(RE-)RACIALIZING “THE CHARGE OF THE LIGHT BRIGADE”

In a 1990 episode of the television sitcom The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air wittily titled “Def Poets’ Society,” Will Smith joins the school poetry club. Commending this newfound interest in poetry (which of course is really an interest in girls), Geoffrey, the family’s excruciatingly proper Afro-British butler, informs Will that he too loves poetry, and in fact received first prize at the All-Devonshire Poetry Recital of 1963. Reliving his triumph, he begins to recite:

Cannon to the right of them,

Cannon to the left of them,

Cannon in front of them

Volleyed and thundered.

The choice of “The Charge of the Light Brigade” by the makers of The Fresh Prince accurately reflects its status as an enduring favorite for the study of elocution.1 What I want to call attention to is the role the poem takes on here as a marker, even (given its presumptive recognizability) an icon, of squareness—which is to say, of whiteness. This identification is reinforced later in the episode, when, for reasons that need not concern us, Geoffrey gets disguised in Afro and dashiki as “street poet” Raphael de la Ghetto. After reciting a poem that begins “Listen to the street beat” and ends “Listen, or I’ll kill ya!” he responds to the cries of “Encore!” by launching into “The Charge of the Light Brigade,” thereby blowing his cover and quickly losing the formerly rapt audience. The episode ends soon thereafter with Will’s aunt reciting a poem by Amiri Baraka. Canon to the right of them, canon to the left of them, indeed.

“The Charge of the Light Brigade” is a good choice to play the role it plays in The Fresh Prince because its subject matter—a disastrous advance by British cavalry in the Crimean War—and perhaps, more subtly, its cadence (which contrasts with that of Will Smith’s rapping, with which the episode opens) make the poem seem ludicrously removed from the experiences, interests, and expressive traditions of African Americans. What makes “The Light Brigade” an inspired choice, however, is not the self-evidence of this contrast but its history and historicity: there exists, in other words, a history of placing Tennyson’s poem in relation to African American culture, and this history is one in which this relationship has been variously construed and vigorously contested. As I will show, from the moment it was published, “The Charge of the Light Brigade” was mobilized, especially though not exclusively by African Americans, as a site or tool to address the kinds of issues adumbrated by The Fresh Prince: the relationship of African Americans to the dominant cultural tradition; the nature and politics of interracial cultural rivalry, mimicry, and appropriation; and the role of poetry and the arts—and violence (“I’ll kill ya!”)—in the fight for racial empowerment and equality.

The unlikeliness of “The Charge of the Light Brigade” filling this role reflects not only the poem’s subject matter but also its subsequent reputation as, in Jerome McGann’s words, “Tennyson at his most ‘official’ and most ‘Victorian’—a period piece.”2 While the historicist turn in literary criticism that McGann’s 1982 treatment of “The Light Brigade” advocated and exemplifies transformed the poem’s marked historical embeddedness into a source of value and interest (rather than contempt), this shift nevertheless has left intact an understanding of Tennyson’s poem as inextricably linked to the time and place of its composition and initial publication; thus, much recent scholarship on the poem focuses on specifying how the poem derives from and participates in the discourse attending the Crimean War.3 Yet the poem’s history is one of unusually widespread circulation and promiscuous susceptibility to adaptation and appropriation. (Paradoxically, even the poem’s felt obsolescence has contributed to its enduring cultural presence: think of the aging Victorian patriarch Mr. Ramsay in To the Lighthouse, with his self-dramatizing, self-pitying habit of reciting the poem to himself—not to mention The Fresh Prince.) Despite the insights they generate, then, efforts to locate Tennyson’s poem in its original historical context run the risk of construing that context too narrowly and freezing in one particular time and place a poem remarkable precisely for its broad appeal, longevity, and adaptability. This is a danger, I would suggest, to which the dominant recent modes of historicist work are especially prone, precisely because of their commitment to reconstructing the discursive context out of which a particular text emerges.

Consider the criticism McGann himself makes of Henry David Thoreau in his groundbreaking “Light Brigade” essay: quoting Thoreau’s comment that the charge of the Light Brigade proves “what a perfect machine the soldier is,” McGann says that “Thoreau’s view of the poem and its recorded events is based upon a gross misreading not only of the objective facts of the situation, but of the British response to those events,” a misreading McGann links to Thoreau’s “alien American vantage.”4 As we shall see, the nature and extent of this vantage’s alienness is and was debatable; indeed, Paul Giles has shown how Thoreau works to establish the distinctiveness and autonomy of American identity in the very text McGann cites.5 With regard to “The Light Brigade” in particular, McGann’s curious decontextualization of Thoreau’s remarks (curious because it comes in the midst of an argument for historical contextualization) misrepresents Thoreau’s intention and neglects or even, in its dismissiveness, obscures the real interest of his statement. Here is the complete sentence from Thoreau’s text, an 1859 speech titled “A Plea for Captain John Brown”:

The momentary charge at Balaclava, in obedience to a blundering command, proving what a perfect machine the soldier is, has, properly enough, been celebrated by a poet laureate; but the steady, and for the most part successful, charge of this man [John Brown], for some years, against the legions of Slavery, in obedience to an infinitely higher command, is as much more memorable than that, as an intelligent and conscientious man is superior to a machine.6

McGann’s criticism seems misguided insofar as Thoreau is clearly not trying to explicate the poem but rather to put it to use, rhetorically. Such a use is worth exploring on its own terms. This is especially so in this case because, as I will show, Thoreau is participating in a tradition that begins before and extends after him: that is, a tradition of deploying “The Charge of the Light Brigade” to think about antislavery violence. The recovery of this tradition promises to produce a more capacious understanding of the cultural work Tennyson’s warhorse of a poem has been called upon to perform.

Attention to this tradition can also alter our view of the poem itself. The example of Thoreau is again to the point: Thoreau’s ostensible “misreading” of the poem, if it is a misreading at all, is not “gross” but strong: after all, one meaning of “machine” is “a person who acts mechanically or unthinkingly, as from habit or obedience” (“Machine,” OED, def. 8b.), and the nobility of Tennyson’s soldiers lies precisely, notoriously, in their willingness to obey an order without “reason[ing] why.” Conversely, Thoreau’s belittling description of the Light Brigade’s charge as “momentary,” in contrast to John Brown’s “steady” effort, blatantly disregards the work the poem does to impart just such a sense of steadiness and prolongation to the Light Brigade’s action (especially through the use of repetition, as in the opening lines “Half a league, half a league, / Half a league onward”); yet by the same token, Thoreau’s drawing of this contrast calls attention to this aspect of the poem and suggests its stakes.7 Thus, insofar as Thoreau’s “vantage” differs from that of Tennyson’s English readers, this difference works to our advantage as well as his, as it produces insight into the nature and limitations of what Tennyson values about the charge of the Light Brigade. We will remain alert to the opportunity to garner similar insights from other contributions to the tradition at hand—a tradition, as we shall see, that itself quickly engages the very question of the value of such insights in the cause or in the face of matters of great political urgency.

RELOCATING TENNYSON

“The Charge of the Light Brigade” was first published in the London Examiner on December 9, 1854, five weeks after the event it describes. Among the many publications that quickly reprinted the poem was Frederick Douglass’ Paper, which ran the poem on January 12, 1855. As we saw in chapter 1, Douglass’ Paper—the most prominent antebellum publication owned and edited by an African American—routinely reprinted new British literature, running it alongside cultural reporting and original work by African American and white American authors as well as miscellaneous items from Dickens’s Household Words and other British periodicals. We have also seen that, while the American poetry and prose tended to be explicitly political or reformist, and often came from authors closely associated with the antislavery movement, the selections from British writers were more eclectic, with authors’ prominence rather than their declared or perceived political commitments often decisive.

The reprinting of a widely circulated poem by Britain’s poet laureate—prestigious, popular, and not known as a political activist—would seem to fit this model, but in fact this is not simply a case of the anglophile Douglass and his English literary editor, Julia Griffiths, showing their fealty to the canon in front of them. The Tennyson that emerges over the years in Frederick Douglass’ Paper has—or is ascribed—a politics, and a congenial one at that. The paper first published his work in 1851, soon after it began publication, reprinting the “Ring out, wild bells” section of the previous year’s In Memoriam. This selection’s call to “Ring in redress to all mankind” holds clear appeal for a reform-minded newspaper—and indeed, the reprinting of the poem in the context provided by Douglass’ Paper has the effect of giving specific content to the poem’s vague utopianism. Two years later, this implicit enlistment of Tennyson in the paper’s cause received confirmation of a sort when it was reported that Tennyson’s wife was among the thousands of signatories of an abolitionist petition from “the ladies of England”; a brief item in the paper wonders whether this will lead some supporters of slavery to refuse to read the poet’s work.8

Viewed, then, in the context of these other appearances by Tennyson and Douglass’ Paper’s literary offerings more generally, the appearance of “The Charge of the Light Brigade” is nothing out of the ordinary. Framed differently, however, “The Light Brigade” does stand out, not as an enigma but just the opposite, as one of the most transparently motivated British works to appear in Frederick Douglass’ Paper. For “The Charge of the Light Brigade at Balaklava”—to give the poem its full title as printed in Douglass’ Paper—was one item among many the paper published about the Crimean War. This coverage treats the war as a world-historical event and, more specifically, one front among several (including of course the antislavery movement itself) in the international battle for human rights and democracy. For example, one article celebrates the fall of Sebastopol to British and French troops as a victory over “the great Autocrat of Europe” and declares that “the hypocritical sympathies of American Republicanism in [Russia’s] behalf, will do her no good whatever.”9 Another piece published the same day goes even further in forging this connection: calling for a “convention of ideas,” the paper’s New York correspondent writes, “Old Thomas Aquinas held such a meeting when he discovered that ‘all men are born equal.’ . . . I rather think the general or public meeting which Aquinas inaugurated, and at which Jefferson reported his celebrated ‘Declaration,’ is not yet adjourned: committees are out, which are yet to report, some at Sebastopol, some in Kansas.”10 If “The Charge of the Light Brigade” is relevant to an antislavery readership, then, it is not because the poem transcends its occasion, but rather because its occasion, properly understood, transcends the particular time and place of its setting. This relevance was sufficiently evident that another leading abolitionist journal, the New York–based National Anti-Slavery Standard, also reprinted the poem, one day after Douglass’ Paper.

While the appearance of “The Charge of the Light Brigade” in Frederick Douglass’ Paper may have been unremarkable, the poem itself did not go unremarked. In contrast to most of the poems and stories published in Douglass’ Paper, which inspired no further comment,11 “The Light Brigade” immediately became part of the discourse of the paper, serving as a resource in the ongoing dialogue among its African American contributors. The first, most sustained, and most provocative of these rhetorical mobilizations of “The Light Brigade” appeared in the same issue as the poem itself. In fact, it appeared on the page preceding that on which “The Light Brigade” was printed, the recto to the poem’s verso. As we shall see, this upsetting of priorities proves entirely apt.

This piece, headlined “From Our New York Correspondent” and bearing the specification “For Frederick Douglass’ Paper,” is by James McCune Smith, the same writer who later aligns Sebastopol with Kansas. A regular contributor to Douglass’ Paper under the pseudonym “Communipaw,” Smith was the first African American to earn a medical degree (from the University of Glasgow) and has been called “the foremost black intellectual in nineteenth-century America.”12 His column’s treatment of the “Light Brigade” takes the form of a dialogue with “Fylbel,” a version of Smith’s friend Philip A. Bell, himself a leading African American editor and activist and regular contributor to Douglass’ Paper. Fylbel begins by asking Communipaw his opinion of the first two lines of Tennyson’s new poem, which he quotes approvingly. Communipaw responds with an appreciative formal analysis that takes the Western literary tradition as its frame of reference: Tennyson’s opening, he declares, “beats Virgil’s ‘quatit ungula campum;’ for we have not only the sound of the horses’ feet, as they begin with a canter, but the rush into the gallop. . . .”13 However, when Fylbel next quotes the same four lines we saw Geoffrey the butler recite in The Fresh Prince (“Cannon to the right of them,” etc.), Communipaw abruptly withdraws his approval of the poem with the startling accusation, “Flat burglary! . . . Tennyson has stolen the sweep’s blanket.” He then goes on to advance an understanding of the poem diametrically opposed to that evoked by The Fresh Prince, where, as we saw, the poem’s metrical form, historical referent, Englishness, and history as a recitation piece combined to signify whiteness. Here, by contrast, Smith declares that these lines are “a translation from the Congo, feebler than the original.”

Elaborating on this surprising claim, Smith juxtaposes Tennyson’s lines with a Congo chant “as old as—Africa”: “Canga bafio te, / Canga moune de le, / Canga do ki la, / Canga li.” Communipaw does not know the meaning of the chant’s words; what he is arguing, rather, is that Tennyson has “stolen” the chant as a formal construct—the anaphora, the stressed first syllable “can,” the short line-length, and, roughly, the meter. This form itself, moreover, seems to have a content, and one that the chant more or less shares with Tennyson’s poem as, before learning anything else about it, Fylbel responds “Hurrah for our mother-land! ‘Canga li!’ Glorious war cry; it beats ‘Volleyed and thundered,’ out of sight.” Fylbel’s identification of the poem’s function proves correct, as Communipaw goes on to explain that the chant was used to call slaves to rebel in Saint Domingo. Having first been transported beyond the site of its origination by enslaved Africans brought to the New World, the chant achieved wider dissemination via the circuits of cosmopolitan print culture, making it possible for Tennyson to have learned about it the same way Smith did: by reading about it in a French periodical. Smith even provides the citation (“Look in the Revue des Deux Mondes, Vol. 4th, page 1040”).14

The relative “feeble[ness]” of Tennyson’s poem, it turns out, is implicitly performative as well as aesthetic. Quoting (and translating) his source, Smith explains that the chant helped transform “indifferent and heedless slaves into furious masses, and hurled them into those incredible combats in which stupid courage balked all tactics, and naked flesh struggled against steel.” Thus, whereas Tennyson’s poem commemorates an advance against superior forces, the chant inspires such an advance—which, unlike the Light Brigade’s, is ultimately successful. Thrilled by what he learns from Communipaw—and as if intent on matching or exceeding the outrageousness of Communipaw’s accusation against Tennyson—Fylbel envisions using the Congo chant to reproduce the Haitian Revolution in the United States. Suggesting that “‘Canga li’ must yet ring in the interior of Africa,” he proposes renewing the African slave-trade to import a million Africans a year for six years: “then, in six years,” he reasons, “away down in the sunny South, these six millions of ‘children of the sun,’ restless under the lash, and uncontaminated, unenfeebled by American Christianity, may hear in their midst ‘Canga li,’ and the affrighted slave owners . . . will rush away North faster than they did from St Domingo.”15

In Smith’s column, then, Tennyson’s account of the heroic but doomed actions of British soldiers both derives from and gives rise to visions of equally heroic—but not always doomed—slave rebellions. While this account of the origins of Tennyson’s poem is unique to Smith, the rest of the pattern he establishes proves remarkably enduring. We will track it over the course of the century, but to see it a second time one need only turn the page of Douglass’ Paper: there, “The Charge of the Light Brigade” itself appears, followed immediately by another poem, “Loguen’s Position,” by E. P. Rogers. In this dramatic monologue, written by one African American minister and activist in the voice of another, the speaker describes himself as a fugitive who will not allow himself to be “drag[ged] back / To servitude again”:

I would not turn upon my heel,

To flee my master’s power;

But if he come within my grasp,

He falls the self same hour.

The speaker acknowledges that he “may be wrong” to reject “godlike” forgiveness, but he rejects it nonetheless—“But, were your soul in my soul’s stead, / You’d doubtless, feel as strong”—even as he ends with an appeal for God’s help:

Hasten, oh God! The joyful day,

When Slavery shall not be

When millions, now confined in chains,

Shall sound a jubilee.

The layout of this column of Douglass’ Paper thus recapitulates the discursive movement of Smith’s article from Tennyson’s poem to an embrace of violent resistance to slavery and anticipation of slavery’s end. It is as if the speaker of Rogers’s poem, like the reader of Douglass’s Paper, has just read “The Charge of the Light Brigade,” and done so through the lens Smith provides.

At the same time, the fact that the closing prayer in “Loguen’s Position” finesses the link between the speaker’s violence and the desired jubilee underscores how radical, if fantastic, Fylbel’s vision is. Communipaw himself retreats from Fylbel’s revolutionary plan, telling him not to raise his voice and changing the subject (even as Smith, of course, puts the plan in print). However, Communipaw (and Smith) are not done with Tennyson’s poem. Having viewed the poem through the lens of the antislavery struggle, Smith nimbly reverses course and uses the poem itself as a lens through which to view that struggle: claiming that Oliver Johnson, editor of the rival National Anti-Slavery Standard (which, as noted above, also published “The Charge of the Light Brigade”), “said ‘some one [i.e., Communipaw] had blundered,’” Smith responds by offering what may be the first in the long history of “Light Brigade” parodies and pastiches, one that capitalizes on the serendipitously trochaic names of his putative opponents within the abolitionist movement: “Wilson to right of them, / Chapman to left of them, / Johnson in front of them, / Volleyed and thundered.”16 Communipaw and Fylbel spin out this allegorical reworking (“You don’t mean to say Johnson cussed in volleys, do you?”), and the conversation ends with Fylbel asking “what, connected with your light Brigade, fits in with ‘all the world wondered,’” to which Communipaw replies, “Why, all the world wondered to see in the columns of the National Anti-Slavery Standard a light brigade of readable matter, not scissored from the New York Tribune, nor transcribed from Mother Goose’s melodies, nor Sinbad the Sailor.” In this final rhetorical maneuver, Smith’s extravagantly arbitrary metaphorization of “light brigade” repeats in miniature his radical recontextualization of “The Light Brigade” as a whole. These creative appropriations contrast sharply with the mechanical practices of “scissor[ing] and “transcrib[ing]”—practices that recall in turn the thievery of the poet laureate himself, who has “stolen the sweep’s blanket.”

Faced with this rhetorically slippery, tonally ambiguous treatment of “The Charge of the Light Brigade,” one is tempted to paraphrase General Bosquet’s famous remark about the charge itself: c’est magnifique, mais ce n’est pas le poème. James McCune Smith might easily concede this point, while denying its significance: like Thoreau a few years later, he clearly seeks to make use of “The Charge of the Light Brigade” for his own purposes. I will argue below that Smith’s treatment of “The Light Brigade” does in fact reveal more about the poem than simply its ready availability for appropriation. First, though, we should ask: if Smith is using “The Light Brigade” for his own purposes, what are those purposes? What does he hope to accomplish through his deployment of “The Charge of the Light Brigade”?

Accusations of plagiarism were common in mid-nineteenth-century American print culture.17 Then as now, such claims served as sources of rhetorical and cultural authority. Indeed, Smith returns to the matter of plagiarism after he leaves “The Light Brigade” behind, this time claiming that a recent column in Douglass’ Paper, by the regular contributor William Wilson (who published under the name “Ethiop”), contained two stolen passages: “the description of the Irish is vivid, only needing quotation marks and a reference to Frederick Douglass’ Address at Western Reserve College, from which it is copied with considerable accuracy”; “I don’t know that he has read Miss Brontë’s Villete [sic], else I would say that Dr. John [from that novel] and Mr. Meagher [from Wilson’s piece] had been drawn at the same sitting.” Smith does not bother to flesh out these accusations (there are no quotations, from either Wilson or his supposed sources), as if to underscore the authority that accrues from the very act of making them, or the role of his own authoritativeness in giving the charges weight.18

Smith’s claims themselves may seem strained or hyperbolic, but they are not outrageous by the standards of the day, for example in comparison to the best-known such charge, Poe’s attacks on Longfellow.19 As Pierre Bourdieu might put it, Smith is playing the game of literary and cultural criticism according to its prevailing rules. And playing it gleefully, as is made plain by yet another accusation of plagiarism by Smith in an earlier column; describing his discovery of the historian George Bancroft’s supposed borrowings from William Whewell’s The Plurality of Worlds, Smith writes, “Before I had finished the fourth paragraph, I clapped my hands and shouted, as Byron did, when he detected in Ivanhoe fourteen gems culled from Shakespeare within a few pages.”20

Like Poe, though, Smith displays his true mastery by not only playing the game but playing with the game, pushing its rules to their limits. In particular, he pushes the question of relative originality and derivativeness to the extremes of an originality so absolute as to seem originless (“old as Africa”), on the one hand, and an indebtedness that is sheer repetition (“flat burglary”), on the other.21 At the same time (to slide from one Bourdieuian metaphor to another), Smith expands the boundaries of the playing field, in two ways: first, by virtue of his own participation as an African American, and second, in his treatment of plagiarism as not only what we might call white-on-white (Bancroft/Whewell) and black-on-white (Wilson/Brontë), but also black-on-black (Wilson/Douglass) and, crucially, white-on-black (Tennyson/Congo). Given prevailing beliefs in the fundamental imitativeness of members of the African race and the absence of cultural or aesthetic value in their artifacts and activities, the notion of influence and indebtedness running in this direction is almost unthinkable at the time.

Such a notion is perhaps rendered less unthinkable by the contemporary popularity of blackface minstrelsy, a genre of performance Eric Lott has identified as “the first formal public acknowledgment by whites of black culture.”22 Yet it is one thing to ask “Why may not the banjoism of a Congo, an Ethiopian or a George Christy [a famous blackface performer], aspire to an equality with the musical and poetical delineators of all nationalities?,” as a writer in another antislavery journal asks a few months after Smith’s column, and another to argue that such equality or even superiority has been achieved; one thing to accuse “the filthy scum of white society” of “hav[ing] stolen from us a complexion denied to them by nature, in which to make money, and pander to the corrupt taste of their white fellow citizens,” as Frederick Douglass wrote of blackface performers in his newspaper in 1848, and another to lodge an accusation of theft against the most prestigious living practitioner of what was arguably the society’s most prestigious cultural form.23 Smith’s claim of African influence on high Western culture is quite possibly unprecedented, and even if his specific accusation proves unpersuasive, it introduces the profoundly subversive possibility of such influence. What matters most about the scenario Smith describes, then, is less its truth-content than its very expression, its being put into discourse. For Smith, no less than Tennyson, a (seemingly) wild charge can fail on one level and still succeed on another.

Similar considerations underwrite Smith’s deployment of “The Light Brigade” in his quarrel with the National Anti-Slavery Standard. As we saw, Smith claims that the editor of that paper had used the phrase “some one had blundered” in reference to Smith. In fact, the Standard had not quoted Tennyson’s poem, but it had called Smith “a mendacious blunderer.”24 The timing of this name-calling, only two weeks after the London publication of the poem and three weeks before its reprinting in both Douglass’ Paper and the National Anti-Slavery Standard, makes it unlikely that an allusion to Tennyson was intended. However, by retroactively turning the line into an allusion Smith again conjures a vision of an interracial, cosmopolitan discursive field, just as he did when tracing Tennyson’s poem back to Africa via Haitian revolutionaries and French reporting. Moreover, this swerve in the deployment of Tennyson’s poem from violent revolution to literary rivalry is not as great as it seems, for the column in question had claimed that the Anti-Slavery Standard did not adequately support the antislavery efforts of African Americans. As with Tennyson’s plagiarism and the Haitian Revolution, then, at issue here is the proper crediting of Africans and African Americans, and the crediting of them in particular with agency in fighting for their own freedom and equality. This emancipation and equality are intellectual as well as political and are what Smith’s bravura performance is designed to demonstrate as well as what it demands.

Smith’s agenda becomes more explicit in a companion piece published two months later. This essay, centering on a performance by the African American singer Elizabeth Greenfield, the so-called “Black Swan,” argues for the crucial role of the artistic achievements of “negros” in cultivating racial pride and combating discrimination. Gazing at Greenfield’s integrated audience, Smith asserts that “True Art is a leveler.”25 Crucially, however (and I will return to this point), this interracial leveling works not by leaving race behind but rather through its affirmation: thus, Smith particularly admires Greenfield for refusing to bend “to the requirements of American Prejudice” by “shrinking . . . under the cover of an Indian or a Moorish descent,” but instead “stand[ing] forth simple and pure a black woman.” “There is one thing our people must learn, and the victory is won,” Smith declares. “We must learn to love, respect and glory in our negro nature!”26

This column does not mention Tennyson explicitly, but the reader schooled in Smith’s own hermeneutic techniques has no trouble detecting his reworking of elements from “The Light Brigade”: while Tennyson enjoins us to “Honor the Light Brigade, / Noble six hundred!” Smith describes a company of the same size, similarly surrounded and outnumbered, witnessing if not performing a spectacular display of nobility: Greenfield’s concert, he reports, was attended by “upwards of two thousand persons . . . of whom at least six hundred were colored!” including fellow Douglass’ Paper correspondents Cosmopolite, Ethiop, and Observer, each of whom “had the luck to sit like thorns between blushing roses” while the Black Swan demonstrated “the nobleness of her nature.”27 Again, then, “The Light Brigade” is radically reimagined in such a way as to address race relations and celebrate black achievements.

No one ever seems to have taken up Smith’s accusation of Tennyson. The poet himself, I will argue below, was uniquely well positioned to recognize its uncanny power, but he was presumably unaware of Smith’s column.28 However, other aspects of Smith’s treatment of “The Light Brigade” did not go unnoticed—or unchallenged—in the pages of Frederick Douglass’ Paper itself. The use of Tennyson’s poem to envision an antislavery insurrection prompted one forceful response, as did its use to theorize the relationship between race and culture. Both of these responses, printed back-to-back in the April 20, 1855, issue of Douglass’ Paper, rejected the positions Smith used “The Light Brigade” to advance, and used the poem instead to envision a postracist and indeed postracial world.

In the first piece, a letter, the antislavery activist Uriah Boston advocates a policy of “lessen[ing] the distinction between the whites and colored citizens of the United States” by having “colored people” renounce their identity as Africans to claim full and sole American citizenship. He distinguishes his position from one he attributes to Smith and William Wilson (Ethiop), who, he says, “would not have the colored people imitate nor mix with the whites” but instead “would have . . . three millions of Africans contending with 24 millions of Americans . . . for the rights of American citizens.” Such a contest, writes Boston, “would be more fatal to the colored race than the brave and daring charge of the British Light Brigade at Balaklava. Nay,” he continues, “the foolish daring of the British Light Brigade would be justly considered an act of wisdom, compared with the conduct of 3 millions Africans charging 24 millions Americans on the ground selected by the Americans themselves. One such charge would result in the annihilation of the African Brigade, with no prospect of recruits.” Boston thus rejects both Smith’s oft-articulated stance of racial exceptionalism and the specific, “Light Brigade”–inspired (or ur–“Light Brigade”–inspired) advocacy of insurrection voiced by “Fylbel,” finding these positions less subversive than suicidal.29

“Fylbel” himself—Philip Bell—gets his say in a column immediately following Boston’s letter. Writing under his regular pseudonym, “Cosmopolite,” Bell leaves aside talk of violence to focus more squarely on Tennyson’s poem, which he compares favorably to “Balaklava,” another Crimean War poem reprinted in Douglass’ Paper. Bell praises Tennyson’s “thrilling lyric” for its vividness: “we can almost hear the stern command, ‘Forward the Light Brigade!’ and the tramping of the steeds, as ‘Into the valley of Death / Rode the Six Hundred!’”30 The “short, terse, and epigrammatic repetition” of “Half a league, / Half a league, / Half a league onward,” he asserts, is “unsurpassed in the language, and only equaled by Coleridge’s ‘Alone! Alone! All, all alone! / Alone on the wide, wide sea!’”

Bell thus returns here to the kind of apolitical, appreciative formal analysis we saw Smith engage in before his ostensible discovery of plagiarism. Yet Bell’s column as a whole makes it clear that this lack of engagement with race is pointed—and pointed directly at Smith. Bell begins by taking issue with Smith’s comments on the “Black Swan”: “True Art,” he declares, “is an elevator, not a leveler, as an old low Dutch writer once remarked.” The distinction between leveling and elevating may seem a fine one, but it indicates very different political visions. For Bell as for Smith, art defeats prejudice, but for the former the equality it establishes is less one of mutual respect between races, as for Smith, than one where race is transcended altogether: according to Bell, art “elevates the mind above the petty prejudices of caste and color.” Bell develops this position by recounting his visit to an art gallery, where he sees a wealthy, refined white woman turn to the African American woman next to her and say of the painting before them, “How beautiful!” Bell interprets this moment as showing that for this white woman, “the ennobling influence of Art elevates the hitherto despised being at her side to her own standing.” Elaborating, he asserts that “in the presence of that inimitable and inspired work of art, no prejudice can enter. Caste is forgotten, and colorphobia is rebuked into silence.” He then goes on to analyze Tennyson’s poem. Thus, although Bell does not make explicit the relationship between his column’s parts, his discussion of “The Charge of the Light Brigade” serves to enact this ideal silence and forgetting.31

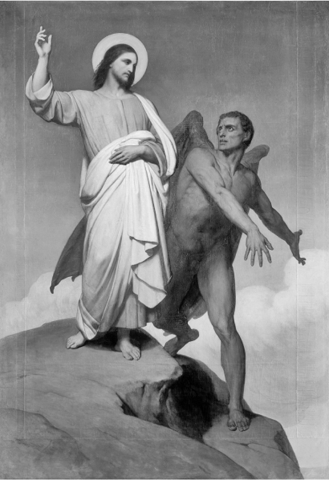

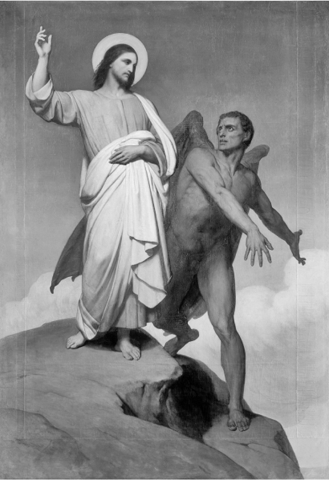

Yet Bell’s deracialization of art turns out to be just as willful as was Smith’s racialization. For the painting with which Bell chooses to make his case is almost perfectly unsuited to the task: while Ary Scheffer’s Temptation of Christ contrasts “the sublime features and angelic countenance of Christ” with “the fiendish expression of the Tempter,” as Bell says, it does so by invoking the very codes he sees art negating: Christ’s skin tone is much lighter than Satan’s, and Christ is standing on a mountaintop slightly higher than Satan.32 (See figure 2.1)

The painting thus depicts and celebrates the scenario Bell describes it as repairing: a light-toned figure elevated above one of “darker hue” at its side. One might view this irony as testimony to the utopian potential of aesthetic experience, whereby even racist art can have an antiracist impact—that is, whereby even art that encodes racist beliefs can produce an aesthetic experience that does not reinforce but instead transcends those beliefs. However, Bell’s failure to spell out this argument himself raises the possibility that his devotion to Western art has blinded him to its racism.

Bell’s problematic appreciation of Scheffer’s painting casts a shadow over his subsequent appreciation of “The Light Brigade.” If, in attempting to demonstrate the silencing of “colorphobia” Bell instead overlooks the presence and persistence of that colorphobia, then the forgetting of race enacted by his discussion of “The Light Brigade” risks seeming naïve, ineffectual, or even inadvertently complicit with the racism it seeks to combat. Recognition of the painting’s racialized visual vocabulary also raises the question of whether a similarly racialized rhetoric is at work in Tennyson’s poem. For example, does the poem pun on “light,” so as to suggest “not-dark” as well as its original meaning of “not-heavy”? Is Tennyson’s light brigade the light brigade not only because it is not the heavy brigade but also because it is not, in Uriah Boston’s phrase, “the African brigade”?

Philip Bell’s commitment to a color-blind, race-transcending cultural sphere keeps him from asking such questions, and the exchange in Douglass’ Paper concerning “The Charge of the Light Brigade” ends with his column. However, that exchange—and James McCune Smith’s column in particular—not only invites us to address such questions ourselves but also points the way toward answers. Rather than tacitly employing racialized imagery, I will argue, “The Charge of the Light Brigade” constitutes an active withdrawal or disengagement on Tennyson’s part from the racial rhetoric he employs elsewhere. The very topicality of this most topical of poems can be fruitfully understood as a deracializing recontextualization—can be fruitfully understood, that is, along lines first proposed by James McCune Smith.

2.1. Ary Scheffer, The Temptation of Christ, 1854. Oil on canvas, 136″ × 95″. Musée du Louvre, Paris. Photo: Hervé Lewandowski. © RMN–Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY.

TENNYSON RELOCATING

James McCune Smith’s initial insights into “The Charge of the Light Brigade”—his identification of Virgil as Tennyson’s key precursor and his reading of the rhythm and repetition of “The Light Brigade” as mimetically representing the cavalry’s advance—are now widely accepted. Indeed, even Smith’s version of the poem’s genesis bears a striking resemblance to the well-known version later related by Tennyson’s son Hallam, who similarly claimed that “the origin of the metre of [the] poem” came from a passage in a periodical—specifically, from the phrase “some one had blundered” in the Times.33 Only when Smith transforms the Crimea into a palimpsest of Haiti and Africa, then, does his acumen as a reader of Tennyson come into question—or start to seem beside the point.

In leaving behind emerging Tennysonian commonplaces, however, Smith does not leave behind common Tennysonian places. Instead, his revisionary framing of “The Light Brigade” takes the English poet to places his poetry had already visited and would return to again: earlier in his career Tennyson wrote a number of poems set in the tropics, including both Africa and Haiti, and he would write about Haiti again toward the end of his life (in “Columbus”). Of particular interest here is “Anacaona,” which Tennyson wrote sometime between 1828 and 1830 but refused to publish during his lifetime: drawing from the transatlantic circulation of accounts of transatlantic circulation to bring together Haiti, song, and the violent replacement of one racial regime by another, this poem bears an uncanny resemblance to “The Light Brigade”—according-to-Smith.

Basing his account on an American text—Washington Irving’s Life of Columbus34—Tennyson begins the poem by describing the edenic life of “The Indian queen, Anacaona” (28) in her “cedar-wooded paradise” (20):

A dark Indian maiden,

Warbling in the bloomed liana,

Stepping lightly flower-laden,

By the crimson-eyed anana,

Wantoning in orange groves

Naked, and dark-limbed, and gay,

Bathing in the slumbrous coves,

In the cocoa-shadowed coves,

Of sunbright Xaraguay,

Who was so happy as Anacaona,

The Beauty of Espagnola,

The golden flower of Hayti? (1–12)35

The arrival of “The white man’s white sail” (49) interrupts this idyll, although at first Anacaona, in her innocence, welcomes the “fair-faced and tall” Spaniards:

Naked, without fear, moving

To her Areyto’s mellow ditty,

Waving a palm branch, wondering, loving

Carolling “Happy, happy Hayti!”

She gave the white men welcome all,

With her damsels by the bay. (61–66)

As Irving recounts, despite this welcome the Spanish execute Anacaona and massacre her people. This fate is rendered elliptically in the poem, which ends:

But never more upon the shore

Dancing at the break of day,

In the deep wood no more,—

By the deep sea no more,—

No more in Xaraguay

Wandered happy Anacaona,

The beauty of Espagnola,

The golden flower of Hayti! (77–84)

In “Anacaona,” as in Smith’s ur-version of “The Light Brigade,” then, the dark-skinned people of Haiti use song as they attempt to negotiate their relationship to Europeans. The earlier poem depicts natives as victims, rather than slaves of African descent as revolutionaries, yet even so we are not as far off from Smith’s version as it might seem: as Marcus Wood points out, “Anacaona” not only draws from Irving but also “develops out of the tropes of abolition poetry dealing with the natives of Hispaniola”36; Wood goes so far as to include the poem in an anthology entitled The Poetry of Slavery. In Samuel Whitchurch’s 1804 poem Hispaniola, in particular, the voice of the murdered Anacaona (there spelled “Anacoana”) curses future generations of European conquerors and prophesies the Haitian Revolution itself:

“Then mourn not much-loved summer isle,

Again on thee shall freedom smile,

Though on thee prey the vultures of the north:

Brave sable nations shall arise,

And rout thy future enemies,

Though Europe send her hostile legions forth.”37

Here we come close to the past Communipaw describes and the future Fylbel envisions. Smith’s column thus rewrites “The Light Brigade” as “Anacaona” as “Hispaniola.”

The series of transformations here may seem dizzying, but the ironies are multiple and pointed. By reading Tennyson in the context of the Haitian Revolution, Smith undoes the work of “Anacaona” itself, for the Haitian Revolution is not simply absent from “Anacaona” but rather is absented from it, abjected. That is, “Anacaona” does not simply fail to invite thoughts of the Haitian Revolution but instead actively combats them—or more precisely, it invites readers to combat the very thoughts it invites. Tennyson gives his poem an actual historical setting (as opposed to his frequent preference, especially early in his career, for literary and mythical locales), and one with a well-known recent past that other poems have linked to the more distant past he evokes. The ghost of the Haitian Revolution thus threatens to haunt “Anacaona” just as the ghost of Whitchurch’s Anacoana haunts the Haitian Revolution. However, the ending of the poem attempts to lay this ghost by emphatically sealing off the represented historical moment: quoth the poet, “never more . . . no more . . . no more,— / No more.” The repetition here is as anxious as it is paradoxical, as if the poet does not so much lament the irrevocable silence of Haiti’s colored inhabitants as fear that it is not irrevocable, that these inhabitants may one day assert themselves violently and successfully. From this perspective, Smith’s claim that Tennyson has plagiarized a poem that does not merely represent but in fact incited the Haitian Revolution constitutes the return of the repressed with a vengeance, as the return of repressed vengeance.

One might object that Tennyson’s insistence on the irrevocable nature of Anacaona’s silencing can be attributed not to a fear of black agency but to a commitment to historical truth: after all, the natives of Haiti were in fact wiped out and are not interchangeable with the slaves of African descent who later populated the island. Yet anxiety over the agency of people of color is plainly visible, and this agency plainly rendered invisible, in the (non)publication history of the poem itself. As noted earlier, Tennyson refused to publish “Anacaona” during his lifetime. According to his son, the primary reason he gave for this refusal was the poem’s scientific inaccuracies: “My father liked this poem but did not publish it, because the natural history and the rhymes did not satisfy him. He evidently chose words which sounded well, and gave a tropical air to the whole, and he did not then care, as in his later poems, for absolute accuracy.”38 In the words of Edward FitzGerald’s similar report, Tennyson worried that the poem “would be confuted by some Midshipman who had been in Hayti latitudes and knew better about Tropical Vegetable and Animal.”39 Leaving aside for a moment the persuasiveness of this explanation, we can note that, on this account, the possibility of being confuted by someone who actually inhabits, rather than visits, “Hayti latitudes” does not seem to occur to Tennyson (or FitzGerald): again, here, the agency of people of color is absent. Yet the letter in which Tennyson in fact refuses to allow publication of the poem conjures a disturbing image of just such agency: referring to “that black b— Anacaona and her cocoa-shadowed coves of niggers,” the poet says, “I cannot have her strolling about the land in this way—it is neither good for her reputation nor mine.”40 Tennyson not only grants people of color dangerous agency here, but also does so in language that collapses any distinction between the island’s extinct original inhabitants and its present-day, recently self-empowered inhabitants. This letter thus affirms the transhistorical, interracial link Whitchurch elaborates and, I have argued, “Anacaona” forcibly forgets.

Viewed through the lens provided by James McCune Smith, then, Tennyson’s most widely circulated poem morphs into a version of a poem Tennyson refused to publish, albeit a version that highlights the very agency, and the very historical event, that the latter poem itself represses. Although Smith himself could not have been aware of this irony, it is very much in keeping with the spirit and tactics of his column, which ends by turning another poem by a prominent white poet into a celebration of black agency. Asserting the necessity of black solidarity to defeat slavery, Smith writes:

dark hands must be knit to dark hands, and the souls of blacks must be bent into one soul, to make the strong pull which shall

“shake the pillar of our common weal”

free from the Mammoth Evil.

Smith here cites Henry Wadsworth Longfellow to make vivid his own argument that the unified efforts of African Americans will bring an end to slavery. As its title indicates, however, Longfellow’s poem is a “Warning”: rather than calling on blacks to “shake the pillars of this Commonweal,” as Smith does, Longfellow warns that slavery must be abolished in order to prevent slaves from committing this Samson-like act, which he believes would leave “the vast Temple of our liberties / A shapeless mass of wreck and rubbish.” Smith’s rhetorical sleight of hand transforms this representation of black action as a threat to be avoided into a call for just such action.

Smith’s commentary on “The Light Brigade” also reinscribes another aspect of “Anacaona” that that poem’s suppression seems intended to suppress. Even as the earlier poem obscures the Haitians’ latter-day political agency, it highlights Anacaona’s artistic creativity as the composer and performer of “areytos,” which Washington Irving glosses as “the legendary ballads of her nation.”41 As A. Dwight Culler was perhaps the first to note, Anacaona thus serves “as a symbol of the poet”42; going further, James Eli Adams suggests that Tennyson’s disavowed identification with this Indian queen contributes to his “uneasy relation” to the poem and decision not to publish it.43 In Smith’s article, however, the kinship between Tennyson and a dark-skinned composer of legendary national ballads returns in nightmarishly exaggerated form: identification collapses into identity, as one of Tennyson’s own areyto-like compositions is “revealed” as a pilfered (Afro-)Haitian chant.44

Beyond these ramifying ironies, Smith’s reframing of “The Charge of the Light Brigade” sheds new light on the poem’s place in Tennyson’s oeuvre. If, as I have argued, Smith’s argument regarding the origins of “The Charge of the Light Brigade” unearths a buried dynamic in the buried “Anacaona,” in so doing it does not simply leave behind the original “Light Brigade”—that is, Tennyson’s—but instead invites us to read it in the company of “Anacaona” and those poems with which “Anacaona” is invariably grouped: Tennyson’s poems set in or fantasizing about exotic locales at or beyond the margins of the West, such as “Timbuctoo,” “The Hesperides,” “Locksley Hall,” and especially “The Lotos-Eaters,” which also draws from Irving’s Life of Columbus.45 Critics have read these poems as exhibiting, and to varying degrees policing, an eroticized resistance to the demands of Victorian masculine self-discipline and the perceived marginalization of the imagination in increasingly utilitarian England.46 By contrast, “The Charge of the Light Brigade” is typically read as a jingoistic celebration of just such self-discipline.47 When brought into contact with these other poems, however, suggestive similarities emerge, and the Crimea becomes visible as another such seductively exotic locale, Lotosland—or Haiti—by another name. Thanks to their self-discipline, for example, the soldiers in the Light Brigade achieve the death that Ulysses’ weary men, “stretched out beneath the pine” (144), so obviously crave in “The Lotos-Eaters,” even as Tennyson himself seeks to improve on the performance of the “minstrel” who sings of their “great deeds, as half-forgotten things” (123); indeed, this pairing brings out the anxiety lurking beneath the boastfulness of the seemingly rhetorical question posed in the final stanza of “The Light Brigade”: “When can their glory fade?” (50).

The pairing of “The Light Brigade” with “Anacaona” is perhaps even more suggestive. For all their differences, both poems commemorate the victims of massacres resulting from international contact, and both end with an exclamatory reference to the massacred. The image of the royal Anacaona leading the Spaniards “down the pleasant places” contrasts with the noble Light Brigade’s ride “Into the valley of death,” but the descents prove equally tragic. One key difference is that the soldiers, unlike Anacaona, know what to expect. “The Light Brigade” thus stands as the song of experience to the earlier song of innocence. Or perhaps vice versa, insofar as “Anacaona” mourns the tragic encounter of innocence with experience, while “The Light Brigade” celebrates the heroic achievement of willed innocence (“Their’s not to reason why”).

This convergence of the two poems is captured by one key word that links the Indian queen and the British cavalry: wild. Anacaona sings “her wild carol” (73) while the Light Brigade, of course, makes its “wild charge.” This echo calls attention to the curiousness of Tennyson’s word choice in the later poem: as critics have noted, there was nothing wild about the charge as described in the press accounts Tennyson would have seen (recall Thoreau’s word, “machine”).48 Indeed, to describe the Light Brigade’s actions with a word that carries among its primary meanings “not under, or not submitting to, control or restraint” and “rebellious”49 directly contradicts the burden of the poem. It does, however, suggest a point where the pure wildness of Anacaona’s song (its uncultured naturalness, its freedom from restraint) meets the wild (reckless, imprudent) purity of the Light Brigade’s discipline.50

These similarities between “Anacaona” and “The Charge of the Light Brigade” render one difference between the two poems particularly striking. Anacaona and her wild carol are repeatedly, insistently situated in and identified with a particular place, but the Light Brigade and its wild charge are not: almost every stanza of “Anacaona” mentions Xaraguay and every stanza ends by describing Anacaona as “The beauty of Espagnola, / The golden flower of Hayti,” whereas “The Charge of the Light Brigade” mentions neither a place name nor the nationality or race of the Light Brigade itself. One might argue that the circumstances of the latter poem’s production and initial publication rendered such specifications superfluous—one would hardly expect Tennyson to write of “the British Light Brigade,” as we saw Uriah Boston do—but the additional contrast between the earlier poem’s detailed attention to Haiti’s flora and fauna (however erroneous) and the later poem’s terse evocations of a diagrammatic, allegorized landscape (“right of them,” “left of them,” “in front of them,” “behind them”; “the valley of Death,” “the mouth of Hell”) underscores the centrality of this referential reticence to Tennyson’s aesthetic strategy.51 If, as I have argued, “The Light Brigade” constitutes a resituating on Tennyson’s part of interests and desires he had explored previously in poems set in the tropics, then it also constitutes a retreat from situatedness itself.

In a final irony, however, the race-neutralizing abstraction and allegory of “The Charge of the Light Brigade” heightens the poem’s availability for adaptation or particularization; in other words, Tennyson’s decontextualization paradoxically facilitates the poem’s recontextualization. It is ironic but not necessarily surprising, then, that even though James McCune Smith’s dialectical negation of the poem’s negations may be uncannily precise and revealing, his African Americanization of “The Light Brigade” is also only the first in a decades-long series that extends well beyond the initial responses he inspired in the pages of Frederick Douglass’ Paper. Despite and because of Tennyson’s best efforts, “The Charge of the Light Brigade” will be repeatedly deployed in contexts where race is explicitly at issue.

BLACK BRIGADES: THE CIVIL WAR “LIGHT BRIGADE”

This initial engagement with “The Charge of the Light Brigade” ends with Bell’s column. However, Tennyson’s poem will maintain a presence in the lives and writings of nineteenth-century African Americans. In the following decade and beyond, this presence will continue to raise questions—and “The Charge of the Light Brigade” will continue to be used to address questions—about the role of culture in reproducing and challenging racism, the costs and benefits of participation in the dominant culture, the universality and particularity of literature, and, in Uriah Boston’s stark terms, African American assimilation and annihilation.

One form taken by the African American engagement with Tennyson’s poem in the nineteenth century is the form it takes in The Fresh Prince: recitation, both in schools and public performances.52 Such recitation of “The Light Brigade” provides a means to lay claim to participation or membership in the dominant culture, like the performance by James McCune Smith’s Black Swan. Yet absent anything like Smith’s claim for an African role in the making of this poem, or this culture, on the one hand, and given what we have just seen of Philip Bell’s vexed color blindness, on the other, we might ask whether we should understand the teaching and performance of Tennyson’s poem as promoting an empowering cultural literacy, on the one hand, or a deracinating cultural mimicry, on the other—or, indeed, some combination of the two, with deracination the price of empowerment? For young African Americans in the 1860s, what is the Crimea to them, or they to the Crimea, that they should read and recite about it?

Eventually, the teaching of Tennyson’s poem will be criticized along these lines. In a 1922 essay advocating, as its title indicates, “Negro Literature for Negro Pupils,” “The Charge of the Light Brigade” is one of the few works Alice Dunbar-Nelson targets by name for replacement in the curriculum. Arguing for the need to “instill race pride into our pupils” by giving them “the poems and stories and folk lore and songs of their own people,” Dunbar-Nelson proposes substituting George Henry Boker’s 1863 poem “The Second Louisiana” (also known as “The Black Regiment”).53 While also by a white author, “The Second Louisiana” celebrates the pivotal role of an African American regiment in the Battle of Port Hudson, Louisiana. As in The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air, “The Charge of the Light Brigade” comes to represent that which must be cleared away to make room for black history, experience, and expression. In a similar spirit, at around the same time, when the pan-Africanist Marcus Garvey attempted to purchase a ship named the Tennyson for the Universal Negro Improvement Association’s Black Star Line, he announced his plan to rechristen it the Phyllis Wheatley.54

No hint of such criticism or such a binary opposition is present in the 1860s reports in the African American press on the recitation of Tennyson’s poem. What one finds in their place is not necessarily an indifference to the question of fit between text and student, nor an attempt to relocate both poem and reader to a realm of universality; instead, there are indications that Tennyson’s poem has been selected with an eye toward its timeliness and felt relevance for these students, as a poem about war.55 Thus, “The Light Brigade” is reported being read at one high school exam along with a poem called “Restoration of the Flag to Fort Sumter.”56 In direct contrast to Dunbar-Nelson, another article reporting on a reading by graduates of the Institute for Colored Youth does not oppose Tennyson and Boker but instead aligns them: the evening’s main performer, we learn, first came to prominence “as an orator . . . on the occasion of the organization of the Pennsylvania State Equal Rights League” two months earlier, “when he recited ‘Boker’s Black Regiment,’ in such an able and masterly style.”57

It is not surprising that Boker’s poem in particular gets paired with Tennyson’s, since this pairing begins in Boker’s poem itself: in celebrating the sacrifices of African American troops in the Civil War, “The Second Louisiana” takes “The Light Brigade” as its model. This African Americanization of Tennyson’s poem indicates both the poem’s continued resonance and its limitations. On the one hand, that is, the turn from “The Light Brigade” to “The Black Regiment” does not leave Tennyson’s poem behind but instead maintains and affirms its presence, as resource or influence. On the other hand, the existence of a “black” version of “The Light Brigade” turns “The Light Brigade” into a “white” version of itself—that is, into the racially marked poem Dunbar-Nelson will see, rather than the race-transcending one praised by Philip Bell.

Boker’s formal debt to Tennyson is evident, as his poem commemorates the martyrdom of a regiment in the distinctive dactylic dimeter of “The Light Brigade”:

Trampling with bloody heel

Over the crashing steel,

All their eyes forward bent,

Rushed the Black Regiment.58

Boker also borrows Tennyson’s use of anaphora:

“Freedom!” their battle-cry—

“Freedom! or leave to die!”

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Glad to strike one free blow,

Whether for weal or woe;

Glad to breathe one free breath,

Though on the lips of death.

Boker’s ending reworks Tennyson’s, replacing the imperative to “Honor the charge they made, / Honor the Light Brigade, / Noble six hundred” with a demand focusing on the survivors:

Oh, to the living few,

Soldiers, be just and true!

Hail them as comrades tried;

Fight with them side by side;

Never, in field or tent,

Scorn the Black Regiment.

Rather than the recitation of “The Charge of the Light Brigade” serving to demonstrate the humanity, equality, or artistry of African Americans, then, the poem gets adapted to describe—and increase—their own agency in securing that equality. Whereas Uriah Boston feared a suicidal charge resulting in “the annihilation of the African Brigade, with no prospect of recruits,” Boker celebrates a small-scale annihilation, and does so precisely to generate more recruits: “The Second Louisiana” was published by Philadelphia’s Supervisory Committee for Recruiting Colored Regiments.

When Dunbar-Nelson proposes that “Negro pupils” read “The Second Louisiana” instead of “The Light Brigade,” she suspends her essay’s emphasis on black authorship (even as she is careful to omit Boker’s name, in contrast to her practice of identifying the African American authors of the works she recommends).59 Yet “The Light Brigade” also gets deployed in poems by as well as about African Americans—on the very same subject as Boker’s.60 The first such poem is likely James Madison Bell’s monumental, 750-line “The Day and the War” (1864). Unlike Boker, Bell abandons the metrical form of “The Light Brigade” in favor of a more conventional iambic tetrameter, usually in rhymed couplets; also unlike Boker, however, Bell openly thematizes his relationship to Tennyson, acknowledging the English poet’s precedent while claiming an originality of his own:

Though Tennyson, the poet king,

Has sung of Balaklava’s charge,

Until his thund’ring cannons ring

From England’s center to her marge,

The pleasing duty still remains

To sing a people from their chains—

To sing what none have yet assay’d,

The wonders of the Black Brigade.61

Bell’s characterization of Tennyson as “the poet king” is less unequivocal as praise than it might seem, for earlier in the poem he criticizes Britain for supporting the South in the Civil War and states that “kindred spirits there are none, / Twixt a Republic and a throne.” This stance may have contributed to Bell’s decision to present himself and the African American soldiers at the battle of Milliken’s Bend as competing with Tennyson and the Light Brigade, rather than emulating them:

Let Balaklava’s cannons roar

And Tennyson his hosts parade,

But ne’er was seen and never more

The equals of the Black Brigade!62

Like James McCune Smith, Bell uses Tennyson’s poem as a foil to assert the primacy of black freedom fighters. Superiority over the Light Brigade takes the form of a more complete martyrdom:

out of one full corps of men,

But one remained unwounded, when

The dreadful fray had fully past—

All killed or wounded but the last!63

As opposed to “The Charge of the Light Brigade,” moreover, this martyrdom portends the eventual triumph of the cause: “The Day and the War” was written to celebrate the first anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation.

Although Bell’s insistence on the unequaled valor of the Black Brigade comes at the expense of the Light Brigade, he does not devalue the actions of the Light Brigade, or the poetry of Tennyson, as aggressively as we saw Thoreau do when celebrating John Brown and his men. Like Thoreau’s speech, however, “The Day and the War” also positions Brown and his men in relation to the Light Brigade. James Madison Bell was Brown’s friend and supporter, and “The Day and the War” is dedicated to “the hero, saint and martyr of Harper’s Ferry . . . by one who loved him in life, and in death would honor his memory.”64 In Bell’s poem, I would suggest, the Light Brigade ironically comes to serve as a kind of stand-in for or displaced version of Brown and his men. The Black Brigade’s comrades in arms, they are also their rivals in valor, an inspiring but humbling example of heroic resistance to slavery. The combination of the poem’s opening dedication to Brown and its closing near-apotheosis of Abraham Lincoln—the last two lines are “And tribes and people yet unborn, / Shall hail and bless his natal morn”65—underscores the burden the Black Brigade carries in the middle of the poem as its specifically African American (counter)example of heroic agency.

With their treatment of “The Light Brigade” as a resource with which to conjure images of African American freedom fighters, James Madison Bell and George Henry Boker take a stance closer to James McCune Smith’s revolutionary “Fylbel” than Philip Bell’s proto-Arnoldian “Cosmopolite.” By the time of the publication of “The Day and the War,” however, such images have migrated from the realm of militant prophecy to that of current events. This historical development helps explain an increased openness to such racializations of the poem on the part of Philip Bell himself: Bell contributed a summarizing “Introductory Note” to “The Day and the War.”66 Nonetheless, the war hardly settled the question of transracial elevation vs. interracial leveling, and Bell seems never to have abandoned his belief in the former: in an article a year later, even as he describes “The Light Brigade” being read at a fundraiser for San Francisco’s African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, Bell retains his earlier practice of strategic color blindness or silence, never identifying the performer by race. This article appears in a newspaper Bell himself had recently founded: the Elevator.67

FADED GLORY: THE WANING “LIGHT BRIGADE”

The end of the Civil War did not end the use of “The Light Brigade” pioneered by “The Black Regiment” and “The Day and the War.” However, the passage of time did change the poem’s resonance. We see this in Paul Laurence Dunbar’s 1895 poem “The Colored Soldiers,” which again makes use of “The Charge of the Light Brigade” to celebrate the role of African American troops in the Civil War.68 Dunbar’s soldiers, like Tennyson’s, valiantly storm “the very mouth of hell” (32), and the final stanza of “The Colored Soldiers” tracks that of “The Light Brigade”:

When can their glory fade?

O the wild charge they made!

All the world wondered.

Honour the charge they made!

Honour the Light Brigade,

Noble six hundred!

And their deeds shall find a record

In the registry of Fame;

For their blood has cleansed completely

Every blot of Slavery’s shame.

So all honor and all glory

To those noble sons of Ham—

The gallant colored soldiers

Who fought for Uncle Sam! (73–80)

The unmistakable echo of the “Light Brigade” here derives not simply from the shared vocabulary—“honor,” “glory,” “noble”—and assertions of immortality, which are arguably generic, but from these features in combination with the similar syntax of the poems’ final sentences, as Dunbar’s concluding exclamation bestows the honor Tennyson’s demands.

Crucially, however, unlike Tennyson’s poem—and Boker’s and Bell’s—Dunbar’s poem does not inhabit the moment it describes. Instead, “The Colored Soldiers” looks back three decades, and the poem takes as its topic the difference this temporal gap makes. As Jennifer Terry has noted, Dunbar is writing “against a backdrop of rising anti-black violence and the widespread collapse and reversal of political and legal gains made by African Americans during the post-war period.”69 He calls on an earlier heroic moment and poetic model to counteract this backsliding, which is directly addressed in the poem: “They were comrades then and brothers, / Are they more or less to-day?” (57–58), “And the traits that made them worthy,— / Ah! those virtues are not dead” (63–64). Tennyson’s poem not only models a call for permanence but, forty years after its publication, models that permanence itself.

Yet there are poignant ironies in Dunbar’s turn to “The Light Brigade,” deriving from both the specific content of Tennyson’s poem and its subsequent reputation. When Boker and James Madison Bell deploy Tennyson’s poem, they pick up the theme of martyrdom but leave behind the poem’s crucial attention to the fact that the charge it describes was also a mistake and a failure: a blunder. Dunbar similarly argues that the sacrifices he describes contributed to victory:

Yes, the Blacks enjoy their freedom,

And they won it dearly, too;

For the life blood of their thousands

Did the southern fields bedew.

In the darkness of their bondage,

In the depths of slavery’s night,

Their muskets flashed the dawning,

And they fought their way to light. (49–57)

The problem, however, is that Dunbar’s goal is precisely to counteract the possibility that this mission failed—that these flashing muskets are no less glorious but also no more successful than the Light Brigade’s flashing sabers. The turn to Tennyson thus implies exactly what “The Colored Soldiers” is intended to refute: that the colored soldiers “fought their way to light[-brigade status]” as opposed to the “light” of freedom. Instead of underwriting freedom, that is, glory and honor become consolation prizes in its absence. Even as “The Colored Soldiers” seeks to reclaim the “Light Brigade”’s triumphalism, then, it is haunted by the poem’s negativity.

Another irony in Dunbar’s use of “The Charge of the Light Brigade” to figure permanence is that the poem’s currency had gotten debased over time. Thanks to its enduring place in the curriculum, “The Light Brigade” remained familiar throughout the second half of the nineteenth century; at the same time, though, it became increasingly subject to promiscuous, casual, and irreverent citation and appropriation. This is as true in the African American press as in the white press. The poem’s decline is uneven, but we can get a sense of it from an 1882 article in the African Methodist Episcopal Church’s widely read Christian Recorder. Mocking the supposed Negro love of titles, a reporter complains that a recent convention “to discuss the moral, social and political condition of the negro” devolved into a display of what he calls “titular twaddle”: “Professors to right of us, professors to left of us, professors in front of us volleyed and thundered.”70 Thus does glory fade, not into oblivion but bathos.

This decline notwithstanding, “The Charge of the Light Brigade” also appears in the most influential work produced in this period by an African American writer, W.E.B. Du Bois’s The Souls of Black Folk (1903).71 Like Dunbar, Du Bois turns to “The Light Brigade” when grappling with the failed promise of Reconstruction.72 True to Du Bois’s more negative vision, however, it is precisely the poem’s negativity that he calls upon. Whereas Dunbar asserts that “the Blacks enjoy their freedom,” Du Bois counters that “despite compromise, war, and struggle, the Negro is not free.” Discussing the Freedmen’s Bureau, established at the end of the Civil War to promote the rights and welfare of freed slaves, Du Bois defines its “legacy” as “the work it did not do because it could not.”73 Defending nonetheless the efforts of the Freedmen’s Bureau and its first commissioner, Oliver Howard, he writes:

nothing is more convenient than to heap on the Freedmen’s Bureau all the evils of that evil day, and damn it utterly for every mistake and blunder that was made.

All this is easy, but it is neither sensible nor just. Some one had blundered, but that was long before Oliver Howard was born; there was criminal aggression and heedless neglect, but without some system of control there would have been far more than there was.74

As expansive as it is brief, this allusion transforms Tennyson’s blunt characterization of a miscommunicated order into a tragicomic euphemism for one of the most momentous events in world history, the establishment of slavery in the New World. The victims of this “blunder” number in the millions, not the hundreds. Such a shift in scale has the effect of parochializing the concerns of “The Charge of the Light Brigade,” even as the very act of alluding to the poem reflects its lingering cultural presence.

Du Bois’s unmarked allusion to “The Charge of the Light Brigade” is in many respects quite different from James McCune Smith’s sustained engagement with the poem a half-century earlier. In an uncanny turn of events, however, the afterlife of the very passage containing Du Bois’s citation ends up repeating the dynamic of cross-racial plagiarism McCune Smith described. As Du Bois gleefully documents in a 1912 editorial in The Crisis, the winning entry in a contest sponsored by the United Daughters of the Confederacy for the best essay on the Freedman’s Bureau by a University of South Carolina student included long passages lifted verbatim from Du Bois’s chapter (or the Atlantic article where it first appeared). “There is nothing to mar the fulness of the tribute here involved,” Du Bois exclaims, “not even quotation marks!”75 McCune Smith’s scenario of a white writer stealing from Africans to create “The Charge of the Light Brigade” thus returns in the form of a (presumptively) white writer stealing an African American’s text citing the same poem.

In this chapter and the preceding one we have seen Victorian novels and poems serving variously as topics for discussion, topoi, and shared points of reference within African American discourse and print culture. In this chapter, we have also seen that the African American engagement with a particular Victorian text could extend over time and, further, take a shape or form a pattern that begins to look less like a series of isolated actions than a self-conscious tradition. The remaining chapters of this book will continue and expand the diachronic dimension of the story I am telling. We shall see that Victorian literature—and a small subset of Victorian authors and texts in particular—was called upon repeatedly and revealingly by African American authors and editors through the turn of the twentieth century (and therefore the end of the Victorian era itself) and into the period of the Harlem Renaissance. Those writers with the most sustained, generative, and complex relationships to Victorian literature are now recognized as major figures in the development of the African American literary tradition, albeit largely despite, not because of, these relationships: Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, Charles Chesnutt, and Pauline Hopkins as well as Du Bois. And while these writers’ attention to Victorian literature has been largely denigrated and neglected, we will see that they themselves often inscribed this attention in ways that suggest an awareness of similar attention on the part of earlier and contemporary African American writers.

Tennyson himself, it turns out, is by far the most ubiquitous Victorian author in this African American tradition. While the presence of “The Charge of the Light Brigade” wanes somewhat, a number of other poems take its place—chief among them, perhaps, the one we saw (in the introduction) Anna Julia Cooper quote so prominently in A Voice from the South: In Memoriam.76 In general, though, these later engagements with Tennyson lack the singleness of focus we have seen on display in this chapter: typically, more than one poem by Tennyson will be in play, as will more than one Victorian author. For that reason, rather than isolate this strand for chapter-length treatment, I will weave it into the broader discussion in the second half of the book.

First, though, I will turn to the third Victorian author who, along with Tennyson and Dickens, plays the most significant, reciprocally revealing role in the African American literary tradition: George Eliot. As we have seen, Bleak House directs attention away from Africans and African Americans, and “The Charge of the Light Brigade” stages a retreat from race; by contrast, the most frequently and elaborately African Americanized text by Eliot makes race (although not African Americans) a central concern. While an elective affinity with Eliot may thus seem unsurprising, it has gone almost entirely unexplored. As we shall see, the forms taken by the African American engagement with Eliot shed new light on her own career-long exploration of racial affinities and affiliations—elective, surprising, and otherwise—as well as those of her African American repurposers.