![]()

2.4.14

‘When did you first see Mrs Thatcher?’

Miss Robbins is the speaker’s name. She holds the letter that I sent her. She screws it into a ball in her hand. She snaps out her question and seems set to snap again, unsettled, perhaps, by the wreckage around her feet, the tottering boxes and tumbling paper piles.

There is unsettlement all around. I am about to be moved from the north bank to the south bank of the River Thames. Only for another five months will I be here.

She stops, unscrews my letter, flattens it between her hands and stares down at the address.

‘Thomas More Square?’

She voices the question mark as taxi drivers do. A square? This is East London where there are no squares of the shape you see in Euclid or the West End. TMS (as we call it) is a tall glass tower, with concrete slabs and a sandwich shop on one side, a road to a housing estate on another and two lower towers completing a shape I cannot name.

We are together looking down at Wapping, the north bank of the Thames that was so notorious a battleground of the Thatcher years. If we push out the boundaries until we find some sort of imaginable square there is first the Highway, the Ratcliff Highway as it used to be called in the days of Jack the Ripper, the press gangs for Nelson’s navy and the marches against Oswald Mosley’s blackshirts. Opposite the crawling Highway of lorries runs the empty, broader river, slow brown in a briefly straight line from Tower Bridge.

In the view through the window in front of me is a press gang of a different kind, a former home of four great newspapers, red brick and glass, fiercely fought for when I arrived there in 1986. Beyond and further in front, if our minds travel far enough, are Essex and the North Sea. Behind me is the slab of stone that gives our address its name, the place where England’s once greatest writer and reader of Latin was executed by an axe-man in the summer of 1535.

‘Thomas More Square?’ Miss R has a list and a chart and asks the question again.

‘I have not been up here long’, I say. For much, much longer I was down there.’ I point to the abandoned offices of The Times, the newspaper through which I first met Margaret Thatcher and which I edited for more than a decade.

‘Who was Thomas More?’ She juts out her jaw as though to say that she has just temporarily forgotten.

‘He hardly matters if you are interested in Margaret Thatcher’, I reply.

‘Tell me anyway’, she says, kicking aside a pile of old books as though clearing a seat in a bar. I offer to find her a chair. She chooses a pile of modern political novels instead.

‘Thomas More’, I respond, ‘was a great man of Latin. He used many of the texts you are trampling on now. But he got his gong in history for being bloody-minded, for burning people who disagreed with him and failing to recognise Henry VIII’s second wife. He lost his head for that.’

She stares straight at me, then down again at my letter to her and beneath it her own letter to me.

‘I know where you are. I know why you are here and where you are going. You know what I want to talk about. When did you first see Margaret Thatcher?’

I wonder if I should ask her to leave. I have other things to do. She is irritating me already. The office seems suddenly hot behind its sixth-floor sheets of glass. Temperature controls, like other controls, are failing as our last months here pass by.

It was last June when she wrote to me first, with questions for her thesis on ‘The Thatcher Court’, questions about the lesser courtiers whom she knew I knew, the ‘Rosencrantzes and Guildensterns’, as she put it, not the Hamlets. Although she wrote a persuasive letter, I was not persuaded at first, only when she wrote again last week. By then I was surrounded by so many relics of her chosen time, so many boxes for the removal men. I was staring for the last time at so many places where those courtiers once came. It seemed wrong to say no.

That may have been a misjudgement. She has cropped hair, a bit of a bolshie look, as we used to say, white shoes and a small recording machine.

‘When did I first see Mrs Thatcher?’ Her eyes are a protest: does he have to repeat every question? Her hands crush our letters back into a ball. She leans forward and looks hard.

‘It was February 1985’, I reply, ‘a few weeks before my 34th birthday. I was a junior editor on the staff of The Times. We had an Editor’s lunch, one of those occasions where politicians can be questioned in conditions of fake friendliness.’

Despite her manner I am trying to be helpful and friendly myself. I don’t know how much she understands.

‘An Editor’s lunch is a chance for quiet exchanges of favours, a story on a rival, a request for understanding about an upcoming problem, deals so quiet that many of those present may not even know they are being made.’

She nods. That is something she thinks she does understand.

‘Margaret did not behave well. It was one of her “remembering the Brighton Bomb” days, or so one of my knowing colleagues said. Or she had just “spoken to poor Cecil Parkinson”: that was another explanation.’

I point outwards, to the ground outside, to the gatehouse that was once a fort.

‘We had not quite arrived at Wapping then but we were on our way. The battles down below between police and strikers, men and horses, newspaper unions and managers, had not yet happened. We soon won’t even be able to see the battlefield. We are leaving soon’, I add unnecessarily.

Miss R stands up from her literary perch and shifts her small weight from left foot to right. She waves me to go on.

‘Margaret was certainly not at her kindest that day. No, we did not discuss murder or adultery, nothing as embarrassing as that. We did not mention the IRA attempt to assassinate her during the Tory Party Conference at Brighton five months before, nor “Cecil’s lovechild resignation” during the same conference the previous year. But a lunching journalist in those days could prosper mightily by pretending to understand the Prime Minister’s moods. Maybe my knowing colleague was right.’

‘What did you talk about?’

‘Her enemies mostly, the people whom she thought should be our own enemies too. No one who worked for a university or the BBC would have overheard us without anxiety.’ I mention those enemies in particular because I am trying to tease Miss R who herself is some sort of historian, part of ‘a project’. That is what she claimed in her letter. But she has a toughness that comes from somewhere very different from here. She is not easily teased.

I am answering the question that I think she has asked. I remember many details of that Thatcher lunch. It was the first of its kind for me. I was new then to the game that Miss R now wants to replay.

She said in her letter that she wanted details. I give her details. ‘The Prime Minister was tugging at her necklace, twisting the clasp to hide the pearl that was stained. She was wearing brown and gold, a dress that could have smothered a small child or curtained a bay window. Britain’s first female Prime Minister wore an acidic scent which, if it were a wine, would have been corked, but as a perfume was the spirit of Christmases long past. She looked and spoke like a vinegary sponge.’

‘How did you respond?’

‘There were about eight hosts around the table, the Editor of The Times at that time (his name was Charles Douglas-Home), and the heads of our main departments. Sycophancy or silence were the only choices on the menu. Most of my colleagues chose the sycophancy. As the most junior I like to think that I picked the silence but I cannot be sure. Once her enemies had been dispatched, the ingratitude of friends occupied much of the time between the Marks & Spencer melon balls and the mints.’

She checks that the numbers are changing on her machine as once reporters used to check the whirring of tape.

‘The knowing colleague whispered that the melon balls were the same as those we had endured a few weeks before with the Irish Taoiseach, Garret FitzGerald. Mrs Thatcher heard only the word FitzGerald and frowned. She liked neither him nor the pale green fruits and changed the subject.’

‘“What shall I say when I address a Joint Session of Congress in Washington next week?”, the Prime Minister asked.’

‘“Tell them that you are the same exciting and radical woman that they fell in love with when you were first elected five years ago”, said the lizard on my left, a man whose fragrance was as fresh as the Prime Minister’s was not. This was the Business Editor, Kenneth Fleet.’

‘Mr Fleet was a man of the smoothest confidence, my first departmental boss. Before I arrived in newspapers I had never met anyone like him. He lost his way only when he starred in advertisements for Prudential Insurance.’

Miss R does not laugh. Her face has turned away. She looks out towards the faraway sea – away from the site of Thomas More’s execution on Tower Hill, down along the cobbled dockland street, up to the East London sky to the tower blocks and churches. She looks back at me across the crowded office carpet, the boxes awaiting the removal men, this floor-scape today like an architectural model of the buildings outside.

Her eyes say that this is not what she wants to hear but that she will hear a bit more anyway. I recognise that look. I remember looking that way when I first asked questions for a living myself, asking questions that some superior wanted to be answered. Sometimes an interviewer has to set a subject free. Sometimes we profit from answers to questions that we have not asked. Most often we are too impatient.

‘Listen to me again’, she says, more sharply than an interviewer should. ‘Seeing Margaret Thatcher doesn’t mean meeting her, having lunch with her, talking to her at a party or doing whatever else you did later.’ She speaks as though to a child or a suspect in a murder investigation.

She wants us to get to the menu selections and sycophancy in due time. She wants to get to her four courtiers, one by one. What she wants to know first is something from long before that lunch, something very simple: when did I first see Mrs Thatcher ‘in the flesh?’

She pauses. We both pause. The words ‘flesh’ and ‘Mrs Thatcher’ seem somehow ill matched.

‘Even if it was only the flesh of her face’, she continues as though correcting her own vocabulary.

‘Fine.’ I will tell her. She is pressing me for stories. I understand that. It can be a thankless task.

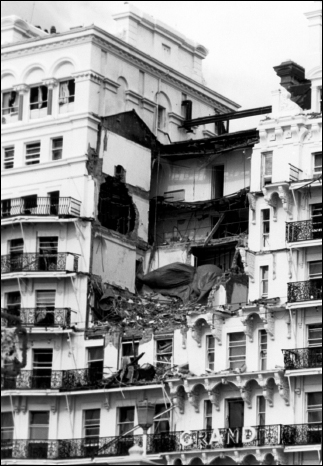

More melon-ball memories from 1985 would have made better stories. The single conversation that I had alone with Mrs Thatcher that day was about Anthony Berry, son of the sometime owner of the Sunday Times, her Deputy Chief Whip and one of those who died at Brighton in that bombing where she was the one intended to die. It was she who raised his name.

I may have been the last man to see Sir Anthony alive, our paths crossing on the stairs at the Grand Hotel after the Party Conference after-parties, his steps directed upwards after walking his dogs by the sea, mine downwards and out into the hotel next door. In the next thirty years I hardly ever saw Margaret Thatcher again when she did not mention this dead heir to a newspaper dynasty.

Sir Anthony was not her own sort of Conservative. He was a privileged part of the party coalition she had to keep together if she could. He was in Brighton that night only by accident, only because someone more important had to stay behind in London to fight the Miners’ strike, the conflict that, in the year before the battles of Wapping, was the biggest item on her inventory of industrial unrest.

Bombing of Grand Hotel, Brighton, 1984

Nor was he well known. He was hardly known to me at all, nothing beyond a smile across a room of wine glasses, Tory Treasurer Alistair McAlpine’s glasses that night of the bomb, one bathtub of champagne bottles and another hiding the explosives. Margaret connected us because she had heard me describe the dogs on the stairs. It was a connection she liked to make.

Miss R looks down again at her recorder. ‘We need to start much further back than the Brighton Bomb.’

She wants me to make her story easy, one thing after another she says. I don’t see how my first mere sighting of Mrs Thatcher is a significant story at all. And I am good at spotting a story.

I will answer her anyway. Miss R is aiming to be a historian and in the job I do now at the Times Literary Supplement we respect historians. We don’t tell them what they should ask and how they should write. Recognising small details that seem unimportant is what great historians do best, journalists too. Bits and pieces can be something or nothing. Every day there are facts that die before darkness.

Before I can follow her direction she suddenly changes it. She says that she is from Essex as though that were suddenly relevant. I say that I was once from Essex too. She points to her white shoes with her first smile, a reminder of once popular jokes about ‘Essex girls’, not the kind I have so far expected her to make. She draws her feet back to the sides of her book pile. She begins her questions again, impatient, Impatience on a Monument you might say.

There is not yet a pattern here. Apart from her claim to profession, I know only how she looks and seems, contained, clawed, mostly careful. Her hair is clipped tight. She is five shelves high when she is standing, maybe about five foot six. I guess that she is about thirty years old but I can do no more than guess. I have checked by Google and there is no trace to guide me. She has not written a book before, or not under the name that she has given.

We stare out away and past one another. I share her appreciation of the view from this sixth-floor window. I look out on it myself as much as I can. Below me sits my landscape of three decades, the places where I used to write about politics, edit The Times, walk, talk and plot with political people, all of the names on Miss R’s list. Now I merely look down on those rooms and roads from this temporary home in a neighbouring tower, from 3 Thomas More Square down on to the gatehouse, to old black bricks, new pink doors and bicycles, and soon I will not even be as close to my past as that.

So yes, I tell her what she wants to know. When did I first see Mrs Thatcher? ‘It was August 1979 in London, four months after she became Prime Minister, five years before she escaped assassination at Brighton, six years before the sycophants’ lunch. It was only a year after my life as a journalist had begun.’

I point down river. ‘I was in Greenwich, South London, not near to the usual Thatcher haunts, not Chelsea, not Westminster, not anywhere I ever heard Margaret say a fond word about, at least not while she was in power, not until, after three election victories, they forced her to resign.’

‘They? Who were they?’

‘Most of them were Tories who never wanted her at all except as a winner of votes they could not win themselves.’

I am wondering if I need to go through her triumphs into Downing Street one by one, 1979, 1983, 1987. Miss R must know these few unassailable facts.

The first win was after Labour’s Winter of Discontent when striking trade unionists let trash pile in the streets and the dead go unburied. The second came after the Falklands War and the third when while winning she lost too much, too many of her friends and something of her mind. Beside crumpled letters and a recording machine Miss R has a calendar of the decade on a spreadsheet, the kind our accountants keep.

‘Finally “they” got her out, forced her to pretend that she wanted a Barratt Home instead, Dulwich not Greenwich, I think, not that she stayed there long. Dulwich? There it is. South and east and down away over there somewhere across the river. As if they could ever get her to spend her time pottering about in Dulwich – or West Harwich, East Greenwich, any of the wiches not far from here beneath the clouds blowing today towards us.’

‘Why were you in Greenwich that night?’

‘I was there to write about a play. I was a part-time critic at the time and the play was called The Undertaking. Its writer was an actor called Trevor Baxter. Its theme was the way that people want to be remembered when they are dead, the very different ways from those that will be chosen by their relatives, lovers and friends.’

‘A little way offstage was a tomb in which the powerful paid handsomely to lie in the uniforms of their lifetime’s passions, their dressing-up clothes not their business suits, a financier in a ballet frock, a general in the loving arms of his batmen, an eminent scientist trussed like a chicken. It was a good story. I remember it now as a good play too but I did not say so at the time. I was a young critic. I thought I should be critical.’

‘Margaret was a new story then but no one thought she would be remembered so much now. No one shouted at her in 1979. The “Poll Tax” was still a 600-year-old error made by Richard II. Not many loved or even hated her. She was new. She was a woman. She was not Ted Heath, the sexless sailor whom, to his unforgiving horror, she had succeeded. There was a wall on stage and, behind it, an orchestra rehearsing a new symphony to celebrate the soul of the European Economic Community, the “soul that is Love”.’

I see a smile. Miss R is perhaps at last hearing what she wants to hear. She sits back on her pile of books, novels at the top, lives of Romans and Tory ministers underneath, and finds that there is a bookcase for her shoulders not far behind. Her feet slide forward. She looks as though she is about to be photographed for a magazine. She almost laughs.

‘Was that the time’, she asks solemnly, ‘when the EEC was beginning to become something less Economic and more Community, when Britain still had its “British disease”?’

‘Yes, exactly. I don’t think I ever enjoyed myself more.’

She adjusts a second electronic device, the pad on which she makes her notes. She straightens her back, a struggle when on a frail support of print. She is speaking as though from a script to a lecture hall of students. I begin to explain but she puts her finger to her lips. That EEC and strikes question, she silently says, is hardly a question at all, not one I need to answer.

So I continue with my answer to the first question, the one she is so insistent on, with what I remember from the day on which I first saw ‘that woman’ as she would become, the woman who afterwards would hover high and low over the buildings down there on the ground. I am looking again out towards Greenwich. The theatre was somewhere under one of those incoming clouds, perhaps beneath that bit of pale blue sky, the bit by the bend of the river.

‘The Undertaking was a play of scenes designed to shock. A Tory lady was looking forward to the “black meat” of “a bulging brute” whom she might enjoy on a trip to Africa, the kind of language that was just still permissible in 1979 as long as the character was a Conservative. Inside the tomb, alongside the grand-passionate and perverted dead, was the dream-delivering undertaker himself, dressed to ape both Leopold II of Belgium and Lenin.’

‘There was also a duplicitous Foreign Office mandarin. To Mrs Thatcher all FO men were “mandarins”, never a term of endearment from that day till the day she died. There was a young girl, apparently buried alive, an old woman newly risen from her grave, and much talk of memory, law and order, more than two hours of it with only the briefest interval.’

‘I was there that night with the man who is first on your research list. Perhaps you know that already?’

‘It was David Hart, political adviser, wealthy fantasist himself and then a very new friend to me, who, soon after the play was over, pointed out Britain’s first female Prime Minister in the back of a low black car. She had just returned from a holiday in Scotland, David told me knowingly. She did not look relaxed but then she hardly ever did, he said. She was dressed in a coat that may have been a dress, with a scarf that scoured her neck as she turned her head, waving to my friend through the grey glass window, or so he said.’

Miss R stands up from her books. ‘I will be back on the next day but one’, she promises.

![]()

4.4.14

The next day but one has now arrived. Miss R has not yet come and it is almost evening.

Maybe I have already missed her. Earlier this morning there was an office outing to the funeral of one of my Times Literary Supplement colleagues, Richard Brain, by name and nature, our foremost stylist in grammar as in dress, whose choice for burial, if he had the chance to make it, would have been a pink cravat and a blue pencil.

Instead of waiting for my interviewer I was waiting for mourners in a monastic relic of the City, remembering little, merely learning that every Charterhouse brother (no sisters allowed) has a number signifying his seniority; and that every death there, and they are very regular, means promotion for those lower down the ladder.

Even on a non-funereal Friday the TLS is quiet at this late afternoon time. It is no trouble for me to be waiting here beside the grey sky, in the same position as yesterday, where I sit most days, writing about the political excesses of two thousand years ago, editing book reviews, and, most important now, separating rubbish from relics for the removal company. Distinguishing between the two is not easy and I have avoided it for decades. Everything that Miss R saw on Wednesday is still here though it will not be here for long.

A single ‘when did I first’ question will not be enough. I know already that she wants to ask about others who linked me and Margaret Thatcher, other questions about Mr Hart and the courtiers I came to call the Senecans. ‘When did you first see Mrs Thatcher?’ is only one of these questions.

I sense that she will keep our appointment and there seems to be no reason not to see her again. I am flattered that a historian would want to see me – or ask when and what I have seen. It is a long time since I have played a part in anything ever likely to be history.

Her first means of arrival should maybe have alarmed me more than it did. She appeared in this office, six floors in the sky, suddenly and without warning, an unusual feat in a modern tower where there are no corridors, few walls and even those are walls of glass. As I will tell Miss R if she asks me, David Hart, her subject and my friend, liked to arrive at his own parties that way. He used secret passages, doors without handles, opened by his touch on a spring, a butler’s lift too, as I recall, adapted so that a single stout host could be among his guests without ever welcoming them.

Miss R wrote in her letter that she wanted to know as much as she could about David Hart, his power and pretensions, his games, his dogs, his pleasure when the young people drank wine that was older than themselves. He seems to be the man at the Thatcher court whom she has studied the most. Then there are the older men, Sir Ronald Millar and Lord Wyatt, rewarded by titles for their labours, and the dark, comic journalist Frank Johnson too, a cast of gilded ghosts who used to strut on the Wapping stage.

I am not sure why she has picked precisely this cast. To me they are united in many ways, most peculiarly by our Latin lessons in a shabby Wapping pub, shared studies of grammar and Seneca, a secret that sometimes surprised even ourselves. Maybe she has somehow learnt about these lessons.

She is a researcher and determined. That much is certain. How did she get in here? She could have been a terrorist, an affronted author, an unpublished poet, a publicist. She could have been someone I offended while editing The Times, a supporter perhaps of the England football manager (Hoddle, yes, that was his name) whom I forced from his job because of an interview in which he professed some primitive form of Buddhism. For years I was abused by friends of Glenn Hoddle. It is easy to give offence as a newspaper editor, necessary I would say.

I tried not to seem surprised to see her, successfully I think. She had our letters but there was no call from Security, no summons to meet her from the lift. Perhaps she came with someone else. This place is not what it was. Surprises happen more often. We are moving very soon. Our boxes are packed. No one cares as much as they once did.

So, when finally she arrives tonight I am not expecting her. I have my back to my desk, my eyes towards East London and the sea and, when I turn back to work, she is simply there. She stands on the thin grey carpet and starts to speak, snapping and smiling by turns. It seems churlish not to return the smiles.

In fact, I am genuinely pleased to see her. Normally I try to avoid the phrase ‘in fact’, even to think it. In matters of English usage I prefer to follow Frank Johnson’s advice, the example of a master stylist, a poor politician but a masterly satirist of politicians, my Latin pupil, the quietest of those four men whom Miss R has mentioned without saying why.

All of them were writers, Sir Ronald of speeches and West End musicals, Lord Wyatt of newspaper columns and diaries, Mr Hart of novels and pamphlets, opinions in The Times if he got the chance, and ‘plays of ideas’ performed at his own expense. That much they most certainly had in common. Sir Ronald was the most successful of them, made famous and rich by Robert and Elizabeth, Abelard and Heloise, and adaptations of political novels by C.P. Snow. The most frustrated was Mr Hart.

Frank Johnson was the strictest of critics. Inter alia (Frank came to love his Latin) he advised all newspaper writers against ‘in fact’, also against ‘genuinely’, ‘recently’ and ‘famous’. This time I am ignoring him.

In fact, Miss R and I become a bit more familiar as we talk, like pet and new pet-owner, not sure of our roles but already sensing something of each other’s insecurities, businesslike but well beyond the smiles of mere business. This time we do not talk for long. We don’t go back to her questions. In fact, she leaves almost as soon as she arrives. We do not kiss cheeks but we do shake hands, only a little awkwardly, as men who know each other do, those of us who are not sure whether we should be shaking hands or smiling on regardless, smiling as though an old conversation has never ceased.

To shake or not to shake? That is a choice I often pondered in my younger days. I hardly ever used to make it correctly. My parents were from the anxious East Midlands, Nottingham lace and Nottingham coal. They brought me up in an Essex community of engineers, of controlled politeness, constrained, without any general confidence, with rules but without a rule for every situation I would later meet.

It is hard to lose the manners of youth. All four of Miss R’s men, the ones she has chosen, used occasionally to chastise me for failures in etiquette, the massively wealthy Mr Hart most of all. Sir Ronald, the would-be wealthy Lord Wyatt and the literary Mr Johnson saw Mr Hart’s own manners as often lacking too.

This evening the crowded office floor does not help. To say goodbye we stretch towards each other like children using stepping-stones to cross a pond. Her thumb is a hook in my hand.

So I am left to myself. I see already that this is going to be a story about me and four men and Margaret Thatcher. Maybe we will go a bit beyond her and into the times of her successors, to John Major and to Tony Blair. She was like a bright sun, hard to see directly, and she cast a long shadow. Throughout her public life her courtiers were like mirrors, each reflecting different aspects of her character, each one worth looking into by those who would understand her.

My story will be of how she exchanged and sometimes failed to exchange her favours. Or, at least, I am happy to make that the story. Miss R will be the one asking the questions. I am merely the interviewee, ready to start in August, 1979, if she wants to start that far back, my last month of ignorance of courtly life.

In that humid summer, five years after ceasing to be an Oxford student, I still wanted to be a classicist of some kind, a writer about Greece and Rome. I knew about the ancient Senecans, colonial lords of Roman Cordoba. I knew nothing much of modern power. I knew a little about Thomas More. I knew only one character even remotely like David Hart – and he was a fictional tycoon called Trimalchio, a creation of satire by one of Seneca’s own fellow courtiers in the age of Nero, a generous host who terrorised his guests with the theatre of food.

Sir Ronald, who was a classicist himself before he sailed to Hollywood, also knew about the billionaire butt of Petronius’s Satyricon, the arriviste who serves fish swimming in sauce like the sea, birds flying from the body of roast beasts, offal that looks like shit. Ronnie thought the comparison to David Hart somewhat unkind. He had never seen David piss into a silver pot and wipe his hands on the hair of the nearest servant. I needed greater experience of modern life.

David was not like Petronius’s monster. Nor, however, Sir Ronald had to admit, was he quite unlike him either. I was keen on Latin novels then. There are not many of them to read. Gaius Petronius was one of the first comic novelists (his grander fans included D. H. Lawrence and T. S. Eliot) and he wrote about food, drink, flattery, death and defecation. He was Nero’s ‘arbiter of taste’, pet prose-master and eventual victim. Or, at least, some scholars think that he was. Some think that there was more than one Petronius. Gaius may not have been the name of either. There is always uncertainty in distant history, almost always too in the kind that is close.

As for Sir Ronald, I saw him as more like Lucius Annaeus Seneca himself. Cordoba’s greatest son much occupied my head at this time. He was less crazy than Petronius, less playful, long-winded but more useful. Thomas More was one of many who prized the practical advice of Nero’s speechwriter and tutor, the playwright paid to put the best words forward at all times, to make his master as little hated as was possible. Ronnie’s speeches (let me name him as she did, ‘dear Ronnie’) were invaluable to Margaret Thatcher.

If these memories seem a little detached, that would be a very fair comment about me at the end of the 1970s. I much preferred the first centuries BC and AD to all other centuries particularly my own. Ronnie was right. There was much of the now that I did not know and had not seen. I afterwards became more a part of modernity but am slipping back again now.

By 1979, when Margaret Thatcher and I coincided after The Undertaking, I had tried various jobs, from BBC Radio in Leeds to advertising chocolate. I spent as much of my time as possible in front of a stage. I wrote theatre reviews for a magazine that no longer exists. I was twenty-eight years old. I had a new job at the Sunday Times and a part-time role, at £5 per script, reading plays for the National Theatre, newly opened on the South Bank of the Thames amid a pious promise that every text submitted by the public would be considered for glory.

Alongside the politics and the Latin, spilling out today from a soon-to-be-sealed box on my floor, are some of the play-titles from that time, invoice letters with NT in red capitals, Stations Upon The Pilgrimage Of The Werewolf (by Dai Vaughan), On The Knowledge (by Dai Vaughan), Krieg Ist Ein Traum or A Waltz (by someone who may not be Dai Vaughan but whose name has faded over the years).

Each £5 fee is accompanied by a cross note from a woman in the script department deploring what a waste of effort this all was. Princess Ascending? We think not. The Alternative? If only. Go Down, Mr Pugh? Bete Noire? The Fuhrer Is Coming? Not if he had to read stuff like this.

The Undertaking, a new play by a man better known for acting in the television series, Doctor Who, was one of many I reviewed that year. The Lenin-and-Leopold-like undertaker notes that all investigation is stopped into a ‘national scandal’ when ‘unstoppable procedures’ reveal ‘just who is involved’. If Miss R were a newspaper interviewer looking for cheap points, she could say that I already had the next phase of my life in mind, the search for corruption and cover-up, the things that journalists like to find. But Miss R is not writing for a newspaper.

In the Autumn of 1979 that ‘next phase’ had barely begun. I had just spent eighteen months as a restless young man working lazily in an oil company office and with time to spend on writing short pieces about politics and poking them anonymously through the doors of magazines. Crossing the Thames at night to offices like this one where I am sitting now, waiting to see if an editor might bite on my morsel: that was my weekly thrill.

One of these offerings, on some now incomprehensible controversy of the day, had attracted enough attention to get me offers of full-time jobs in journalism. That was how I joined the Sunday Times as a business and political reporter – at the much-improved salary of £7,500 per year.

A printed contract for my first ‘proper job’, carbon-copied in the manner of the time, is on my floor too, beside my ‘scoop’ about Industrial Democracy in the now defunct New Society. Miss R can see both if she wants to. She can check the numbers from before the time that she was born. I can never remember numbers. This is maybe the only joy of moving, the easy reminders of lost details.

So August 27th, the date clear from a clipping here from Plays and Players, was, in fact, one of the last days of my old life. I was at a theatre in faraway Greenwich, with a brief to see a two-act play that began, as I recall it, with a European symphony and ended with a woman famed most for her part in a vermouth commercial being raped by a skeleton. And that was certainly the night that I first saw Margaret Thatcher. I am sure that she did not see me.

![]()

8.4.14

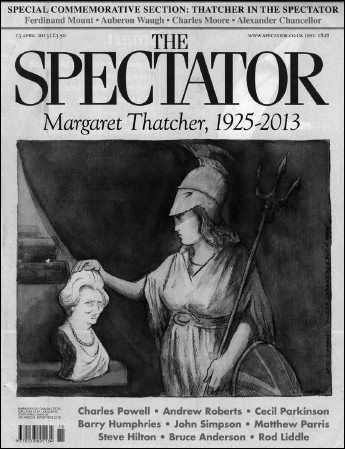

On this day last year Lady Thatcher died, aged eighty seven, mildly demented, demeaned, in my view and the views of many, by a title that she did not need and need never have taken. I was in hospital at the time. I hardly noticed that death elsewhere. I did not mourn it.

To judge from the flickering grey images on a high-mounted TV the only thing she had ever done in her three transforming terms as Prime Minister was to take back the Falkland Islands in 1982, the year before her second election victory. There were sailors and soldiers everywhere. To hear the news commentaries she might have been being buried with two crossed batons and a wreath of oak leaves. The funeral would have perfectly suited any Field Marshal anywhere. Argentine or British? It would hardly have made a difference.

So instead I am mourning her here now. Most of those with whom I watched her rise and fall are dead too. Miss R’s four chosen men are all gone. So much that reminds me of them is also about to die, directly in front of my eyes, brick by brick, pane by broken pane, a demolition in which more than matter will descend as dust. Not only are the newspapers now leaving Thomas More Square, but the original ‘Wapping’ that is down below me, the one that only the oldest among us knew, is about to be destroyed. And only a few now will mourn that.

The first time that I saw this Wapping was a month before the street battles of 1986, the year before her third election victory, the days of the greatest secrecy I had ever known, days of enforced silence, the stress of everyone. Charles Douglas-Home, the Editor at the melon-balls lunch, was dead. His successor, Charles Wilson, and a driver called Jo brought me down here in a black-windowed car.

The distance was short. At 1 pm I was at the Gray’s Inn Road offices where my job as a Thatcher-watcher had begun. At 1.15 pm I was shown the future and how it would work, computers without print-workers, print machinery with ten men instead of a hundred, the ramps down which lorries played the part of trains, the gatehouse and walls that would protect us until the enemies of change became used to it.

As a man of new hopes for employment I hoped very much that the future was going to work. My first job after the security of Shell UK had lasted only three months. By January 1979 the Sunday Times and its daily sister were ‘shut down’ in one of the many so-called, sweetly called, ‘industrial disputes’ that propelled Mrs Thatcher to power. It had felt quite possible that they would never open up again.

The papers did reopen and struggled on. The new Conservative Prime Minister promised to cure the British sickness without killing the British patient but the treatment was slow. All power to her – or so it seemed to me, and to most of those who managed the newspapers, including the new editor of The Times in 1986, a Scot like his predecessor but less ideological, an ex-marine, a giver and demander of fierce loyalty, irascible and well suited to an almost military campaign.

All battles between trade unions and employers were political then. Strikes were the subject about which political writers wrote. There are hundreds of newspaper cuttings on this floor to remind me, once pasted in order, now yellow and free.

Almost no one keeps cuttings any more. They have websites. The only record is electronic. But in the 1980s we all had ‘cuttings books’, marbled ledgers of our productivity, stiff pages which the editor could count if our value for money was in doubt. The requirement for stories was not high. Newspapers were small and staffs were huge until the ‘Wapping Revolution’. But even in the early 1980s it was useful to have one’s name in the paper from time to time. The order to visit the managing editor and bring your cuttings book was a headmasterly summons demanding attention and sticky paste.

I have never thrown mine away. They are all here now, filled with gaps but still a record of what I used to do. For several weeks in 1980, from Doncaster to Dagenham, I seem to have done nothing but count the days ‘lost to strike action’. The results cover four full pages, a blurring record from a time when newspaper offices too were just small parts of factories and not, like Thomas More Square, suitable for a City bank.

In another week I interviewed ‘the man who puts the words in Mrs Thatcher’s mouth’. That was how I first met Ronald Millar, not yet Ronnie or Sir Ronald, playwright, speechwriter, soon to be my closest friend among the courtiers on Miss R’s list.

Miss R is right to want to understand the role of these lesser men. Yes, all Mrs Thatcher’s courtiers were men. Each gave her a different form of comfort. Thus they were means of seeing her when other means were closed, their minds flexible when hers had to be fixed. Sometimes eccentric, always expendable, they gave as well as took. When I was first writing about her I needed these exchanges. I saw her in person, ‘in the flesh’, hardly at all.

That very first ‘editorial lunch’, after I had moved from the Sunday Times to The Times in 1981, was a rarity. That was why the level of sycophancy was so high. There was less close association between Prime Minister and journalists than became common later. A lunch was an ‘event’. For her it was almost a stage performance. In one of the paper piles on the floor there is a detailed note of it that I can use if Miss R wants a detailed answer. I am beginning to hope that she does.

There will be records here (and elsewhere?) of when the Senecans met and what we learnt, how we laughed together about the knifing of friends, of enemies too, how we rejoiced in falls and failures. We loved undue expectations and unjust deserts. We loved the whole business of newspapers, a love that remains.

We had so many rows – beginning with why the Argentines were able to invade the Falklands, arguments less reprised at her death than the Goose Green glory of the Islands’ recapture. We had harsh words about the sinking of an enemy ship called the Belgrano, about the ‘disgraceful’ Times role in the affair of Cecil Parkinson’s mistress, the transmigration of footballer’s souls, and the struggles about whether a helicopter company called Westland should be sold to Europeans whom no one had ever heard of or to Americans who were equally obscure. But little anger lasted beyond a day, the unit of time that on a newspaper is everything.

It was during that so-called ‘Westland crisis’ (everyone knew the phrase in 1986) that The Times and its sisters moved down below to the place that became ‘Fortress Wapping’ or simply ‘Wapping’, taking the name of a whole riverside address to itself, to a new print plant of brick and steel where no member of a print union would ever tread. It was a brutal process of change, all of it happening within the view from this window. There was violence, there was a death. The roads shook with the rage of lorry-drivers and those attempting to stop them. The result was to be a new newspaper era.

Wapping, like Westland, was both an industrial dispute within a single company and a conflict of visions, Europeans or Americans, Thatcher or the paternalism that had predominated before. My notebooks of the time are mostly of minutiae, some of it hard now even to understand, reports of acts by unremembered names. But some names remain, some acts by Miss R’s chosen names. I will answer her as best I can. I saw some things here that others did not see. I have stayed much longer than most. I have looked at events through more lenses. Perhaps I can claim some sense of proportion – or, if merely another distortion, at least one that is different.

When I first drove through that gatehouse down below, seven years after that theatrical night out in Greenwich, six years after the ‘shut-down’ and sullen reopening, my job was still to write about the Thatcher court, Margaret, her enemies and friends. I acquired other positions too, writing rhetoric and opinions, editing the rhetoric and opinions of others. In 1992, after John Major won his only election as Prime Minister, I became Editor of The Times with new ties to Miss R’s four men, ties that lasted till they died.

I dealt with some mad men of my time. Many are not on Miss R’s list but easily might have been. David was neither the maddest nor the most important but he fascinated me from the start. He was also the first to identify that I might be as useful to him as he was to me. Classics is a good training for understanding a court, a constant reminder of madness and mutual dependency. It was useful that I always kept some part of my mind in antiquity just as I had done as an Essex boy, as an adolescent at Oxford, and as and whenever I could. Latin became a shared language at Wapping for a while.

Today, as I’m getting ready to leave here, not quite thirty years on, I am lucky. I can be an open classicist again. I have ‘come out’, as it were. Much of my ‘day job‘ at the TLS is to read and write about Greeks and Romans and those, like the Thomas More of our square, who brought classical languages to England.

For more than a decade I have been back in the books where I began. When I wrote in 2010 about my near-death from a rare form of cancer it was in a book about the Spartacus slave war. When I wrote in 2012 about the fatal cancer of my oldest Essex friend it was in a book about Cleopatra. The approach of any death intensifies memory.

Every day I edit the TLS. I concentrate on the classics as much as I can. I spend time with Romans, politicians, philosophers and poets, with the men and women who study them, with those who are sometimes like them now. It has been an easy adjustment of emphasis, hardly more than that. Wondering what to say to Miss R at first made remembering harder, her restlessness, her petulance, what seems to be a peculiar sense of entitlement. I am now beginning to remember much more. In its final weeks this place is becoming more of a spur than any person alone could be.

Soon our great brick ‘plant’, the dull red squatter outside my sixth-floor Wapping window, will itself be dead, the one over which so many fought so hard in the Thatcher high days. Even when the fighting was over, Fortress Wapping remained its name. It is soon about to be razed and replaced by flats that will have other gentler names, or so the developers hope.

I can tell the kind of people that the new owners want, the men and women on the posters, men with laptops, women holding hands with women holding phones, the young with £2-5 million to spend, not, I suspect, Miss R. I am beginning to miss that plant already, unlovely and unloved as it always was when it was alive. Its walls have not fallen yet but the time must be close.

There are the ghosts here not just of the people who came, who worked here, who lobbied and plotted, but also of the players who brought us here, who set the scene. Margaret Thatcher never came to Wapping herself but she so often seemed to be here. She seems to be here now. No. I must not get beyond what I saw.

Here on the emptying shelves I have a note of most of what she and I ever talked about, most of the times that we met, fewer quotes of her exact words than a historian would like, more usually the gist of what she said. I have notes of her rages and notes, as long as I can find them, about the men who tried to calm her – with flattery, gossip and theatre trips.

I must not make assumptions. I need to prepare myself. Miss R has already asked questions about the towers in the landscape, old Wapping blocks of flats built to house the men and women bombed out of the slums by Hitler. She seemed disappointed that I knew so little, the names of a few pubs on the ground, nothing in the sky apart from some heavy Hawksmoor churches, even those names being a bit blurred, a George in the East and a St Anne’s being less distinct than I would have liked.

Her displeasure came not, I think, because she cared about churches or concrete but because I might have been damaging myself as a witness to what she does care about. Mine are more bookish times now. Miss R is not concerned about the controversies of my new life. She cares about what happened in recent history, always the most forgotten kind.

![]()

10.4.14

When Miss R arrives today she is most pleased by her own notebook, smug I would say but don’t. This is not a new electronic device. She holds it so that I can see the printed name, with a stamp from Foyles bookshop, SENECA, its cover page orange and the next page lemon, both colours faintly silvered. The printed letters of the name are blue-black, the colour of her nail varnish. SENECA belongs to one of the bookseller’s SCHOOLS OF THOUGHT.

I make no comment. I don’t know whether she is prodding or mocking. Eventually she pushes it across my desk. There are few of her own words in it yet. Most of the pages are still blank. But the publisher’s words are succinct: ‘Seneca (c. 4BC–65AD) wanted to keep his integrity and flourish in treacherous times. He directed political reforms while trying to keep Nero, the most volatile of emperors, under control’.

‘Is that fair?’, she asks.

‘Yes’, I reply, ‘fair as far as it goes.’ I cannot keep back that always irritating ‘as far as it goes’, favourite of those who dislike issues of long study reduced to a single word.

‘I want to talk about your Senecans. Were they “trying to control”?’

‘Not in every case. David preferred Margaret Thatcher when she was out of control. Seneca was the first political speechwriter. That was his main attraction to Ronnie. A writer is often in a position to control the ruler for whom he writes.’

She raises a pale plucked eyebrow. ‘Seneca is also praised in the notebook for his insight that “immediate pleasure is an unreliable guide to living a good life”. True?’

Seneca and Socrates

‘That is certainly what Seneca said’, I reply. ‘He used to write it often and in many ways. Margaret Thatcher instinctively agreed with him. She was a Stoic in that and many respects. She thought that too many of her predecessors had indulged the public love of immediate pleasure. The Senecans, of course, like all good courtiers, liked to find respectable support for every view that she held.’

Miss R continues to read aloud. She speaks at a higher pitch and volume than our office space requires, as though these were slogans to be etched on the glass walls.

‘“Seneca was interested in making money but knew that it couldn’t guarantee security. He hardened himself against the natural fear of losing what he had by regular bouts of voluntary frugal living”. Is that true too?’

‘That is how Seneca wanted people in the future to see him. But the three points are not quite the same.’

‘So first: making money?’

‘By owning silver mines and lending at high interest. Yes, he did like to make money although taking money was easier and left him more time to think.’

‘And natural fear?’

‘The natural was good. Anything that he deemed natural was the virtuous thing.’

‘Voluntary frugal living?’

‘His chest heaved every day of his life. His throat was a cave of coughs. His stomach ached at the slightest provocation. He made wine on an industrial scale but drank in moderation – or that is what he claimed. He enjoyed sex and cold baths whenever and with whomever he liked. Does that count as frugality or not?’

Miss R frowns. She closes the book. Her purchase from Foyles may not explain everything about Seneca. It misses the tough, practical thinking about politics, the contrariness, the appeal to first principles that were so prized at Margaret Thatcher’s court and so missed after she had gone. It misses the mechanics of exchanging favours, the problems of giving benefits to all when all will not deserve them. It misses much that was to become important to all of the four men on her list.

The publisher of SCHOOLS OF THOUGHT does, however, explain one big thing about Seneca. The teacher’s son from Cordoba wanted to help. He wanted to be a help to himself. Miss R reads aloud in her glass-etching voice again.

‘“He encourages us to be tough with ourselves so that we can cope with life and make the most of bad circumstances. Dampening hope or preparing for adversity liberates your energies”.’

I have nothing to say about the liberation of energies. But this self-help Seneca from Foyles is, quite correctly, a man who intended to do good.

‘Virtuous intention was important to him. He aimed high while recognising that he might never match the best of men.’

‘Seneca did not become Emperor of Rome himself’, I add, ‘despite being the candidate of virtue in some men’s minds.

He thought anger was the greatest evil. A man had to stay cold and calm, a ruler most cold and calm of all.’

‘Passion was not a part of sound reasoning but its most pernicious enemy. He never had the chance to test his thoughts on the biggest political stage. A hundred years later his successor Stoic in your plastic packet, Marcus Aurelius, did succeed, the so-called “last of the Good Emperors”.’

She takes her notebook back, complains about the confusion in my office and leaves the room. Five minutes later I see her walking out the back way eastwards towards the plant that is about to fall, down the road beside the rum store to the end. I watch her until she turns left towards the pale, purple columns of The Old Rose, the pub, long closed now, where the Senecans used once to study Stoicism and learn their verbs.

![]()

18.4.14

Cranes are arriving like dinosaurs for breakfast in a swamp, a rain-swept convention of diggers and dumper trucks. This is a scene with few people and much machinery, just like the world that is departing. The Wapping print-production lines, so dramatic when I saw them first, were bright blue. The colour for demolition is yellow.

When Miss R arrives she has no raincoat. Perhaps she has a friend here who drives her into the basement where the service lift begins, where security is not so strict. She sweeps back my half-formed question and joins me at the window. We watch the show.

Does she enjoy this sort of meeting? It is hard yet to say. Doubtless she is talking to dozens of people. I hardly look fit for a big part in her history. She writes down some of what I say, but not enthusiastically, merely with a dogged purpose, like a student seeing an examination answer through the verbiage of a lecture. Sometimes I must have something she needs.

I want to help her if I can. I am not sure why. Because a few facts ought not to be forgotten? Because I am flattered to be asked?

Maybe I would be more persuasive if I were better dressed, wearing one of my old blue suits chalked with a thin stripe, made by the only tailor I have ever had, a maker of fox-hunting kit in York whom I met by chance and kept by habit.

From the evidence today of the packed box on my floor marked ‘Peter’s photographs’, those suits did not fit my body well. The jackets were double-breasted, at least double. The trousers were equally full, held by yellow braces I cannot imagine wearing now. But they were the uniform for being heard then.

Those suits long ago went to moths and Oxfam. When I saw Miss R last week I was wearing the same grey-pink cotton jacket that I am wearing today, bought a decade ago in Rome when I was a thin man, and some pumice-grey trousers, creased from their time in the back of my desk drawer beside shoe polish and sugar cubes.

The instruction from on high in the company is that all desks must be emptied within three months. In September I am going to the Roman city in Spain where Lucius Annaeus Seneca was born. Before I go to Cordoba, everything of mine must be out of here. I need to take special care of the contents of the case closest to me, David Hart’s Renaissance erotica (photocopies only), his Sons and Lovers (David Lawrence was his favourite alias), Ronnie Millar’s Roman tragedies (all by Seneca), three Booker Prize-winners, one of them a bribe from Woodrow Wyatt, and various black novels by Beryl Bainbridge, who never won the Booker Prize but was all the more loved for that by Woodrow.

Beneath these are various relics of my own in Latin, Greek and what the memoir-writing politicians of my own time claim is English. Every day this Spring is a removals day although nothing yet has been removed. I have enjoyed this TLS office, the last of dozens where I have made newspapers, my very last it seems, before the absolute new era of ‘open-plan’. My past is filed here in a solid form.

As well as paper of every age and colour there is a small brass grinding pot which my mother used to call ‘the middle thing’ when I was a Chelmsford child on our armament-makers’ estate, a blue school cap with my senior school’s motto, Incipe, an injunction to Begin!, an Oxford tie from a time no one wore a tie, two cracked pillboxes, one showing a whiskered Victorian with a copy of The Times, the other a Roman empress spreading her legs on a throne. Miss R strokes the school cap and ignores Messalina. There are files of letters, brown ink pages tied with rusting wire, a thousand books at least, novels, histories, memoirs of every kind including mine.

Miss R today is less like a historian’s assistant, more like a mother in a teenager’s bedroom, intolerant of the filing on the floor. She trips. She swears. There is no place to put her mid-heeled shoes, not white this time but two-tone blue with a bow, right foot and left foot eventually secure but further apart than she would have liked, small stacks of Latin staring up in between. She is coming to resent the boxes that are waiting to be taped and moved, all twelve of them. I know the number because I watch her write it down, XII, as though denoting a Roman poem or a Pope.

She stands rather than risk the seat of books. She turns down the offer of a chair from the main office outside. She leans against a cabinet. She slides on a slippery plastic file. Only while she settles do I properly note what she is wearing, the blue skirt ruffled shorter over her left thigh than the right, the white plastic bangle on her wrist. Her shoulders are wider than would be normally seen today in Thomas More Square, power-dressed as we used to say in the 80s, dressed in period for her research as I am tempted to say now.

It seems more important today for her to be near the window than to be comfortable. Together we admire the cranes. I ask her again if she wants a chair. There is room for another behind my desk if I disturb a small part of my soon-to-be travelling museum. But the remains from my fifty years as student, reporter and editor do not have to defend their ground. Instead she takes two halting steps and scans again the line of sky, the cloud-clinging concrete blocks, the slate and marble churches, the bricks of what were once the London Docks, the red-brick cube of the plant and the black-brick cylinder beside it for The Times.

‘You must be sorry to be leaving here’, she says, looking again at the boxes as though to check once more that she has counted them correctly. ‘We can both see so much of what we need to talk about.’