When the 57-tonne Tiger I tank first entered German service on the Eastern Front in August 1942, it was made even more formidable as an individual battlefield weapon by being grouped into independent heavy armor battalions of up to 45 vehicles. Originally intended to add an offensive, heavy-combat element during German breakthroughs, after mid-1943 these formations were increasingly used in defensive “fire brigade” or mobile reserve roles to help shore up threatened sectors. With exceptions made for research, training, and allocation as company-sized complements to select Army and Waffen-SS divisions, Tiger I and II units were subordinated to corps and army-level commands. Throughout the war, ten heavy Panzer battalions were created for the Army, which operated in North Africa, Italy, northwest Europe, and the Eastern Front. After April 1943 four more were to be organized for the Waffen-SS, with three coming to fruition as 101st, 102nd, and 103rd Heavy SS Panzer Battalions serving under I, II, and III (Germanic) SS Panzer Corps, respectively.

Initially, heavy Panzer battalions officially comprised 20 Tiger Is and 16 Panzer IIIs that were organized into two armored companies, each of four platoons; two of each vehicle were allocated per platoon, plus a Tiger I for each company commander, and a pair for battalion command. As Tiger I and II production increased, the “medium” vehicles were eliminated from the roster. On November 1, 1944, the heavy Panzer battalion received its final company TO&E (KStN) designations: 1107 (fG) (Staff); 1176 (fG) (Armor); 1151b (fG) (Supply); and 1187b (Maintenance).

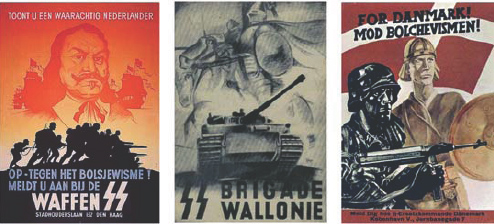

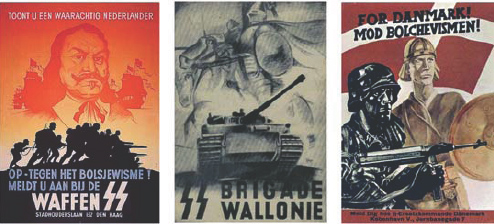

Recruiting posters in German-occupied areas sought to promote the idea of a unified European effort to resist Communist Russia. Historical figures or cultural elements were often used to tie the present struggle to some noble past endeavor. (Public domain)

As with the German Army, Waffen-SS inductees first went through several months of intensive infantry basic training; this was so rigorous that in the early part of the war one-third did not finish. Physical fitness, small-arms skill, and political indoctrination were especially stressed. Upon completion of initial instruction individuals could apply for specialized training, for example as officer candidates or engineers, or for service in the armor branch. For the role of tanker those with mechanical or technical skills were naturally most in demand, with training conducted at one of several armor facilities throughout the Reich. Although each crewman was to become familiar with each other’s duties, the need for strong interaction among the commander, loader, and gunner was particularly stressed, as close cooperation among this trio translated into rapid responses to battlefield threats.

Because the Tiger II was seldom used at battalion strength, Tiger II platoons (each made up of four plus a command vehicle) performed assaults in one of two manners. A “Caterpillar” advance (left) attempted to combine the firepower of all the vehicles in the platoon by moving two-vehicle sections in parallel before joining up at a selected point. During a “Leapfrog” advance (right) the platoon was again divided into a pair of two-vehicle sections, with one section providing support as the other moved forward. While the “Leapfrog” tactic was harder to control, it made for a quicker advance. The command vehicle would maneuver through each formation in order to coordinate movement and interact with any supporting units.

Actual armor strengths are underlined as xx; TO&E/KStN values for armor and manpower are not

Commander: SS-Sturmbannführer Friedrich (Fritz) Herzig

Total strength: 45/39 (832 men)

Staff & Staff Company (171 men)

Group Leader: 3/1

Reconnaissance, Engineer, Antiaircraft Platoons

1st Panzer Company: 14/13 (87 men)

Group Leader: 2/1 (17 men)

1st, 2nd, 3rd Platoons: 4 each (60 men in total)

Change crew (10 men)

2nd Panzer Company: 14/13 (87 men)

Company HQ: 2/1 (17 men)

1st, 2nd, 3rd Platoons: 4 each (60 men in total)

Change crew (10 men)

3rd Panzer Company: 14/12 (87 men)

Company HQ: 2/1 (17 men)

1st, 2nd Platoons: 4 each, 3rd Platoon: 3 (55 men in total)

Change crew (10 men)

Supply Company (258 men)

Group Leader, Damage Clearance and Repair Services

Medical, Fuel, Munitions, Administration Sections

Workshop Company (142 men)

Group Leader, Workshop, Recovery Group, Armory, Signal Equipment Workshop, Spare Parts Group, Supply Train

Because officer candidates and enlisted personnel trained together the sense of comradeship between the two groups was correspondingly strengthened. Where the Army instilled a distinct separation between officers and the lower ranks, the Waffen-SS promoted mutual respect, and a more relaxed atmosphere in which officers were simply addressed by their rank without the traditional “Herr” prefix. After 1943 foreign volunteers (preferably Nordic, but also non-Germanic) joined in increasing numbers, in part to fight against what was seen as a Communist threat against European civilization. Although Hitler desired to incorporate these elements into the whole to instill the concept of a united “Germania,” Swedes, Norwegians, Dutch, French, and others were organized according to nationality.

Tiger II crews focused on achieving surprise and executing decisions quickly. Once fields of fire were established, terrain was to be exploited for protection and concealment. Enemy armor and antitank guns were priority targets, and against overwhelming numbers the tankers were to scatter and regroup to a more advantageous position. On spotting hostile tanks, the Tiger II was to halt and get ready to engage them by surprise, estimating the enemy’s reaction before launching an attack. The crew should hold fire as long as possible, and, if possible, the enemy tanks should not be engaged by a single tank so as to apply maximum firepower.

As Germany’s manpower pool, resources, and leverage to achieve any sense of a negotiated peace dwindled, 503rd Heavy SS Panzer Battalion, like other armored formations, was increasingly forced to train on obsolete foreign and domestic tanks. More modern vehicles such as the Tiger I were needed at the front and the battalion’s complement correspondingly dwindled. The Tigerfibel (the Tiger I manual, which was also applicable to the Tiger II), defined several guidelines for the vehicle’s official operation and deployment within a heavy armor battalion. In practice, however, deviations were unavoidable, and at the commander’s discretion. To facilitate these, emphasis was laid on the importance of rapid communications between the battalion and its parent command, as such formations required as much time as possible in which to get organized and allocated to a threatened sector. There was also a heavy reliance on armored engineers to strengthen bridges and clear minefields ahead of the heavy tanks.

Panzerwaffe doctrine stressed offensive almost to the exclusion of defensive combat, as evidenced by the 1941 Army Service Regulation Heeres-Dienstvorschrift 470/7 (regarding medium Panzer companies), and similar Army Regulations. At most the latter was considered applicable for ambush and a position from which to counterattack. Armor regiments and battalions were doctrinally to employ one of three offensive actions. Firstly, in a Vorbut (meeting engagement), an advance force, generally at least company-sized, was employed for taking an enemy by surprise so as to gain key terrain or a similar objective. Alternatively, Sofortangriffe (quick attacks), often conducted using the Breitkeil (broad wedge) formation (a reverse wedge with two platoons forward and the remaining platoon providing flank support as required) were used when supporting forces were not readily available and immediate action was needed. Finally, an Angriff nach Vorbereitung (deliberate attack) could be conducted as a complete unit against prepared defenses.

As a result of the German Army’s effective training and discipline, commanders were generally given a considerable degree of flexibility in carrying out tactical and small unit operations. Given little more than the mission and the leader’s intention, commanders could conduct an operation, while adjusting to battlefield situations as they occurred. This was perhaps best exemplified in the Panzerwaffe where timely intelligence, security, march discipline, and communications were especially important elements in achieving victory on the battlefield.

When the Tiger I made its combat debut in November 1942 its battlefield tactics and the operations of heavy armor battalions were largely improvised by the crewmen based on their personal experiences. By the time the Tiger II was first fielded in early 1944, a more established doctrine had been developed to address specific battlefield eventualities in a unified manner. Officially, four-vehicle armor platoons were to deploy in either a Linie (line) (section leader/vehicle/platoon leader), a Reihe (row) (platoon leader/vehicle followed by section leader/vehicle), a Doppelreihe (double row), or a Keil (wedge), but in practice terrain, the situation, and the commander’s experience meant these “parade” formations were seldom used.

On April 15, 1943, III (Germanic) SS Panzer Corps was formed to organize 5th SS Panzergrenadier Division Wiking and 11th SS Volunteer Panzergrenadier Division Nordland. Ten weeks later Nordland’s 11th SS Panzer Regiment (two battalions) completed Tiger I training at Grafenwöhr (southwest of Berlin), and for the next three months it served in an infantry capacity, taking part in its corps’ anti-partisan operations in Croatia and in the disarming of Italian forces following Italy’s surrender in September. On November 1, 1943, II Battalion, 11th SS Panzer Regiment, was re-designated 103rd Heavy SS Panzer Battalion, and was soon sent to the training grounds at Wezep in the Netherlands, and later to Paderborn in northwest Germany. Just prior to the Normandy invasion in mid-1944 the battalion was ordered to transfer its trained crews to 101st and 102nd Heavy SS Panzer Battalions as they would soon be fighting in the region. For the next few months the men of 103rd Heavy SS Panzer Battalion (re-designated 503rd Heavy SS Panzer Battalion on November 14, 1944) trained a new batch of crews, which after October 19, 1944, were allocated Tiger IIs.

Like other nations, during the 1930s the Soviets attempted to find the most effective organizational balance for their light, medium, and heavy tanks. Cooperation with the German Reichswehr, and combat experience gained at Khalkin Gol and Poland (1939), Finland (1939–40), and elsewhere, led to a reconsideration of fielding large mixed corps formations comprised of a variety of tank types and weights. They were simply too large and awkward for most of their commanders to control effectively, and unnecessarily taxed logistics. To address the inconsistency of vehicle types, the well-balanced and maneuverable T-34s were organized as homogeneous tank brigades. The heavily armed and armored “breakthrough” tanks such as the KV-1 were hamstrung by weight and mechanical unreliability, and could not keep pace with their medium brethren. Consequently, these vehicles were structured as independent, direct infantry support tank regiments.

In February 1944 the Red Army began re-equipping their heavy tank regiments with IS-2s and giving such units the designation of “Guards,” which was based on such units’ weapons and role, rather than any outstanding previous performance. The KV-1s, KV-85s, and British Lend/Lease Churchills were phased out, being outdated and generally unsuited for breakthrough roles, and having suffered high losses in combat. Where the T-34 was to retain its role of exploiting offensive penetrations by quickly moving into the enemy’s flanks and rear, as per Soviet deep penetration doctrine, the IS-2 units were to create the initial opening in enemy lines. In this capacity, they were to capture and hold key locations such as road intersections and river crossings until larger forces moved up, at which time they would either continue to the next objective or return to reserve status for any maintenance, etc.

A US Army collection point showcasing a variety of weapons including an IS-2 barrel and mantlet (with damage around the TSh-17 telescope’s viewport), and BR-471 antitank round. The table displays a pair of two-piece US M20 3.5in rocket launchers (“Super Bazookas”), several 88mm guns, and what looks to be a 37mm FlaK 43 antiaircraft gun. (DML)

Majors from 88th Guards Heavy Tank Regiment stand with their commanding officer (Mzhachih, third from left) near Küstrin in early spring 1945. The IS-2 pictured was one of only two that remained following heavy losses incurred since starting from the Vistula River. Note the shapka-ushanka lambswool hats. (Courtesy Mikhail Zharkoy)

Of the war’s 123 named Guards heavy tank regiments, 58 possessed IS-2s. The remainder retained different heavy tanks such as the KV-1, were disbanded, or were reconstituted. Nine Guards heavy tank brigades were subsequently re-fitted with IS-2 regiments. In practice the component regiments were often sent into action separately, and paired with self-propelled guns that moved alongside infantry to subdue stubborn enemy defenses.

During the initial period of the Russo-German War the Red Army had suffered catastrophic materiel and personnel losses, a problem compounded by Stalin’s prewar purges of some 43,000 members of the officer corps. New formations had to be created without the guidance of adequately experienced armor commanders, and this resulted in an incomplete and all-too-brief training regimen. As the commanders who remained feared failure as a consequence of deviating from established doctrine, creativity and initiative were replaced with an inflexible adherence to orders and institutionally optimal solutions to battlefield situations. This rigid approach to training, while often aiding rapid combat responses by junior officers, proved ineffective when encountering unforeseen situations.

Where the two-man turrets of the T-34 and KV-1 forced the commander to double as loader, the IS-2 had enough internal space for a more effective trio. The “Iosef Stalin” was assigned two officers (commander and driver), and two sergeants (gunner and loader/mechanic). Because of the dangerous missions these heavy tank forces would undertake, the additional officer was seen as a way to provide command redundancy, and lessen the chances of the crew shirking from their assigned duties.

Boris Eremeev was born to a peasant family on December 23, 1903, in the western Ukrainian village of Mykhalkove. At age 21 he graduated from the Uman Vocational and Technical School and applied his training toward agriculture before being drafted into the Red Army in 1925. Three years later Eremeev graduated from the Frunze Military Academy, essentially a staff college/ graduate school, and joined the Communist Party as an official prerequisite for his new command rank and position.

During the Great Patriotic War Major Eremeev initially served as Chief of Staff for 33rd Tank Regiment. Following the German summer offensive in 1942, he was made Chief of Staff for XVIII Tank Corps between July 7 and September 20, 1942, north of Stalingrad, and during the city’s encirclement three months later. As a slightly weaker equivalent to a contemporary German armor division, the tank corps’ mix of engineer, motorized infantry, antiaircraft, and roughly 150 KV-1s, T-34s, and T-70s translated into a nimble, all-arms formation that was better able to weather combat than its 1941 predecessors. On February 22, 1943, Eremeev was promoted to command XVIII Tank Corps’ 107th Tank Brigade, which was nearly destroyed during Manstein’s counteroffensive.

During Operation Citadel, Eremeev served as Chief of Staff for XXX “Urals Volunteer” Tank Corps between March 18 and September 21, 1943. He then commanded 244th Tank Brigade Chelyabinsk until October 23, 1943, and for another four months after it was converted into 63rd Guards Tank Brigade Chelyabinsk. On March 28, 1944, Eremeev was given command of 11th Guards Heavy Tank Brigade, a post he would hold until one day after the official end of the war in Europe in 1945. Eremeev went on to win the Order of the Red Banner for helping to eliminate German defences at Kovno, and later the Order of Lenin. On May 31, 1945, he was presented the Gold Star Medal of the Hero of the Soviet Union for his efforts during the Battle of Berlin. Made a Major General of Tank Troops six weeks later, Eremeev graduated from the Higher Academic Courses of the General Staff Military Academy in 1948, and served for the next nine years until his retirement. He died in Kiev on March 21, 1995.

Boris Romanovich Eremeev, commander of 11th Guards Heavy Tank Brigade. A colonel at the time of Sonnenwende, he is shown here with his postwar rank of major general of tank troops. Above the various commemorative and campaign decorations hangs the Gold Star Medal of the Hero of the Soviet Union. (Courtesy Igor Serdukov)

IS-2 officers, having passed through one of the country’s tank academies at Ulyanovsk, Saratov, Gorky, and elsewhere, would train on the IS-2 either with 1st Guards Tank or at the Chelyabinsk or Salikamsk Tank Academies. Starting in May 1943, this year-long course (often just eight months) produced second lieutenants. Higher regimental and brigade officers could attend the J. V. Stalin Academy of the WPRA Mechanization and Motorization Program, which, along with promotion, brought increasing privileges as part of the officer corps.

NCOs received roughly three months of training that comprised specialized class work and training on the IS-2, focusing on loading, aiming, and firing the main gun, ammunition care, radio operation, and technical and mechanical skills. At Chelyabinsk 30th and 33rd Tank Regiments had been allocated for applying tactical procedures, negotiating a variety of natural and constructed terrain types and obstructions, and, about a third of the time, performing night maneuvers, as well as undergoing driver training (all too short). Most of the cadets possessed little, if any, armored combat experience. For the final stage of training, crews were sent to 7th Training Armored Brigade at Chelyabinsk for regimental and brigade instruction, where following the usual send-off fanfare acknowledging the responsible factory workers, newly produced IS-2s were allocated to their new owners.

Soviet armored tactics were inspired by actions such as the 1916 Brusilov Offensive during World War I (1914–18), and later the Russian Civil War (1917–21) and Russo-Polish War (1919–20). Many of the early senior armor commanders such as Uborevich, Triandafillov, and Tukhachevsky had led cavalry forces during these periods, and were correspondingly responsible for developing much of the Red Army’s mechanized and armored “deep battle” doctrine. During the 1920s “Black” Reichswehr officers, looking to circumvent the restrictive Versailles Treaty, which forbade Germany to possess tanks, cooperated with their Soviet contemporaries by carrying out covert armored company- and battalion-sized maneuvers. In return for technical and tactical knowledge, German commanders such as Guderian received hands-on experience at the secret training facilities near the tank factory at Kazan known as Panzertruppenschule Kama.

Although Soviet armored battlefield tactics steadily improved after 1942 as commanders gained experience, they continued to opt for the simplest battlefield solutions that promoted fighting spirit, and stressing ultimate victory over efficiency and initiative. By the end of 1943, however, Soviet tank and mechanized formations had matured to a point where new organizational structures were not created. Instead, existing formations were improved by the incorporation of specialized forces, which, based on Stavka’s determination, resulted in armored formations being more flexible and balanced than previous mixed structures, thus fitting better within the Soviet technical and tactical capabilities. An insufficiency of radio sets remained a command and control problem, and limited communication between higher commands and their subordinate units, as well as with close air support.

IS-2s of 79th Guards Heavy Tank Regiment with welded hulls. Note the horn and extended main-gun travel lock on the nearest and farthest vehicles, respectively. (Courtesy Mikhail Zharkoy)

While the Germans used combined-arms battlegroups (Kampfgruppen) to undertake tactical goals, the Soviets applied a similar approach with the peredovoi otriad (forward detachment). These mixed formations generally consisted of a tank brigade that was supported by infantry and self-propelled guns, which operated up to 100km in front of the main Red Army force to exploit weaknesses in the enemy’s lines. Up to two days before being committed to battle, participating Soviet armored forces assembled 10–15km behind the front line. Supporting formations such as infantry, engineers, and artillery would also arrive on the scene where they would be task-organized to a depth of 1.5–2km. On the night preceding action, armor and support units would move up to within 1–3km of the forward edge of battle to take up their final positions along an area roughly 1km wide and 2km deep. Generally, a Soviet artillery barrage heralded an offensive, as it tried to soften enemy defenses before a ground assault, especially along the axis of advance. Preceding a Soviet armored breakthrough, sappers (engineers), worked in groups of twos or threes to clear paths through landmines or other obstructions, while aircraft, infantry, and armor attempted to neutralize enemy antitank positions.

During a breakthrough attempt the lead battalion-sized group kept 40–50m intervals between vehicles in the lead, while 200–300m behind, the motorized infantry battalion provided a mix of specialized units such as mortars, antitank, engineer, and assault infantry. Additional heavy armored brigades or regiments (and assault guns) would provide support, as would T-34s on the flanks. Without dedicated armored personnel carriers, the subordinated motorized submachine-gun battalion would ride into battle using Lend/Lease jeeps or simply on the tanks. Around 12 of these desant personnel (tank-riding infantry who dismounted to fight) could be transported on an IS-2 until about 1km from the forward edge of battle, when they would dismount and attempt to provide infantry support for the armor. This made it difficult to exploit a successful breach as to remain integrated the tanks or self-propelled guns needed to advance at the pace of their accompanying infantry.

When assaulting enemy positions IS-2 regiments employed tactics that relied on varying numbers of medium T-34/85s and motorized (mounted) infantry making the initial attack (1) and thereby softening enemy defenses and uncovering points of weakness or heavy resistance. IS-2 heavy tanks and ISU-152 self-propelled guns followed in a second echelon, between 300m and 500m behind. This second-echelon force would concentrate on heavily defended enemy positions at ranges of up to about 1,500m, where their large-caliber rounds proved very effective against area targets. With T-34/85s and artillery covering the flanks (2), the heavy Soviet armor would then move forward to lead the immediate breakthrough phase (3). After disrupting enemy command and control and containing any counterattacks the armor would spearhead any pursuit or exploitation.

Once a breakthrough was achieved, self-propelled artillery was brought forward to help neutralize the area and keep enemy reinforcements from intervening. Firing while on the move resulted in such inaccuracy for any main gun of the period, even those with stabilizing mechanisms, as to make hitting anything other than an area target all but impossible. IS-2 crews (like other Red Army tankmen) relied on the proven fire-and-movement techniques that enabled one vehicle to advance while covered by a stationary partner, and then switch roles after a certain distance.

In defense, IS-2 regiments and their self-propelled artillery support could form a mutually supportive checkerboard formation along the expected enemy path, as well as a mobile reserve. In an urban environment, traditionally the most dangerous for armored vehicles, commanders attempted to get IS-2 formations beyond these potentially built-up areas as soon as possible in an effort to retain momentum, and keep the enemy off balance and unable to develop effective defenses. “Fortress” cities such as Posen and Schneidemühl were simply bypassed, and reduced by predominantly infantry forces.

While IS-2s at least possessed a radio receiver, only company-level commanders and above had transmitters as well. This was seen as an efficient means of inter-vehicle communication as it cut down on cross-chatter and promoted the top-down command style favored by Soviet leadership. During combat, commands were generally made in the open in view of the narrow time frame in which they would be carried out. Specific unit and commander names were coded to preserve security. In addition to radios signal flares were used, as were telephones for more stationary facilities, and although the latter were susceptible to being cut by artillery, they provided the most secure method of communication. Commanders were expected to be at the fore of their tactical commands to provide timely control.

11th Guards Heavy Tank Brigade had been formed from the nearly destroyed 133rd Tank Brigade on December 8, 1942, as per NKO order No. 381. Two months later the brigade became operational and was assigned to Second Guards Tank Army, which was forming in the Stavka’s Strategic Reserve. In August 1944 it was transferred to 1st Belorussian Front as an independent formation along the Warsaw sector, and by year’s end it traded in its KV-1s for IS-2s by incorporating 90th, 91st, and 92nd Heavy Tank Regiments, which had recently formed in the Moscow Military District. Throughout its existence 11th Guards Heavy Tank Brigade fought at several key engagements including Kursk, Korsun, Warsaw–Posen, and Pomerania. During its final operation in Berlin the brigade ended the war near the Reichstag, having been given the honorable designation Korsunskaya, and awarded the Order of the Red Banner for heroism in combat on July 8, 1944.

Actual armor strengths are underlined as xx; TO&E/KStN values for armor and manpower are not.

Commander: Colonel Boris Romanovich Eremeev

Total strength: 65/25; 1,666 men

Brigade HQ: 2/not known

HQ Company (Reconnaissance, Egineer, Chemical Defence, Signal Platoons, Supply Sections)

90th (21/14), 91st (21/6), 92nd (21/5) Guards Heavy Tank Regiments (each 375 men)

Regimental HQ (inc. Staff (1/not known), Signal, Maintenance, Reconnaissance Sections)

4 Heavy Tank Companies (each with two platoons of two IS-2s each plus one IS-2 command tank)

Submachine-Gun, Combat Engineer, Pontoon Companies

Regimental Aid Post

11th Motorized Submachine-gun Battalion (403 men)

Battalion HQ (inc. Antitank Rifle Platoon)

Submachine-Gun Company

Submachine-Gun (“desant”), Mortar (mot.), Antitank, Maintenance Companies