras and Thales, were pupils of the Egyptians and Chaldeans and wrote little. And the Greeks believe that these [writings] are the earliest of all and they hardly believe them to be authentic.

Th 264

Thales as Sage; his dates.

Preparation for the Gospel 10.11.34 (Citation from Tatian)

[Moses and the Prophets came before the Greek thinkers (10.11.1).] Now that these things have been proved I will briefly discuss the era of the Seven Sages. For Thales, the earliest of the men mentioned above, was born around the fiftieth Olympiad [580/79–577/6] and I have briefly discussed the theories of his successors.

Th 265

Thales the Sage, natural philosopher and astronomer; Thales and Anaximander.

A brief look at those who came after Moses.

Preparation for the Gospel 10.14.10–12

Of these seven, Thales of Miletus, the first Greek natural philosopher, discussed the solstices, eclipses, the phases of the moon and the equinoxes, and he became the most distinguished of the Greeks. [11] Anaximander, the son of Praxiades and a fellow Milesian, was Thales’ pupil. He was the first to construct gnomons to determine the solstices, the time, the seasons and the equinoxes. [12] Anaximenes of Miletus, the son of Eurystratus, was Anaximander’s associate, and Anaxagoras of Clazomenae, the son of Hegesibulus was his [Anaximenes’].

Th 266365

Thales the first philosopher; his dates.

Preparation for the Gospel 10.14.16

Leucippus was his [Zeno’s] pupil, Democritus was Leucippus’s, and his [Democritus’s] student was Protagoras, during whose lifetime Socrates flourished. It is possible to find other natural philosophers too here and there who were born before Socrates. But all who began from Thales appear to have flourished under King Cyrus of Persia. Cyrus, it is clear, was born long after the Jewish people’s captivity in Babylonia.

Th 267366

Thales as natural philosopher.

Preparation for the Gospel 11.2.2–3

Plato was the first person to assemble all the parts of philosophy into one and did so more successfully than anyone else. Previously they had been scattered and dispersed like the limbs of Pentheus, as someone said, but he revealed philosophy to be a body and a complete animal. [3] For neither did Thales, Anaximenes, Anaxagoras and their associates [manage to do this] nor did all those who were born in the time of those men and are unknown. All of them spent their time solely on the investigation of the nature of things-that-are.

Th 268

Thales as natural philosopher.

Preparation for the Gospel 11.3.1 (from Aristocles, cf. Th 97)

If ever anyone else has ever practiced philosophy truly and completely, it was Plato. For Thales and his followers spent their time pursuing natural philosophy, and Pythagoras and his associates concealed everything.

Th 269367

Thales’ fall into a well.

Plato’s view of the true philosopher is quoted from the Theaetetus as well as the anecdote of Thales falling into a well.

Preparation for the Gospel 12.29.4–5

What do you mean by this, Socrates: “For example, Theodorus, they say that Thales fell into a well while studying the stars and gazing aloft, and a witty and amusing Thracian servant-girl made fun of him because he was so keen to know about what was up in the sky but failed to see what was behind him and next to his feet. [5] The same joke holds for everyone who spends his life in philosophy. It really is true that a person like that fails to notice the person next to him or his neighbor; not only does he not notice what he is doing, he barely knows whether he is a human being or some other creature, but he investigates what a human being is, what that kind of thing does and experiences that is different from other beings. And he makes a great effort to track these things down. Do you understand, Theodorus, or don’t you?”

Th 270368

Thales’ practical wisdom.

Quotation of Plato’s criticism of Homer in Republic, book 10, with his comparison of Homer with Thales and Anacharsis (Th 22).

Preparation for the Gospel 12.49.6

“Or, as happens with the achievements of a wise man, are many ingenious discoveries in the crafts or in other activities [attributed to Homer], as they are to Thales of Miletus and Anacharsis of Scythia?” There is nothing at all of this sort.

Th 271

Thales the Sage and founder of Ionian philosophy; his association with Egypt; water as the first principle.

In the following passages from Pseudo-Plutarch, Eusebius mentions Thales among others to refer to the disagreements among the natural philosophers.

Preparation for the Gospel 14.14.1

“Thales of Miletus”, one of the Seven Sages, “declared that water is the principle of things-that-are. This man is thought to have been the founder of philosophy and the Ionian school was called after him. For there have been very many schools. After practicing philosophy in Egypt he came to Miletus when quite an old man. He says that all things are from water and all things are dissolved into water. He bases this conjecture first on the fact that the seed, which is a moist substance, is the principle of all living things. Thus it is likely that indeed all things have their principle from moisture. Second, that all plants are nourished and bear fruit because of moisture, and dry up when they lack it. Third, that even the very fire of the sun and stars is nourished by the exhalations of waters, and so is the cosmos itself. This is why Homer too posits this judgment about water: “Okeanos which is the origin of all things.”369 Thales held these views.

Thales’ theological views.

Preparation for the Gospel 14.16.6

Thales [holds that] the cosmos is God. (cf. Th 149)

Th 273

Thales’ cosmology.

Preparation for the Gospel 15.29.3

Thales and his followers [hold that] the moon is illuminated by the sun.370

Th 274

Thales’ cosmology.

Preparation for the Gospel 15.30.1

Thales [holds that] the stars are earthy and fiery.

Th 275

Thales’ views on the nature of the soul.

Preparation for the Gospel 15.43.2

Thales, Pythagoras, Plato and the Stoics [hold that] daimons exist as spiritual substances, that heroes are souls separated from bodies, and that good souls are good [heroes] and evil [souls] are evil [heroes].

Th 276

Thales’ views on matter.

Preparation for the Gospel 15.44.2

Thales and Pythagoras and their followers, and the Stoics [hold that] matter is changeable and alterable, and is fluid through and through371.

Thales’ explanation of eclipses.

Preparation for the Gospel 15.50.1

Thales was the first to say that the sun is eclipsed when the moon, which is earthy, comes perpendicularly underneath it, and that this is observed in a mirror when a dish is placed below.

Th 278

Thales’ cosmology.

Preparation for the Gospel 15.55.1

Thales and his followers [hold that] there is one earth.

Th 279

Thales’ cosmology.

Preparation for the Gospel 15.56.1

Thales and the Stoics [hold that] the earth is spherical.372

Th 280

Thales’ cosmology.

Preparation for the Gospel 15.57.1

Thales and his followers [hold that] the earth is in the middle (cf. Th 162).

Th 281

The Chronicle of Eusebius is preserved in Greek only in fragments. The second part of the work is preserved in a Latin reworking of Hieronymus (cf. Th 304–308). A complete version of the Chronicle is found only in an Armenian translation of the sixth cent. See notes on Th 306 and Th 308. Chronicle 13.19–14.1 (ed. Hahn)

Chronicle 88b.19(k), cf. Hier. Chron. Th 305

Chronicle for the year 747 BCE

Th 283

Chronicle 96a9–12(b), cf. Hier. Chron. Th 306

Chronicle for the year 640 BCE

Th 284

Chronicle 100b.25(f), cf. Hier. Chron. Th 307

Chronicle for the year 586 BCE

Th 285

Chronicle 103b.12(h), cf. Hier. Chron. Th 308

Chronicle for the year 548 BCE

Pseudo-Valerius Probus (scripta Probiana) (4th cent. CE)

Th 286

Commentary on Vergil’s Eclogues 6.31

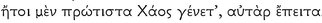

Some have given the role of principles to the individual elements: Parmenides of Elea, earth; Hippasus of Metapontum and Heraclitus of Ephesus, who is called  [obscure], fire; Anaximenes of Lampsacus,373 who is thought to be the first to have introduced natural philosophy, air; Thales of Miletus, his teacher, water. In fact they think that this view of Thales derived from Hesiod who said,

[obscure], fire; Anaximenes of Lampsacus,373 who is thought to be the first to have introduced natural philosophy, air; Thales of Miletus, his teacher, water. In fact they think that this view of Thales derived from Hesiod who said,  . [“First of all Chaos came into being, and then ...”].374

. [“First of all Chaos came into being, and then ...”].374

Chalcidius (4th cent. CE)

Water as the first principle.

Commentary on Plato’s Timaeus 280 [51A7]

But all of these [Pythagoras, Plato, Aristotle and the Stoics] establish it [matter] as formless and without any quality, whereas others have granted it form, like Thales, who they say investigated the secrets of nature before anyone else, when he said that the origin375 of things is water – I suppose because he saw that all nourishment of living things is moist. Homer is found to share the same view when he says that Okeanos and Tethys are the parents of generation376 [Il. 14.201] and when he establishes water, which he calls Styx [Il. 15.37], to be that by which the gods swear oaths377, attributing reverence to its great age and asserting that nothing is more revered than an oath. But Anaximenes, in judging air the origin378 of things – the origin379 of water itself as well as the other bodies – does not agree with Heraclitus who thinks that fire is the principle of things.

Th 288

Water as the first principle.

Commentary on Plato’s Timaeus 325 [49D]

In the cycle of the elements, [Thales’ water] appears never in the same form. [ ...] He assumes it in order to treat more completely the change of the elements into one another. For he says: “Since the bodies are in turn borrowing strength and nourishment for generation from one another in a cycle and do not remain in one and the same form, what certain and unhesitating apprehension can there be of them? None, of course.” And rightly. Let380 us suppose that this fire is pure and is uncontaminated by other matter, as Heraclitus thinks, or water, as Thales does, or air, as Anaximenes does: “If we think that these are always the same and unchangeable,” he [Plato] says, “we will fall into many incurable errors.”

Commentary on Plato’s Timaeus 332 [50E]

The receptacle always receives everything without ever in any way taking on a form similar to any of the things that enter it [Timaeus 50B].

[ ...] And he concludes by asserting that everything that will be able to receive forms well and skillfully must be without a form of its own and free from everything that it will receive – that is, without shape or color, and also without odor or anything else that is an attribute of bodies. For if the receptacle is to be like anything that it receives, when it encounters anything that is unlike the things to which it is like, its features will be at odds, I think, with the features of the body that has entered it and it will express no likeness. What381 he means is this: if water is the matter or substance of all things, as Thales thinks, it will surely have qualities that are appropriate to its own proper nature that will never depart from it. However, if it is necessary for it to depart from its own nature to any extent, and become fire, it will surely take on fiery qualities in turn. But the moist and the fiery are contrary to one another, since moisture and cold are properties of the former and dryness and heat of the latter. “Therefore,” he [Plato] says, “these are different and opposed to one another, and neither of them will allow the quality of the other to be expressed purely, since heat will fight against cold and dryness will destroy moisture.

Pseudo-Ausonius (4th cent. CE?)

Th 290382

Thales the Sage; his wise sayings.

Appendix A, Moralia Varia, 2. On the Seven Sages from the Greeks

I will set out in seven verses the lands, names and sayings

of the Sages; they will speak every one of them their own single-verse

sayings.

Chilon, whose land is Lacedaimon: “Know thyself.”

Periander of Corinth: “Control agitated anger.”

Pittacus, from the shores of Mitylene: “Nothing in excess.”

“Measure is best in things,” says Cleobulus of Lindos.

Solon, born in Athens, teaches us to “Wait for the end.”

Bias, whom famous Priene [bore, teaches] that “Most people are bad.”

Thales, the child of Miletus, to “Avoid giving pledges.”383

Pseudo-Justin Martyr (early 4th cent. CE)384

Thales the Sage and founder of natural philosophy; water as the first principle.

Hortatory Address to the Greeks 3.1–2

Now since it is appropriate to begin with the ancient and first Sages I will begin from there and set out the view of each of them, which is far more ridiculous than the theology of the poets. [2] For Thales of Miletus (cf. Th 147), who was the first founder of natural philosophy, declared water to be the principle of all things-that-are385, for, he says, all things386 are from water and all things387 are dissolved into water. [The doctrines of Anaximander and Anaximenes follow.] All these men, the successors of Thales, pursued natural philosophy, as they called it.

Th 292

Thales the first philosopher; water as the first principle.

The religious opinions of Plato and Aristotle cannot be foundations for true belief. They contradict one another.388 Justin here fastens on a passage from the pseudo-Aristotelian On the World, in which God’s transcendence is emphasized with quotations from poetry.

Hortatory Address to the Greeks 8.3–4

For he [Aristotle] wrote,389 “Homer said this too: ‘Zeus was allotted the broad heaven in the aether and the clouds.’” [Il. 15.192], wishing by the testimony of Homer to prove that his own view is trustworthy. But he did not know that if he used Homer as a witness to demonstrate that he is speaking the truth, many of his views will evidently not be true.

[4] For Thales of Miletus, the first founder of philosophy among them, will take this pretext from him to deny Aristotle’s own opinions about principles. For whereas he [Aristotle] declared that god and matter are the principles of all things, Thales, the earliest of all their Sages, says that water is the principle of things-that-are; for, he says, all things390 are from water and all things391 dissolve into water (cf. Th 147). He bases this conjecture first on the fact that the seed of all living things, which is their principle, is moist; second that all plants are nourished and bear fruit because of moisture, and dry up when deprived of moisture. Then, as if he is not satisfied by his conjectures he calls Homer too as a witness as if he were saying something worth believing: “Okeanos, who is ordained the origin of all things.” [Il. 14.246] How, then, will Thales not reasonably say to him, “Why, Aristotle, when you want to eliminate Plato’s views, do you refer to Homer as if he is telling the truth, but when you state a view that is contrary to ours, you think that Homer is not telling the truth?”

Epiphanius (between 310 and 320–403/2 CE)

Th 293392

Thales the Sage; water as the first principle.

On Belief 3.504.32–505.3

These are the beliefs that come from the Greeks, among which I would rank first from the beginning the judgment and view of Thales of Miletus. [505] For Thales of Miletus, one of the Seven Sages, himself declared that water is the origin of all things. For he said that all things are from water and dissolve again into water (cf. Th 147).

Decimus Magnus Ausonius (ca. 310–394 CE)

Thales the Sage; his wise sayings.

The Masque of the Seven Sages 69–70

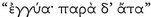

But Thales produced  ,

,

he who forbids us to give a pledge because disaster is at hand.

Th 295

Thales the Sage; his wise sayings.

The Masque of the Seven Sages 162–188

Thales comes.

I am Thales of Miletus, who declared that water is the origin

for the generation of things, as did the poet Pindar.

...

[to whom] fishermen gave [the golden tripod] pulled out of the sea.

For they had chosen me at the command of the god of Delos,

because he had sent this as a gift to a Sage.

I declined and did not accept it, and returned it

to be taken to others I deemed superior.

Then, when to each of the Seven Sages

it had been sent and sent back, they brought it again to me.

I accepted it and dedicated it to Apollo.

For if Phoebus bids a Sage be chosen,

it is fitting to believe that he does not mean any human but a god.

That man, then, am I. But the reason for

my appearing on this stage, as with the two who have come before me,

is to become the proponent of my own saying.

It will offend some, but not the sensible

whom experience has taught and made clever.

Behold:  ,we say in Greek;

,we say in Greek;

in Latin, “Sponde; praesto sed noxa tibi.” [Give a pledge, but Disaster stands

nearby.]

I could run through a thousand instances to prove

that bonds and bails are charged with the crime of regret.

But I do not care to mention anyone by name.

Let each of you mention such to himself and consider

how many have suffered loss and harm by giving a pledge.

May this service continue to bring pleasure – but to both parties!

Clap, then, some of you; the rest, offended, hiss me off the stage.

Flavius Gaius Iulianus (Julian the Apostate) (Roman emperor 331/2–363 CE)

Thales’ reputation.

Sometimes we should not ask for an immediate reward, but instead should follow Thales’ example.

Oration 3.162.2–5

(Panegyric in Honor of the Queen [Eusebeia]) When someone asked him [Thales] how much pay he should give for what he had learned, [Thales] said “if you agree that you have learned from me, you will pay me my worth.”

Th 297

Cyril quotes a comparison Julian made between outstanding Greek figures (including Thales) and Moses.

Against the Galilaeans Fr. 39 (ed. Masracchia) = Th 378 (from Cyril c. Iul. 6.184B–D)

Libanius (314–393 CE)

Th 298

Thales and other philosophers are not responsible for political and military disasters.

Declamations 1.158

(Apology of Socrates) But who would not lament if Bias has a bad reputation – the associate of Solon and the friend of the Pythian god who from Delphi gives advice to all men – and [if] along with Bias many others who made Ionia respected [had bad reputations]? It was not because of Melissus, Thales or Pythagoras that they were subjected and that men who had power in the cities fell into factional strife. Factions are a universal illness of human nature, and their being subjects resulted from the mighty royal power that attacked them, but it was not Pythagoras or Melissus who created the strength of the Persians, but Cyrus, by dethroning Croesus, and Darius after him.

Thales’ reputation.

Declamations 2.9

(They prevent Socrates in prison from conversing and someone objects.) “He is both wicked393 and condemned.” Suppose he is wicked. Suppose that there is nothing untrustworthy394 in the indictment and in Anytus’s and Meletus’s charges. I know well that there will come a time when someday you will revere Socrates as the Ephesians do Heraclitus, the Samians Pythagoras, the Lacedaimonians Chilon, the Milesians Thales, the Lesbians Pittacus, the Corinthians Periander, and you yourselves Solon. For the malice of their neighbors is set against all sages when they are alive, but when they are dead their wisdom is judged clearly by awareness that is without pain.

Themistius (ca. 317–ca. 388 CE)

Th 300

Thales the Sage; his wise sayings; the founder of natural philosophy; his prediction of an eclipse; Thales not an author.

In an excursus in his twenty-sixth oration, Themistius goes into the history of philosophy, which made progress through constant innovations.

Oration 26.317A–C

For earlier only a few sayings of Thales of Miletus were in circulation –of Thales himself and the other Sages. But nowadays walls and signs are covered with them – useful and intelligent [B] enough, with as much intelligence as there can be in two words,395 but short on argument, in the form of commands, and urging us towards but a small part of excellence. Later on Thales in his old age was the first to treat of nature; he looked up at the sky, studied the stars, and predicted publicly to all the Milesians that there would be night during the day and the sun would set aloft and the moon would get in its way so that its light and its rays would be cut off. So much did Thales contribute, but he did not put down his discoveries in a treatise –[C] neither Thales himself nor any of his contemporaries. Anaximander, the son of Praxiades, became his follower, but did not follow him alike in all matters. He immediately changed this practice and went in a new direction by being the first of the Greeks we know of to dare to bring out a written account of nature. Writing accounts had previously been a disgrace, and was not customary among the Greeks before his time.

Thales’ views on the nature of the soul.

Paraphrase of Aristotle’s On the Soul 3.13.21–25 [de an. 1.2.405a2–b8]

Thales too seems to suppose that the soul is something that causes motion, if in fact this is why he said that iron is attracted by a magnet396 because that stone is animate. In this way too Anaximenes, Diogenes and everyone who says that the soul is air attempt to preserve both properties, that it causes motion by its fine nature and that it has knowledge because it is posited as principle.

Th 302

Thales’ views on the nature of the soul.

Paraphrase of Aristotle’s On the Soul 3.35.26–29 [de An. 1.5.411a7–8]

There is another view about the soul in addition to the ones already mentioned – that the soul is intermingled in every thing-that-is and pervades the entire cosmos, every part of which is animate. This view is the reason why Thales too believed that all things are full of gods.

Himerius (ca. 320–after 383 CE)

Declamations and Orations 28.8

Pindar sang to the music of the lyre of the glory of Hieron at the Olympic festival. Anacreon sang of the fortune of Polycrates which brought offerings to the goddess of Samos.397 And Alcaeus sang of Thales398 (Th 1) in his odes when Lesbos celebrated its festival.

Jerome (between 331 and 348–419/20 CE)

Th 304

Thales the Sage; his dates.

Translation of Eusebius’s Chronicle, Preface 13.19–14.1

Homer is found to be much earlier than Solon, Thales of Miletus, and the others who along with these men were called the Seven Sages.399

Th 305

Thales’ dates.

Translation of Eusebius’s Chronicle for the year 747 BCE

Thales of Miletus, the natural philosopher, is known.400

Thales’ dates.

Translation of Eusebius’s Chronicle for the year 604 BCE

Thales of Miletus, the son of Examyas, the first natural philosopher, is known.401 They say that he lived until the 58th Olympiad [548–545].402

Th 307

Thales’ prediction of an eclipse.

Translation of Eusebius’s Chronicle for the year 586 BCE

There was an eclipse of the sun which Thales had predicted would take place [ ...] Alyattes and Astyages fought a battle [582].403

Th 308

Thales’ dates.

Translation of Eusebius’s Chronicle for the year 548 BCE

Thales dies.404

Ambrose of Milan (ca. 340–397 CE)

Water as the first principle.

Hexaemeron 1.2.6

Although he [Moses] took his name from water, he did not think it should be said that all things are made of water as Thales did, and although he was educated in a royal palace he preferred because of his love of justice to undergo voluntary exile rather than live a life of sinning for the sake of pleasure in a powerful position under a tyranny.

Tyrannius Rufinus (345–410 CE)

Th 310405

Water as the first principle.

Pseudo-Clementinus, Recognitions 8.15.1–3

For when the Greek philosophers investigated the principles of the world, different ones went different ways. Indeed Pythagoras declared that the elements of principles are numbers; Callistratus, qualities; Alcmeon, contraries; Anaximander, immensity; Anaxagoras, equalities of parts; [2] Epicurus, atoms; Diodorus, amere, that is, things in which there are no parts; Asclepiades, masses, which we can call tumors or excrescences; geometers, limits; Democritus, ideas; Thales, water; [3] Heraclitus, fire; Diogenes, air; Parmenides, earth; Zeno, Empedocles and Plato, fire, water, air, earth.

Augustine (354–430 CE)

Thales the Sage, founder of Ionian philosophy and author; his prediction of eclipses; water as the first principle; Thales and Anaximander.

City of God 8.2

The founder of the Ionian kind [of philosophy], however, was Thales of Miletus, one of the men who were called the Seven Sages. The remaining six were distinguished for their way of life and for certain precepts for living a good life, while Thales,406 in order that he might have a series of successors, investigated the nature of things and presented his findings in writings which made him prominent. He was greatly admired for his ability to predict eclipses of the sun and moon through his understanding of astronomical calculation. Nevertheless he held that water is the principle of things and that from it are generated all the elements of the world, the world itself, and all that comes to be in it. However, over this work, which we observe to be so wonderful when we contemplate the world, he placed nothing that stems from divine intelligence.

His pupil Anaximander succeeded him, but held a different view about the nature of things. He did not think that all things are generated from a single substance, as Thales [held that they are generated] from moisture, but that each thing is generated from its own proper principles. He believed that these principles of individual things are infinite, and that they bring into being countless worlds together with everything that comes to be in them. He thought that these worlds perish at times and at times are born again, depending on how long each one can persist. He too gave no role in these works to divine intelligence. He left as his student and successor Anaximenes, who assigned the causes of all things to air, which is infinite. He did not deny the existence of the gods or keep silent on the matter, but he believed not that air was created by them, but that they themselves came to be from air. But Anaxagoras, his pupil perceived a divine creator of all these things that we see, and said that [they come] from infinite matter which consists of particles of all things similar to one another, from which individual things are made, each from its own and appropriate kinds, through the agency of a divine intelligence. Diogenes, another pupil of Anaximenes, also said that air is in fact the matter of things from which everything comes to be.

Th 312

Water as the first principle.

All the other pagan philosophers and theologians must give way before the Platonists.

City of God 8.5

But let the other philosophers too, who held that the principles of nature are corporeal because their own minds are dedicated to the body, yield to these men [the Platonists] who are so great and who know so great a God. Such were Thales [who found the principle of nature] in moisture, Anaximenes [who found it] in air, the Stoics in fire, Epicurus in atoms [ ...].

Th 313

Thales the Sage; his dates.

City of God 18.24

Also during the reign of Romulus Thales of Miletus is said to have lived. He was one of the Seven Sages who, coming after the theological poets (among whom Orpheus became famous above the rest), were called  , which in Latin means “sapientes.”407

, which in Latin means “sapientes.”407

Th 314

Thales the Sage and natural philosopher and author of treatises.

City of God 18.25

At that time [the Babylonian captivity of the Jewish people] Pittacus of Mitylene, another of the Seven Sages, is said to have lived. Eusebius writes408 that the five others lived at the time when the people of God were held captive in Babylonia; when these are added to Thales, whom we mentioned above (Th 313), and this Pittacus, the total number that results is seven. They are these: Solon of Athens, Chilon of Lacedaimon, Periander of Corinth, Cleobulus of Lindos, Bias of Priene. All these,409 called the Seven Sages, who came later than the theological poets, were famous because they excelled the rest mankind in their particular praiseworthy manner of life and compressed a number of moral precepts into brief sayings. But they did not bequeath any literary monuments to posterity with the exceptions that Solon is said to have instituted certain laws for the Athenians and that Thales was a natural philosopher and left books containing his doctrines. At the time of the Jewish captivity Anaximander, Anaximenes and Xenophanes were also famous as natural philosophers.

Th 315

Thales as founder of natural philosophy; his dates; Thales and Anaximander.

The pagan philosophers came later than the prophets.

City of God 18.37

If we add to them the earlier men also, who were not yet called philosophers, namely, the Seven Sages, and after them the natural philosophers who succeeded Thales and followed his interest in investigating the nature of things, namely Anaximander, Anaximenes, Anaxagoras and some others, before Pythagoras was the first to profess himself a philosopher – even those men do not precede all of our prophets. For Thales, who was earlier than the rest, is said to have achieved eminence during the reign of Romulus, the era when the stream of prophesy burst forth from Israel’s springs in the writings that were to irrigate the whole world.

Th 316

Thales the Sage and natural philosopher.

Against Julian [of Eclanum] 4.15.75

You have also summoned a crowd of philosophers to aid you in your undertaking, so that, if the natural cleverness of beasts cannot bring aid, at least the errors of learned men may do so. But who cannot see that you were aiming to make an ostentatious display of learning by mentioning the names of learned men and various schools, since anyone who reads those writings of yours sees clearly that this has nothing to do with the subject we are discussing? For who can hear the ones you have mentioned (cf. Th 325): “Thales of Miletus, one of the Seven Sages, then Anaximander, Anaximenes, Anaxagoras, Xenophanes, Parmenides, Leucippus, Democritus, Empedocles, Heraclitus, Melissus, Plato, the Pythagoreans” – each with his own theory about natural phenomena. Who, I say, can hear this and not be frightened by the clamor of names and schools piled up (if like most people he is uneducated) and think that you, who can know them, must be a great person?

Servius Grammaticus (4th/5th cent. CE)

Th 317

Water as the first principle.

Commentary on Vergil’s Aeneid 3.241

“Birds of the sea” [the Harpies] because they are called the daughters of Pontus and Terra. This is why they live on islands, and possess a part of the land and a part of the sea. Others say that they are daughters of Neptune, who is the father of almost all monsters; this is reasonable, for according to Thales of Miletus all things are generated from moisture. This is the source of [the saying] “and Okeanos, the father of things” (Georgics 4.382). And this is why we generalize whenever parents are missing. Thus we call strangers whose parents we do not know sons of Neptune.

Th 318

Water as the first principle.

On differing burial customs in different cultures.

Commentary on Vergil’s Aeneid 11.186

But Thales, who maintains that all things are created from moisture, claims that bodies must be destroyed in order to be able to be dissolved into moisture. 410

Th 319

Water as the first principle.

Commentary on Vergil’s Eclogues 6.31

For he sang about how seeds are driven through the great void. There are many views of philosophers about the origin of things: some, like Anaxagoras, say that all things are generated from fire; others, like Thales of Miletus, [say that they are generated] from moisture, and this is the source of the expression “and Okeanos, the father.”

Commentary on Vergil’s Georgics 4.363

After returning they told that there are groves beneath the earth and an immense body of water that contains all things and from which all things are generated, and this is the source of the expression “and Okeanos, the father of things,” in accord with Thales.

Th 321

Water as the first principle.

Commentary on Vergil’s Georgics 4.379

He said “and Okeanos, the father of things” in accord with the natural philosophers, who declare that water is the element of all things. Thales was the first of these.

Th 322

Water as the first principle.

Commentary on Vergil’s Georgics 4.381

“And Okeanos, the Father,” in accord with Thales, as we said above (cf. Th 317 ff.).

Nemesius of Emesa (text ca. 400 CE)

Th 323

Thales’ views on the nature of the soul.

On the Nature of Man 2.68–69

There has been an endless disagreement among those who declare the soul to be incorporeal, some saying that it is an immortal substance, others that it is incorporeal but neither a substance nor immortal. For Thales411 was the first to declare that the soul is always-moving and self-moving (cf. Th 165), and Pythagoras412 [was the first to declare that it is] number that moves itself.

On the Nature of Man 5.169

For Thales too, who says that water is the only element, attempts to show that the other three are generated by it: its sediment becomes earth, its finest part becomes air, and the finest part of air becomes fire. On the other hand, Anaximenes, who says that air is the only [element], likewise attempts to show that the other elements are produced from air.

Julian of Eclanum (ca. 385–before 455 CE)

Th 325

Thales the philosopher and Sage.

Four books to Turbantius 2.148

(You have also called a crowd of philosophers to aid [ ...] For who can hear the ones you have mentioned) Thales of Miletus, one of the Seven Sages, then Anaximander, Anaximenes, Anaxagoras, Xenophanes, Parmenides, Leucippus, Democritus, Empedocles, Heraclitus, Melissus, Plato, the Pythagoreans[ ...].

Theodoret (ca. 393–ca. 466 CE)

Th 326

Thales’ association with Egypt.

Cure of the Greek Maladies 1.12

The most famous Greek philosophers whose413 memory is still now legendary among those who are respected – Pherecydes of Syros, Pythagoras of Samos, Thales of Miletus, Solon of Athens, and moreover Plato, the son of Ariston and pupil of Socrates, who surpasses all in the beauty of his language – did not shrink from exploring Egypt and Egyptian Thebes, Sicily and Italy for the sake of discovering the truth, even though in those times there was no single monarchy that ruled all the peoples, but there were different constitutions and different laws in the cities.

Thales’ ancestry.

Cure of the Greek Maladies 1.23–24

But if even the Greeks were taught the crafts and sciences, the cults of daimons and their first letters by the barbarians and are proud of their teachers, why do you, who cannot even understand the writings of those people, refuse to learn the truth from men who have received god-given wisdom? [24]414 But if you do not want to lend them your ears because they did not originate in Greece, it is time for you not to call Thales a sage or Pythagoras a philosopher or his teacher Pherecydes. For Pherecydes was from Syros, not Athens, Sparta or Corinth, and Aristoxenus, Aristarchus and Theopompus say that Pythagoras was a Tyrrhenian, while Neanthes calls him a Tyrian, and they call Thales a Milesian, but Leandrus (Th 50) and Herodotus (Th 12) called him a Phoenician.

Th 328

Thales’ fall into a well.

The difference between wisdom and useless science is supported through quotations from Plato.

Cure of the Greek Maladies 1.37

And in the Theaetetus (Th 19) he [Plato] attacks dabblers in astronomy, saying as follows:415 “For416 example, Theodorus, they say that while studying the stars, and gazing aloft, Thales fell into a well; and a witty and amusing Thracian servant-girl made fun of him because, she said, he was so keen to know about what was up in the sky but failed to see what was in front of him and next to his feet.”

Thales the Sage; water as the first principle; Thales and Anaximander. Cure of the Greek Maladies 2.8–9

If you cite the philosophers against us in your defense, know well that they too did a great deal of wandering. For they did not all have a single highway and they did not follow in the tracks of those who had gone before, but each one opened his own path and they thought up myriads of them. For the paths of falsehood have many branches. [9] And this will at once be shown explicitly. Thales, the earliest of those called the Seven Sages, supposed that water was the principle of all things, relying on Homer, I suppose, who had said, “Okeanos the origin of gods, and mother Tethys” [Il. 14.201]. But Anaximander, who succeeded him, declared that the infinite is the principle, while his successor Anaximenes, and Diogenes of Apollonia agreed in calling air the principle.

Th 330

Thales’ dates.

Cure of the Greek Maladies 2.50

Now if, according to Porphyry, Moses was more than a thousand years earlier than these, and these [Orpheus, Linus, Musaeus, etc.] were the earliest poets – for both Homer and Hesiod came after them, and these in turn were earlier by many years than Thales and the other philosophers, and Thales and his associates [were earlier] than those who practiced philosophy after them – why on earth do we not abandon all these men and turn to Moses, the ocean of theology, “from whom” (to say poetically) come “all rivers and every sea” [Il. 21.196]?

Thales’ views on matter.

Cure of the Greek Maladies 4.13

Thales, Pythagoras, Anaxagoras, Heraclitus and the flock of Stoics declared that matter is changeable, alterable and fluid (cf. Th 151).

Th 332

Thales’ cosmology.

Cure of the Greek Maladies 4.15–16

Not only on these topics417 but on the rest as well were they in the greatest disagreement. For Thales, Pythagoras, Anaxagoras, Parmenides, Melissus, Heraclitus, Plato, Aristotle and Zeno agreed that there is one cosmos, but Anaximander, Anaximenes, Archelaus, Xenophanes, Diogenes, Leucippus, Democritus and Epicurus held that there are many [cosmoi] and in fact an infinite number. [16] And some held that it is spherical, and others that it has other shapes; some that it whirls around like a millstone, others418 like a wheel; some that it is animate and breathes419, others that it is entirely inanimate; some that it is generated in thought420 but not in time, others that it is entirely ungenerated and uncaused; and these hold that it can perish, while those hold that it is imperishable.

Th 333

Thales’ cosmology.

Cure of the Greek Maladies 4.17

In addition Thales called the stars earthy and fiery.

Th 334

Thales’ cosmology.

Cure of the Greek Maladies 4.21

In addition, both the sun and the moon [ ...] Thales [called] earthy.

Th 335

Thales’ cosmology.

Cure of the Greek Maladies 4.23

And they speak nonsense about the moon in the same way; for Thales declares that it is earthy, while Anaximenes, Parmenides and Heraclitus [declare] that it consists only of fire.

Th 336

Thales’ views on the nature of the soul.

Cure of the Greek Maladies 5.17

Thales called the soul unmoved by nature (cf. Th 165).

Th 337

The Greek philosophers’ love of novelty; Thales and Anaximander.

Cure of the Greek Maladies 5.44–45

Authors, philosophers and poets have had such great strife and quarrels about the soul, the body, and the very constitution of man, some championing these views and others those, and still others giving birth to a view that is contrary to both. For they did not desire to learn the truth but, slaves to vanity and ambition, they longed to be called the discoverers of new doctrines. [45]421 This is why they did all their wandering, and those who came later overturned the views of their predecessors. Indeed when Thales was already dead, Anaximander made use of contrary doctrines, and after the death of Anaximander Anaximenes did the same, and likewise Anaxagoras.

Aponius (5th cent. CE)

Water as the first principle; Thales and geometry.

Commentary on the Song of Songs 5.22–23

Because these words are being repeated a second time in this Song [III 5],422 where for a second time “the daughters of Jerusalem are adjured by the roes and the stags of the fields,” it will not be displeasing to repeat the words of the other423 book. For in the former “adjuration of the daughters,” we said that in “roes and stags,” personifications of the philosophy of Thales and Pherecydes are meant to be understood.424 These doctrines are not permitted to be imported into Church doctrine, just as “roes and stags” are animals not commanded by Moses to be offered on the altar as a sacrifice to God, as lambs, calves and she-goats are to be sacrificed on the altar, but they are not reckoned among the unclean animals and the people are commanded to eat them after their blood has been spilled on the earth.425 So also the above-mentioned philosophy is not unclean for the reason that it harms the Creator like the life or doctrines of other philosophers, who are esteemed as comparable to wild beasts, dogs and pigs, because they teach that pleasure is the greatest good. The aforementioned philosophy is far from the insanity of these others and is distinguished by being compared with the above-mentioned animals. [23] Of these [philosophers], the one named Thales declared in his doctrine that water is the origin of all things, and that all things are made of and subsist by means of something invisible and great; he confirms, however, that the cause of motion is a spirit situated in water;426 and with his keen intelligence he also was the first to discover the art of geometry through which he supposed that there is one creator of all things.

Iohannes Stobaeus (5th cent. CE)

Thales’ theological views; his wise sayings.

Anthology 1.1.29a

(That god is the creator of things-that-are and directs the universe by the Logos of providence, and of what substance he is.) When asked “What is the oldest of existing things,” Thales answered, “God, for he is unbegotten” (cf. Th 90; Th 121; Th 237 [Diog. Laert. 1.35]; Th 564 [320a]).

Th 340

Thales’ theological views; his cosmology; water as the first principle. Anthology 1.1.29b

Thales [said that] god is the mind of the cosmos, that the universe427 is animate and also full of daimons, and that there pervades the elementary moisture a divine power that causes it to move.428

Th 341

Thales’ wise sayings.

Anthology 1.4.7a

(Concerning divine necessity by virtue of which things inexorably occur according to the will of god.) When asked “What is most powerful?” Thales said, “Necessity, for it rules all things” (cf. Th 121; Th 154; Th 123 [Diog. Laert. 1.35]; Th 564 [320e]).

Th 342

Thales’ wise sayings.

Anthology 1.8.40a

(Concerning the substance and parts of time and of how many things it is the cause.) When asked “What is wisest?” Thales said “Time, for it finds out everything” [ ...] Thales declared that time is the clearest proof of all things, since it brings the truth to light (cf. Th 121; Th 237 [Diog. Laert. 1.35]; Th 342; Th 564 [320 f.).

Water as the first principle.

Anthology 1.10.12.1–10

(Concerning the principles and elements of the universe429.) Thales of Miletus declared that water is the principle of things-that-are430, for he says that all things are from water and all things are dissolved into water. He bases this conjecture first on the fact that seed, which is moist, is the principle of all living things. Thus it is likely that all things have their principle from the moist. Second, from the fact that it is because of moisture that all plants are nourished and bear fruit, but dry up when they are deprived of it. Third, that even the very fire of the sun and the stars is nourished by exhalations from water, as is the cosmos itself (cf. Th 147).

Th 344431

Thales the founder of Ionian philosophy.

Anthology 1.10.12.47–53

Archelaus [held that] the air is infinite and that it undergoes condensation and rarefaction. Of these, the latter is fire, the former water. Now these men, who come one after another in the successions, make up Ionian philosophy, as it is named, because Thales, the man who founded it, was from the metropolis of the Ionians.

Th 345

Thales’ views on principles and elements.

Anthology 1.10.16b

Aristotle and Plato and their associates believe that principle and elements are different, but Thales of Miletus thinks that principle and elements are the same thing.

Thales’ views on matter.

Anthology 1.11.3

(Concerning matter.) Thales, Pythagoras and their followers down to the Stoics and including Heraclitus declared that matter is changeable, alterable, modifiable and fluid through and through.

Th 347

Thales’ views on the first cause.

Anthology 1.13.1d

(Concerning causes.) Thales and his successors declared that the first cause is unmoved.

Th 348

Thales’ views on matter.

Anthology 1.14.1i

(Concerning bodies and their division and about the smallest.) Thales and Pythagoras and their followers [held that] bodies are subject to being affected and are divisible ad infinitum, as are all things that are continuous: lines, surfaces, solid bodies, place, and time (cf. Th 152).

Th 349

Thales’ views on the elements.

Anthology 1.17.1