In 2005, one month before I turned thirty-six, i lined up for a marathon unlike anything I’d ever experienced, with runners unlike any I’d ever met.

My road-racing experience made me familiar with the crush of bodies standing in starting corrals in big-city races. I had felt the stress and thrill of ticking off 6:20 miles to get under forty minutes at a 10K, and I’d worked on breaking 3:10 at the marathon because I wanted to “BQ like a man”—that is, qualify for the Boston Marathon under the men’s standards for my age group.

This marathon, however, featured no starting corrals or pacing groups, no long lines, no purple Team-in-Training singlets, no rock bands, no balloon arches, and no earnest-looking runners doing strides to warm up for a fast start.

Instead, I encountered fewer than 150 people in an oak grove off a dirt road at the base of Mount Diablo, a double-peaked mountain that rises some 3,000 feet from its base and offers escape from suburban sprawl about 30 miles east of San Francisco.

These runners looked relaxed and checked out each other’s gear while asking about friends, family, and recent or upcoming races. Many wore bandanas around their necks—for wiping off sweat and getting wet to cool off—and fabric coverings over their shoe openings for keeping out dirt and pebbles. One bearded guy wore threadbare denim cutoffs and carried two water bottles with handles made from duct tape.

Snippets of conversation floated by that referenced depleting, “epic” runs.

I looked at my 20-ounce handheld water bottle with a tiny pocket that contained only two energy gels. Did I have enough water? Calories?

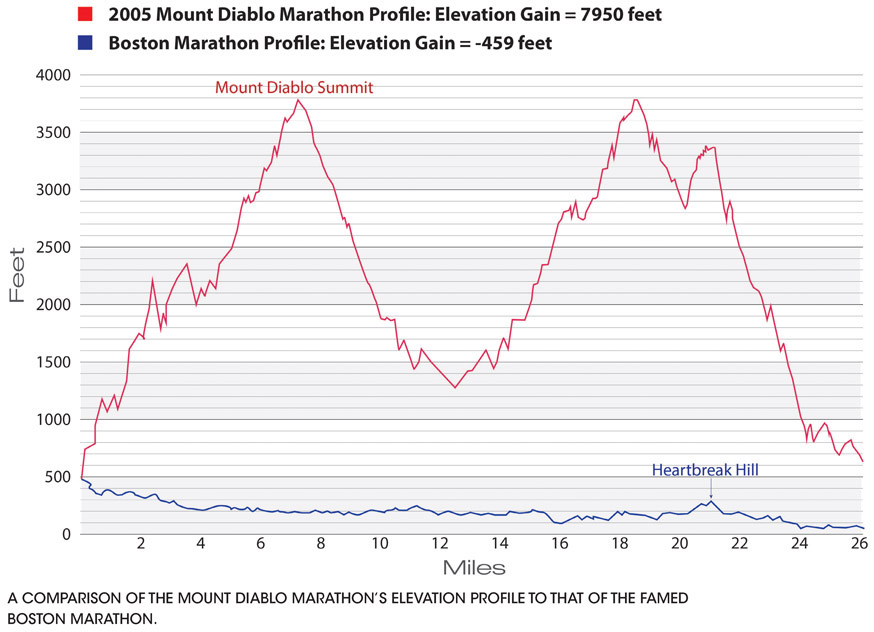

Accustomed to water stops every 2 to 3 miles in marathons, I didn’t give much thought to carrying water or food. But the day’s temperature was rising, and the first 5 miles up switchbacks looked like a monstrous climb on the course’s elevation profile.

A man with a bullhorn called people over to an open gate, which would serve as the makeshift starting line. He asked the group, “How many of you are doing the marathon?”

About one-third of us raised our hands, which generated polite applause.

“And how many of you are doing the 50-miler?”

A much louder cheer went up. Suddenly, being in the marathon felt like being in the kiddie pool—and I wanted to dive in and swim with the big kids!

Several runners deferentially lined up behind one person in particular—a tall guy with curly hair and a headband who stood a few feet away, smiling and gesturing for others to get up in front with him.

At that point, I realized I was starting a race with the country’s top male ultrarunner, Scott Jurek, the six-time winner and record-holder of the Western States 100-Mile Endurance Run. It turns out it’s typical at races like these for the so-called “elites” to hang out and start with the mid- and back-of-the-pack-ers, given the “we’re all in this together” vibe. Jurek was there to complete the 50-miler as a mere training run. (Two months later, he’d go on to win his seventh consecutive Western States 100.)

The race director briefly explained the course markers that we were supposed to follow, but I failed to pay attention because I was so in awe of being in the presence of Scott Jurek and so disoriented by the unceremonious race start.

Without warning or fanfare, the director counted down from ten to one and said, “Go!”

We all started running comfortably, many around me continuing their conversations. It felt more like a casual group run than a race. Should I go faster? Should I slow down? What was I doing running in plain view of Scott Jurek’s heels?

I had no idea how my first trail marathon would unfold, nor did I realize I was starting to follow a branch of the sport that would become my life’s passion.

I took up running almost by accident as a twenty-four-year-old graduate student, with minimal athletic experience as a teen or young adult. I had married my high school boyfriend, and we moved to Berkeley so I could get a master’s degree at the University of California while he started his career as an attorney.

Me, a runner? The girl who hated running the required two laps in PE? The one who, in college, smoked Camels and earned the nickname “burrito queen” because I ate a microwaved burrito from the 7-Eleven every day?

My life changed the first Sunday in March 1994 when I watched two friends finish a marathon. Could I do that? The next day I jogged 3 miles, a mile-and-a-half farther than I’d ever run in my life. I felt flush with pride and determination. Running provided a sense of accomplishment and wellness that I needed to counteract the feelings of inadequacy and anxiety that simmered while I was in graduate school. Pretty soon, I became determined to run a whole dang marathon.

At the 1995 Napa Valley Marathon—my first—I averaged a 9-minute/mile pace to finish just under four hours. I was hooked.

In the decade following that marathon, my chubby thighs gained strength and definition, while my lungs, weak from smoking a pack of cigarettes daily as an undergraduate, felt progressively stronger and turbo-charged.

I gave birth to our daughter in 1998 and son in 2001, worked as a reporter and editor, and all the while learned everything I could about road running. Each year revolved around 10Ks and half-marathons that built up to a goal marathon: Big Sur, Chicago, Portland, Los Angeles, California International, Boston. I thought that running 26.2 miles on pavement, and striving to shave a couple of minutes off my time, was the be-all and end-all of running.

During this period, however, something emerged on the periphery of my consciousness and led to that first trail marathon in 2005, which turned out to be another life-changing run.

That “something” was a group of hard-core runners who went farther than I could fathom, mostly on trail.

First, I met the Ann Trason, the fourteen-time winner of the 100-Mile Western States Endurance Run and an inspiration to legions of female trail runners worldwide. Ann lived and ran around our neighborhood near North Berkeley. I would be running a mundane out-and-back 5-miler along a paved road ringing Berkeley’s Tilden Park, and Ann Trason’s lithe body would pop out of a trail and wave hello to me. Later, I found out she ran 25 miles south through the regional parks, on an extensive network of trails I barely knew about, and then she ran back—all in a day’s training run.

I tentatively began to explore those trails on weekend runs, and met some legit trail runners—men and women (but mostly men) who didn’t care about marathons or track workouts as much as they did about long runs on trails.

On runs and at parties, these runners dropped the names of characters like Tropical John, Speedgoat Karl, Karno, and The Rocket.* They bantered about events such as HURT and AR50. I didn’t know who or what they were talking about but, like an anthropologist studying a tribe, I made mental notes of the details that this subset of runners revealed.

Later, at home, I researched the snippets of information gleaned. I started reading UltraRunning and Trail Runner cover to cover. Long before I became an ultrarunner myself, I became a student of the sport.

Meanwhile, Mount Diablo beckoned. I once ran 13 miles up to the summit, on the paved road, and then got a ride back down in a car—a fact that seems ridiculous now that I’m intimately familiar with the trails to the summit. The paved road is meant for cars and bikes. But, back then, I thought the best route up was the smoothest and most direct. I viewed the uphill half-marathon as a killer cardio workout, not a mountain adventure.

Then I signed up for a half-marathon on some trails that skirted Mount Diablo. I had no idea how to pace a race on dirt with an undulating elevation profile that gained over 1,000 feet. I simply went hard from the start and pushed to the upper ranges of my heart rate for all 13 miles—and to my astonishment, I won. Yes, won. There’s a first time for everything, right? My time was slow compared to my half-marathon road times—one hour, thirty-eight minutes—but the pace proved speedy by trail standards.

Cooling down at the finish line and soaking in the blissful feeling of a strong finish, I couldn’t help wonder: Could I do a marathon here, all the way to Mount Diablo’s summit?

And that’s how I found myself chasing Scott Jurek and other 50-milers in the marathon division of the 2005 Pacific Coast Trail Runs Diablo Marathon—a small, regional event that, like my first-ever 3-mile run in 1994, proved to be a milestone in my evolution as a runner.

The dirt fire road, bordered by manzanita and oak-bay woodlands, steadily climbed, and the runners around me downshifted to a hike. I copied them, swinging my arms and trying to match their pace. Instead of feeling guilty about walking, I realized that hiking in a race like this was the smartest, most efficient thing to do—and it felt good! It stretched out my calf muscles and Achilles tendons, and it kept my heart rate in a sustainable zone.

I stopped caring about the fact that my pace averaged only around 14 minutes per mile on the uphill. I felt liberated from my watch while running more by feel than by time, and I savored this powerful lower gear.

Some 5 or 6 miles up the mountain, we came to the first aid station. A folding table covered with sweet and salty snacks, and liters of Coke and ginger ale, greeted us, staffed by a couple of volunteers who helped runners refill their water bottles. Everyone took time to chat, crack jokes, and thank the volunteers. No one rushed through or grabbed a cup and threw it on the ground.

Feeling hungry, thirsty, and hot, I savored the buffet of goodies and let my cravings be my guide of what to eat. My eyes locked on a paper plate of cut-up PayDay candy bars. I never eat junk like that. But the gooey mix of peanuts and caramel seemed to ignite a primal urge. I grabbed a chunk of PayDay, wolfed it down, took some swigs of Coke, refilled my water bottle, and thanked the volunteers.

The PayDay bar lived up to its name, because five minutes later, I felt like a million bucks. Cruising on a ridgetop fire road, I took in the view of windswept grasses that covered rolling hillsides, which spread out toward the cityscapes and, all the way on the horizon, to the blue of San Francisco Bay. The scenery, mixed with the sugar intake and endorphin rush, made me feel literally and figuratively high, as if I were soaring toward the summit like one of the hawks that circled the peaks.

The trail snaked upward past jagged rock outcroppings, so once again I downshifted to hiking. I was unsure of how many miles I had covered, or what my pace measured, or where I was in relation to the other marathoners—but I didn’t care. Instead, I experienced a mix of feelings that I couldn’t recall in any recent road marathon: Joy. Wonderment. Excitement. Discovery!

I spotted the radio towers marking the summit. So close, yet so far! Just getting to the top felt like a victory, even if I was only halfway through the race.

Reaching the parking lot at the summit, my water bottle empty again, I hungrily greeted a couple of guys manning the aid station and thrust my grubby fist toward another pile of PayDay bars. I felt like a grizzly bear that emerges from hibernation with pent-up energy and a voracious appetite.

“Hey,” said one of the guys, “first woman up!”

I stopped my double-fisted food shoveling and Coke swigging to sputter, “No way! Are you joking?”

“Yeah. A couple of the guys in the marathon and 50 went through, but you’re the first woman we’ve seen.”

Gulp. I felt a twinge of competitive pressure, as if I should drop everything and run to keep the lead. I had felt free from such pressure on the climb to the summit, when it was just me versus the mountain, and I wanted to keep having fun. So I deliberately lingered a little longer to talk with those dudes and admire the summit’s views. Thanking the guys, I ran off with a handful of trail mix to top off my tank.

The trail’s footing turned to loose rock, which my shoes slipped and scuttled over. In some places, the trail became so narrow and overgrown with scratchy brush that I couldn’t see my feet. I just had to plow through the clawing branches and take extra care not to catch a toe and trip.

I imagined what my seven-year-old daughter and four-year-old son would say if they could see my dirty, scratched-up legs and sweat-streaked face, and I laughed out loud. They’ve said it before: “Mom, you’re cray-cray!”

Exhaustion mixed with elation, along with being solo on this relentless trail, made me feel increasingly loopy. With no one around to hear, I burst out singing the commercial jingle from childhood that got stuck on repeat in my head when I ate the candy bar at the aid station: “Sometimes you feel like a nut, sometimes you don’t! Almond Joy’s got nuts, Mounds don’t …”

As the downhill became progressively steep and challenging, I put a lid on the silly song and single-mindedly focused on not falling. Never had I tried to run down something so rugged. I leaned back and eased down rocky chutes that seemed as steep and slippery as a playground slide, grabbing branches to steady myself.

Suddenly something flew into the corners of both eyes and landed on my tongue. Rapidly blinking and gagging, I saw a small cloud of tiny black dots in front of my face, then felt those black dots all over my eyes, ears, arms, and legs. Gnats!

The disgusting swarm of miniature flies blindsided me. I stopped and ridiculously waved my arms, spat, rubbed my eyes, and stripped off my shirt. Shot full of adrenaline, I took off running with fearlessness on the downhill and heard myself singing again, “Sometimes you feel like a nut …”

The midday sun beat down, and I drained my bottle. My watch showed that I had been going for over four hours. Four hours?! That’s longer than my slowest-ever marathon, and I doubted I was even near Mile 20.

A sound in the bushes on the hillside above made me look up. I half expected to see a deer bounding, but instead glimpsed long, brown hair flowing and outstretched arms windmilling through the air. A woman gracefully galloped down the mountain, running over the rocks as smoothly as water flows downstream. Her numbered bib indicated she, too, was in the marathon.

I moved to the side to let her pass. “Good job!” I said with genuine admiration.

“Thanks!” she said, beaming.

I had just relinquished the first-place position, but watching this younger, more skilled woman’s grace and gutsiness made me more inspired than disappointed. I resolved to try to follow and copy her style, as if she were a guide more than the competition. I wanted to emulate her intrepidness and smoothness.

An hour later, we reached flatter terrain on foothills. I lost sight of the lead woman. I lost track of time. All I could muster was a slow jog in granny gear as my skin crisped in the sun and my mouth became parched.

Five hours had passed—much longer, in terms of time, than I had ever run before. Not knowing where the finish line would be, I made myself pick a point in the distance and commit to run to that point without stopping or walking.

“Just make it to that tree … just make it to that course ribbon … you have to finish … you will finish.”

I fantasized about lying down and guzzling cold drinks at the finish line. I was struggling to survive the most challenging marathon of my life. To finish would be to win, regardless of my place.

Finally, I spotted the curve in the canyon and the grove of oaks where we started the race that morning, which seemed like eons ago. The prospect of the finish breathed life into my legs.

Speeding up, another feeling kindled in my chest: that of pride. I had gone all the way up to the summit and back down, for the first time ever, and as hard and as fast as I could! No mere marathon, this had been a test of mental and physical fortitude far more challenging, dramatic, and adventurous than anticipated.

With no one around to watch, I sprinted past trees and bushes in the final stretch and felt more heroic than when I ran past throngs in the final mile of the Boston Marathon. I burst over the finish line with a grand total of about a dozen people watching—the handful of guys who’d finished the marathon, the woman who beat me, the race director, and some volunteers. They applauded and greeted me as if I were a star. The race director hugged me. I high-fived the first-place woman and told her I thought she was amazing.

A communal picnic ensued. A cooler full of beer beckoned. I could get used to this, I thought, feeling profoundly satisfied from the hard effort and camaraderie. But doing the 50-miler? That’s truly insane!

When I crossed the finish line, the clock read 5:23. Two hours slower than my typical marathon. But in many ways, it was my best marathon time to date.

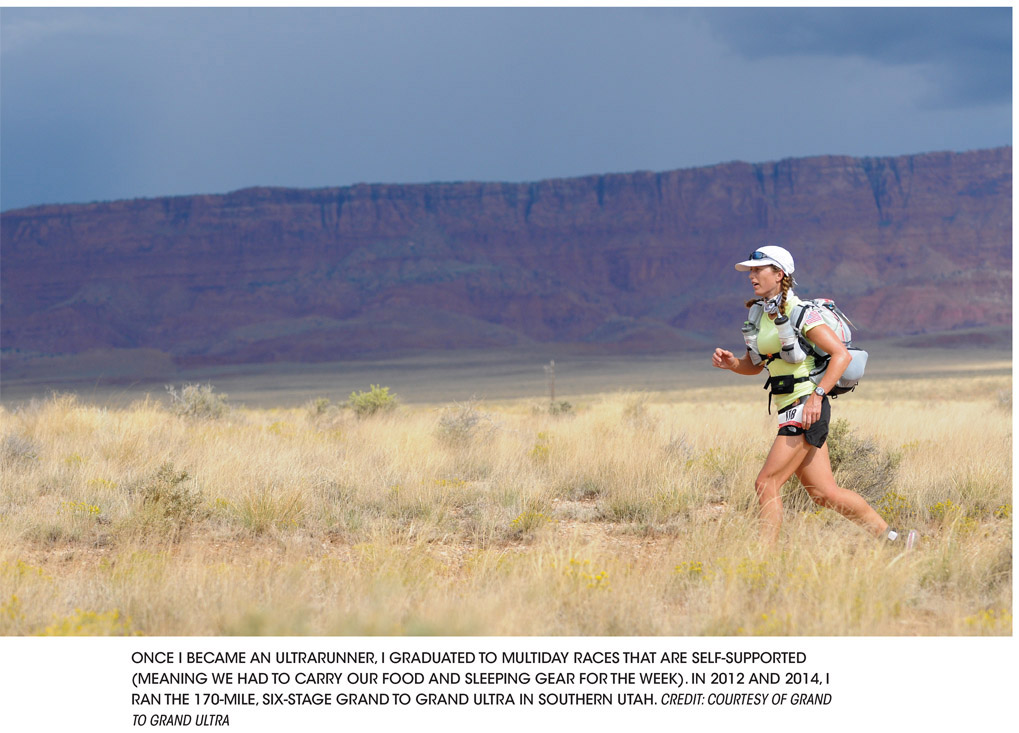

In the decade following that first trail marathon, I ran a handful of other trail marathons and then graduated to the 50K. The 50Ks became 50-milers, then 100Ks, and then a couple of multiday, self-supported, 170-mile races. Eventually I took the plunge into 100-milers.

I didn’t let go of road racing completely. I returned to the Napa Valley Marathon in 2009 and ran a personal record (PR) in 3:05, and I still run on the roads around our neighborhood throughout the week.

But my heart and legs feel more at home on the trails. I found that trail running feels more peaceful and less pressured. More interesting and less tedious. More humbling, awe-inspiring, and adventurous, and less prone to injury.

I also discovered that trail running seems to nurture the very traits that psychologists and child development experts say lead to success and fulfillment in life—characteristics that, as the mother of two teens, I try to model and instill in my kids. These traits include risk-taking, flexibility, humility, respect, patience, mindfulness, empathy, resiliency, and grit.

Simply put, running long distances on trails made me a better runner—and a better, happier person.

That’s why I wrote this book: To guide others toward this discovery of better running—and better living—through trail running.

Who This Book Is For

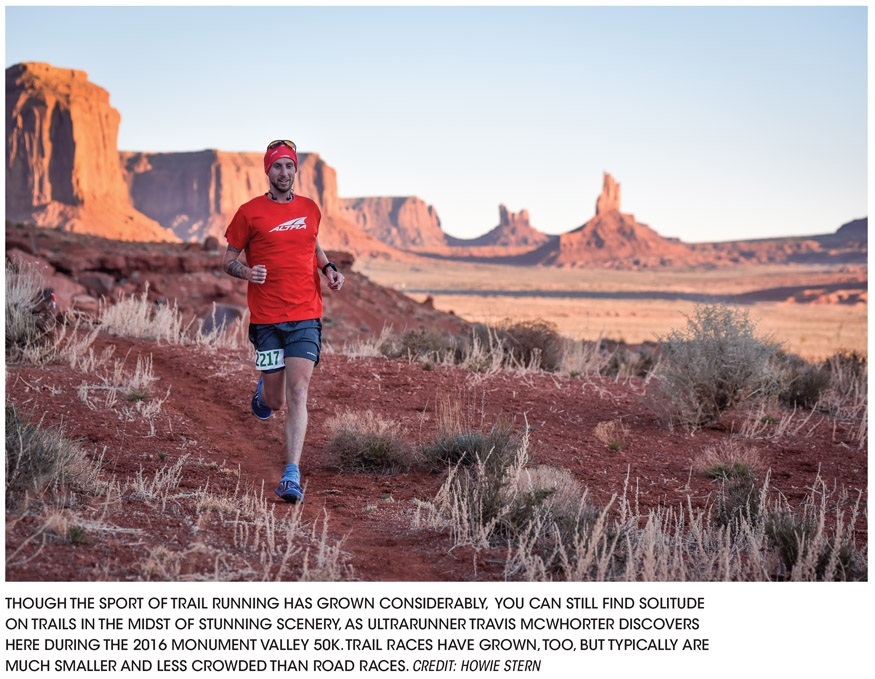

In the decade-plus since I took up trail running, the sport has experienced significant growth. The Sports & Fitness Industry Association counted over 8.1 million trail-running participants in 2015, an 8 percent increase over the prior year. Since 2010, the sport has had an annual average growth of 10.4 percent.1

In spite of this growth, most trails are not crowded. You can find trails where you can run for miles and not see another soul. Although some popular trail races fill up quickly or employ a lottery for entry, the sport is open for anybody—and by that I mean any body, of almost any size or age.

I wrote this book for people new to the sport, as well as for experienced runners who seek to improve their skills or try new adventures on the trail. The chapters are organized progressively, from what you need on day one to become a trail runner, to what you need to build your base and develop trail-specific skills, to what you need to stay safe and healthy, and finally, to what you need to successfully race shorter and ultra-distance trail races. A specific goal anchors each chapter.

Thank you for reading The Trail Runner’s Companion. I hope the following pages fill you with energy and desire to find a trail and break into a run, and I hope they empower you with the know-how to successfully complete virtually any trail-running challenge.

Chances are, each trail run will affect you and, over time, subtly change you for the better.

Footnote

* Tropical John is John Medinger, who holds many influential positions in the sport, including longtime publisher of UltraRunning magazine and president of the Western States Endurance Run board. Speedgoat Karl is Karl Meltzer, winner of the most 100-milers ever and a well-known race director. Karno is Dean Karnazes, a standout in ultrarunning whose 2005 bestseller Ultramarathon Man attracted countless newcomers to running in general and to trail/ultra running in particular. The Rocket is Errol Jones, a well-respected ultrarunner from Oakland who has been racing, pacing, and race directing for several decades.