Wellington kept his army some distance west of the River Coa. This gave him the flexibility to move in any direction quickly without being trapped with his back to the river. It also ensured that Masséna could not attack him by surprise but, on the contrary, the Anglo-Portuguese army could threaten the French army’s flank while it besieged Almeida. Not a great threat however, reasoned Masséna, as Wellington also could not cross the Coa without difficulty.

French dragoon, c. 1805–11. The bulk of Masséna’s cavalry consisted of squadrons of dragoons detached from a variety of regiments. (Print after Meissonnier)

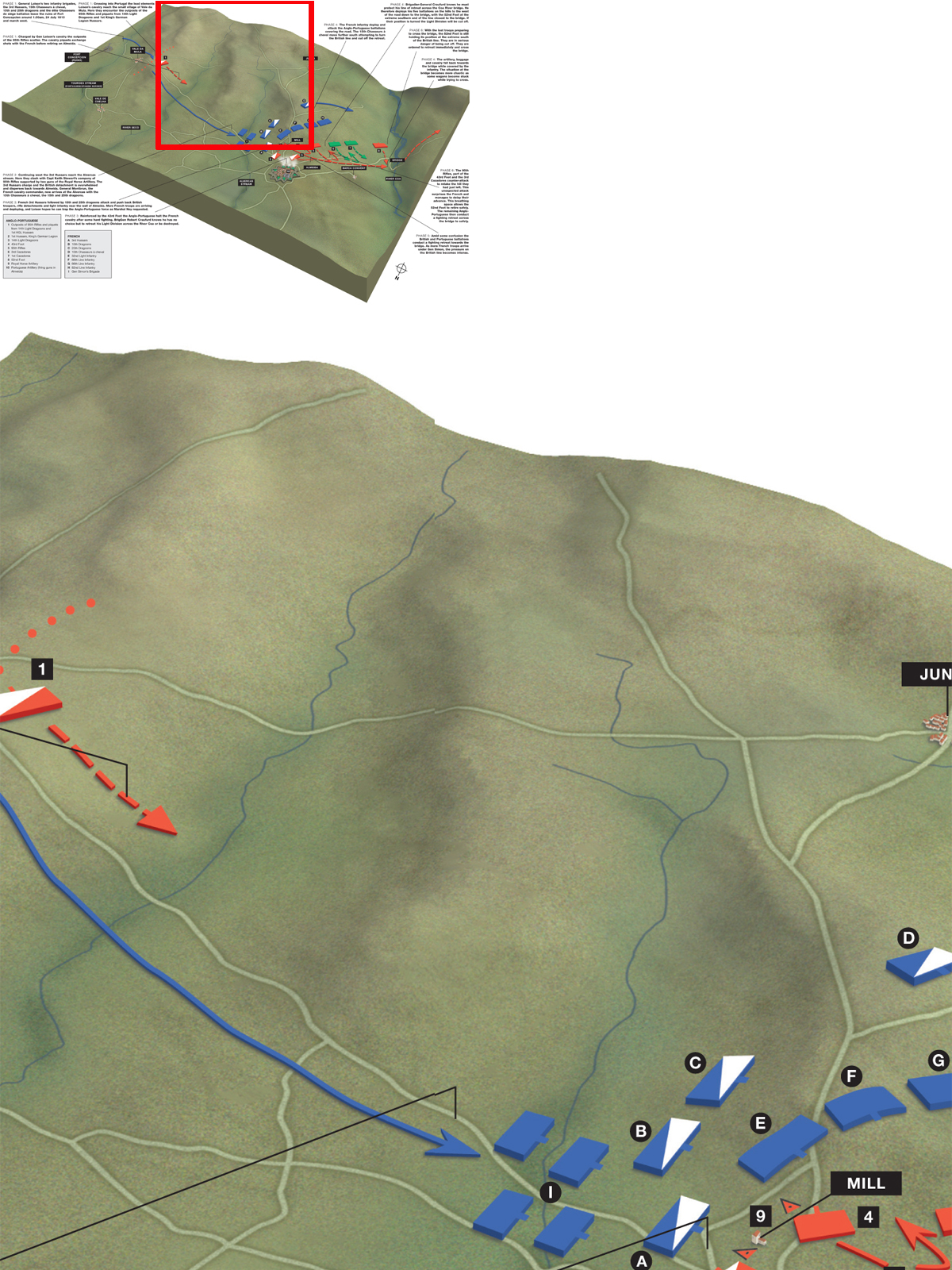

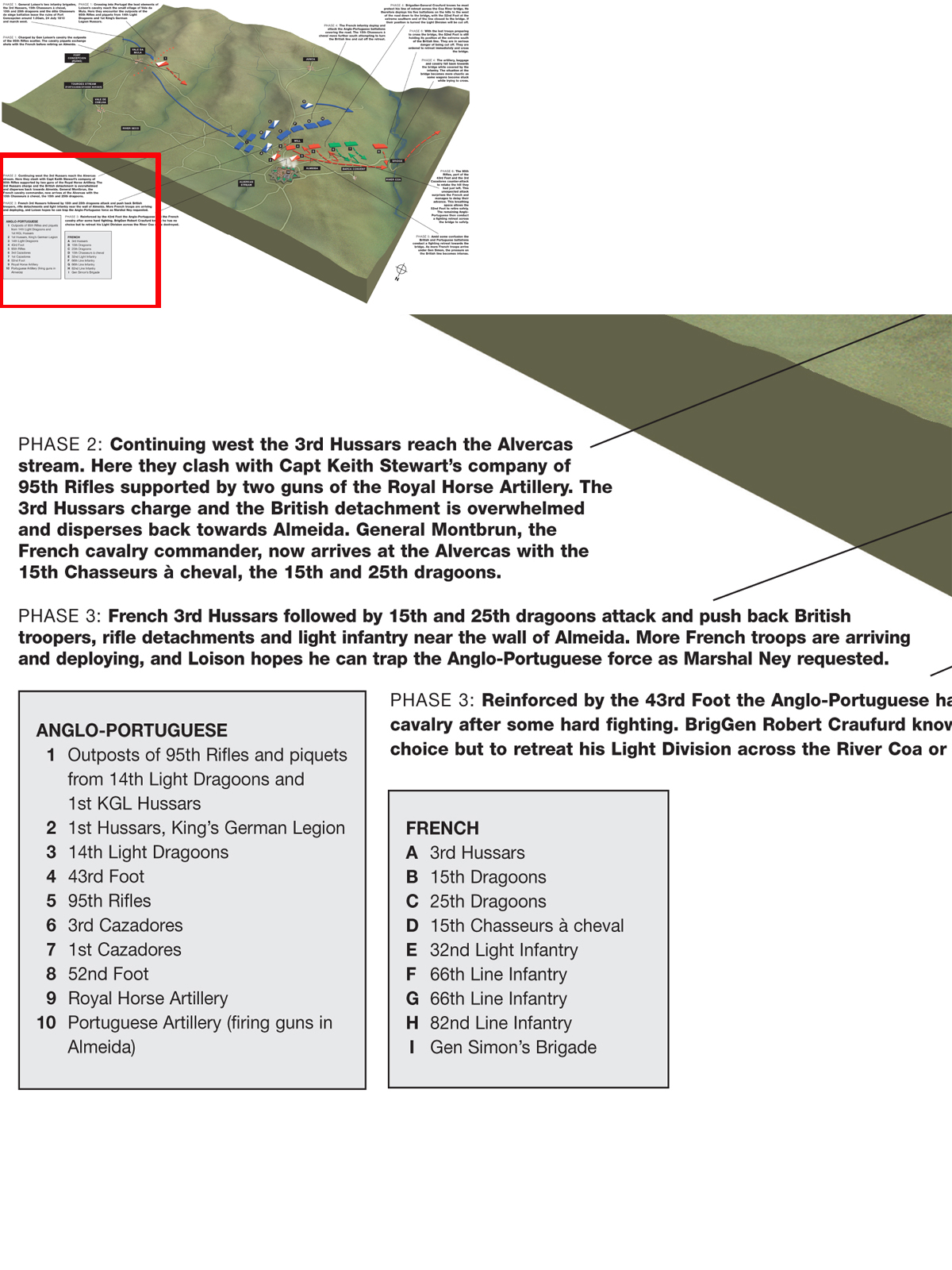

After the fall of Ciudad Rodrigo, Masséna’s army tarried there for a time as it lacked supplies and transport bullocks and needed to organise for the next stage of the campaign: entering Portugal and besieging Almeida. Wellington, for his part, had deployed MajGen Robert Craufurd’s Light Division on the Spanish border to keep tabs on Masséna’s movements. Craufurd’s force consisted of the 43rd and 52nd light infantry regiments, the 95th Rifles, the 1st and 3rd Portuguese Cazadores battalions, the 14th and 16th light dragoons, the 1st Hussars of the King’s German Legion and Ross’s Troop of the Royal Horse Artillery, in all a force of about 4,000 men. They were posted just south of Almeida, forming a rough line between the fortress and the village of Juncas about 4km (2 miles) to the south. Craufurd had his back to the Coa River and, in case of retreat, could use only the single bridge nearby, about 2km (1 mile) to the west. His forward elements spent some time skirmishing with French outriders but, on 21 July, the whole situation changed dramatically.

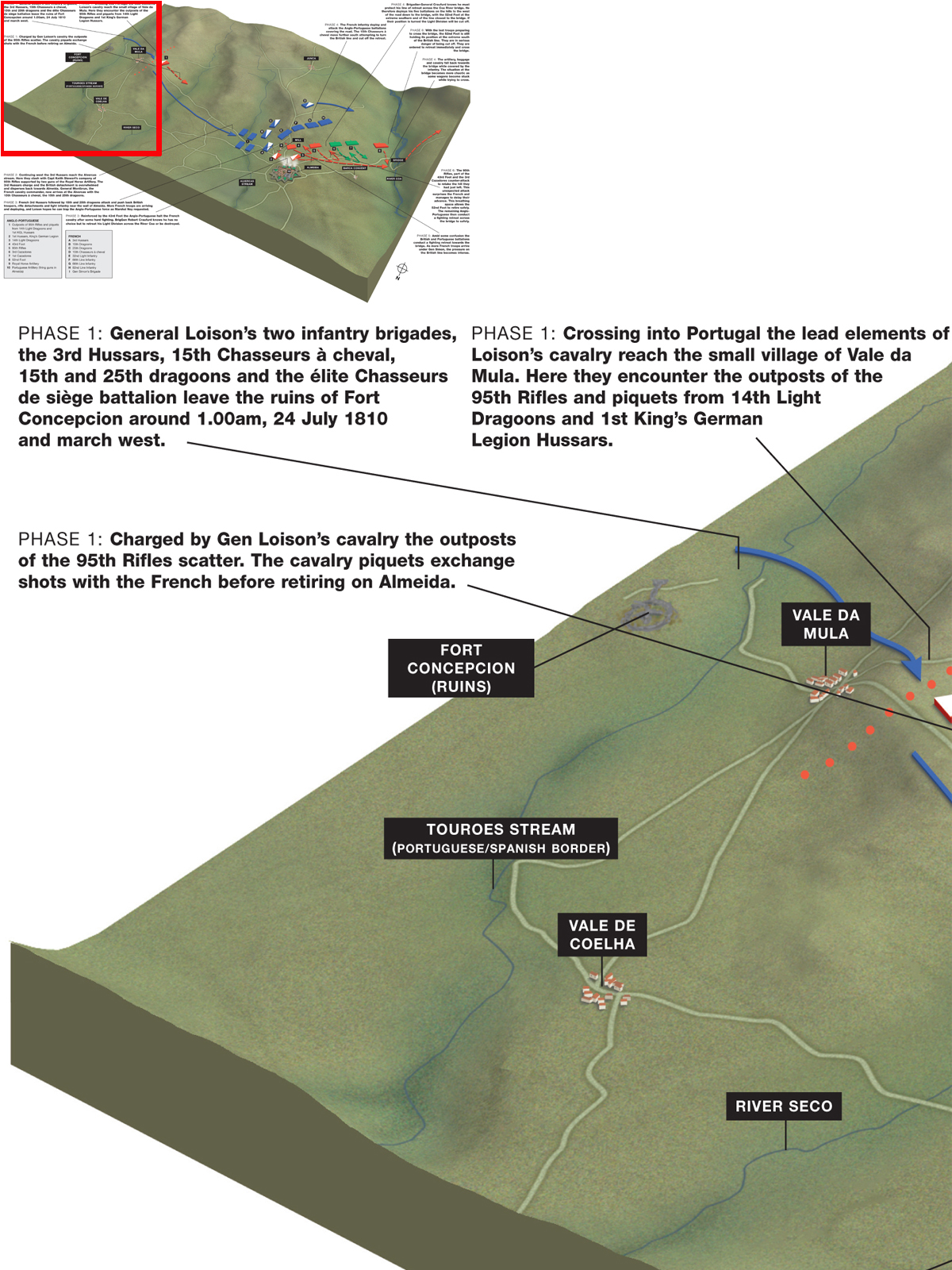

On Masséna’s instruction, Marshal Ney with his whole 6th Corps was rapidly moving west towards Portugal. The two cavalry brigades, Gardanne’s 15th and 25th dragoons and Lamotte’s 3rd Hussars and 15th Chasseurs à cheval totalling about 3,000 troopers rode in front. The fast-moving Chasseurs de siège light infantry battalion was with the cavalry. Then came Loison’s 3rd Infantry Division of some 6,800 men in 13 battalions formed in columns. These were the forward elements and they were marching rapidly towards the Portuguese border. In all a force of nearly 10,000 men.

Craufurd was thus heavily outnumbered although he did not realise it at first. Additional troops of Ney’s 6th Corps followed Loison. Further back was Mermet’s 2nd Infantry Division with another 11 battalions. And behind those another eight battalions of Marchand’s 1st Infantry Division with the 10th Dragoons, although it was very unlikely these units would be engaged. Marshal Ney knew that the Anglo-Portuguese would retreat; his one hope was that they would delay so that Loison might catch up with them. If so, Ney wished that his troops first cut off the Anglo-Portuguese Light Division from Almeida and, secondly, that they block the Light Division’s retreat across the River Coa.

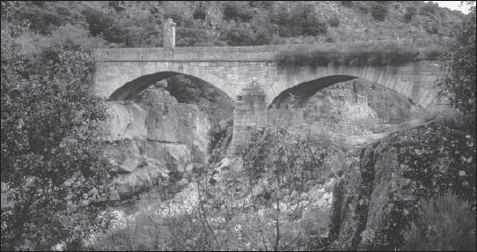

The road leading to the bridge over the River Coa seen from the east. (Photo: RC)

Loison arrived at the ruins of the Spanish fort La Concepcion, regrouped his forward troops and prepared to move against the nearby Allied corps. The night of 23 July was disturbed by an unusually fierce thunderstorm But at 1.00am on 24 July, the French marched on in the rain and wind and thunderbolts, reaching Dos Casas some hours later where they formed columns. By then, the storm had subsided and it was early dawn. At 6.00am the columns moved west. The 3rd Hussars and 15th Chasseurs à cheval were in front followed by the Chasseurs de siège elite battalion, the 15th and 25th Dragoons and, last but not least, Loison’s two infantry brigades. The cavalry was first to cross into Portugal and troopers of the 3rd Hussars reached the small village of Vale da Mula followed by the Chasseurs de siège.

The forward elements of the French cavalry and chasseurs encountered the outposts of the 95th Rifles, which they scattered, and engaged the British cavalry troopers of the 14th Light Dragoons and the 1st King’s German Legion Hussars out on forward pickets. The British cavalrymen had seen parties of French cavalry scouts before, but this time it was different. More and more French kept coming. Before long, instead of random pot shots, Craufurd and his men could hear sustained carbine fire to the east. Shortly thereafter the overwhelmed British troopers and riflemen were beating a retreat towards Almeida – something was wrong.

Colonel Laferrière of the 3rd Hussars led his troopers west along the road; they met no opposition until they neared the banks of the small Alvercas River. There, a company of the 95th Rifles under Capt Keith Stewart with two guns of the Royal Horse Artillery opened fire. However, the British detachment proved unable to resist the seasoned troopers of the 3rd Hussars. The Hussars’ first charge overwhelmed them and they scattered and ran back towards Almeida. General Montbrun, the cavalry commander, now arrived at the Alvercas river bank with the 15th Chasseurs à cheval and the 15th and 25th Dragoons. French horse artillery was also arriving, followed by the two infantry brigades of generals Ferey and Simon. Montbrun secured the position on the Alvercas River and paused for the troops to regroup. He then deployed to attack further west and marched on. Simon’s infantry brigade was to the north, to its south and somewhat further forward were the 3rd Hussars and 15th Dragoons, then Ferey’s brigade with the 15th Chasseurs à cheval and the 25th Dragoons behind. It was a full-scale attack by a French division and they were only about a kilometre from Almeida. Worse, they might cut off Craufurd’s Anglo-Portuguese Light Division.

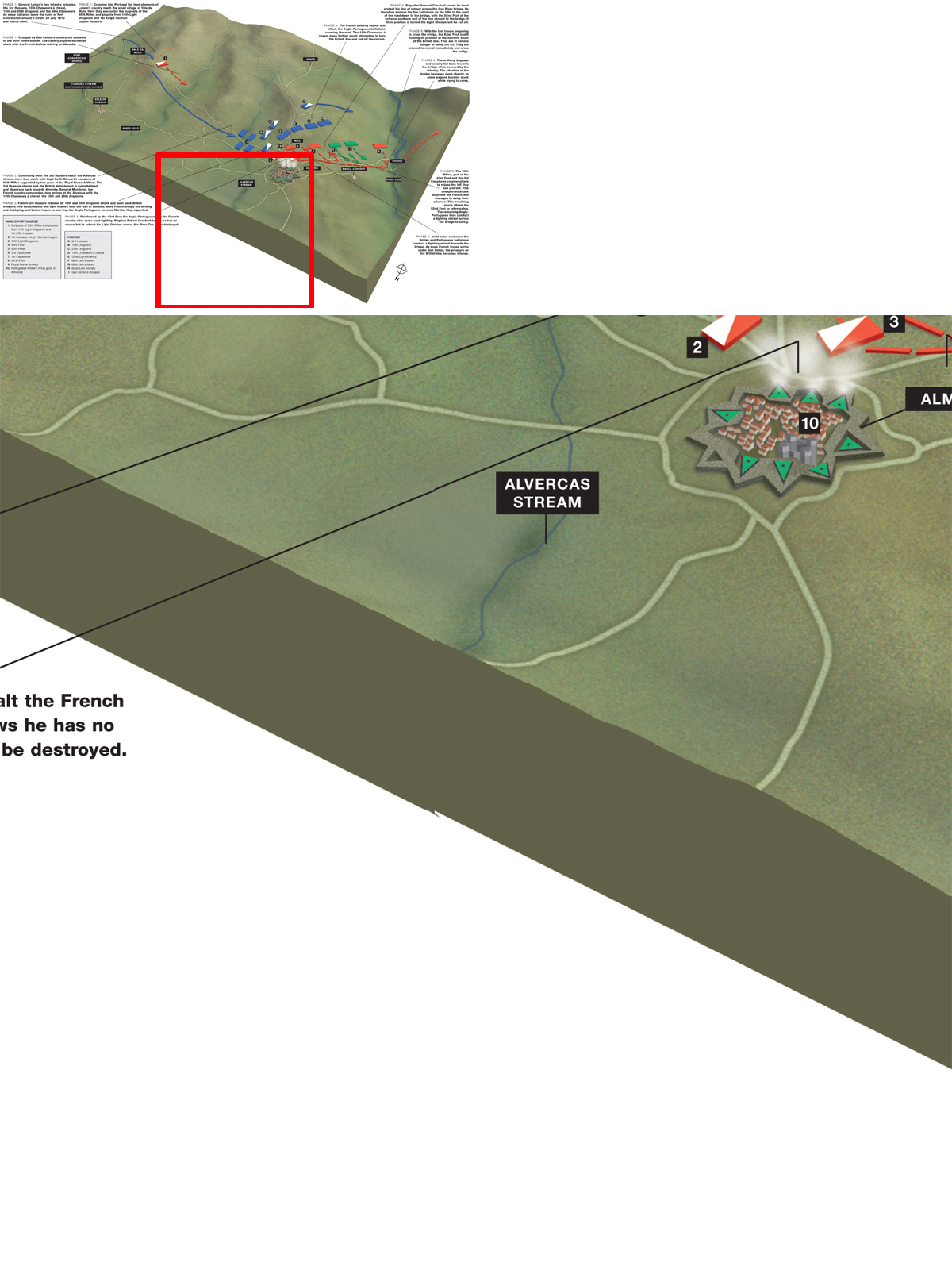

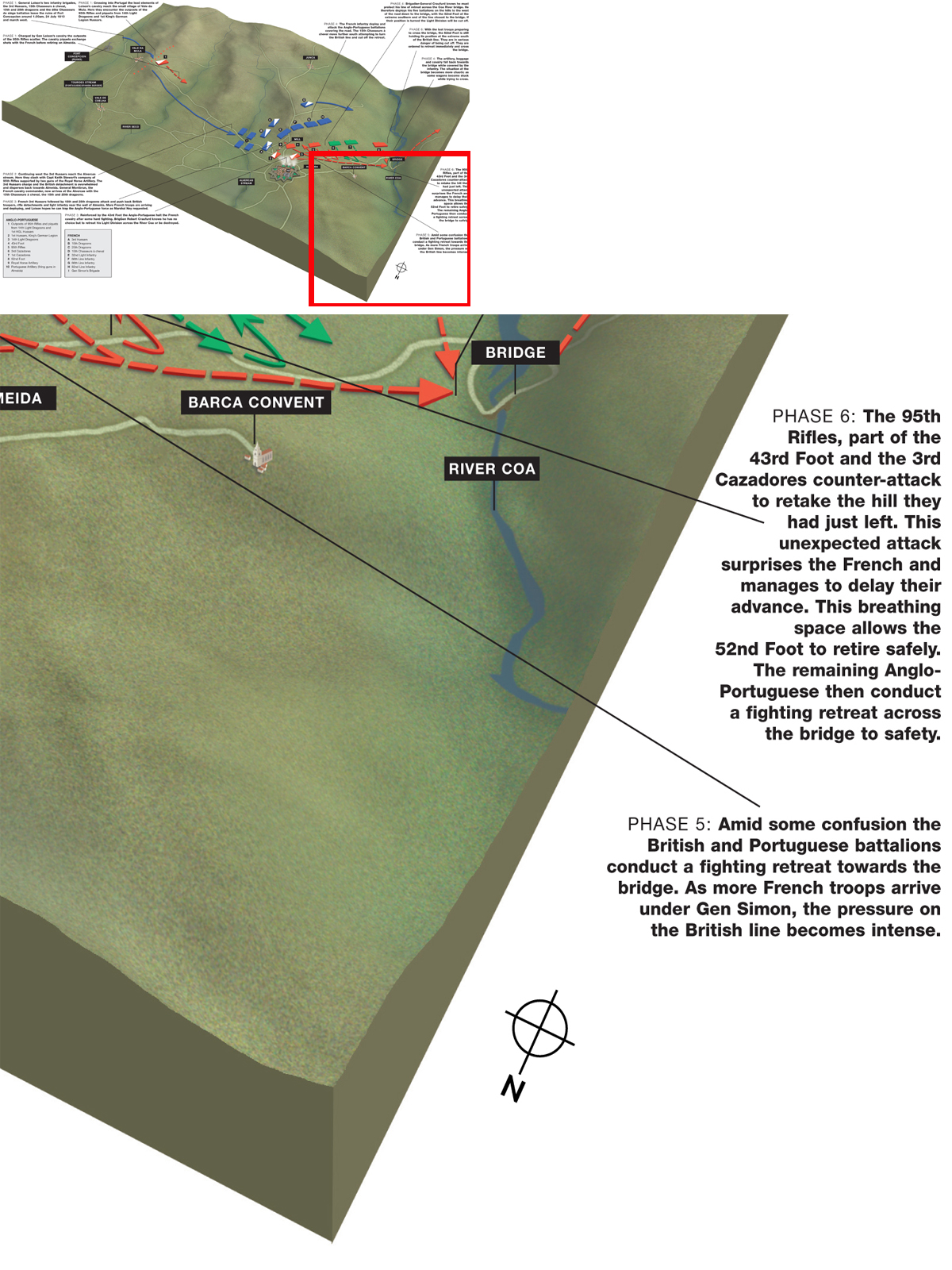

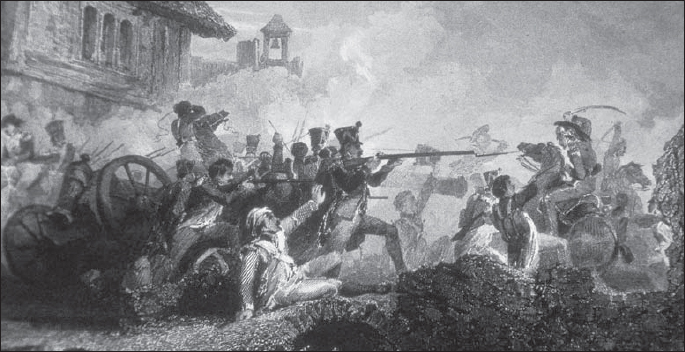

24 July 1810, viewed from the north-west showing the desperate fighting as Brigadier-General Robert Craufurd’s Light Division conducts a fighting retreat across the River Coa under mounting pressure from elements of Marshal Ney’s 6th Corps.

The ‘windmills’ near Almeida were most likely small depots for fertiliser which the Portuguese nicknamed ‘Pombal’ after their famous 18th-century prime minister. The one shown is just south of Almeida and the fortress’s works can be seen in the background. This Pombal or one or more like it were in this same area where Craufurd’s Light Division made contact with Marshal Ney’s pursuing French troops. (Photo: RC)

The French, seasoned campaigners that they were, had moved expertly and rapidly. For all his qualities, ‘Black Bob’ Craufurd was nearly caught as his Allied soldiers were now surprised to see the fields to the east covered with lines of French infantry. With drums beating, supported by squadrons of cavalry and with scores of skirmishers to their front, all these French troops were moving towards them.

Part of the company of the 95th Rifles, which ran back from the Alvercas River, had now regrouped around a ‘mill’ – probably actually a Pombal – held by half a company of the 52nd Light Infantry with a couple of field pieces and two other guns of the Horse Artillery nearby for support. Another company of the 95th, O’Hare’s, was ordered forward to check the French and took position behind a stone wall south of the mill. They opened fire on a column of the 32nd French Line Infantry but were now under fire themselves from cannon of the French horse artillery. The voltigeurs of the French 32nd came right up to the wall and charged in. They had a distinct advantage in close combat wielding the long Charleville muskets with fixed bayonets against riflemen with their shorter Baker rifles fixed with the awkward sword-bayonets. The British riflemen soon gave way and fled.

Meanwhile, drums were beating and bugle calls sounded in the Anglo-Portuguese camp. In Almeida’s bastions, the gunners prepared their cannon while Craufurd’s troops outside its walls formed for battle. The Light Division was deployed in a line just east of the road running southwest from the fortress of Almeida to the stone bridge on the River Coa. The 1st King’s German Legion Hussars were nearest Almeida, then the 14th Light Dragoons behind the 43rd Light Infantry near a ‘windmill’, then the 95th Rifles, the 1st Cazadores, the 3rd Cazadores and the 52nd Light Infantry closest to the river.

The guns on the southern bastions of Almeida opened up on the ‘French’ running past below but the men in dark uniforms turned out to be riflemen of O’Hare’s company of the 95th – a few seem to have been injured before the gunners realised their error. Lieutenant Johnson’s detachment of the 95th retreating at the far north of the British line was caught and outflanked by die 3rd French Hussars, who galloped into them slashing with their sabres. And worse was to come as the French 15th and 25th Dragoons moved up in support. Fortunately for the riflemen, some of the British 43rd came up to support them which stopped die French cavalry but only after some hard fighting. Only one officer and 11 men of O’Hare’s 95th company escaped unscathed.

Capt William F.P. Napier (1785–1880) served in the 43rd Light Infantry and was shot through the left hip at the River Coa on 24 August 1810. Although wounded, he nevertheless was with his regiment at Bussaco. He wrote the first detailed British history of the Peninsular War and was later Knighted. He is shown in the uniform of an officer of the 43rd c. 1810 – scarlet faced with white, silver buttons and epaulettes; a. pelisse slung over the shoulder indicates he is a light infantry officer. The medals were added later.

The 15th Chasseurs à cheval and more French infantry were arriving on the scene but it took about two hours for the superior French force to deploy for the attack on the Light Division, At this point Craufurd Committed a near fatal error; instead of falling back lo the other side of the River Coa as fast as he could, he held his line. This was against Wellington’s ‘most positive’ instructions not to engage the French on the cast side of the Coa. His division of about 4,000 men – 2,000 British, 1,200 Portuguese and about 800 light cavalry – was strung out on a front of about three kilometres. Fortunately for him, only part of Ney’s 6th Corps, some 6,000 men – 3,700 infantry and 2.300 cavalry – was about IO HI lark, lint Craufurd was ultimately doomed even if he managed to hold his position as, eventually, more of Loison’s Division would arrive and, finally. Marshal Ney with the rest of his corps.

While Ferey’s French brigade was forming into four columns to attack the British 43rd near its ‘windmill’, the 15th Chasseurs à cheval were riding south to outflank the 52nd at the other end of the British line. Ferey’s columns, made up of the 32nd light and the 66th and 82nd Line infantry, marched past Almeida against die left flank of the British position. The fortress’s guns fired on the French columns as did the 43rd, but the French did not return the fire. The cannon fire from Almeida ‘became extremely hot, fun was badly aimed’ according to the French report of the battle As they closed the French charged the British with fixed bayonets. The pressure from the French was now mounting and. in spite of suffering casualties, the French columns were driving a wedge between Almeida and the British 43rd Foot to the south. The 3rd Hussars also charged, fell on the British infantry and sabred many men – Ney’s instructions to isolate the fortress from the Allied force outside were being carried out.

Drummers of a French Infantry Regiment, c. 1805–10. (Print after Raffet)

The French charges, while successful, were hampered by ‘a terrain so difficult thai most of our cavalry found, it impossible to join in the action’. Marshal Ney later reported that the British cavalry ‘refused to charge’ the French, rallied under the protection of Almeida’s guns and hurried to cross the Coa River. In fairness to the British and German troopers, to charge the French would have been tantamount suicide under the circumstances and retreat was the sensible option.

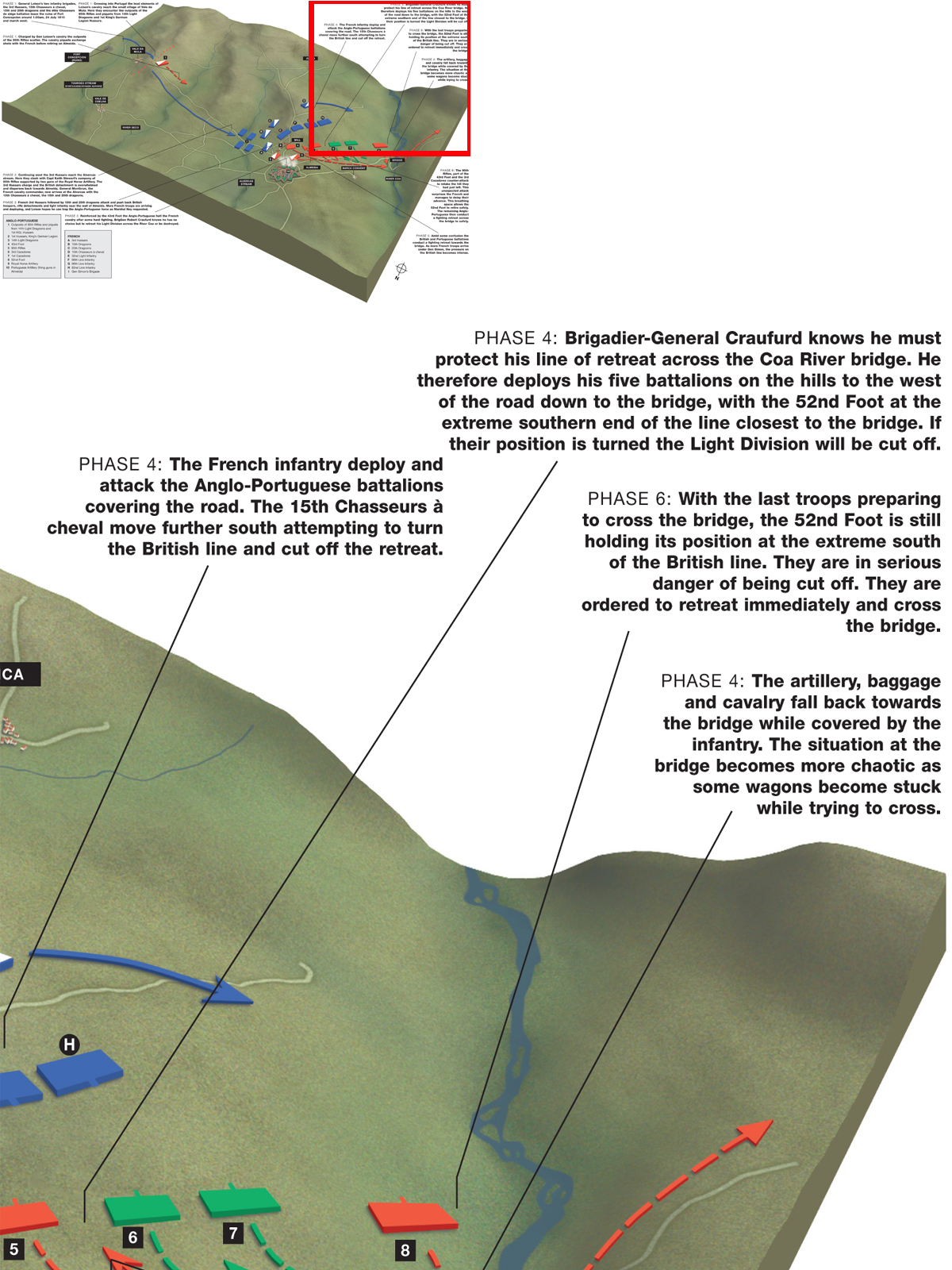

The Light Division was confronted with the prospect of being cut off from its only line of retreat, the stone bridge on the River Coa. Craufurd now realised his force had to cross the river, and cross it quickly. However, the infantry would have to hold the French back as long as possible to enable the supply wagons and the guns of the horse artillery to cross the bridge first, followed by the rest of the troops. The British 52nd and 43rd Foot and the companies of the 95th Rifles would have to bear the brunt of the French columns’ attacks. The 1st and 3rd Cazadores were to hold their position at the centre to cover the road down to the bridge. The 52nd Foot was on the far right of the British line and was to avoid being outflanked at all cost – if it broke, part of the British force’s retreat would inevitably be cut off.

At the Coa River on 24 July 1810 Craufurd and his Light Division were very nearly caught napping by Marshal Ney’s 6th French Corps. Craufurd miscalculated the strength and the swiftness of the French attack and his men had to fight hard to extricate themselves from a difficult situation. The Coa River bridge was their only means of escape and had to be held at all costs. The scene shown is in the latter stages of the battle when the Light Division had succesfully retired across the bridge and French attempts to cross were beaten back. (Patrice Courcelle)

The bridge on the River Coa looking towards the north. The original bridge was damaged during the French invasions and repaired later. The stone tablet rising at its centre has commemorative inscriptions. (Photo: RC)

The British retreat soon ran into problems when a wagon missed the sharp turn before the bridge and blocked part of the road. The result was a ‘traffic jam’ at the worst possible moment. The bridge and its immediate area was soon crowded with vehicles and men trying to get across. While this was happening, the French redoubled their attacks with the Chasseurs de siège, the 32nd Light Infantry and the 66th and 82nd Line infantry gradually gaining ground on the British 43rd and 95th Rifles. Colonel Sydney Beckwith of the 52nd, in charge of that sector, ordered the 1st and 3rd Cazadores to fall back. This went smoothly for the 3rd Cazadores, who took up position on the ridge overlooking the Coa River allowing them to cover the road, but it was less successful for the 1st Cazadores. Some companies redeployed but others were seen to rush down towards the bridge to cross it. This created the impression that they had broken and were running for it. In fact, as the subsequent inquiry into the battle revealed, the Cazadores had not been given clear instructions by Beckwith and believed it was their turn to cross. Whatever the cause, the British situation was rapidly becoming confused and desperate.

Although the British and Portuguese put up stiff resistance, the French were stronger and Craufurd ordered most of his infantry to withdraw. The retreat was carried out in some confusion as the French infantry were close on their heels and the French cavalrymen of the 15th Chasseurs à cheval joined in the pursuit. Allied company commanders tried to withdraw as best as they could down the hill and across the bridge. Craufurd ordered part of the 43rd, the 95th Rifles and the 3rd Cazadores to hold the height overlooking the bridge while others retreated. Not an easy task under mounting French pressure. The Allied screen was gradually falling back from the hills to cross the Coa when it was realised that the 52nd had not crossed and was still deployed further south. The French were already moving onto the heights that the British and Portuguese soldiers had just left overlooking the bridge, and would soon cut off the 52nd. Major George Napier rode off at once to tell the 52nd to retire immediately on the bridge. Beckwith realised that the French had to somehow be cleared off the heights above the bridge to gain a little time. He ordered the 95th to retake the hill they had just left. Part of the 43rd and the 3rd Cazadores also supported them, a move that so surprised the French that they were stopped long enough for the 52nd to cross, after which the remaining British and Portuguese companies also fell back across the Coa.

Trooper of the 4th French Dragoons and a grenadier of the 94th French Line infantry, c. 1810–11. Two squadrons of the 4th Dragoons were with Masséna’s army. The 94th was part of Marshal Victor’s 1st Corps in Spain but the dress of the infantry with Masséna would have been generally the same as shown in this English print by Goddard and Booth. Foot troops wore blue uniforms with shakos, dragoons and Chasseurs à cheval green and hussars a wide variety of colours. The grenadier is shown with a bicorn, which was worn when the bearskin cap or shako was not required.

Craufurd’s Light Division had been mauled but survived. If Marshal Ney’s orders had been followed to the letter, Montbrun’s cavalry brigade would have attacked the Allies’ right (or south) flank and cut off the retreat.

Commenting on this first battle of France’s third invasion of Portugal, Oman’s history severely chastised Masséna for falsifying reports of this engagement which ultimately appeared in the French official Moniteur as a glorious affair for the French army with a colour and guns captured. However, more recent research into Masséna’s papers by Professor Donald Howard shows that the reports were not falsified by the marshal but by the editors of the Moniteur as it was, first and foremost, a propaganda paper totally controlled by the French imperial government. Oman also criticised the report of the captured British colour as totally unfounded. He wrote that Ney never mentioned ‘the imaginary flag’ that Masséna reported captured. Ney did in fact mention it in his dispatch of 29 July to Masséna stating that it was captured on 24 July by a M. Domel, a drummer in the 25th Light Infantry. So there seems little doubt that some sort of colour was captured, even if only an ordinary Union Jack from an outpost. As the 95th and the Cazadores had no colours, it may have belonged to the 43rd or 52nd Foot, unless a cavalry standard of the 1st King’s German Legion Hussars or the 16th Light Dragoons was taken. The identity of the unit from which the colour was captured is not given. Ney’s report of the Anglo-Portuguese strength as given in the Moniteur spoke of 10,000 men including 2,000 cavalry and has been used in many French histories since. Yet, in his letter to Masséna written at two in the afternoon of the 24th, he mentioned Craufurd’s (which he spelt ‘Crawfurd’) force as 2,000 cavalry and 3,000 infantry, so it seems the editors of the Moniteur ‘polished’ Ney’s dispatches too. Craufurd actually had about 4,000 men. British exaggeration was even more pronounced. Craufurd’s letter in The Times refuted the Moniteur’s version of events but went on to state that he had, in effect, fought Ney’s whole 6th Corps of 24,000 men. This figure has been followed by Napier, Oman and other historians until recently. Yet it was only a relatively small part of Ney’s 6th Corps that was engaged at the Coa – Ferrey’s 3,774 infantrymen and Montbrun’s 2,279 troopers. The main body of the 6th Corps was much further back.

French infantry clash with Allied cavalry during the Bussaco campaign. (Print after J. Gilbert)

The casualties reports also varied. Ney mentioned 530 French casualties killed or wounded. In his 24 July dispatch he stated that the British casualties were ‘rather considerable’ and that he ‘already’ had by that time (2.00pm) about 100 prisoners including ‘a few officers’ held at his HQ. The British reported losses of 36 killed, 273 wounded and 83 missing but, after the battle, the French found the bodies of 301 British and Portuguese soldiers. Loison, who supervised the post-battle mopping up, estimated about 500 Allied wounded and about 100 Allied troops made prisoners. The later inflated French report of 60 Allied officers and 1,200 men killed and wounded was of course for propaganda purposes.

The French were pleased with their success. The faults and virtues of Craufurd’s command of the Light Division in this engagement were debated at the time and by historians since. Wellington, however, was the one who had the ultimate responsibility. In a private letter to his brother William Wellesley-Pole, he confided that he ‘had positively forbidden the foolish affair in which Craufurd involved his outposts’ as he did not want the Light Division in battle on the east side of the Coa River. But an engagement there was and Wellington thought that Craufurd should not have remained ‘two hours on his ground after the enemy had appeared’ but crossed the river at once to safety – certainly the most sensible response in the circumstances. Yet he did not condemn Craufurd, who was still his best light troops commander, but defended him: ‘if I am to be hanged for it, I cannot accuse a man I believe has meant well, and whose error is one of judgement and not of intention’.

In any event the Allies had learned two important lessons. The first was that Craufurd’s troops, in spite of the errors of some of their officers, had proved remarkably resilient and that the untried Portuguese Cazadores had performed very well. The second was that the French imperial army, for all its supposed defects, was a well-led, brave and fast-moving force and that anyone who ‘fooled around’ for too long with the likes of Marshal Ney would be lucky to live to regret it.