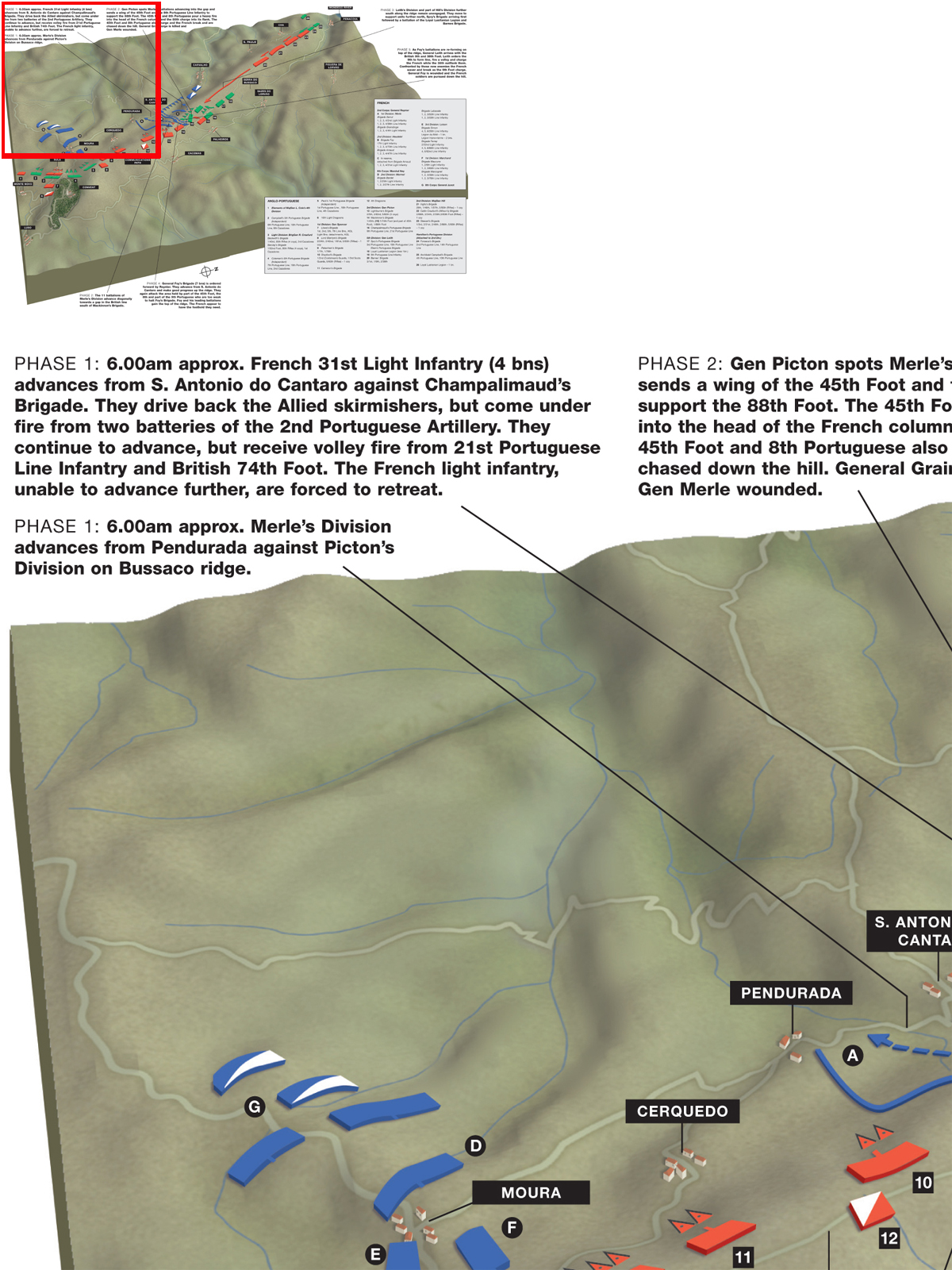

Dawn at Bussaco on 27 September was typically foggy. Reynier’s 2nd Corps was already up, formed, and ready to march. As the day’s early light became stronger, the brigades marched out towards their objective – a lower spot on the ridge. Light infantry voltigeurs and chasseurs formed the skirmish screen and advanced. They were followed by Heudelet’s Division formed into an 8,000-man column of 15 battalions to the left (or south) and Merle’s Division of 6,500 men in 11 battalions also in column to the right. As they advanced, the order of the columns became disrupted over the increasingly rough terrain with Merle’s Division moving ahead. The further up they climbed, the more irregular the formations became until they were broken up into numerous large groups of soldiers struggling to climb the increasingly steep hill. The frontage of both columns had been compressed and they had veered to the left as they climbed towards the ridge.

The firing began as the French and British skirmish screens clashed. The British skirmishers were the light companies of the 45th, 74th and 88th Foot. This thin line of British troops was driven up towards its main body by the much stronger French skirmish line. Up on the crest of the ridge, the officers and men of Picton’s Division heard the shooting, but looking down could see nothing of the climbing French multitude because of the fog. It was clear to General Picton that something was happening and he sent a wing of the 45th Foot and the 8th Portuguese Regiment to cover the area between him and the 88th Foot. Allied army skirmishers of Champalimaud’s 9th and 21st Portuguese regiments were also now being driven back by a strong French column of four battalions of the 31st Light Infantry from Heudelet’s Division.

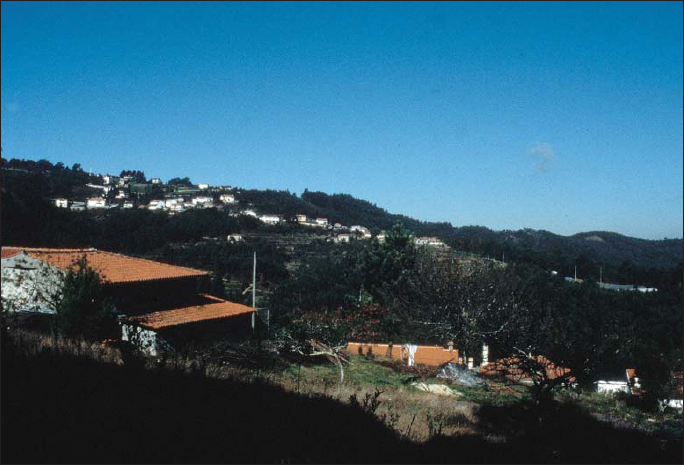

Bussaco ridge looking west from S. Antonio de Cantaro, Gen Reynier’s corps position. (Photo reproduction in Chambers’s 1910 Bussaco)

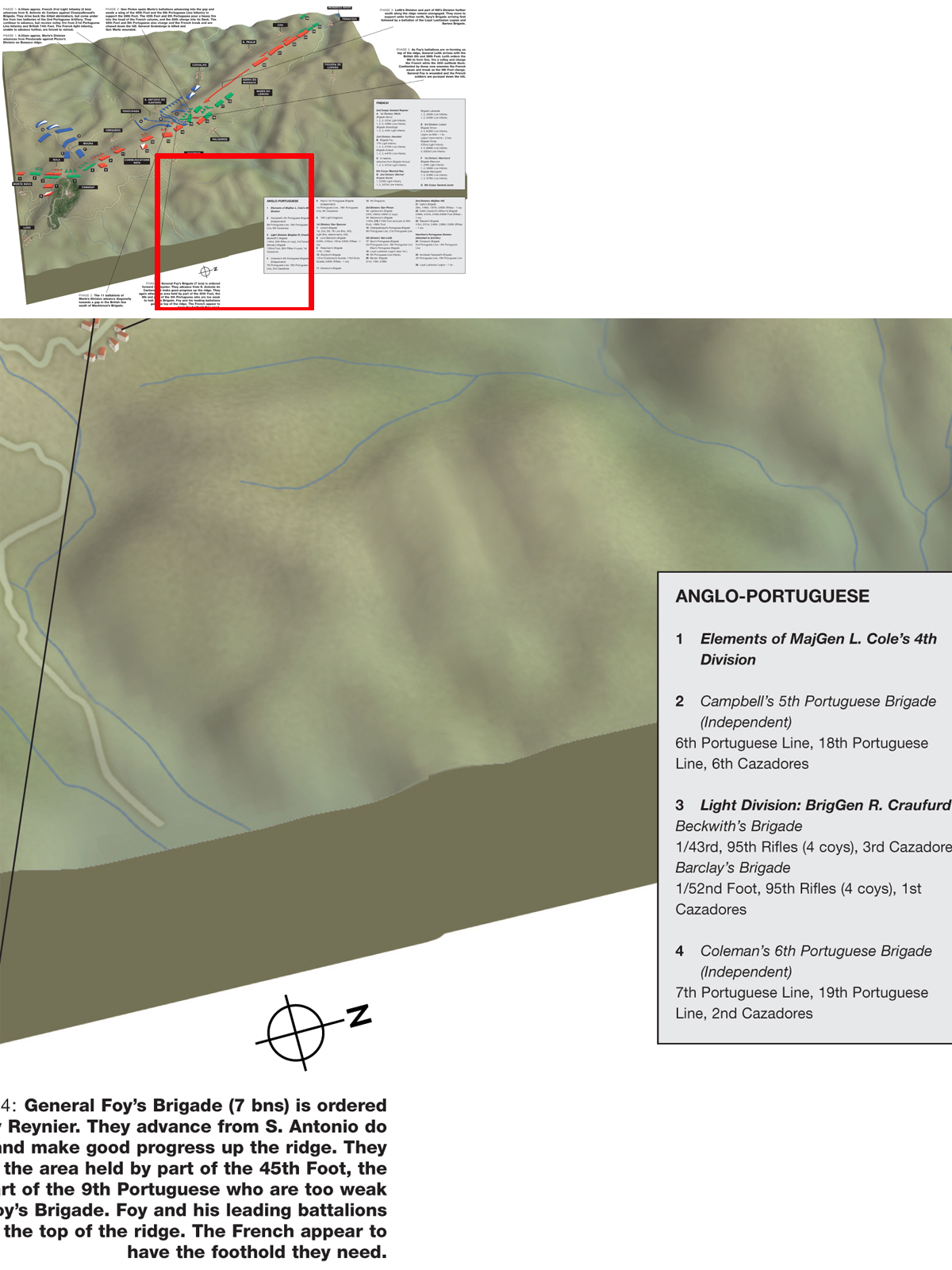

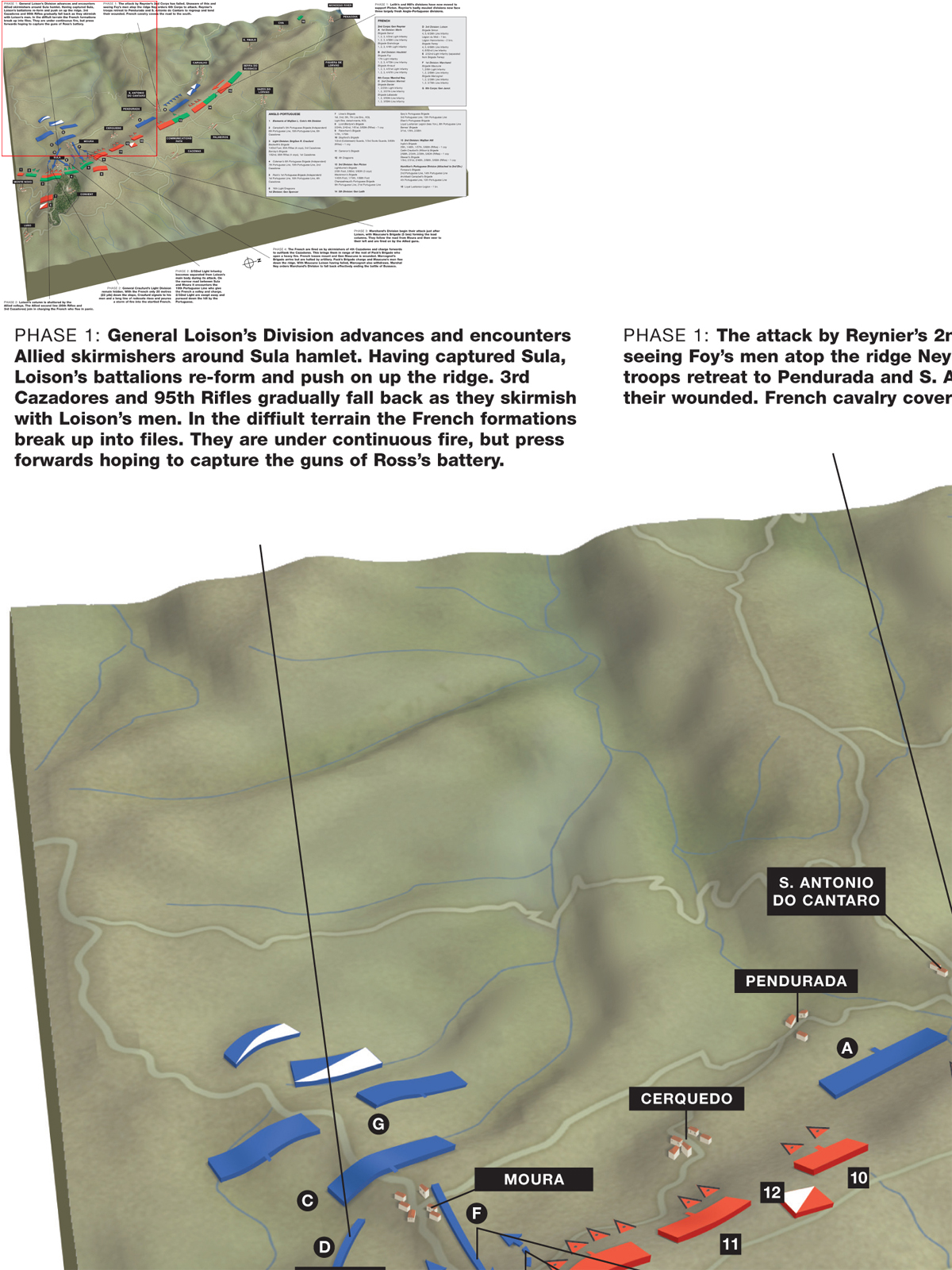

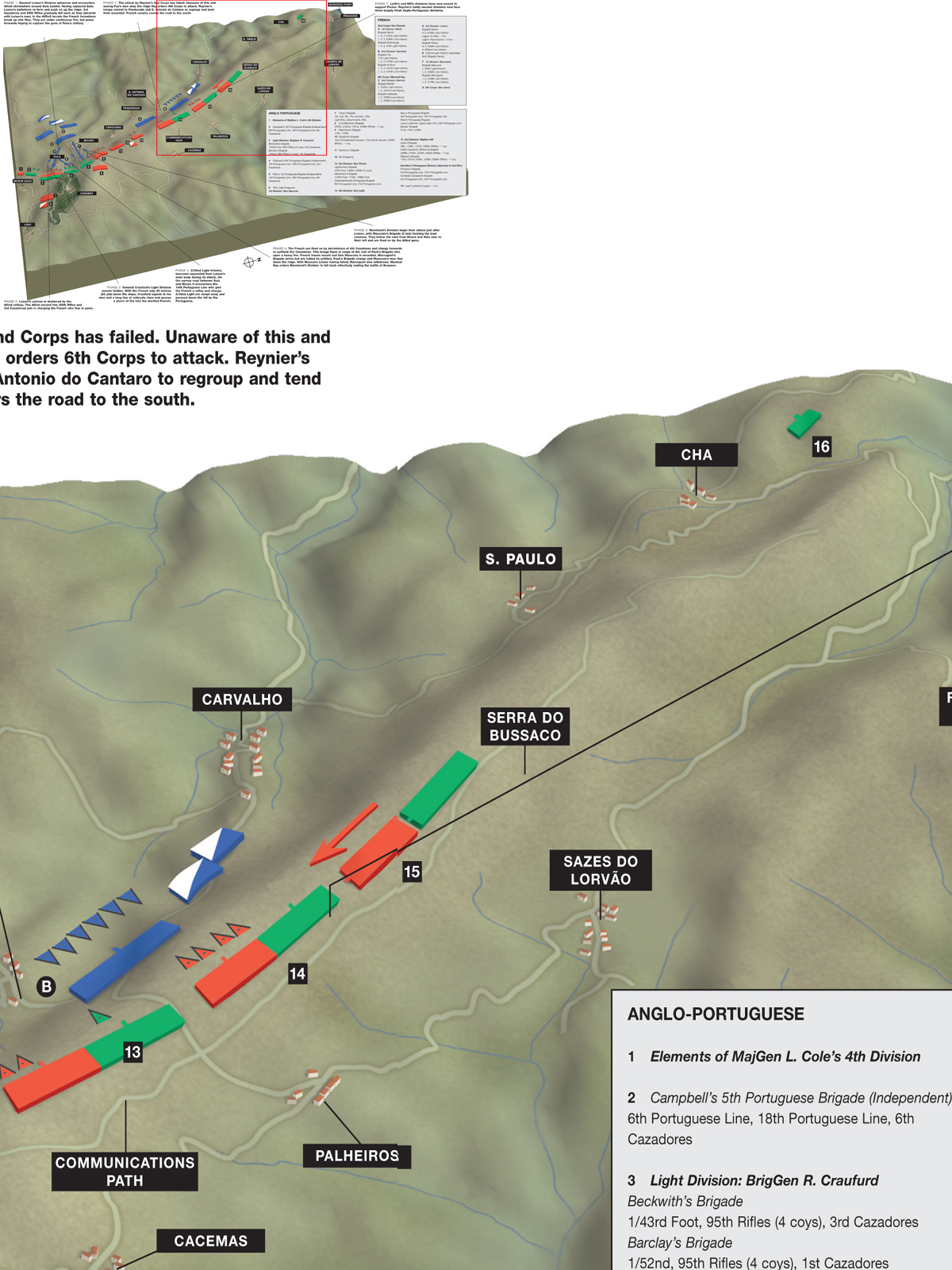

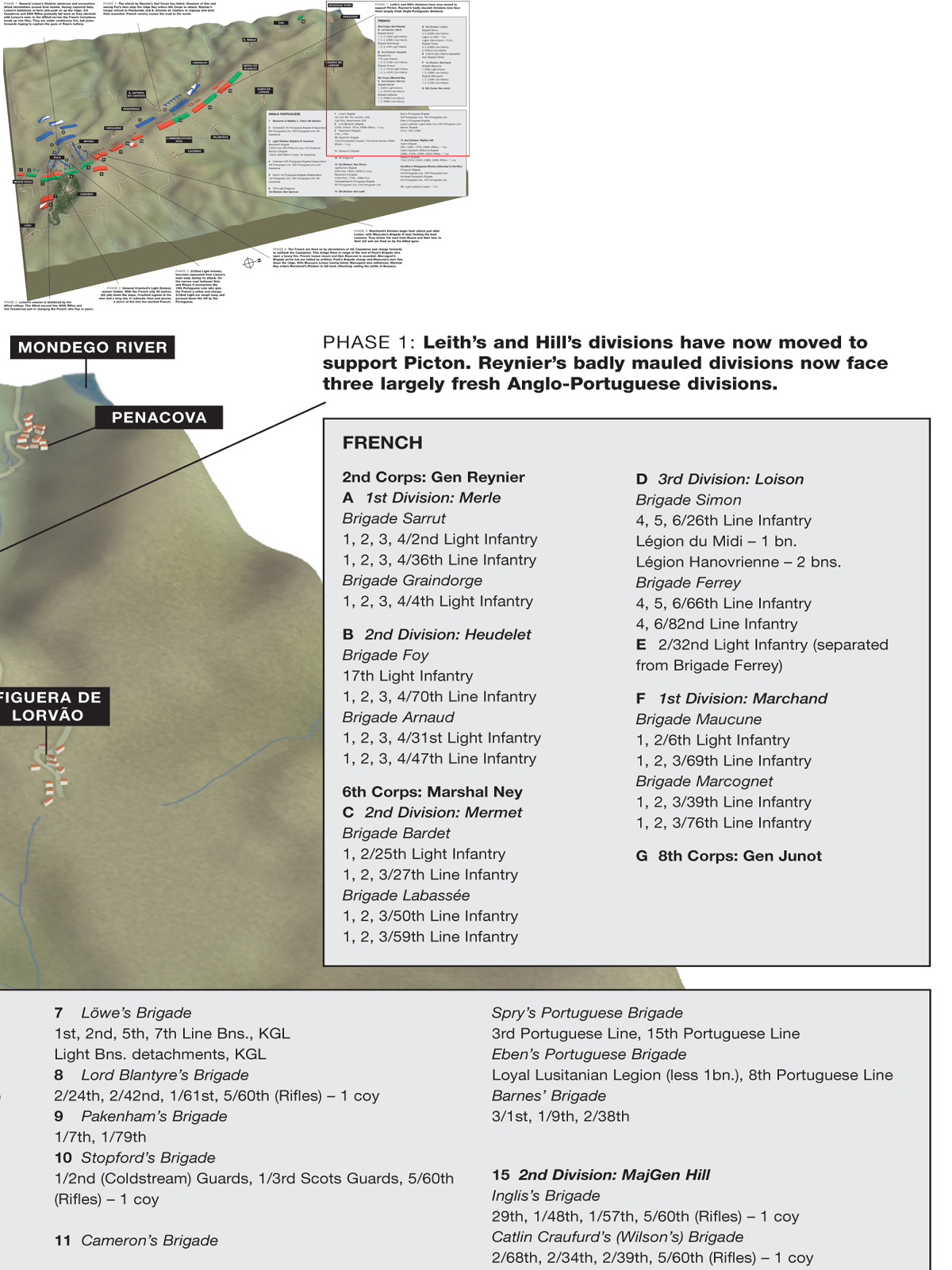

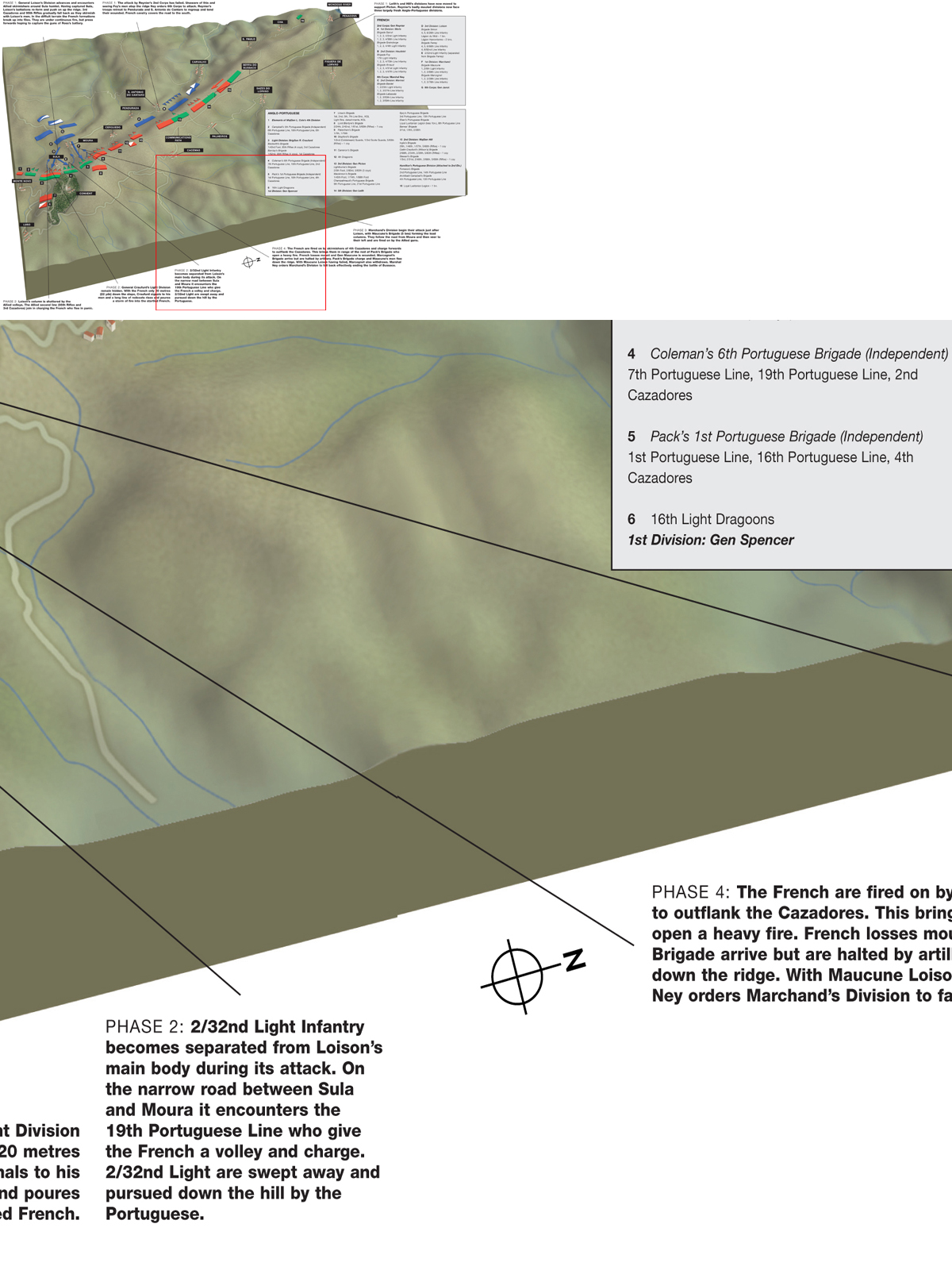

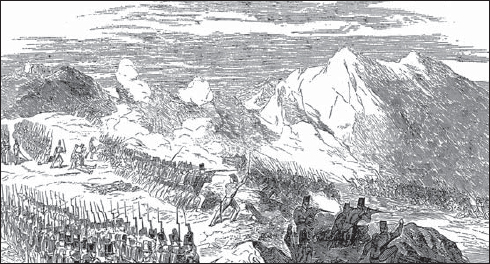

27 September 1810, 6.00am–7.00am, viewed from the west showing the attack of Reynier’s Corps on Picton’s Division and the movement of Leith’s 5th Division and Hill’s 2nd Division to support the line north of their positions.

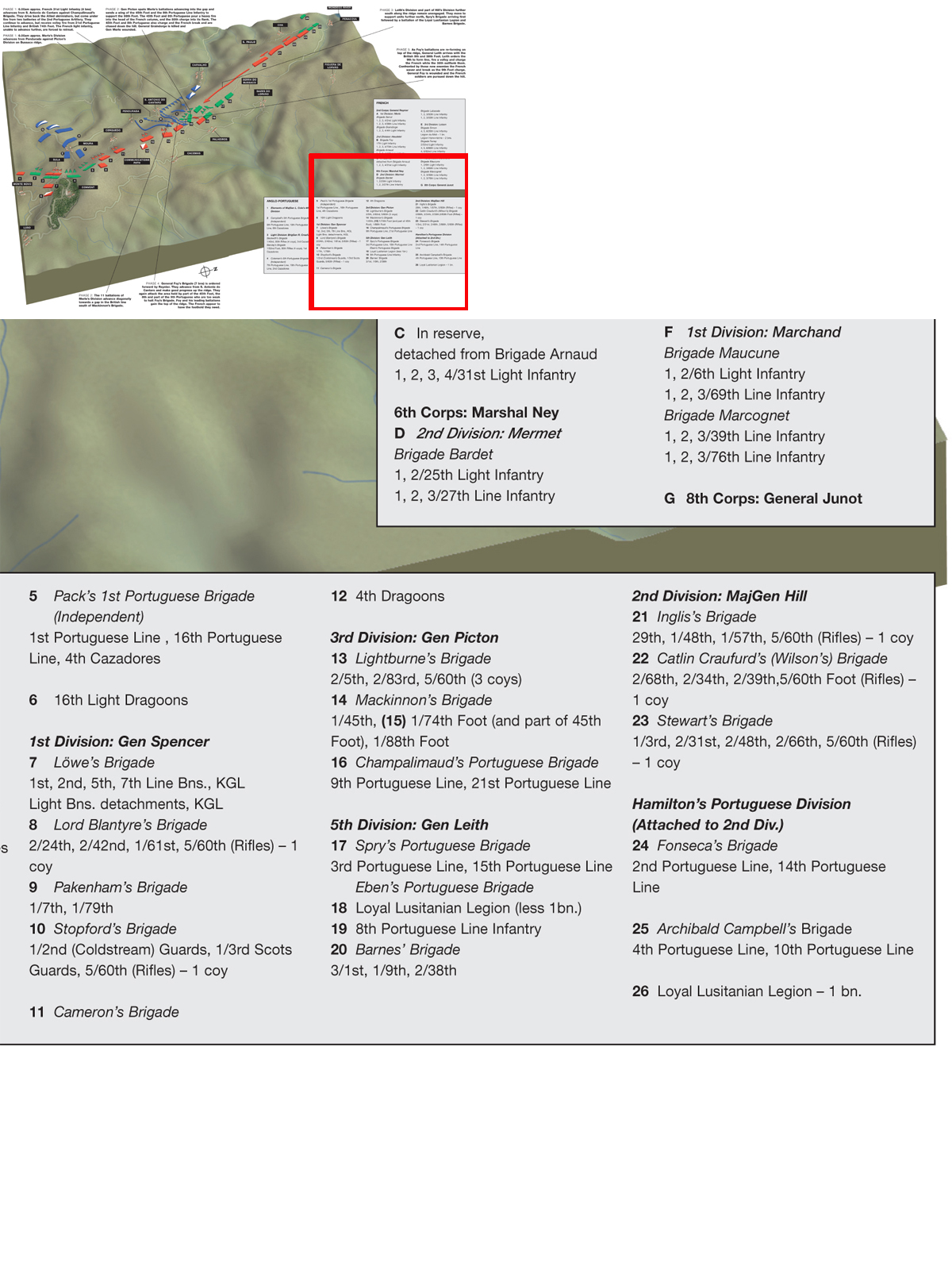

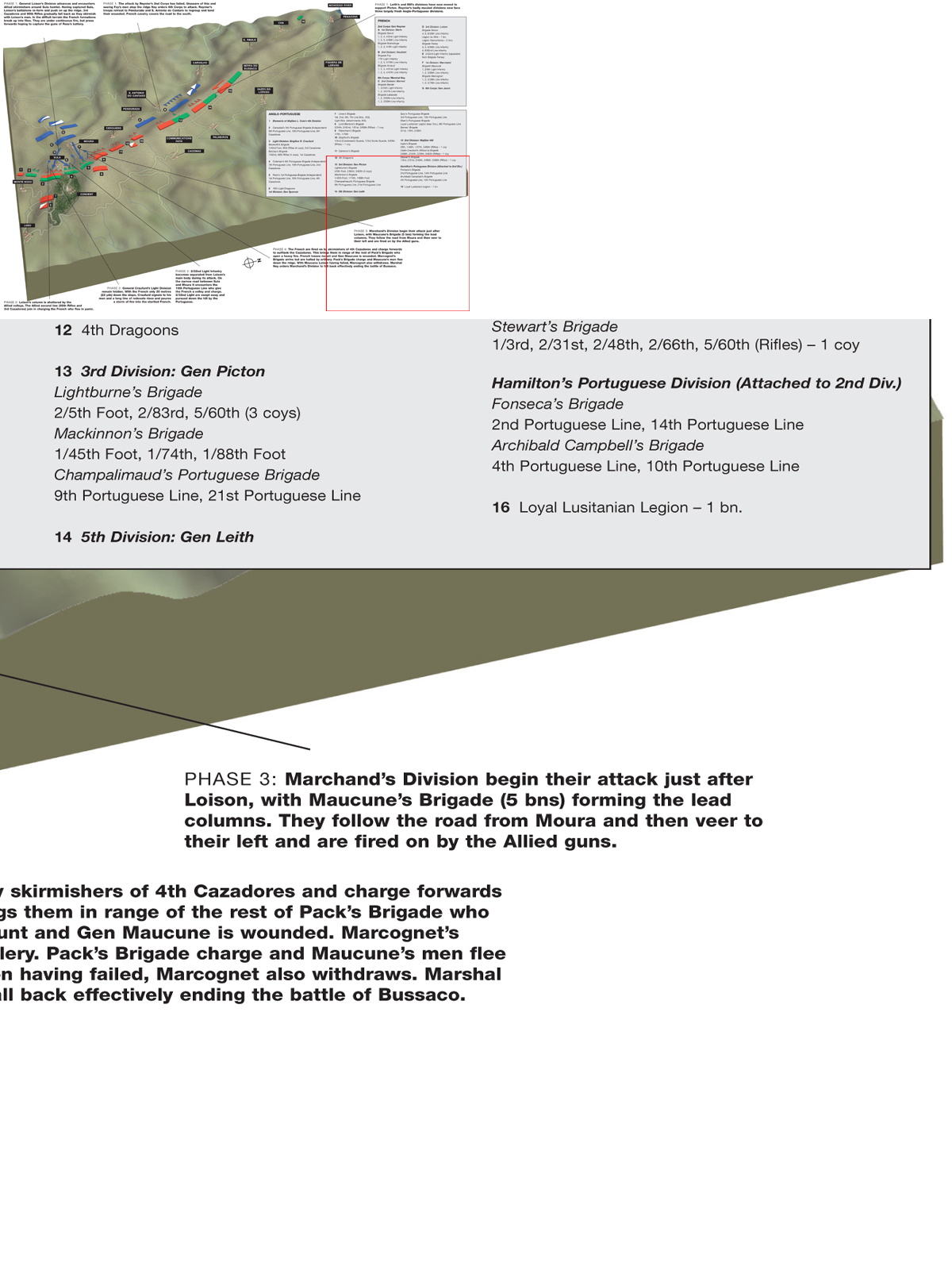

The battle of Bussaco, 27 September 1810. The action shown is that of Picton’s 3rd Division attacked by Reynier’s 2nd Corps. In the foreground, the 88th Foot charges the French column. This was the first battle in which the Portuguese troops with Wellington’s army were heavily engaged. They are shown in the centre wearing dark coatees and led by a mounted officer, possibly illustrating the charge of the 8th Portuguese Infantry. (Print after T. St. Clair)

The fog was now lifting and the Allies could see the French better with each passing minute. Arentschildt’s two batteries of the 2nd Portuguese Artillery opened a telling fire on the French of the 31st Light Infantry, who in spite of heavy losses still advanced until halted by the volleys of the 21st Portuguese and 74th British regiments. For a time the French 31st held their ground but they could go no further. Meanwhile, Merle’s Division was, with difficulty, climbing the ridge more or less diagonally. It now came into view through the mist and one of its regiments managed to reach the crest at an undefended spot just as the men of the 45th Foot and the 8th Portuguese came up to plug the gap. Colonel Wallace of the 88th Foot also saw the danger and, aware that the French might break the Anglo-Portuguese line and establish a foothold on the ridge, ordered the 45th and three companies of the 88th to charge the French column’s flank. At the same time the 8th Portuguese poured a heavy fire into the head of the French columns. Picton, seeing the urgency, led the light companies of the 45th and 88th forward himself. They opened fire on the French only about 60m (200ft) away; tiring rapidly and under intense fire, the four battalions of the French 36th Line Regiment were now charged by the 45th and the 88th. It was the critical moment and the French broke, hurrying down the hill. The 8th Portuguese also charged with Colonel Wallace shouting to his men to press on. They chased the French down the hill until the French artillery opened fire to cover its retreating infantry, then went back up to their positions.

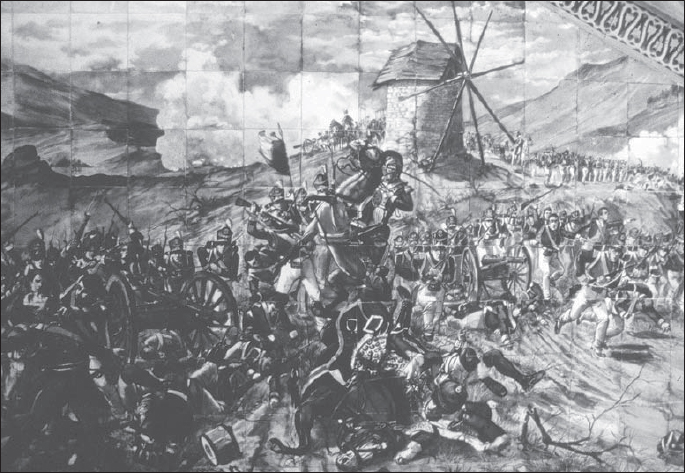

Portuguese infantry overcomes French troops at Bussaco, 27 September 1810. Azujelo by Jorge Colaco done at the end of the 19th century. (Bussaco Palace)

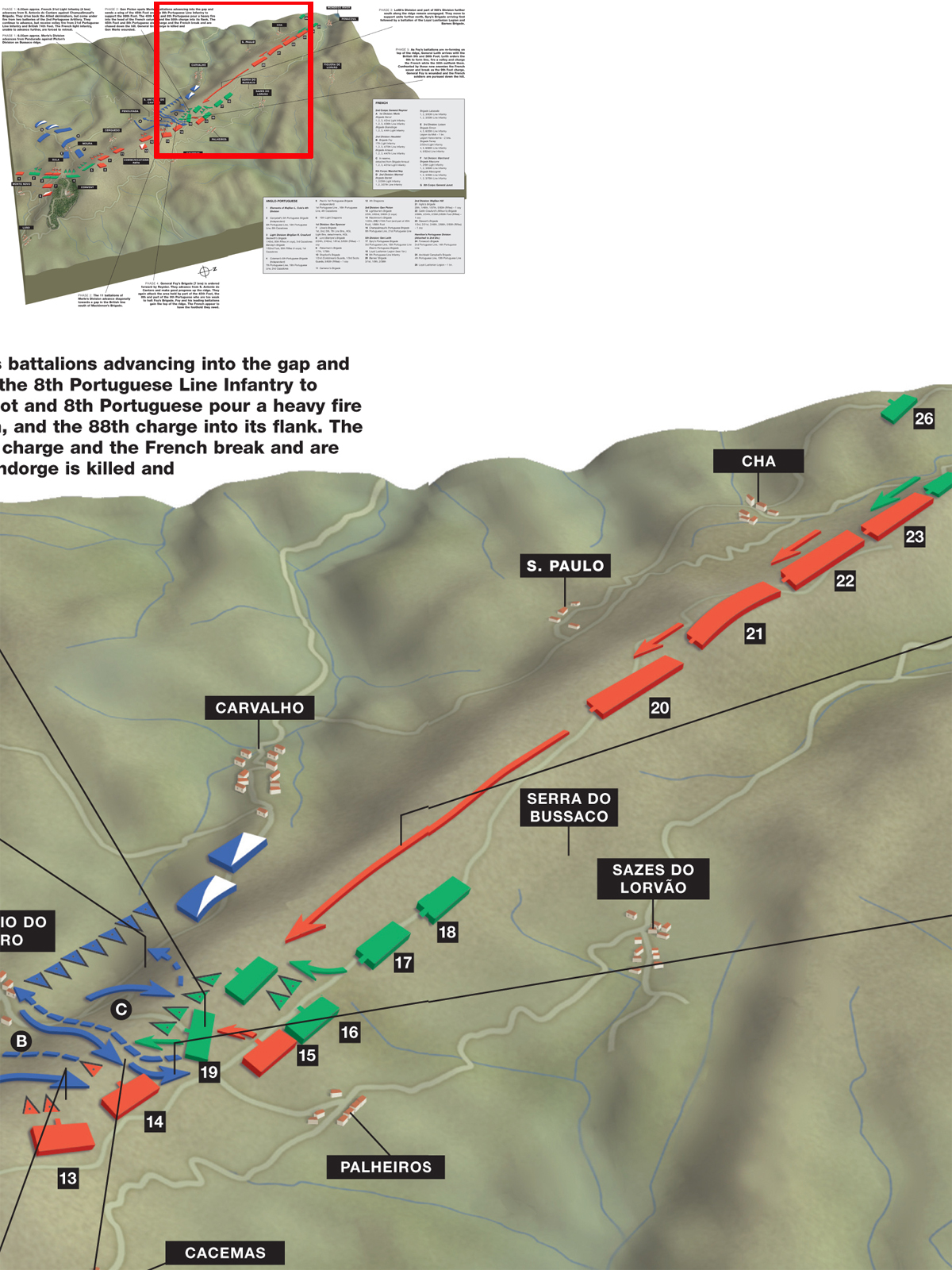

By now the mist was rapidly clearing from the ridge and Reynier could see part of his 2nd Corps’ attack was failing. Through a misunderstanding, BrigGen Foy’s Brigade had not yet ascended the ridge and Reynier now urged it forward. The 17th Light and the 70th Line regiments totalling seven battalions with Foy leading began climbing towards the area held by the right wing of the British 45th Foot, the 8th Portuguese and half of the 9th Portuguese regiment. This force was much too weak to resist Foy’s massed battalions but Allied help was on the way. MajGen Leith, convinced he was under no threat to his front, moved his 5th Division left (or north) to reinforce Picton’s (as instructed by Wellington in such circumstances). Further south, Hill was also under no visible threat and extended part of his 2nd Division to cover the area being vacated by the 5th. The first of Leith’s troops to arrive were Spry’s Portuguese brigade made up of the 3rd and 15th regiments and the Tomar Militia Regiment. They were followed by a battalion of the Loyal Lusitanian Legion and Barnes’s British Brigade consisting of the 3/1st Foot, the 1/9th Foot and the 2/38th Foot with a battery of the 1st Portuguese Artillery. In spite of heavy fire, the French managed to get to the crest of the ridge and drive back the wing of the 45th Foot, the 8th and 9th Portuguese. The regulars of Barnes’s and Spry’s brigades were hurrying to meet the French but the Tomar militiamen panicked and fled before coming under fire.

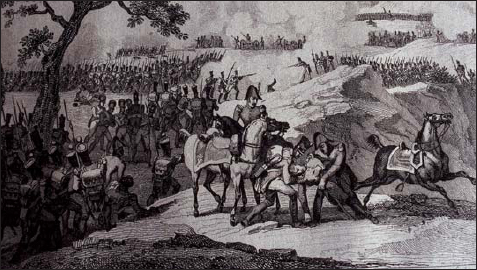

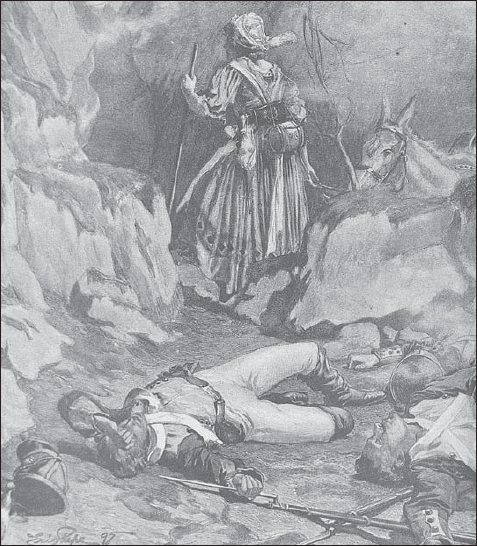

The battle of Bussaco as seen by the French. The wounded officer being carried away in the foreground could be General Foy or General Merle, both of whom were badly wounded during the battle. (Print after Martinet)

General of Brigade Maximilien-Sébastien Foy was an artillery officer of much experience. He had been part of Junot’s army in Portugal during 1807–08 and was promoted brigadier on 3 November 1809. He commanded a brigade in Reynier’s 2nd Corps and was badly wounded at Bussaco. Emerging as one of the best general officers in Masséna’s army, he became general of division on 29 November 1810. He is shown in his artillery uniform.

It looked as though Foy’s Brigade had gained a secure lodgement on the hill and Leith, who was arriving with his troops, even saw a French officer with his hat at the end of his sword cheering with his men. French battalions were quickly moving up and getting into battle formation; the 8th and half of the 9th Portuguese were spread on the hill but could not contain Foy’s much stronger brigade. Leith felt there was still a good chance to succeed. He decided to attack with the 9th Foot while sending the 38th Foot around to outflank. The 9th Foot advanced on the French ‘until we got within a hundred yards of them’, Private James Hale related, ‘when we were ordered to wheel into line and give them a volley, which we immediately did, and saluted them with three cheers and a charge, taking the signal from General Leith who … made the signal by taking off his hat and twirling it over his head. The enemy stood his ground till we got to within twenty yards of them, but seeing that it was our intention to use the bayonet, they took to their heel’ and were chased down the hill by the British until they came under ‘cannon shot and shells’ at which point they fell back, ‘leaving the light companies extended along about the middle of the hill’. By then, Reynier had engaged 22 of his 23 battalions and had lost over 2,000 men against the Allies’ loss of 590. The French had lost over 100 officers including BrigGen Graindorge killed and generals Foy and Merle wounded. The only Allied general officer wounded was Portuguese BrigGen Champalimaud. Picton had only engaged six British and five Portuguese battalions.20

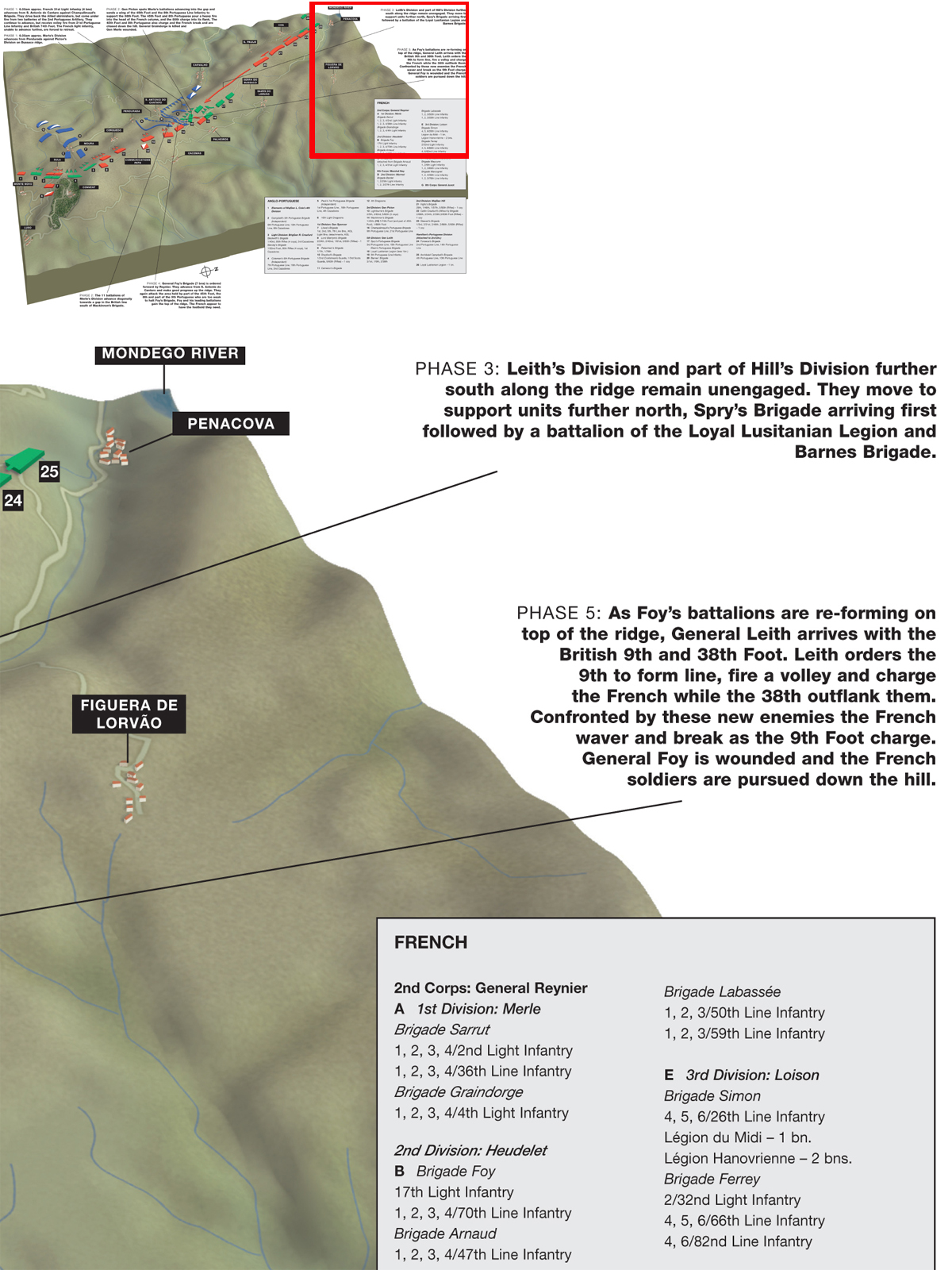

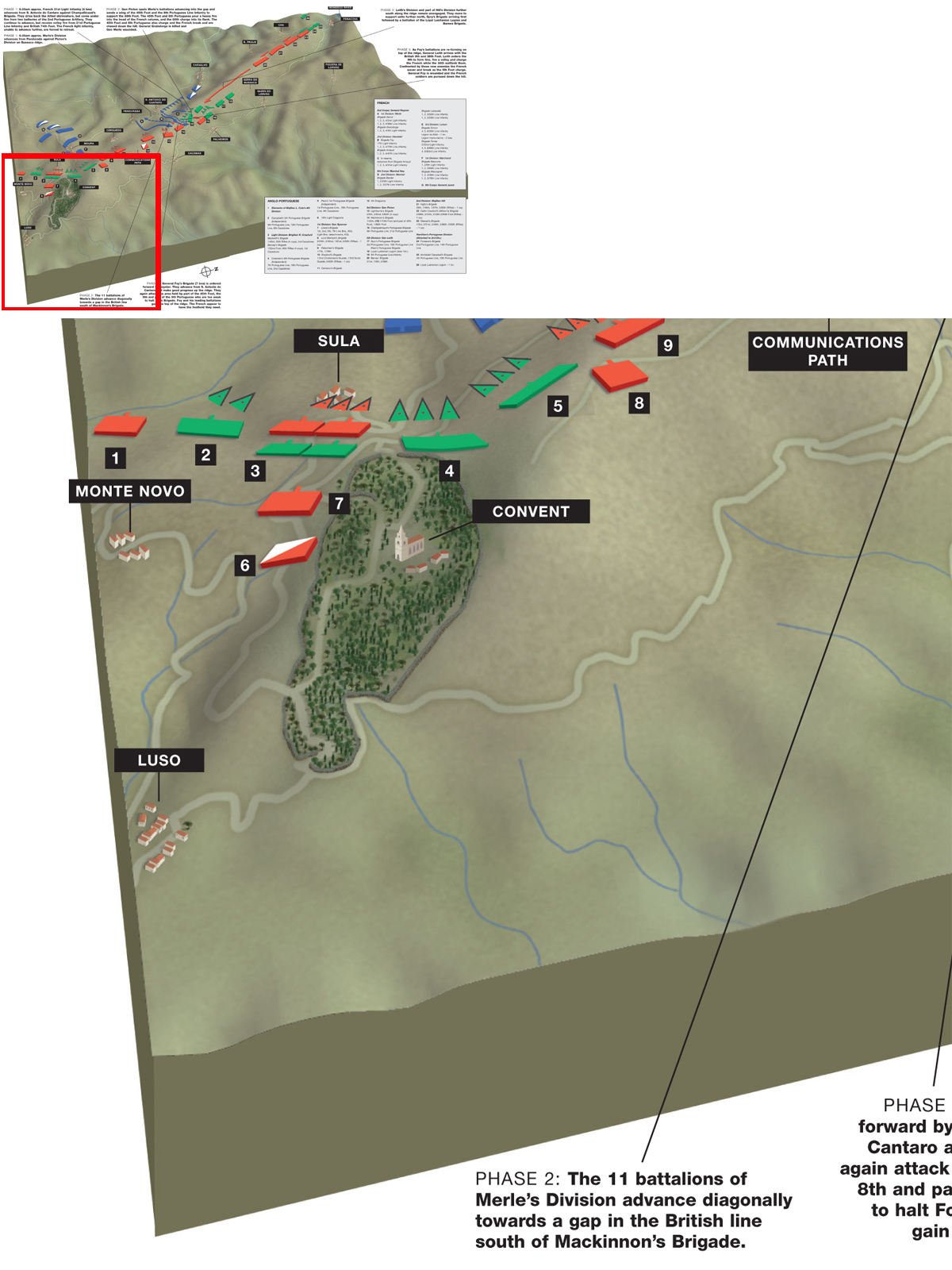

While Reynier’s 2nd Corps attacked, Marshal Ney observed, waiting for the moment when 2nd Corps was ‘master of the heights’ as specified by Marshal Masséna in his orders for the attack on Bussaco. Masséna and his staff officers were near a small windmill just above the village of Moura and would see the attack of Ney’s 6th Corps. As Reynier was 3–4km (1¾ to 2½ miles)away and fog obscured everything, clearly following events may have been difficult. As far as Ney was concerned he followed his own orders to the letter. The mist was lifting and Ney saw what appeared to be Merle’s column reaching the crest. The heights had not been mastered but Foy’s Brigade would shortly seize part of them. Ney gave his 6th Corps the orders to attack. There were two huge attack columns, one led by Marchand on the left, the other by Loison on the right. Loison’s Division would have the worst time climbing the hill as at his point of attack it became very steep from the hamlet of Sula all the way up to the crest. Marchand’s Division would have a better time as it could take the small winding road that would eventually take it to the Bussaco Convent. Mermet’s Division was in reserve.

View of the hills and valleys at Bussaco looking east as seen from Craufurd’s command post. Note how forested the whole area has become compared with photos taken by Chambers at the turn of the 20th century and in earlier prints. (Photo: RC)

General of Division Marchand, commander of the 1st Division of Marshal Ney’s 6th Corps during the Bussaco campaign.

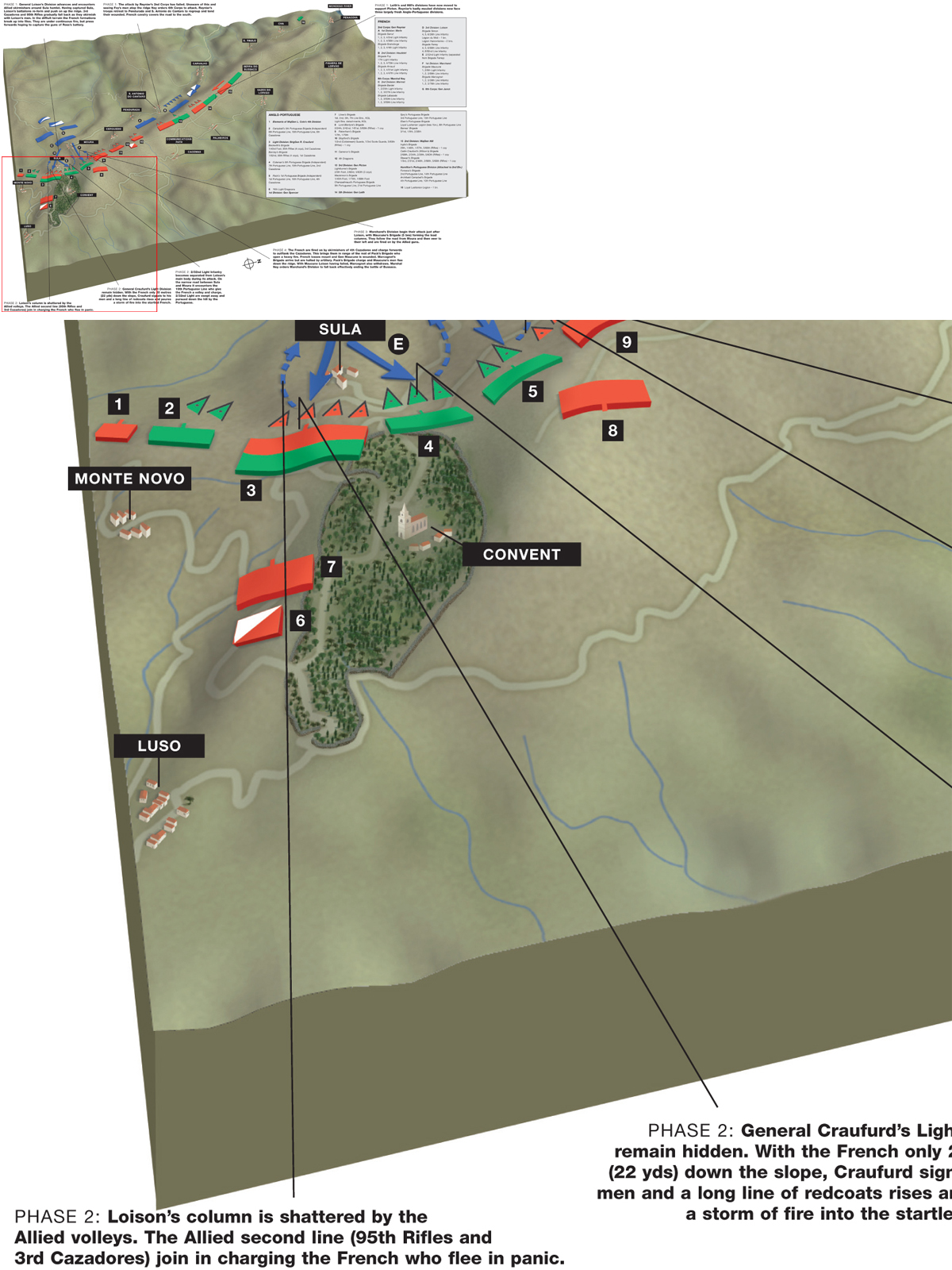

The screen of French skirmishers started up followed by Loison’s and then Marchand’s divisions. Loison was slightly ahead with his two columns, each consisting of a six-battalion brigade, respectively under generals Simon and Ferey, marching up almost side by side. Almost as soon as they left the level ground, the French skirmishers came under fire from the 4th Portuguese Cazadores Battalion, which had been deployed in a forward skirmish line by BrigGen Pack and which retreated, as planned, before the much stronger French. The mist had largely lifted and Loison could see the British and Portuguese troops of Spencer’s 1st Division and the independent brigades on the crest. What he could not see was that Craufurd had his whole Light Division hidden below the crest in roughly two lines above and below Sula. These were the same troops that had previously met the French at the River Coa and at Corunna and they were eager for revenge. Craufurd himself had made the hamlet’s small windmill his command and observation post. His men were lying down, out of sight. Down below, in front of Sula, the 95th Rifles and the 3rd Cazadores opened fire on the French skirmishers – the shock of around 1,300 shots, including about 900 from aimed Baker rifles, caused the advancing French voltigeurs and chasseurs to waver.21 Loison quickly ordered some line infantry battalions to support them, weakening his columns somewhat. With some difficulty the French infantry prevailed and continued its advance on Sula as the riflemen and Cazadores retreated. The hamlet was finally captured, but there the French became the targets of Ross’s Royal Horse Artillery battery posted near Craufurd’s HQ. Cleeves’s King’s German Legion battery also opened up on the French emerging from Sula shortly thereafter.

The village of Sula, the scene of much fighting in 1810. It was still a small hamlet a century later. (Photo reproduction in Chambers’ 1910 Bussaco)

Loison urged his generals to re-form, press their attack and if possible capture the guns. Ross’s battery could be seen up near the windmill only a few hundred metres above Sula. The 95th Rifles and the 3rd Cazadores had rallied and formed a new skirmish line a little above Sula. As the French battalions emerged to climb the hill, they now came under combined rifle, musket and artillery fire. The hill was also steeper. General of Brigade Simon with the three battalions of the 26th French Line Infantry Regiment in front followed a muleteer’s path up going in a file as only a company at a time could get up the narrow path. General of Brigade Ferey found no path for his brigade and his battalions climbed as best they could. Men in both brigades were being picked off by the snipers of the 95th Rifles and 3rd Cazadores as the latter conducted a fighting retreat up the hill, forcing the French to return fire as well as climb. But the French soldiers would inevitably prevail as they were far more numerous and, given a chance, would take the guns at the windmill. There were less and less troops to oppose them as they pressed forward, the Allied skirmishers in green and brown uniforms retreating before them. Or so they thought …

Sula in 2000 seen from Masséna’s observation post next to the Moura mill. Sula has more houses and vegetation than 100 years ago and is certainly larger than in 1810. (Photo: RC)

Craufurd had a nasty surprise in store for the struggling French soldiers. There was a narrow path passing just above the mill. This path could barely be seen from lower down. There, lying flat on the ground, were the 43rd and 52nd light infantry regiments of the Light Division, the former having 800 men and the latter 950, a total of 1,750 fresh troops eager to engage the French. At the windmill, near a large rock, Craufurd was watching the progress of the two French columns who were courageously advancing in spite of the fire they endured, notably from Ross’s guns just to the left of Craufurd at the windmill. Despite substantial losses they struggled to within about 20 metres (65ft) of the windmill and Ross’s battery. The skirmishers of the 95th Rifles and the 3rd Cazadores were now streaming past Ross’s battery, some staying near the guns and the mill. Craufurd was there carefully watching the hopeful French; they were forming for a last gallant rush to take the guns.

Just as the French soldiers were about to charge, Craufurd waved his hat to the 43rd and 52nd, the agreed signal, and is said to have shouted: ‘Now 52nd, avenge the death of Sir John Moore!’ – a long line of redcoats in two ranks suddenly appeared in front of the startled French soldiers. Moments later a tremendous volley thundered from the British line shattering in an instant the heads of the French columns. The dazed survivors amidst heaps of dead and wounded were in no position to reply while the British reloaded and fired again. Three companies of the 43rd and three of the 52nd were fanning out to each flank to create a deadly crossfire. The skirmishers of the 95th Rifles and the 3rd Cazadores had re-formed and now supported the 43rd and 52nd. The remaining French showed the bravery of desperation – some returned fire, others charged, all in vain. BrigGen Simon, who had charged at the head of his men, was wounded in the jaw and captured by a private of the 52nd. The British troops kept firing and then the 43rd, 52nd, 3rd Cazadores and 95th Rifles all charged; the French who could still stand broke and fled, tumbling into their comrades further down the hill who were trying to climb up. This scene of utter disorder spread to all the French columns, who fell back pell mell. The Allied artillery continued to fire and panic overcame the French columns as the Allied battalions counter-charged down the steep hill. Some swept well past Sula looking to bayonet any French they could catch.

27 September 1810, 7.00am–8.00am, viewed from the west showing the attack of Ney’s 6th Corps on the northern part of the British line, and their repulse with heavy loss by Craufurd’s Light Division and Pack’s Portuguese Brigade.

Craufurd’s command post was at this windmill in 1810. It was still an operational windmill when this photo was taken for Chambers’s 1910 Bussaco.

During the attack, the 2nd Battalion of the French 32nd Light Infantry became separated from Ferey’s brigade but was nevertheless pushing forward further to the right up the narrow road from Moira to Sula. Wellington’s dispatch of the battle mentioned a ‘determined and very successful attack’ with bayonet was made by the five companies making up the 1st Battalion of the 19th Portuguese Regiment under LtCol Macbean when the enemy ‘attempted to maintain himself, the 19th continued to move on, gave him a volley and charged’. This drove the French ‘headlong down the steep: a heavy [French] battery opened upon them [the 19th Portuguese] from the opposite side of the ravine; the regiment immediately, under the fire, reformed, faced to the right about, and as if manoeuvring on a parade, regained its original position, amid the acclamations of all the left of the British Army who were spectators to their conduct’ according to information sent to Beresford.22

In less than 20 minutes from Craufurd’s order, Loison’s Division had been routed with great loss. Some 21 officers had been killed, 47 wounded and some 1,200 casualties suffered amongst the enlisted men out of a force of 6,500. The Allies had taken only about 150 casualties and no senior officers hit. The engagement had lasted about an hour, the final and bloodiest phase from when Craufurd ordered his men up perhaps 15–20 minutes. Craufurd’s men and the 19th Portuguese retired up the hill as the French artillery was now shooting at them and the French 25th Light Infantry was sent by General Mermet to cover Loison’s fleeing division.

The Sula windmill, Craufurd’s command post during the battle as seen today. (Photo: RC)

While Loison’s assault was breaking on the rock of Craufurd’s Light Division, Marchand’s Division was also attacking on the French left. The leading column consisted of Maucune’s Brigade: five battalions from the 6th Light and 69th Line regiments. They followed the road up from Moura but soon came under heavy fire from Cleeves’s, Parros’s and Lawson’s batteries as they veered to the right. Nearing a wooded area, they now came under fire from skirmishers of the 4th Cazadores concealed behind the pine trees above. They had been detached by BrigGen Pack, whose independent Portuguese brigade was further up at the crest. Under this galling fire the French soldiers – seemingly without orders to do so – spontaneously charged up the hill to outflank the Cazadores in which they succeeded. But in so doing, they came upon the 1st and 16th Portuguese infantry regiments – over 2,100 men – of Pack’s Brigade who poured a torrential fire on the French. They suffered heavy casualties including General of Brigade Maucune, who was wounded. The second brigade of Marchand’s Division was also coming up under General of Brigade Marcognet but halted when it began receiving Allied artillery fire. By now a charge was driving Maucune’s men back down and many French soldiers could see that, to their right, Loison’s attack had failed. Maucune’s Brigade had taken about 850 casualties and Marcognet’s about 300.

With the attack of Reynier’s 2nd Corps having failed, Loison’s Division beaten off and Marchand’s about to suffer the same fate, Marshal Ney decided to sound the retreat. It was now about 8.00am. Both divisions retired behind Moura but Ney sent out a line of skirmishers which kept the Allied light troops busy for the rest of the morning. There were no further movements and the battle was reduced to random musket fire between skirmishers and the occasional cannon shot.

Marshal Masséna had been watching, largely helplessly, the progress and failures of 6th Corps near a windmill just above the village of Moura while receiving news that 2nd Corps had also been thrown back and that casualties were very substantial. Once he knew that both attacks had failed, there was little else he could do. Sending in Junot’s 8th Corps would have only added to the already considerable slaughter in his army. And while the French still had about 20,000 fresh infantrymen, he rightly suspected Wellington also still had plenty of fresh troops. The French had suffered 4,498 casualties including 522 killed, 3,612 wounded and 364 missing in 2nd and 6th corps according to returns. There were at least 100 in other formations, with total French casualties amounting to 4,600. But it may have been closer to 5,834 according to Chambers, who, with some justification, did not trust the accuracy of the French returns. Marbot, who was there with Masséna’s staff watching at the Moura windmill, termed the battle ‘one of the most terrible setbacks ever inflicted on the French armies’, adding that the casualties had been nearly 5,000.23

The Men of Marshal Ney’s 6th Corps struggled up the ridge driving back the Allied skirmishers until they seemed poised to capture the guns of Ross’s battery. But concealed in dead ground little more than 20 metres in front of them was Craufurd’s Light Division. As the French approached Craufurd waved his hat and shouted ‘Now 52nd, avenge the death of Sir John Moore!’ At their commander’s signal the men of the 43rd and 52nd light infantry rose as if from out of the ground — a long line of redcoats in two ranks. Seconds later, a tremendous volley thundered from the British line smashing the heads of the French columns. The French attack was stopped in its tracks. (Patrice Courcelle)

A ‘cantinière’ of the French 26th Line Infantry hearing that BrigGen Simon had been wounded and taken prisoner loaded his effects on her donkey and started up the hill saying ‘let’s see if the English will dare to kill a woman’. The Allied soldiers seeing her did not shoot and let her cross the ‘no man’s land’. Reaching the top, a British officer took her to Gen Simon. She looked after him for several days and then rejoined her unit. This incident is reported in Marbot’s memoirs. (Print after Eric Pape)

Wellington, at his command post on one of the highest spots of Bussaco, had observed everything, ensuring that the French would not break through by providing sufficient reserves. Following the attacks, Wellington sent in Hill’s 2nd Division as reinforcements so that the areas previously attacked were now defended by around 10,000 more men. The Allied thus had at least 33,000 men who had not yet fired a shot besides those that had been engaged. Preliminary reports stated that losses had been relatively light and that all units that had been under fire were still in fighting condition. The British and Portuguese expected a renewed effort but it did not come. Later that day, some French skirmishers once again came up. The men of the Light Division being tired, Wellington sent the 6th Cazadores and the light companies from Löwe’s Brigade of the King’s German Legion to skirmish while a company of the 43rd chased some French out of Sula. More attacks were expected but, except for the occasional exchanges between skirmishers, none came. The casualty reports that eventually reached Wellington were most satisfying: the Allied army only had 1,252 casualties including 200 killed, 1,001 wounded and 51 missing.

Charge of Portuguese Cazadores at Bussaco, 27 September 1810. Azujelo by Jorge Colaco done at the end of the 19th century. (Bussaco Palace)

Craufurd’s Light Division repulses Loison’s French Division from Ney’s 6th Corps.

Bussaco ridge showing the old road going to Sula. This is most likely the area where the 19th Portuguese charged and routed Ferey’s French brigade. (Photo reproduction in Chambers’s 1910 Bussaco)

The Moura windmill, Masséna’s command post during the battle. (Photo: RC)

Wellington’s command post at Bussaco. This is one of the highest spots in the whole area. (Photo: RC)

View of Bussaco ridge looking south from Masséna’s command post. (Photo: RC)

View looking east from Wellington’s command post. (Photo: RC)

20 Pvt Hale’s account is quoted in F. Lorraine Petre, The History of the Norfolk Regiment 1685–1918 (Norwich, n.d.), I, p. 209. Portuguese regiments were then divided into two battalions of five companies each. The full 8th and 9th and half of the 21st Portuguese were engaged. British regiments had ten companies per battalion usually divided into two ‘wings’ so that it could also be counted as two and a half battalions for a total of only eight and a half battalions in British terms. The Tomar Militia Regiment had fled before coming under fire. Except for the light companies of the British 5th and 83rd, the rest of Picton’s and Leith’s divisions were not engaged. It is interesting to note that, despite the relatively small number of Allied troops actually engaged, Reynier thought he had been repulsed by a force three times as strong as his attack columns.

21 Oman states that the 95th Rifles had some 700 rifles, which is correct, and the 3rd Cazadores had 600 rifles, which is not. From August 1810, the six Portuguese Cazadores battalions would have had a maximum of about 200 rifles each. D’Urban specifically mentions 200 rifles ordered issued to the 1st, 3rd and 6th Cazadores in the 6–7 August 1810 entry of his journal. The other 400 men having British India Pattern smooth-bore muskets. The 2,000 Baker rifles were ordered in March and June 1809 for the Cazadores and received at the Portuguese army’s magazine in Lisbon in late June 1810 (PRO, WO 1/239 and AO 3/757).

22 Wellington’s dispatch to the Earl of Liverpool regarding the battle of Bussaco was written at Coimbra on 30 September 1810 (PRO, FO 63/100). It was published in the London Gazette of 15 October 1810. Macbean’s and Beresford’s accounts are from Chambers, p. 122.

23 Marbot, II, p. 394. Chambers felt the French had 2,000 killed, 3,580 wounded and 254 prisoners for a total of 5,834. Marbot added the British and Portuguese had ‘by their own admission’ sustained 2,300 casualties (!) and also mentioned that if the French had attacked the previous day, 25,000 men of Wellington’s best troops were still south of the Mondego and Masséna would have carried the position easily. This has been (and still is) often stated in French sources. This seems to refer to Hill’s 2nd Division of 10,000 men but the rest of Wellington’s army was already at Bussaco. Howard’s Bussaco offers some slight variations over Oman’s usually accepted figures.