Chapter 1

Piers Plowman Before 1400: Evidence for the Earliest Circulation of A, B, and C

William Langland was finished with Piers Plowman A by around 1370, but its earliest extant manuscripts are no earlier than about 1390.1 Such gaps are not unusual for Middle English poetry,2 but the existence of Piers Plowman in so many versions, and the indications that major figures like John Ball and Geoffrey Chaucer knew one of those versions as early as 1380, render our response to this gap in particular especially urgent. The predominant narrative of the poem’s early existence—that the B version was the only one available by that date—is in effect a gloss on that gap, one that assumes that A manuscripts from the 1370s do not survive now because they did not exist in the first place. But that narrative passes in silence over the fact that no B manuscripts survive from that era either. At least for the sake of consistency, one might hope for the acknowledgment that the dates of extant manuscripts indicate nothing about the form in which Piers Plowman existed by 1380.

For a much fuller mapping of the earliest circulation of Piers Plowman we need to turn to another major and widely available, if also widely neglected, area of knowledge: the status of the texts within these manuscripts. This material, I will argue, directs us to the conclusion that, contrary to widespread belief, Piers Plowman A achieved a substantial circulation from very early stages, the B version in contrast remaining dormant until readers and scribes had embraced the final, C version. I then turn to the external indications that have a bearing on the question of the B version’s early availability, found in works written by a pamphleteer, a poet, and a preacher c. 1381–82; again, I will show that A is the most likely source of their knowledge. This chapter sets in train the central theme of this book: the earliest production and transmission of Piers Plowman were nothing like what we have assumed.

Evidence for the Early Circulation of Piers Plowman A

The gap between the composition of Piers Plowman A and its surviving manuscripts invites two competing interpretations. One is best articulated by Ian Doyle, who finds it “not surprising that the earliest copies of Langland’s A text, composed in the 1360s and perhaps slow to be multiplied, but increasingly sought after, should have been lost, as the other longer texts became available for preference, combination or conflation.”3 This approach has the advantages of speaking to the character of A in particular, as such forces of destruction would not apply to B or C, and of being immune to disproval. Only the sudden revelation of dozens of ancient A-version manuscripts would alter the point, and even then it would still seem likely that innumerable others were victims to the desire for longer versions. Still, Ralph Hanna, in voicing the alternative approach, goes so far as to censure Doyle’s as one that “simply ignores the visible historical evidence,” which instead, he writes, “suggests that this version had absolutely minimal circulation before about 1425.”4

Hanna immediately qualifies this remark, though, acknowledging that three A-version manuscripts are “certainly fourteenth-century”: Cambridge, Trinity College, MS R.3.14 (T; 1 in our running count of pre-1400 manuscripts); the “Vernon” text, in Oxford, Bodleian MS Eng. Poet. a.1 (V; 2); and the infamous MS Z (Oxford, Bodleian MS Bodley 851; 3).5 The “evidence for other pre-1400 copies” prompts a further retreat:6 the exemplar or ancestor shared by Bodleian Library, MS Rawlinson poet. 137 (R) and Oxford, University College MS 45 (U), whose reference to Richard II as monarch in its passus 12 indicates its pre-1399 date (4; Schmidt’s u);7 the copy available to Scribe D as he wrote the Ilchester manuscript (J of C), whose Prologue incorporates material from A and a variant C tradition (5);8 and that used by the scribe of the common archetype behind the BmBoCot group (6).

Hanna’s list of now-lost A manuscripts is very selective. Many more than these three are necessary to explain the surviving affiliations, as the accounts of George Kane and A. V. C. Schmidt in their respective editions make clear. It is true enough that manuscripts cannot be dated very precisely, “erroneous readings” are the products of subjective reasoning, the results are inevitably incomplete, and stemmata are of limited use, at best, to editors. But as Hanna elsewhere says, “However editors may use stemmata in textual reconstruction, the diagrams themselves do represent historical processes, and processes capable of some degree of specification.”9 A little common sense, such as not assuming a direct correlation between the number of lost and extant manuscripts in any given version, will more than balance any potential problems.10

For beginners, a quick glance at Schmidt’s diagram of the A tradition reveals the existence of nine additional lost copies, all those in the lines of descent culminating in MSS T and V.11 MS T’s ancestry includes TH2 (7); t (8), ancestor of TH2Ch; d (9), ancestor of TH2ChD; r1 (10), exemplar of d and u; r (11), exemplar of r1 and r2 (the latter being the ancestor of VHJLKWNZ); Ax (12), ancestor of all surviving copies; and A-Ø (13), a pre-archetypal copy.12 And MS V’s ancestry comprises v (14)13 and r2 (15). But even this is a partial tally. Kane says that the corrupted character of V “presuppos[es] a considerable number of stages of transmission,”14 a point supported by M. L. Samuels’s remark that some of V’s dialect forms suggest that, unlike others in the A tradition, including H, “it was derived from an eastern exemplar,”15 very unlikely to be v itself, and thus constituting item (16).16 The affiliations of the text of folios 124–39 of Bodley 851 (“the Z version”) with MSS (E)A(W) MH3, the m group, show that m or its ancestor must predate that very early manuscript, thus constituting item (17).17

And there is no reason to restrict ourselves to the affiliations of the relatively complete A-version manuscripts. Item 6, the copy behind the A matter in BmBoCot, bears a close relation to the t-group, especially MS H2. These affiliations are most probably explained, as Carl Grindley has shown, by positing an exclusive ancestor (18) of 6 and 7, with MS T’s correct readings against H2BmBoCot representing scribal improvements to a faulty exemplar’s readings.18 And Russell and Kane characterize the Ilchester MS’s A frame text, copied from 5, as “ordinary: in about twenty departures from the adopted A text it enters more than a dozen different agreements.”19 But this is misleading, for its mere fifty-two lines share six errors with the mid-fifteenth-century MS W alone, and another three with W and one other witness or group.20 This is about the densest rate of error in the surviving manuscript record.21 Unless W descends directly from the very exemplar behind MS J, and unless that exemplar was a direct copy of Ax, by the 1390s at least one now-lost generator of the family to which MSS W and J belong, number (19), must have been extant.

So wild are the A-text affiliations that nearly every member tends to follow the pattern represented so far by MS V. Hanna, contradicting his earlier stern judgment, has pointed out that the “impenetrable dialectal mixtures” of the A manuscripts constitute a state of affairs that “suggests that many manuscripts are the surviving product of several generations of copyings in diverse locales.”22 And while these “generations” are stages of copying in lines of transmission rather than fixed periods of time, it takes time for manuscripts to be copied, travel, and find new scribes and audiences. All of which is to say that the figure of nineteen now-lost A manuscripts is the result of the most efficient explanation of textual affiliations; only once, in the case of MS V, did we even begin to make use of the dialectal data here cited by Hanna. The wildness of the A tradition’s textual record alone, not to mention its impenetrable dialectal mixtures, should have put the restraints upon all the rhetoric about its supposedly late circulation.

It remains unclear how long before 1400 or so the A tradition achieved wide circulation. MS T’s distance from Ax—some six generations of copying—does not necessitate, even if it might imply, a very lengthy period of time. The earliest surviving manuscripts with A material are probably Vernon and Ilchester, but they might be only three or so generations from the archetype. It is clear, though, that since 1960 plenty of evidence for Piers Plowman A’s substantial fourteenth-century readership has been available. Readers have on the whole ignored this remarkable body of data, focusing their energies and anxieties instead on the established Athlone text. But it enables a much more thorough mapping of the shady terrain in which Piers Plowman first circulated than do the dates of the extant witnesses.

Lost: Piers Plowman B

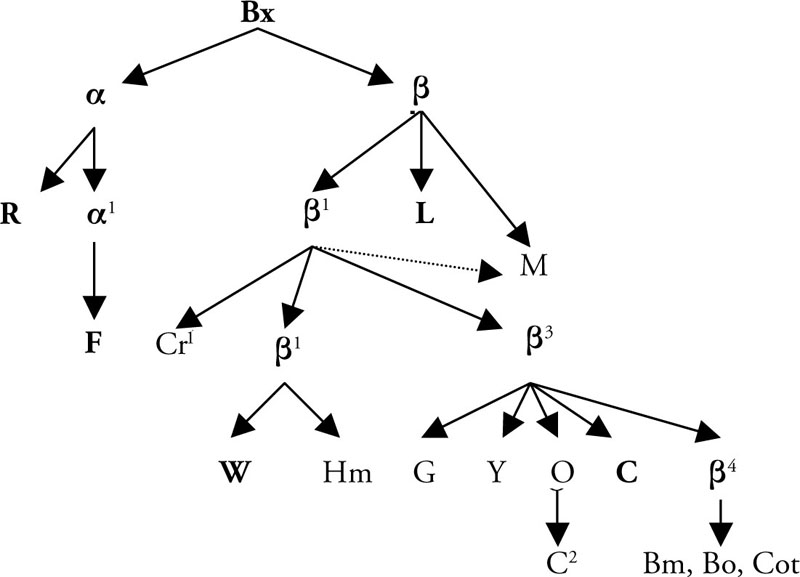

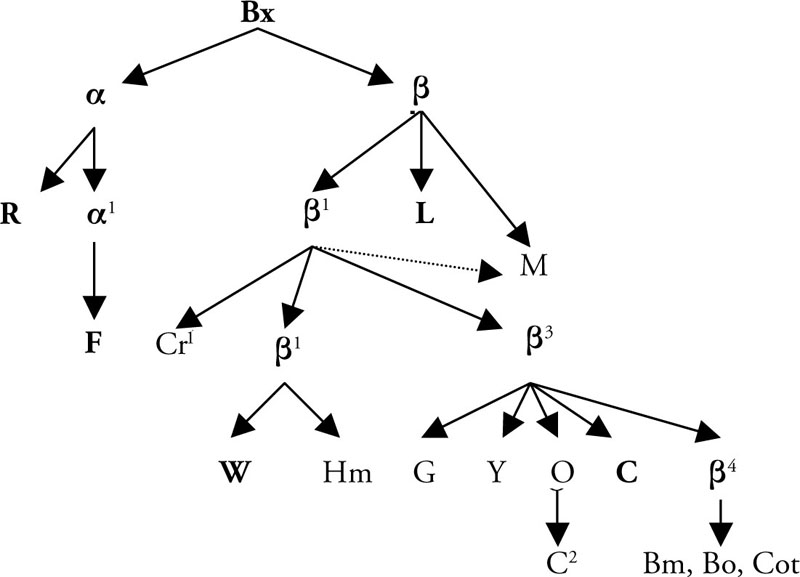

The corollary to the belief that A had no public life in the fourteenth century is the assumption that B, by contrast, “quickly achieved something like a canonical status,” as Robert Adams has put it.23 Yet the earliest extant B manuscripts, like those of A, date to the 1390s.24 More problematic is that the B tradition’s “tightly bifid stemma” below, which Adams produced on the basis of work done by the editors of the Piers Plowman Electronic Archive, is suggestive, as he says, of “a tradition that never consisted of many manuscripts.”25 A total of eight now-lost manuscripts (in bold: Bx, two in the α family, five in β) are necessary to explain the relationships among the survivors; see chart.26

All eight lost B-tradition manuscripts, and at most about five extant ones, are likely or possible products of the 1390s. Given the tenor of most discussions of the early transmission of Piers Plowman, the fact that the number of pre-1400 manuscripts necessitated by the A tradition’s affiliations is about 50 percent greater than this figure might seem surprising in itself. But most striking here are how well defined the B tradition is (quite opposed to A), and how late it came into being. Two of the extant fourteenth-century productions, plus one dated to the beginning of the fifteenth century (B.L. MS Add. 35287 [M]), are only two generations of copying removed from the archetype.

The notion that B achieved something like a canonical status between its postulated date of completion (c. 1377–78) and, say, the Rising of 1381, then, is an assumption rather than a postulate based on textual evidence. Schmidt is the only critic to have explained his belief that Bx was a product of the late 1370s in positive terms, and he carefully presents the case as a matter of probabilities and presumptions: “it is likely to be the longer version that the peasant rebel leaders alluded to in 1381,” he claims, on which basis he later says that B’s “archetypal manuscript was presumably generated only a couple of years before the Rising [of 1381].”27 The substance of this proposal, Ball’s presumed knowledge of B, will occupy us below; but the fact remains that the only pre-archetypal manuscripts inferable on textual grounds are the C reviser’s B manuscript and the copy to which the F or α1 scribe had access, which the Athlone account necessitates. And some critics have cast doubt upon the existence of even these two, particularly with regard to F.28 Robert Adams has interpreted the “multilayered complexity of dialects” in the B tradition as “indicative of a wider circulation (and more extensive recopying) than that achieved by the C version,” but in fact there is no compelling reason to attribute these layers to any more than the three-plus post-archetypal generations represented above.29 Anyone eager to use this evidence to bolster the count of early B copies, if playing fair, will need to follow suit with regard to the “impenetrable dialectal mixtures” of the A manuscripts.30

In sum, if the messy state of affairs in which the A version survives looks exactly like the result of a tradition whose ancestors had disappeared, the cleanness of B’s makes it look as though it never had such ancestors.31 This cleanness, and not the absence of early A copies, presents the most pressing question about the earliest transmission of A and B. Almost fifty years ago in Sydney, George Russell spoke to the heart of the matter: “Why is it,” he wondered,

that that version of the poem which almost all modern readers and critics agree in judging to be the most impressive, was the version whose lines of survival were most tenuous; which, in fact, seems to have escaped extinction only by the chance survival of a single manuscript? It may be that this was a mere matter of accident: but the facts of the A- and C-descent suggest that this is unlikely. If the short and essentially incomplete A-text finds readers and copyists in numbers from the beginning, and if the same is also true of C-, why then should B- not find them?32

By way of explanation Russell proposed that B, “for various reasons, mostly political, religious and ideological, was either called in by the author or was suppressed by others,” of which destructive program Bx was a chance survivor.33 But what mechanisms could have enabled so thorough a suppression? If this version was circulating widely, how did Langland or these other censors know how many copies were extant, where to find them, and how to prevent further copying?34 A more efficient explanation, if one less conducive to most narratives of the history of Piers Plowman, is that Langland’s own B version achieved absolutely minimal circulation, if any at all, before c. 1395, and not very much between then and 1550 either.

The Early Proliferation of the C Version

The most likely scenario is that readers’ quick embrace of Piers Plowman C led to the release of the dormant B version.35 This claim follows from the fact that C’s transmission history differs so starkly from those of A and B. Far more of its manuscripts predate 1400, and four manuscripts from Schmidt’s collective sigil y (XYHJ) have excited particularly strong interest. These texts exhibit both dialectal features very close to those presumed to be Langland’s, which many critics have taken as evidence of his whereabouts when he composed C, and codicological and paleographical characteristics very similar to those of the London-based productions associated with Gower and Chaucer.36 In two of these, San Marino, Huntington Library MS Hm 143 (X) and the Ilchester manuscript (J), critics have found evidence of “some direct connection to the author.”37 Such judgments, however, have not taken account of these surviving manuscripts’ positions within the C stemma. Ten surviving witnesses—three of these four (XHJ), plus MSS UTPEVMK—predate 1400, as do some fourteen more now-lost copies in Schmidt’s chart.38 MS X alone, like MS T in the A tradition, is some five to eight generations of copying removed from Langland’s holograph.39 Even if Langland was alive when C entered circulation, the chances of his survival diminish with each successive generation. We should be wary of any placement of MS X or J in close physical or even textual proximity to the author.

This body of data should also prompt a fresh analysis of our methodologies of dating the versions. In recent years, a terminus a quo of 1388 for the completion of C has gained widespread support on the basis of Anne Middleton’s argument that the apologia pro vita sua (C 5.1–104) stages an interrogation under the 1388 Statute of Laborers.40 The most surprising of this proposal’s many adherents is George Kane, who adds that “the latest topicality in C appears to be reference to the king’s implacable hatred of Gloucester and the Arundels after the dissolution of the Merciless Parliament (C 5.194–96),” that is, the months following June 1388.41 If so, we must marvel at the extraordinary rapidity with which early scribes set to work on C. Although this scenario is not impossible, it is much more difficult than has been acknowledged by most accounts of C’s early production, which seem to assume that Cx or other early manuscripts were available for copying at will by any given fourteenth-century scribe.

The Evidence of Allusion?

Kathryn Kerby-Fulton’s 2006 study Books Under Suspicion represents a major recent trend in claiming to identify allusions to the B version in works composed by 1382 at the latest. In the lines “With an O and an I, Si tunc tacuisses / Tu nunc stulto similis philosophus fuisses” from the 1382 broadside “Heu quanta desolacio” (which includes the phrase “rogo dicat Pers”), she finds a probable reference to B 11.416α, “Philosophus esses si tacuisses,” “you might have been a philosopher, if you had been able to hold your tongue”;42 later, she describes Chaucer’s “Thoo gan y wexen in a were” (House of Fame, 979) as a “deliberate echo” of Will’s “And in a wer gan y wex” (B 11.116).43 Kerby-Fulton finds “the hints of ‘Heu’s’ Langlandianism … significant since its date is so early in the period of B transmission.”44

Such proposals are “soft,” as it were, in occupying no more difficult a place than would the idea that, say, a given Shakespearean phrase comes from Chaucer. They can be adjudicated on the terms in which they are presented—linguistic, thematic—without regard to questions of transmission. The fact that no evidence supports the notion of B’s transmission by this stage, though, makes for a dilemma. Can we elevate their status to “hard,” constituting positive evidence, rather than derivative support, for B’s early circulation? Some have had no trouble doing so: one critic announces that a study finding B’s influence in John Ball’s letters “establishes that June 1381 is a terminus well post quem for the B version”;45 another says that a similar and separate claim regarding the House of Fame “demonstrates that the B text was probably circulating and known about in London at the time when Chaucer was living in Aldgate.”46 The assumption, in other words, generates the proposal, which in turn becomes the evidence upon which the assumption was presumably based in the first place. While those readers predisposed for whatever reason to believe in B’s transmission c. 1380 might well cite such claims as supporting indicators, I think it is fair to say that, when analyzed apart from that assumption, they remain securely in the “soft” category. Each such claim is either more easily explicable by recourse to other modes of influence (if any at all) or contradicts other, equally persuasive proposals, tossing us back to the very category of evidence we were seeking to bypass.

The appearance of the Latin item shared by “Heu” and the B version in both Odo of Cheriton’s thirteenth-century Fables (as I have recently discovered) and John Bromyard’s mid-fourteenth century, and hugely influential, Summa Praedicantium (as Alford pointed out and Kerby-Fulton acknowledges), for instance, indicates a mutual indebtedness to the homiletic tradition c. 1380 rather than one’s reliance upon the other.47 Much more promising is the parallel between the protagonists of Piers Plowman B and the House of Fame who “waxed in a were,” that is, “grew into a condition of doubt or anxiety.”48 Yet Paul and Dante, not Langland, are the most obvious models for Geoffrey’s situation here,49 and only slightly less immediate is Boethius, on the dreamer’s mind at this point (HF 972), who also “leaves us in fact with much the same kind of doubt that Chaucer now confesses to,” says J. A. W. Bennett, citing our line.50 When Chaucer wrote were, he was probably aiming for elegance, given that the alternative, from Philosophy’s diagnosis of Boethius’s affliction, was this: “thilke passiouns that ben waxen hard in swellynge by perturbacions flowyinge into thy thought.”51 Whichever option he chose, he would have almost certainly needed to use the term wax, which appears juxtaposed with these phrases not just in the House of Fame, the B version, and Boece, but also in Chaucer’s account of poor Hypermnestra, who “waxes” cold when she “falls” into a were:

As colde as eny froste now wexeth she

For pite bi the herte streyneth her so

And drede of deth doth her so moche wo

That thryes down she fill in suche a were.52

Both Langland and Chaucer are making best use of a psychological vocabulary that is already inherently alliterative. There is no need to attribute the parallels of these lines to anything other than this common body of sounds and ideas.

This is somewhat unfair to Kerby-Fulton’s proposal, which appeared in a critical milieu that not only took B’s earliness and A’s belatedness for granted, but also had been deeply influenced by Frank Grady’s argument that the House of Fame relied on B. Both poems, he says, interrogate authorities and authoritative discourses, use signatures at moments of poetic transition, and are potentially endless.53 Whatever the strengths of these suggestive parallels—many of which would fit A, too—they run up against Helen Cooper’s equally compelling claim that the General Prologue to the Canterbury Tales (1387 at the earliest) adopts the A version’s Prologue as a model.54 Grady’s Chaucer was particularly taken by the unresolved conclusion of B (i.e., passus 20) in the late 1370s, but Cooper’s remained ignorant of B passus 19–20 in the 1380s.55 Any adjudication would need to take recourse to other evidence—showing that Grady does not “demonstrate” B’s availability in the 1370s. The force of George Economou’s comments is clear: “wherever critical interpretation leads on the fellowship of Chaucer and Langland, it cannot avoid the mediation of ongoing bibliographical bulletins. Its steps into new pastures will always be dogged or herded, so to speak, by concomitant movements concerning the poems’—mainly Langland’s—provenance and dispersal.”56

The case of John Ball is especially pressing. For one, his letters inciting the Rising of 1381 refer directly to “Peres Plouȝman” (“Heu”’s “Pers” is the closest analogue above). More important, it is almost universally accepted that this appropriation of his poem was a primary instigator of the C revisions.57 Ball’s letter to the commons of Essex, as recorded by Thomas Walsingham, is the most fruitful of the Langlandian letters:

Johon Schep … biddeþ Peres Plouȝman go to his werk, and chastise wel Hobbe þe Robbere, and taketh wiþ ȝow Johan Trewman, and alle hiis felawes, and no mo, and loke schappe ȝou to on heved, and no mo.

Johan þe Mullere haþ ygrounde smal, smal, smal;

Þe Kynges sone of hevene schal paye for al.

Be war or ȝe be wo;

Knoweth ȝour freende fro ȝour foo;

Haveth ynow, & seith “Hoo”;

And do wel and bettre, and fleth synne,

And sekeþ pees, and hold ȝou þerinne;

and so biddeth Johan Trewaman and alle his felawes.58

Attempts to identify the version known to Ball, whether directly or via oral transmission, falter on the fact that all three of the relevant phrases (four, if one counts “John Sheep” as a reference to A Prol.2/B Prol.2) appear in both A and B: not just Peres Plouȝman, but also Hobbe the Robbere (A 5.233, B 5.461) and do wel and bettre (Dobet: A passus 9–11, B passus 8–14).

Yet most recent commentators simply accept as a given that Ball knew the B rather than the A version.59 Some of those who cite the lateness of A manuscripts, such as Steven Justice, Ralph Hanna, and A. V. C. Schmidt, are also advocates of Ball’s knowledge of B (as they must be), but as we have seen the textual indications in fact point toward the opposite conclusion. The case for B, if it is to stand, must thus rely entirely on much more impressionistic responses to the letters. þe Kynges sone of hevene, maintains Schmidt, “is a characteristic group-genitive phrase little instanced outside the poem (B 18.320 //), and its conjunction here with the idea of ‘paying for all’ will recall the argument of B 18.340–41.”60 So it might in the minds of readers predisposed to believe Ball knew B, but others might take more convincing. The concept of Christ as son of the king of heaven is pervasive, and its expression via this grammatical construct is not as rare as Schmidt suggests; Richard Rolle, too, refers to “Criste, the keyng sonn of heven.”61 Whatever affinities the phrase schal paye for al has with the argument of lines 340–41, “Ergo soule shal soule quyte and synne to synne wende / And al þat man haþ mysdo, y man wole amende,” seem to me very general as well. In this phrase George Kane finds a different echo, of “Ac for þe pore y shal paye, and puyr wel quyte here travaile” (B 11.195), which is even more distant.62

Kane cites another parallel, between sekeþ pees, and hold ȝou þerinne and

Quod Consience to alle cristene tho, “my consayl is to wende

Hastiliche into unite and holde we us there.

Preye we þat a pees were in Peres berne þe Plouhman” (B 19.355–57)

which seems more promising.63 The appearance of Ball’s injunction immediately after the dowel tag seems to offer support—but, again, all this is also in Psalm 33:15, “recede a malo et fac bonum, quaere pacem et persequere eam” (“turn away from evil and do good: seek after peace and pursue it”).64 Such phrases are everywhere in medieval devotional writings.

The same problem attends Steven Justice’s extraordinarily influential assertion that Ball knew a particular passage of the B version. Attempting to understand Walsingham’s claim that Ball taught “that no one was fit for the kingdom of God who was born out of wedlock,” Justice cites Wit’s invective against those born out of wedlock: “Aзen dowel they do yvele and þe devel plese” (B 9.199): “Here are Ball’s bastards.”65 Yet the teaching that those born out of wedlock are unfit for the kingdom of God is biblical: “A mamzer [KJV: bastard], that is to say, one born of a prostitute, shall not enter into the church of the Lord, until the tenth generation” (Deut. 23:2).66 In any case, this line appears in A as well (10.213),67 so the reasons for Justice’s nomination of B as Ball’s source cannot be found here. But the assumption that the line’s B rather than A appearance incited Ball prompts Justice to claim that “Ball found the epithet that dictated” the execution of Simon Sudbury, the archbishop of Canterbury, in Wit’s claim that “Proditor est prelatus cum Juda qui patrimonium christi minus distribuit” (“He is a traitor like Judas, that prelate who too scantily distributes the patrimony of Christ” [B 9.94α]). And on the basis of this second assumption he indulges in a third, claiming that the rebel letters revise Langland’s portrayal of the poem as inquiry, as an endless quest, in passus 8, 12, and 20.68

As Justice grants, however, anyone looking to connect bastardy, disendowment, and capital punishment, as does Ball, would find little in Langland.69 What he does not acknowledge is that great riches, of the highest authority, await discovery in the chapters leading up to Moses’ invective against bastards:

Thou shalt bring forth the man or the woman, who have committed that most wicked thing [i.e., idolatry], to the gates of thy city, and they shall be stoned…. Thou mayst not make a man of another nation king, that is not thy brother. And when he is made king, he shall not multiply horses to himself…. He shall not have many wives, that may allure his mind, nor immense sums of silver and gold…. But the prophet, who being corrupted with pride, shall speak in my name things that I did not command him to say, or in the name of strange gods, shall be slain. (Deut. 17:5,15–17; 18:20)

St. Paul strikes a very similar chord in warning that “neither fornicators, nor idolaters, nor adulterers, nor the effeminate, nor liers with mankind … shall possess the kingdom of God” (1 Cor. 6:9–10; cf. Eph. 5:5). Langland’s own interest in this is suggested by his citation, just before the passage Justice quotes, of 1 Corinthians 7:1–2, “Bonum est ut unusquisqui uxorem suam habeat propter fornicacionem” (194α). Isabel Davis nominates this letter as a likely source for Wit’s discussion of marriage.70 And Bromyard’s citation of both the Deuteronomic and Pauline materials in the entry on luxuria in his Summa Praedicantium is especially suggestive.71

Ball is not speaking Langland, then; rather, both Ball and Langland are speaking St. Paul, most likely via a conduit such as Bromyard. Invectives against sexual misconduct pervaded medieval religious and ethical thought. A parallel debate about the relationship between Ball’s letters and Piers Plowman will bring my objection into focus. At least three commentators have argued that the absence of wrath from the lists of the deadly sins in both Ball’s first letter and Piers Plowman A, but not B, “points towards the A version as that known to the participants in the rebellion.”72 To this Jill Mann objects, “given the familiarity of the sevenfold scheme, it is difficult to see why Ball would have shown so slavish an adherence to the A text, especially since the six-line poem on the sins does not show any verbal influence from Piers Plowman.”73 Just so—and given the familiarity of Deuteronomy, Paul’s letters, and sermonic materials, it is difficult to see why Ball would have shown so slavish an adherence to the B text, especially since the sermon on bastards does not show any verbal influence from Piers Plowman.

John Ball’s writings have turned into a hothouse of allusions, in which evidence keeps sprouting without having established roots in an explanation of why Ball, who had long been preaching and taunting his ecclesiastical adversaries, would suddenly need Piers Plowman for such bedrock ideas as “doing well.” Thus while Richard Firth Green cites do wel and bettre as “confirmation, if any were needed, that this is a conscious Langlandian allusion,”74 those not as invested in identifying Ball’s reading of the poem could just as easily see it as a conscious allusion to St. Paul’s “both he that giveth his virgin in marriage, doth well; and he that giveth her not, doth better” (1 Cor. 7:38), the verse in which Isabel Davis finds Langland’s inspiration for Wit’s definition of Dowel. We ourselves might do well to heed Margaret Aston’s revival of an earlier approach to the topic:

“Lokke that Hobbe robbyoure be wele chastysed….” Of course it was possible to apply the words to Robert Hales, but the alliterative Rob or Hob Robber was an ancient and familiar figure. Should we not be wary (pace today’s literary scholars) of assuming that Piers Ploughman, who appears alongside Hob Robber, is a reference to Langland’s poem? The words “do well and better” scarcely prove the point, since “Do well” had its proverbial context long before the poem appropriated it. The figure of Piers the honest ploughman may already have been an alliterative type (as much as Tom Tinker, Miles Miller and Piers Potter) called on by John Ball as by Langland for their different purposes. This is an unfashionable view, but it had the support of C. S. Lewis.75

In light of the strength of her objection, and of the fact that the only items with strong Langlandian resonances appear in A and are traceable back to Bromyard, St. Paul, and the like, attempts to depict Ball as a sophisticated reader of the B version go far beyond what the evidence will support. The most these letters tell us is that some catch-phrases from A might have made their way somehow to Ball; and they might not even tell us that.

Conclusion: The Earliest Circulation of Piers Plowman

It is not impossible that Ball or Chaucer could have read the B version by c. 1380, just much more likely that they knew A, if any version at all. The quick promulgation of C (if indeed it is to be dated to c. 1390)—an average of almost one copy a year in each line of transmission, culminating in the surviving fourteenth-century manuscripts—underscores, as does the A line before it, just how shadowy the pre-1390 B tradition is by comparison. Over the course of this book the belief in an integral pre-1390 Piers Plowman that looked something like our modern “B version” will only recede farther from the realm of reasonability. This statement perhaps appears more provocative than it ought, for my argument will be simply that “Piers Plowman B” as studied today is the product of conflation of the “ur-B” version that Langland wrote c. 1378 (whatever the extent of its circulation) and the earliest stages of C, and as such was representative of a major mode of the poem’s production in the era of C’s initial dissemination, which, crucially, was also the era of Bx. Because critics have always assumed a correlation between the “shapes” of certain of the surviving texts and the “versions” (i.e., what Langland wrote), the textual criticism of Piers Plowman, while among the richest and most advanced in English studies and perhaps beyond, remains in some ways in its early stages. Until it confronts the possibility that Bx, like so many of its chronological peers, was conflated by C materials, even if only to reject it, Langland criticism, not just its textual subfield, will be based more on faith than on evidence.