During our layoff period at Columbia in the mid-’40s, we were contracted by the owners of a small, rather rundown theater in New Orleans who wanted us to play on their bill. They turned out to be the Minskys of burlesque fame. Harold Minsky, who was a true showman, was attempting to change over a small house to vaudeville and wanted to get name acts that would draw customers. His mother and father were operating the theater while Harold took care of booking the acts.

Ludicrous as the situation may seem, the elder Minskys had not been on speaking terms for many years. If Mrs. Minsky wanted to say something to her husband, she would do it through Harold: “Tell that idiot to stay in the department, where he belongs.” Then Mr. Minsky would reply through Harold, “Tell Mrs. Idiot to mind her own part of the business.” As if Harold didn’t have enough to worry about, he had Mr. and Mrs. Minsky.

Minsky’s theater was set up so that at the back of the last row of seats a section was set aside for standing room, where about eighty people could be tightly wedged together. There was an exit door at each end of this section, with a crash bar across the door in case of fire or other trouble. In the front of the theater were six steps the width of the front, which was about sixty feet wide. Flanking the steps were guardrails; to the right was the box office where Mrs. Minsky sold her tickets. Behind was another box office with a cashier who sold tickets to blacks only. Remember, this was New Orleans, and black people could sit only in the gallery.

When Harold Minsky asked the Stooges to play his theater—I took care of the business for the act—I replied, “Our salary has gone up since the old days. We now get forty-five hundred a week.”

Harold said, “I need you fellows very badly. What kind of a deal can you make me?”

I told him, “Harold, you guarantee us fifteen hundred dollars. We’ll get four acts for you, and you give us a fifty-fifty split from the first dollar above our fifteen hundred.” Harold thanked me profusely for giving him a break. I then realized after making the deal that the only way we would do good business was to create a maximum amount of audience turnover. I found the answer to this problem after the first performance. I announced to the audience that if they would line up at the stage door in the alley next to the theater, we would give each person a picture. Although it was raining like mad outside, our loyal fans lined up just to be able to get an autographed photo. Meanwhile, the house had cleared and another group was packed in.

That was a week to remember. Mrs. Minsky sold tickets in the front box office, and I recall standing out front one day. A woman saw me and said to her friend, “That’s the ugly one who hits the two nice Stooges.” Her friend replied, “Don’t talk like that. He just keeps the other two guys in line, like my Albert does with our two boys.” Mrs. Minsky’s face beamed as the people kept pouring in: “Moe, I have a sneaky feeling that we’re going to make a lot of money.” Then, a large, swarthy woman stepped up to the box office and asked for two adult tickets and three juniors. The woman was carrying a child completely covered by a blanket. Mrs. Minsky reached out and uncovered the child, who turned out to be a boy of fifteen—with a mustache yet. Mrs. M. was a tough old bird, and at one point when the theater was jammed, she kept urging the people to come in, saying that there was plenty of room inside. It was so packed that one man who was already inside was shoved to the outside by the crowd and was forced to buy another ticket to get in again.

That week we gave away a grand total of thirty thousand pictures and did $15,000 worth of business. This was fantastic for that size house. The Minskys wanted us back, but our contract kept us from returning.

It was May 14, 1946, a day so indelibly imprinted in my mind. We were just finishing Half-Wits’ Holiday, a remake of one of our favorite comedies, Hoi Polloi. It was a clever, funny film that brought to an end the career of one of the great comics of his time.

Curly sat in director Jules White’s chair waiting to be called to do the last scene of the day, while I was finishing one with Larry. It was terribly humid, and the heat on the soundstage was stifling. Larry and I finished our scene, and the assistant director called for Curly to come in to complete the final scene of the picture. Curly didn’t answer. I went out to get him and found him with his head dropped to his chest. I said, “Babe”—I called him sometimes by his childhood nickname—and Curly looked up at me and tried to speak; his mouth was distorted and speech would not come. Tears rolled down his cheeks, and soon there were tears running down mine. I thought my heart would break. I immediately knew that he had had a stroke. I put my arms around him and kissed his cheek and forehead. He squeezed my hand but couldn’t say a word. I had the studio car take him home while I finished his scene. When Jules finally said, “That’s it. Wrap it up,” I ran to my car without taking off my makeup or wardrobe and drove to Curly’s house.

After Curly’s stroke, I arranged for him to be taken to the Motion Picture Country House in Woodland Hills, where he could get the best of care and therapy. I was with him almost constantly.

Later, when I had time to collect my thoughts, I had the feeling that this would be the end of the Three Stooges. Who could take Curly’s place? He was a genius in his field, kind, considerate, and so carefree and humorous. He drank far too much liquor, and I knew the reason why. After his gun accident as a teenager, he was in quite a bit of pain when he stood too long. The fact that he had to shave his head for the act was also a factor: he felt that he had no longer any appeal for the fair sex. So he drank to give himself the courage to approach any young lady that appealed to him.

Curly remained in ill health for six years, having additional strokes, and passed away in January 1952 at the age of forty-nine.

Larry and I wondered if it was possible to revive the Three Stooges. Many performers were presented to me by agents, but they didn’t have a tenth of what was needed to fill the bill. Finally it hit me: why not Shemp! He had been one of the Stooges before Curly. I presented the idea to Columbia, but the front office felt that Shemp looked too much like me. So I told them it’s Shemp or you don’t have the Stooges anymore at Columbia. They quickly changed their minds, and Shemp once again joined the act. The Stooges were back in business again. I felt very low for a long time but never snowed it. Every time I smacked or poked Shemp I was seeing Curly. This feeling finally left me and I was able to think clearly again.

The first two-reeler we did with Shemp back as one of the Stooges was Fright Night, in which we play fight managers. Ed Bernds directed that one. Later, when we made Hold That Lion!, Curly came back to do a brief gag appearance. It was the only film in which all three of us Horwitz brothers appeared.

Shemp is back with the Stooges and gets a roaring welcome in Hold That Lion! (1947).

Moe, as St. Peter, tells Shemp he can’t enter the Pearly Gates until he reforms his fellow earthbound Stooges, as Marti Shelton takes notes in Heavenly Daze (1948).

In Heavenly Daze, the boys demonstrate one of their utensils to a vaguely interested Victor Travers and Symona Boniface.

Vagabond Loafers (1949) has Shemp doing the role Curly had played in an earlier version of the film (A Plumbing We Will Go).

Shemp and Moe, in Dopey Dicks (1950), congratulate themselves on foiling the villains, although Stanley Price has a surprise for them.

The boys take a break in their search for missing pearls in Hugs and Mugs (1950).

The Three Stooges as broads in Self Made Maids (1950).

In Self Made Maids, Larry helps Moe put the finishing touches on his makeup.

Larry, Shemp, and Moe display their ingenuity as census takers in Don’t Throw That Knife (1951).

The Stooges, director Edward Bernds, and Hugh McCollum accept the 1951 Exhibitor Laurel Award, presented to Larry, Shemp, and Moe.

Moe and Helen in front of their Toluca Lake home with Helen’s cousin Rosalie and sister Clarice in 1952.

In 1955, Helen and I decided to sell our home in Toluca Lake and go on a cruise to Europe. Our stay abroad lasted about four months. These were happy days, but my happiness was short-lived.

November 23 started as an ordinary day. Shemp had gone to the horse races in the afternoon and to the prize fights that night. All of Shemp’s friends got a kick out of his reactions to the fights. He would jab, jerk, and duck in his seat, reacting to the fighters in the ring. The audience would watch him as much as they watched the fight. People sitting on either side of him would often get up and change their seats to avoid jabs in the ribs from Shemp’s wild blows. After the fights, Shemp got into the car of one of his friends and was telling jokes when he suddenly dropped his head, leaned against one of the men, closed his eyes, and, with a smile on his face, died.

When I heard the news that night, I was dumbfounded. I had such a feeling of loneliness and frustration. It took me weeks to gather my thoughts, to make plans for the future, and to try once more to put the act together again. I don’t know what I would have done without Helen’s encouragement, for at that moment I wanted to give it all up.

Daffy detectives Moe, Larry, and Shemp again get themselves entangled in offers to solve a mystery in a haunted castle in Scotched in Scotland (1954).

Hugh McCollum and Christine McIntyre pose with the Stooges in Scotched in Scotland before the boys embark on their de-haunting of the castle.

The boys’ adventures in a Scottish castle put them close to Christine McIntyre, one of their frequent leading ladies, in Scotched in Scotland.

The boys borrow blacksmith Jock Mahoney’s anvil for devious purposes in Knutzy Knights (1954).

Philip Van Zandt and assorted baddies menace Moe, Larry, and Shemp in Knutzy Knights.

Inept restaurateurs Shemp, Moe, and Larry tangle with gangsters Kenneth MacDonald and Frank Lackteen in Of Cash and Hash (1955).

In Blunder Boys (1955), our heroes are at war with the army, and the surrender is unconditional.

Shemp tries to impress Moe in Gypped in the Penthouse (1955) under the disapproving glare of gold digger Jean Wiles.

Shemp, Moe, and Larry play their own sons in Creeps (1956).

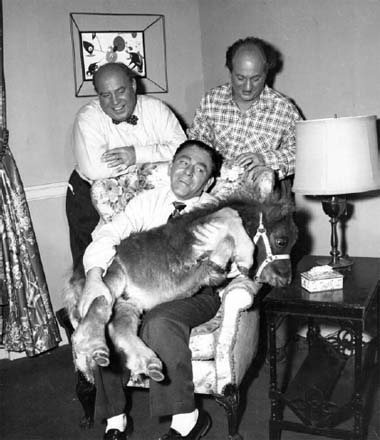

Helen and Larry urged me to go on with the act, and I slowly brought myself around to finding a replacement. I started out by trying to get Joe DeRita to take Shemp’s place. I knew Joe’s work from burlesque. He was fat and chubby with a round, jovial face, and, with his hair clipped close, he would look a great deal like my brother Curly. I went to see him and put the proposition to him. He told me he’d like nothing better than to get out of burlesque and join the Stooges. “But Harold Minsky has me under contract.” No matter how much Larry and I pleaded with Minsky, he would not turn Joe loose. I could readily see why. Joe was the best comic he had. Now what to do?

I then recalled that Joe Besser, another chubby burlesque comic, had made several pictures at Columbia on his own and was known to television viewers for his stooging on Milton Berle’s show. He, too, said that he would love to join the act except that he owed Columbia another two-reel comedy on his contract, but I talked the studio into releasing Joe from the deal and letting him join the Stooges.

The first short with the “new” Three Stooges was Hoofs and Goofs, in which our “sister”—played by Harriette Tarler—is reincarnated as a horse. In 1958, after making sixteen more two-reelers with Joe Besser, all directed by Jules White, we completed our contract with Columbia. Now what? Joe informed us that he could not go on tour with us, since his wife was ailing. Once again, a crisis in the Stooges’ careers.

Larry, Joe Besser, and Moe confuse even themselves as identical triplets in A Merry Mix-Up (1957).

Joe Besser’s flair as a chef dismays Moe and Larry and their dates—Ruth Godfrey White, Jeanne Carmen, and Harriette Tarler—in A Merry Mix-Up.

Joe, Larry, and Moe try to convince their sister-turned-pony that she won’t go to the glue factory in Horsing Around (1957).

A musical Stooges interlude in Guns A Poppin! (1957) before the boys depart for a cabin in the woods.

The boys survey an escape route in Pies and Guys (1958) while unfriendly Milton Frome counts to three.

Moe blows his top in Fifi Blows Her Top (1958), as Joe and Larry try to keep him contained and Vanda Dupre, Harriette Tarler, Diana Darrin, and Joe Palma look on.

Moe and Larry bid farewell to Joe Besser.

Here we were with an act that still had the potential to earn us a living—if not in films, then in personal-appearance tours—and even though it seemed hopeless, I just couldn’t let this happen. I had put so much into it through the years. Where to turn? What to do? I remembered Minsky had Joe DeRita. It couldn’t hurt if I tried him again. To my surprise he said, “Moe, I’m in luck. My contract with Minsky is over next week, if you still want me.” I said, “Joe, you’re in. We’ll start rehearsing with you next Monday.”