Although service in an armored vehicle would seemingly impart a reduced physical risk compared to infantry and artillery units that were not protected against bullets, shrapnel, and weather, tank crewmen faced their own hazards. While World War II infantry suffered higher physical casualties, tankers were afflicted with a greater incidence of mental disorders related to working and fighting in a hot claustrophobic environment where direct contact with the outside world was limited. Constant vibration caused knee and back problems, edema (fluid pooling), muscle atrophy, and radiculitis (spinal nerve inflammation). Explosions from antitank mines or forceful, non-penetrating projectile impacts could cause blunt trauma and shower the interior with spall. Carbon monoxide buildup was especially problematic, especially when the vehicle was “buttoned up” with its hatches closed. Noise was an ever-present problem during operation, where those exposed to constant noise exceeding 85dB hearing damage. With the firing of main guns and movement often producing 140dB and between 120dB and 200dB respectively, effective communication and target detection was often hampered due to crew disorientation.

While medium armored fighting vehicles such as the German Panther or Soviet T-34 possessed a balanced triad of firepower, mobility, and protection that permitted them to undertake a variety of combat roles, the Tiger II’s greater weight relegated it to more limited defensive operations. Its size made movement through urban environments or along narrow roads difficult, while its drivetrain was under-strength, the double radius L801 steering gear was stressed, and the seals and gaskets were prone to leaks. Limited crew training could amplify these problems as inexperienced drivers could inadvertently run the engine at high RPMs or move over terrain that overly tasked the suspension. Extended travel times under the Tiger II’s own power stressed the swingarms that supported the road wheels and made them susceptible to bending. Such axial displacement would probably strain the tracks and bend the link bolts to further disrupt proper movement. Over-worked engines needed to be replaced roughly every 1,000km. Although wide tracks aided movement over most terrain, should the vehicle require recovery another Tiger II was typically needed to extract it. Requirements for spare parts were understandably high, and maintenance was an ongoing task, all of which reduced vehicle availability.

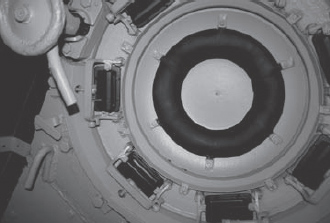

This interior view of a Tiger II’s cupola shows the hatch wheel/lever (at upper left). The seven brackets held replaceable glass vision blocks should they become damaged. (Author’s collection)

The Tiger II’s long main armament, the epitome of the family of 88mm antiaircraft/antitank guns that had terrorized enemy armor since the Spanish Civil War (1936–39), fired high-velocity rounds along a relatively flat trajectory. In combination with an excellent gunsight, the weapon system was accurate at long range, which enabled rapid targeting and a high first look/first hit/first kill probability. However, the lengthy barrel’s overhang stressed the turret ring, and made traverse difficult when not on level ground. Optimally initiating combat at distances beyond which an enemy’s main armament could effectively respond, the Tiger II’s lethality was further enhanced by its considerable armor protection, especially across the frontal arc that provided for a high degree of combat survivability. Although the vehicle’s glacis does not appear to have ever been penetrated during battle, its flanks and rear were vulnerable to enemy antitank weapons at normal ranges.

In the hands of an experienced crew, and under environmental and terrain conditions that promoted long-range combat, the weapon system achieved a high kill ratio against its Allied and Red Army counterparts. 503rd Heavy SS Panzer Battalion, for example, was estimated to have scored an estimated 500 “kills” during the unit’s operational life from January to April 1945. While such a figure was certainly inflated as accurate record keeping was hindered by the unit’s dispersed application and chaotic late-war fighting where the Soviets eventually occupied a battlefield, it illustrated the success of the weapon system if properly employed and supported. Of 503rd Heavy SS Panzer Battalion’s original complement of 39 Tiger IIs only ten were destroyed through combat, with the remainder being abandoned or destroyed by their crews due to mechanical breakdowns or lack of fuel. As 503rd Heavy SS Panzer Battalion never received replacement tanks like its brethren in 501st and 502nd Heavy SS Panzer Battalions (which were given 2.38 and 1.7 times their respective 45-vehicle TO&E allotments), its Tiger II combat losses averaged less than 50 percent.

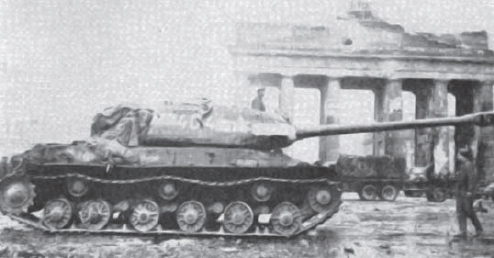

An IS-2 with a welded, streamlined glacis and a 12.7mm DShK 1938 antiaircraft machine gun. The photograph appears to have been retouched at the end of the gun barrel, either to obscure the background or to emphasize the muzzle brake. (DML)

Because of the chaotic combat environment throughout Pomerania, and the need to quickly allocate resources to several threatened sectors at once, the Tiger IIs were frequently employed singly, or in small groups, often at the will of a local senior commander. In much the same way as with the French in 1940, 503rd Heavy SS Panzer Battalion’s armor acted more in an infantry-support capacity than as a unified armored fist. The Tiger IIs would perhaps have been better used organizationally to fill a Panzer regiment’s heavy company by strengthening existing, depleted parent formations; but instead they remained in semi-independent heavy Panzer battalions until the end of the war. Forced to rely on small-unit tactics, Tiger II crews played to their strengths by adopting ambush tactics to minimize vehicular movement and pre-combat detection, especially from enemy ground-attack aircraft.

As tankers regularly spent long hours in their mounts the Tiger II’s relatively spacious interior helped reduce fatigue, and made operating and fighting within the vehicle somewhat less taxing. A good heating and ventilation system improved operating conditions, which then reduced crew mistakes that were all too common during a chaotic firefight. Although the Tiger II had well-positioned ammunition racks that facilitated loading, projectiles that were stored in the turret bustle were susceptible to potentially catastrophic damage caused by spalling or projectile impacts. Even after Henschel incorporated spall liners to reduce such debris, concerned crews would often leave the turret rear empty, which correspondingly made room to use the rear hatch as an emergency exit.

The cost to produce the Tiger II in manpower and time (double that of a 45-tonne Panther), and its high fuel consumption, brought into question why such a design progressed beyond the drawing board considering Germany’s dwindling resources and military fortunes. It was partly a response to the perpetual escalation of the requirement to achieve or maintain battlefield supremacy, and much of the blame rested with Hitler and his desire for large armored vehicles that in his view presumably reflected Germany’s might and reinforced propaganda. By not focusing resources on creating greater numbers of the latest proven designs such as the Panther G, German authorities showed a lack of unified direction and squandered an ability to fight a war of attrition until it was too late to significantly affect the outcome. Limited numbers of qualitatively superior Tiger IIs could simply not stem the flood of enemy armor.

When the Red Army transitioned to the strategic offensive in early 1943 their skill in operational deception increasingly enabled them to mass against specific battlefield sectors, often without the Germans realizing the degree to which they were outnumbered until it was too late. Purpose-built to help create a breach in the enemy’s front-line defenses the IS-2’s relatively light weight, thick armor, and powerful main gun made the design ideal for such hazardous tip-of-the-spear operations. Once a gap was created, follow-up armored and mechanized formations were freed to initiate the exploitation and pursuit phase of the Red Army’s “deep battle” doctrine. Here, more nimble vehicles such as the T-34 could concentrate on moving into an enemy’s flank and rear areas to attack their logistics and command and control capabilities. Unlike the mechanically unreliable KV-1, the IS-2 had a surprisingly high life expectancy of some 1,100km. Able to cover considerable distances on its own, as evidenced during the Vistula–Oder Offensive, it remained at the fore of Soviet offensive operations until the end of the war.

With some 20 HE rounds out of an ammunition complement of 28, the IS-2 was well suited to attacking targets such as fortifications, buildings, personnel, and transport vehicles. In this capacity its heavy, two-piece ammunition and slow loading and reaction times were not much of an issue. Against armor such delays could prove catastrophic. Should the 122mm D-25T gun score a hit, however, its relatively low-velocity projectiles imparted considerable force that could severely damage what they could not penetrate. Having a large quantity of low-grade propellant, its rounds created a considerable amount of smoke that could reveal its firing position. Its periscope did not provide all-around viewing or quick targeting reconciliation, and traversing the large, overhanging barrel was often impeded when the vehicle was not on level terrain. Thoughts of increasing the mantlet thickness were stillborn as any additional weight to the turret’s front would only exacerbate the problem. In a potentially fast-paced tank battle, where being first to get a round on the target generally decided the contest, the IS-2 was often at a disadvantage.

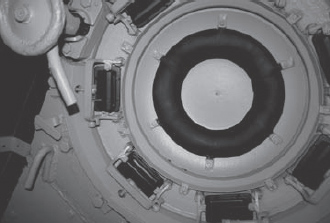

A view of a Tiger II cupola showing the rough aiming device, which could be aligned with a small vertical rod (out of sight on the right) to allow the commander to provide a rough target direction to the gunner. A “Pilz” and armored plate for the ventilator fan are also shown. (Author’s collection)

As the IS-2’s glacis presented a fairly small surface area its turret was the most likely target for enemy antitank weapons. As a defense against German handheld antitank weapons such as the Panzerfaust and Panzerschreck, IS-2 crews made increasing use of ad hoc metal turret screens or skirts to disrupt the effect of the warhead’s shaped-charge. Although prone to deformation in cramped urban environments, any such protection was better than nothing.

An IS-2 from 7th Guards Heavy Tank Brigade with quickly applied identification-friend-or-foe white turret stripe (the roof would have had a white cross) before the Brandenburg Gate, Berlin. As the unit had recently fought near the Arctic Circle the turret carries a white polar bear over a red star. The truck towing an antitank gun appears to be a Soviet ZIL-157. (DML)

Although Soviet tank crews received less training than their German counterparts, especially for drivers, the IS-2’s rugged construction was more forgiving than its Tiger II rival. Crew safety and comfort were secondary considerations to Soviet tank designers throughout the war, as evidenced by the rough application of welding and seaming, and construction techniques. Like the mass-produced T-34, the IS-2 was a relatively simple, rugged design that facilitated construction and in turn provided numbers to overwhelm the enemy and help bridge the gap between Soviet and German capabilities after a long period of German technology superiority.

During the fighting around Arnswalde IS-2s possessed better mobility, but the relatively open terrain and limited foliage plus the greater range of the Tiger II largely prohibited the Soviet tanks from getting close to the town – and the Germans focused on enemy tanks over other targets.

Throughout World War II the difficulty in developing, fielding, and supporting a variety of armored vehicle sizes and types was readily apparent. Manufacturing capability, raw material availability, design scope creep, and a pressing need for battlefield supremacy were only a few of the culprits. The resulting mix of light, medium, and heavy tanks and self-propelled guns, often with overlapping and redundant capabilities, and incompatible parts, was cost-prohibitive to maintain. Nations increasingly focused on a single main battle tank design (as well as light air-mobile varieties) that could be modified and upgraded as needed. As the 30-tonne American M4 Sherman and Soviet T-34 designs had proved themselves in combat, had been mass-produced, and were capable of accepting a variety of modifications, such logic continued into the postwar period. With the proliferation of portable, handheld antitank weapons many postulated armor’s demise on the modern battlefield. Although the basic composition of tanks has changed little over 60 years, advancements in armor, armament, and performance, as well as communications and targeting, have allowed such vehicles to remain viable not just in high – but also in increasingly low-intensity combat environments.