His name is Three-phasing and he is bald and wrinkled, slightly over one meter tall, large-eyed, toothless and all bones and skin, sagging pale skin shot through with traceries of delicate blue and red. He is considered very beautiful but most of his beauty is in his hands and is due to his extreme youth. He is over two hundred years old and is learning how to talk. He has become reasonably fluent in sixty-three languages, all dead ones, and has only ten to go.

The book he is reading is a facsimile of an early edition of Goethe’s Faust. The nervous angular Fraktur letters goose-step across pages of paper-thin platinum.

The Faust had been printed electrolytically and, with several thousand similarly worthwhile books, sealed in an argon-filled chamber and carefully lost, in 2012 A.D.; a very wealthy man’s legacy to the distant future.

In 2012 A.D., Polaris had been the pole star. Men eventually got to Polaris and built a small city on a frosty planet there. By that time, they weren’t dating by prophets’ births any more, but it would have been around 4900 A.D. The pole star by then, because of precession of the equinoxes, was a dim thing once called Gamma Cephei. The celestial pole kept reeling around, past Deneb and Vega and through barren patches of sky around Hercules and Draco; a patient clock but not the slowest one of use, and when it came back to the region of Polaris, then 26,000 years had passed and men had come back from the stars, to stay, and the book-filled chamber had shifted 130 meters on the floor of the Pacific, had rolled into a shallow trench, and eventually was buried in an underwater landslide.

The thirty-seventh time this slow clock ticked, men had moved the Pacific, not because they had to, and had found the chamber, opened it up, identified the books and carefully sealed them up again. Some things by then were more important to men than the accumulation of knowledge: in half of one more circle of the poles would come the millionth anniversary of the written word. They could wait a few millenia.

As the anniversary, as nearly as they could reckon it, approached, they caused to be born two individuals: Nine-hover (nominally female) and Three-phasing (nominally male). Three-phasing was born to learn how to read and speak. He was the first human being to study these skills in more than a quarter of a million years.

Three-phasing has read the first half of Faust forwards and, for amusement and exercise, is reading the second half backwards. He is singing as he reads, lisping.

“Fain’ Looee w’mun … wif all’r die-mun ringf …” He has not put in his teeth because they make his gums hurt.

Because he is a child of two hundred, he is polite when his father interrupts his reading and singing. His father’s “voice” is an arrangement of logic and aesthetic that appears in Three-phasing’s mind. The flavor is lost by translating into words:

“Three-phasing my son-ly atavism of tooth and vocal cord,” sarcastically in the reverent mode, “Couldst tear thyself from objects of manifest symbol, and visit to share/help/learn, me?”

“?” He responds, meaning “with/with/of what?”

Withholding mode: “Concerning thee: past, future.”

He shuts the book without marking his place. It would never occur to him to mark his place, since he remembers perfectly the page he stops on, as well as every word preceding, as well as every event, no matter how trivial, that he has observed from the precise age of one year. In this respect, at least, he is normal.

He thinks the proper coordinates as he steps over the mover-transom, through a microsecond of black, and onto his father’s mover-transom, about four thousand kilometers away on a straight line through the crust and mantle of the earth.

Ritual mode: “As ever, father.” The symbol he uses for “father” is purposefully wrong, chiding. Crude biological connotation.

His father looks cadaverous and has in fact been dead twice. In the infant’s small-talk mode he asks “From crude babblings of what sort have I torn your interest?”

“The tale called Faust, of a man so named, never satisfied with {symbol for slow but continuous accretion} of his knowledge and power; written in the language of Prussia.”

“Also depended-ing on this strange word of immediacy, your Prussian language?”

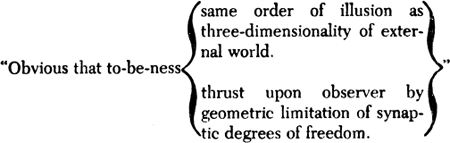

“As most, yes. The word of ‘to be’: sein. Very important illusion in this and related languages/cultures; that events happen at the ‘time’ of perception, infinitesimal midpoint between past and future.”

“Convenient illusion but retarding.”

“As we discussed 129 years ago, yes.” Three-phasing is impatient to get back to his reading, but adds:

“You always stick up for them.”

“I have great regard for what they accomplished with limited faculties and so short lives.” Stop beatin’ around the bush, Dad. Tempis fugit, eight to the bar. Did Mr. Handy Moves-dat-man-around-by-her-apron-strings, 20th-century American poet, intend cultural translation of Lysistrata? if so, inept. African were-beast legendry, yes.

Withholding mode (coy): “Your father stood with Nine-hover all morning.”

“,” broadcasts Three-phasing: well?

“The machine functions, perhaps inadequately.”

The young polyglot tries to radiate calm patience.

“Details I perceive you want; the idea yet excites you. You can never have satisfaction with your knowledge, either. What happened-s to the man in your Prussian book?”

“He lived-s one hundred years and died-s knowing that a man can never achieve true happiness, despite the appearance of success.”

“For an infant, a reasonable perception.”

Respectful chiding mode: “One hundred years makes-ed Faust a very old man, for a Dawn man.”

“As I stand,” same mode, less respect, “yet an infant.” They trade silent symbols of laughter.

After a polite tenth-second interval, Three-phasing uses the light interrogation mode: “The machine of Nine-hover …?”

“It begins to work but so far not perfectly.” This is not news.

Mild impatience: “As before, then, it brings back only rocks and earth and water and plants?”

“Negative, beloved atavism.” Offhand: “This morning she caught two animals that look as man may once have looked.”

“!” Strong impatience, “I go?”

“.” His father ends the conversation just two seconds after it began.

Three-phasing stops off to pick up his teeth, then goes directly to Nine-hover.

A quick exchange of greeting-symbols and Nine-hover presents her prizes. “Thinking I have two different species,” she stands: uncertainty, query.

Three-phasing is amused. “Negative, time-caster. The male and female took very dissimilar forms in the Dawn times.” He touches one of them. “The round organs, here, served-ing to feed infants, in the female.”

The female screams.

“She manipulates spoken symbols now,” observes Nine-hover.

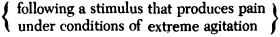

Before the woman has finished her startled yelp, Three-phasing explains: “Not manipulating concrete symbols; rather, she communicates in a way called ‘non-verbal,’ the use of such communication predating even speech.” Slipping into the pedantic mode: “My reading indicates that such a loud noise occurs either  since she seems not in pain, then she must fear me or you or both of us.

since she seems not in pain, then she must fear me or you or both of us.

“Or the machine,” Nine-hover adds.

Symbol for continuing. “We have no symbol for it but in Dawn days most humans observed ‘xenophobia,’ reacting to the strange with fear instead of delight. We stand as strange to them as they do to us, thus they register fear. In their era this attitude encouraged-s survival.

“Our silence must seem strange to them, as well as our appearance and the speed with which we move. I will attempt to speak to them, so they will know they need not fear us.”

Bob and Sarah Graham were having a desperately good time. It was September of 1951 and the papers were full of news about the brilliant landing of U.S. Marines at Inchon. Bob was a Marine private with two days left of the thirty days’ leave they had given him, between boot camp and disembarkation for Korea. Sarah had been Mrs. Graham for three weeks.

Sarah poured some more bourbon into her Coke. She wiped the sand off her thumb and stoppered the Coke bottle, then shook it gently. “What if you just don’t show up?” she said softly.

Bob was staring out over the ocean and part of what Sarah said was lost in the crash of breakers rolling in. “What if I what?”

“Don’t show up.” She took a swig and offered the bottle. “Just stay here with me. With us.” Sarah was sure she was pregnant. It was too early to tell, of course; her calendar was off but there could be other reasons.

He gave the Coke back to her and sipped directly from the bourbon bottle. “I suppose they’d go on without me. And I’d still be in jail when they came back.”

“Not if—”

“Honey, don’t even talk like that. It’s a just cause.”

She picked up a small shell and threw it toward the water.

“Besides, you read the Examiner yesterday.”

“I’m cold. Let’s go up.” She stood and stretched and delicately brushed sand away. Bob admired her long naked dancer’s body. He shook out the blanket and draped it over her shoulders.

“It’ll all be over by the time I get there. We’ll push those bastards—”

“Let’s not talk about Korea. Let’s not talk.”

He put his arm around her and they started walking back toward the cabin. Halfway there, she stopped and enfolded the blanket around both of them, drawing him toward her. He always closed his eyes when they kissed, but she always kept hers open. She saw it: the air turning luminous, the seascape fading to be replaced by bare metal walls. The sand turns hard under her feet.

At her sharp intake of breath, Bob opens his eyes. He sees a grotesque dwarf, eyes and skull too large, body small and wrinkled. They stare at one another for a fraction of a second. Then the dwarf spins around and speeds across the room to what looks like a black square painted on the floor. When he gets there, he disappears.

“What the hell?” Bob says in a hoarse whisper.

Sarah turns around just a bit too late to catch a glimpse of Three-phasing’s father. She does see Nine-hover before Bob does. The nominally-female time-caster is a flurry of movement, sitting at the console of her time net, clicking switches and adjusting various dials. All of the motions are unnecessary, as is the console. It was built at Three-phasing’s suggestion, since humans from the era into which they could cast would feel more comfortable in the presence of a machine that looked like a machine. The actual time net was roughly the size and shape of an asparagus stalk, was controlled completely by thought, and had no moving parts. It does not exist any more, but can still be used, once understood. Nine-hover has been trained from birth for this special understanding.

Sarah nudges Bob and points to Nine-hover. She can’t find her voice; Bob stares open-mouthed.

In a few seconds, Three-phasing appears. He looks at Nine-hover for a moment, then scurries over to the Dawn couple and reaches up to touch Sarah on the left nipple. His body temperature is considerably higher than hers, and the unexpected warm moistness, as much as the suddenness of the motion, makes her jump back and squeal.

Three-phasing correctly classified both Dawn people as Caucasian, and so assumes that they speak some Indo-European language.

“GutenTagsprechensieDeutsch?” he says in a rapid soprano.

“Huh?” Bob says.

“Guten-Tag-sprechen-sie-Deutsch?” Three-phasing clears his throat and drops his voice down to the alto he uses to sing about the St. Louis woman. “Guten Tag,” he says, counting to a hundred between each word. “Sprechen sie Deutsch?”

“That’s Kraut,” says Bob, having grown up on jingoistic comic books. “Don’t tell me you’re a—”

Three-phasing analyzes the first five words and knows that Bob is an American from the period 1935-1955. “Yes, yes—and no, no—to wit, how very very clever of you to have identified this phrase as having come from the language of Prussia, Germany as you say; but I am, no, not a German person; at least, I no more belong to the German nationality than I do to any other, but I suppose that is not too clear and perhaps I should fully elucidate the particulars of your own situation at this, as you say, ‘time,’ and ‘place.’”

The last English-language author Three-phasing studied was Henry James.

“Huh?” Bob says again.

“Ah. I should simplify.” He thinks for a half-second, and drops his voice down another third. “Yeah, simple. Listen, Mac. First thing I gotta know’s whatcher name. Whatcher broad’s name.”

“Well … I’m Bob Graham. This is my wife, Sarah Graham.”

“Pleasta meetcha, Bob. Likewise, Sarah. Call me, uh …” The only twentieth-century language in which Three-phasing’s name makes sense is propositional calculus. “George. George Boole.

“I ’poligize for bumpin’ into ya, Sarah. That broad in the corner, she don’t know what a tit is, so I was just usin’ one of yours. Uh, lack of immediate culchural perspective, I shoulda knowed better.”

Sarah feels a little dizzy, shakes her head slowly. “That’s all right. I know you didn’t mean anything by it.”

“I’m dreaming,” Bob says. “Shouldn’t have—”

“No you aren’t,” says Three-phasing, adjusting his diction again. “You’re in the future. Almost a million years. Pardon me.” He scurries to the mover-transom, is gone for a second, reappears with a bedsheet, which he hands to Bob. “I’m sorry, we don’t wear clothing. This is the best I can do, for now.” The bedsheet is too small for Bob to wear the way Sarah is using the blanket. He folds it over and tucks it around his waist, in a kilt. “Why us?” he asks.

“You were taken at random. We’ve been time-casting”—he checks with Nine-hover—“for twenty-two years, and have never before caught a human being. Let alone two. You must have been in close contact with one another when you intersected the time-caster beam. I assume you were copulating.”

“No, we weren’t!” Sarah says indignantly.

“Ah, quite so.” Three-phasing doesn’t pursue the topic. He knows that humans of this culture were reticent about their sexual activity. But from their literature he knows they spent most of their “time” thinking about, arranging for, enjoying, and recovering from a variety of sexual contacts.

“Then that must be a time machine over there,” Bob says, indicating the fake console.

“In a sense, yes.” Three-phasing decides to be partly honest. “But the actual machine no longer exists. People did a lot of time-travelling about a quarter of a million years ago. Shuffled history around. Changed it back. The fact that the machine once existed, well, that enables us to use it, if you see what I mean.”

“Uh, no. I don’t.” Not with synapses limited to three degrees of freedom.

“Well, never mind. It’s not really important.” He senses the next question. “You will be going back … I don’t know exactly when. It depends on a lot of things. You see, time is like a rubber band.” No, it isn’t. “Or a spring.” No, it isn’t. “At any rate, within a few days, weeks at most, you will leave this present and return to the moment you were experiencing when the time-caster beam picked you up.”

“I’ve read stories like that,” Sarah says. “Will we remember the future, after we go back?”

“Probably not,” he says charitably. Not until your brains evolve. “But you can do us a great service.”

Bob shrugs. “Sure, long as we’re here. Anyhow, you did us a favor.” He puts his arm around Sarah. “I’ve gotta leave Sarah in a couple of days; don’t know for how long. So you’re giving us more time together.”

“Whether we remember it or not,” Sarah says.

“Good, fine. Come with me.” They follow Three-phasing to the mover-transom, where he takes their hands and transports them to his home. It is as unadorned as the time-caster room, except for bookshelves along one wall, and a low podium upon which the volume of Faust rests. All of the books are bound identically, in shiny metal with flat black letters along the spines.

Bob looks around. “Don’t you people ever sit down?”

“Oh,” Three-phasing says. “Thoughtless of me.” With his mind he shifts the room from utility mood to comfort mood. Intricate tapestries now hang on the walls; soft cushions that look like silk are strewn around in pleasant disorder. Chiming music, not quite discordant, hovers at the edge of audibility, and there is a faint odor of something like jasmine. The metal floor has become a kind of soft leather, and the room has somehow lost its corners.

“How did that happen?” Sarah asks.

“I don’t know.” Three-phasing tries to copy Bob’s shrug, but only manages a spasmodic jerk. “Can’t remember not being able to do it.”

Bob drops into a cushion and experimentally pushes at the floor with a finger. “What is it you want us to do?”

Trying to move slowly, Three-phasing lowers himself into a cushion and gestures at a nearby one, for Sarah. “It’s very simple, really. Your being here is most of it.

“We’re celebrating the millionth anniversary of the written word.” How to phrase it? “Everyone is interested in this anniversary, but … nobody reads any more.”

Bob nods sympathetically. “Never have time for it myself.”

“Yes, uh … you do know how to read, though?”

“He knows,” Sarah says. “He’s just lazy.”

“Well, yeah.” Bob shifts uncomfortably in the cushion.

“Sarah’s the one you want. I kind of, uh, prefer to listen to the radio.”

“I read all the time,” Sarah says with a little pride. “Mostly mysteries. But sometimes I read good books, too.”

“Good, good.” It was indeed fortunate to have found this pair, Three-phasing realizes. They had used the metal of the ancient books to “tune” the time-caster, so potential subjects were limited to those living some eighty years before and after 2012 A.D. Internal evidence in the books indicated that most of the Earth’s population was illiterate during this period.

“Allow me to explain. Any one of us can learn how to read. But to us it is like a code; an unnatural way of communicating. Because we are all natural telepaths. We can read each other’s minds from the age of one year.”

“Golly!” Sarah says. “Read minds?” And Three-phasing sees in her mind a fuzzy kind of longing, much of which is love for Bob and frustration that she knows him only imperfectly. He dips into Bob’s mind and finds things she is better off not knowing.

“That’s right. So what we want is for you to read some of these books, and allow us to go into your minds while you’re doing it. This way we will be able to recapture an experience that has been lost to the race for over a half-million years.”

“I don’t know,” Bob says slowly. “Will we have time for anything else? I mean, the world must be pretty strange. Like to see some of it.”

“Of course; sure. But the rest of the world is pretty much like my place here. Nobody goes outside any more. There isn’t any air.” He doesn’t want to tell them how the air was lost, which might disturb them, but they seem to accept that as part of the distant future.

“Uh, George.” Sarah is blushing. “We’d also like, uh, some time to ourselves. Without anybody … inside our minds.”

“Yes, I understand perfectly. You will have your own room, and plenty of time to yourselves.” Three-phasing neglects to say that there is no such thing as privacy in a telepathic society.

But sex is another thing they don’t have any more. They’re almost as curious about that as they are about books.

So the kindly men of the future gave Bob and Sarah Graham plenty of time to themselves: Bob and Sarah reciprocated. Through the Dawn couple’s eyes and brains, humanity shared again the visions of Fielding and Melville and Dickens and Shakespeare and almost a dozen others. And as for the 98% more, that they didn’t have time to read or that were in foreign languages—Three-phasing got the hang of it and would spend several millenia entertaining those who were amused by this central illusion of literature: that there could be order, that there could be beginnings and endings and logical workings-out in between; that you could count on the third act or the last chapter to tie things up. They knew how profound an illusion this was because each of them knew every other living human with an intimacy and accuracy far superior to that which even Shakespeare could bring to the study of even himself. And as for Sarah and as for Bob:

Anxiety can throw a person’s ovaries ’way off schedule. On that beach in California, Sarah was no more pregnant than Bob was. But up there in the future, some somatic tension finally built up to the breaking point, and an egg went sliding down the left Fallopian tube, to be met by a wiggling intruder approximately halfway; together they were the first manifestation of the organism that nine months later, or a million years earlier, would be christened Douglas MacArthur Graham.

This made a problem for time, or Time, which is neither like a rubber band nor like a spring; nor even like a river nor a carrier wave—but which, like all of these things, can be deformed by certain stresses. For instance, two people going into the future and three coming back, on the same time-casting beam.

In an earlier age, when time travel was more common, time-casters would have made sure that the baby, or at least its aborted embryo, would stay in the future when the mother returned to her present. Or they could arrange for the mother to stay in the future. But these subtleties had long been forgotten when Nine-hover relearned the dead art. So Sarah went back to her present with a hitch-hiker, an interloper, firmly imbedded in the lining of her womb. And its dim sense of life set up a kind of eddy in the flow of time, that Sarah had to share.

The mathematical explanation is subtle, and can’t be comprehended by those of us who synapse with fewer than four degrees of freedom. But the end effect is clear: Sarah had to experience all of her own life backwards, all the way back to that embrace on the beach. Some highlights were:

In 1992, slowly dying of cancer, in a mental hospital.

In 1979, seeing Bob finally succeed at suicide on the American Plan, not quite finishing his 9,527th bottle of liquor.

In 1970, having her only son returned in a sealed casket from a country she’d never heard of.

In the 1960’s, helplessly watching her son become more and more neurotic because of something that no one could name.

In 1953, Bob coming home with one foot, the other having been lost to frostbite; never having fired a shot in anger.

In 1952, the agonizing breech presentation.

Like her son, Sarah would remember no details of the backward voyage through her life. But the scars of it would haunt her forever.

They were kissing on the beach.

Sarah dropped the blanket and made a little noise. She started crying and slapped Bob as hard as she could, then ran on alone, up to the cabin.

Bob watched her progress up the hill with mixed feelings. He took a healthy slug from the bourbon bottle, to give him an excuse to wipe his own eyes.

He could go sit on the beach and finish the bottle; let her get over it by herself. Or he could go comfort her.

He tossed the bottle away, the gesture immediately making him feel stupid, and followed her. Later that night she apologized, saying she didn’t know what had gotten into her.