REWRITING THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION

Historical accounts of the American Revolution have varied in their coverage of the global dimensions of the war, in response to the intellectual and political trends of the era. As the nation approaches its 250th anniversary, reexamining the broader context of the conflict becomes increasingly important. —Editors

Americans who lived through the American Revolution understood that the war was being waged across the continent and around the world. News of the French-British Battle of Ouessant, fought off the coast of Brittany on July 7, 1778, reached attentive American ears shortly after the French admiral d’Estaing’s failed assault on Newport at the end of August. Britain’s capture of the Dutch Caribbean island of Sint Eustatius in early 1781 caused uproar among American merchants, but the fall of Pensacola in British Florida to Bernardo de Gálvez a few months later garnered warm congratulations from American leaders. And in 1782, the Pennsylvania State Navy gave a sloop of war the punning name Hyder Ally in recognition of the leader of the Kingdom of Mysore, Hyder Ali, in his fight against their common British enemy.

Americans who actually fought on the front lines could also see, hear, and feel the presence of the other nations involved in the conflict. The muskets they were issued were lighter than the traditional British “Brown Bess” they had used when they were still colonials, and the language of the metal stamping on their new guns revealed their origins. Guns from Liège bore the Latin motto Pro Libertate (For Liberty). Others came from France, Spain, and the Dutch Republic. American troops could hear the accents of the French and other European volunteers who fought side by side with them. Even the cloth of the American uniforms, from factories in Placencia, Spain, and Montpelier, France, felt different from the rough British weave to which they had been accustomed.

Given this international involvement, how did Americans come to rewrite the narrative of the Revolution in a way that leaves out the participation of these other nations, which—as the essays in this book have so clearly demonstrated—was crucial to the winning of independence? It was not the gradual amnesia of an aging nation; nor was it a sudden great forgetting of an undesirable past. History has always been the continuation of politics by other means, and the story of the American Revolution has been rewritten many times over the course of two and a half centuries to suit the political needs of each era. These retellings help us understand where the United States has been as a nation, what it is today, and what kind of nation it is to become.

Writing the American Revolution as a Work in Progress

Histories of the American Revolution were being written even as the early campaigns were being fought in the United States. Among them were several works by French writers who, soon after the 1778 Treaty of Paris had brought France into the war, rushed to interpret the unfolding drama not so much as an accurate description of events in America (the accounts were largely secondhand, from newspapers controlled by the monarchy) but as a canvas on which they could paint their own ideals of government.

For the playwright Pierre-Ulric Dubuisson, in Summary of the American Revolution (1778), and the philosophers Guillaume-Thomas Raynal and Denis Diderot in American Revolution (1781), the American war provided the perfect backdrop for showcasing their anticolonial views. Meanwhile, the lawyer Michel René Hilliard d’Auberteuil railed against the “excesses and decadence” of European governments in Historical and Political Essays on the North American Revolution (1781). American writers and politicians were outraged at what they saw as partisan screeds with a thin veneer of inaccurate history. Benjamin Franklin never acknowledged Dubuisson’s work, despite many entreaties from the author; Thomas Paine objected to Raynal’s statement that taxation was the cause of the Revolution; and Thomas Jefferson lamented, “If the histories of D’Auberteuil…can be read and believed by those who are contemporary with the events they pretend to relate, how may we expect future ages shall be better informed?” (Jefferson 1894: 439–40).

By contrast, Jefferson looked with favor on some later French works that provided a more realistic accounting of the war. Their authors—all noted historians and scholars—took great pains to show the global dimensions of the conflict. Pierre Charpentier de Longchamps’s Impartial History of the Military and Political Events of the Previous War in the Four Corners of the World (1785), as the title implies, looks at the conflict in each of the theaters of war: in fact, almost the entire third volume is devoted to the post-Yorktown battles in the Mediterranean, South Africa, India, and the Caribbean. Odet-Julien Leboucher underlined the importance of the coalition facing Britain by titling his book History of the Preceding War between Great Britain and the United States of America, France, Spain, and Holland (1787). And François Soulès, with the help of Jefferson himself for primary-source material, produced a sweeping four-volume work, History of the English-American Troubles (1787), that enters into the halls of power in Philadelphia, London, Versailles, and Madrid and takes its readers to battles around the globe.

Contemporary historians in the United States, who had witnessed events at first hand, also wrote about the American Revolution as a world war, though without the sweep and grandeur of Soulès’s account. William Gordon, who spent many weeks copying the personal files of George Washington, Nathanael Green, and others, produced the four-volume History of the Rise, Progress, and Establishment of the Independence of the United States of America (1788), whose final volume is largely given over to the events overseas that led to the final peace treaties, including a blow-by-blow account of the war in India. David Ramsay, who served in the South Carolina militia, notes the importance of the sieges of Pensacola and Gibraltar in the second volume of his History of the American Revolution (1789). The playwright Mercy Otis Warren, whose family fought in the war, produced the magisterial three-volume History of the Rise, Progress, and Termination of the American Revolution (1805), which gives proper weight to the combat overseas and its effect on the peace negotiations and was much favored by Jefferson. Two lesser-known writers also took pains to place these events in their appropriate context: Charles Stedman (a Loyalist officer in the war) in History of the Origin, Progress, and Termination of the American War (1794), and John Lendrum in A Concise and Impartial History of the American Revolution (1795).

The war may have been over, but at the end of the eighteenth century the Revolution was still a work in progress; as John Adams told Jefferson in 1815, the war “was only an effect and consequence” of the Revolution, and the final form of that Revolution was still being debated within communities and in the halls of government (Adams 1815). These historians were striving for accuracy based on their own experiences and observations, while still aiming to create an American culture and identity separate from their European origins. The tension between these two motivations would come to define the writing of the American Revolution in subsequent generations.

Writing the American Revolution as Living Memory

As the original participants in the Revolution began to disappear from the scene, accounts of the war began to shift away from historical accuracy and toward creating a patriotic narrative. The involvement of other nations in the conflict was largely erased from the historical record, with the exception of France’s role, and even that was included primarily because of the marquis de Lafayette. His prominence was assured in part by his grand tour of the United States of 1824–25 and his death in 1834, which cemented his reputation as “the hero of two worlds,” the focus of the French-American alliance, as is evident in the spike in references to him in English-language books. Spain, the Dutch Republic, and the Kingdom of Mysore were largely forgotten, as were any conflicts fought outside the thirteen colonies.

The marquis de La Fayette (as his name was then usually written) certainly played important roles during the war, first distinguishing himself at the Battle of Brandywine and then in independent command during the southern campaigns against General Charles Cornwallis. His exploits receive notice in the histories by Soulès, Gordon, Ramsay, and Warren in proportion to his activities. But so do the exploits of his fellow volunteer the Baron von Steuben and his countrymen Rochambeau and de Grasse, who actually receive more mentions in these earlier works than does Lafayette. By contrast, in Samuel Farmer Wilson’s A History of the American Revolution (1834), Lafayette garners thirty-two mentions, compared with seven for Rochambeau and twelve for de Grasse, both of whom were far more important to the American victory than the young marquis.

Mentions of La Fayette or Lafayette in English-language books published between 1770 and 1900. Lafayette’s death was a great boost to his fame. (Graph by author; drawn by Bill Nelson)

This glorification of Lafayette began as early as 1824. Jedidiah Morse’s Annals of the American Revolution appeared just as Lafayette was invited to visit the United States for its fiftieth anniversary. In a biographical appendix, Morse devotes nine pages to Lafayette’s story, more than twice as much space as he devotes to George Washington. Gálvez’s assault on Pensacola is captured in one sentence, and the campaigns at Minorca, Gibraltar, and in India are left out entirely. In Samuel Wilson’s book, Gálvez and Pensacola are left out completely, while Gibraltar merits just two lines, one of which refers to “the memorable defence by [British] General Eliot,” which was then promptly forgotten (Wilson 1834: 315). Even well-regarded authors such as Noah Webster (History of the United States, 1832) and John Frost (The History of the United States of North America, 1838) give scant attention to the role of foreign forces.

But the greatest injury by far to the understanding of the American Revolution as a world war came from the way children were taught. Two very popular works intended as school textbooks, Salma Hale’s History of the United States of America (1820) and Samuel Williams’s A History of the American Revolution (1824), were published as potted histories of the American republic and reprinted many times during the subsequent decades. They manage to economize the presence of foreign volunteers on American soil and the global nature of the war almost to the point of invisibility. Schoolchildren in the nineteenth century and into the twentieth would grow up learning that Lafayette was “among the chief actors” of the Revolution, but they could be forgiven if they were unaware of the presence of either Rochambeau or de Grasse, and they might never have known that places such as Pensacola and Gibraltar even existed.

Writing the American Revolution as Manifest Destiny

The tightening of the historical focus of the American Revolution to the events within the thirteen colonies, excluding the wider global context and the substantial presence of foreign volunteers in the Continental Army, accorded perfectly with the emerging ethos of American exceptionalism. As the United States expanded westward and began exerting its influence over the American hemisphere, narratives of the American Revolution, whether aimed at a scholarly audience or at schoolchildren, embraced the notion of manifest destiny. This ideology was nowhere more pronounced than in George Bancroft’s highly influential ten-volume History of the United States of America (1834–78), which served as the archetype for American history for generations to come.

Bancroft was a polymath who served as ambassador, secretary of the navy, and founder of the U.S. Naval Academy even as he was serially publishing and continually revising his history of the United States, which begins with the voyages of Leif Eriksson and ends with the peace negotiations of 1782. Although a consummate historian—he consulted hundreds of primary-source documents from European archives for his research—Bancroft was also an unabashed partisan of American exceptionalism: the notion that the progress toward a democratic republic was a uniquely American undertaking that derived not from soil or ancestry but from the nation’s distinctive ideologies of republicanism and liberalism, which were inimical to the older, corrupt monarchies of Europe. America was destined to become independent, so Bancroft’s million-word narrative explains, in order to leave those decaying roots behind. The obvious implication is that America was also manifestly destined to expand westward to the Pacific Ocean, spreading those values of liberty and equality.

John Gast, American Progress, 1872. Oil on canvas. Gast’s painting has become a widely recognized symbol for the idea of the United States’ manifest destiny. Here, personified as a woman in white, Manifest Destiny leads American pioneers westward toward the Pacific. (Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-DIG-ppmsca-09855)

Bancroft was also quite partisan when it came to the overseas aspects of the Revolutionary War. Throughout volumes 7–10, devoted to the war, Bancroft admires French assistance to the United States, from the early materiel aid of Beaumarchais to the combined campaign at Yorktown. He describes the French foreign minister, the comte de Vergennes, as “wise,” “able,” and “honorable,” and even notes the bravery of the French engineer François-Louis de Fleury at the battles of Brandywine and Stony Point. He especially fawns over Lafayette—whose portrait graces the frontispiece of volume 9–and mentions him more often than Rochambeau and de Grasse combined. The Dutch Republic gets several nods, and Hyder Ali a single line.

But he reserves his particular enmity for the Spanish. Bancroft, a diplomat, was writing his History at a difficult period in Spanish-American relations. Each side had good reason to mistrust the other. Spain’s loss of much of its American empire, combined with the Monroe Doctrine, which extended American influence over the hemisphere, meant that the two nations were continually elbowing each other over such matters as Cuban independence, influence in Santo Domingo, and intervention in Mexico. America’s distrust of Spain as a threat to its manifest destiny is reflected in Bancroft’s historical narrative: he heaps venom on Spanish actions and motives at every opportunity. Don José Moñino y Redondo, the Count of Floridablanca, in charge of Spain’s foreign affairs and effectively Vergennes’s counterpart, receives the brunt of Bancroft’s attacks; he is “devoured by ambition,” “irritable,” full of “intrigues”; he “dissimulates,” “cavils,” and hates the idea of American independence (Bancroft 1834–78: 10: 189). More than any other factor, Bancroft’s dismissal of the Spanish involvement in the Revolutionary War is why Americans came to forget how critical it was to victory.

Other contemporary histories were shaped in the same mold. Richard Hildreth, who professed accuracy and abjured the kinds of “sermons and Fourth-of-July orations” (Hildreth 1849–52: 1: iii) that Bancroft was accused of, nevertheless glorifies Lafayette and gives the Spanish short shrift in his six-volume History of the United States of America (1849–52). John Ludlow’s War of American Independence (1876) labels Lafayette the “foremost of French heroes” but notes only that Pensacola “capitulated” to the Spanish, without ever identifying the Spanish heroes of that important battle. Children’s textbooks also repeated this pattern; Jacob Abbott’s American History (8 vols., 1860–65) states that of all the French naval and military officers, Lafayette offered the most valuable services; the Spanish do not even rate a mention.

Writing the American Revolution as a Rising Power

“By the end of the nineteenth century,” notes Ray Raphael in Founding Myths (2004), “romantic stories of the nation’s founding had been fine-tuned and firmly implanted in the mainstream of American culture.” The post–Civil War nation was finally entering the throes of industrialization that had already transformed Britain from a nation of shopkeepers into the workshop of the world. America was beginning to flex its diplomatic and military muscles, and the historical narrative of American exceptionalism perfectly suited this age. Among its proponents was John Fiske, described as the “Bancroft of his generation” (Raphael 2004: 294). In 1889, he wrote The War of Independence, a short (250-page) introductory text that was intended for students but came to wield substantial influence on the American psyche. Fiske, like Bancroft, completely ignores the Spanish and does even more to pare down the presence of foreign troops, mentioning only those of Lafayette; Rochambeau, in Fiske’s telling, was not even at Yorktown. And the subsequent battles at Gibraltar and Cuddalore never happened. This was in keeping with the received narrative, for, as Raphael points out, “Popular historians…simply decreed that their histories ended at Yorktown. There, the Americans won and the British lost. The Americans celebrated, while the British, following Lord North, declared, ‘Oh, God! It is all over.’ End of story” (Raphael 2004: 258). This narrative certainly contributed to the famous account of America’s arrival in France during the First World War, marked by General John J. Pershing’s chief of staff, Charles Stanton, declaring, “Lafayette, we are here!,” as if the sole reason America went to war with Germany was to repay its debt to the marquis.

General John J. Pershing and staff at Lafayette’s tomb, Picpus Cemetery, Paris, July 4, 1917. (Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-B2-4281-1L)

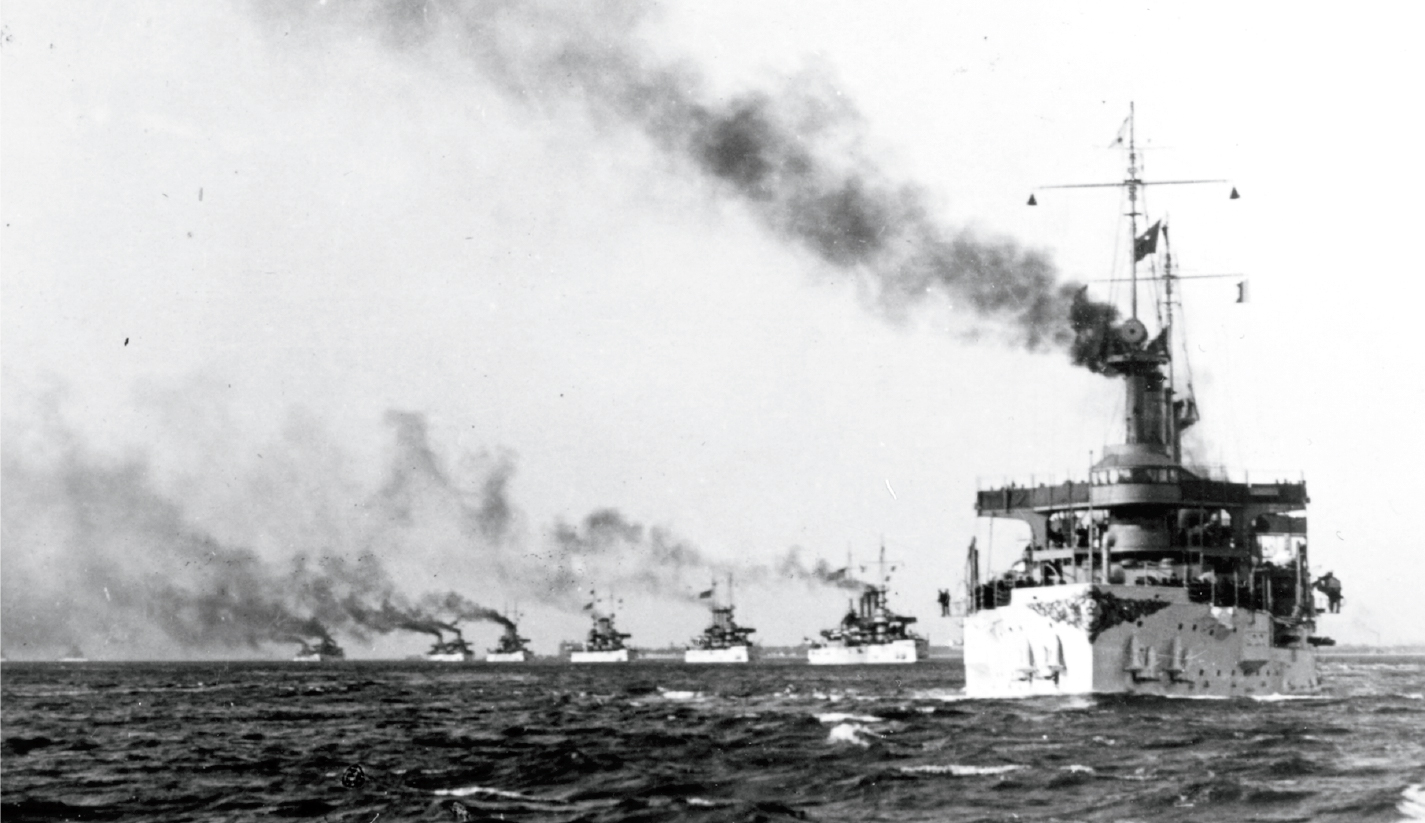

As the increasingly self-confident nation, which could send the Great White Fleet of naval ships around the world, passed its century mark, less one-sided accounts appeared. Edward Channing, whose last volume of the epic six-volume History of the United States (1905–25) garnered a Pulitzer Prize for history, is a bit more generous in his treatment of Spain and reinstates Rochambeau at Yorktown. He also makes the point that by 1782, the fact that British military strength was “dissipated” around the world was a factor in Britain’s coming to the peace table. Historians also began drawing attention to hitherto-ignored aspects of the international scope of the war. Edwin Stone’s Our French Allies (1884), Thomas Balch’s The French in America during the War of Independence (1891), and Joachim Merlant’s Soldiers and Sailors of France in the American War for Independence (1920) describe French and American operations from Newport to Yorktown, while biographies of individual French participants also began to appear. Friedrich Edler’s The Dutch Republic and the American Revolution, published in 1911, remains the only full-length treatment of the subject. And for the first time, a proper accounting of Spanish operations in the South was given in John Caughey’s Bernardo de Gálvez in Louisiana (1934).

The Great White Fleet under way off Hampton Roads, Virginia, 1907–09. This round-the-globe voyage by a U.S. naval battle fleet demonstrated to other nations that the United States was now a rising power in world affairs. (Naval Historical Center, photo no. NH 100349)

Writing the American Revolution as a Superpower

For most of the twentieth century after World War II, America was the dominant global power, but it was in constant conflict with the other great power, the Soviet Union. The experience of World War II, the possibility of war with the Soviet Union, and actual fighting against its proxies in Korea and Vietnam led to the wholesale rethinking of the American armed forces. With the increasing professionalization of men and women in uniform, there was greater emphasis on using history to teach critical thinking. America’s expanded military role around the world meant that “lessons learned” from current and previous conflicts took on new significance in both the uniformed services and in academia. Histories of the American Revolution now took a sharp turn toward its military and strategic aspects. There was certainly much to learn from that war: how to fight in an asymmetric conflict, the need for popular support, the importance of a navy, and the value of alliances and coalitions.

One of the first postwar historians to take this military and strategic perspective was Howard Peckham, in The War for Independence: A Military History (1950). Among several achievements in this short (220-page) volume is the recognition of the strategic importance of Gálvez’s campaign: it “undermined the British western scheme” and prompted General Henry Clinton to abandon Newport. In 1964, the British historian Piers Mackesy, although focusing on the strategic and political issues behind Britain’s stumbling efforts to retain an empire, brought a much-needed global perspective to his War for America, 1775–1783. Its breadth of vision makes this one of the most important histories of the war even today. In a similar vein, John Alden’s History of the American Revolution (1969) balances the military, diplomatic, and political aspects of the war and takes note of the strategic importance that France and Spain placed on invading Britain and besieging Gibraltar. Perhaps the best treatment of the American Revolution as a world war was undertaken by the team of Richard Ernest Dupuy, Gay Hammerman, and Grace P. Hayes in The American Revolution: A Global War (1977), which brought a renewed emphasis on the naval battles around the world: the section on the campaigns in India and Ceylon alone is worth the price of the book.

It was also during the later twentieth century that comprehensive histories of the coalition nations began to appear. The American Revolution and the French Alliance, by William Stinchcombe (1969), explains how the two sides came to develop a cautious cooperation, despite having been on opposite sides of the Seven Years’ War not long before. Jonathan Dull’s The French Navy and American Independence (1975) not only stresses the war’s naval battles and strategies but also reveals the diplomatic maneuverings of the French and Spanish courts that had been, until recently, unknown to Americans. And Barbara Tuchman’s The First Salute (1988), while not a comprehensive history per se of the Dutch Republic’s involvement, nevertheless places front and center its fight with the British as a crucial part of the war.

Writing the American Revolution in the Age of Globalization

The fall of the Berlin Wall, in 1989, left the United States as the world’s only superpower, attempting to manage a chaotic, newly interconnected world. Americans began to reflect on what the United States represents as a nation and what it means to be an American today. Many of the recent histories of the American Revolution have undertaken more introspective analyses of the era, questioning received wisdom as to the causes, actions, and consequences of the war. Gordon Wood’s The Radicalism of the American Revolution (1991) and The American Revolution: A History (2002) are leading examples of this inward focus, stressing the consequences of the Revolution for the lives of slaves, women, and the common laborer, while leaving aside the larger global context.

Other histories have been more international in their outlook, showing that the networks of alliances and coalitions back then have echoes today. In 2002, Thomas E. Chávez published the first comprehensive examination of Spanish participation in the war, Spain and the Independence of the United States: An Intrinsic Gift. John Ferling’s Almost a Miracle: The American Victory in the War of Independence (2007) pays particular attention to the French alliance and the Anglo-Dutch wars, less to Spanish involvement. And Richard Middleton’s The War of American Independence (2012) not only stresses the importance of the French alliance but also gives over entire chapters and subchapters to Spanish and Dutch motives and actions.

Writing the American Revolution on the 250th Anniversary of the Nation

The American Revolution began as a civil war between English colonists and their British rulers, confined to a small strip of coastline in North America. It soon pulled in American Indian nations, free and enslaved people of color, and Spanish and French inhabitants in the South on the Gulf Coast and along the Mississippi River. By its end, the American Revolution had turned into a global war involving six separate nation-states fighting across five continents and two vast oceans. As the authors in this volume have so clearly shown, both in their essays here and in their numerous published works elsewhere, the American Revolution was “the History of Mankind for the whole Epocha of it,” as John Adams so astutely noted (Adams 1783). The global nature of the Revolution was, in fact, a reflection of what the American nation was at its inception and is today—the centerpiece of international efforts for a common good.

The United States is approaching its 250th anniversary in 2026 in a world that is increasingly coming to resemble that of 1776. America’s position as the single preeminent superpower is giving way to a multipolar world in which regional spheres of influence are dominated by other powers—not just Russia and China but also blocs of nations in Europe and South Asia. Global politics is marked increasingly by the struggle for a balance of power among the United States and these nations, much as the American Revolution was really part of the balance-of-power struggle among Britain, France, and Spain. The fabric of the nation is today as diverse as it was then, especially with the growing number of citizens of Hispanic and Latino origin. And the influence of immigration, international travel, and trade is now greater than at almost any time in U.S. history.

History is not only the continuation of politics by other means: it is also the means by which we come to understand who we are and who we will become. The study of the American Revolution will continue to offer fresh interpretations of our nation’s origins and its relationship with the world to help guide the way we create our future.

Former allies and enemies who are now an international coalition securing the peace: Dutch, Spanish, British, American, and French warships operating together in Combined Task Force 150, Gulf of Oman, May 6, 2004. (U.S. Navy 040506 N7586B 141)