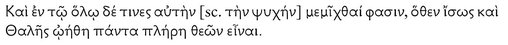

Paraphrase of Aristotle’s Categories 36.16–21

But if [perceptibles and knowables are taken] as perceptibles and knowables not actually (for how [could they be actually] if there is no perception or knowledge?) but potentially – if this [is done], of course both knowledge and perception, with reference to which these things [perceptibles and knowables] are spoken, will coexist potentially. For even if before Thales the moon existed, it existed as a thing but not as a knowable; but if it was also potentially knowable with respect to its eclipse, of course there was also potentially knowledge of the eclipse.

Anonymous (date uncertain)

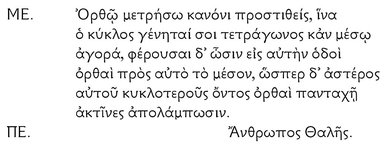

Th 568

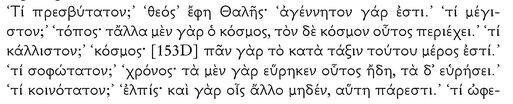

Thales’ wise sayings.

Poem on the Seven Sages (Anecdota Graeca I 143)

Last in turn spoke Thales straight out:

“Next door to a pledge dwells mischievous ruin.”

Th 569

Thales the Sage; water as the first principle.

Anthologia Latina 942

What the eyes perceive is god; in fact it is the source of gods.

The majesty of the heavens turns in its orb.

The earth moves in the bosom of itself and of the heaven

And each of them shows a limit of the huge sphere.

But Nature who yields herself to be seen in the sea

Says to the shining stars: “I have no limit.

Everything that is around me and above me – everything the law of

water pours forth.

Thus nowhere is there a limit of immense Ocean.

Here, therefore, do you direct your eyes to the ultimate origins of things,

Here all numbers and signs breathe their last:

From here is born all that dies and returns again;

To here returns all that perishes in the eternal orb.

This element destroys flames, and nourishes them, calls them forth, and

makes them grow.

Every Sage is far removed from Thales.”

Anonymous (date uncertain)

Th 569a

Fr. 2b Wehrli2, (Anecdota Graeca ed. I. Bekker (1814) I 233, 15)

Thales’ wise sayings

“Know thyself.” A saying. Some attribute it to Chilon. Hermippus declares that the eunuch Delphus stated it and had it inscribed on the temple. Chamaeleon declares that this maxim is Thales’.

Th 569b

CPF I 1* (29 Chamaeleon 1T), 403 (PSI 1093, 31-33 [II.3] (2nd cent. CE) Chamaeleon Thales, son of Hexamyas691

...

Anonymous (date uncertain)

Th 569c

CPF I 1* (1 Lista di scolarchi) p.81 f. (PDuke inv. G 178P (4th cent. CE) col. I

Thales a famous philosopher

The leading figures of philosophy ... Thales of Miletus, Anaximander of Miletus, Anaximenes of Miletus, Anaxagoras of Clazomenae ... Archelaus of Athens, Pherecydes of Syros, Parmenides of Elea, Diogenes of Apollonia

Anonymous (date uncertain)

Th 569d

CPF I 1*** (102 Thales 1T) (PMilVogliano I 18, col. VI 10-19) (2nd cent. CE)

The story of the tripod

Diegesis of Callimachus’ poems.

When he came to Miletus he gave it to Thales on the grounds that he surpassed the others; but he in turn sent it away to Bias of Priene. [ ...] by him the cup was sent back to Thales. And he dedicated it to Didymean Apollo after twice receiving the prize.

Scholia, chronologically arranged by their approximate date:

Scholia on Apollonius of Rhodes (9th/11th cent. CE The scholia were already constituted in the 2nd cent. BCE but go back to grammatical works of the time of Augustus)692)

Th 570

Water as the first principle.

Scholia on the Argonautica of Apollonius of Rhodes 1.496–498

Thales postulated water as the principle of all things, taking the idea from the poet [Homer] who said “but may you all become water and earth” (Il. 7.99).

Th 571

Thales’ explanation of the flooding of the Nile.

Scholia on the Argonautica of Apollonius of Rhodes 4.267–271a

Thales of Miletus declares that clouds driven by the etesian winds against the mountains of Ethiopia are shattered there.693 But when the winds fall on the sea and unite to oppose the river, the Nile overflows because of the floodwaters that are driven back.

Scholia on Homer (2nd cent. CE)

Thales’ explanation of earthquakes.

Scholia on Iliad 7.455.1–2

“Mighty Earth-shaker.” For according to Thales the earth rides on water, and this is the source of chasms [earthquakes?].694

Scholia on Aratus (2nd/3rd cent. CE)

Th 573695

Thales as astronomer.

Scholia on Aratus’s Phaenomena 26–27

The Bears revolve together which means “run together.” This is why they were named Wains, for there are two of them, the larger of which Nauplius discovered and Thales the Sage the smaller. He says that the smaller one has the image of a dog that belonged to Callisto who hunted together with Artemis, and it died when she did. It has this name because it has the tail of a dog.

Th 574696

Thales as astronomer.

Scholia on Aratus’s Phaenomena 39

The Phoenicians [steer their ships] by the other one – by the small Cynosure. For being small, it turns round in the same place and is easier to spot – not because of its brightness (for it is dim) but because it turns round in the same place. For the other one is larger in its revolution and is not easy to spot because it moves a great deal. The Phoenicians are trusted as being more accurate in things nautical and more experienced than the Greeks, and they look to the smaller one. For Thales, the discoverer of this [constellation], is descended from Phoenicians.

Scholia on Aratus’s Phaenomena 172

And very often is [the name] of those [stars spoken]. Not nameless, he [Aratus] says, are the Hyades, which are found on the forehead of Taurus. Now Thales says that there are two of them, one towards the north and one towards the south, whereas in the Phaethon Euripides says that there are three, Achaeus that there are four, and Musaeus five, while Hippias and Pherecydes say that there are seven.

Scholia on Dionysius Periegetes (turn of the 5thcent. CE)

Th 576

Thales’ relation to Democritus.

Scholia on the Description of the World by Dionysius Periegetes, Life of Dionysius 428.7–9

Who had previously drawn the inhabited world on a tablet? Anaximander was first. Hecataeus of Miletus was second. Third was Democritus, the student of Thales (cf. Th 544). Eudoxus was fourth.

Scholia on Plato (after Proclus, 5th cent. CE)

Th 577697

Thales the Sage.

Scholia on Plato, Timaeus 20d, ter, col.1 (ed. Greene, p. 280)

“Of the seven.” The Sages: Thales, Solon, Chilon, Pittacus, Bias, Teleobulus, Periander [Ti.20d,ter,c2,1]. Their fathers were Examyas ... [Ti.20d,ter,c3,1] Their native lands were Miletus ...

Scholion in Aristotelem (6th cent. CE)

Scholion in Aristotelis de Caelo 4.2.309b29–31

“The same result follows if someone distinguishes these things differently, making things heavier or lighter than others ...” He declares that this is the view of Thales, and he refutes it because it claims that both the dense and the rare have the same matter. For the matter of heavy things and light things is not the same, since in that case a lot of fire would be heavier than a little earth, since they have the same matter and the fire has more.

Thales’ view seems to be plausible, since each element can give rise to another. For if fire is condensed it becomes air, and this [if condensed] becomes water, and this becomes earth; and contrariwise if earth is rarefied it becomes water, then air, then fire. But on this hypothesis nothing will be unqualifiedly light or heavy. For if they have the same matter light and heavy are relatives. This is why this concords with Plato’s view which distinguishes on the basis of magnitude, and many light things will be heavier than a little of something that is dense, and so a lot of fire is heavier than a little earth and nothing is naturally heavy.

Scholia on Plato (after the 6th cent. CE, possibly byHesychius698)

Th 578

Thales’ Phoenician ancestry; Thales as Sage and astronomer; his view on the nature of the soul; water as the first principle; his association with Egypt; his wise sayings.

Scholia on Plato’s Republic 600A1–10

“Thales.” Thales of Miletus, the son of Examyas, was a Phoenician according to Herodotus (cf. Th 12). He was the first to be called a sage. For he discovered that the sun is eclipsed because the moon is beneath it in its course699, and he was the first of the Greeks to recognize the Little Bear and the solstices and to study the size of the sun and its nature, and to claim that even inanimate things somehow possess soul, judging from magnets and amber. He held that water is the principle of the elements, that the cosmos possesses soul and is full of daimons. He was educated in Egypt by the priests. “Know thyself” is his. He died a lonely old man while watching an athletic contest, done in by the heat.

Scholia on Basil (beginning of the 7th to end of the9th Centuries CE700)

Th 579701

Water as the first principle.

Scholia on Basil’s Homilies on the Hexaemeron 1.2 “[Some took refuge in material hypotheses, attributing the cause of the universe] to the elements of the cosmos.”] (PG 29.8A11)

Thales, Heraclitus, Diogenes of Apollonia and their associates, and others who bequeathed the elements as principles of things-that-are: for Thales [bequeathed] water [ ...].

Th 580702

Water as the first principle.

Scholia on Basil’s Homilies on the Hexaemeron 1.2 “Comprise the nature of things visible.’(PG 29.8A13/14)

It is clear that all the Greek sages say that the cosmos and matter consist of more than one thing. Pythagoras calls the elements of principles numbers; Strato, qualities; Alcmeon, oppositions; Anaximander, the infinite; Anaxagoras, homoeomeries; Epicurus, atoms; Diodorus, things without parts; Asclepiades, masses; geometers, limit; Democritus, ideas; Thales, water; Heraclitus, fire; Diogenes, air; Parmenides, earth; Zeno, Empedocles and Plato, fire, water, earth and air, and Aristotle added a fifth, unnamed element. (cf. Th 310).

Scholia on Lucian (11th cent. CE?)

Th 581703

Thales the Sage; his wise sayings.

Scholion on Lucian 1.7

(Phalaris 1) Wise tyrants. He is speaking of Periander, the son of Cypselus, who was one of the Seven Sages of the Greeks. He was tyrant of Corinth, which is next to the Isthmus of the Peloponnese. His saying “Master anger” is inscribed at Delphi. There were sayings of the other Sages too which were also inscribed at Delphi: “Measure is best” (Cleobulus of Lindos), “Know thyself” (Chilon of Lacedaimon), “Nothing in excess” (Pittacus of Mitylene), “Look to the end of a long life” (Solon of Athens), “Most people are bad” (Bias of Priene), “Give a pledge and disaster is at hand” (Thales of Miletus).

Th 582

Thales’ fall into a well.

Scholion on Lucian 29.34.7–8

What is in front of your feet. This is that comment of that Thracian woman with which she cleverly made fun of Thales the natural philosopher.

Scholia on Hesiod (12th cent. CE?)

Th 583

Scholion on Hesiod’s Theogony 116b.14–16

Pherecydes of Syros and Thales of Miletus declare that water is the principle of all things, adopting Hesiod’s statement (cf. Th 286, Th 532).

Scholia on Pindar (before the 13th cent. CE)

Water as the first principle.

Scholion on Pindar’s Olympian Odes1.1d

Water is best (Pindar, Ol. 1.1); for according to Thales water is the principle of all things704.

Scholia on Aristophanes (13th/14th cent. CE)

Th 585

Thales as astronomer.

Scholia vetera on Aristophanes’ Clouds 180.1–2 (Th 17)

Thales. He was one of the Seven Sages, a Milesian by birth, who was the first to make discoveries about events in the sky.

Th 586705

Thales and the crossing of the Halys.

Scholia on Aristophanes’ Clouds 180b

Thales [ ...] [3] for of Croesus [ ...] [6] one of the two to the rear of the army; and when the stream was diminished in this way the army easily crossed the river. He made [ ...] [8] them to cross.

Thales and the crossing of the Halys.

Scholia on Aristophanes’ Clouds 180c

This Thales was one of the Seven Sages. He was a prophet who through mathematical skill caused there to be found for the Halys, when the phosa-ton was unable to cross in the other part of the river.706

Th 588

Thales the Sage, the astronomer, geometer and engineer.

Scholia on Aristophanes’ Clouds 180d. alpha

This Thales was one of the Seven Sages, a Milesian. He was the first among them [the Sages] and he taught about the celestial bodies with reference to the seasons707. He was also the best geometer and a superb engineer.

Th 589

Thales as mathematician and engineer.

Scholia on Aristophanes’ Clouds 180d. beta

This Thales was a Milesian, one of the Seven Sages of old, who was the first to teach mathematics708. He was also an outstanding engineer.

Th 590

Thales as astronomer, geometer, philosopher and Sage.

Scholia on Aristophanes’ Clouds 180e

Thales – the astronomer, the ancient geometer, that is, the philosopher, the sage.

Scholia on Aristophanes (beginning of the 14th cent. CE)

Thales the philosopher and geometer.

Scholia on Aristophanes’ Birds 1009

The man’s a Thales! He says it sarcastically. This Thales is one of the Seven Philosophers and was renowned for his knowledge of geometry.

Scholia on Homer (date uncertain)

Th 592

Thales as astronomer.

Scholia on Homer, Iliad 18.487

And the Bear, which they also call ‘the Wain’ as an alternative name. This one that is called the Great [Bear] and the Wain, because709 it is a constellation formed in the outline of a wagon, and near it is the Little [Bear], which is called “Cynosure” because710 it has its tail bent like a dog’s. Homer does not mention this [constellation] because it was discovered later by Thales of Miletus, one of the Seven Sages.

Pherecydes of Syros

Th 2

Fr. 2 Schibli, cf. Th 498 (Suda Lex. phi 214.1–9)

Th 3

Fr. 58 Schibli, cf. Th 241 (Diog. Laert. 2.46); Th 34 (Arist. Fr. 21.1 Gigon)

Th 4

Fr. 53a Schibli, cf. Th 533 (Tzetz. Chil. 2.869f.)

Th 5

Fr. 53b Schibli, cf. Th 534 (Tzetz. Chil. 11.67f.)

Xenophanes

Th 6

Fr. 21 A 1 DK, cf. Th 243 (Diog. Laert. 9.18.11–12)

Fr. 21 B 19 DK, cf. Th 237 (Diog. Laert. 1.23)

Herodotus

Th 10

Historiae 1.74 (ed. Rosén)

Sim. (solar eclipse) Th 75, Th 77, Th 91, Th 93, Th 105, Th 158, Th 167, Th 203, Th 237 (1.23), Th 244, Th 265, Th 277, Th 300, Th 307, Th 311, Th 355, Th 387, Th 399, Th 407, Th 455, Th 482, Th 487, Th 489, Th 495, Th 525, Th 535, Th 540, Th 578

Hist. 1.75

Sim. (the crossing of the Halys) Th 170, Th 226, Th 237 (1.38), Th 535, Th 545, Th 561, Th 586, Th 587

Hist. 1.170

Sim. (Phoenician ancestry) Th 127, Th 136, Th 202, Th 204, Th 237 (1.22), Th 262, Th 327, Th 495, Th 574, Th 578

Th 13

Hist. 2.20

Sim. (flooding of the Nile) Th 33, Th 82, Th 100, Th 164, Th 237 (1.37), Th 404, Th 476, Th 491, Th 548, Th 560, Th 571 cf. also Lucretius 6.715–23

Democritus

Th 14

Fr. 68 B 115a DK, cf. Th 237 (Diog. Laert. 1.22)

Th 15

Fr. 68 B 115a DK, cf. Th 237 (Diog. Laert. 1.23)

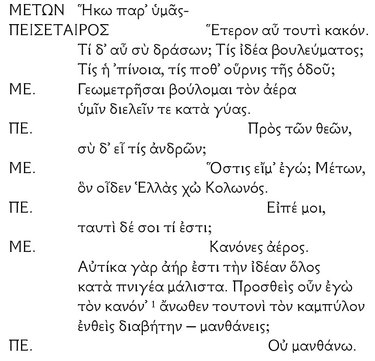

Aristophanes

Th 17

Nubes 168–180 (ed. Wilson)

Th 18

Aves 992–1009 (ed. Wilson)

Sim. (“The man’s a Thales!”) Th 495, Th 591

Plato

Th 19

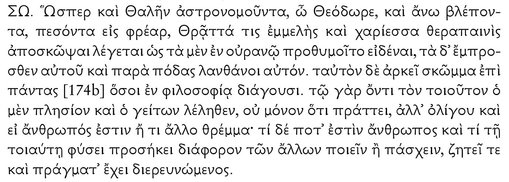

Theaetetus 174A4–B6 (ed. Duke)

Sim. (Thales’ fall into the well) Th 174, Th 210, Th 217, Th 222, Th 237 (1.34), Th 240, Th 251, Th 269, Th 328, Th 361, Th 444, Th 445, Th 446, Th 456, Th 513, Th 518, Th 564 (319), Th 582

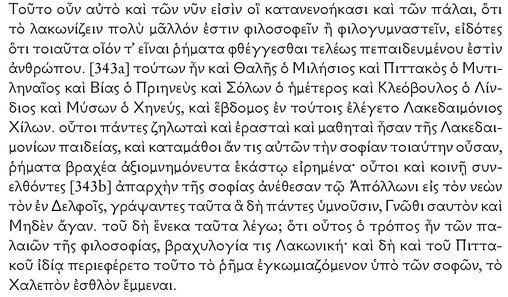

Protagoras 342E4–343B7 (ed. Burnet)

Sim. (Thales, one of the Seven Sages) Th 52, Th 68, Th 70, Th 71, Th 76, Th 81, Th 82, Th 83, Th 87, Th 89, Th 95, Th 127, Th 131, Th 137, Th 171, Th 172, Th 173, Th 176, Th 178, Th 199, Th 210, Th 236, Th 237 (1.22, 34, 40–42) Th 254, Th 264, Th 265, Th 271, Th 294, Th 295, Th 290, Th 304, Th 311, Th 313, Th 314, Th 315, Th 316, Th 329, Th 370, Th 385, Th 386, Th 470, Th 473, Th 476, Th 480, Th 482, Th 485, Th 505, Th 506, Th 509, Th 527, Th 530, Th 533, Th 535, Th 539, Th 540, Th 541, Th 553, Th 560, Th 561, Th 564a, Th 577, Th 581, Th 585, Th 587, Th 588, Th 589, Th 591, Th 592

Th 21

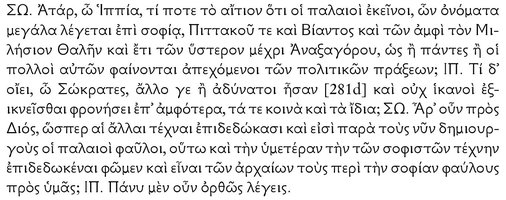

Hippias maior 281C3–D8 (ed. Burnet)

Sim. (political activity) Th 70, Th 228, Th 237 (1.25), Th 454, Th 479, Th 497

Th 22

Res publica 10. 600A4–7 (ed. Burnet)

Epistula 2.311A1–7 (ed. Burnet)

Aristotle

Th 27

Ethica Nicomachea 6.7.1141b2–8 (ed. Bywater)

Sim. (wisdom without practical reason) Th 110, Th 524, Th 531, Th 556 However, cf. Th 237 (Diog. Laert. 1.40) Dicaearchus’s assertion that the Seven Sages (among whom he also names Thales at 1.41 = Th 36) were wise and capable lawgivers

Th 28

Politica 1.11.1259a5–19 (ed. Ross)

Sim. (the olive crop) Th 77, Th 225, Th 237 (1.26)

Th 29

Metaphysica 1.3.983b20–984a7 (ed. Ross)

Sim. (water as the first principle) Th 72, Th 85, Th 87, Th 94, Th 98, Th 116, Th 138, Th 140, Th 142, Th 143, Th 144, Th 145, Th 146, Th 147, Th 181, Th 182, Th 184, Th 187, Th 188, Th 189, Th 190, Th 191, Th 193, Th 196, Th 197, Th 198, Th 206, Th 210, Th 213, Th 215, Th 229, Th 230, Th 232, Th 234, Th 237 (1.27), Th 254, Th 255, Th 259, Th 260, Th 261, Th 271, Th 286, Th 287, Th 288, Th 289, Th 291, Th 292, Th 293, Th 295, Th 309, Th 310, Th 311, Th 312, Th 317, Th 318, Th 319, Th 324, Th 329, Th 338, Th 320 Th 321, Th 343, Th 372, Th 390, Th 392, Th 409, Th 411, Th 414, Th 416, Th 417, Th 418, Th 423, Th 427, Th 429, Th 430, Th 431, Th 436, Th 438, Th 440, Th 447, Th 448, Th 452, Th 453, Th 459, Th 460, Th 462, Th 463, Th 464, Th 465, Th 467, Th 485, Th 499, Th 508, Th 519, Th 525, Th 528, Th 532, Th 537, Th 547, Th 553, Th 558, Th 570, Th 578, Th 579, Th 580, Th 583, Th 584; (the water hypotheses goes back to the first theologians /Homer) Th 94, Th 145, Th 147, Th 187, Th 189, Th 271, Th 286, Th 287, Th 292, Th 329, Th 460, Th 499, Th 532, Th 570, Th 583; (the first sage/philosopher) Th 138, Th 147, Th 189, Th 190, Th 192, Th 218, Th 219, Th 237 (1.24), Th 254, Th 256, Th 257, Th 271, Th 287, Th 292, Th 300, Th 321, Th 322, Th 409, Th 413, Th 419, Th 420, Th 437, Th 442, Th 460, Th 461, Th 473, Th 478, Th 500, Th 501, Th 520c, Th 525, Th 530, Th 541, Th 557, Th 569, Th 578, Th 589

De caelo 2.13.294a28–b6 (ed. Allan)

Sim. (the Earth rests upon water) Th 99, Th 101, Th 163, Th 210, Th 230, Th 387, Th 403, Th 409, Th 425, Th 426, Th 460, Th 526, Th 553, Th 554, Th 555, Th 572

De anima 1.2.405a19–21 (ed. Ross)

Sim. (nature of the soul/magnet) Th 165, Th 221, Th 237 (1.24), Th 301, Th 323, Th 336, Th 360, Th 422, Th 423, Th 442, Th 495, Th 516, Th 525, Th 558, Th 578

Th 32

De an. 1.5.411a7–8

Sim. (all things full of gods/daimons) Th 76, Th 237 (1.27), Th 302, Th 340, Th 424, Th 443; (the cosmos/the universe/ everything has a soul) Th 126, Th 237 (1.27), Th 302, Th 340, Th 424, Th 443

Th 33

De inundacione Nili; s. Th 548.

Fr. 21.1 Gigon = 75 Rose3 [On Poets, book 3], cf. Th 241 (Diog. Laert. 2.46)

Theophrastus

Th 37

583 FHS&G, cf. Th 111 (Plu. Sol. 4.7.80E)

Th 38

225 FHS&G; cf. Th 409 (Simp. in Ph. 23.21–33)

Th 39

According to Simplicius/Theophrastus, Anaximander was the successor and student of Thales.

Chamaeleon (second half of the 4th cent. BCE)

Th 40

Clement reports that according to Chamaeleon, the saying “Know thyself” originated with Thales.

Fr. 2a Wehrli2, cf. Th 200 (Clem. Al. Strom. 1.14.60.3)

Th 40a

An anoymous testimony provides further information regarding the saying “Know thyself.”

Fr. 2b Wehrli2, cf. Th 569a (Anecdota Graeca ed. J. Bekker (1814) I 233, 15)

Th 40b

A papyrus fragment provides further testimony to Chamaeleon’s interest in Thales.

CPF I 1* (29 Chamaeleon 1T), p. 403 (PSI 1093, 31-33 [II.13]), cf. Th 569b

Demetrius of Phaleron (ca. 360–280 BCE)

Th 41

According to the testimony of Demetrius, that Thales was called the first Sage during the archonship of Damasias (582–580 BCE) when the Seven Sages were first named.

Fr. 149 Wehrli2, cf. Th 237 (Diog. Laert. 1.22)

Th 42

Stobaeus quotes many sayings of Thales, which were collected by Demetrius. Fr. 114 Wehrli2, cf. Th 362 (Stob. Ecl. 3.1.172)

Eudemus (born before 350 BCE)

Th 43

Proclus reports that Eudemus attributed the second congruence theorem to Thales, judging by the way Thales is said to have calculated the distance of ships at sea.

Fr. 134 Wehrli712, cf. Th 384 (Procl. in Euc. 352.14–18)

Th 44

Proclus reports that according to Eudemus Thales discovered, but did not prove, the theorem that the opposite angles made by two intersecting straight lines are equal.

Fr. 135 Wehrli712, cf. Th 383 (Procl. in Euc. 299.1–5)

Th 45

Clement reports the testimony of Eudemus that Thales predicted the solar eclipse that took place during the battle of the Medes and the Lydians, which had already been reported by Herodotus.

Fr. 143 Wehrli712, cf. Th 203 (Clem. Al. Strom. 1.14.65.1)

Th 46

Diogenes Laertius refers to the report in Eudemus that Thales was the first to pursue astronomy and to predict solar eclipses and solstices.

Fr. 144 Wehrli712, cf. Th 237 (Diog. Laert. 1.23)

Th 47

According to Theon, who refers to Dercyllides, Eudemus says that Thales was the first to discover solar eclipses and the inequality of the times between the solstices.

Fr. 135 Wehrli712, cf. Th 93 (Heron Def. 138.11, cf. Th 167 (Theon Sm. 198 Hiller)

Duris of Samos (4th/3rd cent. BCE)

Th 48

Diogenes Laertius reports that according to Duris and other sources Thales was the son of Examyas and Cleobuline and belonged to the Thelidae, who were Phoenicians.

FGrHist II A 76 F 74, cf. Th 237 (Diog. Laert. 1.22)

Phoenix of Colophon (4th/3rd cent. BCE)

Th 49

Athenaeus transmits a poetic fragment of Phoenix, according to whom Thales received a golden bowl for being the best of men and the most outstanding astronomer.

Fr. 5, 234 ed. Powell, cf. Th 235 (Ath. Deipn. 11.91.495D)

Leandr(i)us (= Maeandrius?, early Hellenisticperiod)

Th 50

Clement and Theodoret report on the evidence of Leandrius and Herodotus that Thales was a Phoenician.

FGrHist III B 491–2 F 17, cf. Th 202 (Clem. Al. Strom. 1.14.62.1–63.2), cf. Th 327 (Theod. Gr. aff. cur. 1.24)

Th 51

To Leandrius is due a variant on the story of the tripod on which, according to Diogenes Laertius, Callimachus relied: a bowl was given to Thales, and after making the round of the Seven Sages came back to him, and he sent it to Didymean Apollo.

FGrHist III B 491–2 F 18, cf. Th 237 (Diog. Laert. 1.28–29)

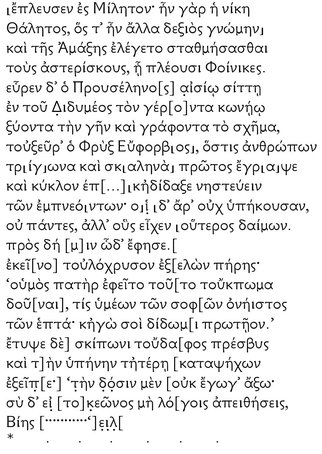

Callimachus (between 320 and 302–after 246 BCE)

Th 52

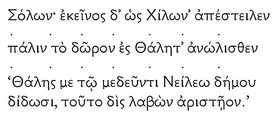

Thales the Sage; variant on the story of the tripod.

Iambus 1 tells among other things how Amphalaces of Arcadia fulfilled the instructions of his dying father to bring a golden cup to the best of the Seven Sages. From Thales the cup went to Bias, and after making the round of the Seven Sages returned again to Thales, who dedicated the cup to Apollo of Didyma with an inscription.713

Iambus 1.52–77

He sailed to Miletus, for the victory belonged

to Thales. In general he was clever in his judgment,

and in particular it was said that he mapped the little stars

of the Wain,712 by which the Phoenicians sail.

And the Pre-mooner714 by happy chance715 found

the old man in the temple of Didymean716 [Apollo], scratching

the earth with a staff, constructing the figure

discovered by Euphorbus717 the Phrygian, who

was the first to construct triangles and scalenes

and the circle ... and taught men to abstain from eating

living things ... but they did not obey him –

not all, but those who were possessed by the evil daimon.718

To him he said thus ...

after drawing from his bag the object of solid gold:

‘My father charged me to present this cup

to the most useful719 of you Seven Sages;

and I give the prize720 to you.’

And the old man struck the ground with his stick,

and stroking his beard with his other hand,

answered: ‘I will not accept the gift;

but if you are not going to disobey your father’s words,

Bias ...

Solon. And he sent it to Chilon ...

and the gift returned to Thales again ....

‘To the protector of the people of Neleus721 Thales dedicates me –

this prize for excellence, which he twice received.’

Sim. (constellations/discoverer of the Great/Little Bear) Th 136, Th 178, Th 231, Th 235, Th 237 (1.23), Th 543, Th 573, Th 574, Th 578, Th 592; (Thales’ prize/story of the tripod) Th 83, Th 95, Th 111, Th 235, Th 237 (1.27ff.), Th 295, Th 375, Th 379, Th 504, Th 509, Th 536, Th 539; (Thales, one of the Seven Sages) Th 20 (q.v.)

Timon of Phlious (ca. 320/15–230/25 BCE)

Th 53

Diogenes Laertius quotes a verse of Timon as evidence that Thales was an astronomer.

Fr. 797 Suppl. Hell. (Diels Fr. B 23), cf. Th 237 (Diog. Laert. 1.34)

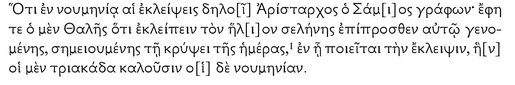

Aristarchus of Samos (ca. 310–230 BCE)

Th 54

A papyrus commentary on Homer’s Odyssey from the first cent. BCE contains a quotation from Aristarchus with information about Thales’ explanation of solar eclipses.

P. Oxy. 53.3710 col. 2.36–43 (ed. Bowen/Goldstein), cf. Th 91 (Comm. on Od. 20.156)

Lobon of Argos (3rd cent. BCE)

Th 55

Diogenes Laertius says that Lobon reported that Thales’ writings consist of verses (Th 237 [1.34]). Moreover, Diogenes Laertius reports the inscription on the base of a statue of Thales, which rates him as the most noteworthy astronomer and which goes back to Lobon (ibid.).

F. 509 Suppl. Hell., cf. Th 237 (Diog. Laert. 1.34 = AP 7.83)

Th 56

Lobon also quotes a grave inscription which celebrates Thales’ fame.

F. 510 Suppl. Hell., cf. Th 237 (Diog. Laert. 1.39 = AP 7.84)

Hermippus of Smyrna (“the Callimachean,” 3rd cent. BCE)

Th 57

Plutarch reports a conversation between Solon and Thales in which, on the occasion of the falsely reported death of Solon’s son, Thales produces an argument for his own childlessness, a story which according to Plutarch. citing the authority of Hermippus, goes back ultimately to Pataecus.

Fr. 10 Wehrli = FGrHist cont. IV A 3 1026 F 17, cf. Th 112 (Plu. Sol. 6.6.4–7.3.81D)

Th 58

Diogenes Laertius says that Hermippus attributed to Thales the saying sometimes ascribed to Socrates, that he is grateful for three things: that he was born a human, a man, and a Greek.

Fr. 11 Wehrli = FGrHist cont. IV A 3 1026 F 13, cf. Th 237 (Diog. Laert. 1.33)

Th 59

According to Diogenes Laertius Hermippus names Thales as one of seventeen men variously listed among the Seven Sages.

Fr. 6 Wehrli = FGrHist cont. IV A 3 1026 F 10, cf. Th 237 (Diog. Laert. 1.42)

Hieronymus of Rhodes (ca. 290–230 BCE)

Th 60

According to Diogenes Laertius Hieronymus reports that Thales, in order to prove that it is easy to become wealthy, when he foresaw that there would be a large olive crop, rented the olive presses and made a huge profit.

Fr. 39 Wehrli712, cf. Th 237 (Diog. Laert. 1.26)

Th 61

Diogenes Laertius refers to Hieronymus as a source for the story that Thales measured the height of the pyramids by the length of their shadow.

Fr. 40 Wehrli712, cf. Th 237 (Diog. Laert. 1.27)

Titus Maccius Plautus (born ca. 250 BCE)

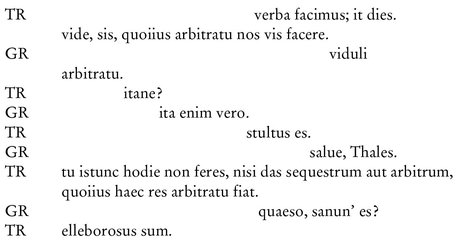

Th 62

Thales the proverbial genius.

In Roman comedy as well as Greek (see above Aristophanes, Th 18) Thales could be used as a prototype of a clever person. This is how the slave Tyndarus in The Captives praises his master Philocrates for his ability to imitate a slave:

The Captives 274–276

Well done, my boy! I wouldn’t give a talent to buy Thales of Miletus. In comparison with this man’s wisdom he was just an amateur. How cleverly he’s altered his speech to sound like a servant!722

Th 63

Thales the proverbial genius.

The Rope 997–1006

Tranchalio What color is it?

Gripus The ones they catch that have this color are tiny. Others have red skins, but they’re big. There are black ones too.

Tranch. I know. And I think that you will turn into a trunkfish yourself if you don’t watch out! First you will have red skin and then black.

Gr. What a cursed mess this is that I’ve got into today!

Tranch. These are just empty words. Time’s passing. Just tell me who do you want to decide this for us.

Gr. Trunk.

Tranch. Come again?

Gr. That’s right.

Tranch. You’re an idiot!723

Gr. Hello, there, you Thales.

Tranch. You will not carry that off today without appointing some trustee or judge by whose judgment this case will be decided.

Gr. See here, are you sane?

Tranch. No, I’m out of my mind!

Th 64724

Thales the proverbial genius.

Bacchides 120–124

Lydus Is there some god Sweetysweetiness?

Pistoclerus Didn’t you ever suppose there was? You’re a barbarian, Lydus! And I thought you were so much wiser than Thales, but there you are –dumber than a barbarian babe in arms – at your age not knowing the names of the gods!

Hippobotus (active at the end of the 3rd cent. BCE)

Th 65

According to Diogenes Laertius, Thales was listed as a Sage in Hippobotus’s catalogue of philosophers.

Fr. 6 Gigante, cf. Th 237 (Diog. Laert. 1.42)

Inscription in the Gymnasium of Tauromenium

(ed. Blanck)

Sim. (Anaximander pupil/associate of Thales) Th 71, Th 80, Th 81, Th 134, Th 140, Th 143, Th 202, Th 211, Th 236, Th 239, Th 241, Th 265, Th 300, Th 311, Th 329, Th 391, Th 410, Th 431, Th 482a, Th 494, Th 540, Th 544

Inscription in the Gymnasium of Tauromenium (2nd cent. BCE)

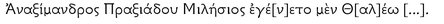

Th 65a (= Ar 23)

Thales’ association with Anaximander.

Inscription, probably from a list of the inventory of the library of the Gymnasium of Tauromenium.

Anaximander of Miletus, the son of Praxiades. He was the [student, follower or the like] of Thales.

Sosicrates (flourished at the beginning of the 2nd cent. BCE)

Th 66

According to Diogenes Laertius Sosicrates said that Thales was ninety years old when he died.

FHG IV 501.10, cf. Th 237 (Diog. Laert. 1.38)

Apollodorus (ca. 180–ca. 110 BCE)

Th 67

According to Diogenes Laertius, Apollodorus reported that Thales was born in the first year of the thirty-ninth Olympiad (624 BCE).

FGrHist II B 244 F 28, cf. Th 237 (Diog. Laert. 1.37)

Marcus Terentius Varro (116–27 BCE)

Th 69

Thales’ views on the origin of animals.

Res Rusticae 2.1.3 (ed. Flach)

Since I had accepted the terms and the first parts were mine [ ...] I said, “Therefore, since both humans and beasts must always have existed by nature – for whether there was some beginning of the generation of animals, as Thales of Miletus thought, and Zeno of Citium, or to the contrary there was no beginning of them as Pythagoras of Samos believed and Aristotle of Stagira – human life must have descended gradually from the earliest memory to the present, as Dicaearchus writes, and that the earliest stage was natural, when humans lived on things which the unviolated earth brought forth 725,726 voluntarily.

Marcus Tullius Cicero (106–43 BCE)

Th 70

Thales the Sage.

Cicero praises universal education as the foundation of eloquence.

On the Orator 3.137

But to bring my discussion back to the Greeks, who cannot be omitted at least in this kind of conversation – for just as we must look to our own people for examples of virtue, so we must look to them [the Greeks] for examples of learning – it is said that at one time there were seven persons who were both considered and called Sages. All of them except Thales of Miletus were the heads of their cities.727

Th 71

Thales the Sage; water as the first principle; Thales and Anaximander. There is great disagreement about the material principles of all things.

Lucullus 118

The first was Thales, the one of the Seven to whom the remaining six are said to have yielded the first place. He said that all things are made of water. But in this he did not persuade Anaximander, his fellow citizen and associate; he [Anaximander] said that there exists an infinitude of nature from which all things are generated. Afterwards his pupil Anaximenes held that air is infinite, but the things that originate from it are determinate; that earth, water and fire are generated, and then everything else [is generated] from them.

Th 72

Water as the first principle; his theological views.

In De Natura Deorum 1.25–42, the Epicurean Velleius sets out twenty-seven different theological views beginning with Thales and extending to the second cent. BCE728

Sim. (nature of god]) Th 73, Th 78, Th 90, Th 96, Th 121, Th 149, Th 150, Th 186, Th 207, Th 210, Th 216, Th 218, Th 219, Th 220, Th 229, Th 254, Th 258, Th 272, Th 338, Th 339, Th 340, Th 375, Th 376, Th 393, Th 424, Th 443, Th 458, Th 475, Th 485, Th 499 (however, cf. Th 311); (water as the first principle) Th 29 (q.v.)

On the Nature of the Gods 1.25–26

For Thales of Miletus, who was the first to investigate these matters,729 said that the origin of things is water, and that god is the intelligence that fashions everything from water (supposing that there can be gods who lack sensation). And why did he attach intelligence to water if intelligence can exist by itself730 without a body? Further, Anaximander’s view is that the gods are born, arising and perishing at great distances,731 732 and that they are countless worlds. [26] But how can we conceive of a god that is not everlasting? Afterwards, Anaximenes made air a god and held that it is generated and is vast and infinite733 and always in motion; as if air, lacking any definite form, could be a god – especially since god must not just have any appearance but the most beautiful one – or as if everything that has a beginning must not necessarily be mortal.

Th 73

Thales’ theological views.

On the Nature of the Gods 1.91–92

And indeed you have fully recounted from memory the views of the philosophers on the nature of the gods, back to Thales of Miletus [Th 72], so I am delighted to express my admiration for such great knowledge in a Roman. [92] But do all of them who have decreed that there can be a god without hands and feet seem to you to be mad? When you contemplate the usefulness and suitability [to human activities] there is in human limbs, does even this not move you to conclude that the gods do not lack human limbs?734

Th 74

Thales as inventor of the celestial sphere.

In the first book of Cicero’s De Re Publica, Lucius Furius Philus, one of the participants in the conversation, reports how once upon a time in the house of Marcus Marcellus, Sulpicius Gallus had explained the phenomenon of a double sun with the help of the celestial sphere of Archimedes, which Marcellus’s grandfather had brought from Syracuse.

De Re Publica 1.21–22

Although I had very often heard mention of this celestial globe because of Archimedes’ fame, I did not admire its actual appearance very much; for the other one, which the same Marcellus placed in the temple of Virtus and which was also constructed by Archimedes, is more beautiful as well as more highly esteemed among the people. [22] But when Gallus began to give a very learned account of the device, I concluded that the famous Sicilian had a greater share of genius than it would seem that human nature could produce. For Gallus said that the other kind of globe, which was solid, not hollow, was an early invention and that Thales of Miletus was the first to fashion that kind of globe,735 and later Eudoxus of Cnidus (a student of Plato, he claimed) marked it with the stars which are fixed in the heaven. [ ...] But this [newer] kind of globe, [he said], on which are found the motions of the sun, the moon and the five stars which are called wanderers, or, as we might say, rovers, – which could not have been marked out on the other kind of globe, which was solid [ ...]

Th 75

Thales’ explanation of eclipses.

De Re Publica 1.25

For at that time this theory was new and unknown – that the sun is eclipsed by the interposition of the moon – a fact which Thales of Miletus is said to have been the first to observe.

Th 76

Thales the Sage.

De Legibus 2.26

For this view [that the gods should have temples in cities] promotes a religious feeling736 that is useful to cities, if indeed it was well said by Pythagoras, a most learned man, that piety and religious feeling are in our minds737 above all when we are performing religious rites, and in the saying of Thales, the wisest of the Seven, that people should believe that everything they see is full of gods, because then everyone would be more pure, as happens when they are in the holiest shrines. For there is a view that the gods can appear to our eyes as well as to our minds.

Th 77

Thales’ practical wisdom; the story of the olive crop.

On Divination 1.111–112

Rare is that class of men who call themselves away from the body and are carried away by a concern and interest in the knowledge of things divine. The auguries of these men are due not to a divine impulse but to human reason. On the basis of [their knowledge of] nature they predict what will be, for example, floods and a future conflagration of heaven and earth. Some who are versed in statesmanship, as we have heard is the case with Solon of Athens, foresee the rise of tyranny far in advance. We738 can call these men prudent, that is, provident, but in no way can we call them divine,739 any more than Thales of Miletus, who, to refute his detractors and show that even a philosopher can make money if it is to his advantage to do so, is said to have purchased the entire olive crop in the plain of Miletus before [the olive trees] came into bloom. (112) Perhaps he had noticed because of some knowledge that there would be an abundant crop of olives. Moreover, he is said to have been the first to predict the eclipse of the sun that took place in the reign of Astyages.

Th 78

Thales as natural philosopher.

On Divination 2.58

It was reported to the Senate that it had rained blood, that the river Atratus had flowed with blood and that statues of the gods had dripped with sweat. Surely you do not think that Thales, Anaxagoras, or any other natural philosopher would have believed such reports. Blood and sweat come only from a body. A discoloration produced by the contact of earth [with water] can be very like blood; and the moisture that forms on the outside of objects, as we see on plastered walls when the south wind blows, seems to resemble sweat.

Nicolaus of Damascus (born ca. 64 BCE)

Th 79

In an extract from the Histories of Nicolaus of Damascus preserved by Constantinus Porphyrogenitus, it is reported how Croesus was rescued from being burned on the pyre by a thunderstorm which Thales had predicted. FGrHist II A 90 F 68, cf. Th 503 (Const. Porph. Virt. 1.348.21–22)

Strabo (before 62 BCE–between 23 and 25 CE)

Th 80

Thales’ association with Anaximander.

Geographica 1.1.11

It is clear that his [Homer’s] successors too were men of importance and they were familiar with philosophy.740 Eratosthenes declares that the first two [geographers] who came after Homer were Anaximander, an acquaintance and fellow citizen of Thales, and Hecataeus of Miletus; that the former published the first geographical map, and that Hecataeus left behind him a work on geography,741 a work believed to be his on the basis of his other writings.742

Th 81

Thales the Sage and natural philosopher; Thales and Anaximander.

Geographica 14.1.7

Memorable men were born at Miletus: Thales, one of the Seven Sages, the first among the Greeks to begin the study of natural philosophy and mathematics, and his student Anaximander, and in turn the student of the latter, Anaximenes, and Hecataeus as well.

Diodorus Siculus (before 60–after 36 BCE)

Th 82

Thales the Sage; his explanation of the flooding of the Nile.

Bibliotheca Historica 1.38.1–2

Now that we have discussed its [the Nile’s] sources and its course we shall attempt to set out the causes of its rising. [1.38.2] Thales743, who is named as one of the Seven Sages, says that when the etesian winds blow against the mouths of the river they hinder the stream from entering the sea and that this is why it rises and floods Egypt, which is a low and level plain.

Th 83744

Thales the Sage; the story of the tripod.

Bibliotheca Historica 9.3.3

Desiring to follow the injunction of the oracle, the Milesians wanted to award the prize to Thales of Miletus. But he declared that he was not the wisest of all and advised them to send it someone else who was wiser. In this way the rest of the Seven Sages rejected the tripod too, and it was given to Solon, who was thought superior to all men both in wisdom and in understanding. But he advised them to dedicate it to Apollo, since he was wiser than all.

Didymus Chalcenterus (second half of the 1st cent. BCE)

Th 84

According to Clement, Didymus attributed the saying “Give a pledge and disaster is at hand” to Thales.

Symp. Fr. 4 Schmidt, cf. Th 201 (Clem. Al. Strom. 1.14.51.2–3)

Marcus Vitruvius Pollio(end of the 1st cent. BCE)

Th 85745

Water as the first principle.

On Architecture 2.2.1

Thales declared that water is the first principle of all things. Heraclitus of Ephesus (who because of the obscurity of his writings was called Obscure by the Greeks), fire; Democritus, and Epicurus who followed him, atoms, which our writers have called uncuttable bodies, and some call them indivisible.

Th 86746

Thales as author and natural philosopher.

On Architecture 7, Preface 1–2

Our predecessors, wisely and with advantage, instituted the practice of passing down their thoughts to posterity in the form of treatises, so that they should not perish, but being improved over time and published as books, they should gradually attain over a lengthy period of time the highest refinement of learning. For this reason we owe them not a small debt of gratitude but an infinite amount, because they did not pass over them in jealous silence, but assured that their views on all kinds of things would be recorded in written works.

[2] If they had not done so, we could not have known what happened at Troy, or the views on nature held by Thales, Democritus, Anaxagoras, Xenophanes, and the rest of the natural philosophers, or the goals of human conduct determined by Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, Zeno, Epicurus, and other philosophers, nor would the deeds and purposes of Croesus, Alexander, Darius, and other monarchs have been known if our predecessors in their records and collections of opinions had not gathered all their precepts and published them in treatises for posterity for all to remember.

Th 87747

Water as the first principle.

On Architecture 8, Preface 1

Of the Seven Sages Thales of Miletus declared that the principle of all things is water; Heraclitus, fire; the priests of the Magi, water and fire; Euripides, the pupil of Anaxagoras, whom the Athenians called the philosopher of the stage, air and earth [ ...].

Th 88

Thales as natural philosopher.

On Architecture 9.6.3

Thales of Miletus, Anaxagoras of Clazomenae, Pythagoras of Samos, Xenophanes of Colophon and Democritus of Abdera left elaborate theories in natural philosophy about the entities that control nature, and how they work.

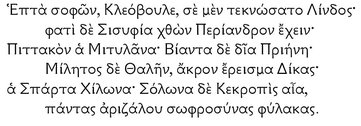

Anonymous(Antipater of Thessalonica?, born ca. 1 CE)

Th 89

Thales the Sage; his wise sayings.

Antipater is accepted as the author of the poem about the Seven Sages that is transmitted in the Scholia on Plato’s Protagoras 343A (Greene) and is included in the Palatine Anthology.

Palatine Anthology 9.366

I will say in verse the cities, names, and sayings of the Seven Sages.

Cleobulus of Lindos said “Measure is best.”

Chilon in the valley of Lacedaimon said “Know thyself.”

Periander, who lived in Corinth, “Master anger.”

Pittacus, from Mytilene by birth, “Nothing in excess.”

Solon, in holy Athens, “Look to the end of life.”

Bias of Priene declared “Most men are evil.”

Thales of Miletus pronounced “Avoid pledging.”

Corpus Hermeticum (1st–3rd Centuries CE)

Th 90

Thales the Sage; his wise sayings.

Fragment 28.1

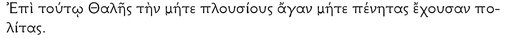

When asked what is the oldest of existing things, Thales answered “God, for he is unbegotten” (cf. Th 121; Th 237 [Diog. Laert. 1.35]; Th 339; Th 564 [320a])

Commentary on Homer, Odyssey, book 20 (1st cent. CE?)748

Th 91

Thales’ explanation of eclipses.

Commentary on 20.156, Oxyrhynchus Papyrus 53.3710 col. 2.36–43 Aristarchus of Samos (Th 54) shows that eclipses occur at the new moon, writing: “Thales said that the sun is eclipsed when the moon comes to be in front of it, and that the day on which it causes the eclipse is marked by its concealment. This is the day that some people call the thirtieth and others call the new moon.749”

Hero (? 1st cent. CE)

Th 92750

Thales and geometry.

Definitions 1.36.1751

Geometry was first discovered by the Egyptians. Thales brought it to the Greeks. After Thales, Mamertius, the brother of the poet Stesichorus, and Hippias of Elis, and afterwards Pythagoras, reflecting on its principles from above and investigating its theorems immaterially and intelligibly, and after him Anaxagoras, Plato, Oenopides of Chios, Theodorus of Cyrene, and Hippocrates who lived before Plato.

Th 93

Thales views on eclipses; his cosmology.

Definitions 1.38.11

Who discovered what in mathematics752? In his work Astronomy753 Eudemus (Th 47) reports that Oenopides754 was the first to discover the zodiac belt755 and the period of the great year. Thales [was the first to discover] the eclipse of the sun and that its path between the solstices is not equal.756 757 Anaximander, that the earth is aloft and in motion758 around the center of the cosmos. Anaximenes, that the moon has its light from the sun and how it is eclipsed.

Heraclitus the Stoic (1st cent. CE, Augustus’s reign–Nero’s reign)

Th 94

Water as the first principle.

Homeric Questions (= Allegories) 22.3–8

They agree that Thales of Miletus was the first to hold that water is the cosmogonic element of all things. For the moist nature is easily fashioned to produce all things and take on many forms. [4] For when part of it turns to vapor it becomes air, and the finest part [of the air] is kindled and from air it becomes aether, and when water settles and changes into mud it turns into earth. [5] This is why Thales declared that of the quartet of elements, water is the element on the grounds that it is the most causal. [6] Now who gave birth to this doctrine? Not Homer, who said [Il. 14.246], “Okeanos who is the origin of all things,” [7] ... [8] But Anaxagoras of Clazomenae, who is known as belonging to the succession of Thales, joined earth to water as a second element [ ...].

Valerius Maximus (first half of the 1st cent. CE)

Th 95759

Thales the Sage; the story of the tripod.

Memorable Deeds and Words 4.1.7 (de externis)

Mentioning this person [Pittacus] prompts me to speak of the modesty of the Seven Sages. In the area of Miletus it happened that when some fishermen were hauling in their net someone had bought their catch. A golden Delphic table of great weight was pulled out from it and there arose a dispute, with the fishermen asserting that they had sold a catch of fish, the other that he had bought the luck of the haul. Because of the unusual nature of the matter and the amount of money involved the controversy was brought to the entire population of the city, and it was decided to consult Apollo at Delphi as to who should be awarded the table. The god responded that it should be given to him who excelled all others in wisdom, in the following words: “Who is the first of all in wisdom? I declare the tripod to be his.” Then the Milesians by consensus gave the table to Thales. He yielded it to Bias, Bias to Pittacus, Pittacus then to another and so on through the entire round of the Seven Sages until finally it came to Solon, who transferred the title of greatest wisdom and the prize to Apollo himself.

Sim. (Thales’ prize/story of the tripod) Th 52 (q.v.); (Thales, one of the Seven Sages) Th 20 (q.v.)

Th 96

Thales the Sage; his wise sayings.

Memorable Words and Deeds 7.2.8 (de externis)

Thales too [said something] wonderful. Asked whether the gods fail to notice people’s actions, he said: “Not even their thoughts” (cf. Th 207; Th 237 [Diog. Laert. 1.36]; Th 564 [316]), so that we should wish to have not only our hands clean but our minds as well, if we believed that a celestial power is present when we have secret thoughts.

Aristocles of Messene(first half of the 1st cent. CE)760

Th 97

Eusebius cites Aristocles’ De Philosophia for the relation between Plato’s philosophy and that of the natural philosophers (including Thales).

Fr. 1 Mullach (FPhG III 206) = Fr. 1 Heiland. Citation from the seventh book of Aristocles’ On Philosophy, cf. Th 268 (Eus. PE 11.3.1)

Lucius Annaeus Seneca (ca. 1761–65 CE)

Th 98

Water as the first principle.

Natural Questions 3.13.1

I will add, as Thales says, “it is the most powerful element.” He thinks it was the first and that all things have arisen from it.

Th 99

Thales’ explanation of earthquakes.

Natural Questions 3.14.1–2

The following view of Thales is silly. He says that the world is held up by water and rides on it like a ship, and because of its mobility, when it is said to tremble it is actually moving with the waves. “Therefore It is not surprising if there is plenty of moisture to make rivers flow since the whole earth is in moisture.” [2] Reject this crude and outdated view. Nor is there reason to believe that water enters this world through cracks and forms bilge.

Th 100

Thales’ explanation of the flooding of the Nile.

Natural Questions 4A.2.22

If you believe Thales, the etesian winds hinder the Nile as it descends and hold back its current by driving the sea against its mouths. Beaten back in this way, it runs back on itself and does not actually increase; but since it is kept from flowing out it stops and, piling up upon itself, it soon bursts forth wherever it can.

Th 101

Thales’ explanation of earthquakes.

Natural Questions 6.6.1–2

That the cause [of earthquakes] is found in water is stated by more than one person and more than one account is given. Thales of Miletus judges that the whole earth is carried and floats upon moisture that lies underneath it, whether you call it the ocean, the great sea, or water of a different nature that is still uncompounded and simply the moist element. “On this water the earth is supported,” he says, “as a big heavy ship is supported by the water which it presses down upon.” [2] It is superfluous to give the reasons why he thinks that the heaviest part of the world cannot be carried by breath, which is so thin and mobile;762 for the present subject is not the earth’s location but its motion. He offers this argument that water is the cause of the earth’s agitation: in every major earthquake new springs usually burst forth, as it also happens that ships take on water if they tilt and lean to one side, and if they are pressed down too much when they are carrying excessive weight, either the water overwhelms them or it rises on the right and left sides more than usual.

Pamphila (mid-1st cent. CE)

Th 102

According to Diogenes Laertius, Pamphile reports that Thales learned geometry from the Egyptians, that he was the first to inscribe a right-angled triangle in a circle and that he sacrificed an ox.

FHG III 520, cf. Th 237 (Diog. Laert. 1.24)

Pomponius Mela (mid-1st cent. CE)

Th 103763

Thales as citizen of Miletus.

De Chorographia 1.86

After the Gulf of Basilicus, the coast of Ionia bends and twists, and when it begins its first turn after the promontory of Poseidon it enfolds the oracle of Apollo that was once called Branchiadae and now Didyma; Miletus, once the first city of all Ionia in the arts of war and peace, the fatherland of Thales the astronomer, Timotheus the musician and Anaximander the natural philosopher, and deservedly renowned for the celebrated abilities of other citizens as well, wherever they speak of Ionia.

Gaius Plinius Secundus (23/4–79 CE)

Th 104764

Thales as author.

Natural History 1.1

Foreign sources [of N.H. book 18, On Agriculture] [ ...] Dionysius’s translation of Mago, Diophanes’ summary of Dionysius, Thales, Eudoxus, Philippus, Calippus, Dositheus, Parmeniscus, Meton, Crito, Oenopides, Conon. [ ...]

Th 105

Thales’ prediction of an eclipse.

Natural History 2.53

Among the Greeks the first of all to investigate [solar eclipses] was Thales of Miletus, who in the fourth year of the forty-eighth Olympiad (585 BCE) predicted the eclipse of the sun that occurred during the reign of King Alyattes, in the 170th year after the foundation of Rome.

Th 106

Thales as astronomer.

Natural History 18.212–13765

I will give one instance of disagreement as an example of people from the same country766 who have differing views: Hesiod – for there is extant a work on astronomy that bears his name – relates that the morning setting of the Pleiades occurs when the autumnal equinox takes place, whereas Thales puts it on the twenty-fifth day after the equinox,767 Anaximander on the thirty-first, Euctemon768 on the forty-fourth, and Eudoxus769 on the forty-eighth.

Th 107

Thales and geometry.

Natural History 36.82

Thales of Miletus discovered a method of finding out their [the Pyramids’] height and of making any similar measurement, by measuring the shadow at the time when a body’s shadow is equal to its length.

Josephus (37/8–? 100 CE)

Th 108

Thales as astronomer and author; his association with Egypt.

Against Apion 1.2

But as for the Greeks who were the first to philosophize about matters celestial and divine, such as Pherecydes of Syros, Pythagoras and Thales, everyone agrees unanimously that they wrote a few things after becoming students of the Egyptians and Chaldeans, and that these writings seem to the Greeks to be the most ancient of all, but it is hard for anyone to believe that they were written by those men.

Plutarch (ca. 45–before 125 CE)

Th 109

Thales as businessman.

At the beginning of his Life of Solon, Plutarch asserts that Solon engaged in trade, since in earlier times such an occupation and its associated travels were not at all objectionable.

Solon 2.8.1–4.79E

They say that Thales engaged in commerce, and so did Hippocrates the mathematician; and Plato covered the expenses of his travels by selling oil in Egypt.

Th 110

Thales as Sage; his theoretical interests.

In view of Solon’s limited knowledge of natural philosophy Plutarch comes to the following general assessment:

Solon 3.8.1–3.80B–C

And in general, it seems that Thales was alone in his time in extending his wisdom beyond practical necessity to contemplation; the rest got their reputation for wisdom from their success as statesmen.

Th 111

Thales the Sage; the story of the tripod.

Here too is told the story of the tripod (cf. especially Th 237 [1.27 ff.]).

Solon 4.7.1–4.80E

Theophrastus, however, says (Th 37) that the tripod was first sent to Priene for Bias, and next it was sent by Bias to Miletus for Thales, and so passed through all of them until once more it came around to Bias, and in the end it was dispatched to Delphi.770

Th 112

Thales’ views on marriage and family.

In the sixth chapter (cf. Solon 5.1–2) Plutarch speaks of a visit of Solon to Thales in Miletus. Solon asked why Thales had no wife or children. At first Thales did not answer, but a few days later he got a stranger to tell Solon that he had returned from a trip to Athens. When Solon asked for news the stranger finally said that Solon’s son had died. Thales took Solon, who was extremely distressed, by the hand and laughingly said:

Solon 6.6.4–7.3.81D

“This, Solon”, [Thales] said, “is what keeps me from marriage and having children; it ruins even you, who are the sturdiest of men. But [6.7] don’t worry about these words because they are not true.” This is what Hermippus 771 (Th 57) says Pataecus reported, he who insisted that he had Aesop’s soul.

Th 113772

Thales’ views on marriage and family.

Solon 7.1.1–3.1.81D–E

Anyone who refuses to pursue what he should aim to acquire out of fear of losing it is peculiar and unworthy; for anyone who thinks like this cannot be contented with wealth, honor or wisdom, [2] in fear that he may be deprived of them. We even see cases where virtue, the most important and pleasing thing to possess, is lost through sickness and drugs. Even if Thales himself did not marry, he still would have had grounds to fear, unless he also avoided having friends, or relatives, or a country. On the contrary, he had an adopted son, [3] Cybisthus, his sister’s son, as they say.

Th 114

Thales’ practical wisdom.

Plutarch refers to a prophecy of Epimenides of Crete (counted by some as one of the Seven Sages) about the Athenian fortress at Munychia: the Athenians would destroy this place if they knew how much misfortune it would bring in the future.773

Solon 12.11.1–12.1.84F

They say that Thales made a similar conjecture. He gave instructions for his burial in an unpretentious and neglected place in the territory of Miletus, predicting that someday that spot would be the market place of the Milesians.

Th 115774

Thales’ association with Egypt.

Isis and Osiris 9–10.354D–E

So great, then, was the reverence of the Egyptians in their wisdom about religion. The wisest of the Greeks [354E] also testify to this: Solon, Thales, Plato, Eudoxus and Pythagoras, who all went to Egypt and associated with the priests.

Th 116

Water as the first principle.

From Plutarch’s writing on the meaning of the Egyptian myth of Isis and Osiris we learn many peculiarities of Egyptian religion and culture.

Isis and Osiris 34.365C–D

They [the Egyptians] think that Homer775 too, like Thales, [364D] posited water as the principle and origin of all things, after learning [this doctrine] from the Egyptians; for Okeanos is Osiris, and Tethys is Isis, since she nurses and nurtures all things.

Th 117

Thales as astronomer and author.

The discussion of the Pythian oracle centers on the question why wise sayings are no longer in meter but are given in plain prose. Comparable developments in philosophy and science are given to support the thesis that this should not be interpreted as a decline. Early philosophers such as Orpheus, Hesiod, Xenophanes and Empedocles had published their doctrines in the form of poetry. But although this practice was later abandoned, it does not affect the value of the philosophical content.

On the Oracles of the Pythia 18.402F–403A; 44.9–14

Nor did Aristarchus, Timocharis, Aristyllus, Hipparchus776 and their associates make astronomy less reputable by writing in prose, although Eudoxus777, [403A] Hesiod and Thales previously wrote in verse, if indeed Thales really composed the work Astronomy which is attributed to him.

Th 118778

Thales’ association with Egypt.

The Dinner of the Seven Sages779 takes place at a symposium held at the court of Periander, the tyrant of Corinth. Thales is present and his stay in Egypt is mentioned briefly.

Dinner of the Seven Sages 2.146D–E

And so we proceeded to walk, leaving the road and going through the fields at [146E] our leisure. Niloxenus of Naucratis was with the two of us, a capable man, who had associated with Solon and Thales and their group in Egypt.

Th 119

Thales and geometry, his association with Egypt and his wise sayings. Niloxenus, the emissary of Amasis, King of Egypt, says to Thales that Bias of Priene was not valued by the king only for his wisdom but also because, unlike the others, he did not refuse the friendship of kings.

Dinner of the Seven Sages 2.147A–B

... since in fact he [the king] admires you for other reasons, and in particular he was immensely delighted with your method of measuring the pyramid, because, without making any big effort or asking for any special equipment, you simply set your staff upright at the end of the pyramid’s shadow, and, since two triangles were formed by the contact of the sun’s rays, you showed that [the height of] the pyramid has the same ratio to [the length of] the staff as the one shadow has to the other. But, as I said, you have been slandered as being an enemy of kings, and some offensive statements [147B] of yours about despots were reported to him – for example, that when you were asked by Molpagoras of Ionia what was the most unexpected780 thing you had ever seen, you replied, ‘an aged tyrant’ (cf. Th 128; Th 237 [Diog. Laert. 1.36]; Th 564 [321e]). And again he was told that once at a drinking party when there was a discussion about animals, you said that the worst kind of wild animal is a tyrant, and the worst tame animal is a flatterer. Now even if kings claim that they are very different from tyrants, they do not take it kindly when they hear such words.”

“But,” said Thales, “that saying belongs to Pittacus, and he once said it as a joke about Myrsilus. But I myself would be amazed to see,” he continued, “not an aged tyrant but an aged ship’s pilot.”781

Sim. (measurement of the height of the pyramid) Th 107 (q.v.); (wise sayings) Th 89 (q.v.)

Th 120

Thales’ wise sayings.

Later comes the question as to what constitutes the fame or good fortune of a ruler.

Dinner of the Seven Sages 7.152A

Solon paused for a moment and then said, “In my view a king or a tyrant would gain the highest reputation if from a monarchy he were to establish a democracy for the citizens.” Bias spoke second, saying, “If he were the first to obey his country’s laws.” After him Thales declared that he thought a ruler’s happiness consists in reaching old age and dying a natural death (cf. Th 367).

Th 121

Thales’ wise sayings.

During the dinner a letter of Amasis to Bias is read out, which speaks of a contest of wisdom between Amasis and the King of Ethiopia. The Egyptian king had sent a question to the Ethiopian, whose answer did not satisfy Thales. He therefore gives his own answers:

Sim. (nature of god) Th 72 (q.v.); (wise sayings) Th 89 (q.v.)

Dinner of the Seven Sages 9.153C–D

What is oldest? “God,” said Thales; “for God is unbegotten” (cf. Th 90). What is biggest? “Place; for the cosmos contains within it everything else, but this [i.e., place] contains the cosmos“(cf. Th 351). What is most beautiful? “The cosmos; [153D] for everything that is orderly is a part of it.” What is wisest? “Time; for it has already discovered some things and it will discover the rest” (cf. Th 342).782 What is most widely shared? “Hope; for those who have nothing else have that” (cf. Th 371). What is most beneficial? “Virtue; for it makes everything else beneficial by putting it to a good use.” What is most harmful? “Vice; for it harms the greatest number of things by its presence” (Th 363). What is strongest? “Necessity; for it alone is invincible” (cf. Th 154; Th 341; Th 395). What is easiest? “What is natural; for people often discourage us from pursuing pleasures” (cf. in general the list in Th 237 [Diog. Laert. 1.34]; Th 564 [320]).

Th 122

Thales’ wise sayings.

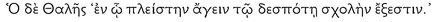

Dinner of the Seven Sages 11.154E [The best democracy.] After him Thales said that it is one that has citizens neither too rich nor too poor (cf. Th 366).

Th 123

Thales’ wise sayings.

Dinner of the Seven Sages 12.155D [The best household.] Thales said, [it is the one] “in which it is possible for the head of the household to have the most leisure” (cf. Th 370).

Th 124

Thales’ cosmology.

A discussion on vegetarianism. Cleodorus pleads for eating meat.

Dinner of the Seven Sages 15.158C

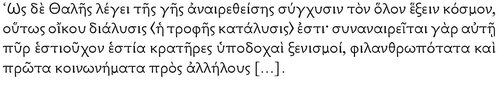

As Thales says, if the earth is destroyed it will be the ruin of the whole cosmos; in the same way [putting an end to nourishment] is the dissolution of the household. For when an end to put to it, that is the end of the hearth-fire, the hearth, wine-bowls, hospitality and entertainment – the most humane and basic acts of community among people.

Th 125

Thales’ wise sayings.

Later Gorgos, the brother of Periander, makes a contribution and informs them about his spectacular experiences. Periander says that he badly wants to speak about what they have just heard, but he is still hesitant:

Dinner of the Seven Sages 17.160E

“But I hesitate, since once I heard Thales say that we should say what is probable but be silent about what is impossible.” Then Bias interrupted and said, “But Thales also made this wise saying, that we should disbelieve our enemies even about the believable, and should believe our friends even about the unbelievable.”

Th 126

Thales’ Phoenician ancestry.

Later are related miraculous stories about the fondness of dolphins for humans, which must have tested the listeners’ credibility:

Dinner of the Seven Sages 21.163D

Following him [Pittacus] Anacharsis said that as Thales had done well to suppose that there is a soul in all the principal and most important parts of the cosmos, it is inappropriate to wonder whether the most excellent things are brought to pass by the judgment of God.

Th 127

Thales’ Phoenician ancestry.

On the Malice of Herodotus 15.857F; 14.10–12

Then again among the Seven Sages (whom he [Herodotus] calls “sophists”) he represents Thales as a Phoenician in origin (Th 12), of barbarian ancestry.

Th 128783

Thales’ wise sayings.

On the Sign of Socrates 6.578C–D

While Theocritus was saying this, Leontiades was leaving together with his friends and we entered and were greeting Simmias, who was seated on his couch, very gloomy and distressed, doubtless because his petition had failed. Looking at all of us, he said: “My God! [578D] What cruel and barbarous characters they have! Didn’t Thales of old give an excellent answer when his friends asked him, after he had returned from a long stay abroad, what was the strangest thing he had found out, and he said “an aged tyrant” (cf. Th 119, Th 564 [321e]). For even someone who has not suffered any personal harm is an enemy of lawless and unaccountable power on account of his disgust at the oppressive and harsh ways of such men.

Th 129784

Thales’ views on marriage and family.

Table Talk 3.6.3.654B–C

For what Zopyrus has just said has some sense, and I also see that the other time [that was suggested] has different difficulties and problems of timing. Therefore, the same way that Thales the Sage escaped when he was being bothered by his mother’s continual demands that he get married [654C], and misled her by saying to her at first, “It is not yet the right time, mother,” and later, “It is no longer the right time, mother” (cf. Th 237 [Diog. Laert. 1.26]; Th 564 [318]), so the best way for each man to deal with sex is to say, when he goes to bed, “It is not yet the right time,” and when he gets up, “It is no longer the right time.”

Th 130

Thales outsmarts a mule.

On the Cleverness of Animals 16.971A–C; 41.1–17

There are many examples of cunning, but I will pass over foxes and wolves and the tricks of cranes and [971B] jackdaws, for they are well known, and use as my witness Thales, the first of the Sages, who, they say, was admired not least for getting the better of a mule by a trick. One of the mules that carry salt accidentally slipped after entering a river and, since the salt dissolved, the animal was lighter when it got up. It recognized the cause of this and remembered it. And so, every time it crossed the river it deliberately ducked down and wet the bags, crouching down and leaning to each side in turn. When Thales heard of this, he told them to fill the bags with wool and sponges instead of salt, to load the mule and drive [971C] it. So when it played its usual trick and soaked its load with water, it understood that its cunning was unprofitable and from then on it was so attentive and cautious when it crossed the river that the moisture never touched its burden even by accident.785

Th 131786

Thales the Sage.

Originally there were five Sages, not seven, and this gave rise to an interpretation of the letter E, as the fifth letter.

The E at Delphi 3.385D–E; 3.24–27

For they say that those Sages whom some called sophists [385E] are five: Chilon, Thales, Solon, Bias, and Pittacus.

Decimus Iunius Iuvenalis (67–after 99/100 CE)

Th 132

Thales the Sage.

Satires 13.180–191

“Vengeance is a good that is sweeter than life itself! ”787

This is what the ignorant think, whose hearts

you see on fire for the slightest of reasons or for no reason at all.

However small the occasion, it is enough for their anger.788

But Chrysippus will not say the same, nor will the gentle

genius of Thales or the old man who lived near sweet Hymettus,

who would not have wished to give his accuser

any of the hemlock he accepted in his cruel bondage.

Wisdom, which makes us happy, gradually rids us of our very many vices

and all our errors,

first789 teaching us what is right790. For indeed

revenge is always the pleasure of a small, weak and trivial mind.

Sabinus (1st/2nd cent. CE)

Th 133

According to Galen, Sabinus writes that according to Thales man consists of water.

Galen, Commentary on Hippocrates’ On the Nature of Man 1.15.24.14–25.6 = Mewaldt CMG V 9.1.15.11–18, cf. Th 182

Agathemerus (1st/2nd cent. CE)791

Th 134

Thales and Anaximander.

Geography 1.1–2

Anaximander of Miletus792, the pupil of Thales, was the first who dared to draw the inhabited world on a tablet.

Pseudo-Plutarch (2nd cent. CE)793

Th 135

Eusebius cites (Pseudo-)Plutarch on the philosophers’ views about principles, stating that Thales was the first to hold water to be the principle of all things, for all things are from it and return to it.

Stromata: Strom. Fr. 179.1–40 Sandbach, cf. Th 260 (Eus. PE 1.7.16–8.3)

Pseudo-Hyginus (2nd cent. CE)

Th 136

Thales as astronomer.

On Astronomy 2.2.3

Very many people fall into error on the question why the Little Bear is called Phoenice, and why those who sail by it are said to sail more accurately and carefully, and why, if it is more reliable than the Great Bear, everyone does not sail by it. They do not seem to understand the background for the reason it is called Phoenice. For Thales, who researched these matters carefully and was the first to call it the Bear, was a Phoenician by descent, as Herodotus of Miletus says. Therefore all the inhabitants of the Peloponnese make use of the first Bear; the Phoenicians, however, [sail by] the one they learned about from the person who discovered it, and they are thought to sail more unerringly because they observe it more carefully, and truly they call it Phoenice from the race of its discoverer.

Th 137794

Thales the Sage; his wise sayings.

Fable 221795

The Seven Sages

Pittacus of Mitylene, Periander of Corinth, Thales of Miletus, Solon of Athens, Chilon of Lacedaimon, Cleobulus of Lindos, Bias of Priene. Their sayings are these:

“Measure is best,” says Cleobulus, the inhabitant of Lindos.

Periander of Ephyra, you teach that “All things must be planned carefully”.

“Recognize the right time,” says Pittacus, born of Mitylene.

“Most people are bad,” affirms that Bias of Priene.

And Milesian Thales warns of loss to him who pledges.

“Know thyself,” says Chilon, born at Lacedaimon.

Cepcropian Solon commands “Nothing in excess.”

Maximus of Tyre (2nd cent. CE)

Th 138

Water as the first principle.

Dissertations 26.2.f.1–h.2

And Homer, the leader of the group [of philosophers], is banned from philosophy from the time when sophisms from Thrace and Cilicia slipped into Greece, as well as Epicurus’s atom, Heraclitus’s fire, Thales’ water, Anaximenes’ breath, Empedocles’ strife, Diogenes’ jar, and the many camps of philosophers drawn up in formation against one another and [26.2g] shouting their war cries, everything full of words and whispering, of sophists battling sophists, but a frightening absence [26.2h] of results. And no one sees this famed thing, the good, on behalf of which the Greek world is at odds and divided into factions.

Th 139

Thales as astronomer.

Dissertations 29.7.i.1–11

The herd of humans, which grazes together most tamely, sociably and rationally, is in danger of dissolving and being torn asunder not only by banal desires or irrational appetites or pointless love, [29.7k] but by the most certain of all things, philosophy. This too creates many villages and myriads of lawgivers, but it tears asunder and scatters the herd and sends men in different directions, Pythagoras796 to music, Thales to astronomy, Heraclitus to solitude, Socrates to love, Carneades to ignorance, Diogenes [29.7.l] to labors, and Epicurus to pleasure.

Sextus Empiricus (2nd cent. CE)

Th 140

Water as the first principle; Thales and Anaximander.

Outlines of Pyrrhonism 3.30

Enough has now been said about the active [principle]. But we must also speak briefly of what are called the material principles. That these are inapprehensible is easy to conclude from the disagreement about them that has arisen among the dogmatists. For Pherecydes of Syros declared earth to be the principle of all things; Thales of Miletus, water; his pupil Anaximander, the unlimited; Anaximenes and Diogenes of Apollonia, air [ ...].

Th 141

Different views on the divisions of philosophy:

Thales as natural philosopher.

Against the Mathematicians 7.5

Thales, Anaximenes, Anaximander, Empedocles, Parmenides and Heraclitus conceived of only natural [philosophy]; everyone agrees on this without dispute as regards Thales, Anaximenes, and Anaximander, but there is no general agreement about Empedocles and Parmenides, or even Heraclitus.

Th 142

Thales as natural philosopher.

Against the Mathematicians 7.89

Such, then, was the position shared by these men [Metrodorus and others]; but the natural philosophers beginning with Thales appear to have been the first to initiate investigation into the criterion. For they condemned sensation as being untrustworthy in many cases and set up reason as the judge of the truth in things-that-are, and starting out from this they organized their views about principles, elements and other things, the apprehension of which results from the power of reason.

Th 143797

Water as the first principle; Thales and Anaximander.

Against the Mathematicians 9.359–360

For some have said that the elements of things-that-are are bodies, others that they are incorporeal. [9.360] Of those who have declared them to be bodies, Pherecydes of Syros said that the principle and element of all things is earth; Thales of Miletus, water; his pupil Anaximander, the unlimited; Anaximenes, Idaeus of Himera, Diogenes of Apollonia and Archelaus of Athens (Socrates’ teacher), [ ...].

Th 144798

Water as the first principle.

Against the Mathematicians 10.313

Hippasus, Anaximenes and Thales hold that all things have come to be from a single thing that is of a certain sort; of these Hippasus and according to some Heraclitus of Ephesus bequeathed the opinion that things are generated from fire, Anaximenes from air, Thales from water, and Xenophanes (according to some) from earth.

Irenaeus of Lyon (2nd cent. CE)

Th 145

Water as the first principle.

In his work directed against the Gnostics (preserved only in Latin translation) Irenaeus accuses the followers of Valentinus and others for their dependence on pagan philosophy.

Against the Heresies 2.14.2

And not only are they convicted of putting forward as their own views that have been proposed by comic poets, but they also amass the sayings of all who do not know God and who are called philosophers, and as if they are stitching together a patchwork quilt out of a lot of poor rags, by means of their refined eloquence they have made for themselves an artificial surface. They introduce a doctrine that is indeed new, because it has now been presented with a new art, but it is in fact old and useless since the same old doctrines have been sewn up out of old dogmas that reek of ignorance and blasphemy. Thales of Miletus said that the origin and beginning of all things is water; but saying that it is water is the same as saying that it is the Depth. Also Homer the poet dogmatized that Okeanos is the origin of the gods and Tethys their mother, which these people [the Valentinians] take over as the Depth and Silence. Anaximander introduced as the beginning of all things that which is immense, having in itself seminally the origin of all things; he declares that immense799 worlds arise from it. This too they have transformed into their Depth and their Ages.

Pseudo-Plutarch (ca. first half of the 2nd cent. CE?)

Th 146

Thales’ identification of principle with element.

In this passage, which shows Aristotelian influence,800 Thales stands for monists who admit only one material principle.

Placita Philosophorum 1.2.875C4–D7