Goal: Train wisely and develop strategies to finish the longest race of your dreams

Around 4:35 a.m. on June 26, 2016, I ran through a neighborhood in Auburn, California, on the way to a high school track that hosts the finish line of the Western States 100-Mile Endurance Run.

My headlamp illuminated bundled-up spectators cheering at the side of the road. A surge of emotion tightened my throat and made tears spring up in my eyes. The tears felt good, relieving the itchy redness caused by running through dust all day.

Breathing deeply, pumping filthy arms covered with dried sweat and dirt, I willed myself to maintain a jog in spite of bone-deep fatigue that pleaded with me to stop and walk.

I silently repeated the mantras that had entered my head out of nowhere, some 20 miles earlier, whose catchy rhymes, in rhythm with footsteps, reinforced my resolve to run and not give up: Get it done, I can run. Suck it up, Buttercup. (Buttercup? I don’t know where that self-inflicted nickname came from but, in the moment, it worked, chiding me not to be a delicate flower.) With only a mile left to go, new energy flickered and flowed through my legs, like a dead car battery getting a jumpstart.

It took over twenty-three-and-a-half hours to reach this point, since starting the race at 5 a.m. the prior day, 99 miles back in the ski resort of Squaw Valley. But really, it took most of my adulthood to get here. I was on the verge of fulfilling an ultimate trail-running dream—finishing the most historic and prestigious 100-mile race in the country, under a goal time of 24 hours—because of all I had learned from two decades of consistent running.

My running career flashed through my mind, starting with that first marathon in 1995. All those training runs. All those practice ultras. Some disappointing races. Some injuries and comebacks. Three prior 100-mile finishes. Four years of qualifying to enter the Western States Endurance Run lottery, and finally getting picked for a spot. Six months of deliberate, concentrated training following the New Year. Countless hours studying the course. Long drives to practice on the course. Long drives with the car heater turned on full blast, to adapt to the furnacelike heat we faced in the forested canyons of the Western States 100.

It took all that and more to approach the finish. Was it worth it? I would find out in a matter of minutes.

Running calmly by my side, my friend and pacer, Clare Abram, said, “Almost there—you’re doing great.” At last, it was true: We really were almost there.

Suddenly I heard, “Mom!”

My fifteen-year-old son, Kyle, dressed in an oversized hoodie and long basketball shorts, waved his arms and jumped up and down near the entrance to the track. He ran toward us and joined my side, the untied laces on his skateboard shoes flapping haphazardly.

We entered the track, where floodlights showed bleachers filled with onlookers cheering as if it were the Olympics. The finish line stood 300 meters away—we just had to make it around this lap. Suddenly I heard again, “Mom!”

My eighteen-year-old daughter, Colly, was kneeling down in skinny jeans near the track’s edge, filming us on her phone, which she quickly pocketed. Then she, too, started running next to me, her long blond hair flowing.

“C’mon kids—let’s do it!” I shouted, picking up my pace to what felt like a sprint while my two teens kept up, one on each side.

The announcer—the familiar voice of a friend, Tropical John Medinger—said my name over the loudspeaker. Numerous faces I recognized lined the edge of the track, mirroring the big smile I felt on my face. I heard my name shouted from the bleachers and looked up in surprise to spot my first coach, Alphonzo Jackson, fists in the air, standing up and cheering. I glimpsed the profiles of my son and daughter, expressing the joy they showed as little kids running around a playground.

Then, as I burst over the finish line and heard exclamations of congratulations, I saw the clock: 23:44:45. Numbers that represented a dream come true. Was it worth it? Hell, yeah!

How to Adapt Your Trail Training for Ultra Distances

I share this story not only to describe what it can feel like to finish a 100-mile race, but also to illustrate all the preparation that’s necessary and worthwhile.

Becoming an ultrarunner is an evolutionary process, and ultramarathon preparation builds on a foundation of consistent shorter-distance trail running. You have to put in the time and the work; shortcuts lead to DNFs and injuries.

If you skipped earlier chapters and started reading at this point because you want to jump into ultrarunning, then please stop and go back. Review and practice the advice from each preceding chapter. The training principles and skills covered earlier are essential for ultrarunning.

To recap, those main training principles are:

● Aim for consistency by developing a weekly routine that revolves around three high-quality hard workouts that stress your body for enhanced cardiovascular fitness, strength, and endurance: a midweek speed workout, a longer midweek hill workout (ideally, on a trail to practice trail-specific challenges), and a long trail run (Chapters 3, 4, and 10). Supplement running with a modest but essential amount of conditioning (Chapter 5) throughout the week. Fill the days between hard runs with easy runs and rest, allowing your body to adapt to the stress of the challenging workouts.

● Use a four-step process to train for trail races: build your base (Chapters 3 to 5); enhance your fitness and increase your volume (Chapter 10); prepare specifically for the conditions of your race (Chapter 10); taper and plan race-day execution (Chapter 11).

● To be a successful trail runner, especially at ultra distances, takes a certain mindset (Chapters 1 and 12), appropriate gear (Chapter 2), trail-specific running techniques (Chapter 4), proper hydration and nutrition (Chapter 7), safety and survival skills (Chapter 6), and an understanding of how to prevent and troubleshoot common trail-running problems (Chapter 8).

Training for an ultramarathon follows the same principles as training for shorter trail races, and relies on the same trail-specific techniques, with a few key modifications.

The most important ultra-specific training modifications involve:

● More time on your feet: Increase the duration of your long training runs and the overall volume of your training week.

● More training of your gut: Practice and adapt to refueling and hydration during day-long runs.

● More mental toughness: Develop psychological strategies to persevere while experiencing fatigue and discomfort.

We’ll cover each of these three aspects for ultra-distance training below. Keep in mind that these modifications matter most when you aim to graduate to the 50-mile distance and beyond.

As mentioned earlier, training for a 50K is not significantly different than training for a trail marathon. In a 50K, you can get by with refueling and hydrating much as you would during a trail marathon or during a long training run. Also similar to a trail marathon, as covered in Chapter 10, you should aim to work up to a peak long run for 50K training that takes at least 75 percent of the time you estimate it will take you to finish the 50K. If you anticipate a 50K will take 6.5 to 7 hours, for example, then you should be able to confidently complete a long training run that lasts at least 5 to 5:15 hours, which at a 12-minute/mile average pace is 25 to 26 miles. Hence, running a trail marathon four to five weeks before a goal 50K serves as an excellent peak long training run for a 50K.

When you add 19 miles to a 50K for your first 50-miler, however, then you have to modify your training to prepare for steady running and hiking for the better part of a day. (A fast 50-mile time is 7.5 hours or less—a 9-minute/mile average pace or faster—but average first-time 50-milers should expect to take at least 10 to 12 hours to finish.)

The most obvious—but not the only—way to prepare for 50 miles and longer is to lengthen the long run.

LENGTHEN YOUR LONG RUNS AND ADD TIME ON YOUR FEET

Lynne Hewett, one of my tent mates during the 2012 170-mile Grand to Grand Ultra stage race, doesn’t run much more than an average runner who trains for a marathon, yet she successfully completes grueling ultramarathons. Her secret? She is an emergency room nurse, on her feet all day while working extra-long shifts. Due to the circumstances of her career, her body has adapted to constant locomotion, often in a state of fatigue, making her well suited for ultrarunning.

Many of us work sedentary jobs during the day, however, so we have to hack our schedules to spend more time on our feet.

Continue to follow the guidelines outlined in the section, “Enhance Your Fitness and Increase Your Volume” in Chapter 10, plus follow these tips to gradually increase the duration of your long runs and your overall weekly volume.

● Build your long training run to the marathon point, then go slightly longer. For 50-mile to 100-mile training, plan a few key long runs during your peak training that stretch from 26 to 31 miles to the mid- or high 30s. If you have a goal of a 50-mile or longer race four to six months away, then plan your season to include one or more trail marathons and trail 50Ks as supported long runs (aka C-level races, as discussed in Chapter 9). For 100-mile race training, schedule a 50-mile or 100K race two to three months earlier as a stepping stone to that big goal, giving yourself adequate time to recover from the 50-miler or 100K, and resume peak training before starting to taper for the 100-mile race.

● Alternate extra-long training runs most weekends with a back-to-back training run every three to four weeks. A back-to-back deliberately violates the guideline of alternating easy/hard days. But by following a long run with another substantial trail run the next day, you adapt your legs to running and hiking while fatigued. I recommend splitting back-to-backs unevenly, so the first day is slightly longer than the next day’s follow-up run (for example, a 25-mile or approximately 5-hour run on Saturday, and an 18-mile or approximately 3.5-hour run on Sunday). Pace the second day’s run very easily and downshift to hiking frequently, to keep your heart rate and breathing low enough to maintain a conversation. Beware, however, that this “easy” pace will feel hard because you’re fatigued from the prior day’s long run—and that’s the point! The second day of a back-to-back helps you prepare for ultramarathons by experiencing steady forward motion on fatigued legs, while also cultivating patience and practicing other mental strategies covered later in this chapter.

● Once a week, on a hard day (for example, when you have a speed workout in the morning), run and hike at a very easy pace late in the day for sixty to ninety minutes. This “two-a-day” serves a similar purpose, but on a smaller scale, as the back-to-back described above. Additionally, if you habitually run in the morning, then a two-a-day forces you to experience running on fatigued legs at a completely different time of day. To prepare for an ultramarathon that’s 50 to 100 miles long, and could take anywhere from 10 to 30-plus hours, it’s important to practice running on fatigued legs at different times of the day.

● Walk and stay active as much as possible throughout the day. Review the tips in the section “Real-Life Ways to Find More Time to Run” in Chapter 3. The more you can fit walking and additional easy-pace running into your everyday life, the better for ultra training.

● Plan an easier week every three to four weeks. Follow the advice from the section “What Should My Total Weekly Mileage Be?” in Chapter 10 to give yourself more recovery time to adapt to high-volume training. Cut back your weekly volume by roughly 25 percent. For example, if you build up to 60 to 65 miles each week, two to three weeks in a row, then take a week where you run “only” 45 miles. Do this by converting an easy day to a complete rest day, and by shortening your long run. Look ahead on your calendar, and if you know you have a week during which it will be difficult to train at high volume due to work or family commitments, then deliberately plan for that to be a “cutback week,” and work your high-volume weeks around it.

TRAIN YOUR GUT TO HANDLE REFUELING AND HYDRATION PAST THE 50K

When I was pregnant with my first child, I felt overwhelmed by the amount of contradictory and highly detailed advice available to new parents. Similarly, new ultrarunners often feel overwhelmed and confused by all they hear regarding what, when, and how to eat and drink during an ultramarathon.

The best parenting advice I ever heard also is the best advice for refueling and hydrating during an ultra: “Do what works.” Set aside rigid notions of what you should or should not consume, and instead eat or drink whatever feels best in your digestive tract, and works best to sustain your energy for forward movement.

To figure out “what works” takes practice and experimentation. Start by carefully reviewing the guidelines for nutrition and hydration in Chapter 7, as well as Chapter 8’s sections on diarrhea and upset stomach. Consider the amount of calories you are likely to burn, the amount of hydration and electrolytes you are likely to need (affected by the climate), and the distance and pace that you plan to run.

If, for example, you plan to race an ultra competitively at a high effort level that keeps your heart rate and breathing high enough to make it difficult to talk in full sentences, then you may be best off consuming primarily quick-burning, easily digestible carbohydrates (gels and sports drinks). This strategy enabled Magdalena Boulet to win her 100-mile debut, the 2015 Western States Endurance Run, consuming only GU Roctane drink, and defying the prevailing wisdom that you should eat “real food” during an ultra. It’s also a strategy I successfully used in the 2016 Lake Sonoma 50-mile race, consuming only gels and one 160-calorie Honey Stinger Waffle, along with sports drink and soda.

If, however, you are like most ultrarunners and plan to run 50 to 100 miles at a sustainable conversational pace, then you likely will benefit from a variety of fuel sources, especially as you stretch past lunchtime and begin to crave “real food.” Salty and sweet snacks that mix some protein and fat along with complex carbohydrates are excellent choices for ultrarunners. Trail mix, half a peanut-butter-and-jelly sandwich, or turkey and avocado rolled up in a wholewheat tortilla are some of my personal favorites for day-long training runs, or for 100K and 100-mile ultras.

Some ultrarunners, such as Scott Jurek, thrive on healthy vegan fare during an ultra. Others thrive on junk food; Clare Gallagher won her 100-mile debut, the 2016 Leadville 100, fueled by cake frosting and candy. Do what works.

You don’t have to wait for a weekend long run to experiment with refueling and hydrating. Alter your training schedule during the week for some postprandial runs to give yourself additional opportunities to practice running while digesting food. Have a light lunch or small dinner with the types of food you might eat at an aid station (for example, a quesadilla, noodle soup, or PB&J), then start your run. Or, for a mid-morning or mid-afternoon run, try a snack such as an energy bar before you hit the trail.

Then, on your weekend long training runs, take solid-food options to try in addition to simple-sugar fuel. Start your long run mid-morning and run through the mid-afternoon; that way, you can practice eating the equivalent of lunch during your run. As you experiment with these types of food in your gut during a run, you’ll discover what gives you gas or an upset stomach, and what feels good and easy to digest.

Below is a sample peak-training week that incorporates the two ultra-specific training modifications covered above: more time on your feet, and more training of your gut.

A Sample 70-Mile Peak Week for Ultra Training

For most nonelite ultrarunners, a training week with approximately 70 miles (roughly 13 hours) of running and hiking serves as a smart target for peak-training volume to prepare for an ultramarathon of 50 miles or longer. Ideally, this high volume is achieved for two to three consecutive weeks before beginning a three-week taper before the goal ultra.

You can complete a 50-mile or longer ultra on lower-volume training, however. It’s just not ideal. With a minimal amount of training, you could find yourself in “survival mode” during your ultra—but, with mental tenacity and smart problem-solving strategies, you can survive to make it to the finish.

I support the guidelines developed by ultrarunning coach Jason Koop for the minimum amount of training time required to be successful at a 50K to 100-mile race; however, I wouldn’t recommend these minimal levels, unless your circumstances (for example, work demands) or your desire to cross-train heavily (for example, you’re a triathlete) prevent you from devoting more hours to running and hiking. You should view Koop’s guidelines as the floor, not an optimal target, to finish ultra distances:1

● For a 50K to 50-mile race: a minimum of at least six hours per week for three weeks

● For a 100K to 100-mile race: a minimum of nine hours per week for six weeks

Over the years, through research and anecdotal evidence, I’ve found that hitting a peak of approximately 70 miles per week during the month prior to an ultra is a “sweet spot” for most aspiring ultrarunners training for a 50-mile ultra or longer. At an average pace of approximately 11 minutes/mile, the total time for 70 miles equals close to thirteen hours. (Many run faster than 11 minutes/mile on road, but miles running and hiking on trail are substantially slower, so an 11-minute/mile pace is a reasonable average for mid-pack runners.)

One example of what a 70-mile week might look like follows below. Remember the caveat to “Beware of others’ training plans,” and keep in mind this is only one example of a high-volume training week incorporating the training principles discussed. Individuals should modify weekly training based on their unique fitness levels, goals, and life circumstances.

Also note that during peak training, your body probably will feel extra stiff and fatigued. It’s important, therefore, to start each run with the dynamic stretching routine outlined in Chapter 5, to gradually warm up and preserve a good range of motion, which in turn helps prevent injury.

MONDAY

● Easy-pace recovery run on trail. Time: 1 hour; 5 to 6 miles

● Upper-body conditioning (core and arms), plus foam rolling and PT exercises concentrating on foot/ankle care; 25 minutes

TUESDAY

● Morning tempo-pace run: Run easily to warm up for 20 minutes; do a set of 6 x 30-second strides with 30-second recovery; run easily another 4 minutes. Accelerate to “comfortably hard” tempo pace (8 to 8.5 on a scale of 1 to 10 perceived effort) for 30 minutes. Run easily to cool down another 15 minutes. Time: 1:15; 7 to 9 miles

● After-dinner easy run/hike: First, eat a light meal to practice adapting to trail running after eating; also, prepare to practice nighttime running with a headlamp after sunset. Start with brisk hiking to warm up gradually and practice power hiking. Enjoy an easy-pace nighttime run for about an hour or slightly longer. Time: 1 hour to 1:15; 5 to 8 miles

WEDNESDAY

● Easy midday run: First, consume a solid-food snack that you might eat during an ultra; run during lunchtime or afternoon to practice running in the heat while digesting. Keep the pace easy and relaxed. Time: 1 hour; 5 to 6 miles

● Conditioning with emphasis on core, balance, and PT to address weak areas; 25 minutes

THURSDAY

● Medium-length hilly trail run: Choose a trail route of approximately 12 to 13 miles, with a variety of hills. Run/hike the uphills with focus and effort; run the downhills steadily and practice good form. (If a hilly route is not available, find a hill or stairs near the end and do a set of repeats.) Time: 2:15 to 2:30; 12 to 13 miles

FRIDAY

● Rest and sleep in as long as possible.

● Active recovery: Take a short walk followed by stretching or gentle yoga, or swim for a half hour or less at an easy effort level.

SATURDAY

● Long trail run: Trail marathon treated as a C-level race or equivalent. Choose a route that mimics your goal race as much as possible, in terms of elevation profile and terrain. Aim for a relaxed, steady pace. Time: 5 to 5:30; 26 to 27 miles

SUNDAY

● Short recovery run after lunch: First, eat a light meal or snack of the type of food you might eat at an aid station. Choose a gentle, runnable route and run at an easy pace; adapt to digestion and daytime heat while running. Time: 1 hour; 5 to 6 miles

TOTAL WEEKLY TIME AND MILEAGE:

12.5 to 13.5 hours (not including conditioning), 65 to 75 miles

An alternative to the training week above could feature a back-to-back long run on the weekend, with the two days’ runs totaling approximately 40 miles. The week’s remaining miles (approximately 30) would be spread throughout the weekdays.

Consistently training and building up to a weekly volume of approximately 70 miles will not guarantee you’ll finish an ultra, however. The third and perhaps most important ultra-specific training aspect involves your mind.

It’s (Almost) All in Your Head

Dean Karnazes, bestselling author of Ultramarathon Man, noted this about the Western States Endurance Run: “There’s a famous saying that you run the first 50 miles with your legs, and the next 50 miles with your mind.”2

As mentioned in Chapter 12, ultrarunning takes “mental toughness.” What does it mean to be “mentally tough” or to run an ultra “with your mind”? It means using certain psychological coping skills and behaviors to increase your tolerance for the physical challenges and discomforts of ultrarunning.3

Inevitably, during an ultra, you’ll experience low points sparked by physical factors such as muscle fatigue, joint pain, low energy, dehydration, digestion problems, or blisters. Your psychological response largely determines whether you will keep going in the face of adversity. Will you become grumpy, feel sorry for yourself, and focus on how much this sucks? If so, a normal response will be to stop to make those feelings go away.

Alternatively, if you cultivate the habit of deliberately responding more positively to adversity, then you are more likely to keep going, and whatever is causing you discomfort is more likely to improve. Examples of positive responses involve problem-solving (“What can I do to make this feel better?”), acceptance (“I know this is part of the nature of endurance sports and what I signed up for.”), gratitude (“I’m lucky I have the good health to experience this and glad I can view this scenery.”), and humor (“I’m getting my money’s worth by going so slowly.”).

Above all, finishing an ultramarathon requires desire and determination. Before I attempted my first 100-mile race, my friend Jennifer O’Connor—a 100-mile veteran—told me, “You have to really, really want to finish. Otherwise, there will be every rational reason in the world to quit, and you will give in and quit.” She’s right.

One common logic trap that leads to a DNF (“did not finish”) goes like this: You are midway through an ultra-distance route, and you are tired and uncomfortable. The run stopped being fun several miles ago. You think to yourself, “I’m satisfied with what I’ve accomplished so far, and I’m glad I got to experience this event, but I will feel so much better if I call it a day now. It’s just not my day; I’ll save myself to run well at another race.” Suddenly, dropping out seems like a win-win situation that makes all the sense in the world.

After you quit and the relief of resting wears off, however, you’re almost guaranteed to experience regret. Eventually it’ll sink in that you failed the main test of the ultramarathon—the one that’s the essence of ultrarunning—which is persevering through fatigue and discomfort. Running an ultramarathon is supposed to be difficult and tiring at times. Pushing through those tough times ultimately is what makes the experience so rewarding.

Part of your ultra-distance training, therefore, should include mental training to recognize and deal with those moments when your mind argues with you to quit. Practice the following strategies during all your training runs so they come naturally to you on race day.

MANTRAS AND OTHER MENTAL STRATEGIES

At some point during a long training run or race, your mind may buzz with negativity. You’ll ruminate on things that went wrong in the earlier miles, or anxiously worry about the miles to come. You may even mentally compose a short story to use on your social media platforms that justifies all your excuses for dropping out or finishing far off your goal.

It’s important to catch yourself in that negative frame of mind, and refocus on running the best you can under the circumstances, or else you’ll continue on a downward spiral that will doom your performance. An easy and effective way to quiet the negative buzz in your head, and improve your running, is to repeat a mantra in rhythm with your stride.

A mantra can be any catchy phrase that makes you feel better and self-coaches you to improve your forward motion. One of my favorites to repeat in the early miles of a race, for example, is “relax, no stress.” In my head, I say each syllable (“re-lax, no-stress”) as my foot hits the ground, which helps me run well and avoid starting the race with a too-fast pace. Other mantras I recommend include, “so far, so good” and “be smart, be strong.”

Chances are a mantra will pop into your head that fits the circumstances. On day 3 of the 2016 Grand Circle Trailfest in southern Utah, for example, my legs ached from the cumulative fatigue of the first two days’ races, and I felt anxiety about the competition. So many worried thoughts swirled through my head that I couldn’t focus on the primary task of running well. Then, the mantra “find a flow, let it go” came to me, and instantly helped. I let go of worrying about the competitors and focused on “flowing” or running as well as possible, which ultimately helped me nab the third-place podium spot.

Here are some other mental tricks to help you endure through ultradistance training and races:

● Break it down: “Take it aid station to aid station” is a tried-and-true nugget of advice among ultrarunners. It means to break the Herculean task of an ultra into achievable segments. When you are midway through an ultra and struggling, don’t focus on all of the miles remaining; focus instead on getting to the next aid station, period. If even getting to the aid station feels too daunting, then focus on getting to the next course-marking ribbon. On a larger scale, plan to break your race into chunks and mentally “hit the reset button”—that is, try to feel fresh and positive—at the start of each new phase.

● Bring it on: Instead of fearing or dreading a tough segment of an ultra—such as a hard climb to a summit, or a technically tricky stretch of singletrack—fortify your resolve with a “bring it on!” toughness and enthusiasm. Embrace the challenge and congratulate yourself on attempting it. Have faith that you are tougher and can endure more than you think. I developed this habit during the Grand to Grand Ultra multiday race. Anytime I faced an extraordinarily difficult stretch—such as climbing up a vermillion cliff, or bushwhacking through prickly, dense vegetation—I forced myself to say out loud, “Yahoo! I’m earning my ultra credentials today. Bring it on!” This habit pushed away that self-doubt and self-pity that threatened my ability to persevere.

● Accept the suck: “The suck” during an ultra-distance trail run might involve slipping in mud, suffering in cold rain, going off course, cramping from an extra-high effort level, or throwing up what you just ate. At those moments, resolve not to complain and not to feel sorry for yourself. Instead, accept the mishaps and discomforts as part of the ultrarunning process, and view them as signs you’re digging deep and pushing your limits. Tell yourself, “I know it’s temporary, and I can handle it!” Focus on what you are doing well, what doesn’t hurt, and what you can do to improve the situation.

● Fake it ‘til you make it: Even when—or, especially when—you feel horrible during an ultra, pretend that you feel fine and strong. Smile and behave toward others as if you are doing great. Most of the time, this behavior genuinely makes you feel and run better. When I enter an aid station feeling worn out, and a volunteer asks how I’m feeling, I say something absurdly false, such as, “Fresh as a daisy!” This silly, upbeat response—along with the positive reaction from the people around me—always cheers me up.

● Promise to treat yourself to something: If you are not feeling intrinsically motivated during a long run, then develop an extrinsic motivator—a reward to claim if and only if you finish. This could be an extra day off, an hour-long massage, or a whole pizza, whatever “carrot” keeps you going. During 100-mile races, my friend Rachel Bell Kelley puts her favorite cookies (ginger snaps) in drop bags that are waiting for her at checkpoints in the later miles of the race. She craves these cookies and treats herself to them only at Mile 70 and later in an ultra.

● Don’t be a whiner; avoid them: Negativity is contagious. If you’re running near people who are complaining, then get away from them before they bring you down. Ultrarunner and race director John Trent learned this lesson at the 2001 Western States Endurance Run. Running with his good friend Scott Mills, they found themselves stuck behind an unrelenting complainer. “Everything out of this man’s mouth was how badly he was feeling, how the day was going to heck in a handbasket, how the aid stations were crap, and how he hated running,” John told me. “After about two miles of this nonsense, Scott tapped me and said, ‘Follow me.’ We managed to run around the guy and get ahead. Then Scott said something I’ve never forgotten: ‘You train too hard and too long to have a negative personality ruin your race like that. Avoid all negative personalities in any important race you run. If you don’t, their negativity becomes your negativity.’”

KNOW WHEN TO TOUGH IT OUT AND WHEN TO QUIT

An ultrarunner should commit not to quit. But when is it OK—even smart—to quit? The answer can be a tough judgment call.

Some say DNF (Did Not Finish) should also mean Did Nothing Fatal. In other words, you should quit only when it’s a true medical emergency.

Joe Grant of Gold Hill, Colorado, was a top runner in the grueling 2016 Hardrock 100, but midway through the race, he whacked his forehead while passing through a stone tunnel. He tried to continue, but recognized the symptoms of a concussion and wisely realized that running another 50 miles over high-altitude mountain passes would be neurologically dangerous. His Hardrock DNF certainly qualifies as necessary. Other examples include breaking a bone, urinating blood due to kidney malfunction, or becoming clinically hypothermic, heat-exhausted, or hyponatremic.

With other physical problems, however, it’s less clear whether to quit or risk continued running. A painful rolled ankle, for example, can feel OK after a mile or more, especially if it’s wrapped for support. Episodes of nausea or diarrhea, which lead to calorie depletion or dehydration, can clear up in the second half of an ultra.

To help determine whether you should quit, ask yourself the following questions. “Yes” means you should drop. If the answer is “maybe,” then factor in how important the race is to you to finish and how risky it would be to continue.

● Are you risking life or limb, or might you need hospitalization (for example, from renal failure or severe altitude sickness) if you continue?

● Is the problem significantly affecting your ability to bear weight on a foot and run symmetrically (are you limping?), and does it worsen when you continue?

● Have you been unable to digest any calories or fluids for several hours due to upset stomach, and do you still face four or more hours until the finish line?

● Are you in the midst of a less-important B- or C-level race, or on a long training run, leading up to your goal A race, and experiencing problems that likely will lead to injury?

Remember, feeling tired, bored, or generally uncomfortable is not a good reason to quit. Pushing through fatigue, boredom, and discomfort is essential for successful ultramarathoning.

Nighttime Running and the Sleep Monsters

If you decide to train for the quintessential ultrarunning goal of 100 miles, then get ready for an all-nighter like no other!

Running in the dark is not as hard as it may sound, but it tends to be significantly slower because poor visibility and fatigue affect pace. Gear-wise, you’ll need two main things:

1. A good headlamp, flashlight, or combo of the two. Review Chapter 2’s section on lighting for predawn or nighttime running, and obtain a powerful and comfortable light source.

2. Extra clothing layers for warmth due to the slow pace and nighttime chill.

Sleepiness, not darkness, is the main challenge that all-night running presents. From midnight through sunrise, you may battle the so-called “sleep monsters” of fatigue mixed with mild hallucinations. Having a pacer (another runner who accompanies you) to talk to can greatly help you through these dark, drowsy hours, as you fight the desire to take a nap trailside (which can be dangerous if you’re solo and in cold weather).

Most ultrarunners strategically use caffeine from energy gels and drinks during an all-night run. To get a greater caffeine boost during these sleepy hours, wean yourself off coffee and other caffeine sources in the weeks preceding an all-night ultra, and avoid caffeine during the first half of your ultra. Then, as nighttime sets in, start drinking caffeinated cola and consuming caf-feinated energy gels to keep you awake until sunrise.

Sometimes, it can feel virtually impossible to avoid a nap, as I discovered during my first twenty-four-hour race in 2015, which took place on a 1-mile loop course. The monotony of the loops lulled me into a state of sleep-running, and only willpower and the glow of sunrise on the horizon kept me from curling up in a parked car to nap. Chocolate-covered espresso beans helped, too!

My friend Yitka Winn, an experienced ultrarunner who’s completed several 100-mile adventures through the night, shared the following advice if you’re trying to decide whether to nap mid-run:

“Sleepiness has a lot in common with an intense craving for, say, a bowl of ice cream,” she says, explaining that you have three options: one, satisfy the craving immediately; two, deny yourself and distract your mind by thinking of something else; three, torture yourself by obsessively thinking about how good that ice cream or nap would be while still denying yourself it.

“When it comes to intense sleep cravings, option one may be your best bet if it’s the middle of the night and neither sunrise nor the finish line are imminent. Set an alarm on your phone or watch and take a power nap—ideally at an aid station, or by the side of the trail with your pacer watching over you—wearing all your warm layers. Option two may be the best option, if you can pull it off. Talk, sing, do math in your head, splash cold water on your face; do anything you can to get your mind off ‘All I want to do is sleep.’ But, avoid option three at all costs, which will do nothing but make you miserable!”

Get Ready for Race Day: Drop Bags and Crews and Pacers, Oh My!

The date of your ultramarathon is only a couple of months away. Carefully review the advice in Chapter 10, to make sure you are preparing specifically for the conditions of your ultra, and also Chapter 11, to plan your tapering and race-day execution. Those guidelines and tips apply to trail races of any distance.

Additionally, if you are training for a 50-mile or longer ultra, you should plan whether to use a pacer (if pacers are allowed), a crew, drop bags, or some combination of all three (refer to Chapter 12 for an introduction to pacing, crewing, and drop bags).

Remember the KISS principle: “Keep It Simple, Stupid.” Many runners unnecessarily complicate their race-day plan with too much gear shoved into unnecessary drop bags, too many crew members, and unreliable pacers. Most ultras can be run solo with the assistance of aid stations and, for longer ultras, one or two drop bags. But if you feel you would benefit from the camaraderie of a crew at aid stations, and the safety and encouragement of a pacer during the later miles, then plan accordingly.

Follow these guidelines to assemble a small but effective team and a just-right amount of extra stuff:

● Use drop bags only if you need something that the aid station cannot provide and that you cannot comfortably carry in your hydration pack, such as a headlamp, extra layers of clothing, and special snacks or drink mixes. Finding and accessing your drop bag at an aid station can add several minutes to your race time, so if you are running competitively, forgo a drop bag unless it’s essential.

● For essential items you don’t want to carry the whole time (like a bulky headlamp), use a drop bag rather than your crew to make sure you’ll get it. Drop bags are virtually guaranteed to be at a checkpoint waiting for you, but the same cannot be said of crew members, who can be lost or late.

● Choose crew members carefully, and limit the number to two or three. The ideal crew member takes the job seriously, is completely focused on the runner’s needs, and doesn’t mind driving long distances and waiting many hours. Ideally, crew members are ultrarunners who understand the needs and moodiness of a runner mid-ultra. Beware of asking a spouse or other loved ones to be crew, as their concerned looks or complaints about waiting around for you can ruin a positive mood, or even spark you to drop out.

● Appoint a crew chief who’s in charge of race-day logistics, and have him or her assign very specific tasks to others. Tasks might include refilling water bottles; applying sunscreen on the runner; removing trash from runner’s hydration pack; replenishing runner’s stock of gels and other calories; taking photos.

● Provide your crew with detailed printouts of maps, checklists, and expected arrival times to aid stations. Printouts are important because in the backcountry, cell phones often don’t have coverage. Hold a pre race meeting to go over these instructions and the race-day timeline. Try to do it about a week before race day so you have time to adjust your plan, if necessary. Touch base with your crew members again on the night before the race to confirm they’re ready, and to handle any last-minute changes that could be caused by a surprising weather forecast or a course reroute.

● Choose a pacer carefully, separate from your dedicated crew member(s). A pacer’s primary task should be to meet the runner at a designated spot, with plenty of time to spare, ready to run and encourage the runner. A pacer should be entirely reliable and self-sufficient so the runner doesn’t have to worry about whether the pacer has adequate food, drink, or gear. Choose someone you’re confident will run at your pace and boost your spirits. Also, make sure the pacer is familiar with the course route, to help you avoid going off course, and that the pacer knows the distances between aid stations.

● Make sure crew members and pacers know and follow the event’s rules, so that you don’t get disqualified. Examples of rule violations include the pacer carrying the runner’s gear (known as “muling”), or the crew meeting the runner outside of designated aid station areas.

● Never forget that you, the runner, retain responsibility for taking care of yourself. If you enter an aid station and don’t see your crew or pacer waiting as expected, then focus on getting what you need, being self-reliant, and continuing with your race; don’t let their absence frustrate you and sabotage your performance.

● Always remember to thank your crew members and pacer, reimburse their expenses if possible, and plan to take them to dinner or throw a celebration party afterward.

How to Make a Pace Band

When you face an ultra race on an unfamiliar course, it’s useful to have a handy reminder of the event’s aid station locations and a guesstimate of how long it will take to reach them—especially if you have a crew or pacer meeting you at any of those checkpoints.

I recommend making a homemade pace band, which is a laminated bracelet that lists the aid stations’ mileage and your “fast pace” and “slow pace” estimates of getting to them. That way, when you reach an aid station, you are reminded of how far to go until the next one, and you have a sense of whether you’re running near the fast or slow end of your anticipated pace range.

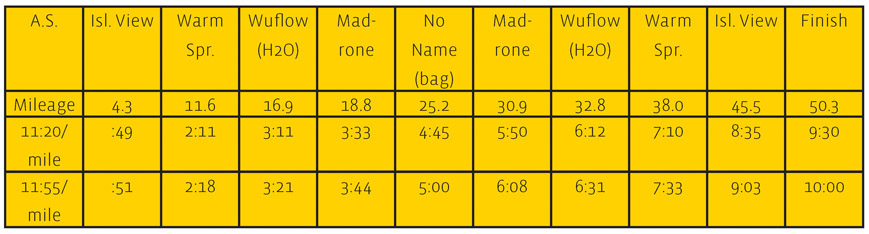

Here’s how to do it: Let’s use the Lake Sonoma 50-mile ultra as an example.

First, use the “Table” function in Microsoft Word to create a table with four rows. Count the number of aid stations at the ultra; use that number, plus one, for the number of columns. Label the top two rows in the first column, “AS” and “mileage”; then, along the top row, list the aid station names. In the row under each aid station name, put its mileage location. Make an abbreviated note if there’s something special about the aid station; in the example below, Wuflow says “(H2O)” because it’s a water-only stop, and No Name says “(bag)” because that’s the point where drop bags are available.

Next, use an online pace calculator (such as the one at coolrunning.com) to estimate your pace, and the time to each aid station. Fill in the third row with your aspirational goal pace to each aid station, and the bottom row with your base-level goal pace.

Based on my training level and past experience, I had an aspirational goal to finish that race in 9:30 or faster, and a base-level goal to break 10 hours. Consequently, I figured out the pace to each aid station for a 9:30 and 10:00 finish time, and filled in the columns accordingly, so the pace band looked like this:

If you are worried about meeting the cutoff times (that is, the slowest time to certain checkpoints along the route), then create one more row on the bottom where you can list the cutoff times for specific aid stations.

Choose the “Landscape” format to print the pace band in a long strip, and then use packing tape to cover the paper like lamination. Cut it and tape it around your wrist, and ta-da, you have a pace band. For 100K and 100-mile ultras, you should create two bands—one for the first half, another for the second half—because it is difficult to squeeze all the info into a single band that fits well around your wrist.

Using the pace band above inspired me to run to aid stations ahead of the time for a sub-9.30 finish, to meet my main goal; but I knew if I struggled and got off pace, I could gauge from the bottom row of numbers whether I could meet the base goal of a 10-hour finish.

Be careful, however, not to let your pace band frustrate you. When I raced the 2015 Tarawera Ultramarathon 100K in New Zealand using a pace band with split times to aid stations, it seemed to mock me midway through. I fell far behind my base-level goal pace because of the exceedingly challenging middle portion of the race. I didn’t know whether to laugh or cry when I looked at the pace band and saw how far behind I was from my estimates.

Two-thirds of the way through, however, the course changed drastically to runnable fire roads. I sped up considerably, and the numbers on the band motivated me to get back on pace. The final third of the race went so well that I met my top-tier goal, thanks in part to that pace band egging me on to catch up to the goal split times printed on my wrist.

10 Ways to Know You’re an Ultrarunner

At what point can you legitimately call yourself an ultrarunner? Arguably, you become an ultrarunner as soon as you run farther than 26.2 miles. But to really be an ultrarunner, in my view, takes a deeper understanding of the sport’s culture and a longer-term involvement with its community.

I posted a query, “You know you’re an ultrarunner when …?” on the Trail And Ultra Running Facebook page, and elicited several responses, some of which are printed below. I mixed in several of my own tongue-in-cheek replies.

You know you’re an ultrarunner when:

1. You start your morning reading UltraRunnerPodcast’s Daily News and iRunFar rather than mainstream news.

2. You say you “only” ran 20 miles last Saturday.

3. You follow twitter handles such as @asgarbagecan and @douchebagultra.

4. You think of December as lottery season, not holiday season.

5.You think of “qualifier” in terms of Hardrock or Western States, not Boston.

6. You know what leaves to wipe with.

7. Your goal is “sub-24 hours.”

8. You try not to scoff at 13.1 and 26.2 stickers.

9. You spend an entire Saturday hitting the “refresh” button on ultralive.net.

10. You plan childbirth around big races, not birthdays or holidays.