The paighan were recruited from peasant populations. Each paighan unit was commanded by an officer called Paighan-Salar. Paighan were used to guard the baggage train, serve as pages for the Savaran, storm fortification walls, undertake entrenchment projects, and excavate mines. They were mainly armed with the spear and shield. In battle they would typically cluster close to each other for mutual protection. Their military training, combat effectiveness, and morale were generally low. Their numbers actually swelled the army when siege warfare was involved. The Chronicon Anonymum (66, 203.20–205.7) reports Khosrow Anoushirvan’s forces as being composed of a total of 183,000 men. The majority (120,000) were paighan: farmers and laborers recruited to do siege work. There were 40,000 combat infantry and only 23,000 cavalry.

The Medes were one of the first Iranian peoples to enter and settle the Near East. Their descendants include Kurds, as well as the now Turkic-speaking Azerbaijanis (known to the Romans as Media Atropatene). Though Mede cavalry is depicted in Assyrian reliefs, the Medes’ infantry played a prominent role in battles against the Assyrians. The Medes were an essential and integral part of Persia both culturally and militarily; however, their most spectacular victory has gone unnoticed by most historians. A mixed Parthian and Median force defeated the Roman general Marc Antony near Tabriz in Media Atropatene. In 36 BC Marc Antony crossed the Euphrates and arrived in Media Atropatene with a force of 100,000 men. According to Plutarch, Antony lost close to 40,000 men in the subsequent battle.

The Medes supplied high-quality slingers, javelin-throwers, and heavy infantry for the Sassanian Spah. The Spah made use of heavy infantry from the early days of the dynasty. Referring to Ardashir’s attack on Roman Mesopotamia, Herodian (VI, 2, 5 6) notes that the Sassanians “overran and plundered Mesopotamia with both infantry and cavalry.” The Roman opinion of Sassanian infantry is negative, viewing them as a mass of poorly equipped and incapable serfs. This may not be accurate since the Romans may have been mistaking the paighan with the separate regular combat infantry.

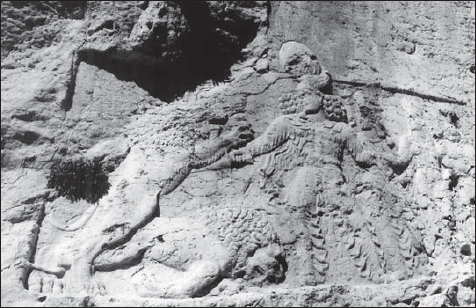

Bahram II slays lions defending his queen, Shapurdukhtat. Kartir stands between Bahram and the queen. (Author’s photo at Sar Mashad)

The typical Sassanian infantryman of the early period would most likely be equipped in the manner seen at Dura Europos with a two-piece ridge helmet, long coat of mail, and the Achaemenean-style leather-osier shield. By the time of Julian’s invasion of Persia, Persian heavy infantry are described by Ammianus Marcellinus as highly disciplined and “armed like gladiators.” By this time, it is possible that the Sassanians were trying to copy the Roman legionary or trying to revive the Achaemenean infantry tradition. Spearmen are sometimes reported as capable of facing Roman legionaries. In battle, the heavy infantry initially stood behind the foot archers who would fire their missiles until their supplies were exhausted. The archers would then retire behind the ranks of the heavy infantry, who would engage in hand-to-hand fighting.

It is interesting that the infantry were seen as reliable enough to be placed in the center behind the Savaran. In practice, heavy infantry could advance in coordination with the Savaran. Nevertheless, the Sassanian infantry, as a whole, could never fully match the Romans and later Byzantines. The Hellenic and Roman tradition of this combat arm was more extensive than the Sassanian; the Iranians excelled at cavalry warfare and archery.

By the later stages of the dynasty, a new breed of heavy infantry appeared from Northern Persia: the Dailamites. These became Sassanian Persia’s finest infantry. Roman sources have spoken highly of the Dailamites’ skill and hardiness in close-quarter combat especially with the sword and dagger (see Agathias 3.17). They often went face-to-face against the best of Rome’s legionaries. They also gave a good account of themselves in an invasion of Yemen, in which 800 of them were led by a Savaran officer by the name of Vahriz.

Sassanian medallion. (Louvre Museum, Paris)

Weapons of the Dailamite included the battle-axe, sling, dagger, and heavy sword. The late Sassanian Dailamite infantry may well have used the same “P”-mount suspension for their swords as the Savaran. A large number of finds in Northern Persia have been of swords of the late Sassanian type with the Varanga feather decoration. Bows were also used effectively, as attested to by a relatively rich find of archer fingercaps in northern Persia. Another interesting missile weapon was a short two-pronged spear. This could be used in hand-to-hand combat or be hurled in the manner of the Roman javelin. Shields were brightly painted, in accordance with a Dailamite tradition which survived into Islamic times.

The invading Arabs of the 7th century proved unable to subdue the Dailamites. Whenever Dailamites joined the Islamic cause, they were welcomed eagerly by the Arabs into their ranks, who would often pay them more than Arab troops.

Foot archers were highly regarded. Archery was seen as key to winning battles and training in archery was heavily emphasized. Foot archers were used in both siege work and set-piece battles. In siege warfare, towers were often erected against enemy forts. Archers would climb the ladders and fire into enemy strongholds, while archers on the ground would pour withering fire onto the defenders, reducing their ability to repel an assault.

On the battlefield, powerful volleys of arrows would be launched until supplies of arrows were exhausted. Foot archers had one main function: softening up the enemy before the decisive strike of the Savaran. Specifically, they were to support the Savaran by releasing, with deadly precision, as many volleys of missiles as possible. The objective was to damage enemy formations of archers and infantry so that they would be unable to withstand the Savaran attack. In defense, archers were entrusted with stopping enemy infantry or cavalry attacks.

The Romans learned to offset Persian archery by making a determined rush into Sassanian ranks, where they could bring their excellent close-in fighting skills to bear. Although not always effective, this tactic sometimes achieved success. The main contest here was between the speed of the Romans’ charge versus the quantity of missiles Sassanian foot archers could fire before the Romans closed the gap.

Each archery unit was led by a Tirbad officer. The Tirbad organized archers into companies so that one group would relieve the other while still maintaining a rapid rate of fire. In the 18th century this tactic was adapted by the Lurs of western Persia to rifle technology when they defeated Pathan invaders from southeastern Afghanistan.

The large rawhide wickerwork shields of late Sassanian foot archers were reminiscent of Achaemenean days. The foot archers’ tactic was almost identical to the Medo-Persians of old: advancing together and producing a deadly and overwhelming hail of arrows. Another tactic may have been to advance close to Roman lines with the Savaran in escort. This would allow them to get closer to Roman lines and be afforded the safety of their heavy cavalry. Interestingly, the foot archers could shoot backwards when retreating, resembling the Parthian shot of the horse archers. Finally, mention must be made of a very small elite contingent of royal foot archers of 100 men, whose task was to defend the throne to the death.

One battle in which the foot archers distinguished themselves was at Anglon, Armenia, in AD 542. A Byzantine force of 30,000 troops was soundly defeated by a force of 4,000 Sassanians under Nabed. Nabed lured the Byzantines into the town after they broke through a weak screen of defenders. A Stalingrad-style ambush awaited the huge Byzantine force. Archers hiding in cabins and other carefully prepared positions poured volleys of missiles from multiple directions at the pursuing Byzantines. It is very likely that the archers included a number of dismounted cavalry. The speed, accuracy, and volume of arrows made a proper counter-response virtually impossible. The Byzantine attack transformed into a panic flight toward the frontier. Many of the fleeing soldiers were captured. The end result was a resounding Sassanian victory, inflicting heavy losses on the Byzantines (Procopius II.25.1–35).

Armenians were accorded a status equal to the elite Savaran (see Men-at-Arms 175). In fact, the equipment and regalia of Armenian cavalry were identical to the Savaran. Pro-Sassanian Armenian cavalry units fought under Sassanian banners and were allowed to enter the royal grounds of Ctesiphon. The king would then send a royal emissary to inquire about the state of Armenia – this was repeated three times. The day after, the king would honor the Armenians by personally inspecting their troops in a military review. The Armenian general Smbat Bagratuni was accorded particular honor by King Khosrow II. Due to his astounding victory over the Turks in 619, Bagratuni was given a special robe decorated with gems, and the command of a number of the king’s royal guards. As a special honor, Khosrow II raised Bagratuni to third in rank among the nobles of the court. Armenians also supplied valuable light cavalry and excellent infantry, who were especially proficient in using slings to repel enemy cavalry, as well as spears for hand-to-hand combat.

Lightly armed cavalry were highly proficient with the bow; however, many foreign contingents would fight with other weapons such as javelins. Light cavalrymen were recruited from Iranian-speaking peoples such as the Alans of Arran/Albania (modern-day Republic of Azerbaijan), Gelanis of northern Persia, Kushans of Central Asia, and the Saka settlers of Afghanistan and eastern Iran. Many non-Iranian contingents such as Chionites, Hephthalites, and Turkic Khazars were also recruited. Like the Lakhmid Arabs (see below), an important function of warlike allied troops on the frontiers was to keep an invasion force in check until the arrival of the main Savaran forces.

Arab units were primarily efficient in desert warfare and proved invaluable in guarding the empire’s southern borders against marauding fellow Arabs in search of plunder. They were also very adept at scouting and raiding and proved invaluable to Shapur II during Julian’s failed campaign of 362.

Silver Drachm of Bahram II with Queen Shapurdukhtat and one of the crown princes. (Copyright British Museum)

The Sassanians sent Savaran units to bolster various Arabian allies in the Arabian peninsula such as Oman. The most effective and famous of these allies were the Lakhmids, who became the Sassanians’ chief Arab ally from the 4th century AD. They were equipped and fought like the Savaran, guarding the southern frontier against Arab tribes. They proved their worth as excellent warriors and supported the Savaran well, as at Callinicum (see page 50). Perhaps one of the empire’s greatest blunders was the dismantling of the Lakhmid kingdom by Khosrow II. The absence of these allies was a major military factor in facilitating the subsequent conquest of Persia by the Arabs from 637.

The role of camel-borne troops among the Sassanians is unclear, however Roman accounts do report them among the Parthians (see Herodian 4.28, 30). Camels stood higher than horses, which gave a significant advantage in archery. Although not as “glamorous” as the horse, the camel is more robust, resilient, and able to transport tremendous weight. The most famous depiction of a Sassanian warrior on a camel is that of the legendary Bahram Gur shooting arrows while accompanied by the petite figure of a female Byzantine companion (see page 15).