At the outset of his Persian wars and during the four years that followed, Alexander had an able and reliable second-in-command in the person of Parmenio, who had been Philip’s trusted general and had led the Macedonian forces on the Asiatic coast against the Allies of Athens. In Alexander’s battles, Parmenio regularly commanded the defensive left wing cavalry. He is often represented as giving Alexander advice – which Alexander nearly always rejected.

Parmenio’s three sons also served with the Macedonian army under Alexander, Philotas as a dashing young cavalry officer, Nicanor in command of infantry, while Hector was probably still too young for any command. Sadly, Hector lost his life by an accident on a Nile boat, and Nicanor died in the East. Even more tragic ends, with probably unmerited disgrace, awaited Philotas and Parmenio himself. After their death, other officers such as Coenus and Craterus came into prominence, not to mention Seleucus and Ptolemy who, with others, were to be the heirs to Alexander’s conquests.

The life of Hephaestion was almost coextensive with Alexander’s own life, and he retained Alexander’s confidence and affection throughout. Yet he was never a distinguished commander in battle, being mentioned mainly in connection with ancillary services, transport and communications. When he died at Ecbatana in 324BC, Hephaestion left a sorrowing Persian widow and was given a magnificent funeral.

The Persian generals who confronted Alexander in north-west Asia (Arsames, Petines, Rheomithres, Niphates and Spithridates) were slow to mobilize in the face of the Macedonian threat, but Spithridates and other Persian commanders showed impetuous courage in battle. In this respect, they differed from Darius himself, who for all his elaborate warlike preparations, fled from the battlefield precipitately as soon as he was personally threatened.

The Persians were initially aided by Memnon, a commander of Greek mercenaries, brother of that Mentor who had helped to reconquer Egypt for the Persian Empire. Persian jealousy of Memnon, however, led to divided counsels before the Battle of the Granicus.

Alexander had inherited from his father the army he led into Asia. On the battlefield, it consisted mainly of three formed bodies: an assault force of right-wing cavalry, defensive left-wing cavalry, and a central mass of infantry pikemen operating usually in contact with those other substantially equipped foot-soldiers known as ‘hypaspists’. (A hypaspistes was originally a shield-bearer – often a slave. The word could also refer to a king’s honoured armour-bearer. It applied in an honourable sense to Macedonian infantrymen.) To these were added, frequently in wing positions, lightly-armed skirmishing troops – archers, slingers and javelin-throwers. The way in which all these troops were used emerges in the study of individual battles. The élite ‘Companion’ cavalry were mainly Greek-speaking Macedonians and they were supported by other non-Greek Macedonian horse squadrons (Paeonians from northern Macedonia) and lancer scouts. Thracian and Thessalian horsemen often served with Parmenio on the left wing.

This illustration is copied from a silver coin in the British Museum. It is struck in the name of the Persian king, as lettering on the reverse indicates. The head-dress again exhibits the typical side flaps, but it is secured with a band or filet. We may perhaps compare it with that worn by the figure on the extreme right in the Issus Mosaic.

Specimens of Greek helmets that have been recovered are mostly (not all) of simple design, and the aesthetic appeal is functional. More ornate and often highly decorated types certainly existed. Helmets were usually of bronze, but that worn by Alexander at Gaugamela was made of iron and polished to shine like silver.

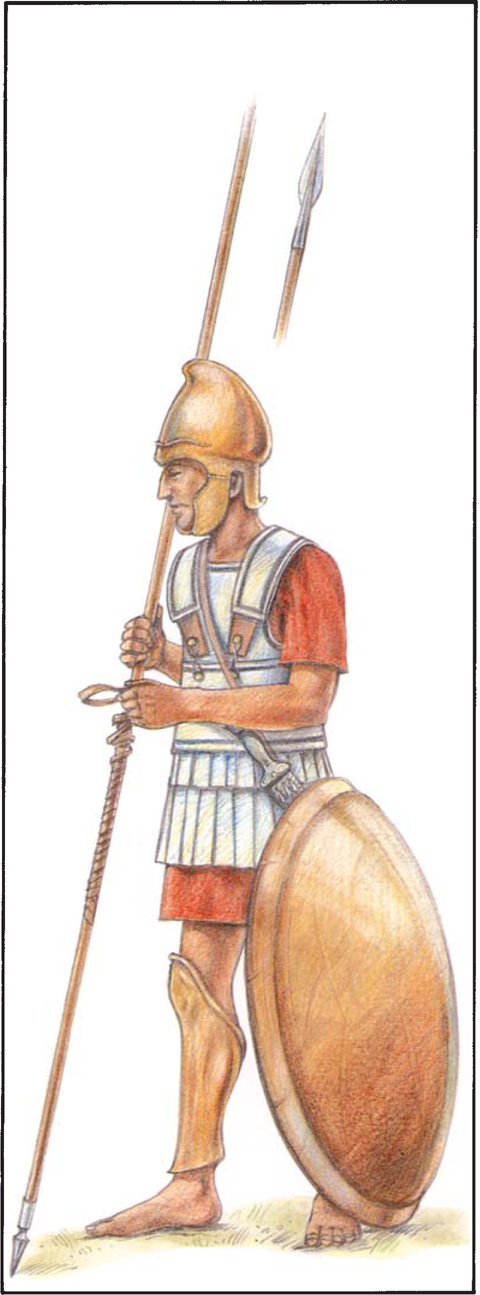

A Macedonian hypaspist guardsman. The exact nature of these troops is not clear, but it seems probable that they were lighter troops than the phalangists and protected the vulnerable flank of the phalanx in battle. (Painting by Richard Geiger)

The Companions were protected by metal helmets and partially metal corselets, but carried no shields. Horsemen of other contingents were more lightly equipped. The helmeted infantry pikemen wore bronze greaves and carried small shields which they manipulated on their forearms. The hypaspists, (sometimes translated ‘Guards’), were spearmen who carried conspicuous shields. Both they and the pike soldiers were sometimes described as ‘Foot-Companions’. Both were Greek-speaking Macedonians – if allowance be made for an uncouth dialect.

The Companions, whether cavalry or ‘Foot-Companions’ were recruited from Macedonian localities on a territorial basis. Each was therefore the ‘companion’ of his neighbour in arms, as of the king or commander whom he served. In which sense the word originally applied is not certain.

Swords in scabbards were carried by most Greek and Macedonian infantrymen as reserve weapons. The shafts of spears and pikes might easily be broken, and even archers could at any time find themselves closer to the enemy than they had bargained for. By Alexander’s epoch, the slashing sword (‘kopis’ or ‘machaira’) had become common.

A Persian ‘Apple-bearer’ Royal foot guard equipped with a brown leather, bronze-studded cuirass, a Greek-style bronze shield and a Persian infantry thrusting spear counter-weighted by the golden ‘apple’ that gave the unit their name. (Painting by Richard Geiger)

Greek sculptors and painters mingled realism and convention in their portrayal of mythological subjects. This statue represents Eros (Cupid) bending his bow; Cupid’s use of the leg, with a slightly crooked knee, for testing or stringing a bow was probably normal practice in Alexander’s time.

This Persian soldier, from a fourth century vase, is an attendant of King Darius, splendidly dressed in embroidered clothing. His shoes, unlike most ancient Greek footwear, cover the toes. His cap with its side flaps is typical of those worn by the Persians and other non-Greek (‘barbarian’) nations. It is probably cut to shape from the skin of a small animal, the lappets being trimmed from the legs of the skin. When drawn scarf-like across the chin or lower part of the face, these flaps would give protection in battle or hunting, or against flying dust. (Compare with the Issus Mosaic.)

Other Macedonians, from the wilder and more remote parts of the territory, served as skirmishers and missile fighters – as already described. They relied for defence on their own unencumbered agility, some of them using light shields. Most troops carried swords in scabbards as weapons of last resort.

Alexander of course led with him Greek and Thracian allies. Greek mercenaries were always available to any general that needed them.

The main strength of the Persian troops who opposed Alexander lay in their horsemen and bowmen. Archers were in fact often mounted, in which case they were protected only by tunics and breeches of quilted material. Heavy cavalry wore corselets, which sometimes resembled those of the Greeks but sometimes were made of soft material faced with metal scales.

Various types of ancient spear. One shows a butt weight fitted for balance. The loop attachments in the next have been interpreted as appendages to assist a horseman in mounting, but more probably the shafts in the original ancient reliefs were intended as those of javelins, and the loops are thongs such as were used by javelin-throwers to gain distance and force. Alexander made good use of javelin-throwers when confronted by Porus’s elephants.

For infantry, the Persians relied much on Greek mercenary hoplites. They also had their own heavy infantry, probably armed in imitation of the Greek hoplites (called Cardaces). Lighter infantry used spears and thrusting swords, and relied on quilted clothing for body protection. The many national contingents from the far-flung Persian empire probably had no equipment save their ordinary hunting weapons.

It is very hard to judge how far Alexander’s ambitions, at any particular time and place, had already taken shape. One can only stress again that he believed in consolidating his conquests before proceeding to any fresh venture.

His first professed purpose was to liberate the Greek cities of Asia. Later, while he was still subduing the Phoenician cities of the Syrian and Palestinian coast, he stated in a letter to Darius that his aim was to avenge Persian invasions of Greece in the past. Darius offered to cede to him the Persian western dominions, but he rejected the offer, and he was obviously bent in 332BC on invading Mesopotamia.

When this was accomplished he was still unsatisfied. His purpose was to capture the fugitive Darius, and this gave him the pretext for invading the north-east provinces of Persia. It is particularly hard to know whether his aim of blending Persian and Greek civilization and culture should be regarded as an expedient for pacifying conquered territory or a visionary ideal for the political future. Indeed, his motives, as often, may have been mixed.

In 327, when he crossed the Indus and pressed on beyond the frontiers of Darius’s empire, his motives can only be explained as marching and conquering for the love of marching and conquering. It is a miracle that men followed him as long as they did – but even Alexander’s army rebelled in the end.

It cannot of course be said that Alexander’s enemies had any positive or expansionist war aims of their own. Their purpose was merely to defend themselves against him. In this, all ultimately failed. In all cases, the only alternative was to recognize him at the outset as a friend and ally, offering a contribution of men and materials to his ongoing wars. Even to a conquered foe, Alexander could be generous, but he could also on occasion be extremely savage and vindictive.

The Greek ‘himation’ could be used equally as a cloak or blanket. The accompanying illustration from a Greek vase shows a soldier in marching order, his ‘himation’ fastened with a clasp over his chest. On his head is the broad-brimmed felt hat known as a ‘petasus’. His footwear is notably substantial and the leggings are separate from the shoes – the uppers of which are supplied by latticed thongs. Despite the barefooted warriors commonly depicted in battle scenes, it is clear that an ancient army could expect to march well shod.