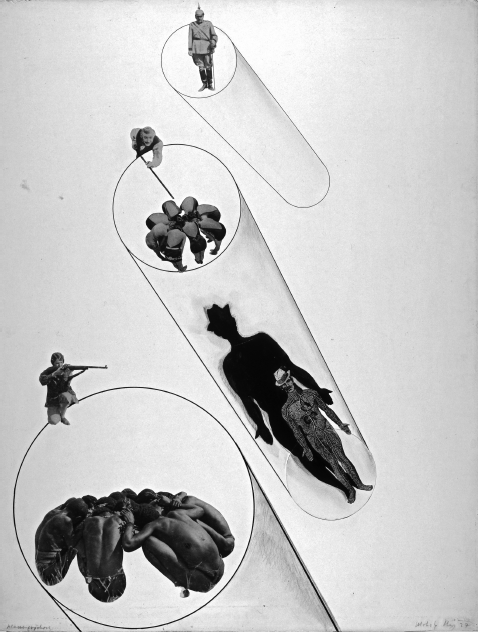

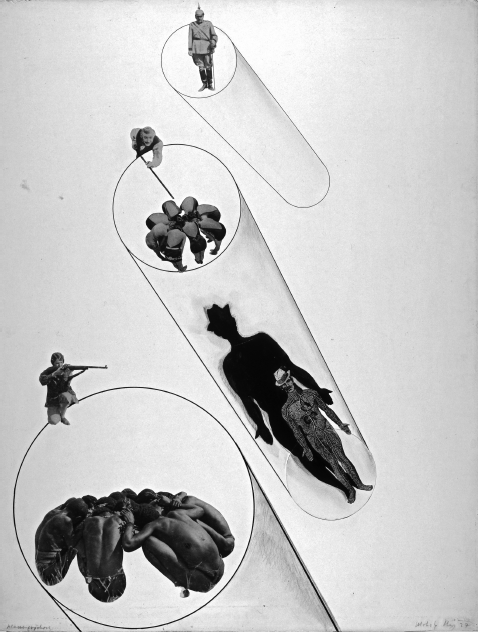

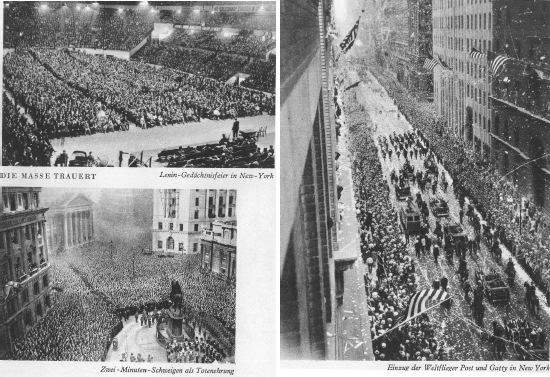

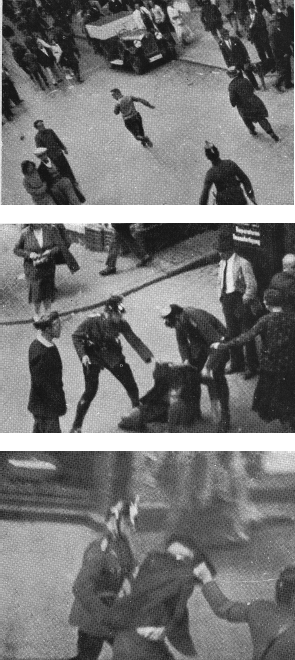

The same year as Vienna’s crowds set the Palace of Justice on fire, in 1927, Hungarian artist László Moholy-Nagy offered a graphic illustration of the idea of the masses that many Europeans subscribed to in this period. The image has come down with two alternative titles:

Massenpsychose (Mass Psychosis) and

In the Name of the Law. It is one of Moholy-Nagy’s photoplastics, a mixed-media form he developed while he was teaching at the Bauhaus school of architecture and design (

figure 4.1).

1Moholy-Nagy emphasized that the photoplastic image portrays “concentrated situations” that can be developed instantaneously through associations.

2 An Eskimo would be unable to understand a photoplastic sheet, he claimed, because the image speaks to viewers accustomed to an urban world characterized by the compression and simultaneity of objects and events.

3 The photoplastic image teaches such viewers to perceive the relationships structuring their world. The image, Moholy-Nagy said, “is directed towards a target: the representation of ideas.” To this end, the title is crucial. “By means of a good title a picture’s grotesque or absurd entirety may become a sensible, ‘persuasive truth.’”

4

What’s then the truth revealed by the title of this image,

Massenpsychose or

In the Name of the Law? Moholy-Nagy stated that the photoplastic scene is a condensation of an idea. He asserted that whole acts of theater or film could be compressed into a photoplastic scene.

5 Following his hint, we may see

Massenpsychose as a diagram of the influential theory of mass psychology. By implication, the image also addresses the general discourse on “the masses.”

The relationships in

Massenpsychose are hierarchical. The pool player masters the female swimmers. The female gunslinger controls the Africans in her own cylinder and the male figure in the adjacent one. The general stands at the peak of the pyramidal structure, governing the field as a whole. The positions of dominance are thus occupied by individuals with recognizable faces. The positions of subordination, by contrast, are held by faceless females and Africans. Moholy-Nagy portrays the latter in accordance with the principles of mass psychology: human subjects who form a crowd lose their individual identities, claimed the founders of mass psychology, Gustave Le Bon and Gabriel Tarde, as well as Georg Simmel, Sigmund Freud, and their followers in the interwar period. This is because people in a crowd are eager to conform, obeying the laws of “imitation” as Tarde argued, or “contagion” which was Le Bon’s term for the same concept. What results from this psychic chain reaction is a collective agent behaving like a “decapitated animal,” as Henry Fournial argued, or a “wild beast without a name” which was Gabriel Tarde’s expression.

6Moreover, we see that the individuals occupying the positions of dominance are carrying phallic objects. These objects signify the traits that characterize a leader. Metonymically linked to the king’s scepter and the magic wand, the cue, the sword, and the rifle are signs of the leader’s charismatic power, the instrument of suggestion with which he manipulates the sentiments of the masses. “A crowd is at the mercy of all external exciting causes” Le Bon stated. The crowd is “the slave of the impulses it receives” or “a servile flock that is incapable of ever doing without a master”

7 Apparently,

Massenpsychose offers a view of a social world split between ruling leaders and subjugated collectives. The image also shows the manipulatory nature of the relation obtaining between the two.

The bonds that bind persons to a crowd are always emotional in character, argued the theoreticians of crowd behavior. The affects that govern a crowd scrape off the individual’s layer of cultivation and reason, making him or her conform to the lowest common denominator of the group, the base instincts of the unconscious. This process is also captured by Moholy-Nagy’s photoplastic. Consider the man with the giant shadow at the bottom of the second cylinder, locked at the intersection of the trajectories of the bullet, the billiard ball, and the thrust of the sword. What remains of his civilized being is just the hat. The rest—his entire body—has lost the skin of cultivation that shelters individuality. A shadow is a conventional symbol of the subject’s unconscious passions. This may be the accurate reading here, for it conforms to the central thesis of mass psychology: in the crowd, the subject is subdued by his impersonal instincts. His individual identity is overshadowed, and he merges with the faceless

bête humaine represented by the females and the Africans, who would thus correspond to Freud’s primal horde.

Finally, the transparent cylinders, resembling test tubes of a chemical laboratory, suggest that

Massenpsychose also portrays the methodology of mass psychology.

8 Gustave Le Bon stated that the transformation occurring in a crowd is comparable to what happens in chemistry as certain elements such as bases and acids are brought into contact and combine to form a new compound.

9 The French historians and sociologists who inaugurated the analysis of the crowd modeled their studies on the natural sciences, branding their newly parceled out domains with names such as “social physics,” “social statics,” and “social dynamics.” They understood the social field in terms of psychological charges of interacting social atoms that could be measured by a neutral scientist. Hippolyte Taine, the first true historian of the crowd, wanted to explain the evolution of French society through such a chemistry of passions. Just as the chemist analyzed the contents of his test tubes, so Taine examined society. In this spirit he concluded, famously, that the psychological forces manifested in history are comparable to chemical compounds: “Vice and virtue are products like vitriol and sugar.”

10With just a few carefully organized images and lines, Moholy-Nagy’s work thus captures the idea of the masses underpinning the disciplines of mass psychology and mass sociology. By revealing the nature of this idea, Moholy-Nagy’s image asks the viewer to take a closer look at it. In representing the way in which the discourse of mass psychology represents society,

Massenpsychose thus exhibits the ideological message of this discourse and invites the observer to pass judgment on it. By extension, the image discloses the oppressive agency operating “in the name of the law,” being, of course, the same oppressive agency that operates in the name of “mass psychology.” It would therefore be wrong to call Moholy-Nagy’s

Massenpsychose a representation of the psychology of the masses. Rather, it is a representation of mass psychology as a discipline of knowledge and power.

From the 1890s onward, mass psychology and mass sociology had turned the masses into an object of investigation. Now, in 1927, Laszló Moholy-Nagy reverses the perspective and turns mass psychology into an object of examination, evincing the ideological character of its view of society.

If a certain discourse that once structured the prevailing perception of society is transformed into an object of perception or is revealed as an ideology, this seems to indicate that the legitimacy of that discourse has diminished, or else it would not be possible to think outside it, much less post it onto a board for public display. Evidently, Moholy-Nagy’s image records such a transformation in the dominant conception of the masses. As I have stated, the meaning of “the mass” changed profoundly between the inaugural moment of French crowd psychology in the 1890s and Germany and Austria of the 1920s. The transformation did not entail that there was less talk about the masses nor that there was more clarity on the issue of the masses. On the contrary: more talk, less clarity. To enter the cultural landscape of interwar Germany and Austria is to encounter competing views, theories, and images of crowds.

How should we understand that Moholy-Nagy’s

Massenpsychose features a rifle-woman taking aim and a group of women in swimsuits? Portraits and narratives of collectives in the 1920s entailed a reshuffling of the gendered categorizations of the crowd, a topic I have so far only evoked but now must elaborate in some detail as it partly explains the emergence of what I have called the post-individualistic notion of the masses. In its early versions, for example, in Le Bon, mass psychology asserted that the masses are of feminine nature, a subservient and malleable matter, in relation to which the leader exercises his powers.

11 Similarly, Werner Sombart stated in 1924 that the masses “have an ‘irrational,’ feminine predisposition”

12 By rejecting the conception of individuality as a subject position that is external to the masses, many of the writers I have discussed also refuted the sexual ontology that ascribed masculine qualities to the leader-individual and feminine ones to the masses. This transformation may be related to the conferral of suffrage to women in November 1918 and the general consolidation of the women’s movements in the interwar period as

die neue Frau (the new woman) became symbol of a constituency that was not reducible to any of the conflicting classes in the social struggle.

13The women’s movements pressed for a more multilayered interpretation of society than conventional class analysis could offer. In this context, the figure of femininity was often evoked as a political subject or an ideological and aesthetic fantasy able to transcend the dualistic framework that split the social body in individual citizens and proletarian masses. Interestingly, two emblematic Weimar dramas, Ernst Toller’s

Masse-Mensch (1919), which I discussed in chapter 2 (

section 18), and Bertolt Brecht’s

Die heilige Johanna der Schlachthöfe (1927; translated as

Saint Joan of the Stockyards), follow this pattern, and it applies to the heroine in Fritz Lang’s

Metropolis as well (also discussed in chapter 2,

section 12). All three stage a violent antagonism between the anonymous masses and a group of capitalist individuals. All posit a female hero as a mediatory figure in this struggle: in Toller’s play she is called

Die Frau (The Woman); in Brecht, Johanna; and in Lang, Maria. These heroines are personifications of the dehumanized collective. Their solidarity is without limits. In her prophetic dream, Johanna sees herself at the head of all the protest marches and uprisings of human history.

14Mediating between the dehumanized masses and not yet existent institutions of political representation and citizenship, these female leaders seem to be symbolic manifestations of the real dilemma of constituting the gendered female subject as a citizen of the democratic republics of interwar Germany and Austria. As the women’s movement triangulated the political struggle, it constituted a force that was assimilable neither with the disenfranchised proletarian masses, nor with the stereotypical individual

Burgher. Johanna, Maria, and The Woman thus reflect a collectivity that becomes visible if we attend to the gender dimensions of the opposition between the figure of the masses struggling to attain citizenship and the figure of the individual citizen struggling to retain his power to represent society. Always partly occluded and suppressed by this dominant axis in the social and political struggle, female agency as embodied by these heroines offers a third alternative of representing the social body, one that we must not identify either with the proletarian revolution as envisioned by the communist parties nor with right-wing authoritarianism.

Yet Johanna and The Woman—and the alternative they bring to life—are somehow too good for this world, as Brecht would have said. They are utopian figures, symbols of a social-democratic reformism, egalitarian republicanism, or humanist universalism that bears no relation to the fractured political reality of Weimar Germany. This lack of firm anchorage in the real political sphere may explain why both dramas have recourse to the nineteenth-century practice of allegorizing the nation and the people as a feminine figure. Like Marianne, the allegory of the French people, or Germania, her German equivalent, Johanna and The Woman appear as the

corpus mysticum of the people, redeeming the antagonisms that destroy the

corpus politicum of male society. On a structural level, then, Lang’s, Brecht’s, and Toller’s heroines, notwithstanding their socialist convictions, are akin to “the great German mother,” the allegorical mother of the nation through whom conservative segments of the women’s movement and fascism itself sought to represent the German tribe. This is by far most evident in the case of Lang’s Maria. Explicitly identified as the “heart” mediating between the “hands” of the working masses and the “brains” of the elite, she comes across as a hyper-idealization of this figure of femininity—while her bad double, the robot-Maria, comes across as a caricature of the female rabblerouser.

15Unlike the fascist figure of femininity, however, these heroines fail to represent the collective. By foregrounding these failures, Brecht’s and Toller’s plays problematize the inherited principle of representation, according to which the masses is a force of potentiality that must be mobilized by the leader or the vanguard party. While Maria, as we have seen, is split in two, embodying the dual nature of political passions, or what Theodor Geiger saw as the destructive-constructive couplet of the proletariat, Brecht’s Johanna and Toller’s Woman shift positions as the revolution unfolds—now assuming the role of the individualized leader, now embracing the anonymity of the movement, now emerging as negotiators between the struggling classes. Yet they always end up betraying the collective they wish to serve, which is also the case as the evil Maria usurps the leadership of her good double and destroys what she has accomplished. Such is also the tragic kernel of Toller’s and Brecht’s dramas: although The Woman and Johanna are initially situated as mouthpieces of the people, neither dispose of the forms—that is, the rhetoric, the organization, the revolutionary strategy, the institution—by which they could represent the people politically. If we read these texts as efforts to address the critical problem that haunted Weimar society—how to represent society politically and culturally—we must conclude that they fail to project an image of democracy, that is, a form of representation that does not define itself in opposition to an excluded majority branded as “the masses.” However, it is precisely through this failure that they disclose their truth as political dramas, in the sense once summarized by Heiner Müller: the task of political theater is not to invent new possibilities but to demonstrate the impossibility of reality.

16 The political truth that they express is precisely what Kathleen Canning has identified as the real predicament of women’s problematic and incomplete accession to citizenship in Weimar Germany. Political reality—notably, the articles on marriage and property in the new Weimar Constitution—made it impossible for them to acquire citizenship on the same terms as men.

17However, what turned out to be politically impossible was at the same time aesthetically productive and revealing. Masse-Mensch and Die heilige Johanna der Schlachthöfe each stages a collective that blurs the distinction between individual and mass, at the same time questioning the gendering of society in terms of masculine and feminine qualities. Placing a woman at the head of the revolution, the dramas illustrate the post-individualistic figuration of the masses that characterized a crucial part of Weimar culture. This figuration entailed a conception of political and cultural representation that went beyond the sterile opposition of individual and collective, as well as the false political alternatives of authority and anarchy, issuing instead in a republican egalitarianism in terms of both class and gender and a public sphere consisting of neither (feminine) masses nor (masculine) authority.

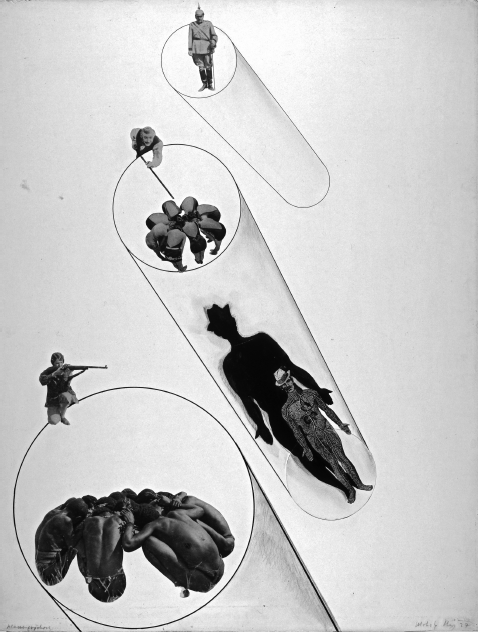

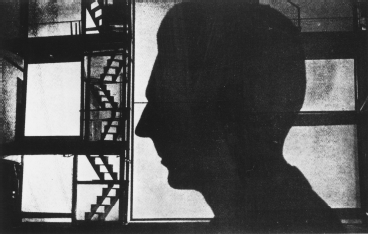

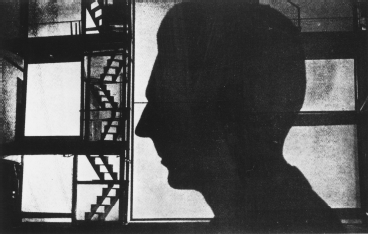

The Weimar artist Marianne Brandt also visualized a woman placed at a vantage point of historical insight and vision. Brandt was a coworker of László Moholo-Nagy at the Bauhaus school, where she enrolled as a student in 1923 and four years later was hired as leader of the metals workshop, and in the art of photomontage she showed exceptional compositional skills. One of her montages, made in 1928, is called

Es wird marschiert (

On the March) (

figure 4.2). It depicts a mundane, modern, and emancipated young woman—an allusion to the stereotype of the urban

Garçonne—who is leaning her head in her hands while the whole world appears to be spread out on the café table on which she is resting her elbows. This world is represented by press photographs of masses, carefully cropped and crammed together or piled on top of one another in the picture—masses of boats, masses of buildings, and masses of human bodies, most of which are marching and demonstrating left and right across a cut-up panorama containing elements from Europe and Asia. The woman is poised above this bustling historical momentum and is contemplating the mass movements that occupy the social space she surveys. Her gaze appears at once analytical and melancholic, and the composition of the montage turns this gaze into an extension or representative of a public gaze, which is able to survey and critically assess contemporary world affairs. The title,

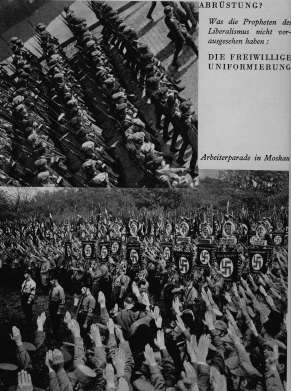

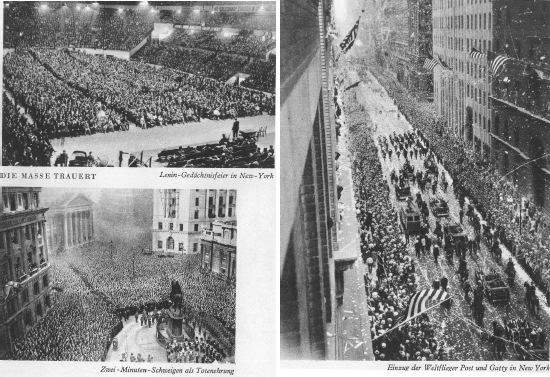

On the March, indicates the content of her assessment: everything in the world that she contemplates from her elevated position suggests that politics and history are increasingly dominated by uniformed masses and militarism.

18

Brandt invites her viewers to behold the world through the eyes of a personification of the new woman. These eyes see a world dominated by crowds, a world that is comparable to what was put on display in the image by Brandt’s colleague László Moholy-Nagy,

Massenpsychose, to which we may now return. Using Brandt’s montage as interpretative key, we understand how Moholy-Nagy’s photoplastic also draws on and subverts a preexisting coding of masses as female and social authority as masculine. Curiously,

Massenpsychose places the figure of femininity at both sides of this opposition: it is linked both to the subdued masses (the faceless female swimmers huddling together in their circular collective) and to the sovereign leader (the armed woman is a picture as good as any of dictatorial potency). Needless to say, these figures do not add up to one coherent feminine ideal but rather belong to contradictory registers.

Importantly, Brandt’s photomontage also provides an additional perspective on the masses, which is illustrated by Moholy-Nagy’s image as well. Offered by Es wird marschiert is a representation not just of mass society but also of a subject—the Garçonne at the center of the image—who is observing mass society and forming an opinion about it, thus serving as a representative of an implied public. Hence, she is not so much a flâneuse as a wholly new kind of authority. In Moholy-Nagy’s image, the position and perspective of this subject is not present in the visual material as such but only in the image’s mode of address. Like Brandt’s Es wird marschiert, Moholy-Nagy’s Massenspychose allows us to see the discourse on “the masses” from two different historical perspectives at once. On the one hand, we stare at the content of the images: a social hierarchy with firm boundaries between individual leaders and masses. To be sure, such was the image of society presented by mass psychology and mass sociology, from Tarde to Freud and from Le Bon to Hitler, and deeply entrenched in European society of the period. On the other hand, we may reflect upon the images’ public mode of address. The implied spectator of these photoplastic pictures has acquired such a high level of “literacy” in mass-psychological matters that he or she—like Brandt’s new woman—could be counted on to decode, almost instinctively, the meaning of the photoplastic constellation. The images invite this public to reflect on mechanisms of power, on the relation between leaders and subjects, between male and female genders, and between individuals and masses. That is, they invite a perspective of precisely the kind that Brandt offers by inserting the female figure at the center and endowing her with panoptical vision.

By consistently employing such a dual focus, Moholy-Nagy’s image thus turns into a condensation of the entire discourse on the masses, from its inception in France in the 1880s and 1890s to the transformations it underwent in the Weimar Republic. His image contains the trajectory traversed in this book, from the view proposed by mass psychology, that the mass was the opposite of individuality, organization,

Bildung, masculinity, reason, and other laudable human qualities, to a variety of views according to which the mass possessed its own internal dynamics and rationality. If there had once been a relative consensus as to what the mass was, how masses were shaped, and why masses dominated society, it had disappeared by the 1920s.

Moholy-Nagy also argued that photoplastic images constituted a new visual language, suitable for all kinds of public uses, from commercial advertising to radical propaganda. From this perspective, Massenpsychose as well as Brandt’s Es wird marschiert become critiques of the dominant, individualistic notion of “the masses” and they suggest an alternative, post-individualistic way of representing society. In sum, the public—or the common public sense, the sensus communis—that these two images address is a negation of the society depicted in the images themselves. Activating a social contradiction, Moholy-Nagy and Brandt provide visual representations of a society divided between leaders and masses while, at the same time, through their mode of interpellation, they institute a public culture without either individuals or masses.

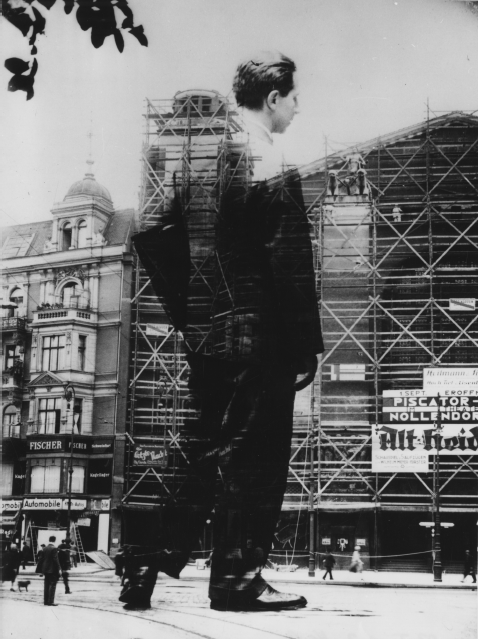

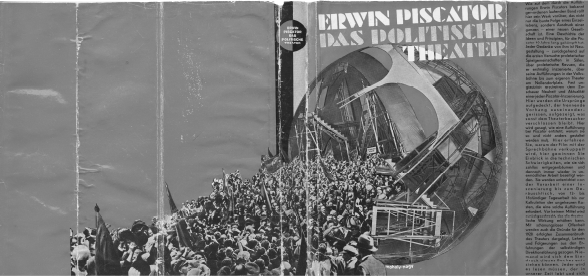

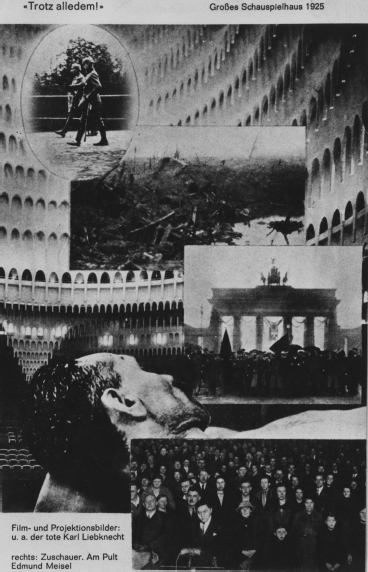

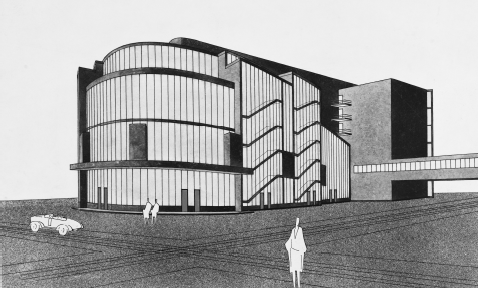

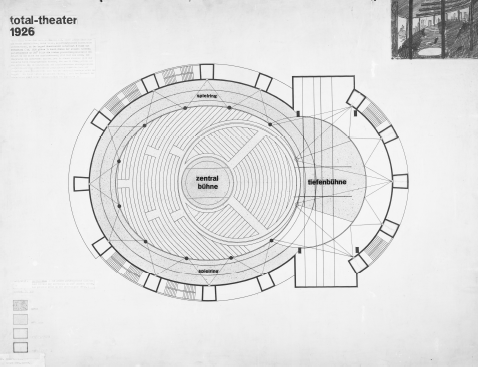

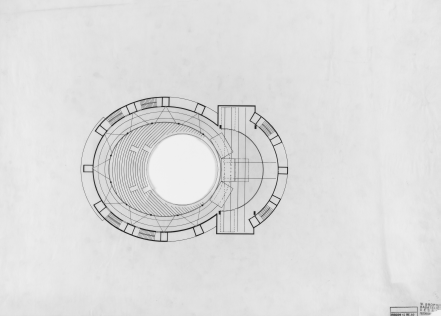

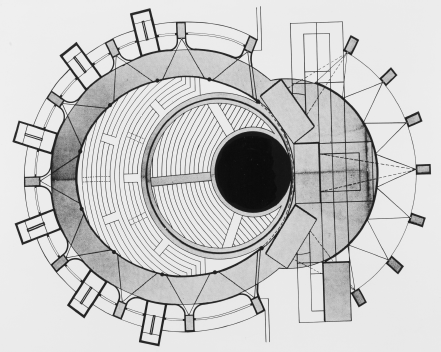

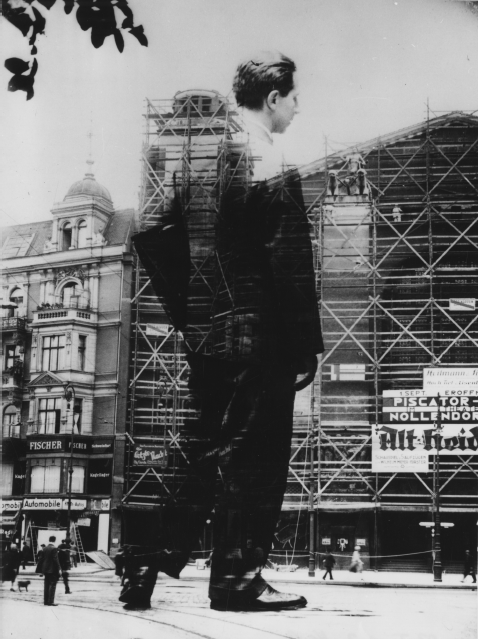

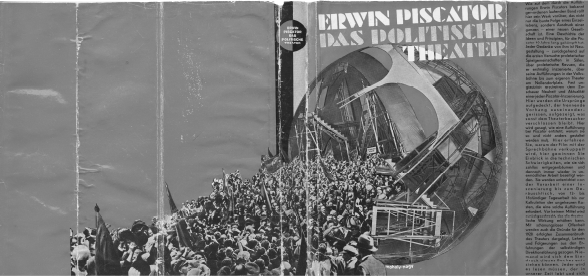

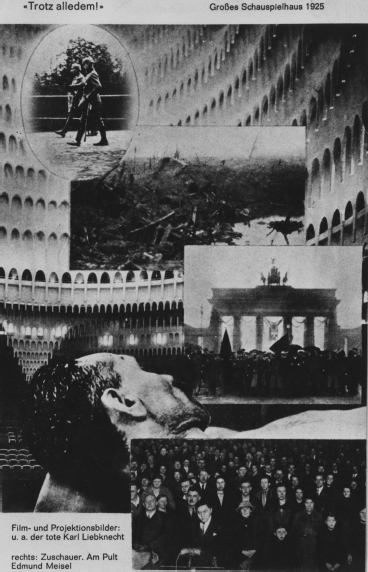

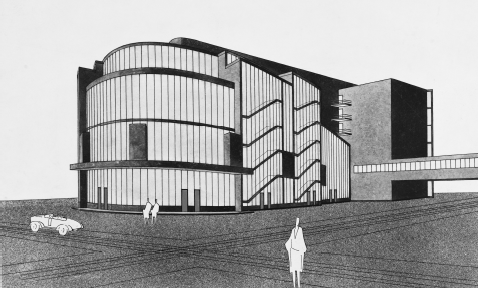

What such culture entails may be roughly gauged in another interesting image by Moholy-Nagy from the late 1920s (

figure 4.3). It is provisionally named

Up with the United Front (

Hoch die Einheitsfront), a title borrowed from one of the banners carried by the people in the crowd that is shown in the photograph. Unlike the carefully calculated compositions of

Massenpsychose and

Es wird marschiert, this picture gives an impression of rawness and incompletion: it comes across as a snapshot taken from within the crowd. Are there any individuals in this photograph? Are there any masses? The image depicts something else, a many-headed social agency that cannot be reduced to any of the two categories and which is neither disorganized, nor fully organized. Rather, this collective agent is abiding in a state of frozen mobility. The title evoking a united front is paradoxical, for if there is anything missing from the depicted crowd, it is unity. A disunited unity? What Moholy-Nagy shows are people conquering the public square and the social stage, instituting, as for the first time, a vocal and multifarious public culture.

In this way, the visual works of Moholy-Nagy and Brandt trust the viewers’ ability to undo the dichotomy of individuals and masses and to project themselves in a utopian direction, beyond those mechanisms of power that split the social field into a set of individual leaders and a faceless mass. They thus help outline the contours of a new public sphere of political and cultural representation while at the same time conjuring up the collective subjects and the subject of collectivity that are needed to make this arena a truly democratic one. This is also why Moholy-Nagy’s and Brandt’s works, along with the photoplastic technique they illustrate, are exemplary cases of Moholy-Nagy’s general constructivist program. As he argued in his article “Constructivism and the Proletariat” constructivism “is the socialism of vision—the common property of all men.”

19

Walter Benjamin, too, promoted a socialism of vision. In major writings from the late 1920s and throughout the 1930s he explored how contemporary modes of aesthetic representation and visual perception referred to “the collective,” just like the culture of an earlier era expressed a social life organized around “the individual.” In Benjamin’s view, the bourgeois interior of the late nineteenth century was the emblem of individuality, a sheltered place in which bourgeois man experienced himself as a creative and autonomous subject, striving for self-fulfillment and aesthetic enjoyment through the objects arranged in his dwelling. The social and economic upheaval after World War I, along with new mass media, enabled different forms of cultural production and aesthetic innovation that could be confined neither to the interior nor to any aims of individual self-expression. Cultural forms proper to the twentieth century ushered in a “liquidation of the interior” Benjamin claimed.

20 The function of art was no longer to create individuals but to affirm collective modes of life. The topos of the interior as a space of individuation was replaced by the topos of the street as a space of collectivity. An entry in Benjamin’s

Arcades Project describes the transformation:

Streets are the dwelling place of the collective. The collective is an eternally unquiet, eternally agitated being that—in the space between the building fronts—experiences, learns, understands, and invents as much as individuals do within the privacy of their own four walls. For this collective, glossy enameled shop signs are a wall decoration as good as, if not better than, an oil painting in the drawing room of a bourgeois; walls with their “Post No Bills” are its writing desk, newspaper stands its libraries, mailboxes its bronze busts, benches its bedroom furniture, and the café terrace is the balcony from which it looks down on its household…. More than anywhere else, the street reveals itself in the arcade as the furnished and familiar interior of the masses.

21The public spaces of the city serve as

interieur for the masses, and the exterior walls are their writing desks. The same idea motivated Marianne Brandt’s and László Moholy-Nagy’s theory of the photoplastic image, launched as a visual language addressed to urban crowds who would find enjoyment in this new public art while at the same time digesting the messages posted onto walls and façades. Benjamin, Brandt, Moholy-Nagy, and a number of other intellectuals of the interwar period sought to define spaces for cultural and political representation through which the masses could appropriate the productive forces that so far had served to control them. How to turn these instruments of oppression into means of liberation? In answering this question, they attributed great importance to two phenomena: first, the architecture and technology that made up the material infrastructure of the modern life world; second, new media technologies such as photography, film, radio broadcasting, the newspaper, and the illustrated magazine, which circulated in these new channels. These phenomena were considered as constitutive of urban modernity, reflecting the rapid development of the productive forces of capitalism and, at the same time, generating new modes of private and public life, along with corresponding forms of sociation, both individual and collective.

Whereas most thinkers of the Weimar era argued that the masses heralded the destruction of culture, the intellectuals highlighted in this final chapter argued that the masses prefigured progressive forms of art and cultural production. Sometimes, the masses were even seen as the covenant for a more advanced community that would turn human labor and technology into means for achieving truly human ends. Primary among these new forms of cultural production were the new visual media. Reviewing a photography book by Karl Blossfeldt, Walter Benjamin argued that photography provides the language of the future: it allows people to look deeper into the material realm and to uncover its underlying patterns, thus “altering our image of the world in as yet unforeseen ways” Benjamin also quoted Moholy-Nagy, whom he called “the pioneer of the new light-image”: “The limits of photography cannot be determined. Everything is so new here that even the search leads to creative results. Technology is, of course, the path-breaker here. It is not the person ignorant of writing but the one ignorant of photography who will be the illiterate of the future.”

22Benjamin argued that the camera provides for collective vision as its lens detects images and forms indecipherable to a pair of individual eyes: “unfathomable forms of the creative, on the variant that was always, above all others, the form of genius, of the great collective, and of nature”

23 Seeing beneath appearance, seeing differently, seeing deeper, the camera takes stock of organizational designs stored in the oldest sediments of the human collective. In a later essay, Benjamin would describe it as the “optical unconscious.” Making these designs conscious amounted to a renewal of the political imagination. Camera pictures could therefore serve political emancipation.

Of course, they might just as well serve purposes of objectification, oppression, and manipulation. Cases in point are what Siegfried Kracauer described as the mass ornament and what Theodor Geiger called the optical mass, in which the lens is so far removed from social reality that people inevitably appear as compact and anonymous masses. Most images, ideas, and theories of the masses in interwar Europe employed this strategy, either literally or figuratively, thereby making human beings comparable to ants. “And what can we say about an ant-heap?” Alfred Döblin asked in 1929, characterizing the remote viewpoint of historians, sociologists, and economists. “There may be some five hundred ants moving across a path, coming from a root, or from a pile of stones, in a fast and conspicuous movement. A hundred yards away there is an even larger crowd of them at work.” As with ants, so also with humans, Döblin concluded: “Viewed from a certain distance, distinctions vanish; from a certain distance, the individual ceases to be”

24The major question emerging from this context was whether the masses were best comprehended from afar or from nearby, from the outside or from the inside. What if the photographer’s camera, the sociologist’s gaze, or the writer’s vision ceased to distance itself from the crowd and instead planted itself in its midst? No longer seen as colored dots against the pavement or as a black wall on the horizon, the social body would then appear as faces and bodies in motion surrounding the sociological gaze or seeping through it, just as the subject in Robert Musil’s novel was transformed into a rock washed over by a stream. Walter Benjamin’s theory of modernity hinges on a reversal of this kind, which in his view amounted to no less than a cultural revolution. No longer separated from society, no longer surveying the masses from above or from afar, the aesthetic work would “be absorbed by the masses,” as Benjamin put it in his essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility”

25 Once the aesthetic work, or the medium of representation, disappeared into the crowd, the image of the mass was inverted and turned into a collective imagination in its own right. Benjamin speculated about a dialectical reversal of the subject and object of representation. Where there was once an unknown “Delta formation” an object of fear hovering at society’s outermost border, there would now be a self-conscious subject of history occupying the central square. Where there was once an objectifying representation of the mass as inert human matter, there would now be a self-performing collective.

The crowd was the subject most worthy of attention for nineteenth-century writers, Walter Benjamin asserted in his last essay on Charles Baudelaire. Through the spread of literacy, the masses were taking shape as a reading public. They became customers of culture and wanted to be portrayed in the novel. Victor Hugo, according to Benjamin the most successful writer of the century, went so far as to acknowledge the demands of the masses in the very titles of his novels:

Les misérables, Les travailleurs de la mer. Even in an esoteric poet like Baudelaire, Benjamin detected urban crowds swarming inside the sonnet stanzas and prose poems: “In

Tableaux parisiens the secret presence of a crowd is demonstrable almost everywhere”

26Judging from Benjamin’s essays of the 1930s, the crowd was an even more adequate topic for the early-twentieth-century intellectual and one that, with the emergence of fascism, was of utmost political importance. When Benjamin corresponded with Theodor W. Adorno about his work on Baudelaire, Adorno described “the notion of the mass as a secret code,” the deciphering of which would afford fundamental insights into the historical relation of art and politics.

27Benjamin’s

Arcades Project is usually seen as an investigation of the emergence of modernity and the cultural forms corresponding to it. Central to this project is Karl Marx’s notion of commodity fetishism, which Benjamin extracted from Marx’s analysis of capitalism and redefined as the determining factor of the culture of modernity.

28 Benjamin approached nineteenth-century France by studying the nodes and hubs in the system of circulation and consumption of commodities: shopping arcades, boulevards, railway stations, factories, world exhibitions, and department stores, among others. In these locations Benjamin detected the formation of a new kind of collective: aggregations of men and women acting as vendors or buyers of things and services and thereby instituting a social life organized by the elementary yet mysterious reality of exchange value. When referring to this new collective, Benjamin spoke of the masses.

Benjamin did not summarize his theory of the mass in a single essay or book, although there is much to suggest that the

Arcades Project would have contained a comprehensive treatment of the masses had it been completed. In order to reconstruct Benjamin’s notion of the mass we must therefore stitch together his main essays and drafts of the mid- to late 1930s: “The Paris of the Second Empire in Baudelaire” (1938), “On Some Motifs in Baudelaire” (1940), “Central Park” (1939), “The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility” (1936), “The Author as Producer” (1934), “On the Concept of History” (1940), as well as the

Arcades Project, which furnished a reservoir of ideas and motifs that was later tapped and refined in the essays.

Allusions to crowds, masses, and collective behavior and action abound in these writings, to such an extent that it is safe to say that this is one of their main concerns. Miriam Hansen goes as far as stating that Benjamin, in “The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility” posited the masses as “

the problem of modern politics.”

29 However, the immense literature on Walter Benjamin does not contain any consistent attempt to reconstruct his theory of the masses. The notion of the masses is also virtually absent from the standard reference books on his work.

30 Hansen’s work is an exception, yet she, too, fails to seize the content and intention of Benjamin’s notion of the masses as she concludes that it “ultimately remains a philosophical, if not aesthetic, abstraction.”

31 As I will demonstrate, it is more plausible to see in Benjamin’s analysis of the masses his discovery of the concrete mediation between culture and economy in nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century capitalist society. He traced the transformation of this mediation up until the 1930s, at which point he would identify the masses as the key political problem that had to be resolved in order to create a democratic, which for Benjamin translated into communist, society.

One reason that no one has bothered with this exegesis is that it is hard to decipher what Benjamin actually means by terms such as mass (

Masse), crowd (

Menge), collective (

Kollektive), people (

Volk), class (

Klasse), proletariat, petty bourgeoisie, and bourgeoisie.

32 This conceptual obscurity derives mainly from the fact that Benjamin uses these terms in three different ways: either colloquially, as in everyday speech, or as theoretical concepts or, again, as dialectical images elucidating the social function of art and culture. This being said, there is no doubt that the terms form a coherent conceptual structure. A sentence in “Central Park” proves Benjamin’s awareness of the terminological choices involved: “On the concept of the

multitude and the relationship between ‘crowd’ and ‘mass’ [Über den Begriff der Multitude und das (Verhältnis) von ‘Menge’ und ‘Masse’]”

33 As we shall see, Benjamin’s theory of modernity hinges on careful distinctions between “crowd” “mass” “proletariat” “petty bourgeoisie” and “people.”

Once we look closer at Benjamin’s analysis of these categories we notice that his first impulse is often to treat the mass as a simple matter of fact. His twin essays on Baudelaire and Paris immediately establish the crowd as the most conspicuous feature of urban modernity and take it as a point of departure for a diagnosis of the arts, literature, and culture of modernity. What do we mean by “the masses” that put their stamp on Baudelaire’s lyric poetry, Benjamin asks? These masses, he contends, “do not stand for classes or any sort of collective; rather, they are nothing but the amorphous crowd of passers-by, the people in the street.”

34Benjamin here uses “the mass” as a descriptive term designating the urban crowd as it appeared to nineteenth-century metropolitan writers, and for this purpose he usually employs the word “

Menge.” The amorphous city crowd was a new and overwhelming phenomenon, a creation of mid-nineteenth-century industrial society, which caused concern among writers and painters who would seek to render this new aspect of their city in words and images. Benjamin’s main examples are Edgar Allen Poe’s short story “The Man of the Crowd” and Friedrich Engels’s report

The Condition of the Working Class in England, but he mentions a whole range of other books, artworks, and genres that took the crowd as their primary object. Charles Mercier’s city panoramas, Balzac’s catalogs of urban physiognomies, and Daumier’s and Grandville’s caricatures are all to be seen as different attempts to describe and decipher the urban masses. According to Benjamin, they introduced new metaphors and topics as the expanding city was compared now to wild forests, now to terra incognita, while the crowds inhabiting it were portrayed as internal savages and barbarians. The crowd was described as a milieu in which all sorts of promiscuous and criminal behavior were not just concealed but also actively cultivated. Crowds became objects of fear and suspicion, sheltering crime, conspiracy, and depravity. The detective story was a product of this environment. It invented a new kind of hero endowed with the eyes and ears needed to track down criminals and

conspirateurs who used the dense and changeable crowd as a protective veil or hiding place. Dwelling on the origins of the detective story, Benjamin shows how the crowd offered a space that allowed a person to disguise his identity but also to protect it or to liberate himself from it. As Benjamin then moves on to discuss Baudelaire’s poetry, he shows that although Baudelaire rarely depicts the crowd

en face, it remains the medium and external force that give meaning to the poet’s characteristic oscillation between self-celebration and self-effacement.

Walter Benjamin thrives as a cultural historian mining the archives for items related to Paris’s crowds. Why does he devote so much attention to the masses? According to him, the masses were closely linked to the emergence of an economy centered on the mass production of commodities. Here’s an example from the notes covering “Arcades, Magasins de Nouveautés, Sales Clerks”: “For the first time in history, with the establishment of department stores, consumers begin to consider themselves a mass. (Earlier it was only scarcity which taught them that.)”

35 Another instance is found in his file on “Saint-Simon, railroads”: “The historical signature of the railroad may be found in the fact that it represents the first means of transport—and, until the big ocean liners, no doubt also the last—to form masses”

36In these remarks the mass is no longer a colloquial description of “people in the street” but a theoretical category designating a new collective that corresponds to a particular economic and technological domain. If the city of modernity invented urban and architectural technologies geared to optimize manufacture, transportation, and marketing of commodities, and if this architecture amounted to a new environment for the urban population, it also created forms of sociation and individuation adequate to the new milieu: “The most characteristic building projects of the nineteenth century—railroad stations, exhibition halls, departments stores …—all have matters of collective importance as their object…. In these constructions, the appearance of the great masses on the stage of history was already foreseen”

37A stage prepared for the arrival of the masses: such is Benjamin’s congenial description of the modern city and its commercial infrastructure. This also explains why he argues that the mass is a secondary phenomenon, a symptom of historical change rather than its cause:

Its secondary [social] significance depends on the ensemble of relations through which it is constituted at any one time and place. A theater audience, an army, the population of a city comprise masses which in themselves belong to no particular class. The free market multiplies these masses, rapidly and on a colossal scale, insofar as each commodity now gathers around it the mass of its potential buyers.

38As a theoretical concept, then, the mass is the social expression of the capitalist logic, which constitutes the essence of the urban crowds gathering in arcades, galleries, and department stores designed for the new cult of the commodity. In addition, and precisely by virtue of being the dominant social form of cultural modernity, the mass constitutes the visible social context of human experience and artistic and literary production in nineteenth-century France. In other words, the mass is a category of mediation: it allows Benjamin to link his economic analysis of the commodity form to his analysis of Baudelaire’s poetry, Hugo’s novels, or other great crowd scenes found in nineteenth-century culture, and also to a vast number of nineteenth-century social types (collector, flâneur, bohemian, prostitute, gambler, idler), architectural inventions (arcade, boulevard, winter garden, railway station), political movements (Fourier, Saint-Simon, the June insurrection of 1848, the commune of 1871), visual technologies (photography, panorama), cultural institutions, notions, styles, objects, and genres (museum,

interieur, mirror, automaton), all of which are indexed in the convolutes of the uncompleted

Arcades Project. Most if not all of these phenomena derive their ultimate importance as either producers of masses or as reaction-formations vis-à-vis the masses.

Benjamin’s conception of the mass thus differs from most others we have encountered so far, except, possibly, from those of Bertolt Brecht and Siegfried Kracauer. He does not approach the mass deductively, as did sociologists and cultural philosophers of Weimar Germany, who defined the mass by negation as a social aggregate lacking organization, individuality, and rationality, and hence as an agent of disorder. He also does not approach the mass as a psychological category, as did Freud and the mass psychologists preceding him, who defined the mass as a temporary or permanent gathering of people whose psychic identifications and passions are turned toward the same external stimulus. Benjamin also branches off from most post-individualistic accounts of the mass, according to which the mass was made up by people lacking means to represent themselves coherently as individuals with firm identities and positions. Deviating from these theories, Benjamin defined the mass by identifying its material condition of possibility, which he located at the economic level, in a system of production that put out saleable goods in great quantities and in a system of marketing that attracted customers in large numbers. In “Central Park,” he stated the matter straightforwardly: “The masses came into being at the same time as mass production.”

39However, the definition of the mass as a social effect caused by the city’s accelerating circulation of commodities is only the first element in Benjamin’s theory of modernity. For the metropolis does not only form masses as a by-product of an economy centered on commodity production. It also supplies these masses with compensatory environments, allowing them to escape the commodification of their existence and to fantasize about themselves as authentic individuals and independent agents of civilization: “As soon as the production process began to draw large masses of people into the field, those who ‘had the time’ came to feel a need to distinguish themselves en masse from laborers. It was to this need that the entertainment industry answered”

40We may extrapolate Benjamin’s argument: the masses are not just consumers of mass-produced and mass-marketed goods but also a collective whose members fulfill their dreams of social harmony and existential wholeness through the historically new activity of consuming mass-produced stories and images. In this sense, the mass is what Benjamin called a “dreaming collective,” which attributes powers of magic and healing to the commodity. This mass lives and moves in an urban environment constructed so as to prolong this dreaming: “All collective architecture of the nineteenth century constitutes the house of the dreaming collective,” Benjamin writes.

41 He draws up a list of some of these “dream houses of the collective: arcades, winter gardens, panoramas, factories, wax museums, casinos, railroad stations.”

42 Had Benjamin written about the 1920s and 1930s, he would have added the movie theater to his list. In such spaces, the newly emergent urban crowds contemplate images of themselves as masters of nature and history. Benjamin’s notion of the mass thus has at least two sides. On the one hand, the mass is a social formation instituted by the capitalist commodity economy and shaped by the architectural and commercial infrastructure corresponding to that economy. On the other hand, the mass is a vehicle for a new culture—patterns of social interaction that ignite sensations, fantasies, and dreams, thus becoming a source of what Benjamin calls collective phantasmagorias: dream images of the past, present, and future that are constantly rekindled by the circulation and display of commodities. In both senses, Benjamin’s masses show strong traits of what he and other Marxists called the petty bourgeoisie.

It is easy to see why the mass served Benjamin so well as a dialectical image. At one stroke, his notion of the mass reveals two faces of the historical process: the relation of commodity and culture or of economy and experience. To put it simply, the mass is a social phenomenon that reveals how base and superstructure are connected in high-capitalist modernity.

However, it is not as simple as that. By examining how the relation of economy and experience was expressed in the masses, Benjamin was also able to account for the emergence of a social idea that remained dominant in his own era: “the individual,” which he regarded as the supreme phantasmagoria of the nineteenth century.

Benjamin explained that the individual was an effect of the mass by analyzing two phenomena typical of early urban culture, the flâneur and the interieur. Both emerge as figurations of the nineteenth-century conviction that the individual is the basic unit of reality. In Benjamin’s analysis, however, both the interieur and the flâneur are products of the mass, in the sense that the urban crowds constitute the raison d’être of both. The bourgeois interior, for its part, is in Benjamin’s view a sheltered space where the individual seeks refuge from a society that is becoming increasingly compartmentalized into specialized professions and activities. It is a compensatory realm, where “man” estranged from the world of commodities that he has produced and that now begin to produce him, can preserve an “authentic” relationship to the world and continue to believe in his own unique individuality.

As for the flâneur, we saw already in the previous chapter how for Siegfried Kracauer the flâneur was equal to a new mode of apprehending society that could be approximated to the very subjectivity of the masses. The main theorist and historian of the flâneur, Benjamin explores the history and political potential of this new collective subjectivity. He starts by showing that the flâneur is the very opposite of the bourgeois subject cultivating his individuality in the interior. For the flâneur it is the street itself that that serves as a living room. The flâneur’s arrival on the historical stage is anticipated by a number of other historical figures, all of them moving at the margins of urban life and ranging from the

conspirateurs of early revolutionary sects, to radical students and all kinds of bohemians, all the way to the artists and writers who are forced to make a living on the marketplace. People without strong class affiliations and as yet without strong ties to the bourgeoisie, the flâneurs are free-floating intellectuals: eyes, ears, pens, and painters of public life, of streets, taverns, and cafés. In short, they are those who wrest a living by recording their impressions of public life in the growing public mass media such as the newspaper feuilleton and the serialized novel.

The city’s dense concentrations of people constitute the medium through which the flâneur perceives reality, writes Benjamin. For the flâneur, the masses fulfill several functions: “They stretch before the flâneur as a veil: they are the newest drug for the solitary.—Second, they efface all traces of the individual: they are the newest asylum for the reprobate and the proscript.—Finally, within the labyrinth of the city, the masses are the newest and most inscrutable labyrinth.”

43 What characterize the flâneur’s perception are sensations of movement, density, quantity, anonymity, collisions, and adventure, and these sensations are all generated by the crowd. Like Kracauer, Benjamin argues that the flâneur represents a historically new way of apprehending reality, one that is marked by quick sensations rather than enduring experiences and by a vulnerability of self that forces him to continuously reinvent his identity and redefine his position vis-à-vis others. Richly orchestrated by writers and artists of the period, the flâneur’s experience of crowds is marked by a tension between the observer’s wish to master the masses with his gaze and mind, thus providing a heightened sense of self, and his simultaneous temptation to lose himself in the collective. The flâneur turns this tension into his

modus vivendi.As I already stated, however, the presence of the masses was not always explicit in the art and literature of the nineteenth century. Writers and artists were far more preoccupied by the individual, narrating or depicting his path of personal cultivation, the education of his feelings, or the disillusion he suffered as he ran up against the powers of the establishment. Still, the individual’s attitudes and actions were nonetheless conditioned by the subject’s proximity to the urban crowds, Benjamin argued. In a crucial passage he asserts that the increasing valorization of individuality was the result of the increasing dominance of the masses. “Individuality, as such, takes on heroic outlines as the masses step more decisively into the picture.”

44Therefore, the paradigmatic emotions of modernist art, solitude and ennui, which are experienced by virtually all literary heroes of the period, from the protagonists of Gustave Flaubert (

L’éducation sentimentale) to those of Knut Hamsun (

Sult), only make sense once we picture these heroes uneasily rubbing themselves against city crowds. Baudelaire is Benjamin’s primary example: “The mass has become so much an internal part of Baudelaire that one seeks in vain for any descriptions of it in his work.”

45 A page or so further down, Benjamin remarks about Baudelaire’s sonnet “À une passante” that “the crowd is nowhere named in either word or phrase. Yet all the action hinges on it, just as the progress of a sail-boat depends on the wind”

46 This was Benjamin’s discovery: the mass, nowhere named or described, yet omnipresent, to the extent that it could be posited as the first obsession and primary content of the culture of modernity. Or, to put it differently, this was Benjamin’s discovery of the critical relation of nineteenth-century experience to its exterior. Crucially, it was a dialectical relation, insofar as what appeared to be a relation to an external phenomenon—the crowd—was also an internal tension within the individual subject and the work of art itself.

Benjamin uses Baudelaire’s sonnet “À une passante” as an object lesson on the dialectics between individual and mass (which Baudelaire, remaining firmly inside the patriarchal order of his era, depicts as an encounter between male gaze and female body). The poem relates how the flâneur sees a woman coming toward him, their eyes meeting for a moment, after which she again disappears. Baudelaire mentions that the woman is dressed in mourning, “en grand deuil” and Benjamin seizes on this detail. The veiled woman appears like a revelation, her figure emerging from the crowd in the same way as a face comes unveiled. Benjamin uses the image of the veil innumerable times. Things and objects are unexpectedly “unveiled” as they detach themselves from their embeddings to excite the senses of the flâneur. The veil is a source of fascination, and so is the secret it hides. “The masses [

die Masse] were an agitated veil, and Baudelaire viewed Paris through this veil,” Benjamin explains.

47 In a different context, he states that “the crowd [

die Menge] is the veil through which the familiar city is transformed for the flâneur into a phantasmagoria”

48 In yet a different entry, already quoted above, he remarks that the masses (

die Masse) “stretch before the flâneur as a veil.”

49In the above quotations, crowd and mass (

Menge and

Masse) are obviously synonymous; both refer to the impression of people moving in the street, the anonymous and unknown inhabitants of the metropolis. However, a fourth entry increases the complexity of the image: “For the flâneur, the ‘crowd’ is a veil hiding ‘the masses’ [Die ‘Menge’ ist ein Schleier, der dem flaneur die ‘Masse’ verbirgt]”

50 Whereas the mass previously was likened to a veil, it is now, strangely enough, described as reality hidden by the veil of the crowd. How to understand this sudden shift of meaning? What remains constant, throughout these entries, at least, is the image of

the crowd (

Menge) as a veil. To see the city and its inhabitants as through a veil obviously implies that reality is partly concealed: the city crowd appears as a phantasmagoria filled with secrets. But the veil does not just entice and agitate. It also puts a filter on reality and prevents something from coming into view. “The ‘crowd’ is a veil hiding the ‘masses.’” Remove the veil, remove the spectacle of the urban crowds, remove its fascinating heterogeneity and variegation, its endless stream of shimmering appearances, and what comes into view is “the mass” (

Masse) in the more theoretical sense of the term: a world ruled by a quantitative and repetitive accumulation of exchange value, that is, by a capitalist logic piling humans and things onto one another as commodities while turning the people that are exposed to this logic into a new class of petty bourgeois retailers, shopkeepers, and consumers whose life, work, and thinking are objectively delimited by their position vis-à-vis the production, marketing, and consumption of commodities.

In this more theoretical sense, Benjamin clearly states that the individual flâneur is himself an embodiment of the logic of the commodity that turns all things and all humans into replaceable units in a mass. The flâneur, he explains, is someone abandoned in the crowd. This places him in the same situation as the commodity, for it, too, appears on the store shelf without trace of its origins or of the hands that produced it. “The intoxication to which the flâneur surrenders is the intoxication of the commodity immersed in a surging stream of customers.”

51Individual and commodity here turns out to be made of one piece; both are creations of the implacable laws of the market. Separate, unique, independent, sovereign—these qualities attributed to the hero of modernity, the individual, are also characteristics of the commodity as it is perceived as a fetish with a soul of its own.

52 The individual feels himself or herself as the very opposite of the mass—and most nineteenth-century culture helped tailor that feeling into a firm conviction. As Benjamin argues, however, individualism and massification are governed by the same historical logic through which the human being is atomized, turned into the isolated monad celebrated by individualism and then joined to other such human units into the great aggregate of the mass. Massification, individualization, commodification: all are facets of one single process.

If the mass functions as a secret code in nineteenth-century culture, and if it was Benjamin’s great discovery to establish the presence of that code inside virtually every piece of art, literature, architecture, and popular culture created in that period, it remains to be seen what this code ultimately meant. As a dialectical image, the mass expressed an undividable constellation of economic life and mental life, of commodity production and collective dreaming. The mass revealed that the commodity is the soul of the culture of modernity, in which social life and historical progress are identical to the process by which everything and everyone are transformed into commodities and subjected to the logic of capital. The mass, in Benjamin’s analysis, represents the reduction of history, society, nature, and life itself to an eternal sameness produced on the conveyor belt.

As a cultural phenomenon, then, the mass is a collective of petty-bourgeois character organized around the cult of the commodity. The social relations within the mass are constituted by the participants’ position in the circulation of exchange values. As commodity circulation assumes fetishistic qualities, however, it is perceived as a source of historical, cultural, and aesthetic values, through which the members of the collective construe a sense of authenticity and individuality. Such is the phantasmagoric quality of the mass, preventing the members of the collective from apprehending the impersonal, economic powers governing their world while at the same time convincing them that they are themselves independent individuals living and acting in accord with their own free will.

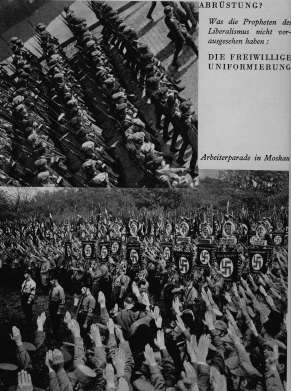

Benjamin saw the similarity between the sleeping collective of the nineteenth century and the fascist communities of the 1930s. In both cases, the collective was held in spell by alluring utopias, which prevented it from perceiving its actual enslavement. The mass was thus not just the secret code with which Benjamin unlocked the relation of nineteenth-century culture to the realities of industrial capitalism. In addition, it was a code that offered an understanding of Benjamin’s present, which had fallen under the rule of fascism’s successful mobilization of the masses and their subsequent transformation into a nationalistic people’s community, or Volksgemeinschaft. This is the moment to look at the continuation of a passage that I quoted above:

The free market multiplies these masses, rapidly and on a colossal scale, insofar as each commodity now gathers around it the mass of its potential buyers. The totalitarian states have taken this mass as their model. The

Volksgemeinschaft aims to root out from single individuals everything that stands in the way of their wholesale fusion into a mass of consumers. The one implacable adversary still confronting the state, which in this ravenous action becomes the agent of monopoly capital, is the revolutionary proletariat. This latter dispels the illusion of the mass with the reality of class.

53The appearance of the mass yields to the reality of class. Yet in order for this to occur, the proletariat must “dispel the illusion” that prevents people from seeing the true origin of the commodity without distortions. The phantasmagorias emitted by the commercial and cultural institutions of bourgeois society would then dissolve. The inhabitants of the metropolis would realize that their position in society is not primarily determined by their role as consumers but by their position in a system of production that divides humanity between those who are forced to become commodities, selling their labor, and those who can buy that labor and extract a surplus from it. According to Walter Benjamin, this is the “undistorted reality” that, once the veil is torn, underlies the exhilarating panorama of the urban crowd.

I suggested that Benjamin’s theory of modernity could be glimpsed in his distinctions among crowd, mass, proletariat, petty bourgeois, and people (

Menge, Masse, Proletariat, Kleinbürgertum, Volk). As we have seen, Benjamin evokes the crowd as an object of visual pleasure and existential adventure, sometimes likened to a labyrinth, sometimes to a shimmering veil. Benjamin’s crowd (

Menge) is thus a phantasmagoric appearance behind which the critic detects the deeper reality of the mass (

Masse). The mass, in turn, is also a secondary phenomenon brought into being by the commodity economy as each commodity and each site of commodity exchange, such as the arcade or the department store, effectively

forms the mass that is appropriate to it. Deeper still, there awaits a third kind of collective formation, the class. It constitutes itself at the moment when the mass becomes conscious of its subordination to the rule of the commodity or revolts against that rule.

Yet the superstructure of culture and knowledge erected by the victorious bourgeoisie prevents the mass from becoming conscious of the rule of the commodity. This culture presents itself as a phantasmagoric universe promising satisfaction of all desires and fulfillment of all dreams. This is why the dreaming collective of the nineteenth century prefigures the fascist collective of the twentieth. Fascism completes the process of dehumanization and de-individuation at the heart of the commodity economy; at the same time it invents a social form, the racialized Volksgemeinschaft, in which the individual’s absolute subjection is a prerequisite for his or her existential fulfillment and social recognition. A long footnote to the second version of “The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility” in which Benjamin directly addresses “the ambiguous concept of the masses” seems to confirm this view. He speaks of fascism’s cunning use of the laws of mass psychology as it seeks to form “compact masses” infused by “the counterrevolutionary instincts of the petty bourgeoisie” In conjunction to this he sketches a history of the masses:

The mass as an impenetrable, compact entity, which Le Bon and others have made the subject of their “mass psychology” is that of the petty bourgeoisie. The petty bourgeoisie is not a class; it is in fact only a mass. And the greater the pressure acting on it between the two antagonistic classes of the bourgeoisie and the proletariat, the more compact it becomes. In

this mass the emotional element described in mass psychology is indeed a determining factor. But for that very reason this compact mass forms the antithesis of the proletarian cadre, which obeys a collective

ratio.

54As Benjamin judged the historical drama: whereas fascism obtained the ideal community according to the conventional prescriptions of mass-psychological doctrine, that is, through obedience and aesthetic glorification of the leader, socialism would achieve

its ideal community through human liberation and political self-representation of the collective, enabled by a leader whose “great achievement lies not in drawing the masses after him, but in constantly incorporating himself into the masses, in order to be, for them, always one among hundreds of thousands.”

55Benjamin’s analysis thus moves from the crowd (as the collective expression of cultural and visual phantasmagorias offered by urban life), to the mass (as the collective expression of the commodity economy, and often identified with the petty bourgeoisie), and onward to the proletariat (as the collective expression of capitalist exploitation and of revolutionary resistance), which “is preparing for a society in which neither the objective nor the subjective conditions for the formation of masses will exist any longer.”

56 These three analytical steps also mark the progression of the gradual awakening of the collective. Benjamin’s objective for the

Arcades Project was thus to extract from the dreaming collective of the masses, which he identified with the petty-bourgeois collective, the awake and self-conscious proletarian collective. “Wouldn’t it be possible,” he states in an early entry, “to show how the whole set of issues with which this project is concerned is illuminated in the process of the proletariat’s becoming conscious of itself?”

57Benjamin never investigated the concrete historical preconditions for the emergence of the proletariat as a revolutionary agent. It is clear, however, that he perceived such a scenario as the only alternative to fascist mass politics. As the Second World War continued, his belief in revolutionary change became increasingly militant—and, one should add, increasingly abstract and utopian. In his last piece of writing, the theses “On the Concept of History,” the revolution flares up as the universal solution and sole hope in times of darkness. The proletariat, we are told, is capable of “a tiger’s leap” into the future: this “leap in the open air of history is the dialectical leap Marx understood as revolution.” The proletariat figuring in Benjamin’s theses on history is the virtual equivalent of the Messiah. “What characterizes revolutionary classes at their moment of action is the awareness that they are about to make the continuum of history explode.”

58Adorno criticized Benjamin for giving the proletariat the role of deus ex machina in the historical drama.

59 His objection was to the point. Benjamin’s texts are not the place to look for sociological arguments concerning the actual motivations of the working classes to become the subject of history. Rather, the proletariat’s revolutionary calling was in his view an ontological idea. A self-proclaimed “constructivist” Benjamin believed that the truth of history is accessible only to those who actually construct the historical world with their own labor.

60 In his diary, he approvingly noted a conviction of Brecht’s: “The sense of reality of the proletarian is incorruptible.”

61 Thus, rather than examining the proletariat’s sense of reality, Benjamin took it as pregiven.

62But are there any workers at all in the arcades? asks Jacques Rancière in an article on Benjamin’s philosophy of history. He observes the striking disparity between Benjamin’s rich commentary on the arcade as the embodiment of petty-bourgeois modernity and the rare notes, most of them raw excerpts, that he devoted to laboring people of nineteenth-century Paris.

63 One entry in the

Arcades Project seems to admit as much. “It is a very specific experience that the proletariat has in the big city—one in many respects similar to that which the immigrant has there”

64 Apparently, the working classes do not belong in the crystal palace of bourgeois modernity. Still, Benjamin is convinced that they hold the key to progress. The social function of this class is thus the opposite to that of the masses. Masses were formed by the capitalist market and the circulation of exchange values. The proletariat was brought into being by capitalist

production. To step from the appearance of the mass to the reality of class was thus to step from the sphere of consumption to the sphere of production—in a way corresponding to Karl Marx’s analytical move in the first volume of

Capital, where the reader, having just been taught everything he should know about the circulation of money and value, is suddenly invited to enter “the secret workshop of production, above the gates of which is posted a board saying: No admittance except on business”

65Marx actually entered the capitalist sweatshop, carefully analyzing the power relations, business organizations, capital investments, factory work, and wage systems at the basis of European capitalism. Benjamin’s step toward the sources of production ends up elsewhere, in a materialist cosmogony, or a myth of creation. The secret of production may be beheld not by describing the relation between worker and owner in the capitalist system but by studying the timeless relation between the human organism and nature, especially the skill and vision with which somebody transforms matter. In other words, Benjamin’s model of production is based on an idea of nonalienated labor, where working ideally involves play, creativity, self-expression, existential fulfillment, and community building. In utopia, work would be conducted on the model of children’s play, Benjamin states: “All places are worked by human hands, made useful and beautiful thereby; all, however, stand, like a roadside inn, open to all.”

66Benjamin always paid particular attention to the world makers—peasants, artisans, children, and workers—who know how to make the world inhabitable by transforming matter with hands and minds. His recurring references to the world of artisan labor and craftsmanship and his keen interest in toys and children’s theater are all part of his notion of authentic production as the foundation of human experience and its various cultural expressions.

67 To make the world is thus to know the world, and in capitalist modernity the proletariat is the class that makes the world.

For the system of capitalist production does not bring into being only “masses” of people ready to buy and consume what the factories deliver, and not just the immaterial know-how and technology needed for the production of these commodities. Crucially, capitalism also brings into being a social class whose sensory apparatus is profoundly shaped by these new technological forces of production. And this is why Benjamin can claim that the worker’s hands are somehow better adapted to handling the world of modernity, just as the eyes and ears of the working classes are superior to the dulled senses of the bourgeoisie when it comes to understanding modern society.

For instance, the worker’s eye is thus on a par with the technical eye of the camera, Benjamin argues. Both see beneath appearance, both see differently, and both see deeper. There is also a parallel between the proletariat and cinema because film is produced, edited, and narrated according to a cutting technique similar to what obtains in factory work. Moreover, both cinema and factory work rely on a rational division of labor. In the production of an automobile or a film, no single individual is skilled enough to run the production process as a whole, in the way an individual craftsman controlled the manufacturing of an object. Rather, the manufacture of commodities as well as the creation of artworks takes on a collective character, which makes the idea of the autonomous individual and the artistic genius obsolete. However, manual work and spiritual work do not just become collective. They are also increasingly determined by a common logic or a common mode of production characterized by a strong reliance on machinery and technological devices. Benjamin’s designated this logic as one of “technical reproducibility,” arguing that it radically changes the function of art, the nature of political representation, and the properties of knowledge.

Benjamin stressed that large-scale dissemination of images enabled by camera and reproduction techniques had for the first time in history given common people access to reproductions of artworks as well as images of distant places and unknown parts of nature. Moreover, new techniques of reproduction had given these people a possibility to represent themselves for what they were—as the true producers of history. The collective itself, or even

work itself, was thereby given a voice.

68 Having previously been forced to rely on a class of sages who protected their own privileges of seeing and describing, people had now attained the means to present and represent themselves by using the camera. The transformation was already under way in Soviet Russia, Benjamin wrote: “Some of the actors taking part in Russian films are not actors in our sense but people who portray

themselves—and primarily in their own work process. In Western Europe today, the capitalist exploitation of film obstructs the human being’s legitimate claim to being reproduced.”

69Benjamin concluded that technology would be rationally employed at its highest potential only if placed under the control of the masses. Of course, this is standard Marxism: the full realization of society’s productive forces requires the abolishment of private ownership. Benjamin’s contribution to the Marxist doctrine was to develop a corresponding analysis concerning the forces of cultural production. Just as machine technology served as a way of exploiting factory workers, so was media technology used to subject the masses by disseminating phantasmagoric messages and images naturalizing their subordination. Fascism raised this use of media technology to a new level.

Technical development had brought the masses into being and turned them into consumers of the phantasmagorias made available by mass media. But the same technical development also offered the masses an opportunity to place themselves at the center of the historical stage and to present themselves as the conscious subjects of history. This is a decisive step in Benjamin’s analysis of the collective. As many commentators have pointed out, it is also a questionable, if not doubtful, move—the utopian tiger’s leap into the future.

70 By using new media technology to represent themselves and to fabricate themselves in their own image, people would put an end to their own existence as masses at the margins of the polity, transforming themselves into the constituent subject of society. The very principle of “technical reproducibility” that instituted the masses—as consumers and obedient political subjects—would thus “dispel the illusion of the masses with the reality of class.”

This self-transformation of the masses into a historical subject would also entail a profound change of the function of the artist and the writer. Adapting to new modes of cultural and aesthetic production that were collective in nature, they would relinquish their status as individual or autonomous creators placed at a distance from society. Instead, they would engage in collective production, as facilitators and experts in the effort to bring all parts of a variegated and heterogeneous society into representation and expression, a task entailing no less than the awakening of the collective.

Ultimately, it is this whole process of social and cultural transformation that Benjamin encapsulates in the first sentence of the final section of his artwork essay: “The Masses are a matrix from which all customary behavior toward works of art is today emerging newborn.”

71 Art is no longer placed above the masses as an object cherished for its cult value. Instead, it is valorized for what Benjamin calls its “exhibition value” No longer founded on ritual, the social function of art becomes based in politics: the artwork serves to

display the social community. Benjamin contrasts the old relation to art to the new one by comparing the attitude of the connoisseur of master painting with that of the distracted film spectator: “A person who concentrates before a work of art is absorbed by it [

versenkt sich darin]; he enters into the work, just as, according to legend, a Chinese painter entered his completed painting while beholding it. By contrast, the distracted masses absorb the work of art into themselves [

die zerstreute Masse dagagen versenkt das Kunstwerk in sich]”

72But—how can the masses “absorb” the work of art? Benjamin put great faith in the combined effect of new technologies of reproduction and representation, new forms of collective self-organization, and new forms of communal or communist ownership. The result would be what Bertolt Brecht called an

Umfunktionierung or functional transformation of all art forms in accordance with emerging socialist forms of production.

73 In his writings from the late 1930s, Benjamin always contrasted this ideal, to his great disappointment already partly betrayed in the Soviet Union, with that in fascist Europe. For fascism, too, allowed the masses a space within the field of representation, but only for the purpose of consolidating the hierarchy between rulers and ruled. The only way to avoid this development was to transfer the new means for cinematic and photographic production into the hands of the masses. If in traditional bourgeois culture the beholder was absorbed by the work of art, and if in fascist culture the masses were absorbed by a society turned into an artwork painted by the leader, then in Benjamin’s ideal communist society a third possibility was realized, in which the work of art was absorbed by social life itself.