CRAFTING THE PEACE

Although American diplomats were deeply involved in crafting the treaties that ended their Revolution, the principal decision-makers were Britain’s Lord Shelburne and France’s comte de Vergennes, who were in truth more concerned with the balance of power in Europe than with American independence. —Editors

The treaty signed in Paris on September 3, 1783, by representatives of Great Britain and the new United States formally ended a grueling seven-year war. Negotiations over the contours of American independence among the two British and four American representatives had dragged on since April 1782.

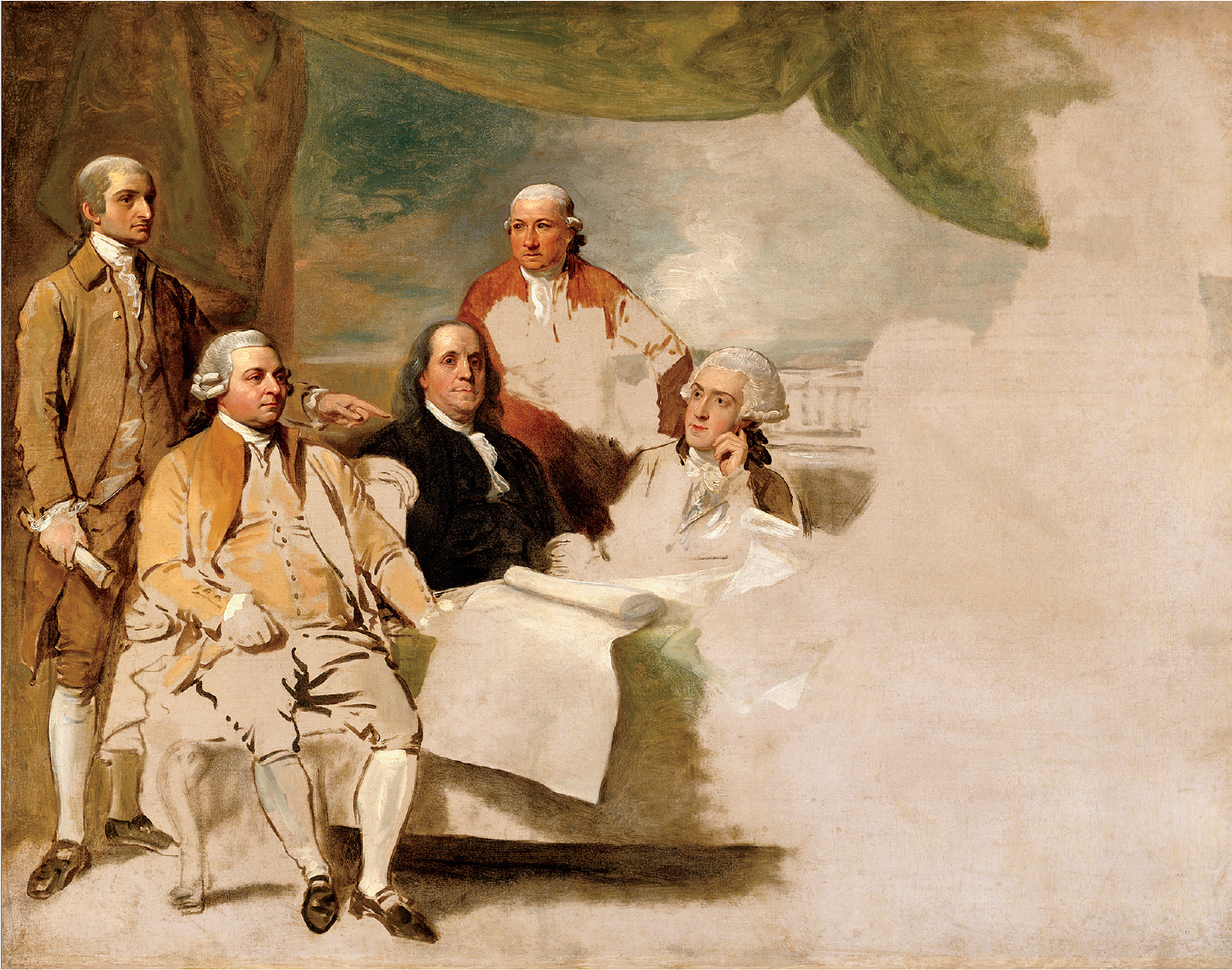

The Pennsylvania-born artist Benjamin West sought to capture their achievement. Soon after preliminary articles of peace were signed in early 1783, he began work on a group portrait of the negotiators (see facing page). Seated at the table are John Adams on the left; Benjamin Franklin in the center, staring straight out at the viewer; and Henry Laurens, whose head rests wearily on his hand, on the right. John Jay stands on the left side of the canvas, above Adams, pointing to Franklin, the most senior member of the delegation, while Franklin’s secretary and illegitimate grandson, William Temple Franklin, stands between him and Laurens. Documents crowd the table. Behind them, a window draped with thick curtains of a muddy chartreuse color opens onto a landscape with a white house in the background and an intense blue sky above it.

But the right side of the canvas is empty. West’s portrait of the peacemakers proved impossible to finish, despite the fact that, living in London, he was well situated to capture the characters of all concerned. Britain’s principal representative, the merchant Richard Oswald of London and Auchincruive in Scotland, and his secretary Caleb Whitefoord, do not appear: both Scotsmen were reluctant to be memorialized as the men who gave away the bulk of Britain’s North American colonies, especially after Parliament’s hostile reception of the preliminary articles struck on November 30, 1782. Always sensitive about his looks (some thought him ugly; he was certainly vain, needing spectacles and an ear horn but loath to use them in public), Oswald actively resisted sitting for West. Admittedly, it might have been inconvenient, as he resided in France and Scotland much of the time, but he also refused to allow the only portrait he had of himself—a primitive 1750 marriage portrait that he disliked intensely—to be used as a model. Just over a year after the signing of the definitive articles of the treaty, he died at his seat in Ayrshire.

Benjamin West, American Commissioners of the Preliminary Peace Negotiations with Great Britain, 1783 (unfinished). Oil on canvas. (Winterthur; Department of State, Diplomatic Reception Rooms, Washington, DC)

Gilbert Stuart, Caleb Whitefoord, Secretary, 1782. Oil on canvas. Whitefoord was one of Lord Shelburne’s representatives in the Paris peace negotiations. (Montclair Art Museum, 1945.110)

West held on to the unfinished oil sketch until his own death in 1820. Thereafter it passed through the hands of several collectors, including J. P. Morgan and H. F. du Pont, who made it a centerpiece of his new Winterthur Museum. Two copies survive—one in the diplomatic reception rooms of the U.S. Department of State in Washington, D.C., and another on a wall of the John Jay Homestead in Katonah, New York. The U.S. Postal Service clumsily reworked West’s image in a stamp issued to commemorate the 1983 bicentennial of the peace.

According to some historians and art historians, the absence of the British negotiators from West’s depiction symbolizes either the division between the mother country and its former colonies or an assertion of American independence and will. These conclusions are implausible. We know the omission was not West’s intention. More likely, the British negotiators’ nonappearance reflects their view that the former colonists were simply not the most important parties to the peacemaking—hard as that is for subsequent generations of Americans to fathom.

More striking in the lush visual depiction of the negotiations is the absence of the true architects of the peace: Charles Gravier, comte de Vergennes, Louis XVI’s chief minister; and William Petty-Fitzmaurice, second Earl of Shelburne, George III’s prime minister. Too easily forgotten, these two political leaders deftly directed—and often micromanaged—the negotiations.

Antoine-François Callet, Charles Gravier, Comte de Vergennes, Ministre d’État des Affaires Etrangères (1719–87), ca. 1774–87. Oil on canvas. (© RMN–Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY)

Jean-Laurent Mosnier, William Petty, 2nd Earl of Shelburne (1737–1805), 1791. Oil on canvas. (ART Collection / Alamy Stock Photo)

Historians often describe the peace the two ministers constructed in 1782 and 1783 as Britain’s caving in to the United States. Britain gave away so much, it is said, because the North American insurgents had won the war and then, with more wily and moralistic representatives, the negotiation; Americans gained so much because weak, gullible, and corrupt British ministers and negotiators had steered the ship of state to financial weakness and defeat. Historians treat Britain’s separate negotiations with France, Spain, and the Dutch Republic, as well as the United States’ dealings with them, as second-order diplomacy. This narrative is driven on the one hand by triumphalist American historians writing a victors’ account of the war and its aftermath, as those in any country are wont to do, and on the other hand by defeatist British historians who did not see much to extol in the huge losses of men and land (except for the expansion of territorial empire in Asia), and who saw in the loss of America a prefiguration of further decline two centuries later.

Through a twisting of historical sense, West’s painting can be made to fit the American narrative of superiority and dominance. But the reality is a much more complicated story, one that has to do with the British and European personalities involved in the peacemaking process; their philosophies, programs, and aspirations; and their need to consider one another’s motives—not just those of the Americans—in crafting the diplomatic outcome. That is to say, the British negotiators had more to consider than just the territory of the United States, its wily and moralistic negotiators, and American concerns. It was the British working in concert with the French who really commanded the peacemaking, and their leaders were, despite having been on opposite sides of the conflict, more united than divided.

Historians have looked at the negotiations variously. British historians such as Vincent Harlow in the 1950s argued that the peace was shaped by overseas and, to a lesser extent, domestic developments. The Crown and ministers preferred trade over territory, as exemplified in the “swing to the East” that supposedly recentered their empire in Asia during and after the loss of America. In contrast, American historians like George Bancroft in the 1870s and Samuel Bemis and Richard Morris in the 1930s and 1960s, respectively, adopted a moralistic and patriotic stance. For them, the peace was an unequivocal moral and strategic win for clever, superior Americans and a total loss for inept, inferior, and corrupt Britons.

However expansive their outlook, historians in both camps largely ignored what was going on in Europe, Africa and India. As the historian Andrew Stockley has suggested in the most thorough recent analysis of the peace, earlier scholars have failed to take account of the simultaneous discussions and negotiations being conducted between and among Britain, France, Spain, the Dutch Republic, Austria, Switzerland, Sweden, and Russia. There is another way to tell the story of the peace, Stockley suggests: analyzing its outcome as the product of more international, multivariant factors. Shelburne in London may be the most important party, inasmuch as he was the mastermind and midwife of four separate treaties.

Who Was Lord Shelburne?

Shelburne’s life, personality, and philosophy decisively shaped the diplomacy of 1782 and 1783, and he contributed to the highly interconnected European, Atlantic, and often global endeavor. While he was commonly referred to as a “friend to America” throughout the revolutionary period, when crafting and selling the terms of peace Shelburne did not consider or deal only with the former colonies and their negotiators. Indeed, his correspondence reveals that France loomed larger and more continuously in his mind, and other European states weighed on it heavily as well. In crafting the treaties, he adroitly balanced the desires and needs of the French, other Europeans, and Americans with those of Britain and its empire. In crafting solutions, he combined an idealistic, cosmopolitan philosophy and outlook with a pragmatic approach to problem solving that, at least in the short run, maintained the balance of power in Europe.

Shelburne was one of the most influential leaders of the late-eighteenth-century anglophone world. His family had lived in Ireland since the twelfth century and had adhered to the Catholic faith until the 1690s. He would inherit vast estates in Ireland, England, and America. He studied for several years at Christ Church, Oxford. He served as a volunteer military officer with the British army in France and Germany in the late 1750s. Although elected to the House of Commons in 1761 at age of twenty-four, he never took his seat: on the death of his father, he was elevated to the House of Lords, and there he sat for the next forty-four years, towering above his peers as one of the Whigs’ great orators and head of one of their many factions. An avid, informed “Improver,” he tinkered not only with soils and crops on his many Irish and English estates but also with economic, social, political, and religious practices throughout all of Britain in attempts to better his estate, his nation, his continent (for he thought of himself as also a citizen of Europe), and his empire. He died in London in his palatial Berkeley Square home in 1805.

Shelburne was a formidable intellectual and cosmopolitan figure who sought to advance literature, science, arts, religion, and society. He read and collected books in seven languages (of which he spoke four), amassing one of the largest and most influential private libraries in Britain. He visited Paris nearly every other year, purely for personal enjoyment. Abroad and at home, he gathered around himself some of the era’s greatest free thinkers, encouraging, imbibing, and promoting their work; to them, he evangelized about his belief in the unity of European and American culture.

The record on Shelburne’s personality is mixed. He was both much despised and much loved. He was called a Jesuit, or at least Jesuitical, a modern-day Malagrida (a Jesuit missionary who exerted great influence at the Portuguese court and whose name came to signify a smooth, informed but specious interlocutor). Because Shelburne was able to talk on any side of any issue, he was seen as insincere. To many, he appeared to possess no principles at all. He experienced frequent and often unpredictable changes of opinion and looked to others to influence him. He was accused of being a knave and a liar, deceitful, deceiving, or misleading. More, he was accused of double dealing, working to people’s disadvantage behind their backs. He also attracted and consciously gathered about himself not aristocratic peers but “the middling sort”—educated and professional men such as Adam Smith, Richard Price, Jeremy Bentham, Francis Baring, John Dunning, and Samuel Garbett.

After Shelburne became the prime minister in 1782, his contemporaries found new traits to decry. He was seen as having a “passionate or unreasonable…temper and disposition,” alternating between violence and equanimity (Rose 1860: 1: 25). He frequently exhibited whimsical behavior. As one observer noted, he possessed “an inequality of temper” that made him difficult to please (Knox 1902: 6: 283).

But was it true? Was this the same man who commandingly moved the items in negotiation like so many pieces in a cool game of chess? Along with his detractors, there were those who praised him—many in private but a few in public. As James Boswell observed toward the close of his Life of Samuel Johnson, “Man is in general made up of contradictory qualities, and these will ever show themselves in strange succession” (Boswell 1826: vol. 4, 389). Shelburne was no different. But most of his peers and political contemporaries were not men of much introspection, and the roughly dozen highly damning traits stuck to his name, regardless of reality or relevance.

Greater insight into Shelburne and his dealings with fellow peers, politicians, and diplomats in 1782 and 1783 comes from realizing that he suffered from an inability to connect with others. Initially, his upbringing and his parents’ treatment of him left him feeling alone and unsure of himself. He suffered emotional trauma after the deaths of his three sisters during his childhood and the later loss of his two young wives, his second-born son, and his only daughter. Moreover, from birth, he coped with chronic eye and ear diseases. Finally, he experienced serious financial problems, always spending more than he earned and having to mortgage and remortgage his properties. He died a bankrupt (Hancock, forthcoming).

Detachment greatly overshadowed anxiety in Shelburne’s psychological makeup. In particular, the effect of having two emotionally distant parents continued to affect his behavior even as an adult. Many of the traits identified by his political foes in 1782 and 1783 can be seen as those of someone who had for decades tried to keep people at a distance.

The dislike and envy felt by contemporaries, and Shelburne’s detachment from them, shaped his peacemaking probably more than anything else. By temperament, he was a lifelong compromiser. Throughout his long career in politics, he was willing to change his mind on particular matters when given more or different information. Unsurprisingly, this trait created difficulties for him by giving others the erroneous impression that he sought only to please others and exercise power. But in almost all cases, the turn had to do less with ingratiating himself with others than with confronting and embracing new information or a situation different from the one he had expected.

On occasion, Shelburne would concede on a matter of principle. From the start of the peace negotiations in 1782, for instance, he had wanted to defer the acknowledgment of American independence until the final terms had been crafted and confirmed—not, as the Americans wished, to recognize it as a condition for treaty making, for he believed such a position would not wrest the Americans from their reliance on the French. Yet by August 1782, he had conceded the issue in order to move the process forward and to draw the Americans to his side, or at least away from the French.

On material matters, Shelburne made repeated concessions to the United States and France: he was pilloried at home for giving away too much. The loser in the war for America, Britain had little bargaining power over the victors: even so, Shelburne did not give everything away, and when he did make a concession, he did it to gain a complementary advantage on some other front. He refused to cede Canada to the United States, for instance, as Franklin had proposed in April and again in July. On this point Shelburne was supported by Vergennes. Both men wanted some check on American imperial ambitions.

Shelburne and Vergennes struck a similar accord over their overlapping and competing interests in the Newfoundland fishery. France wanted a French fishery on the northwestern, western, and southern coasts of Newfoundland, as sanctioned by the Treaty of Utrecht. Britain refused to cede the southern coast but construed the western coast as 130 miles longer than under the French definition and understanding. France also wanted exclusive fishing rights in the areas granted, not the concurrent rights Britain proposed. Shelburne resolved the matter with ambiguous language, thereby conceding nothing. With respect to the reclamation of France’s Indian possessions, France wanted some area granted around its trading posts in India to supply and protect them and also wanted to strengthen the forts. Britain refused these requests, allowing only the construction of a sanitation ditch encircling Chandannagar and an armistice for French allies on the subcontinent, thus retaining the upper hand. Finally, while entertaining Vergennes’s premier commis (first secretary) Joseph Matthias Gérard de Rayneval at his Wiltshire country seat and his London townhouse in mid-September, Shelburne called for economic cooperation in the form of freer trade between the two powers, a position with which Vergennes agreed. By early October, he and Vergennes had agreed that the time was not right for negotiating political and commercial amity and that the status quo should remain. Shelburne preferred that it do so for only a few years, whereas the French wanted to set no deadline for reaching agreement. Shelburne won the point.

Artist unknown, Conrad Alexandre Gérard de Rayneval, ca. 1780. Engraving. (Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints, and Photographs: Print Division, New York Public Library)

Shelburne compromised with Spain as well. While he implied in mid-August 1782 that he would consider handing over Gibraltar to Spain, he later withdrew the offer. It is not clear whether it was ever meant in earnest or just as a ploy to bring the parties to the negotiating table. With the success of the British navy’s final relief of Gibraltar on October 10 and the failure of the subsequent Spanish siege, British desire to keep the peninsula grew stronger, and the cabinet opposed ceding it. Accordingly, Shelburne abandoned the idea in early December.

The Dutch posed a different challenge. With them, Shelburne worked out an agreement on the terms of peace. His long-time personal and political enemy Charles James Fox, as secretary of state for foreign affairs under the prime minister, the second Marquess of Rockingham, had agreed in April to allow the Dutch the freedom of navigation that had been stipulated by the 1780 League of Armed Neutrality. But when Shelburne replaced Rockingham at the latter’s death on July 1, 1782, Shelburne rescinded the offer. The Dutch were also demanding the restoration of colonies and the compensation of losses. In response, Shelburne demanded the retention of Trincomalee, the main port town of Ceylon (modern Sri Lanka), which Britain had captured during the war, as well as of Demerara and Essequibo, two valuable sugar colonies on the north coast of South America. Vergennes, who had more or less pushed the Dutch aside and negotiated on their behalf, balked at this proposal. Throughout December and January, the two ministers wrangled. Shelburne settled for possession of Nagapattinam on India’s Coromandel Coast, as well as the British right to navigate freely (but not to trade) in the Dutch East Indies, while the Dutch held on to Trincomalee and the right to trade in their own zone.

Could these demonstrations of concession and compromise induce Europeans and Americans to promote greater international harmony and balance? Shelburne and Vergennes thought so: indeed, it was their ultimate goal.

In resisting, conceding to, and compromising with France, Shelburne was ever the idealist. He believed strongly in partnership among civilized nations. He resolved the dilemma of negotiating with France by following the fashionable, enlightened precepts of cosmopolitanism, an ideology that competed with the creeds of patriotism and nationalism. A collector and reader of all the works of the new Enlightenment ideology, Shelburne hoped that a more sophisticated understanding of the nature of polity, the extension of the principle underlying constitutionalism, economic and social development, and the equivalence of belief systems would bring Britain, Europe, and America closer together, politically, practically, and morally. While separate, Britain and France were also joined by a common culture, and Shelburne the peacemaker worked to recognize and perpetuate the ties between them. He hoped that by working together, they would establish the rules that the other European states would have to follow.

It is hardly surprising that Shelburne readily found common ground with Vergennes. From his time at Oxford and his first visit to France from 1757 to 1760, through the darkest days of the French Revolution, he never wavered in his admiration of French culture and thought. Nearly a third of his library of nine thousand volumes consisted of works of French history, politics, and literature.

Thus, beginning in 1782, a friendship based first on admiration, then on trust, developed between the two chief ministers. Before Shelburne and Vergennes ever corresponded, they had been in agreement in their desire to avoid the co-mediation of their disputes by Austria and Russia. In the ensuing months, they jointly and individually worked to keep Canada from the United States, keep Gibraltar from Spain, and keep the Dutch from exerting absolute control over trade in the Dutch East Indies. Shelburne’s complementary ideas of amity, union, and balance became the watchwords of his negotiations, much as they had guided his earlier political career. Continually the negotiators emphasized consideration, respect, moderation, and justice. Shelburne and Vergennes strove to preserve a balance of power between small and large states, in particular by keeping Russia and Austria from expanding at the expense of Turkey and the Crimea. Both wanted France and Britain to work harmoniously together to keep the peace in Europe.

In seeking cooperation and rapprochement, Shelburne was not merely indulging his appreciation of the French way of life and his admiration of some of its ministers: he was moved by pragmatic considerations as well. His rather small following and weak support in Parliament counseled for an early resolution to the negotiations, as did the dwindling finances of the treasury he managed.

Even so, Shelburne’s effort to achieve peace and establish real harmony in 1782 and 1783 was also motivated by a philosophical and sentimental belief in “solid friendship”—certainly with the United States, but even more so with France. His service in the Seven Years’ War, first on the battlefield and then as the emissary of the prime minister John Stuart, third Earl of Bute, in some of the peace negotiations, had convinced him of the necessity of rapprochement with France. During his several tours of France in the 1770s, he was struck by the cultural affinities between the two polities, and he argued to no one in particular that the two countries should not be in opposition. Indeed, as recently as June 1780, he had lamented in the House of Lords that Britain had missed an earlier opportunity of reconciliation with France (Hancock, forthcoming).

While it is easy to see with hindsight that Britain could have survived a few more years of struggle, many well-informed individuals at the time thought otherwise. As the British treasury dwindled, a resolution to all the conflicts seemed urgent. Moreover, Shelburne’s ministry had only a five-month window while Parliament was not sitting in which to construct a peace without impedance from lesser politicians and special interests, and without hectoring and badgering from Parliament, to derail their progress.

By 1782, American independence was a foregone conclusion, even if Shelburne wanted to delay acknowledging it. The prospect of a stable Europe was not. From the voluminous documentation produced by the peacemakers, supporters, and opponents, it is evident that Shelburne’s stance on the new republic was taken with an eye to both advancing the desired reconciliation with France and getting France to deal with other states in Europe. “It was a very deep game,” he told his wife (letter from Shelburne to Lady Shelburne, ca. January 1783, Bowood Archives). The compromises he struck were intended primarily to further Britain’s position with respect to France, even if they also concerned the new United States.

Plaque commemorating signing of the Peace of Paris on September 3, 1783. (Photograph by David K. Allison, 2016)

While he was able to effect an end to a war that had significantly reduced the British empire, he could do little to guarantee peace in the future, especially given the internecine warfare of British politics and the social and economic discontents in France that would boil up into the French Revolution. It would soon become clear that the governments of Britain and France could neither legislate and impose free trade for all nor keep the peace in Europe. Even so, Shelburne and Vergennes created at least for a few years an amity among the powers in Europe and a balance of power between large and small states. At the war’s end, amity and balance in Europe were just as important (to all but the treaties’ American architects) as American independence.

Since his days on the Continent as a military officer, Shelburne had felt that Britain should not be implacably opposed to France and its European allies. An uneasy, uncertain combination of idealism and realism, of philosophy and personality—traits shared by Shelburne and representatives of Britain, Europe, and America—shaped the entry of the new United States onto the world stage.