There has been a consistent pattern of costume and dress among Iranian peoples since antiquity. The typical Iranian riding costume of trousers, leather boots, tunic, and cap has shown a remarkable continuity across time and geography. The same basic pattern provided the basis for the Iranian costumes of the Central Asian Scythians and Sarmatians, as well as the Parthians and Sassanians of Persia. In Sassanian Persia, the traditional riding costume became almost synonymous with ceremonial attire. This meant that in addition to battlefield dress, there were possibly a variety of court costumes worn by the Savaran, noblemen, and military officials. These would most likely vary according to rank and clan.

Uniforms had been a standard aspect of the armies of Persia since the Achaemenean Empire. Sekunda (1992) has noted that uniforms for armies were first introduced in Achaemenean Persia and were only later adopted by the classical Greeks. For the design of uniforms, the early Sassanians looked to the ancient Achaemeneans for inspiration. This is confirmed by Julian (III, 11–13.30, pp.132–8, Bidez), who notes that Sassanian warriors “imitate Persian fashions…take pride in wearing the same…raiment adorned with gold and purple…their king [Shapur II?]…imitating Xerxes.” Members of the upper Aryan nobility (Azadan) wore distinctive badges of honor and specialized dress that were marks of their status.

There was a great deal of continuity between Parthian and Sassanian times in terms of costume. This is because many of the noble clans of the Parthian era continued to be well represented, with many of their articles of dress continuing into Sassanian Persia. One example is the Parthian tunic, which was Scythian in style, with the right tunic breast laid over the left, a “V”-shaped neck line and long sleeves. The north Iranian and Parthian embroidered trousers and tunics with long sleeves were adopted in Europe by the later Roman army as well as by eastern Germanic tribes (Boss, 1993, p.56).

Among the Parthians and early Sassanians colors of trousers had usually been blue, red, and green. Since the Sassanians were keen to emulate the fashions of the Achaemeneans, colors such as brown, red, crimson, and varieties of purple became increasingly common. A typical European portrayal of Iranian costume is that of the mosaic of San Apollinare Nuovo in Ravenna which shows the Three Wise Men, or Magi, of Persia. They wear tight Persian trousers with cape-like coats. These types of costume continued up to the reign of Khosrow II, by which time a strong Central Asian influence becomes evident in Sassanian dress.

Sassanian-style kaftan found in the Caucasus, late to post-Sassanian period. (State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg)

Much of Byzantine dress shows eastern or Persian influence, especially in the color and pattern of costume designs. It is possible that Diocletian introduced the Persian style of gem-studded costume to the imperial court of Byzantium (Arberry, 1953). Kondakov (1924, p.11) has noted that the Byzantines borrowed much of their system of uniforms from the Sassanians. Ironically this may have mainly occurred close to the end of the Sassanian era during the catastrophic Byzantine–Sassanian wars of 602–22.

Each Savaran and elite unit had its own battle standard and coat of arms known as the Drafsh. Drafsh could either be flown as banners or worn as insignia by the troops. Since Achaemenean times, field armies in Persia had been using a type of tamga system. The Sassanians directly inherited the Parthian Drafsh system, and many of these were retained as battle standards by the Parthian noble houses. Tamga (symbolic, clan or family signs) were also used extensively by Iranian nomadic peoples such as the Alans and Sarmatians (see Men-at-Arms 373: The Sarmatians 600 BC–AD 450).

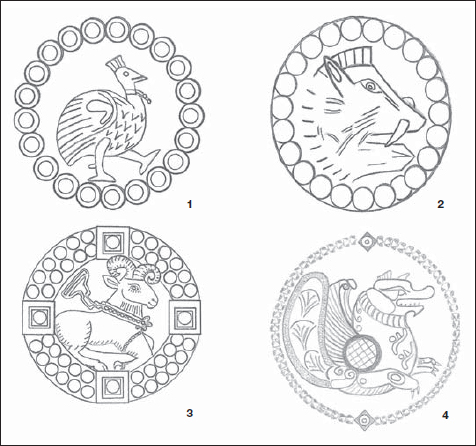

Medallions: (1) Frashamurw. (2) Waralz or Baraz. (3) Warrag. (4) Senmurv. (Kaveh Farrokh, 2004)

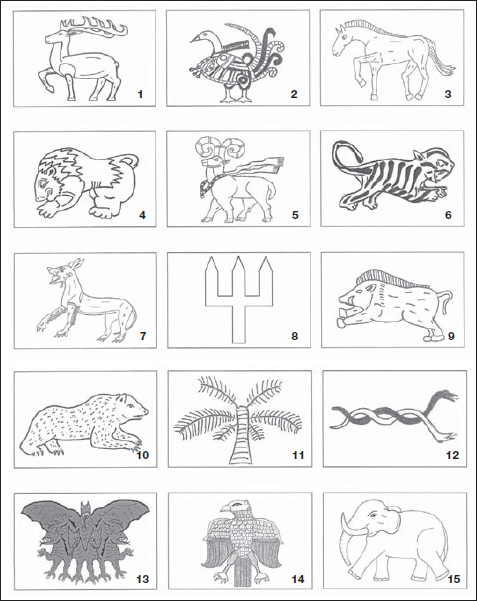

Coat of arms insignia: (1) Ahug or Gawazn. (2) Tardarw. (3) Asp Ziball. (4) Shaigr. (5) Warran. (6) Babr. (7) Gurg. (8) Tritha Zarduxsht. (9) Waralz or Baraz. (10) Xirs. (11) Draxt. (12) Garzag. (13) Haftan-bokht. (14) Humay. (15) Pill. (Kaveh Farrokh, 2004)

Knowledge of Sassanian heraldry is derived mainly from examples of Sassanian rock reliefs and some Roman references (e.g. Persici Dracones). The post-Sassanian Shahname epic of Firdowsi provides a vivid description of various types of Drafsh, which are noted by Christensen (1944, p.211) as being derived from Sassanian sources. A recent find east of the Aral Sea has yielded at least 18 seal stones, which provide additional sources of information.

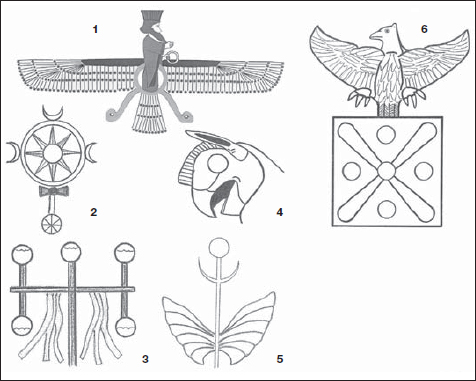

The most prestigious national banner was the Drafsh-e-Kaviani. Legend ascribed the banner to a certain blacksmith known as Kaveh who united and liberated the Aryans by overthrowing their evil serpent-worshipping oppressor, Zahak. In actuality, this banner most likely originated in Parthian times as a royal battle standard. The largest version of this standard, which was richly embroidered with jewels, silver, and gold, measured roughly 16 by 23ft.

There were a very large number of Drafsh designs with boars, tigers, gazelles, wolves, as well as mythological beasts. The Draco (dragon) flags were especially popular, as they were among northern Iranian (Sarmatian) peoples. It is also known that as an attack was to begin, a Drafsh the color of fire (or possibly of flame design) would be displayed (Ammianus, XX.VI.3.). The Savaran would display their Drafsh on a cross-bar or pole, however tunics and shield bosses could also display these. An example is the 4th-century Shir-Eiran (Lion of Persia) shield boss in the Museum of London.

Banners: (1) Zarduxsht. (2) Possible Mithras symbol – Pahlavi term unknown. (3) Possible commander in chief – Pahlavi term unknown. (4) Bashkuch. (5) Possible Parthian banner – Pahlavi term unknown. (6) Drafsh-e-Kaviani. (Kaveh Farrokh, 2004)

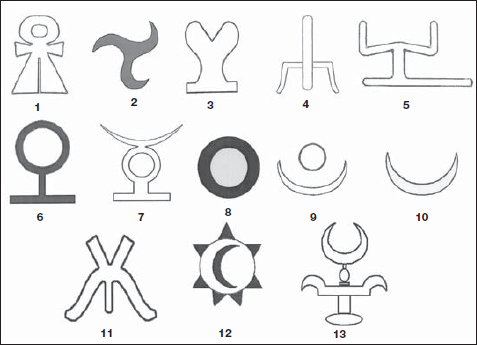

As mentioned before, the seal has its origin in the north Iranian tamga, which was evident in Achaemenean times. The tamga became the neshan, or seal, in Persia. Seals were worn by Savaran, military personnel, and nobility. Each noble family seems to have had its own neshan. These could be worn as medallions, or branded on horses. The neshan of the House of Sassan can be seen consistently from the rise of the dynasty with Ardashir I (AD 180–239) to Khosrow II. Rock reliefs of the aforementioned rulers at Firuzabad and Tagh-e-Bostan show their horses branded with these neshans. Various other unique neshan also seemed to appear, such as the wild boar of Khosrow I or the neshan of Princess Boran. Important court officials often carried symbols of their functions. Examples included the squire of a knight who carried a bow, a cavalry regiment commander with a horseshoe, or the polo-master with a polo stick. In time these came to be represented more symbolically. The Persian term rang was used to designate rank, status, or position.

Shoulder-type military decorations are also seen among the Sassanians. Colored shoulder tufts are described in Maurice’s Strategikon and “have a Persian ancestry” (Boss, 1993, p.66). Late Sassanian costumes in Tagh-e-Bostan show surprisingly modern-looking rectangles reminiscent of epaulettes on the shoulders of today’s military officers. Colors also signified rank, status, and perhaps religious affiliation. Color combinations such as yellow and green or black and red can be traced as far back as Achaemenid times (see Elite 42: The Persian Army 560–330 BC).

Neshan: (1) Ardashir I, Firuzabad. (2) Unknown clan or military unit (see Christensen). (3) Royal knight, Firuzabad. (4–5) Unknown Sassanian clans or military units (see Christensen). (6) Ardavan, Firuzabad. (7) Shapur, Firuzabad. (8) Xwar (sun) disc on flagpoles and swords. (9) Nobleman, Naghsh-e-Rustam. (10) Unknown Sassanian clan or military unit (see Christensen). (11) Hormuzd II. (12) Possible Mithras symbol. (13) Shapur I. (Kaveh Farrokh, 2004)