Following the encirclement and destruction of Axis forces at Stalingrad, Soviet forces spent the next two years conducting an inexorable strategic advance that recaptured all of their lost territory, and continued beyond their pre-1939 borders into Eastern Europe. Supplied with substantial Lend/Lease logistical assets, especially badly needed transport, the Red Army were frequently able to concentrate overwhelming numbers of men and machines at sectors and times of their choosing. Their effective use of maskiróvka (“deceptive measures”) and a growing level of operational experience meant that the Germans were often forced to react to an unexpected or unfavorable situation. With Soviet forces seemingly in strength everywhere along the front German command and control could not consistently or effectively prioritize and address threats and their combat formations were frequently forced to withdraw or risk destruction.

During the summer of 1944 this scenario occurred on a grand scale where the Soviet Bagration offensive virtually annihilated Army Group Center. Hitler’s belief that the Red Army would try to use their recent acquisition of the western Ukraine as a springboard from which to attack into Romania, Hungary, and southern Poland prompted him to reposition much of his armor south to contest such a move. Instead, the Soviets launched a devastating offensive further north that drove a massive wedge into Belorussia. Unable to regain their strategic balance following Stalingrad and Kursk, the Ostheer (“East Army”) traded space for time, while they tried to re-establish adequate defenses and solidify the front. To compound their difficulties, Hitler continually interfered with the war’s conduct and the actions of experienced commanders on the spot. By acting as both Supreme Commander and head of the OKH (Army High Command, in charge of the Eastern Front), his authority was unencumbered by other opinions, with predictably disastrous battlefield results. Had the German General Staff been employed as the primary military decision-making entity for which it was established, such a desperate situation might well have been avoided.

Hitler, continuing to rely heavily on intuition, believed that the Soviets’ next great offensive would be against his East Prussian and Hungarian flanks. The head of Fremde Heere Ost (Foreign Armies – East), Generalmajor Reinhard Gehlen, disagreed. His position within Army Intelligence overwhelmingly indicated that the Red Army would instead attempt to capture Berlin and much of central Europe before the western Allies were in a position to contest it. This seemingly indisputable evidence on Red Army dispositions and intentions was passed to Army Chief of Staff Generaloberst Heinz Guderian, and then to Hitler who promptly refuted the assessment. Although outwardly Hitler expressed his belief that the battlefield situation was a Soviet ruse, in fact the Führer’s longstanding dislike of Gehlen’s direct manner and pessimistic view of Germany’s present ability to offer effective resistance meant the findings were not acted upon. As a consequence, Marshal Georgy Zhukov’s 1st Belorussian and Marshal Ivan Konev’s 1st Ukrainian Fronts were able to capitalize on their achievement against far less opposition than would have otherwise been possible. In mid-January 1945 the pair were able to quickly overrun Poland and establish several small bridgeheads across the Oder River from near Stargard to south of Breslau.

To help stem the flood of Soviet forces moving across Poland, Guderian proposed the creation of an emergency army group to bolster the much weakened Army Group Center (soon renamed Army Group North). On January 24, Hitler gave his approval, but instead of an experienced commander, he assigned Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler to the task, proclaiming that his long-time henchman’s exceptional skills at administration and motivation would soon stabilize the situation. In addition to being the head of all branches of the Schutzstaffel (SS), including the Waffen-SS, Himmler had also been put in charge of the Replacement Army following the attempted July 20, 1944 assassination of Hitler by members of the Army. In principle this gave him discretion over where to allocate such manpower resources, often for political rather than military reasons. Himmler’s recent performance as commander of Upper Rhine High Command, an independent theater-level formation answering directly to Hitler, and its ill-conceived operation against French and US forces around Colmar instilled little confidence in the experienced senior officers who were aware of the impending operation.

A crewman working with a “broken-nose,” narrow-mantlet IS-2’s muzzle-brake cover. Such protection would be used in transport to keep dust and debris from entering the barrel. Note the female soldier atop the turret. (DML)

In preparation for the counterattack from east of Stargard German reinforcements were soon moving through Stettin to create the new Army Group Weichsel (Vistula). Among these, III (Germanic) SS Panzer Corps was steadily pulled from the isolated front on the Courland Peninsula (Latvia), organized at the Hammerstein Training Area southwest of Danzig, and sent to Himmler to act as his command’s linchpin. Instead of deploying his forces across the most direct route to Berlin, however, the Reichsführer-SS arrayed the various subordinated replacement and recently separated units in parallel to the Baltic coast in an effort to defend the whole of Pomerania. Zhukov, confident in his superiority of 3:1 in infantry and 5:1 in armor and artillery, simply ignored what he believed to be a “phantom” force, and continued to focus westward toward the German capital.

As Konev approached the Oder, Zhukov’s forces encircled the city of Posen on January 24. As Posen was a major transportation hub, the resulting German defense presented a considerable disruption to Soviet logistics between Warsaw and Berlin. As with other Hitler-designated Festungen (fortresses) the city was expected to be held at all costs, in part to draw large numbers of the enemy into static, attritional battles that favored the defender. To encourage German efforts to defend the homeland to the fullest, civilians were often ordered to remain in forward areas at risk of being overrun. As soldiers fought for these “live” cities, all knew the dangers of surrendering to the Red Army, with its widespread list of atrocities against not only Germans, but Poles, Hungarians, freed POWs, and others. Compounding the atmosphere of terror, fever-pitch propaganda spewed from both sides calling for a fight to the death, while behind the German lines Feldjägerkorps, overzealous Hitler Youth, and other groups roamed the rear areas to summarily execute anyone not carrying official documentation granting them permission to be away from the combat zone.

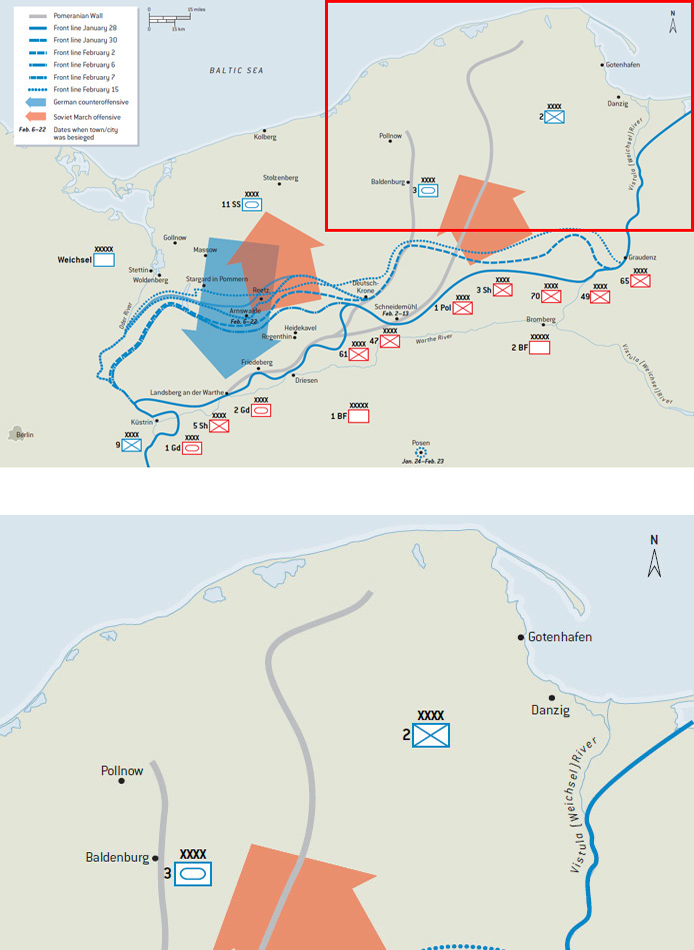

An operational view of the fighting in Pomerania following the Soviet Vistula–Oder Offensive, January 28–February 15, 1945.

Overturned T-34 Model 1941s that were probably caught by artillery or an air-to-ground attack. What looks to be the explosion’s by-product is now a water-filled shell hole. (DML)

On January 27 lead Soviet armored units crossed the Draga River at Neuwedell, and appeared to herald the imminent collapse of the Pomeranian front. German forces erected makeshift barricades at important crossroads, and scrambled to establish defensive positions with ad hoc, predominantly infantry forces possessing few heavy weapons. Even supply and “non-essential” personnel were thrust into front-line duty, which did little except further disrupt German logistics. Others assisted the flood of westward-fleeing refugees attempting to stay ahead of the advancing Soviets, and reach relative safety beyond the Oder and Elbe rivers. Public officials, motivated to save lives, often permitted populated areas to be evacuated, against orders from the regional Gauleiter or higher authorities. As the front line receded toward towns like Arnswalde, Reetz, and Stettin residents tried to help the passing refugees, but sandwiches and coffee were small comfort to those who had recently lost everything save what could be carried personally or transported on carts. Trucks and trains that were available removed what civilians they could, but as the latter had to burn on low-quality coal substitutes such as lignite their operating effectiveness was reduced by as much as 60 percent. When the Red Army cut the direct routes between Deutsch Krone and Stargard on February 4, such operations through the Arnswalde area largely ceased.

A T-34 Model 1941/42 being shelled by artillery. (NARA)

Much as had happened to the western Allies following their breakout from Normandy, the speed and magnitude of the Vistula–Oder operation had placed a considerable strain on Soviet logistics. Second Guards Tank Army, for example, started out from the Vistula with 838 tanks and self-propelled guns. After advancing an average of 40km per day, when Colonel-General Semyon Bogdanov’s command reached the Oder in early February its infantry and armor forces were reduced by a third. Unlike the Germans the Soviets were increasingly well supplied as production and transportation services substantially grew during the last half of 1944. Guns larger than 76mm, heavy armor, and aircraft production were a priority, but getting these resources to where they were needed was another matter, especially ammunition and petrol, oil, and lubricants (POL). As the withdrawing Germans practiced a scorched earth policy of destroying and denying as much as possible to the pursuing Soviets, the latter needed to create infrastructures from scratch as they advanced.

With German defenses presently disorganized and undermanned, Soviet commanders deliberated on whether to press immediately for Berlin or to wait for their supply chain to catch up. The latter would allow the enemy time to solidify their own position. On the other hand, to push immediately beyond the Oder invited disaster as Zhukov’s First and Second Guards Tank Army spearheads would be vulnerable to encirclement; similar events, such as the failure of the Red Army’s headlong advance after Stalingrad, which was pinched off and shattered by Generalfeldmarschall Erich von Manstein, or the sudden defeat of Russian forces at Warsaw in 1920, seemed to justify these concerns.

On January 26 and 27, Zhukov and Konev respectively submitted plans to the Stavka (Soviet High Command) for the encirclement of the German capital. Zhukov proposed to take Berlin in a coup de main beginning around February 1, while his peer favored pushing past Breslau to act as a southern pincer in which both fronts would surround the German capital. With Stalin siding with Konev’s option, Soviet forces were hurriedly reorganized in preparation for offensive action west of the Oder River slated for between February 4 and 8, with Berlin’s capture to follow on the 15th. In the interim Zhukov determined that the Germans would make a stand along the Schwedt–Stargard–Neustettin line to defend Stettin and the Pomeranian coast, while additional forces would probably deploy east of Berlin to defend the direct route to the city. To address these perceived eventualities he sent Fifth Shock, Eighth Guards, Sixty-Ninth and Thirty-Third Armies west to secure bridgeheads over the Oder. The remaining First Polish, Forty-Seventh, Sixty-First, and Second Guards Tank Armies were positioned along the Falkenburg–Stargard–Altdamm–Oder River line to cover Zhukov’s northern flank.

General der Panzertruppen Heinz Guderian, commander of XIX Corps, in France in 1940 (note his officer’s sword pommel). His chief of staff, Oberst Walter Nehring, follows; his Iron Cross clasp, indicating that he earned the award during World War I, is attached to the chest ribbon. (DML)

Neither Sixty-First Army’s advance toward Arnswalde nor Rokossovsky’s combat-depleted 2nd Belorussian Front before Danzig was able to advance quickly due to enemy resistance. This resulted in a 100km gap between the two groups, which Zhukov moved to plug. On February 1 Zhukov issued Order No. 00214, which disengaged Second Guards Tank Army from combat along the Oder in order to rest, replenish, and form a northward-facing reserve between Landsberg and Schneidemühl. Other Soviet armored units between Küstrin and the Neisse River were similarly trading positions with infantry, so as to be fresh when they would once again spearhead the coming Soviet ground offensive against Berlin.

Lieutenant-Colonel Peter Mzhachih, commander of the 88th Guards Heavy Tank Regiment, near Küstrin in early spring 1945. His awards include the Orders of the Red Star, Great Patriotic War (both classes), and Red Banner. (Courtesy Mikhail Zharkoy)

By early February the very cold winter weather of the previous several weeks had given way to intermittently warmer temperatures. Although sleet and freezing rain remained the resulting thaw hampered movement and the Red Army’s ability to establish forward air bases from which to support the ground forces. The Oder River had correspondingly flooded to a width of up to 6km, and although the Soviets possessed the resources to effect crossings the added prospect of strong German resistance made it inadvisable at present. On February 5, Sixty-First Army struggled to plug the gap on Zhukov’s right as a general lack of fuel meant that what was available was allocated to combat and staff vehicles only. When Konev broke out of his Oder bridgehead three days later, the Germans needed to present an effective response, as ever-smaller territory was available in which to withdraw.

With all the military setbacks Germany had suffered over the last two years, their increasingly short supply lines, and effective resource management by Albert Speer and others, permitted their rapid reaction to the faltering Eastern Front. Between January 20 and February 12 the Kriegsmarine (German Navy) and hundreds of transport ships, as part of Operation Hannibal, had evacuated some 374,000 refugees and thousands of wounded soldiers from sectors cornered against the Baltic Sea and threatened with annihilation. Salvaged combat formations were redirected to Pomerania’s defense to contest what was believed to be an impending thrust by Second Guards Tank Army to capture the area around Kolberg on the Baltic coast. Should the German Second Army become isolated from the rest of Army Group Weichsel, the Soviets would unhinge German efforts to protect the province and split east toward Danzig and west for Stettin.

In early February, Guderian looked for a way to pinch off the Soviet spearheads that had advanced to the Oder River before follow-on forces could strengthen the positions. The German bridgehead at Küstrin, and Sixth SS Panzer Army further south, presented resources to launch the right hook coinciding with a similar attack from around Stargard. Should such a limited two-pronged counterattack linking up around Landsberg prove successful, Zhukov’s westward advance would be temporarily stymied, and the resulting time could be used to strengthen Berlin’s defenses and possibly to secure an armistice. As additional forces would be needed for such an endeavor, Guderian lobbied for the reallocation of formations from sectors he felt no longer contributed to the war effort, such as at Courland, Italy, Norway, and the Balkans, to what should have been the primary endeavor to protect Berlin. The Führer, however, would have none of it. Sixth SS Panzer Army, recently released from fighting in the Ardennes on the Western Front, had been sent to Hungary to try to retain the region’s oil facilities. With hopes for a two-pronged operation quashed, Guderian settled on assembling the remaining northern force to attempt a more modest operation.

A tactical view of the start of Operation Sonnenwende showing two days of German progress following their jump-off on February 15, and the areas of Soviet resistance.

While German ground forces adjusted to new positions along the Oder and Neisse rivers the Luftwaffe was responding similarly. The Air Fleet in charge of the area, Luftflotte 6, had expanded from 364 aircraft on January 6 to some 1,838 fighters, bombers, transports, and reconnaissance planes by February 3. Overflights east of the Oder had also increased, with 2,409 on February 1, 1,805 on the 2nd, and 1,995 on the 3rd, as had air-to-ground action. Although Guderian hoped his strongest asset would be surprise, Zhukov did not need his VNOS (aerial reconnaissance, warning, and communication service) to know that the increase in enemy air traffic indicated that a German counterattack was in the offing. Unsure of the time and direction, he continued to reposition his forces and prepared for such an event as best he could.

Considering the chaotic German military situation in 1945, Guderian was able to assemble a surprisingly large force consisting of three and a half divisions from Third Panzer Army (recently evacuated from near Königsberg) and two re-formed Panzer divisions. In accordance with Hitler’s order that this gathering force was to be entirely Waffen-SS, SS-Obergruppenführer Felix Steiner was put in charge of the hastily organized, corps-sized Eleventh SS Panzer Army. As a former select member of the prewar Reichswehr, and an experienced battlefield commander of such multinational forces as 5th SS Panzergrenadier Division Wiking, Steiner seemed to be the natural selection for such a daring, late-war endeavor.

On February 8, Stalin abruptly canceled the impending offensive against Berlin, and instead ordered that Rokossovsky’s 2nd Belorussian Front first clear Pomerania. Although logistical problems and encircled enemy “fortresses” presented temporary problems, Stalin was motivated by political considerations as well. The western Allies had been held west of the Roer River and the Westwall (Siegfried Line to the Allies) for the last six weeks as Hitler’s long-sought-after counteroffensive in the Ardennes ran its inevitable course. Eisenhower’s forces were only now renewing their eastward drive into Germany and would not come near those territories that Stalin coveted, but did not yet control, for some time.

After eight days of stockpiling food, fuel, and ammunition for Guderian’s counterattack, by February 10 less than half of the estimated requirements had been obtained. With the attack scheduled for the 22nd, Third Panzer Army were not likely to arrive in time to participate. Eleventh SS Panzer Army, with their subordinate XXXIX Panzer, III (Germanic) SS Panzer, and X SS Corps, would be all that was available for carrying out the overly optimistic mission of fighting through the Soviet Sixty-First Army and advancing on to the Küstrin–Landsberg area to cut off Second Guards Tank Army spearheads. Even as Steiner’s force accumulated reinforcements, many had to be quickly returned to combat to prevent Soviet penetrations of the front line and preserve his assembly positions.

During a conference with Hitler on February 13, Guderian proposed that as Rokossovsky’s 2nd Belorussian Front was now threatening to cut off Danzig, Eleventh SS Panzer Army needed to go over to the offensive in two days to divert Soviet attention and resources. Hitler and Himmler were reluctant to start such an operation until sufficient supplies were gathered, but Guderian managed to secure approval for an amended start date. To gain a measure of operational control, and provide the greatest chance for success, he had his young – but very skilled and experienced – protégé, Generalleutnant Walther Wenck, allocated to command the operation, which was codenamed Husarenritt (“Hussar ride”), later changed to Sonnenwende (“Solstice”).