CHAPTER 3

Going Global

The Industrialization and Consolidation of Agriculture and Food Production in the United States

From Craft Production to Mass Production

Large-scale, factory-like farms account for the bulk of food and fiber produced in the United States today. The mass production of food has articulated with mass consumer markets to offer consumers relatively inexpensive, standardized products. The range of agricultural commodities produced in America has been narrowed considerably in the past hundred years to bulk commodities such as wheat, corn, soybeans, a few varieties of fruits and vegetables, and a handful of genetically similar breeds of livestock and poultry. At the same time, the “system of agriculture and food production” has taken on a new spatial pattern as well. At the beginning of the twentieth century many regions of the country were fairly self-sufficient in producing the commodities their residents consumed. Today, however, consumers depend upon many imported products that can be produced only in climates and soils outside their region or even the nation.1

Several long-term trends have shaped America's food and agricultural system over the past hundred years. First, farm numbers have steadily declined. In 1910 there were nearly 6.4 million farms in the United States. Today, there are fewer than 2 million. Second, production has become concentrated on a small number of very large farms. And the most highly industrialized farms are clustered together in “agricultural pockets” throughout the country. At the same time, regions of the country that at one time produced substantial amounts of agricultural products have seen farming all but disappear. Third, farms in every region of the country have become increasingly specialized, many producing only one or two commodities for the market. And fourth, with the exception of some dairy products, including fluid milk and specialty produce, the linkages between local production and local consumption have been broken for virtually all commodities. Not only are large amounts of fresh fruits and vegetables, meat, and processed dairy products being shipped great distances, but once vital local food-processing sectors have all but vanished from most regions.2

The Trend toward Concentration and Consolidation

The information in tables 3.1 and 3.2 illustrates some key structural changes in U.S. agriculture between 1910 and 1997. The data in these tables tell a story of a dramatic transformation of agriculture from a system that was comprised of many farm operators who produced a broad array of commodities on relatively small plots of land to a system of production in which a handful of very large-scale, specialized producers now account for the bulk of sales. For example, the average farm size in the United States increased slowly between 1910 and 1950, from 138.1 acres to 215.3 acres, but then accelerated after 1950. Today, the average farm is close to 500 acres.

Table 3.1. Farm Structure Information and Enterprise Diversification on U.S. Farms: 1910, 1950, 1997

Sources: Thirteenth Census of the United States, volumes 5–7 (Agriculture); U.S. Census of Agriculture, 1950; U.S. Census of Agriculture, 1997.

* Data not available.

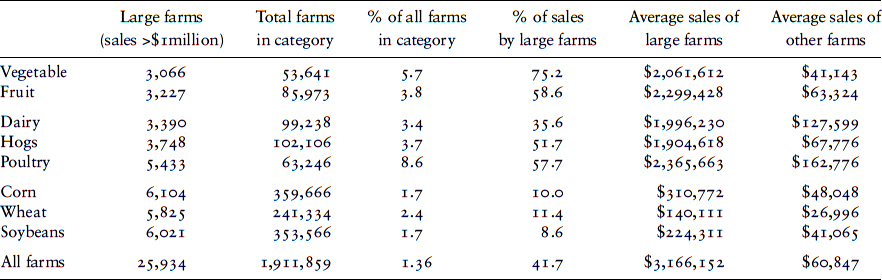

Table 3.2. Concentration of Agricultural Production by Various Commodities: 1997 Census of Agriculture

Source: U.S. Census of Agriculture, 1997.

Large-scale producers in the United States are accounting for an ever increasing share of production. Consider that the number of America's largest farms, those with average sales of over $500,000 a year or greater, grew by over 600 percent, from 11,412, to 68,794, between 1974 and 1997. During this same period, the total number of farms dipped from 2.3 to 1.9 million.

Very large farms are more likely than smaller farms to receive government payments and to be organized as corporations. In 1997, very large farms, those generating over $500,000 a year in sales, comprised less than 3.6 percent of all farms in the country. However, they operated nearly 20 percent of the farmland and accounted for 56 percent of all farm sales.

At the top of the heap are the megafarms, those operations with annual sales of $1 million or more a year. In 1997 there were 25,934 farms in this category. These million-dollar farms represent only 1.4 percent of all U.S. farms, but they produce almost 42 percent of all farm products sold.

Many of these large-scale operations have taken on the organizational characteristics and adopted sets of production practices that mimic the mass-production model of manufacturing.3 The guiding business principles are that production should be concentrated into fewer units to capture economies of scale, machinery should be substituted for labor whenever possible, and an advanced division of labor should replace the multiple and diverse tasks performed by the “typical” family farmer.

As American agriculture became more specialized and more highly capitalized at the farm gate, it also became more highly specialized by commodity and more regionally concentrated. In 1910, almost 90 percent of all farms raised poultry, over 80 percent had dairy cattle, about 70 percent raised hogs, and nearly 75 percent had horses. Even by 1950, significant proportions of American farmers were still engaged in these animal enterprises. However, by 1997, only 5 percent of U.S. farms reported poultry, 6 percent had dairy cattle, fewer than 6 percent raised hogs, and fewer than 20 percent had horses. Most of the horse farms, of course, sold no agricultural commodities but instead served as stables for horseback-riding urbanites and suburbanites.

Similar patterns are also evident for plant agriculture, though extreme concentration is most evident for fruits and vegetables. In 1910, almost 80 percent of American farmers grew vegetables, half of the farms grew potatoes, 46.8 percent produced apples, and around 20 percent produced other orchard fruits such as peaches, pears, plums, and cherries. As late as 1950, American farms still had a diversified portfolio of fruits, vegetables, and grains. But like animal enterprises, by 1997 the production of fruits and vegetables had become very specialized. Today, only 2.8 percent of American farmers are commercial vegetable producers, fewer than one farmer in fifty grows apples, and fewer than one in a hundred supply the country with peaches, pears, plums, or cherries.

Not only has American agriculture become more specialized over the past hundred years, but it has become amazingly concentrated. Take vegetables, for example. There were 53,641 farms that reported vegetable sales in the 1997 Census of Agriculture. But the largest 3,066 (5.7 percent of the total) of these farms, those with annual sales of $1 million or more accounted for 75.2 percent of all vegetable sales in the country. On average, each of these very large vegetable farms sells about $2.1 million every year. Looking at this from the perspective of the small vegetable producer, the 50,575 farms with sales less than $1 million yearly sell on average only about $40,000 of produce each year. Not surprisingly, almost 40 percent of the million-dollar vegetable producers are found in California.4 Other states with a substantial number of million-dollar producers include Washington (n = 189) and Oregon (n = 188) in the Pacific Northwest, Minnesota (n = 113) and Wisconsin (n = 101) in the Midwest, and Florida (n = 210), Georgia (n = 125), and North Carolina (n = 125) in the South. Together, these states account for two-thirds of the vegetables produced in the United States.

Fruit farms exhibit a similar degree of concentration, with 3.8 percent of all farms accounting for 58.6 percent of total sales. Even though there are fruit producers in virtually every state, a small handful of states dominate production. Of the 3,227 farms in the million-dollar-plus sales category, California with 1,909 (58.8 percent of the total) leads the list, followed by Florida with 347 farms (10.7 percent) and Washington with 324 farms (10.0 percent). Average sales on farms selling $1 million or more a year are approximately $2.3 million. On fruit farms with sales of less than $1 million yearly, average sales per farm are only $63,000 a year.

The corn, wheat, and soybean farm sectors still display considerably less concentration than other farm sectors. These farms form the backbone of agriculture in the American Midwest. Not only are there considerably more farms producing corn, wheat, and soybeans, compared with other commodities, but proportionately fewer of them have reached the $1 million sales mark. Further, the percentages of sales accounted for by those farms with $1 million or more in sales (i.e., 10.0 percent for corn, 11.4 percent for wheat, and 8.6 percent for soybeans) are well below those for other commodities.

But times may be rapidly changing for these farms as well. In 1996, the U.S. Congress passed the Freedom to Farm Act. This act was supposed to remove subsidies for grain farmers, ease regulations, and promote exports. In point of fact, it has led to a rapid restructuring of the farm sector.5 Advanced biotechnologies are accelerating productivity. Farmers today are receiving near record low prices for basic commodities, due to overproduction. And the lack of alternative markets is forcing tens of thousands of Midwest farmers out of business. After the current shakeout runs its course, the farms that remain will be much larger in size, in terms of both acreage and volume of sales.

Changing Geography of Production

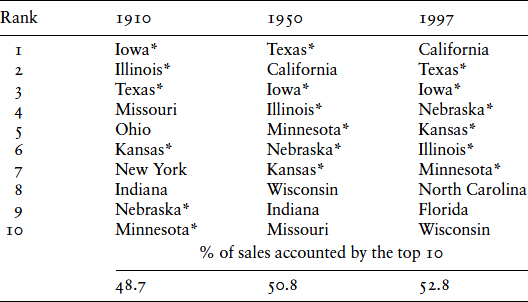

The changing geography of agricultural production is evident in tables 3.3 and 3.4. In 1910 eight of the top ten agricultural states were in the Midwest. Only New York, which produced fruits, vegetables, and dairy products for the booming East Coast cities, and Texas, which was a leading beef and vegetable producer, fell outside of the Midwest. The development of an extensive ground transportation network over the next thirty years made the movement of fresh and processed fruits and vegetables both convenient and economical. By 1997, six of the top ten states were in the Midwest. These states produced most of the bulk commodities that fuel the agricultural economy. The other four states were in the South. And California, which was not a leading agricultural state in 1910, had jumped to the top of the list. Modern transportation, a near year-round growing season, and federally subsidized water combined to make California the nation's agricultural powerhouse. In 1997, California farms accounted for 11.7 percent of all agricultural sales in the United States.6

Table 3.3. Top Ten States Ranked by Agricultural Sales: 1910, 1950, 1997

Sources: Thirteenth Census of the United States, volumes 5–7 (Agriculture); U.S. Census of Agriculture, 1950; U.S. Census of Agriculture, 1997.

* States marked with asterisks (*) were ranked in the top 10 for each time period.

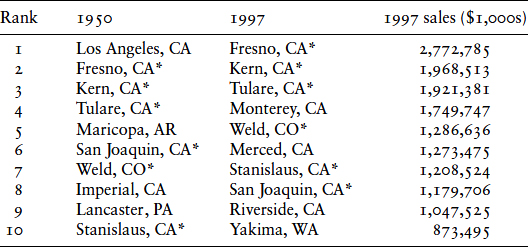

Table 3.4. Top Ten Counties Ranked by Agricultural Sales: 1950 and 1997

Sources: U.S. Census of Agriculture, 1950; U.S. Census of Agriculture, 1997. Counties marked with asterisks (*) were ranked in the top 10 for each time period.

The importance of California's agriculture to the nation's food supply should not be underestimated. Eight of the ten leading agricultural counties in the United States, in terms of sales, are located in California. The largest of these counties, Fresno County, had over $2.7 billion in sales in 1997. There are twenty-two states in which gross agricultural sales are less than Fresno's $2.7 billion.

Distancing: Separating Production and Consumption

Brewster Kneen, a Canadian agricultural economist, uses the term “distancing” to indicate the process that separates people from the sources of their food and replaces diversified and sustainable food systems with a globalized, commodified system. According to Kneen, “Distancing most obviously means increasing the physical distance between the point at which food is actually grown or raised and the point at which it is consumed, as well as the extent to which the finished product is removed from its raw state by processing.”7 The processes of agricultural consolidation and concentration have resulted in a production system that is more often than not separated from where consumption occurs. Modern agricultural and food technologies have contributed to the distancing of food production from consumption in many ways. Plant breeders and other agricultural scientists have engineered stability and durability into commodities. Food processors take basic commodities and manufacture them into products that have very long shelf lives. And food scientists have developed preservation techniques to increase the time between when food is harvested or slaughtered and when it is consumed.8

Most states both import and export agricultural products. Complete agricultural or food self-sufficiency at the state level is probably not desirable, though a provocative paper by Michael Hamm, a nutritionist at Michigan State University, assesses the potential for a localized food supply in New Jersey. As Hamm notes, “If sustainable in the long term implies greater local food production within an ecosystem/community context then we need to see if the potential exists within some area to produce adequate supplies of food.”9 Although New Jersey is the most densely population state in the nation, he points out that there are still approximately 600,000 acres of cropland and 160,000 acres of pasture in the state. Drawing on a broad range of data sources and using a nutritional analysis framework, Hamm concludes that if certain conditions are met, the potential exists for producing all the food needed for the population of New Jersey within its borders.

If a densely populated state like New Jersey has the potential, theoretically at least, to feed all its residents, the prospects for other states to feed their residents must be at least as favorable. In other words, there is probably an untapped potential to relocalize large segments of local food economies.

Control of Farmland

The effects of the industrialization and globalization of agriculture can also be seen in patterns of farmland ownership and control. A global system of food production, one that is increasingly coming under the control of large national and multinational corporations, has begun to refashion how and, more importantly, where food is produced. Driving the global/industrial system of farming is the continual search by agribusiness firms for areas of low-cost production. In a global system of food production, labor and capital flow to places where maximum profits can be extracted. In this system, farmland becomes a “staging area” for the production of food, and given that the supply of farmland exceeds demand, there is little incentive to protect any particular tracts of land from nonagricultural development.10

Land, unlike the other factors of production, is not geographically mobile. However, as capital and labor migrate from place to place, land has the potential to be brought into and taken out of production from one growing season to the next, depending on where maximum profits can be extracted at any given time.

In most nonextractive enterprises, land serves as a “condition” of production in the sense that it provides the space or location for an economic activity (e.g., the land on which a manufacturing plant is situated). For most agricultural activities, however, land is a “means” of production. As the British geographer Richard Munton notes: “For most systems of farming the soil itself provides the growth medium, while acting as a store for capital inputs of varying duration, ranging from the ephemeral (chemical nutrients) to the long term (irrigation systems). As land varies in its fertility and in its relative location, these characteristics confer advantages on some parcels of land at the expense of others.”11

Over the long term, technological advances in the agricultural sciences will continue to raise productivity levels on most farmland around the world. Whether production increases can match growth rates attained over the past forty to fifty years remains an open question at this point. However, over the short term we are likely to see more and more farmland move out of the hands of the people who work it. Absentee landlords are becoming a permanent fixture on the American agricultural landscape.

A global system of agricultural production operates at its highest economic efficiency when the factors of production can be freely substituted for one another. If land can be brought into and taken out of production on a seasonal basis, then it acquires the same degree fluidity as capital, labor, and management. In California, which produces the largest agricultural sales of any state in the nation, for example, the amount of farmland on which the same individual (or set of individuals) was both owner and operator decreased by almost 10 million acres between 1950 and 1997. However, the amount of farmland that was owned by someone other than the operator and leased to the operator by a neighboring farmer or absentee landlord increased by over 1 million acres during this time period. Today almost half of all the land that is in agricultural production in California is absentee-owned.

Similarly, in Texas, the second-largest agricultural sales producer in the nation, the amount of farmland that is owned and operated by the same individual or set of individuals decreased by 21 million acres since 1950, while the amount of rented land increased by almost 7 million acres. Today, over half of the farmland in Delaware, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Louisiana, and North Dakota is owned by someone other than the person who farms it.

It is difficult to empirically evaluate the social and economic consequences of the shift to absentee ownership of large tracts of farmland. Land, which once anchored labor, capital, and management to a particular place and formed the foundation of a family-based system of farming, is increasingly being put into a “reserve pool” from which it can be brought into or taken out of production as global market forces dictate. Control of the food system, then, is shifting from local production and regional and national processing to large-scale, global firms.

Labor Intensification

Until quite recently, agricultural development in the United States has been characterized by abundant land, a steady stream of labor-saving and land-extending technologies, and a relatively scarce pool of labor. The “family farm” mode of economic organization incorporated all members of the household into meeting the labor needs of the farm. When the amount of work became too great for the existing family labor pool, one or two hired hands were added to the farm. However, unlike many nonagricultural enterprises, especially manufacturing, the ability to “efficiently” integrate a large hired labor force into most farm enterprises was constrained by the unique aspects of agriculture. The disjuncture between “labor time” and “production time,” noted by the sociologists Susan Mann and James Dickinson and others, worked against the development of a labor-intensive system of industrial agriculture.12 Don Albrecht and Steve Murdock, rural sociologists at Texas A&M University, note in this regard, “farm production consists of stages that are typically separated by waiting periods because the biological processes involved take time to complete. [And] … unlike production in other industries where commodities are produced continuously throughout the year, crop production is seasonal.”13

Given the difficulty of adapting agriculture to accommodate an industrial-like labor force, one might expect that the amount of hired labor on American farms would remain constant or more likely decline. And, in fact, during most the twentieth century the number of hired workers on American farms slowly, but steadily, went down. However, beginning in the late 1970s and early 1980s, as the first waves of industrialization swept over the agricultural landscape, the number of nonfamily hired laborers began to increase.

Counting farmworkers is a tricky business. Much agricultural work is seasonal. Legal and illegal workers float into and out of the labor force. And government agencies that are responsible for keeping track of the nation's farmworkers do not often agree on basic definitions.14 However, the Census of Agriculture has provided a window that allows for a relatively straightforward comparison of the number of workers per farm in 1950 and 1997. In what is no doubt an administrative fluke, in both of these agricultural census years, data were collected using a similar set of questions. Thus, looking at these data we know that there were 1,555,269 nonfamily workers employed on all American farms in 1950. By 1997, there were 3,352,028. It should be remembered that during this same period the number of farms in the United States decreased by over 3 million.

California, a state whose farmers have led the way down the industrial agriculture path, reported hiring 163,000 farm-workers in 1950. This figure includes full-time, part-time, and migrant workers. By 1997, California farmers were employing almost 550,000 farmworkers. Florida saw the number of hired workers on its farms increase from 67,000 in 1950 to 125,000 in 1997. The additional farmworkers were added during a time that Florida lost over 35 percent of its farmland and nearly 40 percent of its farmers. And North Carolina saw the number of hired workers more than double, from 54,000 in 1950 to 127,000 in 1997. This influx of hired labor occurred at the same time that North Carolina was losing over half of its farmland and over 80 percent of its farmers. In all these cases, the growth of the hired workforce on farms coupled with the decrease in the number of farms and the loss of farmland signaled a change from traditional family farming to industrial-like agricultural production.

In most states it was not the typical family-labor farm that was adding a hired man (or woman) or two to extend its operation and capture some additional economies of scale. Instead, it was a new breed of labor-intensive, industrial-like operators that accounted for the dramatic increase in hired workers. The numbers of farms that employed ten or more hired workers went up everywhere and especially in those states where the industrial model of farming was taking a firm hold. In California there has been a threefold increase in these labor-intensive farms in the past fifty years. Today over 9,500 California farms, each employing on average almost fifty workers, account for almost 85 percent of all hired farm labor in the state. In Florida these labor-intensive farms also average over fifty workers and account for nearly 80 percent of all hired farm labor in the state.

Supply Chains

The contours of the industrial model of agricultural and food production have come into bold relief in the last decades. The pieces fell into place as land, labor, and capital were brought together in a deliberate and coordinated fashion and orchestrated by a small handful of very large and very powerful agribusiness firms. To ensure large quantities of standardized and uniform products, food processors entered into formal contracts with individual farmers. Although there are no systematic data available on contract production, Rick Welsh notes that “since 1960, contracts and vertically integrated operations have accounted for an ever-larger share of total U.S. agricultural production.”15 Today, in the United States, about 85 percent of processed vegetables are grown under contract and 15 percent are produced on large corporate farms. Contract farming allows food processors to exert significant control over their agricultural suppliers. While the processor benefits from these arrangements, the major disadvantage to the farmer is a loss of independence. Many contracts specify quantity, quality, price, and delivery date, and in some instances the processor is completely involved in the management of the farm, including input provision.

Contract farming has also increased farm size. Economies of scale dictate that processors are more inclined to work with large farmers whenever possible. It has been suggested that the processor's ability to award or refuse a contract has contributed to differences in profitability between large and small producers and accelerated the process of farm concentration.16 According to Mark Drabenstott, an economist at the Kansas City Federal Reserve Bank, a more tightly choreographed food system is emerging throughout the country. “The key component in this choreography is a business alliance known as a supply chain. In a supply chain, farmers sign a contract with a major food company to deliver precisely grown farm products on a pre-set schedule.”17

The spread of contract farming is resulting in a reconfiguration of production at the local level, because it is the processor and not the farmer who determines what commodity is produced and where. This requirement imposes a distance limit on producers and leads to narrowly defined supply areas revolving around the location of the processing plants. In the process of this transformation, the ties between farmers and processors have been restructured.

For farmers in the United States and elsewhere, the globalization of the food system means that a much smaller number of producers will articulate with a small number of processors in a highly integrated business alliance. Drabenstott estimates that “40 or fewer chains will control nearly all U.S. pork production in a matter of a few years, and that these chains will engage a mere fraction [italics added] of the 100,000 hog farms now scattered across the nation.”18 In a similar vein, the CEO of Dairy Farms of America (the largest U.S. dairy cooperative), Gary Hanman, recently noted, “We would need only 7,468 farms [out of over 100,000 today] with 1,000 cows if they produced 20,857 pounds of milk which is the average of the top four milk producing states.”19 The consequences are clear: “… supply chains will locate in relatively few rural communities. And with fewer farmers and fewer suppliers where they do locate, the economic impact will be different from the commodity agriculture of the past.”20