CHAPTER 10

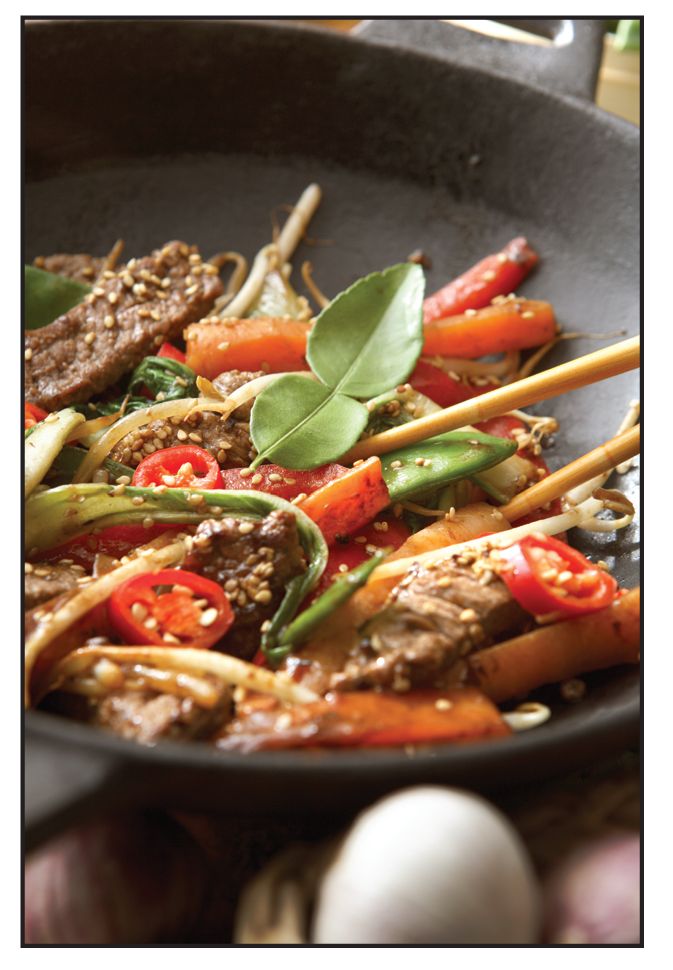

THE WOK

China is a country which traditionally has had a lot of people to feed and not much meat to offer them. Sort of like some deer camps I’ve been in. A full meat pole, game bag, or stringer is nice but certainly doesn’t occur in any camp with enough regularity to plan meals around. This is where Chinese cuisine, the product of a fuel- and meat-poor culture, really shines.

The Advantage of Stir-Fry Cooking

Creating stir-fry dishes in camp satisfies several demands of the practical camp cook. First you can get by—and do so very well indeed because the entire cuisine is designed this way—with relatively little meat as compared to traditional Western cooking.

Secondly, stir-fry cooking is simple. It requires minimal utensils and can be prepared as well over an open fire ten watery miles from the nearest highway as it can in a fully-equipped home kitchen. Stir-fry cooking is peasant cooking, and guess what Chinese peasants used to cook over? You guessed it, an open fire.

Stir-frying generally requires less fuel than many camp cooking techniques. This can be an important factor under some conditions. You need an intense heat to get the wok hot and keep it that way throughout the cooking process, but there is no need for the lengthy, wood-consuming wait as your fire burns down to a bed of coals. Nor will you have to endure the long, gas-gulping simmering asked of a camp stove. Some stoves on the market have only one heat setting, conservatively described as inferno, or perhaps Mt. St. Helens. This fearsome blast of unregulated heat that blackens bannocks and burns the bottoms out of aluminum pots is just the ticket for stir-frying where hotter is better.

The natural flavors and colors of foods are enhanced and intensified when they are stir-fried. The quick application of heat neither dulls the brilliant colors of vegetables nor destroys the vitamin content. Meats are not overcooked but cooked until just done, with similar nutritional benefit.

A final stir-frying benefit is built into the cuisine itself. A stir-fried meal enables the camp cook to stretch a duck or a lonely brace of grouse or a dozen crayfish to feed three, four, or five campers.

Finally, stir-frying is fast. Hot, great-tasting, nutritious camp meals can be whipped out in a wok in literally half the time you would spend on a similar repast using some Western cooking method. You can be sitting down to a gourmet outdoor meal within an hour of first walking or paddling into camp. You won’t even have to wait for the fire to burn down to coals as this technique demands a hot, reflector oven-type fire.

Stir-frying is traditionally done in a wok, a cooking pan shaped like half a sphere, from the size of a basketball on up to the giant institutional models. While stir-frying can be done in almost any pan, as long as it is steel or cast iron for the heat-retention properties of these metals, the wok is easier to work. Its high sides prevent the contents from spilling as you swirl them about, and the rounded, upward-sloping outside surface provides a more even heating surface. There are aluminum and thin lightweight steel woks on the market. These utensils suffer from the same problems as similarly constructed frying pans. They tend to form “hot spots” directly at the point where the heat is applied, conducting little of the energy to the rest of the cooking surface.

Seasoning a New Wok

The steel wok is seasoned much like the Dutch oven. Coat the inside with a good, high-temperature oil such as peanut oil. Heat the pan until the oil smokes then allow it to cool. Wipe the inside thoroughly and repeat the process. While the ideal is to be a good cook and never burn any food to the surface of your wok, requiring only a gentle wipe to clean it after use, reality sometimes deigns otherwise.

Wash your wok with a mild soap only. Stay away from any kind of grease-cutter type of chemicals, and oil and heat it again after each use. This is less of a job than it seems from reading about it. Simply give the inside of the wok a quick wipe with the oil and set it over the fire or stove as you conduct some other after-dinner chore. The cooking surface of your wok will turn black with use. Your scrubbing instincts will rebel against this. Resist. This is the original non-stick cooking surface, and it will serve you well if you take care of it.

The wok was designed for use over an open fire.

Stir-frying requires cooking oil. While any old oil, strictly speaking, will work, try to stay away from the generic salad or cooking oils. Peanut oil is the best bet for stir-frying. It has a good flavor, it’s okay for any other oil usage in camp, and it can handle the high temperatures found both in wok cooking and in seasoning the wok, Dutch oven, or iron frying pan without burning.

Stir-frying as a method of cooking is different from anything you have taken on before. The idea is to apply intense heat to the food for a very brief period. It really is about as easy as that, and the technique offers several unique benefits.

The Technique of Stir-Frying

Before we cook from a recipe, let’s run through the technique of stir-frying. You must have all the necessary ingredients laid out, ready to go and handy to reach, before you begin. The in-and-out-of-the pan style of cooking here leaves no room for fumbling around through a pack or field kitchen searching for ingredients, and setting the meal aside halfway through will definitely not add to a meal that is designed to be cooked quickly and served hot.

Cut your vegetables long and thin, when possible, avoiding the small, diced style of Western cooking. If using cuts of meat (as opposed to quartering a bird or smaller animal), cut the slices thin, long, and against the grain. The faster each piece of meat or vegetable cooks, the better it will taste in your stir-fried meal.

First, prepare your fire or stove and fuel it so it’s hot and will stay that way through the ten or fifteen minutes you’ll spend cooking. If you’ll be serving rice with the meal (a natural, nutritious, and tasty accompaniment), cook it ahead of time and set the pot by the fire to stay warm—stir—frying will require all your attention.

Once your wok is hot almost to the point of making the oil smoke, add some or all of the food ingredients. Stir-frying demands that the high temperature stay pretty constant throughout the process, hot enough to make the meat or vegetables crackle. If you’re making any more than a very small recipe, then begin with the meats and cook the ingredients one or two at a time.

There’s the frying, now for the stirring. The food ingredients must be kept in constant motion, stirred while they cook. The moment you let them lay against the sides or bottom of the wok with all that intense heat for more than a moment you are going to overcook something. You want meats cooked just through, at most, and vegetables left with most of their bright colors. They should still be almost as crunchy as when they entered the wok. There are various impressive oriental-looking cooking utensils on the market but for our purposes a spatula or wooden spoon works very well and can serve for other camp kitchen chores as well.

The recipes we’ll use here are bound with a liquid mixture of a stock, cornstarch, and soy sauce for seasoning. After the meats and vegetables have been cooked and set aside, heat the wok again and add the meats and vegetables and the stock all together. As this mixture heats up it will thicken. Remove the wok from the fire and eat.

STIR-FRY MALLARD

2 ducks (grouse, pheasant, etc.)

2 tablespoons peanut oil

2 carrots, sliced thin

1 large onion, sliced thin

2 cloves garlic, diced

2 stalks celery, sliced thin

1 cup chicken stock (made with bouillon cube)

4 teaspoons cornstarch

1/4 cup soy sauce

Cooked rice to go with the meal

Fry the garlic in the oil. When it’s just cooked through, remove and discard it. Cook the duck or bird pieces until just cooked through, then remove. Add the vegetables to the wok, one at a time, removing as each is just warmed through. Add more peanut oil if needed. Mix the soy sauce, chicken stock, and cornstarch. Add to the wok, stirring first as the cornstarch tends to settle on the bottom, and when boiling, add the cooked ingredients you have previously set aside. When the liquid again comes to a boil and the sauce thickens, remove from the heat immediately.

This process is so simple it doesn’t take much more time to accomplish than it has taken you to read about it. It’s also incredibly adaptable to changes in recipe items. Stir-frying a meal can absorb with ease and style any kind of meat or fish taken during the day, nuts gathered, and mushrooms or wild edible plants picked.

On page 162 is a simple camp stir-fry recipe, a good one to begin with. You can bone the ducks if you want to take the time and trouble, I usually just quarter them. Cook the duck quarters first, as they will take considerably longer due to their large size.

BEEF JERKY ORIENTAL

1 clove garlic

1 cup, or about 6 sticks, beef jerky

1/2 cup mushrooms, sliced

1 carrot, sliced thin

1 small onion, sliced thin

1/2 cups nuts, acorns if available

2 tablespoons peanut oil

1/4 cup water

1/4 cup soy sauce

2 tablespoons cornstarch

Soak the jerky the night before to soften it, and cut it into bite-sized pieces. Heat the wok, add the oil, cook the garlic and discard it one at a time (or double up if the quantities are small), cook the beef, carrot, onion, and mushrooms, and remove all from the wok. Mix the water, cornstarch, and soy sauce, add it to the wok, and when it’s hot put the other ingredients back in the wok, along with the nuts.

STIR-FRIED CRAYFISH TAILS

2 dozen crayfish tails

1/2 cup sliced fresh mushrooms

1/2 small onion, sliced thin

2 stalks celery, sliced thin

2 tablespoons peanut oil

1 teaspoon cornstarch

1/4 cup water from cooking crayfish

1/4 cup soy sauce

1/4 teaspoon cayenne pepper

1 small piece ginger root

Heat the oil in the wok and cook and discard the ginger root. Cook the mushrooms, celery, and onion and remove. Mix the water from boiling the crayfish, soy sauce, and cornstarch and add to the wok. When the mixture is boiling add the cooked vegetables and crayfish tails. Add cayenne pepper, using more than the 1/4 teaspoon if you appreciate hot food.

The wok is a great way to cook strong-tasting fish-eating ducks. Skin and trim the fat from the birds. Marinate them overnight in a mixture of two parts water, two parts red or white wine, and one part soy sauce.

The stir-fry on page 163 uses beef as the meat item. By substituting freeze-dried or dehydrated vegetables from an oriental grocery store for the fresh carrots and onions and dried mushrooms, it fits right into the backpacker or canoe camper’s menu.

Fresh water lobsters are easy and fun to catch, but you can’t always get enough for a crayfish boil. Prepare the crayfish for the recipe on page 164 by soaking them in fresh water to purge them, then boil them in salted water with a shot of lemon juice, if you have it in camp, until the shells turn red. Remove them and let them cool. Break the tails from the crayfish, and crack the shells to extract the meat. Reserve the cooking water.

For a really solid, hot dish, replace the cayenne pepper with some sliced jalapeno peppers, fried and discarded with the ginger root.

Don’t Forget the Rice

I can’t prove this, but I suspect that at least as much rice is cooked outdoors over open fires around the world each day as is cooked indoors in civilized kitchens. Around a third of the world’s population eats rice every day. “Wilderness potatoes,” as rice was named by trappers in the white silence of the north country in the last century, lends itself admirably to the camp kitchen. It is light, nutritious and will not spoil if kept reasonably dry. It is a good energy-provider for active outdoors people. It tastes great plain, and lends itself to an endless variety of rice dishes, from serving as a side dish or base to those mentioned in this chapter, to rice pudding for dessert.

Cooking rice is one of the greatest exercises in simplicity found in either the civilized or wild kitchen. Use two parts water to one part rice. Boil the water, add the rice, simmer for fifteen or twenty minutes. That’s all. Eat it.

Once you use your wok a few times I wager you’ll take it along more often. There are things it does not do well—the curved bottom is not the answer for the fried egg, for example—but the backpacker or canoe tripper willing to experiment a little might find the answer to the ultimate, one pan-only trail kitchen to be one of the world’s oldest cooking utensils.