Around the time Christopher Columbus sailed to the Americas in 1492, the number of smallpox cases spiked in Europe, Africa, and Asia. A killer from ancient times, the smallpox virus turned even more deadly. Three out of every ten people who caught it died—eight out of every ten children. In cities, smallpox returned so regularly—at least every twenty years—that the majority of adults were immune to the disease because they had survived a bout of it. Smallpox began to target young people who’d never been exposed and had no immunity. It became a dreaded childhood disease.

In the 1500s, no one understood what caused smallpox, how it was transmitted, that it was infectious before the rash appeared, that surviving one time meant lifelong immunity, how to treat it, or how to prevent it. Doctors did understand, however, that smallpox was a distinct contagious disease—one commonly called the pox.

If you caught smallpox, you’d suddenly feel out of sorts twelve days after exposure. Your early symptoms would include flu-like fever, faintness, headache, backache, nausea, and weakness. After a day or two, you’d feel a little better. But then your fever would spike again, you’d get a splitting headache as well as a knife-stabbing pain in your back. By day four, minute red spots would erupt in your nose, mouth, and throat. Then the rash would appear on your forehead and face—distinctive, red spots—and spread throughout your mouth, throat, down your upper back, chest, arms, and legs. The spots turned into brownish pustules—enlarged pimple-like bumps filled with milky fluid.

In bad cases of the pox, the pustules would spread over your eyeballs, your internal organs, and all your skin—including your scalp and the soles of your feet. The pustules in your mouth and throat would make drinking and eating difficult. With high fever and painful rash, patients often fell unconscious. Sometimes the pustules would grow inwards, hemorrhage, and bring early death. In horrific cases, the pustules would all run together and your rash-covered skin would separate from the underlying flesh, peeling off in sheets.

By day eleven, the pustules would flatten and then crust into scabs. Bacterial infection would often set in, adding a whole new set of complications. If you made it through the third week, when the scabs started to fall off, you survived. But your skin could be pockmarked with unsightly, white, indented scars, especially on your face. The scars would never disappear—you were marked for life—and you could be bald, blind, and infertile as well.

Does this sound like bad news? Not compared to what happened in the New World! Christopher Columbus brought the Old World to the New, including diseases. Within a few years, millions of Native Americans had died from smallpox. They got sicker faster—some died even before the pustules formed.

In 1518, Hernán Cortés, a Spanish soldier stationed in Cuba, persuaded the island governor, Diego Velázquez, to let him explore the coast of Mexico. This sounded straightforward enough—but Cortés had a secret agenda. He hungered for gold. A conquistador at heart, he would do anything, even commit murder, to fill his pockets. But Cortés never intended to unleash a pandemic that caused the deaths of millions of people.

Cortés outfitted a fleet of ships with soldiers and cannons. Just before he set sail, the Cuban governor began to suspect Cortés’s greed and cancelled his mission. Cortés sailed anyway. When he reached Mexico, he listened to the locals’ stories about the fabulously wealthy Aztec Empire.

Cortés and a small army of soldiers marched inland to the Aztec capital, Tenochtitlán. When they reached the city, Emperor Montezuma welcomed them. The Spaniards were amazed. Tenochtitlán was home to more people and a greater number of massive monumental structures than Seville, Spain. The gold glittering on the buildings and people bedazzled Cortés and his men.

In no time, Cortés took Montezuma hostage and demanded the empire’s gold as ransom. He also ordered that the Aztecs pledge allegiance to the Spanish king and accept the Christian god as their own. The Aztecs submitted, hoping to buy back Montezuma’s freedom.

In the middle of the coup, Cortés suddenly had to race back to the coast to surprise a Spanish Cuban force that was intent on arresting him. After he succeeded and returned to Tenochtitlán, Cortés found Montezuma dead—probably killed by his own people. The Aztecs chose a new emperor and rebelled against the Spanish. Cortés, his troops, and his entourage retreated. Many of his men drowned, sinking in lakes and rivers with their heavy armor. One of the Spanish soldiers or servants carried the smallpox virus—and that’s all it took to spread the disease to the Aztecs.

Two years later, Cortés returned to Tenochtitlán with a few hundred armed men. After a siege, he broke into the city and found half the population dead from smallpox. His chronicler Bernal Diaz wrote, “I solemnly swear that all the houses and stockades in the lake were full of heads and corpses … We could not walk without treading on the bodies and heads of dead Indians.”

The Aztec empire collapsed. As more Spaniards swarmed the New World searching for gold, they spread wave after wave of European diseases—smallpox, influenza, measles, scarlet fever, and bubonic plague. Pandemics raced ahead of the conquistadors—up the Mississippi Valley and down into South America.

Cortés and the Spanish believed that the death of so many was the will of God. In truth, the Native Americans died because they had no immunity to European diseases. These healthy peoples had lived in isolation from Europe and Asia for over ten thousand years. At the end of the last ice age, a land bridge between Siberia and Alaska flooded, cutting the Americas off from the Old World. Native Americans built their own civilizations, and—because they kept few domesticated animals—suffered few infectious diseases. Unlike Europeans, whose adult population carried a high resistance to smallpox, the Native Americans carried no resistance.

Thirteen years after the fall of Tenochtitlán, Spaniard Francisco Pizarro entered the Inca city of Cuzco in Peru. Smallpox was already killing the city’s population. Smallpox had burned like wildfire through the thousands of miles of land between Mexico and Peru, devastating countless communities all along the way. Pizarro toppled and looted the powerful Inca Empire with only a few hundred men.

In chains, the emperor sneered at Pizarro. “Did the Spanish eat gold?” he wanted to know. Pizarro said yes, they did. Pizarro got his gold not only because he was a clever, ruthless conquistador, but also because smallpox had decimated the Incas.

Over the next century when the English, French, Dutch, and Portuguese settled in the New World, they also spread disease. A few generations after the Puritans from England landed in Massachusetts and Connecticut, nine out of ten of the Narragansett and Mohawk peoples had died of smallpox, whooping cough, measles, influenza, or typhus. The Puritans thought they must be divinely favored because few of them died.

By 1645 in modern-day Ontario, the great Wendat nation was halved mostly by smallpox, but also scarlet fever, influenza, and measles—carried inland by Jesuit priests and fur traders. The story repeated itself over and over through the New World and then the South Pacific.

Smallpox flared up again with the sweeping movements of people during the American Revolution in 1776. After the war, smallpox reached the Pacific Coast, probably carried along native trading routes, decimating communities unknown to Europeans. When Captain George Vancouver of the British Royal Navy explored the Pacific Northwest in 1792, he found plentiful salmon and fresh water, but also deserted villages scattered with human bones—evidence of a recent catastrophe. Smallpox had left its scars.

North and South America may have been home to a hundred million people when Columbus, Cortés, and Pizarro appeared on their shores. Three centuries later, fewer than ten million remained.

Smallpox and Biological Warfare

Cortés may not have intended to spread smallpox in the Americas, but some Europeans did. In 1763, during the Seven Years War between the French and English to control the colonies, Sir Jeffrey Amherst asked his British troops to deliberately infect the Native American allies of the French. His officer in Pennsylvania agreed to smear blankets with the pus of active smallpox sores and distribute them among the native peoples. The ruse worked. Many Native Americans died, and eventually the English won.

Hindus in India discovered a way to control smallpox over two thousand years ago. Old manuscripts describe how Brahman priests traveled the countryside rubbing bits of dried smallpox scabs into the cuts or scratches of people who had never had the disease.

A thousand years later in China, people self-inoculated by inhaling a powder of ground-up scabs from recovering smallpox patients. Both methods transmitted small doses of the virus, but the resulting illness tended to be mild. If the inoculated were kept in isolation for a while, the disease did not spread. No one understood why this worked—just that it did. The practice slowly extended throughout Asia, Africa, and into Turkey.

In 1715, the beautiful Lady Mary Wortley Montagu of England, at the age of 26, caught smallpox. She survived, but her twenty-two-year-old brother did not. Beautiful no more, Lady Mary looked into her mirror to see a face pitted with scars and no eyelashes. She traveled with her husband to Turkey, where she discovered inoculation.

Lady Mary researched the process carefully and was so impressed that she had her young daughter, age four, inoculated. Over the next few years, she persuaded the Princess of Wales to inoculate her children. Lady Mary and promoters of the procedure called it variolation after the medical name for the disease (variola). They hoped to make inoculation popular.

About the same time in Boston, Massachusetts, Reverend Cotton Mather learned about inoculation from his African slave Onesimus. He persuaded a local physician to inoculate his patients, and together they were able to protect about 250 Bostonians during a smallpox outbreak in 1722.

Despite Lady Mary and Reverend Mather’s successes, inoculation did not catch on quickly. In both England and the American colonies, local authorities were cautious of the procedure—it made no theoretical sense, didn’t always work, and risked spread of the disease.

However, when smallpox reared its head partway through the American Revolution, George Washington, the first president of the United States, inoculated his Continental Army. He understood that the risk of a smallpox epidemic decimating his men was greater than the risks of inoculation.

In the late 1700s, farmers in Gloucestershire, England, noticed that dairymaids always had fair complexions. Most other women’s faces were pockmarked from smallpox. Although dairymaids were known to catch a milder disease, called cowpox, from the cows they milked, the scars from cowpox disappeared and the dairymaids never came down with smallpox afterward.

In 1774, a Dorset farmer named Benjamin Jesty decided to inoculate his wife and children with cowpox rather than smallpox. He hoped this would protect them from smallpox—like the dairymaids. Although his family was exposed to smallpox, they never developed the disease. Jesty told Edward Jenner, his country physician, and Jenner decided to test the observation.

Two years after Jesty’s experiment, Jenner took the fluid from a cowpox pustule on the wrist of a dairymaid and rubbed it onto the skin of a young boy named James Phipps. Then, even though Jenner tried again and again to give Phipps smallpox, the boy never caught it.

Jenner called this process vaccination, after the French word for cow: vache. The country doctor wrote up his research, but it was ignored by the medical establishment in London. Jenner continued experimenting and realized that a big selling point for vaccination was that it carried no risk for spreading smallpox.

English physicians were suspicious and slow to accept vaccination. It took another hundred years for scientists to figure out why inoculation and vaccination worked—and another half century after that to isolate the smallpox virus particle under an electron microscope. Jenner did, however, eventually receive honors and a cash prize for his discovery. And the hide of Blossom the cow, from whom he took material for his experiments, is still on display in a London hospital library.

In 1979, the World Health Organization announced that smallpox had been eradicated after a ten-year program that vaccinated all the people in every country where the disease was reported, no matter how remote. Somalia was the last country to report a victim of the disease.

Europeans carried their diseases to the New World, but what did they get in return? Syphilis is a disease that swept across Europe just after the first conquistadors returned from the Americas, and scurvy haunted the lives of explorers on the sailing ships that followed.

Syphilis, a sexually transmitted bacterial disease, is usually blamed on someone else. The Italians called it the Spanish disease, the English called it the French disease, the French called it the Italian disease, the Russians called it the Polish disease, the Arabs called it the Christian disease, and in India it was known as the foreigner’s disease. Maybe the Chinese had it right—they called it the pleasure disease.

The symptoms of syphilis can be horrific. The first small pellet-like sore emerges three weeks after infection. It appears where the bacterium entered the body, typically on the genitals. The sore may go unnoticed.

The disease disappears for a number of weeks, but then it returns, causing the patient to have an overall sick feeling—sore throat, swollen glands, headache, and tiredness. Sufferers also experience patchy hair loss and a non-itchy rash on the palms of the hands and soles of the feet. Then the disease disappears again and may not come back for years or even decades.

In its final stage, abscesses eat away the nose, lips, bones, and genitals. Sufferers can go blind, lose their coordination, become paralyzed, or experience dementia before they die. Mothers can pass on the disease to their unborn children. Today, thankfully, we can treat the disease with antibiotics.

There are different theories to explain how syphilis spread to the Old World. In one story, which takes place in 1493, Charles VIII of France marched an army down the Italian peninsula to claim the Kingdom of Naples. He hired Spanish soldiers, fresh from Columbus’s voyage, to enlarge his force. These Spaniards socialized with local women and passed on syphilis, which they’d contracted in the New World. The disease spread quickly and savagely because the Europeans carried no resistance.

Eventually, Charles had to retreat—and he died of syphilis in 1498.

Other scientists now think that the disease probably didn’t come from the New World. Late-stage syphilis leaves scars on the skull, but no such telltale signs have been confirmed on New World skeletons. As well, in a monastery in England, syphilis scars have been found on skulls that date seventy years before Columbus’s voyage. Hmmm—now we’re blaming the English…

Syphilis probably mutated into a sexually transmitted disease from a milder related disease called yaws, which afflicted ancestral humans. It’s likely that all the moving around that happened during Columbus’s explorations and Charles’s war spread this new Old World disease.

When Columbus returned from the Americas with his stories of exploration, healthy young men from all over Europe signed up to serve their countries in discovering or protecting newly claimed lands. Many of these sailors dreamed of adventure, the wonders of the world, and the possibility of riches. They understood the risks of enduring storms in a wooden sailing ship, getting lost, and shipwreck, but they looked forward to the challenge of facing the elements using their wits and muscles in a team effort. Fun!

After a few months at sea, some sailors found that—instead of getting stronger with the exercise and experience—their muscles weakened and they lost the will to work. They crawled into their hammocks to rest and even die.

Scurvy creeps over its victims slowly. Its first symptoms include gloominess, listlessness, and physical exhaustion. Sufferers lose coordination, their skin bruises easily, their joints ache, and their hands and feet swell.

After a month or more, their gums become spongy and bleed, and their teeth fall out—and so do their nails and hair. Skin turns yellowish and rubbery. Bleeding under the skin leaves purple blotches. Healed broken bones separate again. Old scars gape open and bleed. In the late stages of the disease, the simple action of sitting up quickly can rupture an internal organ and cause the victim to bleed to death.

The sleeping quarters below deck on these sailing ships filled up with the sick—it looked like an epidemic. But scurvy is not an infectious disease. It’s a nutritional deficiency of vitamin C—a fact that no one understood at the time. Without vitamin C, or ascorbic acid, our bodies cannot make the protein collagen, which binds and connects our tissues and bones together.

We get vitamin C mostly from certain fresh foods, with high doses in fruits such as lemons, oranges, and limes, and in vegetables such as spinach, broccoli, and parsley. A standard ship’s diet of biscuit, cooked and salted meat or fish, and beer contained zero vitamin C.

Portuguese explorers and privateers knew that drinking a few swigs of lemon juice every day kept scurvy away as early as 1397—but that practice disappeared by the early 1600s. The idea of preventing a disease that had not yet erupted made no sense to sea captains—especially if they had to pay for expensive lemon juice.

Meanwhile, European doctors looked for cures using the classical theory of the humors—imbalances in the body’s yellow bile, black bile, phlegm, and blood. Scurvy could be balanced, some thought, by spooning vinegar into the mouth. Others recommended a strong laxative to empty the bowels or a poisonous patent medicine called Ward’s Pill and Drop which caused violent sweating, vomiting, and diarrhea. Over the next two hundred years, tens of thousands of sailors died of scurvy.

In 1747, a young English ship’s surgeon named James Lind sailed on the HMS Salisbury, a ship cruising the English Channel, looking for invading Spanish warships. It wasn’t long before eighty of the crew fell seriously ill with scurvy. Lind persuaded the captain to allow him to run an experiment to see which of six supposed treatments could cure scurvy. Surprisingly, the captain agreed—but the sailors did not. No matter! Lind hung the hammocks of twelve of the sickest sailors together in a separate hold and fed them all the same kinds and amounts of food—gruel, broth, biscuit, barley, rice, dried currants, raisins, and wine.

The men continued to be very sick while eating this diet. He then divided the men into pairs and added one “cure”—cider; vinegar; elixir of vitriol; sea water; two oranges and a lemon; or a medicinal paste of garlic, mustard, and tamarind—to the diets of each pair. After two weeks, the two men who had eaten the oranges and lemon were up and helping tend the sick. The two on cider rations felt better but were still too weak to work. All the other sailors had become sicker.

Despite Lind’s results, only a few ships’ captains followed his recommendations. Those who prescribed citrus defeated scurvy on board—including Captain James Cook during his voyages of discovery in the Pacific Ocean—and those who did not often lost more men due to scurvy than any other cause, including battle. But the obvious statistics were ignored.

In 1793, Sir Gilbert Blane, a physician but also an aristocrat, advised his friend, an admiral on the warship HMS Suffolk, to give a daily dose of lemon juice to all the sailors on their voyage to the East Indies. After more than twenty-three weeks at sea, scurvy claimed no lives. Using this example as well as statistics that compared death by scurvy to death by enemy action, Blane persuaded the British Navy to adopt citrus rations for all sailors—earning them the nickname “limeys.”

It is interesting to note that Native Canadians had a cure, too. When French settlers came to Canada and stayed through winter, they had no fresh fruits and vegetables to eat and suffered from scurvy. The Native Canadians shared their remedy—tea made from fresh spruce needles. Spruce needles are richer in vitamin C than lemon juice! Those who drank the tea got better.

In 1793, when Stubbins Ffirth was nine years old, yellow fever killed five thousand people in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Nine years later, as a young medical student at the University of Pennsylvania, Ffirth set out to demonstrate that yellow fever is not contagious. He’d noticed that caregivers of the sick did not necessarily get sick themselves and reasoned that yellow fever spread in another way.

A unique and startling symptom of yellow fever is black vomit. So Ffirth chose to sleep in bed sheets covered in the black vomit of a yellow fever victim. He did not get the disease. Next, he cut his arms and rubbed black vomit into the wounds. He did not get yellow fever. He dropped black vomit into his eyes—no reaction. Then he heated up some vomit and inhaled the fumes. When that didn’t make him sick, he ate the black vomit. Still healthy, he covered himself in the blood, saliva, and urine of yellow fever victims, and when he continued to remain well, he felt he’d proven the disease is not contagious. There was one big problem, though—people didn’t believe his story (or that his name had two f’s in it).

But Ffirth was right. We now know that humans catch yellow fever from the bite of an infected mosquito, Aedes aegypti, and not from contact with other people.

Yellow fever attacks a victim’s liver, causing jaundice, which turns the skin yellow. Sufferers experience very high fever, headache, back and leg pain, and terrible vomiting. The vomit is black because victims bleed into their stomach, where the blood darkens. For a long time, people called this disease the black vomit.

Yellow fever probably originated in Africa and crossed the Atlantic to the New World on slave ships. When smallpox and other Old World diseases killed off so many Native Americans, ruthless coffee and sugar plantation owners brought in Africans to do their backbreaking labor—free slave labor, at that.

The mosquito that spreads the yellow fever virus can survive on sailing ships by laying its eggs in water casks. The insect can thrive for several generations at sea, picking up the virus from the blood of sick passengers and passing it on to new victims on board. Finally, both mosquitoes and sick passengers disembark and infest new populations.

Mosquitoes die off in winter in cold territories—like the Northern United States and Canada—but they thrive year-round in warm climates.

In the New World, terrible outbreaks occurred in Jamaica, Cuba, Haiti, and ports up the Eastern Seaboard as far as Quebec. Native Americans, Europeans, and Asians died in large numbers in these places. Africans who had just disembarked from the slave ships seemed to be more resistant, and so—in a cruel twist—the slave trade increased. When the slaves in Haiti rebelled against French plantation owners in 1802, Napoléon Bonaparte’s army was unable to win the island back because so many of his troops died of yellow fever.

The next year, the French sold Louisiana to the United States because a huge number of their colonists in New Orleans had died from yellow fever. An attempt by the French to dig the Panama Canal had to be abandoned in 1893 after twenty-two thousand workers died. In order to protect their workers from insects, the French had tried placing the legs of their beds in water—only to provide a perfect egg-laying habitat for mosquitoes and increase the death count!

When yellow fever first appeared on the Eastern Seaboard, people blamed sick oysters, the smell of dead fish, thunderstorms, earthquakes, godless living—you name it! They tried spreading quicklime or coal dust in the streets and igniting bonfires to prevent it. They thought bloodletting, dunking in ice water, or drinking lemonade might cure it.

Some noticed that yellow fever clustered around ships and dockyards—but that it didn’t seem to travel inland. Others started to acknowledge, like Ffirth, that the people who took care of the sick didn’t always get sick themselves, realizing that yellow fever wasn’t contagious.

About eighty years after Ffirth’s experiments, Carlos Finlay, a Cuban-born doctor, proposed that mosquitoes transmitted yellow fever. He conducted 104 experiments in which volunteers were exposed to mosquitoes that had bitten yellow fever victims—but none of his volunteers got sick.

When Dr. Walter Reed, an American army major and physician, joined Finlay in Cuba in 1900, he tried another experiment. Reed lengthened the amount of time between when the mosquito was exposed to the disease and when it was released on the volunteer—and he found that those volunteers did get sick. His work was called “silly” in newspaper editorials back in the United States.

Reed contrived another experiment to prove this theory. He set up volunteers in three screened areas. In one, volunteers slept in the soiled pyjamas of yellow fever victims on black vomit—covered bedding. Into the second, he released mosquitoes that had recently bitten yellow fever victims. In the third enclosed area, volunteers remained without mosquitoes or soiled pajamas.

Only the volunteers exposed to mosquitoes got yellow fever. The volunteers who slept in smeared pajamas on black vomit—covered beds were held there for sixty-three days—and they still didn’t get sick!

Although Reed did not produce a cure for yellow fever, he showed that by controlling mosquitoes he could protect people from getting the disease. His findings enabled the Americans to complete the construction of the Panama Canal in 1914 with no deaths caused by yellow fever.

Max Theiler, a South African virologist working in New York, finally perfected a vaccine for yellow fever. He won the Nobel Prize for medicine in 1951 for his work.

One question—why did Ffirth not contract yellow fever when he cut his arms and rubbed black vomit into the open wounds? His actions were similar to a mosquito injecting virus into the bloodstream with her bite. Scientists think that the vomit of dying yellow fever patients does not contain a lot of active virus—Ffirth was just lucky!

In 1634, King Charles I of England suspected that a certain old woman who practiced the healing arts was, in fact, a witch. He ordered Dr. William Harvey, his personal physician, to investigate.

The doctor traveled by carriage to her hovel. At first, the old woman wouldn’t let Harvey in, but he cajoled her, explaining that he was a wizard and wanted to meet her familiar, a supernatural being that acts as a witch’s helper. Harvey assumed that her familiar would be a cat. Impressed by the doctor’s charm and courtly wig, she opened her door and directed him to a cupboard—and out hopped a toad. The old woman offered her toad a saucer of cream.

Harvey gave the woman a coin and asked her to walk to a local inn to bring him back some beer. When she left the hovel, Harvey grabbed the toad and cut it open. He examined its heart, lungs, and intestines. He decided it was not supernatural, just a common toad.

When the woman returned with the beer, she saw that he’d killed her toad. She shrieked, hit him hard, pulled his wig, and scratched his face. Harvey escaped to his carriage covered in cuts and bruises.

Dr. Harvey was no ordinary physician. Years before his dissection of the toad, he wrote about the function of the heart and circulation of blood in humans. His work contradicted the theories of the fathers of medicine—especially Galen of Pergamon—and was dismissed by many of his colleagues. However, the king supported him, and so—eventually—did future generations. A man of science, Harvey still had to cut open a toad to prove that it wasn’t supernatural. He lived in a time when the medical world see-sawed between belief in tradition, even superstition, and belief in scientifically tested observation.

In the Age of Discovery, Europeans celebrated the finding of new lands and peoples but were slow to accept fresh ideas or discoveries in medicine. Most doctors were not like Harvey. They clung to the traditional theory of the humors. Other folk on the fringes of the medical world, like the old woman, based their practices on superstition. But medicine founded on scientific evidence did take a few steps forward in these years—including the acceptance of vaccination for smallpox and the citrus supplement for scurvy. Some new theories were developed too—and survived the test of time either in alternative or mainstream medicine.

One was the theory of plant signatures. Patterns in nature fascinated Jakob Böhme in the seventeenth century. He suggested that plant parts that resemble body parts could be used to treat complaints. For example, the liver-shaped leaves of mayflowers would help treat liver diseases. Walnuts, which look like brain matter, could cure headaches. These theories excited the medical community for a while and continue to interest herbalists today.

In the eighteenth century, Samuel Hahnemann proposed a theory of similarities. He said that “like” would cure “like.” So an onion that causes a runny nose cures the common cold. Hahnemann’s theories and medicines developed into present-day homeopathy.

In the sixteenth century, Girolamo Fracastoro of Verona suggested that disease had nothing to do with humors. He proposed that disease entered the body as seeds. These seeds then multiplied and caused illness. This led him to note that different diseases had different seeds—an early theory of germs. He recommended personal and public hygiene to prevent disease. Fracastoro’s ideas were generally ignored until, in 1675, Antony van Leeuwenhoek created a microscope lens powerful enough to actually see some of these seeds, or germs. Real evidence proved this theory—and today Fracastoro’s ideas are part of mainstream, science-based medicine.

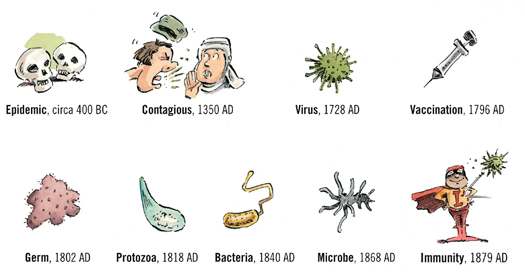

Little by little, doctors began to look at contagions in new ways. We can track the slow modern understanding of contagious disease by looking at when people started using existing common words to describe medical issues: