Chapter 3

Crossing Over

Let’s return to our question in chapter 1: How do we close the gap between generations to stay connected and relevant?

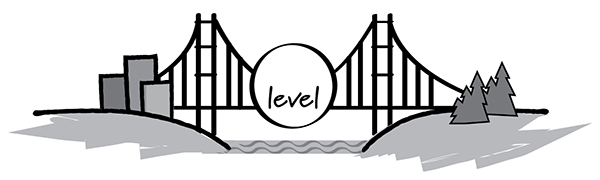

Straight answer: There is no closing the gap. Moore’s Law does not allow it. But, knowing the shortest distance between two points is a straight line, there is still a way to connect with and share relevance between generations. Where we can’t close the gap between the generations, we can build bridges that span the distance between us.

“Okay,” you say. “Makes sense. So, how do we build this bridge between our older and today’s younger generations?”

Here’s how I think we should begin. Let’s follow the example of builders who managed to span one very wide and very dangerous distance by building a bridge. By using their work as a metaphor, we can span the distance between “old” and “new” to bridge the gap between our generations.

One of the best bridge-building examples I’ve found comes from the most famous bridge ever constructed. It’s the world’s most visited, most photographed, and most recognizable span: San Francisco’s Golden Gate Bridge.

When the Golden Gate Bridge opened in 1937, it was the tallest and longest suspension bridge in the world. Boldly painted International Orange, the massive structure stretched out across a one-mile-wide strait called the Golden Gate. Over the frigid cold currents, thick fog, and violent winds that prevail where the San Francisco Bay mixes with the Pacific Ocean, the bridge stands as proof that Where there’s a will, there’s a way. Once considered an impossible vision, the Golden Gate Bridge now offers easy access between the slower, more rural lands to the north and the buzzing hustle of the big city to the south.

For the sake of our bridge-building example, think of the peninsula on the north end of the Golden Gate Bridge, specifically Marin County, like it represents the premillennium generations. This is you, your parents, grandparents, great-grandparents, and so on. There’s a lot of well-earned influence and hard-earned money in Marin County. Many of the people there are proud of their history, their culture, and the area’s unique and extremely high biodiversity. Marin County includes miles of Pacific-swept beaches, rich farmlands, peaceful open spaces, ancient forests, and numerous state parks and natural protected areas.

Today’s young generations are better represented by the buzz of the big city to the south of the bridge. Perhaps you’ve heard of it? San Francisco. A bit different than the neighbors to the north, San Francisco is known worldwide for pushing the progressive edge of almost every political, economic, ecological, religious, and social issue. Sound familiar? It should. That’s exactly what today’s emerging generations are building a reputation on.

As in the time prior to the opening of the Golden Gate Bridge, the distance between our older generation’s place and the youthful side of the gap, way over here, may appear too great a distance to span. Perhaps we also think the gap is too far, difficulties too tough, and logistics too many to make meeting in the middle anything more than wishful thinking. That’s what some people in both Marin County to the north and the city of San Francisco to the south once believed. That is, until a group of brave and brilliant influencers committed themselves to rethinking what it would take to make building the impossible bridge possible.

Now, if you are really interested in the math and engineering needed to join steel, rivets, and massive cables together, you are free to Google search your way through that mass of data on how they constructed the Golden Gate Bridge. We’re leaving those details out of this book. Instead, what we’re going to do is ask and answer three important questions of the bridge-building process that will also help us connect the generations today.

Question 1—Where did they start construction of the bridge?

Question 2—What building materials were used?

Question 3—How did the world know they had successfully bridged the distance between north and south, old and young?

The good news is each of these questions has a very simple and relatable answer we’ll use to rethink how we, too, can bridge the space between our generations.

First question: Where did they start construction of the Golden Gate Bridge? That’s an easy one. On both sides. The first step in building the bridge was to construct both the north and south towers. Each tower stands tall and strong in support of the entire weight of the bridge. It was important that both the northern tower on the Marin County side of the strait and the southern tower closest to San Francisco be completed before any of the suspension cables and surface decking could be added. Similarly, for our young and older generations to successfully span any distance between us, we each need to build support on our own side, from our own side.

It’s far too easy to point a finger across the gap and say something like, “They really should be doing more to reach out to us.” But what good is it to ask the other side to do what this side is not willing to support? That kind of thinking won’t work. What will work is when you start building from your side and they start building from the other. To encourage both groups to work effectively together, I wrote two versions of this book. This edition is for Gen X, Boomers, and Silent Generation readers who want to build something great. The other edition, Becoming the Next Great Generation, I wrote for today’s youth. Each presents the same tools and models needed to prepare us to see the demand of successfully bridging the gap as a challenge and not a threat. Each focuses on a single end: guiding the next generation in gaining access to all they’ll need to become the next GREAT generation. For that to happen effectively, we’ve got to come together and make some important exchanges. So, you start building from your side while they bridge out from the other side, and we’ll soon be meeting in the middle.

Next question: What building materials were used? Once again, the answer is simple. The builders selected proven materials that would stand the test of time. More than simply hours, days, and years, the test of time includes all the physical stressors placed on the bridge. It must withstand everything from natural weathering imposed by the surrounding environment to massive weight from passing loads. The real trick was how engineers joined proven materials together in new ways that allowed those components to perform even better than before. So that’s what we’re going to do too. Throughout the rest of this book, we will be rethinking how to use proven materials in new ways to outperform previous accomplishments.

Build to Celebrate

Finally, what event signaled to the world that the parties had successfully bridged the distance? Again, an easy answer. They met in the middle. Two dates marked the magnitude of this event. The first date was November 18, 1936, when the two center sections of the bridge were joined together halfway between the bridge’s main towers. Workers building from the Marin County side in the north reached out and shook hands with workers building from the San Francisco side in the south. A brief ceremony took place at the center of the span before both sides mixed together in preparation for the next important event: the opening of the bridge.

On May 26, 1937, the longest bridge span in the world opened to the public. That day more than 200,000 people crossed over the gap. Down from the north and up from the south, people met in the middle, mixed together, and moved back and forth over the same space once believed impossible to bridge. Nothing like it had ever been done before.

The only way the two sides were able to meet in the middle is simple: that’s the way they planned it from the beginning. First, those who did the heavy lifting to construct the bridge celebrated their success with handshakes and hugs. Then they invited everyone else to join them in experiencing the benefits of all their hard work. The same is true for us. By building in from both sides, with proven materials joined in new ways that are built to last, we will soon meet in the middle just as we planned from the beginning. By rethinking how bridges are built between us, we can celebrate, share, and experience the benefits of spanning the gap between our generations.

“Okay. We’re ready to start construction . . . from our side, of course. What exactly are we working with here?”

Again, you are asking a great question. For us to get this build right, we’ll need to rethink and prepare for more than just building bridges. In fact, I’m asking for a real paradigm shift in how and what we think about leadership, strengths, and purpose. Call me crazy. I’m okay with that. As I wrote in my Personal Message to Readers in the front of this book, I believe today’s emerging generation possesses more potential to do good in this world than any generation before. But—and this is a big BUT—in order for them to become the kind of change agents who press the world ahead, we must be crazy enough to think different about what will best prepare them to succeed. Today’s “new normal” is truly unprecedented and requires us all to change our age-old ways of thinking about the importance of stewardship, the development of strengths, and the significance of purpose.

CONSIDER THIS:

There are over 20 million more members of Gen Z than their Gen X parents.1

YOUR TURN:

- Who are the young people in your life with whom you want to bridge the generation gap?

- From your perspective, what is the level of difficulty you face in bridging the gap between the generations?

(1 = not difficult; 10 = too difficult to consider)

- List the young people you know who are the most willing to collaborate with you to meet in the middle.