Chapter 8

Silent Spring, Noisy Spring

In November 1958, right in the middle of Rachel’s research into DDT and other pesticides, her mother had a stroke. Within a few days, Maria Carson died. Rachel was so sad that she stopped working. Her world wasn’t the same without her mother.

On top of that, Rachel seemed to have one illness after another. First she got the flu, then a bad stomach ulcer, and then arthritis. Rachel also suffered infections in her knees, which meant that she wasn’t able to go for walks along the seashore for months. In 1960, Rachel received even worse medical news: She was diagnosed with cancer. She was very sick. Would she ever be able to finish work on her project?

But Rachel knew that her work was important. The world needed to know about it, so she kept writing. She was often in pain and she was in and out of the hospital a lot. E

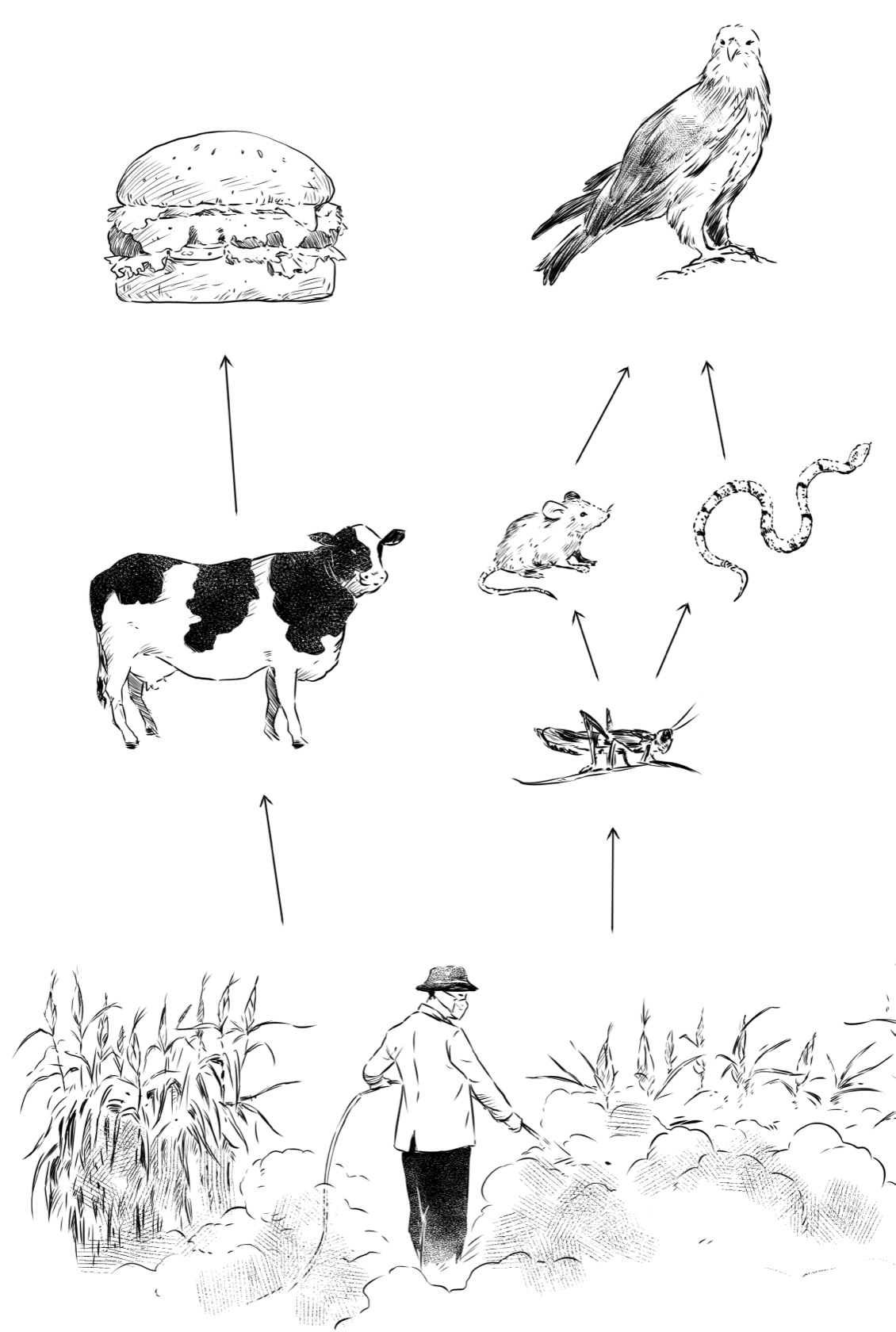

arly in 1962, Rachel’s latest book was ready. Rachel and her agent, Marie Rodell, discussed titles like The War Against Nature and At War with Nature. Although the subject of the book was serious, those titles sounded too harsh for Rachel’s poetic writing. Marie suggested Silent Spring as a title. Rachel had included a chapter in her book about how pollution and chemicals had an effect on birds, everything from sparrows to bald eagles. She had thought about using “Silent Spring” as the title for that chapter. But Rachel’s agent thought the title would work for the whole book. It would let people know that the future of the earth would be silent and sad if something wasn’t done to stop the use of pesticides and pollution.

Rachel had put a lot of hard work into her book. She had written and rewritten her words so that readers would understand the complicated scientific ideas. It had taken her over four years to complete Silent Spring. But would people read the book and see it as a warning? Would people listen and want to help change things?

Marie Rodell sent Silent Spring to Rachel’s publisher. She also sent it to The New Yorker magazine. A few days later, Rachel’s phone rang late at night. The editor of The New Yorker, William Shawn, had just finished reading the book. He called Rachel as soon as he finished it. He was shocked by the things Rachel had written about. How could the government allow big chemical companies to harm plants, animals, and humans? Was it too late to stop the damage?

Those words were music to Rachel’s ears. It was exactly the kind of reaction she wanted. And she hoped that everyone who read the book would have the same reaction. Mr. Shawn asked if he could run parts of Rachel’s book in his magazine before the book was published. Rachel said yes.

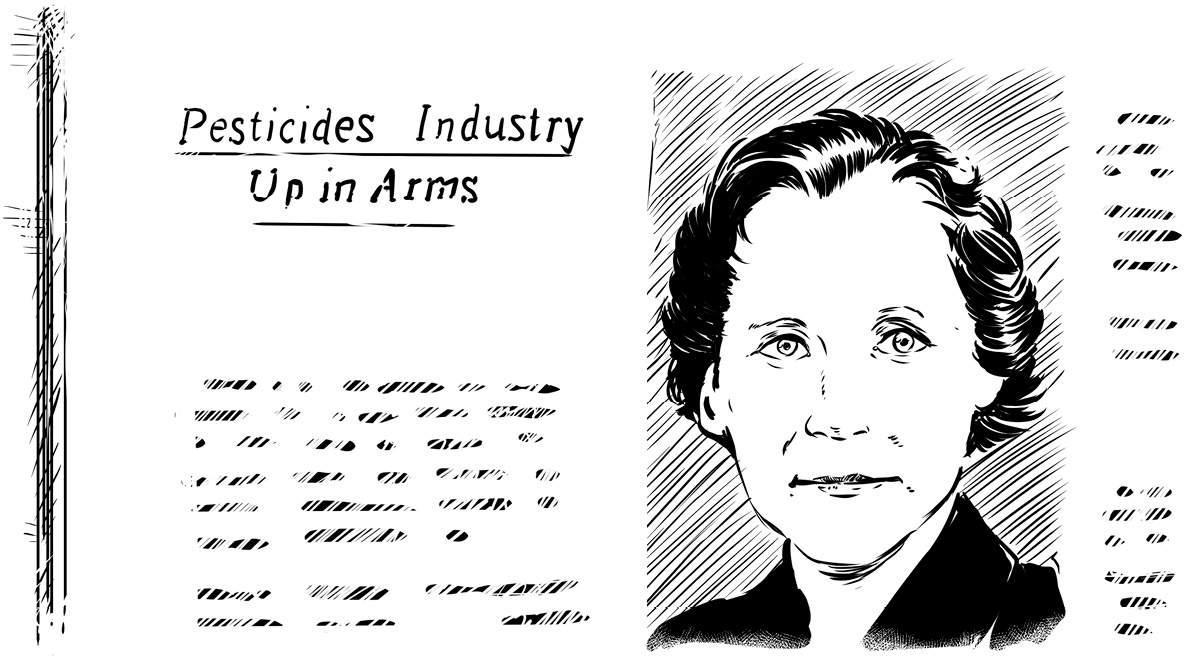

Although Rachel had received fan mail in the past, it was nothing like the amount she was receiving now. As soon as chapters of Silent Spring appeared in The New Yorker, letters started pouring in. People were shocked by what Rachel had to say. A few of the letters said that Rachel didn’t know what she was talking about. But most of the letters were very supportive. An article in The New York Times newspaper said that Rachel had written a story “few will read without a chill, no matter how hot the weather.” But Rachel and The New Yorker weren’t the only ones to get letters. Concerned and outraged readers also sent letters to newspapers, chemical companies, and the government.

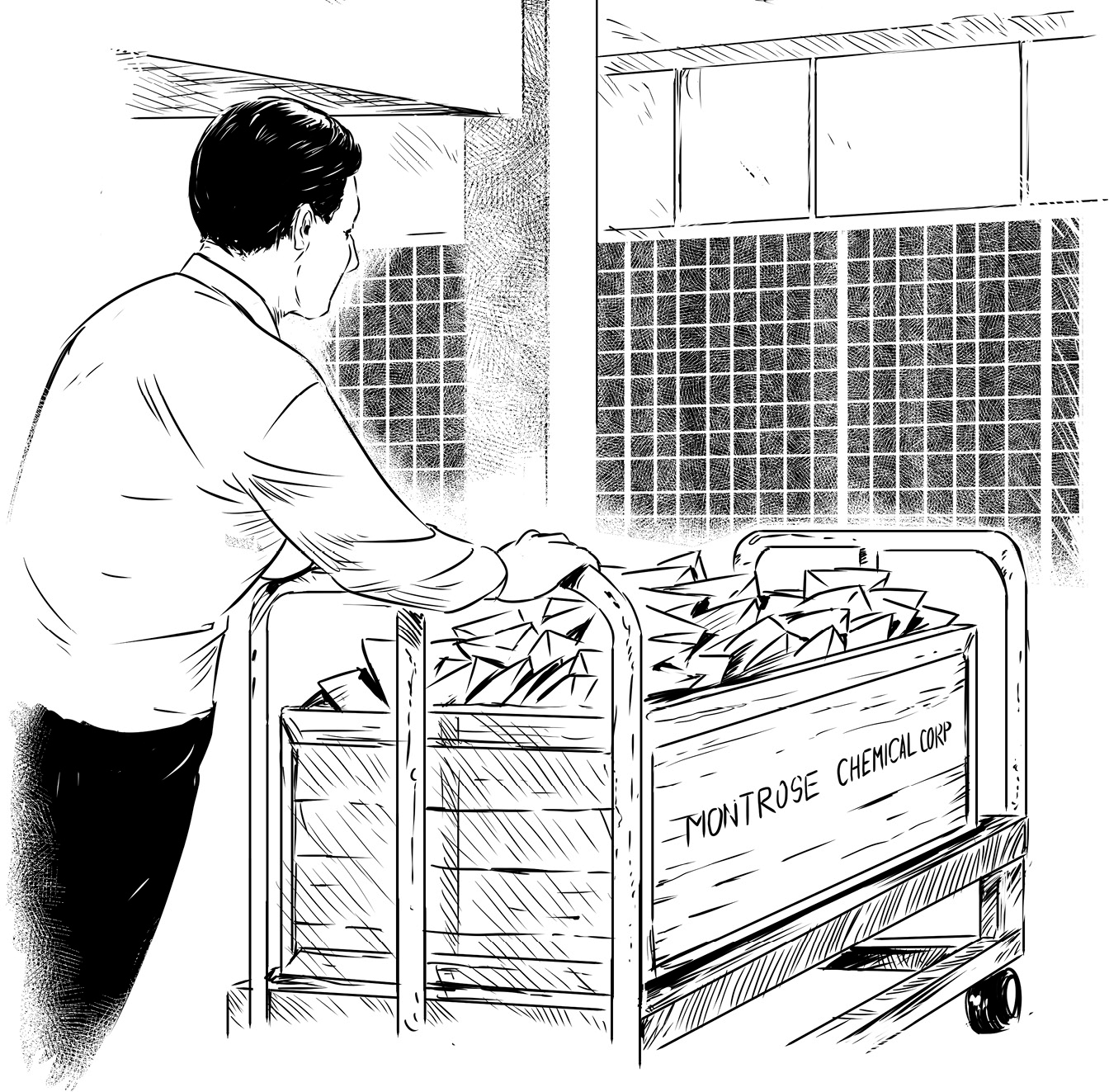

Representatives from the chemical companies and the Department of Agriculture weren’t happy with what Rachel had said in her book. They decided to fight back. They wrote newspaper and magazine articles and went on TV and the radio saying that Rachel had gotten her facts wrong.

But Rachel was sure that her research would stand up. She had always worked hard to make sure that whatever she wrote was true. And Rachel didn’t want to completely ban the use of pesticides. She just wanted people to learn more about them and to understand that they had an effect on the total environment—everything found in nature could be harmed by pesticides. Rachel wanted the government and the chemical companies to make sure they tested the chemicals before they used and sold them.