Sassanian society was broadly ordered into Arteshtaran or warriors, scribes, priests, and commoners. Of the warriors, it was the elite cavalry or Savaran who held the position of honor. Each Savaran unit seems to have had its own Drafsh (banner). Membership in such units and other important posts was generally reserved for individuals of Aryan ancestry. These encompassed three general categories.

First of these were the members of the seven top families of Persia, the first of which was the House of Sassan. The other six had Parthian roots. These were the Aspahbad-Pahlav (Gurgan region, northern Persia), Karin-Pahlav (Shiraz), and Suren-Pahlav (Seistan, southeast Persia), Spandiyadh (Nihavand region, close to Kurdistan), Mihran (Rayy, close to modern Tehran), and Guiw.

Leg of a throne shaped into a griffin. (Louvre Museum, Paris)

The second category comprised the Azadan upper nobility. Confused by Greek sources with “freemen,” the Azadan were descendants of the original Aryan clans that had been settled in the Near East since the times of the Medes or earlier. They could be traced back to the Azata nobility of Achaemenid times. It was the Azadan who formed the core of the Savaran. The third category was the direct result of Khosrow I’s reforms, which allowed for the lower nobility, the Dehkans, to enter the ranks of the Savaran.

The most famous of the Savaran were the Zhayedan (Immortals), who numbered 10,000 men and were led by a commander bearing the title Varthragh-Nighan Khvadhay. This unit was in evidence from the early days of the Sassanians and was a direct emulation of the similar unit that fought for Darius the Great. It is highly probable that the uniforms and insignia of this unit reflected Achaemenid tradition. As a Savaran force, their task was to secure any breakthrough, and they were often held in reserve, entering battles at crucial stages.

Another Savaran prestige unit was the Royal Guard or Pushtighban, led by a commander with the title of Pushtighban-Salar. The Pushtighban numbered perhaps 1,000 men. In peacetime, the Pushtighban was stationed as a royal guard regiment in the capital, Ctesiphon. Cavalrymen who particularly distinguished themselves by bravery in battle were incorporated into the Gyan-avspar (those who sacrifice their lives), also known colloquially as the Peshmerga.

By the time of Khosrow II (r. AD 590–628), a number of other prestige Savaran units had appeared. Two of these were the Khosrowgetae (Khosrow’s Own) and the Piroozetae (The Victorious Ones), who were apparently royal guard units. An interesting account in the Khuzistan Chronicle notes that during the siege and conquest of Dara in 604, Khosrow II was rescued from a potential trap, a noose which was cut by one of his elite bodyguards named Mushkan, who was most likely a member of the Khosrowgetae or Peroozetae. These units are again mentioned in the wars of 603–28 when Khosrow II sent the Khosrowgetae and Peroozetae to General Shahraplakan in Caucasian Albania (present-day Republic of Azerbaijan). Another prestige unit contemporary to Khosrow II was a large Spah (army) of 50,000 Savaran known as the Golden Spearmen, supplied to General Shahin by his colleague Farrokhan Shahrbaraz (Theoph. A.M. 6117, 315.2–26).

Finally, it would seem that officers leading other branches of the army may themselves have been members of the cavalry elite. The infantry forces that invaded Yemen were led by a Savaran officer by the name of Vahriz.

The Sassanians inherited the Parthian system of military organization; however, their system was to become far more sophisticated than its predecessors’. The early Sassanian Spah (standing army or military) had much in common with its Parthian equivalent. In general, three designations were used: (1) Vasht (Parthian Wast), a small company; (2) a larger unit of perhaps 1,000 men known as a Drafsh, with its own banner and system of heraldry; and (3) a large regular division known as a Gund. The Gund was led by the Gund-Salar or general. A corps in Parthian times seems to have numbered 10,000 men, as seen by the forces of general Surena who defeated Crassus’ Roman legions at Carrhae in 53 BC. The size of a regular Sassanian army was probably 12,000 men. The pride of the Sassanian Spah were the Savaran.

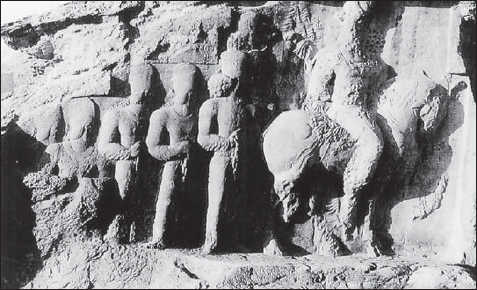

Shapur I. The four warriors behind the king are most likely from a royal Savaran unit. (Author’s photo at Naghsh-e-Rajab)

In Parthian times, the proportion of heavy lance-armed cavalry in comparison to horse archers was one to ten – this proportion was to radically shift in favor of lancers by the early Sassanian era. This meant that the importance of the lancer increased such that by the rise of the early Sassanians, the heavy armored lancer had become the dominant feature of Iranian warfare, with horse archery in decline.

Unlike their Hellenic adversaries, the Achaemenids used the decimal system to organize their Spada (Achaemenid for army). It is highly probable (though not certain) that the Sassanians used the decimal system as well, this being suggested by titles such as Hazarmard (thousand-man) and Hazarbad (chief of a thousand) or references such as “Gusdanaspes who was captain of a thousand men in the army of Shahrbaraz” (Theoph. A.M. 6118, 325.10).

The Vuzurg-Framandar (Great Commander) managed the affairs of state, headed by the monarch. When the monarch was away in battle, the Vuzurg-Framandar would take over state functions in Ctesiphon. He could become the commander in chief and was entrusted to engage in diplomatic negotiations, especially after a war or battle. The regular commander in chief of the army and Minister of Defense was the Eran-Spahbad, who was also empowered to conduct peace negotiations. He also acted as Andarzbad or counsel to the king. The posts of commander of the Savaran, known variously as Aspbad and Savaran Sardar, and of chief instructor of the Savaran, known as Arzbad-e-Aspwaragan, were also held by members of the elite. The post of Savaran Sardar was held by a member of the Mihran-Pahlav family during Julian’s invasion in 362.

A Sassanian Ram symbol. (Louvre Museum, Paris)

It is difficult to specifically relate actual family names to other important military posts, however the Suren and Mihran names occur frequently. Roman sources would sometimes mistake the names of nobility with actual military titles. A typical example of this is the Roman reference to “the Suren” during Julian’s invasion of Persia, when in fact “Surena” referred to one of the seven major families.

There is some confusion between the terms Spahbad, Marzban, Kanarang, Paygospanan, and Istandar. A Spahbad was an army general who could also be a military governor. His assistant was known as the Padgospan. The Spahbad’s officers were the Padan. Battlefield commanders were designated as Framandar. It is not exactly clear how to distinguish the Spahbad from the Marzban. Some accounts blur the distinctions between the two, while others suggest that the Spahbad was a general-diplomat empowered to conduct negotiations by the king when so ordered, and the Marzban was strictly military, as implied in his role of frontier marches commander or ruler of an important border province. Kanarang, an east Iranian term, is least clear, apparently the title of the Marzban of Abarshahr in Central Asia. The term Paygospanan seems to refer to provincial military commanders. The Istandar was the leader of an istan (province or district/area within a province).

A number of other Achaemenid-type military terms appeared by the mid-Sassanian era. A term reserved for warriors displaying great bravery in battle is Arteshtaran-Salar (Chief of Warriors), a term of Achaemenid origin. Warriors honored with such a ranking include General Siyavoush and Bahram Gur. Argbadh was the highest military title and was held by royal family members. A less defined title is the rank of Rasnan. Certain Azadan families were entrusted with specific duties, such as the Artabid, who crowned each new monarch. A group of Vuzurgan or grand nobles would also be present at coronation ceremonies. The Zoroastrian Magi (Moghan) and priests (Mobadan) played a very important role in society and they accompanied the soldiers to battle. The chief of the clergy or Mobadan Mobad was a very important personage at court. Rock reliefs often show Magi accompanying the king and his warriors.

The reforms attributed to Khosrow I (r. AD 531–79) led to four major changes. First, the lesser nobility, the Dehkans, were admitted into the ranks of the Savaran, resulting in a larger manpower base for the cavalry forces. Second, the domestic ranks of light cavalry, especially horse archers, dramatically decreased. Foreign contingents were actively recruited to fulfill the latter role. The Savaran were now treated as state officials and were to receive a regular salary as well as subsidies. In addition, they were to receive their armaments, equipment and horses directly from the state. Third, official inspections evident since the early days of the dynasty now became more thorough, at times lasting up to 40 days. Even the king was not exempt from this process.

The fourth and final change was the removal of a single commander in chief (Eran-Spahbad) in favor of four field marshals or Spahbads. The previous four Marzbans were now subordinated to the respective Spahbads. Each Spahbad was to guard one sector of the empire. The Spahbad of the east guarded Khurasan, Seistan (Sakastan), and German (Kerman). The southern Spahbad watched over Persis, Susiana, and Khuzistan as well as the long coastline of the Persian Gulf. The northern Spahbad defended Media, Kurdistan, Azerbaijan, and Arran, as well as vital passes of the Caucasus (e.g. the Derbend Pass). The Spahbad of the west was entrusted with the defense of the most important economic, trade, and agricultural area, the one most vulnerable to Roman attack: Mesopotamia (modern Iraq; from Iranian Arak meaning “the lowland”). Each Spahbad was also responsible for the recruitment and levying of his troops. Theoretically, each Spahbad would have one quarter of the entire army at his disposal, but in practice this probably did not take place.

This metalwork plate shows Khosrow I surrounded by nobles of the elite. (State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg)