Previous attempts to subdue the British and Portuguese in 1808 and 1809 had shown the complexity of the task that faced the French. A substantial army would be required and was assembled in western Spain. Marshal André Masséna was chosen by the emperor to lead this French ‘Army of Portugal’. Its three corps would be led by General Reynier, Marshal Ney and General Junot, the cavalry reserve by General Montbrun. Its total strength came to some 68,000 officers and men. Other forces, notably an army led by Marshal Soult in southwestern Spain, would provide diversions elsewhere along the border, forcing the Anglo-Portuguese to divide their forces. This powerful army with good, experienced generals, would at last conquer Portugal.

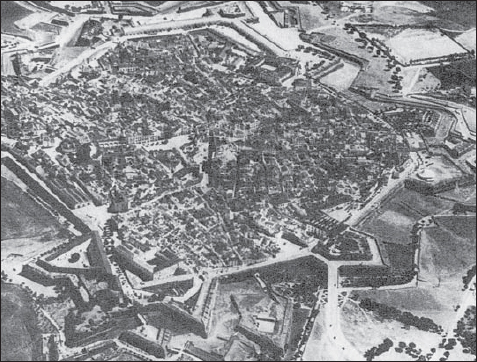

Aerial view of the fortress of Almeida guarding Portugal’s northeastern border with Spain. The southern gate, the ‘Porta da Cruz’ crosses the S. Francisco ravelin to reach the S. Francisco gate into the city. At the left of the picture, the very large western ravelin and gate of S. Antonio. At right, note the heavily casemated Nostra Senora da Brotas ravelin facing east. The remains of the castle are visible at centre left. (Camara Municipal de Almeida)

The French plan disregarded the Spanish, reduced as they were to mere mobs of bandits – these so-called ‘guerrillas’. As events were to prove, the French ignored the Spanish at their peril. As well as troops in western Spain still capable of giving a good account of themselves there remained the armed bands under Don Julian Sanchez, one of the country’s best guerrilla leaders, roaming the plains of Leon. Indeed, the French staging area in western Spain was, at that time, still under the control of the Spanish patriotic forces, in particular the old walled fortress city of Ciudad Rodrigo, only about 30km (18½ miles)east of the Portuguese border. Only once Ciudad Rodrigo was taken could Masséna’s troops prepare to march into Portugal. Masséna’s first objective in Portugal was even more daunting – the great fortress of Almeida. This fortress was the key to the successful invasion of Portugal. Its capture was crucial although a long siege was expected. With Almeida taken, Masséna’s army would then march west, take Coimbra, head south and finally occupy Lisbon. The British and Portuguese Allied army under Wellington would ideally be crushed along the way or at least forced to evacuate Portugal. The Allied army – especially its Portuguese component – was considered incapable of confronting a strong and well-equipped French army. This was Napoleon’s and Masséna’s dream scenario.

Since January 1810 a much more sombre scenario had ‘occupied the most serious consideration’ of government ministers in Britain: the measures to take should the Anglo-Portuguese army be defeated by the French. In the ‘event of the necessary evacuation of Portugal by the British forces’, Wellington was asked to take the British army to Cadiz, in Spain. The Portuguese army might be convoyed ‘to the Brazils’ or to ‘some other part of the Peninsula’. It was hoped that a few toeholds could be retained in Portugal ‘during the remainder of the war’. The seacoast fortress of Peniche was to be kept in ‘permanent possession’ by the British forces as well as the fort of Bugio at the entrance of the Tagus River ‘and perhaps one of the islands off Faro’.1

While acknowledging the cabinet’s concerns, Wellington and the whole Allied army felt that Portugal could be defended successfully. Wellington was a fine geostrategist who clearly saw the fundamental conditions necessary to military success in the Peninsula. He was convinced the French could be beaten in Portugal and indeed in the whole Peninsula, but only if certain basic conditions were met:

First, it was vital that a first-class and numerous Portuguese army served alongside the British. Secondly, control must be retained of the two key fortresses of Elvas and Almeida. Finally, Portugal must be totally secured before the Anglo-Portuguese armies could carry the war into Spain.

It was the maintaining of a strong and efficient Portuguese army that was perhaps the most perplexing to the government in Britain. The cost of 10,000, then 20,000 men was assumed by Britain from late 1808. Many British officers had already been seconded to the Portuguese army but, as Wellington reported, it was not enough. The British ‘Portuguese Subsidy’ had grown to nearly £1,000,000 in 1810. Wellington knew this was too little and now put the actual cost of a 30,000-man Portuguese army at over £1,600,000 – the equivalent of around one billion pounds Sterling today – a stupendous amount. And this was ‘exclusive of clothing and arms which are to be furnished by Great Britain’ at further expense. The House of Lords had questioned the subsidy in late 1809, some Lords considering the maintenance of a British army in Portugal against Napoleon’s troops as hopeless. However, Wellington’s 30,000-man subsidy was approved in April 1810 and raised to £2,000,000 in 1811. In all this, it should not be forgotten that Portugal had to somehow find the money for the balance of its forces, another 13,000 regulars in March 1810, plus garrison and auxiliary forces, a near-crippling expense for a country ruined by war. Britain could certainly bear the cost but the expenses of the conflict were nevertheless huge. Besides the Portuguese subsidy there was the expense of maintaining the British troops themselves, perhaps another £2,000,000 and other expenses such as those associated with the naval forces in that area.2

Aerial view from the northwest of Elvas, the fortress guarding the southeastern border with Spain. The top left of the picture faces east towards Spain. From an old photo. (Camara Municipal de Elvas)

Wellington with his British and Portuguese generals braced themselves for the onslaught from the end of 1809, convinced that Napoleon would try to invade Portugal for a third time. In an attempt to force a conclusion, the French were expected to commit a very large force. Such an invasion was unlikely to come from northwestern Spain along the route used by Soult in his attack on Porto in early 1809 nor along the route of Junot’s 1807 invasion which would now be heavily defended by thousands of determined troops. The only alternatives were the two traditional invasion routes: the southern via Elvas or the northern via Almeida. The southern route seemed less likely as there were still sizeable Spanish and British forces in Cadiz and southern Andalucia and it would take time to move a huge army along this route and create major logistical problems. Wellington reasoned that Masséna would come via Almeida and it was this route Napoleon chose in his orders to his Marshal.

While the northern invasion route via Almeida appeared the most likely to the Anglo-Portuguese staff, the French were putting up various feints to keep their enemies guessing so as to divide their troops and thus weaken their defences. The Anglo-Portuguese, with fewer troops than the French, knew they could only have a sizeable force in one area. Communications and intelligence were therefore all-important to Wellington and his generals. The Portuguese component of Wellington’s army included a ‘Corps of Mounted Guides’, which was an intelligence-gathering unit. Wellington also had the services of a Portuguese innovation – a ‘Telegraph Corps’ for transmitting information rapidly. Supervised by the Portuguese Royal Corps of Engineers, this unique unit manned small stations on hills so that information could be transmitted from Almeida to Lisbon in a matter of hours and from Elvas to Lisbon in a matter of minutes. It should be noted that the French had nothing like the intelligence and communication system that the Anglo-Portuguese had set up. Furthermore, Spanish guerrillas, especially those under Don Julian Sanchez operating in western Spain, provided much valuable information to Wellington on French troop movements.

Once the northern invasion route was confirmed, that is where Wellington would deploy his army. He would not, however, risk his troops in an advance into Spain. It would have been very tempting to try to relieve the siege of Ciudad Rodrigo, but on the flat plains of Leon, Wellington’s Anglo-Portuguese would have probably been overwhelmed by Masséna’s stronger force, especially well provided with numerous and experienced cavalry and artillery units. The better course was to remain in mountainous Portugal where high ground could be used to stall and inflict losses on the invading enemy. In such terrain, Masséna’s cavalry and artillery would be much less effective in a general engagement.

The ideal Anglo-Portuguese scenario was for Masséna to lay siege to the fortress of Almeida, which would hold out for months and, hopefully, that the French would fail to take it. Wellington’s force would be nearby to shadow Masséna’s every move and harass the French besiegers, finally forcing them to abandon the siege and return to Spain.

If Almeida fell, however, Britain and Portugal’s only sizeable field army simply could not be risked in an ‘all or nothing’ battle. The plan was to inflict casualties during a fighting retreat towards Lisbon. On the other hand, Lisbon had to be defended at all cost. Masséna and Wellington both knew if that city was taken, it would mark the effective end of the British intervention in the Peninsula and its total occupation by the French. To prevent this, in late 1809 the Portuguese and British secretly started building numerous defence works north of Lisbon which spanned the wide peninsula between the Tagus River and the Atlantic Ocean. These works became famous as the Lines of Torres Vedras. They would constitute the last line of defence in Portugal.

It was clear in 1810 that despite the efforts of both Wellington and the Portuguese, Portugal was far from secure and had to be defended at all cost. If this defence was effective and the invaders driven out then the war could indeed be carried into Spain.

1 These considerations were discussed at length and it is obvious that the British Cabinet was very worried despite Wellington’s confidence. PRO, WO 6/34 and Dispatches, VI.

2 On the Portuguese subsidy, see in particular PRO, FO 63/120, WO 1/244 and Supplementary Dispatches, VII, pp. 593–594.