To bolster German defenses along the Oder River and east of Stargard, specifically against Bogdanov’s Second Guards Tank Army as it rampaged across southern Pomerania, 503rd Heavy SS Panzer Battalion was activated at its bases around Berlin on January 25, 1945. With so many trained crews having been sent to the 501st and 502nd Heavy SS Panzer Battalions over the last few weeks, the formation was hard-pressed to provide occupants for its Tiger IIs when word suddenly came that it was to depart for the front line between Friedberg and Schneidemühl. As additional crews were procured the battalion’s new commander, SS-Sturmbannführer Friedrich “Fritz” Herzig, implemented final preparations to enter the fray the following day.

On January 26, after months of intensive training, and having received their final shipment of 13 Tiger IIs from the Heereszeugamt (Army Ordnance Department) at Kassel, 503rd Heavy SS Panzer Battalion entrained for the short ride to the Eastern Front with 39 vehicles. Although doctrine dictated the desirability of allocating such units as a whole to maximize their battlefield potency, the number of threatened sectors along the porous Pomeranian front line pressured German commanders into parceling elements off as circumstances dictated. As the battalion passed through Berlin its 2nd Company’s 1st Platoon was diverted to the Küstrin bridgehead defense as the remainder of Herzig’s command continued on.

Over the next few days the Germans continued to rush forces to Pomerania to establish some sense of order. The unexpectedly rapid Soviet advance across Poland, often with accompanying turncoat Germans fighting under the Nationalkomitee Freies Deutschland banner, had overwhelmed the defenders. To supplement the depleted front-line defenders, a variety of local groups were thrown together and sent into combat, such as Major Günter Kaldrack’s 400 NCO cadets from Arnswalde’s Panzergrenadier School, which fought near Driesen. Not surprisingly these formations suffered heavy casualties, but their efforts helped slow the overextended Soviet spearheads, and bought badly needed time, however minimal.

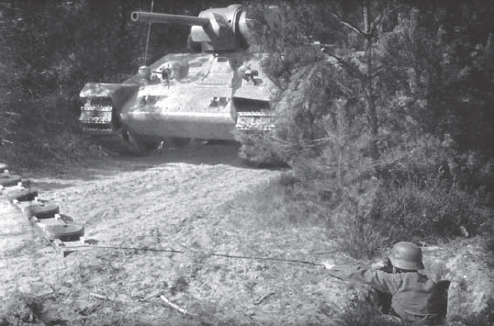

This IS-2 is a victim of a German handheld antitank weapon such as a Panzerfaust. Judging by the cupola smoke the IS-2 succumbed to an internal explosion and fire. (DML)

As 503rd Heavy SS Panzer Battalion entered their assigned sector east of Stargard on the 28th the amorphous front line added to the confusion as the formation’s platoons spread out to strengthen the area’s defenses. After being allocated to Generalmajor Oskar Munzel’s command, Herzig accompanied his Headquarters Company and a dozen Tiger IIs as they were detrained at the Pomeranian district capital at Arnswalde. The remainder of 503rd Heavy SS Panzer Battalion pushed ahead along the northern edge of the Warthe River. Six vehicles from 3rd Panzer Company were shuttled further south toward Friedberg, while three more continued on to Schneidemühl. The remaining Tiger IIs comprised SS-Obersturmführer Max Lippert’s 1st Panzer Company east of Reetz.

With Red Army forces having crossed the Warthe River at Landsberg and Driesen, 3rd Panzer Company battlegroup continued southward to help contain the latter’s bridgehead. With Soviet armored patrols expected in the area, the Tiger IIs were ordered by the local commander, Generalmajor Kurt Hauschulz, to detrain prematurely west of Friedberg and continue toward their destination under their own power. As head of Sixteenth Army’s NCO School at Stargard, he had recently rushed some 800 of his cadets to counter Soviet penetrations between Arnswalde and Schneidemühl. The latter, part of the pre-1939 border fortifications that stretched from north of the town to along the Warthe River, had recently been refurbished by groups including the civil/military construction outfit Organization Todt. Unfortunately for the Germans, the “Pomeranian Wall” had little more than scattered, low-quality Volkssturm militia units with which to defend it, the majority of fortress units having been sent to defend the Westwall (Siegfried Line) against British and American encroachment. Not surprisingly Soviet advances from the south and east quickly made these defenses untenable. The six-vehicle battlegroup would soon fight off Soviet armored probes and antitank positions around Heidekavel, and disrupt what supplies were moving through the area en route to Second Guards Tank Army at the Oder. Additional enemy units, however, soon forced the over-extended Germans to pull back.

“Fritz” Herzig was born on July 18, 1915 in the industrial town of Wiener Neustadt, Austria, near the Hungarian border. On February 20, 1933, shortly after Hitler became Chancellor of Germany, Herzig’s nearly three-month probation for acceptance into the SS ended and he was made an SS-Mann. After promotion to SS-Rottenführer he joined the Party’s newly created paramilitary / combat element, SS-Verfügungstruppe (SS-VT), as part of 5th Company, II Battalion, Deutschland Regiment under SS-Brigadeführer Felix Steiner, on October 23, 1934. A year-long stint at the new SS-Junkerschule (Officer School) in Braunschweig was followed by additional service with Deutschland until mid-1939.

When war broke out with Poland, SS-Obersturmführer Herzig was the ordnance officer for SS Artillery Regiment SS-VT. On October 1, 1940 he was made commander of 3rd Company, 5th SS Motorcycle Reconnaissance Battalion, as part of Nordische Division (Nr. 5) (known as SS Infantry Division (mot.) Wiking after December 21, 1940, when Steiner merged SS-VT Regiment Germania with the Flemish and Dutch volunteers of Westland and the Norwegians, Swedes, and Danes of Nordland). Following staff work with Das Reich’s 2nd Regiment throughout 1942, Herzig, now an SS-Hauptsturmführer, was given command of the division’s 8th (Heavy) Company of Tiger Is. From May 1943 to August 1944 Herzig’s military career continued to focus on armored commands, and related training and instruction duties.

With experienced commanders needed at the front, Herzig was sent to the staff of SS Panzer Brigade Gross where the formation attempted to keep Soviet forces out of Riga and the Kurland Peninsula. Five months later SS-Sturmbannführer Herzig accepted his final command with 503rd Heavy SS Panzer Battalion, which he led from Arnswalde to the fall of Berlin. After days of desperate fighting in the German capital, Herzig won the Knight’s Cross for destroying eight Soviet tanks. By May 2, 1945, with all of his Tiger IIs destroyed or immobilized, he led what was left of his command from the Reich Air Ministry, and crossed the Elbe River to US lines.

Considered an effective commander by his men, Herzig was often distant and impersonal. His devotion to the cause, and bravery on the battlefield, were not doubted, as evidenced by his numerous political, combat, and sports awards. Herzig survived the war only to be killed in an automobile crash less than nine years later.

SS-Sturmbannführer “Fritz” Herzig, commander of 503rd Heavy SS Panzer Battalion. Displayed medals include the Iron Cross (both classes), Wound, and Panzer Assault Badges. (Courtesy Military Antiques of Stockholm AB)

With the remainder of 503rd Heavy SS Panzer Battalion deployed east of Arnswalde, Himmler ordered a portion to organize blocking positions northeast of Reetz against expected Soviet probes. A half-dozen Tiger IIs from Lippert’s 1st Panzer Company set off against sporadic resistance toward the Driesen bridgehead with one of the antiaircraft platoon’s three 4 × 20mm Flakpanzer IV Wirbelwind self-propelled guns. Along with 365 grounded paratroopers from Fallschirmjäger Regiment zbV (special employment) Schlacht the battlegroup merged with elements of a reconnaissance and an antiaircraft battalion at Neuwedell before heading south to win back the recently Soviet-occupied town of Regenthin.

Further east, 2nd Company’s 3rd Platoon deployed three of its four Tiger IIs and the battalion’s antiaircraft platoon at Schneidemühl. With one Tiger II soon succumbing to mechanical problems, the remaining vehicles moved to the eastern edge of town at Bromberger. Soviet artillery steadily shelled the surrounding area from the nearby Schneidemühl Forest as the two Tiger IIs established “hull down” positions behind a protective railway embankment. Leaving the immobilized tank to fight in the forthcoming siege of Schneidemühl, what was left of 2nd Company’s 3rd Platoon was ordered to return to the west to help defend Küstrin. With a small contingent of protective infantry hitching a ride the group avoided Soviet patrols as they made their way past Friedberg and Landsberg to reach their 180km-distant destination on January 30.

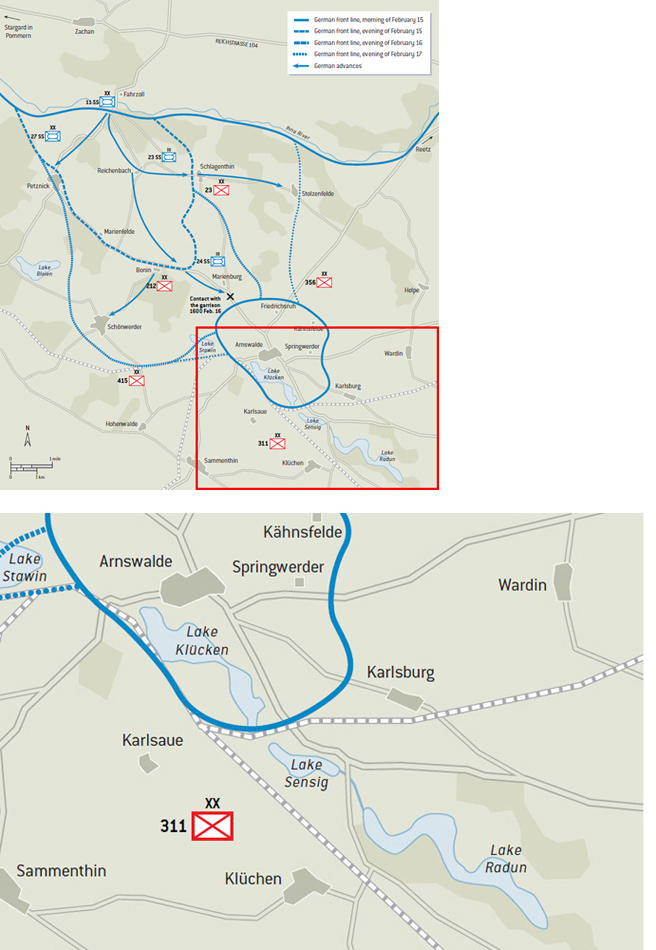

On January 29 Generalmajor Hans Voigt was reallocated from his duties as Commandant of the “Pomeranian Wall” fortresses to that of “Festung Arnswalde” to organize a motley collection of nearby units. Along with Kaldrack’s remaining cadets, Battalion Enge and Replacement Staff for Artillery Regiment zV (“for retribution”), recently freed from their V-2 rocket-launching duties, provided 400 and 800 fighters, respectively, for Arnswalde’s defense. Possessing little more than small arms and a few machine guns these groups were bolstered by two Volkssturm battalions, a Landesschützen (Territorial Defense) battalion, and a detachment from 83rd Light Antiaircraft Battalion that provided two antiaircraft batteries, a 20mm battery, and a 37mm self-propelled Flakpanzer IV Ostwind. With only a handful of 81mm mortars and no artillery, Voigt’s command relied on hand-held antitank weapons and machine guns to provide support, as the former V-2 staff members established security positions at Hohenwalde, Klücken, Kürtow, and Zühlsdorf.

Even the 70-tonne Tiger II could be overturned by artillery or aerial bombing. The lower glacis features Zimmerit; note the emergency escape panel under the radio operator’s compartment and the smaller drain cocks used for purging used oil and other liquids. (DML)

To the east the 1st Panzer Company battlegroup recaptured Neuwedell, but the effort resulted in high losses among the Fallschirmjäger. With a mix of NCO cadets, Volkssturm, emergency, and other units under 402nd Division Staff zbV providing support Lippert set out the following day with his available paratroopers and four Tiger IIs some 10km toward Regenthin. Numerous Soviet antitank guns and infantry, however, forced the Germans to withdraw to avoid being cut off.

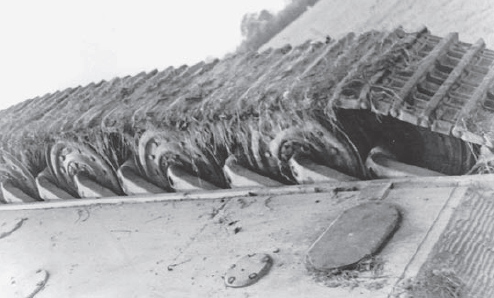

Since pushing west from their bridgehead along the Vistula River on January 16, Colonel Boris Eremeev’s 11th Guards Heavy Tank Brigade made excellent progress as it punched through German defenses ahead of the now ubiquitous T-34/85 medium tanks and mechanized forces. Increasingly urbanized combat and lengthening supply lines took a mechanical toll on the IS-2s, which were routinely doubling their design-estimated battlefield lives. Second Guards Tank Army, for example, lost 52 percent of their tanks and self-propelled guns to enemy armor and artillery, and 43 percent to German handheld antitank weapons such as the Panzerfaust and Panzerschreck in the first 24 days of the Vistula–Oder Offensive. As a defense against the latter, Soviet tankers began to apply makeshift screens made from found materials such as sheet metal, tank tracks, and wire mesh. As shaped-charge weapons needed to impact armor at a set distance to impart maximum destruction, these “bed springs” acted to prematurely dissipate the narrow 500°C jet before it contacted the vehicle’s main armor. Without them the crew risked being engulfed in a molten inferno that externally left a scorched hole dubbed a “witch’s kiss.”

St Mary’s Church was built in Arnswalde’s central marketplace by the Knights of St John in the 14th century. As with most of the town’s structures, the gothic structure was heavily damaged during the 1945 siege. (Courtesy Jarosław Piotrowski)

As the Replacement Staff for Artillery Regiment zV constricted to new positions at Hohenwalde, Karlsaue, Karlsburg, Wardin, and Helpe, the Soviet 88th Guards Heavy Tank Regiment (five IS-2s), 85th Individual Tank Regiment (eight T-34/85s), 43 open-topped SU-76 self-propelled guns, and motorized artillery began moving into the area. Just behind, IX Guards Rifle Corps and XVIII Rifle Corps pushed north, but XII Guards Tank Corps was running out of fuel and only allocated enough for combat and staff vehicles, and a few motor transports.

Tiger IIs knocked out several enemy tanks around Schönwerder, while more such attacks occurred south of Arnswalde. Intent on their own survival many Party officials and the police abandoned Arnswalde for Reetz. Voigt, understandably incensed by the abandonment of the civilians, did what he could to get them out of the enveloping perimeter before it was too late. By the end of the day Tiger IIs repulsed enemy probes near Neuwedell, where 503rd Heavy SS Panzer Battalion’s Workshop Company was located to be close to the fighting.

After several days of frosty weather, February 3 brought warmer temperatures and a thaw that softened ground and made movement increasingly difficult, especially for motorized formations. Southwest of Arnswalde at Sammenthin Tiger IIs rescued some surrounded infantry at Kopplinsthal, and four vehicles from 1st Panzer Company continued on to bolster Arnswalde’s defenses at Hohenwalde. Three Tiger IIs were damaged by heavy enemy armor and antitank fire. The remaining four vehicles fought near a wooded area at Sammenthin, where at 0700hrs the following morning Tiger 111 was destroyed and SS-Untersturmführer Karl Brommann’s vehicle (221) was immobilized by antitank fire and towed by three Tiger IIs to the Evangelical St Mary’s Church in the center of Arnswalde. Armored train No. 77 from Group Munzel provided intermittent local support, but when the Soviets overran the tracks east of Reetz later on February 4 it was forced from the area.

With Soviet forces having reached the Ihna River southwest of Zachen, Steiner ordered Group Munzel to strengthen Arnswalde’s defenses. On February 6 the Nordland Division sent in 15 Sturmgeschütze (assault guns) from 11th SS Assault Gun Battalion and SS-Obersturmbannführer Paul-Albert “Peter” Kausch’s 11th SS Panzer Battalion Hermann von Salza, which held off advancing enemy forces around Reetz. Soviet pressure on either flank, however, proved irresistible as masses of refugees tried to extricate themselves. When the Arnswalde–Reetz road was severed later in the day upwards of 5,000 refugees were trapped within the Arnswalde perimeter. Heavy Soviet artillery made the situation seem all the more hopeless, and Voigt considered capitulation, but did not act on it. In preparation for a rescue of the Arnswalde garrison SS-Untersturmführer Fritz Kauerauf (commander of 2nd Platoon, 1st Panzer Company) was ordered to take three repaired Tiger IIs from the battalion workshop now at Stargard.

503rd Heavy SS Panzer Battalion (seven Tiger IIs; Company HQ)

Artillery Regiment zbV Hohmann

83rd Light Antiaircraft Battalion (20mm single and quad guns)

Urlauber Battalion (comprised of soldiers returning from leave)

Escort Battalion zbV Reichsführer-SS (Gross) (HQ; Signals Platoon; Engineer Platoon; 1st, 2nd and 3rd Schützen Companies; Heavy Machine Gun Company; Heavy Company)

Urlauber Company (from Arnswalde)

Army Standortverwaltung (local administration)

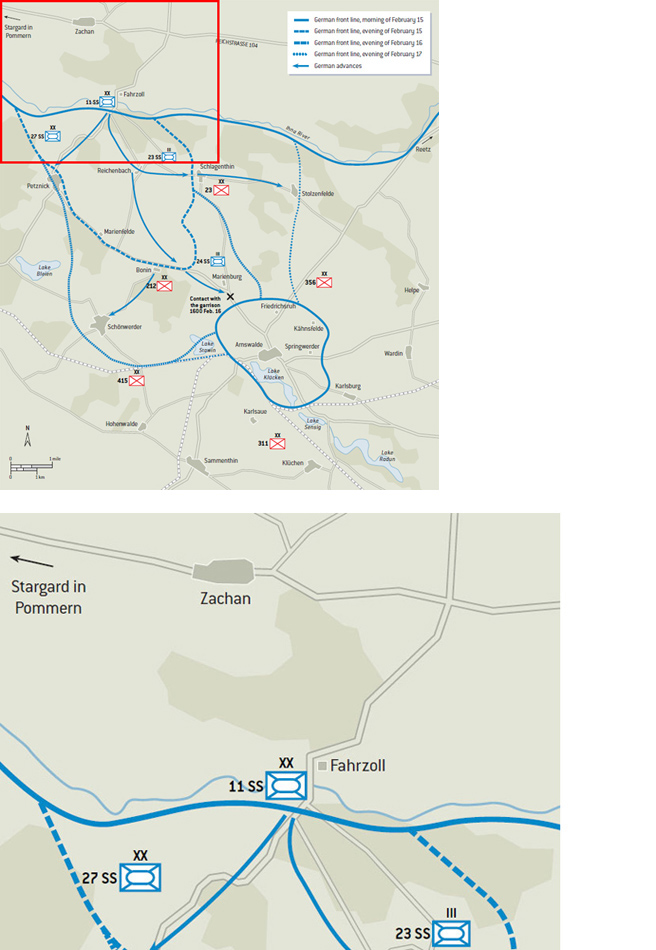

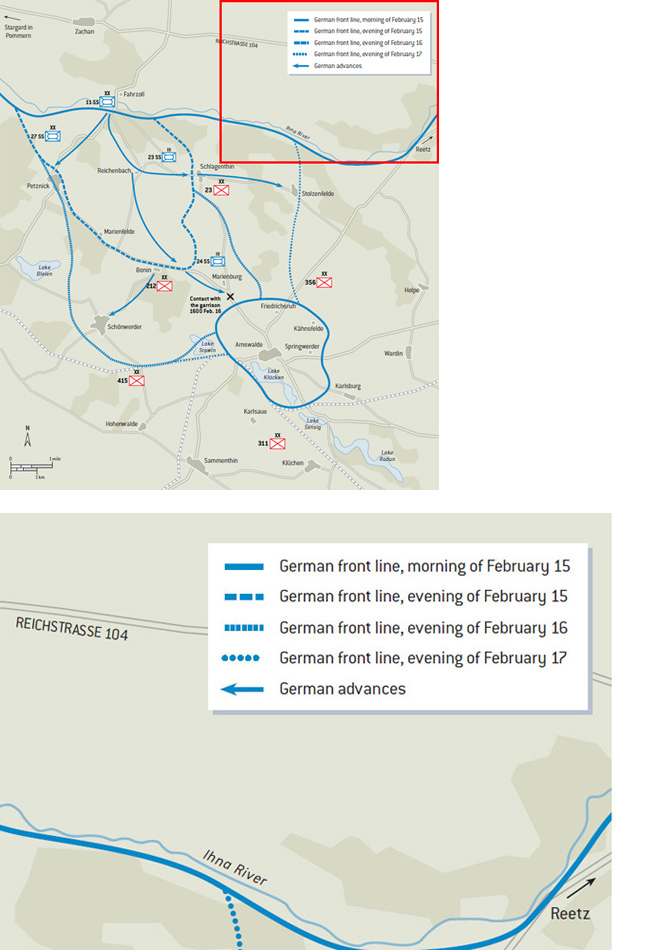

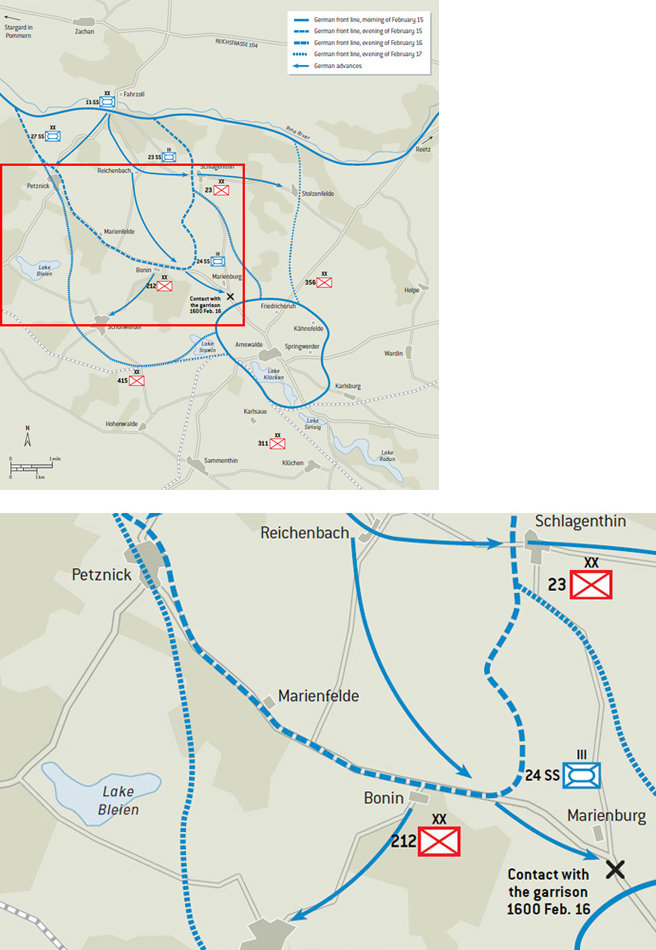

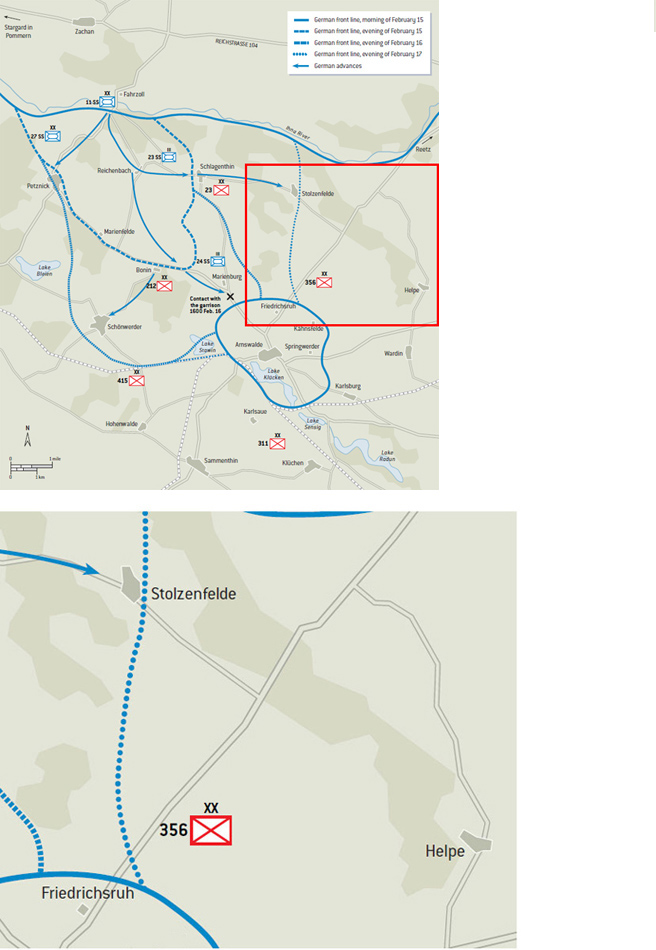

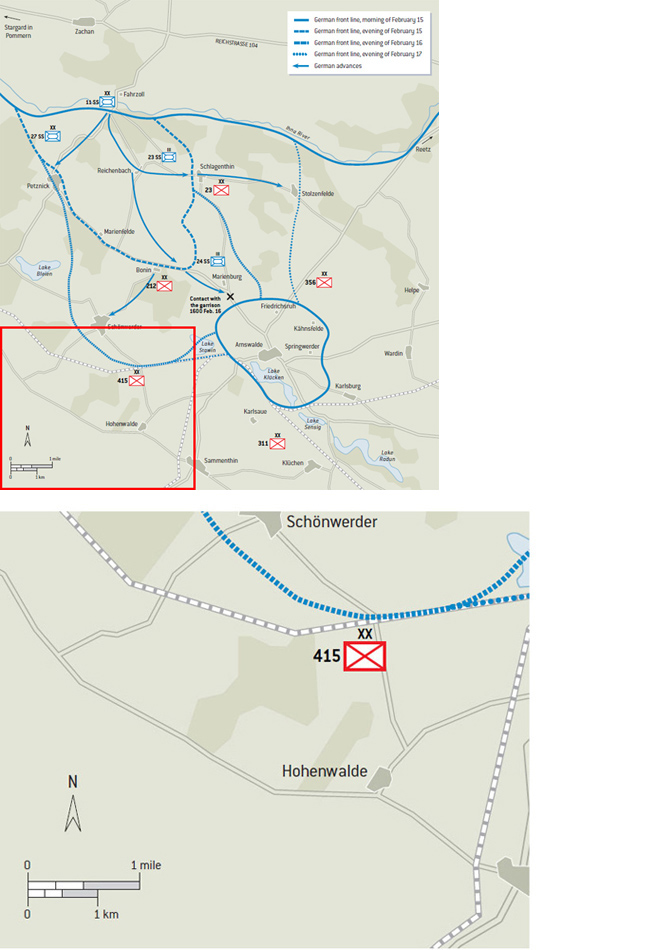

A tactical view of the relief of the Arnswalde garrison, February 15–17, 1945.

The next day Soviet forces pushed back the roughly 1,000-member Dutch brigade, soon re-christened as the loftily titled 23rd SS Volunteer Panzergrenadier Division Nederland, overran Reetz and Hassendorf, and cut Reichsstrasse 104 to Stettin. Considerable Soviet forces, including armor and artillery, snaked their way north along the ridgeline just east of the Ihna River north of Reetz.

At dawn on February 8 Kausch ordered Kauerauf to send one of his Tiger IIs from 1st Platoon, 3rd Panzer Company, and three Sturmgeschütze under the very experienced SS-Obersturmführer Hermann Wild to report on Soviet activity north of Reetz. After moving from Kausch’s headquarters south of Jakobshagen the group crested the high ground just west of Ziegenhagen and saw a seemingly endless enemy column of armor, artillery, and infantry passing through Klein Silber, which if left unchecked threatened to move on to the Baltic coast and cut German forces still moving by land into Pomerania from the east. Wild went for reinforcements, and soon returned with two Tiger IIs, ten additional Sturmgeschütze from Battalion Herman von Salza, and a Fallschirmjäger company as a force with which to eliminate the enemy thrust.

This German soldier sets a German hollow-charge Hafthohlladung 3 antitank magnetic mine in a T-34’s visibility “dead zone” during training. Designed to be placed at an optimal 90 degrees, this mine’s shaped-charge design defeated armor in the same way as the rounds fired from handheld weapons such as the US bazooka and the German Panzerfaust and Panzerschreck. (NARA)

After quickly organizing from the march, the German battlegroup halted to fire on several Soviet antitank guns west of Ziegenhagen around noon. As per the semi-informal Tigerfibel (Tiger Manual), crews were to maintain controlled fire and limit unnecessary ammunition expenditure by being like boxer (and Fallschirmjäger member) “Max Schmeling’s right” and not to use shells until the moment of truth. As Fallschirmjäger moved up on either side of the road past Ziegenhagen and across a bridge into Klein Silber, a pair of Sturmgeschütze led a Tiger II through the latter town amid heavy small arms fire. The assault guns were soon stopped by a Soviet antitank gun near a church some 200m away, but a ridge in no-man’s land obscured each side and forced their fire high.

Kauerauf was apprised of the impasse and moved his taller Tiger II into a hull-down position to knock out the surprised enemy gun crew with a Sprgr 43 HE round. As the German armor began to move on, Kauerauf was soon halted by a hastily laid enemy minefield in the street. The Fallschirmjäger fought their way forward, but with no engineers available one of the paratroopers rushed forward to destroy the mines with grenades and demolition charges. No sooner was the street cleared than a Soviet IS-2 came into view at 50m, which Kauerauf disabled with a Pzgr 39/43 antitank projectile, finishing it off with two more such hits. Two more IS-2s ground to a halt nearby after seeing Kauerauf’s results and simply abandoned their vehicles and disappeared. With the Red Army’s northward advance through Klein Silber now severed the trio of Tiger IIs formed a defensive hedgehog formation along the village’s southern end to take on fuel and ammunition. Over the next day two were destroyed by Soviet infantry and a third by its crew after it became immobilized.

German soldiers in training position a strip of five Tellermine 35 antitank mines against a T-34 Model 1941 (note the “blackout” headlight covers, early tow shackles, and “plate” tracks). Each mine’s 5.5kg charge of TNT would certainly blow off the vehicle’s track, and possibly damage its suspension and injure the crew. (NARA)

As the front line began to stabilize along the Ihna River’s southern edge, Soviet forces focused on eliminating the Arnswalde garrison. At 1000hrs on February 9, eight Tiger IIs led ten armored personnel carriers from I Battalion, 100th Panzergrenadier Regiment, Führer Escort Division, from the bridgehead at Fahrzoll, but the effort to reach the town’s defenders stalled. With fuel and aircraft running low, Luftflotte 6 had several of its venerable Ju-52 transports airdrop supplies to the beleaguered “fortress” during the nights of February 8/9 to 11/12, 13/14, and 14/15. Whether because of oversight or sabotage by foreign factory workers much of the ammunition replenishment for the Tiger IIs was 88mm Flak 36 rounds, which being designed for antiaircraft guns were unusable.

After the Red Army captured perhaps the most formidable section of the “Pomeranian Wall” at Deutsche Krone on the 11th, and Tiger IIs with Battalion Gross devastated a T-34 unit at Kähnsfelde, fighting around Arnswalde waned as both sides regrouped. To test the garrison’s resolve and avoid a costly fight, the Soviets sent three German captives to Arnswalde’s eastern perimeter at Springwerder during the evening of the 12th. Under a flag of truce the trio carried a message from their captors stating that to prevent unnecessary casualties the garrison needed to surrender by 0800hrs the following day. As an incentive the German defenders were told they would then be given food and medical attention, and be allowed to retain their personal effects, and civilians would simply be allowed to go their own way. But knowing the harsh fate that Germans in areas overrun by the Red Army had already experienced, there was little reason for them to expect different treatment.

At the designated time, instead of a white flag, the German defenders defiantly displayed both the German imperial and Party flags from St Mary’s Church. Incensed, the Soviets unleashed an artillery, mortar, and Katyusha rocket barrage lasting over seven hours that did considerable damage to the town. To the east, Schneidemühl’s garrison faced imminent destruction. Organizing into three groups each broke out for friendly lines on the 13th, but a quick Soviet response meant only a few reached their goal at Deutsche Krone. The roughly 15,000 civilians were left to the mercy of the Soviet and Polish forces that would take the city the next day. Having gathered the 16 operational Tiger IIs that weren’t encircled, 11th SS Panzer Army commanders would do everything possible to prevent such a situation at Arnswalde. With most of III (Germanic) SS Panzer Corps having been successfully transported by sea from the Courland Peninsula, Steiner was able to position sizeable forces east of Stargard. To lead 11th SS Panzer Army’s scheduled counterattack, personnel of the Nordland Division conducted training and familiarized themselves with the area in the days leading up to the offensive before being put on alert on February 14.

With relatively warm temperatures continuing, intermittent rain and sleet greeted Eleventh SS Panzer Army as they prepared to go over to the offensive between Lake Madü and Hassendorf. Although Steiner favored first building his command’s offensive capability, Guderian’s timetable won out, and the attack was scheduled to start on the 16th. With the Nordland Division ready a day early its commander, SS-Brigadeführer Joachim Ziegler, met with local commanders before dawn on the 15th to discuss their coming objectives. As they had been allocated 31 Sturmgeschütz III Ausf Gs (1st, 2nd, 3rd Companies), and 30 Panther Ausf Ds (4th Company) there seemed a good chance of at least limited success.

In the gray pre-dawn the Nordland Division’s depleted 24th SS Panzergrenadier Regiment Danmark moved its II Battalion up to its jump-off positions just south of the Ihna River. While they passed into 27th SS Volunteer Grenadier Division Langemarck’s security zone/bridgehead south of Fahrzoll Nordland’s 11th SS Engineer Battalion strengthened the light wooden bridge over the river to provide a crossing for the supporting German vehicles as the surrounding terrain was too soft for such movement. With I Battalion, 100th Panzergrenadier Regiment (Führer Escort Division) not yet prepared to support Nordland, Regiment Danmark’s Danish volunteers began their attack at 0600hrs with the intent of relieving Arnswalde’s garrison as a prelude to the wider effort to sever Second Guards Tank Army’s spearheads.

By noon Regiment Danmark’s II Battalion had recaptured Reichenbach, while their supporting tanks and Führer Escort Division’s half-track personnel carriers crossed the Ihna River. Surprised by finding themselves on the defensive, Soviet forward elements from 212th and 23rd Rifle Divisions fell back in confusion. Exploiting the situation, elements of Battalion Hermann von Salza plus 11th SS Panzerjäger Battalion’s 3rd Company and a platoon from that battalion’s 1st Company advanced on either side of Reichenbach at 1400hrs and continued toward Marienburg. To the left the Norwegians of 23rd SS Panzergrenadier Regiment Norge’s II Battalion (Nordland Division) attempted to secure the operation’s northern flank, but were unable to wrest Schlagenthin away from the Soviets. By day’s end companies from the Langemarck Division had established positions before Petznick and Regiment Danmark held positions near Bonin where their patrols made contact with Voigt’s encircled command.

A Tiger II defends the Arnswalde perimeter near Kähnsfelde. On February 10, 1945, Tiger IIs, with support from Escort Battalion zbV Reichsführer-SS, stopped a Soviet assault on the Arnswalde perimeter at Kähnsfelde. To make the best use of the Tiger II’s long range, these vehicles were positioned along the small hills that bordered the area’s low-lying, swampy terrain and its small bisecting stream, the Stübenitz. With ammunition running low the German commander had to be very selective in choosing targets. Because of their firepower and protection, IS-2s would be a primary focus, but the more numerous medium T-34/85s could not be ignored. As high-explosive rounds would not be effective in targeting enemy armor, the Sprgr Patr 43 (HE) would probably be used against infantry when a sector was threatened with being overrun.

On Friday 16th, Operation Sonnenwende officially commenced. On the German right XXXIX Panzer Corps’s Holstein Panzer Division and the nearly full-strength 10th SS Panzer Division Frundsberg burst into XII Guards Tank Corps’ security zone, and pushed 34th Guards Mechanized and 48th Guards Tank Brigades back to south of Lake Madü. The Frundsberg Division’s subsequent efforts to link up with 4th SS Polizei Panzergrenadier Division, which with 28th SS Volunteer Grenadier Division Wallonien was to form a pocket around Soviet forces between Arnswalde and the lake, came to naught. A quick and stubborn reaction by 66th Guards Tank Brigade with some 15 T-34/85s made further German progress near the area’s saltworks difficult. The southern Belgians from the Wallonien Division, essentially a 4,000-man battlegroup, made every effort to support the Nordland Division’s right flank, but could make little headway past Lake Plöne. Along Eleventh SS Panzer Army’s left X SS Corps began its own offensive around Reetz. Using the Führer Escort and Führer Grenadier Divisions the formation made initially good progress even though confronted by considerable Soviet antitank defenses.

Comprising the primary German effort in the center, III (Germanic) SS Panzer Corps crossed the Ihna River to reinforce the Nordland Division’s success the previous day. The Soviet VII Guards Cavalry Corps fell back in some disarray, but XVIII Rifle Corps continued to maintain its grip around Arnswalde. Until greater numbers of heavy Soviet artillery could be redirected northward, the front line was not likely to solidify any time soon. Sixty-First Army commander Colonel-General Belov moved to reduce the Arnswalde garrison before the Germans could break the siege by sending two heavy tank regiments from 11th Guards Heavy Tank Brigade to the area as a breakthrough element for 356th and 212th Rifle Divisions. Having only 260 and 300 soldiers available for action, respectively, the force was in poor shape to undertake such a mission. 85th Tank and 1899th Self-Propelled Artillery Regiments were subsequently moved up to provide armored support for a re-implemented attack that included 311th and 415th Rifle Divisions once they arrived on the scene.

Tiger IIs from 503rd Heavy SS Panzer Battalion were able to effectively engage enemy armor at long range, but the recent thaw had created very muddy terrain that hindered movement. The Germans knew that if the ground will support a man standing on one leg and carrying another man on his shoulders, it will support a tank. Although considerably reduced in strength by recent fighting along the Baltic coast, the Nordland Division continued to fight through sporadic Soviet resistance. Retaining the element of surprise, German forces exploited the situation to resolve their mission as quickly as possible in spite of environmental conditions unsuited for armored operations.

In response to the broader Sonnenwende operation Soviet commanders activated several local IS-2 formations for a counterattack. Lieutenant-Colonel Joseph Rafailovich’s 70th Guards Heavy Tank Regiment (Forty-Seventh Army) was positioned north of Woldenberg, while Lieutenant-Colonel Semen Kalabukhov’s 79th (XII Guards Tank Corps) assembled near Dölitz. Lieutenant-Colonel Peter Grigorevich’s 88th Guards Heavy Tank Regiment was also available near Berlinchen in Sixty-First Army’s sector.

Regiment Danmark’s III Battalion was ordered to take Bonin with support from Führer Escort Division’s mounted Panzergrenadiers and three Sturmgeschütze from the Nordland Division. On establishing a defensive position south of the village and the nearby Volkswagen factory the half-tracks and assault guns turned for Schönwerder to assist Regiment Danmark’s II Battalion. I Battalion, 66th SS Grenadier Regiment (Langemarck Division) launched a concurrent attack with Regiment Danmark’s III Battalion’s effort to take Marienfelde and establish a combat outpost at Petznick. Following these assaults, Regiment Danmark’s II Battalion was to capture Schönwerder, while Regiment Norge captured Schlagenthin and pushed outposts to Stolzenfelde to anchor the corridor’s left flank.

At 1600hrs parts of Regiment Danmark broke from their positions at Bonin and captured Schönwerder in a quick assault. As additional companies reinforced the success, the remainder of the battalion weathered XVIII Rifle Corps’ artillery fire to reach Arnswalde’s northwestern perimeter and break the 11-day siege with a defensible corridor. Seven Tiger IIs that had been attached to the Nordland Division soon entered the town along with other reinforcements that proceeded to strengthen the garrison’s defenses. As the Germans expanded the corridor, strong enemy resistance along the Stargard–Arnswalde railroad stopped further progress in that area. To the north contact was made with parts of Regiment Danmark’s III Battalion along the tracks with friendly units at Marienburg.

On the 17th, Second Guards Tank Army arrived in force in the Arnswalde sector and stopped what little impetus the Frundsberg and Polizei Divisions retained. While the latter tried to work into the flank and rear of XII Guards Rifle Corps and 75th Rifle Division, 6th Guards Heavy Tank Regiment moved up to counter the effort. The Wallonien Division continued to hold on to their positions in the Linden Hills, with one company fighting nearly to the last man against repeated enemy assaults.

A front view of a well-used IS-2 that appears to have suffered damage along the side of the hull. As an early “broken-nose” model it has a narrow mantlet. Note the missing tow shackle and the other IS-2 to the right. (DML)

Around Arnswalde, 14 IS-2s from Hero of the Soviet Union Major Prokofi Kalashnikov’s 90th Guards Heavy Tank Regiment moved up to join the already-in-action 91st and 92nd with six and five IS-2s respectively, but success remained elusive. 356th Rifle Division managed to get infantry elements into the suburbs near the city’s gas works, but German infantry firing from the upper floors of buildings, and roaming Tiger IIs, made infiltration impossible.

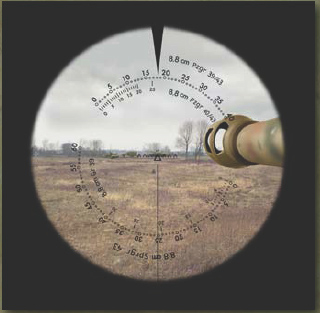

A Tiger II gunner uses his TZF 9d sight to target an IS-2 as it is resupplied by a US Lend/Lease supply truck at 1,800m

Here we see the view through a Tiger II’s TZF 9d gunsight targeting an IS-2 as it and another are resupplied by a Lend/Lease supply truck. Believing themselves to be safely out of enemy range, the two halted IS-2s take on supplies and fuel before moving up for an attack. Soviet support personnel go about their business next to an American IHC M-5-6×4-318 supply truck. When the Soviets went over to the strategic offensive in 1943, foreign-provided Lend/Lease equipment and vehicles such as this one greatly assisted with logistics.

Fine-tuning his aim from 2.5× to 5× magnification, the gunner prepares to fire a PzGr Patr 39/43 APCBC/HE-T round into the unsuspecting enemy vehicle’s thinner side armor

The Tiger II’s firing sequence proceeds similarly to that on the IS-2. With a projectile ready in the breech, and if the target is beyond some 500m, the gunner estimates the target’s actual size and divides it by the number of mills it encompasses in the ’scope. The loader adjusts the tick marks on the Turmzielfernrohr 9d monocular gunsight in accordance with both the selected ammunition and the range, the latter being agreed upon by the driver, gunner, and commander. Once it is rotated so that the large black triangle at the ’scope’s top points to the estimated range, the upper tip of the large central triangle atop the vertical line is located between the targeted IS-2’s turret and hull.

With a stable corridor out of Arnswalde now available Voigt quickly orchestrated the evacuation of the civilians and wounded. Although briefly severed, Soviet efforts to permanently eliminate the 2km-wide corridor were unsuccessful. Of the original seven garrison Tiger IIs, only four remained operational. Battered and in need of maintenance, the vehicles were withdrawn to Zachan.

Just after midnight on the 18th the commander of the German offensive was seriously injured in a car accident. While returning to the front following a briefing at the Reich Chancellery, Wenck had taken the wheel from his driver, who had also been on duty for over two days straight, only to fall asleep himself. Suffering from a fractured skull and broken ribs, Wenck was replaced by Generalleutnant Hans Krebs, but the offensive’s momentum could not be maintained.

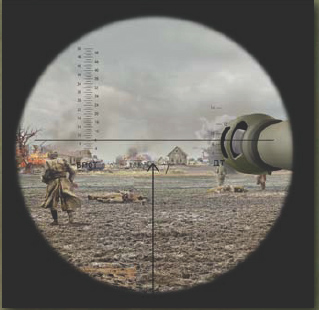

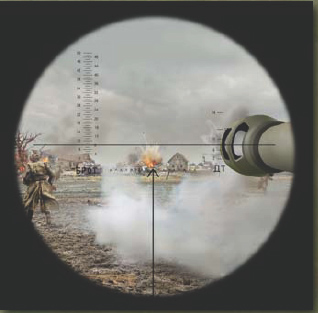

The view through an IS-2’s TSh-17 gunsight targeting a defending German Tiger II at 800m

In an effort to penetrate the defensive line around Arnswalde, Soviet infantry move forward in a dispersed formation to minimize casualties. Receiving small-arms and mortar fire, many of the attackers have fallen but the remainder continue on through smoke and churned earth. The attackers wear the M1940 steel helmet or shapka-ushanka synthetic pile winter cap, as well as khaki padded telogreika jackets and greatcoats.

The forward German positions extend around the outskirts of the town, with trenches and foxholes placed so as to make the best use of terrain. This line is manned by infantry and reinforced by the occasional machine-gun crew. To their rear a Tiger II, partly camouflaged by rubble and earth, provides support.

Using one of their eight BR-471 armor-piercing rounds, the Soviet crew scores a hit against the target’s frontal armor

Once the IS-2 commander has called out a target type and location, the loader assembles the proper round and charge and positions it within the breech. The IS-2’s gunner correspondingly uses the TSh-17 gunsight to estimate range by using the angled mill marks. Once the range is determined the horizontal line is positioned at the correct “БΡΟΓ” scale for armor-piercing rounds, or the “ДΤ” for the coaxial DT machine gun and high-explosive rounds, with the arrow’s tip placed over the target. Crews seldom fired on enemy armor beyond 1,200m as it accomplished little save exposing the IS-2’s firing position.

In Arnswalde, Voigt met with the new commander of III (Germanic) SS Panzer Corps, Generalleutnant Martin Unrein, to discuss the deteriorating situation and withdrawal from their extended positions. Unrein, having taken over on February 10 after recovering from an illness, found himself in the unusual position of an Army commander of Waffen-SS forces. Seeing that further efforts would not alter the failure of Sonnenwende he agreed to let Voigt extricate his command from Arnswalde. Soviet pressure to the east and west of the town threatened to collapse Voigt’s battle zone and close combat was already occurring in parts of the town, but III (Germanic) SS Panzer Corps’ artillery helped keep Soviet forces at bay throughout the day.

After sunset civilians and wounded began to evacuate Arnswalde and move back along Regiment Danmark’s route to Zachan some 20km to the northwest, where trucks waited to take as many as they could west. With Sonnenwende nearing its unsuccessful end 503rd Heavy SS Panzer Battalion received orders that it was to be transferred to the fight raging around Danzig and Gotenhafen. Although heavy fighting flared up around Arnswalde’s military base and near the railroad station, self-propelled antitank guns from 1st Company, 11th SS Panzerjäger Battalion, moved in to support the town’s defenders, while the exodus from the combat zone continued.

For the Nordland Division, February 18 was relatively quiet, but reconnaissance indicated a strong enemy buildup west of the Stargard–Arnswalde railroad. Another company from the Langemarck Division was inserted between Marienfelde and Regiment Danmark’s II Battalion to reinforce the area. German offensive activity had to stop due to increasing Soviet pressure, and Himmler called an end to Sonnenwende the following morning.

On February 19, Zhukov initiated his planned offensive aimed at capturing Stettin using the Sixty-First and Second Guards Tank Armies as well as the VII Guards Cavalry Corps, which remained embroiled in heavy street fighting at Arnswalde. With Soviet pressure threatening once again to encircle the town and destroy its defenders, Voigt and Ziegler developed a plan to evacuate their fighting elements from the town. A Soviet armored assault comprised of T-34/85s, IS-2s, and KV-1s was repulsed 3km northeast of Arnswalde at Friedrichsruh. Throughout the day Regiment Norge and Regiment Danmark were subjected to enemy artillery that included multi-barreled “Stalin’s Organs” as they rebuffed Soviet probes toward Schönwerder.

Belov ordered 23rd Rifle Division to go over to the offensive after relieving VII Guards Cavalry Corps. XVIII Rifle Corps was to cease its assault on Arnswalde’s perimeter, and attain a defensive stance, although Soviet assault teams within the town were allowed to continue their activity. What IS-2s were in support were forced to operate with their hatches closed to minimize damage from hand grenades and handheld antitank weapons, many of which were being used from higher building elevations. To compensate for the loss of visibility and control in the urban environment “herringbone” tactics were used, in which a four-vehicle platoon would be divided into two pairs of tanks. In what was basically a variation of fire-and-movement, the first pair would advance along a street with each vehicle focusing to the right and left, respectively. From a stationary position to the rear, the remaining two IS-2s provided supporting fire.

To improve tactical flexibility and success, each tank company was allocated a submachine-gun platoon. These infantrymen rode the tanks into action, and dismounted to ferret out German Panzerfaust hunter/killer teams, and other resistance. To further motivate the destruction of enemy armor, NKO issued order No. 0387 on June 24, 1943, to pay out 500 rubles to the tank commanders and drivers, and 200 rubles to the loaders and gunners, of the vehicles responsible for a kill. Artillery and antitank crews received similar bonuses, which eventually increased to 1,000 rubles for individuals single-handedly accomplishing the task.

By February 20 Group Munzel and Voigt’s command managed to get all their civilian charges and wounded out of the combat zone without incident, due in no small part to the Nordland Division’s constant struggle to keep the corridor open, a feat seldom accomplished to any great degree at other “fortress” cities. The next day German artillery kept Soviet forces at bay, while the garrison made final preparations to disengage from their perimeter defenses and withdraw back to III (Germanic) SS Panzer Corps’ former positions along the Ihna River. The other forces involved in Sonnenwende were similarly pulled back, or remained in positions perceived as defensible, so as to make it appear that at least one military objective was accomplished. German units that had participated in Sonnenwende began to be pulled from the sector to regroup or be redirected to other threatened areas.

Placing a makeshift Stielhandgranate 24/gas-filled jerry can improvised explosive on the engine deck of enemy armor was one of several tank destruction methods listed in the German manual called Die Panzerknacker (“the armor cracker”). The victim here is a T-34 Model 1941 with early rubber-rimmed road wheels. (NARA)

Regiment Norge and Regiment Danmark received orders to the effect that with the Nordland Division’s flanks so extended, the corridor to Arnswalde could not be maintained, and that the front would soon be pulled back. Petznick was never taken by the Langemarck Division. At 1700hrs the first of three groups of defenders began their march northwest out of Arnswalde’s defenses. The remainder followed at 1800 and 1900hrs, with SS-Sturmbannführer Heinz-Dieter Gross leading the rearguard at 2000hrs. After 15 days of combat, Voigt’s command quietly and efficiently left their positions without arousing enemy suspicions.

A section of the Stargard–Arnswalde railroad about 3km west of the latter. After taking Schönwerder on the 16th, elements from 11th SS-Panzergrenadier Division Nordland pushed past 212th and 415th Rifle Divisions and expanded the recently created corridor to Arnswalde. (Courtesy Mariusz Gajowniczek)

Just before midnight Regiment Danmark’s II and III Battalions began to withdraw back to Bonin, with the latter acting as a regimental rear guard and observation force for another day. Four hours later Soviet artillery fell on Schönwerder, which unknown to the Soviets had already been abandoned. At dawn forward Soviet units discovered that the Germans had left the immediate combat zone and began a cautious approach north to regain contact. At noon on the 22nd VII Cavalry Corps elements were repulsed at Bonin.

At 2200hrs that night Regiment Danmark’s II Battalion continued to hold its position at Petznick to act as flank protection for the Fahrzoll bridgehead as Danmark’s III Battalion crossed the Ihna. About 45 minutes later Regiment Norge’s III Battalion pulled out of Schlagenthin and crossed as well, followed by Danmark’s II Battalion. When the final German unit, Norge’s 10th Company, moved to the river’s north bank the recently reinforced bridge to Zachan was blown up.

Starting on February 23, Zhukov’s commitment of the Seventieth Army into an attack spurred a general German retreat from along the Ihna River. As the Germans had not received orders to pre-empt such a situation and establish new defenses to the rear many vehicles and equipment had to be abandoned. Two days later Red Army forces captured an abandoned Arnswalde. With 1st Belorussian Front now assisting Rokossovsky in clearing Pomerania, it would be another six weeks before the Soviets would initiate their long-awaited offensive against Berlin.